THE SHADOW OF THE DALAI LAMA: SEXUALITY, MAGIC AND POLITICS IN TIBETAN BUDDHISM; THE DALAI LAMA (AVALOKITESVARA) AND THE DEMONESS (SRINMO), Part 1

History as understood in the Kalachakra Tantra is apocalyptic salvational history, it is — as we have said — an alchemic experiment aimed at producing an ADI BUDDHA. The protagonists in this drama are no mere mortals but gods. History and myth thus form a union. If we take the philosophy of Vajrayana literally then all the events of the tantric performance ought to be able to be found again in the history of Tibet. The latter should therefore be interpreted as the expression of a sexual dynamic. Before we ourselves begin to search for symbolic connections and mythic fields behind the practical political facts of Tibetan history, we should ask ourselves whether the Tibetans have not of their own accord conducted such a sex specific and sexual magic interpretation of their historical experiences.

We know that the rules of the game demand two principal actors in every tantric performance, a man and a woman, or, respectively, a god and a goddess. In any case the piece is divided into three acts:

1. The sexual magic union of god and goddess

2. The subsequent “tantric female sacrifice”

3. The production of the cosmic androgyne (ADI BUDDHA)

Let us turn our attention, then, to the individual scenes through which this cosmic theater unfolds on the “Roof of the World”. Here, the country’s myths of origin are of decisive significance, as they provide the archetypal framework from which, in an ancient conception of history, all later events may be derived.

The bondage of the earth goddess Srinmo and the history of the origin of Tibet:

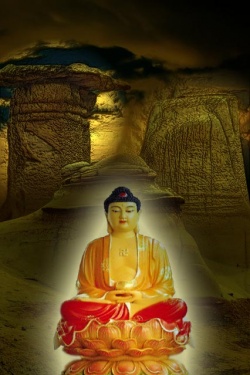

The Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara is considered the progenitor of the Tibetans, he thus determines events from the very beginning. In the period before there were humans on earth, the Buddha being was embodied in a monkey and passed the time in deep meditation on the “Roof of the World”. There, as if from nowhere, a rock demoness by the name of Srinmo appeared. The hideous figure was a descendent of the Srin clan, a bloodthirsty community of nature goddesses. “Spurred on by horniness” — as one text puts it — she too assumed the form of a (female) monkey and tried over seven days to seduce Avalokiteshvara. But the divine Bodhisattva monkey withstood all temptations and remained untouched and chaste. As he continued to refuse on the eighth day, Srinmo threatened him with the following words: “King of the monkeys, listen to me and what I am thinking. Through the power of love, I very much love you. Through this power of love I woo you, and confess: If you will not be my spouse, I shall become the rock demon’s companion. If countless young rock demons then arise, every morning they will take thousands upon thousands of lives. The region of the Land of Snows itself will take on the nature of the rock demons. All other forms of life will then be consumed by the rock demons. If I myself then die as a consequence of my deed, these living beings will be plunged into hell. Think of me then, and have pity” (Hermanns, 1956, p. 32). With this she hit the bullseye. “Sexual intercourse out of compassion and for the benefit of all suffering beings” was — as we already know — a widespread “ethical” practice in Mahayana Buddhism. Despite this precept, the monkey first turned to his emanation father, Amitabha, and asked him for advice. The “god of light from the West” answered him with wise foresight: “Take the rock demoness as your consort. Your children and grandchildren will multiply. When they have finally become humans, they will be a support to the teaching” (Hermanns, 1956, p. 32).

Nevertheless, this Buddhist evolutionary account, reminiscent of Charles Darwin, did not just arise from the compassionate gesture of a divine monkey; rather, it also contains a widely spread, elitist value judgment by the clergy, which lets the Tibetans and their country be depicted as uncivilized, underdeveloped and animal-like, at least as far as the negative influence of their primordial mother is concerned. “From their father they are hardworking, kind, and attracted to religious activity; from their mother they are quick-tempered, passionate, prone to jealousy and fond of play and meat”, an old text says of the inhabitants of the Land of Snows (Samuel, 1993, p. 222).

Two forces thus stand opposed to one another, right from the Tibetan genesis: the disciplined, restrained, culturally creative, spiritual world of the monks in the form of Avalokiteshvara and the wild, destructive energy of the feminine in the figure of Srinmo.

In a further myth, non-Buddhist Tibet itself appears as the embodiment of Srinmo (Janet Gyatso, 1989, p. 44). The local demoness is said to have resisted the introduction of the true teaching by the Buddhist missionaries from India with all means at her disposal, with weaponry and with magic, until she was ultimately defeated by the great king of law, Songtsen Gampo (617-650), an incarnation of Avalokiteshvara (and thus of the current Dalai Lama). “The lake in the Milk plane,” writes the Tibet researcher Rolf A. Stein, “where the first Buddhist king built his temple (the Jokhang), represented the heart of the demoness, who lay upon her back. The demoness is Tibet itself, which must first be tamed before she can be inhabited and civilized. Her body still covers the full extent of Tibet in the period of its greatest military expansion (eighth to ninth century C.E.). Her spread-eagled limbs reached to the limits of Tibetan settlement ... In order to keep the limbs of the defeated demoness under control, twelve nails of immobility were hammered into her” (Stein, 1993, p.34). A Buddhist temple was raised at the location of each of these twelve nailings.

Mysterious stories circulate among the Tibetans which tell of a lake of blood under the Jokhang, which is supposed to consist of Srinmo’s heart blood. Anyone who lays his ear to the ground in the cathedral, the sacred center of the Land of Snows, can still — many claim — hear her faint heartbeat. A comparison of this unfortunate female fate with the subjugation of the Greek dragon, Python, at Delphi immediately suggests itself. Apollo, the god of light (Avalokiteshvara), let the earth-monster, Python (Srinmo), live once he had defeated it so that it would prophesy for him, and built over the mistreated body at Delphi the most famous oracle temple in Greece.

"The outer darkness is a great dragon, whose tail is in his mouth, outside the whole world and surrounding the whole world. And there are many regions of chastisement within it. There are twelve mighty chastisement-dungeons and a ruler is in every dungeon and the face of the rulers is different one from another. -- Pistis Sophia: A Gnostic Miscellany, Translated by G.R.S. Mead

The earth demoness is nailed down with phurbas. These are ritual daggers with a three-sided blade and a vajra handle. We know these already from the Kalachakra ritual, where they are likewise employed to fixate the earth spirits and the earth mother. The authors who have examined the symbolic significance of the magic weapon are unanimous in their assessment of the aggressive phallic symbolism of the phurba.

In their view, Srinmo represents an archetypal variant of the Mother Earth figure known from all cultures, whom the Greeks called Gaia (Gaea). As nature and as woman she stands in stark contrast to the purely spiritual world of Tantric Buddhism. The forces of wilderness, which rebel against androcentric civilization, are bundled within her. She forms the feminine shadow world in opposition to the masculine paradise of light of the shining Amitabha and his radiant emanation son, Avalokiteshvara. Srinmo symbolizes the (historical) prima materia, the matrix, the primordial earthly substance which is needed in order to construct a tantric monastic empire, then she provides the gynergy, the feminine élan vitale, with which the Land of Snows pulsates. As the vanquisher of the earth goddess, Avalokiteshvara triumphs in the form of King Songtsen Gampo, that is, the same Bodhisattva who, as a monkey, earlier engendered with Srinmo the Tibetans in myth, and who shall later exercise absolute dominion from the “Roof of the World” as Dalai Lama.

Tibet’s sacred center, the Jokhang (the cathedral of Lhasa), the royal chronicles inform us, thus stands over the pierced heart of a woman, the earth mother Srinmo. This act of nailing down is repeated at the construction of every Lamaist shrine, whether temple or monastery and regardless of where the establishment takes place — in Tibet, India, or the West. Then before the first foundation stone for the new building is laid, the tantric priests occupy the chosen location and execute the ritual piercing of the earth mother with their phurbas. Tibet’s holy geography is thus erected upon the maltreated bodies of mythic women, just as the tantric shrines of India (the shakta pithas) are found on the places where the dismembered body of the goddess Sati fell to earth.

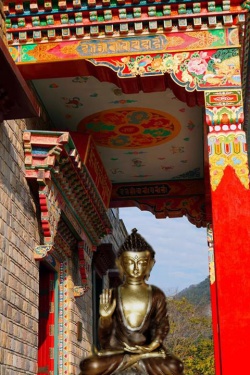

Srinmo with different Tibetan temples upon her body

In contrast to her Babylonian sister, Tiamat, who was cut to pieces by her great-grandchild, Marduk, so that outer space was formed by her limbs, Srinmo remains alive following her subjugation and nailing down. According to the tantric scheme, her gynergy flows as a constant source of life for the Buddhocratic system. She thus vegetates — half dead, half alive — over centuries in the service of the patriarchal clergy. An interpretation of this process according to the criteria of the gaia thesis often discussed in recent years would certainly be most revealing. (We return to this point in our analysis of the ecological program of the Tibetans in exile.) According to this thesis, the mistreated “Mother Earth” (Gaia is the popular name for the Greek earth mother) has been exploited by humanity (and the gods?) for millennia and is bleeding to death. But Srinmo is not just a reservoir of inexhaustible energy. She is also the absolute Other, the foreign, and the great danger which threatens the Buddhocratic state. Srinmo is — as we still have to prove — the mythic “inner enemy” of Tibetan Lamaism, while the external mythic enemy is likewise represented by a woman, the Chinese goddess Guanyin.

Srinmo survived — even if it was under the most horrible circumstances, yet the Tibetans also have a myth of dismemberment which repeats the Babylonian tragedy of Tiamat. Like many peoples they worship the tortoise as a symbol of Mother Earth. A Tibetan myth tells of how in the mists of time the Bodhisattva Manjushri sacrificed such a creature “for the benefit of all beings”. In order to form a solid foundation for the world he fired an arrow off at the tortoise which struck it in the right-hand side. The wounded animal spat fire, its blood poured out, and it passed excrement. It thus multiplied the elements of the new world. Albert Grünwedel presents this myth as evidence for the “tantric female sacrifice” in the Kalachakra ritual: “The tortoise which Manjushri shot through with a long arrow ... [is] just another form of the world woman whose inner organs are depicted by the dasakaro vasi figure [the Power of Ten]" (Grünwedel, 1924, vol. II, p. 92).

The relation of Tibetan Buddhism to the goddess of the earth or of the country (Tibet) is also one of brutal subjugation, an imprisonment, an enslavement, a murder or a dismemberment. Euphemistically, and in ignorance of the tantric scheme of things it could also be interpreted as a civilizing of the wilderness through culture. Yet however the relation is perceived — no meeting, no exchange, no mutual recognition of the two forces takes place. In the depths of Tibet’s history — as we shall show — a brutal battle of the sexes is played out.

Why women can’t climb the pure crystal mountain:

Even the landscape is sexualized in Tibetan folk beliefs (this too squares with the ideas of Tantrism). In mountain lakes, the water of which has taken on a red color (probably because of mercury), the lamas see the menstrual blood of the goddess Vajravarahi. In rivers, lakes, and springs dwell the Lu, who resemble our nixies. They are hostile towards we humans, yet they were nonetheless preferred as spouses by the kings of the highlands in ancient times and brought their magic abilities with them in the marriage. We learn from the Fifth Dalai Lama that they leave no corpse behind when they die.

The myths have also divided the massive snow capped peaks along sexual lines. It was hence not uncommon for particular mountains to marry and the descendants of such alliances are supposed to have grounded powerful royal houses. One of the mountain goddesses is world famous, because it rises above the other peaks of the planet as the highest mountain of all. We know her under the name of Mount Everest, the Himalayan peoples, however, pray to her as the “Mother of the Earth”, the “White Heavens Goddess”, the “White Glacier Lady”, the “Goddess of the Winds”, the “Lady of Long Life”, the “Elephant Goddess”.

In his study with the descriptive title of Why can’t women climb pure crystal mountain?, the Tibet researcher Toni Huber describes an interesting mythic case where a mountain goddess was deprived of her power by a tantric Siddha and since then the location of her former rule may no longer be visited by women. The case concerns the Tsari, a mountain which was the seat of a powerful female deity in pre-Buddhist times. She was defeated by a yogi in the twelfth century. The brutal battle between her and the vajra master displays clear traits of a tantric performance. As the yogi entered the region under her control, the goddess let a series of vaginas appear by magical manipulation so as to seduce her challenger, yet the latter succeeded in warding off the magic through a brutal act of subjugation. As she then, lying on the ground, showed herself willing to sleep with her conqueror, she was at first rejected on the grounds that she was of the female sex (!). But after a while the yogi accepted her as a wisdom consort and took away all her magic powers once they had united sexually (Huber, 1994, p. 352).

From this point in time on, Tsari, which was among the most holy mountains of the highlands, became taboo for women, both for Buddhist nuns and for laity. This ban has remained in force until modern times. Groups of pilgrims who visited the mountain in the eighties sent their women back in advance. Toni Huber questioned several lamas about the significance of this misogynist custom. The majority of answers made reference to the “purity of the location” which in the view of the monks formed a geographic mandala: “Because it is such a pure abode, .... women are not allowed. ... The only reason is that women are of inferior birth and impure. There are many powerful mandalas on the mountain that are divine and pure, and women are polluting” (Huber, 1994, p. 356).

But there was also another justification for the exclusion of the female pilgrims which likewise shows how and with what presumption the androcentric power elite of the land seize possession of the formerly feminine geography: “The reason why women can't go up there is that at Tsari are lots of small, self-produced manifestations of the Buddha genitals made of stone. If you look at them they just appear ordinary, but they are actually miraculous phalluses of the Buddha, so if women go there these miracles would become spoiled by their presence, and the women would get many problems also. They would get sick and perhaps die prematurely. It is generally harmful for their health so that is why they stopped women going to the holy place in the past, for their own benefit. The problem is that women are low and dirty, thus they are too impure to go there” (Huber, 1994, p. 357). It is no wonder that in feminist circles the future climbing of Tsari by a woman and its “re-conquest” has become a symbol for female resistance against patriarchal Lamaism.

Matriarchy in the Land of Snows?:

Siegbert Hummel sees remnants of a long lost maternal cult in the Tibetan female mountain deities and their attributes. These could have already reached India and the Tibetan plateau from Mediterranean regions in the late stone age (from 4000 B.C.E.). It is a matter of one of the two contrary cultural currents, which may have embedded themselves deeply in the Tibetan popular psyche thousands of years ago: “The first is lunar in character and could be connected with the Tibetan megalithic. ... Its world view is triadic, exhibits chthonic, demonic and phallicist tendencies, snake and tree cults, as well as the worship of maternal deities ... The other component is markedly solar, dualist and heaven-related, primarily nomadic. Shamanist elements, probably from an earlier solar, hunting basis, are numerous” (Hummel, 1954, p. 128).

In that he nominates the sexual discord which has kept the civilizations of the Land of Snows in suspense since the earliest times, Hummel speaks here with the vocabulary of Tantrism, probably without knowing it. In his view then, the two heavenly orbs of moon and sun already stood opposed as two polar, culture-shaping forces in pre-Buddhist Tibet. Following the solar Bon cult Tantric Buddhism has taken over the sunly role since the eighth century. In contrast, the moon cults have been — the myth of the nailing down of Srinmo teaches us — overthrown by the sun warriors.

According to Hummel the lunar and solar cultural currents are graphically demonstrated in the very popular garuda motif in Tibetan art. The garuda is a mythical sun-bird. Not infrequently it holds in its beak a snake, which must be assigned to the lunar, matriarchal world. There was thus a fundamental clash between the two cultures: “Since the garuda is thereby understood as an enemy of the snakes, it seems natural to suspect that where the snake-killing garuda arose, the lunar and solar cultures encountered and opposed one another as enemies” Hummel writes (Hummel, 1954, p. 101).

There are in fact numerous historically demonstrable matriarchal elements in the old Tibetan culture. In this connection there are the still unexplained and mysterious stone circles which have been brought into connection with matriarchal cults and were already discovered by Sven Hedin on his research trips. In contrast, numerous prehistoric shrines found in caves offer us less ambiguous information. It has been clearly proven that female deities were worshipped at these chthonic sites. In this century such caves were still considered as birth channels and a visit to them was seen as an initiation and hence as a rebirth (Stein, 1988, pp. 2-4).

A further secret concerns the mythic female kingdoms which are supposed to have existed in Tibet — one in the West, another in the East, and the third in the North of the Land of Snows. The in part detailed reports about these stem from Chinese sources and may be traced back to the seventh century C.E. We learn that these realms, depicted as being very powerful, were ruled by queens who had command over a tribal council of women (Chayet, 1993, p. 51). When they died several members of court voluntarily joined the female rulers in death. The female nobles had male servants, and women were the head of the family. A child inherited its mother’s name.

On one of his first expeditions to Tibet, Ernst Schäfer encountered a matriarchal tribe who distinguished themselves through their cruelty. In his book, Unter Räubern in Tibet [Among Robbers in Tibet), he reports: “As we learn in Dju-Gompa, primitive matriarchy is still practiced by the wild Ngoloks. A great queen, Adjung de Jogo by name, reigns autocratically over the six main tribes that are governed by princes. As the reincarnation of a heavenly being she enjoys divine honors and at the same time is the spouse of all her tribal princes on earth. She rules with a strong hand, is pretty and clever, possesses a bodyguard of seven thousand warriors, and handles a gun like a man. Once a year Adjung de Jogo proceeds up the God-mountain with her seven thousand men in a grand procession in order to meditate in the glacial isolation before she returns to the black tents of her mobile residence.

It is not just about the intrepid courage of the Ngoloks but also their cruelty that people tell the most terrible stories. Of all the Tibetan tribes they are supposed to have figured out the most ingenious ways of despatching their victims off to join their ancestors. Chopping off hands and splitting skulls are minor things; they can be left to the others! But sewing (people) up in fresh yak skins and letting them roast in the sun — disemboweling while alive, or launching the entrails skywards on bent rods, these are the methods that are loved in Ngolokland.

At nearly all times of the year, but especially in early fall when the marshes are dried out and the animals are best nourished, the Ngoloks undertake their large-scale plundering raids to as far as Barum-Tsaidam in the north, Sungpan in the south, and Dju-Gompa in the West. Even for Chinese merchants they are the epitome of all the terrible things that are said of the “Western barbarian country” in the Middle Kingdom. (Schäfer, 1952, pp. 164-165)

In the nineteen fifties, to the south of Bhutan a matriarchally organized tribe by the name of “Garo” still existed, the members of which were convinced that they had emigrated from a province in Tibet in prehistoric times (Bertrand, 1957, p. 41). We may also recall that in the Shambhala travel books of the Third Panchen Lama there is talk of regions in which only women live.

It would certainly be somewhat hasty to conclude the existence of a matriarchy across the whole Himalayas solely on the basis of the material at hand. But at any rate, the male imagination has for centuries painted the inaccessible highlands as a region under the control of female tribes and their queens.

The western imagination:

As early as the thirteenth century the myth of the Tibetan female kingdoms had reached Europe. Speculations about this have had a hold upon western travelers up until the present day. Likewise noteworthy is the frequent allegorical connection of Tibet to something enigmatically feminine, that is, a western imagining which is congruent with the traditional Tibetan conception. Since the nineteenth century European researchers, mountain climbers, and followers of the esoteric have enthused about the Land of Snows as if it were a woman who ought to be conquered, whose veil should be lifted, and into whose secrets one wished to “penetrate”. The Tibet researcher, Peter Bishop, has devoted a detailed study to this occidental fantasy (Bishop, 1993, p. 36).

Probably the most absurd depiction of a western encounter with the “Great Mother Tibet” can be found in the travel report of the Englishman, Harrison Forman, from the nineteen thirties. To offer the reader some amusement, but above all to show how strongly the culture of the Land of Snows can over-stimulate the masculine fantasy of a westerner, we would like to present one of Forman’s lively recounted experiences in detail.

The Briton had heard of the Abbess Alakh Gong Rri Tsang (Krisang), a living “female Buddha” who aroused his curiosity immensely. He visited her convent and was given a most friendly reception. During a tour he asked about a mysterious grotto, the entrance to which could be seen on a mountainside. The Abbess gave him a sharp look and announced she was prepared to show him the “shrine”. In that moment Forman felt a painful bout of nausea, but was nonetheless prepared to follow. Thus, after a difficult climb, they both — he and the Abbess — reached the grotto. Alakh Gong Krisang lit two torches and they entered the cave. They were met by a thick darkness, a musty smell, and dancing shadows. Squeaking bats fluttered through the stale air. The ghastly ambience made the Briton nervous and he asked himself, “A thought struck me. Good Lord! Just what was this woman Living Buddha? Reason struggled with emotion. This was Tibet, where millions believed in ever present evil spirits and their capriciousness” (Forman, 1936, p. 179).

Without looking back, and with a firm footstep, the Abbess proceeded further into the grotto. "Do not be afraid, my friend!”, she calmed Forman. They progressed deeper and deeper through passages filled with stalactites and stalagmites. Then they came to a space in the center of which four pyramids of human bones rose up, with a golden statue in the middle of them. The Abbess smiled as if in a “hysterical ecstasy”, writes Forman. Immobile, she stared at the golden sculpture.

Alakh Gong Rri Tsang, the woman Grand Buddha of Drukh Kurr Gomba

And now we should let the author speak for himself: "And as I watched her, my jaw dropped. I stared as she began to disrobe. A shrug of the shoulders and her long toga slipped to the floor. Then she loosened the silken girdle at her waist and let drop the voluminous skirt-like garment. Her other garments followed, one by one, until they formed a red pile at her feet. And I saw, what I am sure no white man ever saw before me, or ever will see again, the nude body of Alakh Gong Rri Tsang, the woman Grand Buddha of Drukh Kurr Gomba. Her body was amazingly voluptuous, and, I suppose, beautiful. Her breasts stood like those of a schoolgirl, firm and round – like hemispheres of pure alabaster. Her figure was magnificent and of sinuously generous proportions. I was minded of the substantial nudes of Michelangelo and his school. And amid the ever-encircling bats she stood there – still gazing ecstatically upward” (Forman, 1936, p. 183). If we examine the photo which Forman took of the Abbess in the convent and in which she is not to be distinguished from a portly male Abbot, one is indeed most amazed at just what is supposed to be hidden beneath the clothes of the Living Buddha.

But there is better to come: "The bats had suddenly settled on her - like vultures to a feast. In a moment she was covered from head to foot. Like lustful vampires they sank their horrible libidinous beaks into her flesh and the blood began to flow from a hundred wounds” (Forman, 1936, pp. 183, 184). Forman turned to stone, but then — even in the most hopeless of situations a gentleman — he came to his senses, and began to shoot madly at the bloodsuckers with his revolver. He emptied more than seven magazines before the Abbess, to his great astonishment asked him with a smile to calm down. With a majestic gesture she reanimated the bats which he had killed. There was not the slightest trace of a wound to be seen on her body any more. "And in that moment”, Forman reports further, "had she been the loveliest woman in all the world [...] Nothing remained of the grisly scene of a few moments before to prove to me that it had ever happened at all, save the nude woman and the solid golden idol with its four guardian pyramids of human bones. Somewhere off in the blackness I could still hear faintly the obscene screaming of the hordes of bats” (Forman, 1936, p. 185). As they left the grotto, Forman commented upon the incident — typically British — with the lapidary words: "It must be the altitude!” (Forman, 1936, p. 186).

As absurd as this story may seem, it nonetheless quite exactly hits the visual world which dominates the tantric milieu, and it in no way exaggerates the often still more fantastic reports which we know from the lives of famous yogis.

Women in former Tibetan society:

How then is the fate of Srinmo expressed in Tibetan society? We would like to present the social role of women in old Tibet in a very condensed manner, without considering events since the Chinese occupation or the situation among the Tibetans in exile here. Their role was very specific and can best be outlined by saying that, precisely because of her inferiority the Tibetan woman enjoyed a certain amount of freedom. Fundamentally women were considered inferior creatures. Appropriately, the Tibetan word for woman can be literally translated as “lowly born”. Man, in contrast, means “being of higher birth” (Herrmann-Pfand, 1992, p. 76). A prayer found widely among the women of Tibet pleads, “may I reject a feminine body and be reborn [in] a male one” (Grunfeld, 1996, p. 19). The birth of a girl brought bad luck, that of a son promised happiness and prosperity.

The institution of marriage itself is definitely not one of the Buddhist virtues – the historical Buddha himself traded married life for the rough life of a pilgrim. To be blessed with children was, because of the curse which rebirth brought with it, something of a burden. Shakyamuni thus fled his father’s palace directly following the birth of his son, Rahula. With unmistakable and decisive words, Padmasambhava also expressed this anti-family sentiment: "When practicing the Dharma of liberation, to be married and lead a family life is like being restrained in tight chains with no freedom. You may wish to flee, but you have been caught in the dungeon of samsara with no escape. You may later regret it, but you have sunk into the mire of emotions, with no getting out. If you have children, they may be lovely but they are the stake that ties you to samsara” (Binder-Schmidt, 1994, p. 131).

According to the dominant teaching, women could not achieve enlightenment, and were thus considered underdeveloped. A reincarnation as a female being was regarded as a punishment. The consequence of all these weaknesses, inabilities and inferiorities was that the patriarchal monastic society paid little attention to the lives of women. They were left, so to speak, to do what they wanted. Family life was also not subject to strict rules. Marriages were solemnized without many formalities and could be dissolved by mutual consent without consulting an official institution. This disinterest of the clergy led, as we said, to a certain independence among the women of Tibet, often exaggerated by sensation-hungry western travelers. Extramarital relationships were common, especially with servants. A wife nevertheless had to remain faithful, otherwise the husband had the right to cut off her nose. Of course such privileges did not exist in the reverse situation.

The much talked about polyandry, discussed with fascination by western ethnologists, was also less of an emancipatory phenomenon than an economical necessity. A wife served two men because this spared the money for a further woman. Naturally, twice the work was expected of her. Male members of the upper strata tended in contrast toward polygyny and maintained several wives. This became quite a status symbol and having more than one wife was consequently forbidden for the lower classes. In the absence of cash, a husband could pay his debts by letting his creditors take his wife. We know of no cases of the reverse.

A liberal attitude towards women on behalf of the clergy arises out of Tantrism. Since the lamas were generally viewed to be higher entities, women and girls never resisted the wishes of the embodied deities. The Austrian, Heinrich Harrer, was amazed at the sexual freedom found in the monasteries. Likewise, the Japanese monk, Kawaguchi Eikai, wondered on his journey through Tibet about "the great beauty possessed by the young consorts of aged abbots” (quoted by Stevens, 1990, p. 80). A proportion of the female tantric partners may have earned a living as prostitutes after they had finished serving as mudras. There were many of these in the towns, and hence a saying arose according to which as many whores filled the streets of Lhasa as dogs.

But there was a married priesthood in Tibet. For members of a monastery the relaxation of the oath of celibacy was nonetheless considered an exception. These married lamas and their women primarily performed “pastoral” work in the villages. As far as we can determine, in such cases the wife was only very rarely the tantric wisdom consort of her husband. In the Sakyapa sect the great abbots were married and had children. A proper dynasty grew up out of their families. We know of precisely these powerful hierarchs that they made use not of their wives but rather of virgin girls (kumaris) for their rites.

The “freedom” of the Tibetan women was null and void as soon as sacred boundaries were crossed — for example the gates of the monastery, which remained closed to them. Only during the great annual festivals were they sometimes invited, but they were never permitted to participate actively in the performances. In the official mystery plays the roles of goddesses or dakinis were exclusively performed by men. Even the poultry which clucked around in the Dalai Lama’s gardens consisted solely of roosters, since hens would have corrupted the holy grounds with their feminine radiation. A woman was never allowed to touch the possessions of a lama.

The Tibetan nuns do admittedly take part in certain rites, but have in all much more circumscribed lives than those of lay women. Did not the historical Buddha himself say that they stood in the way of the development of the teaching, and long hesitate before ordaining women? He was convinced that the “daughters of Mara” would accelerate the downfall of Buddhism, even if they let their heads be shaved. Still today the rules prescribe that a nun owes the lowliest monk the greatest respect, whilst the reverse does not apply in any sense . Rather than being praised for her pious decision to lead a life in a convent, she is abused for being incapable of building up an orderly family life. Despite all these degradations, to which there have been no essential changes up to the present, the nuns have, without concern for life and limb, stood at the head of the emergent protest movement in Tibet since 1987.

The alchemic division of the feminine: The Tibetan goddesses Palden Lhamo and Tara:

In our explanation of Buddhist Tantrism we repeatedly mentioned the division of the feminine into a gloomy, repellant, and aggressive aspect and a bright, attractive, and mild one. The terrifying and cruel dakini is counterpointed by the sweet and blessing-giving “sky walker”. Femininity vacillates between these two extremes (the Madonna and the whore) and can be kept under control because of this inner turmoil. In the same context, we drew attention to parallels to Indian and European alchemy, where the dark part is described as the prima materia and the bright as the feminine elixir (gynergy) yearned for by the adept. Does such a splitting of the feminine also find expression in the mythical history of the Land of Snows?

Palden Lhamo — The Dalai Lama’s protective goddess:

A monumental dark and wrathful mother par excellence is Palden Lhamo, who, like her “sister” Srinmo, was a wild, free matriarch in pre-Buddhist times, but then, brought under control by a vajra master, began to serve the “true doctrine” — but in contrast to Srinmo she does so actively. She is the protective deity of the Dalai Lama, the whole country, and its capital, Lhasa. This grants her an exceptionally high position in the Tibetan pantheon. The Fifth Dalai Lama was one of her greatest worshippers, the goddess is supposed to have appeared to him several times in person; she was his political advisor and confidante (Karmay, 1988, p. 35). One of her many names, which evoke both her martial and her tantric character, is "Great Warrior Deity, the Powerful Mother of the World of the Joys of the Senses” (Richardson, 1993, p. 87). After the “Great Fifth” had repeatedly recited her mantra for a while, he dreamt “that the ghost spirits in China [were] being subdued” (Karmay, 1988, p. 35). Since then she has been considered to be one of the chief enemies of Beijing.

In examining a portrait of her, one becomes convinced that Palden Lhamo would be among the most repulsive figures in a worldwide gallery of demons. With gnashing teeth, bulging eyes and a filthy blue body, she rides upon a wild mule. Beneath its hooves spreads a sea of blood which has flowed from the veins of her slaughtered enemies. Severed arms, heads, legs, eyes and entrails float around in it. The mule’s saddle is made from the leather of a skinned human. That would be repulsive enough! But the horror overcomes one when one discovers that it is the skin of her own (!) son, who was killed by the goddess when he refused to follow her example and adopt the Buddhist faith. In her right hand Palden Lhamo swings a club in the form of a child’s skeleton. Some interpreters of this scene claim that this is also the remains of her son. With her left hand the fiendess holds a skull bowl filled with human blood to her lips. Poisonous snakes are entwined all around her. [1]

Like the Indian goddess, Kali, she appears with a loud retinue. One can encounter her of a night on charnel fields together with her noisy flock. Just what unbridled aggression this army of female ghosts kindled in the imaginations of the monks is best shown by a poem which the lamas of the Drepung monastery sing in honor of their protective lady, Dorje Dragmogyel, who is one of Palden Lhamo’s horde:

You glorious Dorje Dragmogyel ... When you are angry at your enemies, Then you ride upon a fiery ball of lightning. A cloud of flames — like that at the end of all time - Pours from your mouth, Smoke streams from your nose, Pillars of fire follow you. Hurriedly you collect clouds from the firmament, The rumble of thunder pierces through the ten regions of the world. A dreadful rain of meteors and huge hailstones hurtle down, And the Earth is flooded in fire and water. Devilish birds and owls whir around, Black birds with yellow beaks float past, one after another. The circle of Mnemo goddesses spins, The war hordes of the demons throng And the steeds of the tsen spirits race galloping away. When you are happy, then the ocean beats against the sky. If rage fills you, then the sun and moon fall, If you laugh, the world mountain collapses into dust .... You and your companions Defeat all who would harm the Buddhist teaching, And who try to disrupt the life of the monastic community. Wound all those of evil intent, And especially protect our monastery, this holy place .... You should not wait years and months, drink now the warm heart’s blood of the enemies, and exterminate them in the blink of an eye.

(Nebesky-Wojkowitz, 1955, 34)

In our presentation of the tantric ritual we showed how the terror goddesses or dakinis, whatever form they may assume, must be brought under control by the yogi. Once subjugated, they serve the patriarchal monastic state as the destroyers of enemies. Hence, to repeat, the vajra master is — when he encounters the dark mother — not interested in transforming her aggression, but rather much more in setting her to work as a deadly weapon against attackers and non-Buddhists. In the final instance, however — the tantras teach us- the feminine has no independent existence, even when it appears in its wrathful form. In this respect Palden Lhamo is nothing more than one of the many masks of Avalokiteshvara, or — hence -- of the Dalai Lama himself.

We know of an astonishing parallel to this from the kingdom of the pharaohs. The ancient Egyptians personified the wrath of the male king as a female figure. This was known as Sachmet, the flaming goddess of justice with the face of a lioness (Assmann, 1991, p. 89). Since the rulers were also obliged to reign with leniency as well as justly wrath, Sachmet had a softer sister, the cat goddess Bastet. This goddess was also a characteristic of the king pictured in female form. Correspondingly, in Tibetan Buddhism the mild sister of Palden Lhamo is the divine Tara.

Even if the dreadful demoness is in the final instance an imagining of the Dalai, this does not mean that this projection cannot become independent and one day tear herself free of him, assume her own independent form and then hit back at her hated “projection father” as an enemy. Such radical “emancipations” of Tibetan protective deities are not at all rare and the collected histories of Tibet are full of reports, where submissive servants of the lamas free themselves and attempt to revolt against their lords. Right now, the Tibetan exile community is being deeply shaken by such a rebellious protective spirit by the name of Dorje Shugden, who has at any rate managed to disfigure the until now completely pure image of the Kundun in the West with some most persistent stains. We shall return to report on this often. From Shugden circles also comes the suspicion that Palden Lhamo has failed completely as the spiritual protector of Tibet, Lhasa, and the Dalai Lama, and has delivered the country into the hands of the Chinese occupiers. Whatever opinion one may have of such speculations, the extreme aggression of the demoness and the practical political facts do not exclude such a view of the matter.

In the life story of Palden Lhamo her relationship to her son is particularly cruel and numinous. Why a woman who is revered as the supreme protective spirit of Tibet and the Dalai Lama must be the slaughterer of her own child, may seem monstrous even to one who has become accustomed to the atrocities of the tantras. If we interpret the case psychologically we must ask ourselves the following questions: As a mother, is Palden Lhamo not driven by constant horror? Is her bottomless hate not the expression of her abominable deed? Must she not in her heart be the arch-enemy of Buddhism, the cause of her infanticide?

Is this repellant cult even more murderous than it already appears? Is the goddess perhaps offered sacrifices which simultaneously appease and captivate her? Since the demoness had to slaughter the utmost which a mother can give, namely her child, for Tibetan Buddhism, the sacrifice which is to fill her with satisfaction must also be the highest which Lamaism has to offer.

In fact, the early deaths of the Ninth, Tenth, Eleventh, and Twelfth Dalai Lama give rise to the question of whether a deliberately initiated sacrificial offering to Palden Lhamo could be involved here? All four god-kings died at an age before they were able to take over the business of government. In each case, the regents who were exercising real power until the new Dalai Lamas came of age were suspected with good reason of being the murderer. In the Tibet of old poisonings were a regular occurrence. There is even said to have been a morbid belief that whoever poisoned a highly respected man would obtain all the happiness and privileges of his victim.

These are the historical facts. But there is a mysterious event to be found in the brief biographies of the four unhappy “god-kings” which could lend their fate a deeper, symbolic meaning. We mean the visit to a temple about a hundred miles southeast of Lhasa which was dedicated to one of the emanations of Palden Lhamo. We must imagine such shrines (gokhangs), dedicated to the wrathful deities, to be a real cabinet of horrors. Stuffed full of real and magic weapons, padded out by all manner of dried human body parts, they aroused absolute repugnance among visitors from the West.

In order to test the psychological hardiness of the young Kunduns, at least once in their lives the children were locked in the morbid temple mentioned and probably exposed to the most terrible performances of the goddess. “Young as they were, they had insufficient knowledge to persuade her to turn away the wrath, which came so easily to her, and, accordingly, they died soon after the meeting”, Charles Bell wrote of this cruel rite of initiation (Bell, 1994, p. 159). Whatever may have taken place within this gokhang, the children emerged from this hell completely disturbed and were all four close to madness.

The lot of the young Twelfth was particularly tragic. His chamberlain, one of his few intimates, was caught thieving from the Potala on a large scale. He fled upon discovery of the deed, was caught up with, and killed. The body was strapped astride a horse as if it were alive. The dead man was thus led before the young Kundun. Before the eyes of the fifteen year old, the head, hands and feet of the wrongdoer were struck off and the trunk was tossed into a field. The god-king was so horrified by the spectacle of the body of his “best friend” that he no longer wanted to see anyone at all any more and sought refuge in speechlessness. Nevertheless, the visit to the horrifying temple of Palden Lhamo was still expected of him afterwards. In contrast the “Great Thirteenth” did not visit the shrine of the demoness before he was 25 years old and came away unscathed. Even the Chinese were amazed at this. We do not know if the Fourteenth Dalai Lama has ever set foot in the shrine.

If one pursues a Tibetan/tantric logic, it naturally makes sense to interpret the premature deaths of the four Dalai Lamas as sacrifices to Palden Lhamo, since according to tradition it is necessary to constantly palliate the terror gods with blood and flesh. The demoness’s extreme cruelty is beyond doubt, and that she desires the sacrifice of boys is revealing of her own tragic history. Incidentally, the slaughter of her son may be an indicator of an originally matriarchal sacrificial cult which the Buddhists integrated into their own system. For example, the researcher A. H. Francke has discovered rock inscriptions in Tibet which refer to human sacrifices to the great goddess (Francke, 1914, p. 21). But it could also– in light of the tantric methods — be that Palden Lhamo, converted to Buddhism not from conviction but because she was magically forced to the ground, was compelled by her new lords to murder her son and that she revenged herself through the killings of the young Dalai Lamas.

Even an apparently paradoxical interpretation is possible: as a female, the demoness stands in radical confrontation to the doctrine of Vajrayana, and she may have sold her loyalty and subjugation for the highest possible price, namely that of the sacrifice of the god-kings. Such sadomasochist satisfactions can only be understood from within the tantric scheme, but there they are — as we know — not at all seldom. Hence, if one set a limit on the sacrifice of the boys in terms of time and headcount, then they may have been of benefit to later incarnations of the god-king, specifically, that is, to the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Dalai Lamas. The exceptionally long reign of the last two Kunduns would, according to tantric logic, support such an interpretation.

In the mytho-historical pantheon of Tibetan Buddhism, the gentle goddess Tara represents the exact counterimage of the terrible Palden Lhamo. Tara is — in the words of European alchemy — the “white virgin”, the ethereal-feminine supreme source of inspiration for the adept. In precisely this sense she represents the positive feminine counterpart to the destructive Palden Lhamo, or hence to the earth mother, Srinmo. The divided image of femininity found in every phase of Indian religious history thus lives on in Tibetan culture. “Witch” and “Madonna” are the two feminine archetypes which have for centuries dominated and continue to dominate the patriarchal imagination of Tibet just like that of the west. If all the negative attributes of the feminine are collected in the witch, then all the positive ones are concentrated within the Madonna.

The Tara cult is probably fairly recent. Although legends recount that the worship of the goddess was brought to the Land of Snows in the seventh century by one of the women of the Tibetan king, Songtsen Gampo, it is historically more likely that the Indian scholar Atisha first introduced the cult in the eleventh century.

Unlike the many repellant demonic gods who attack the tormented Tibetans, Tara has become a place of refuge. Under her, the believers can cultivate their noble sentiments. She grants devotion, love, faith, and hope to those who call upon her. She exhibits all the characteristics of a merciful mother. She appears to people in dreams as a guardian angel. She takes care of all private interests and needs. She can be trusted with one’s cares. She helps against poisonings, heals illnesses and cures obsessions. But she is also the right one to turn to for success in business and politics. Everyone prays to her as a “redemptress”. In translation her name means “star” or “star of hope”. It can be said that outside of the monasteries she is the most worshipped divinity of the Land of Snows. There is barely a household in Tibet in which a small statue of Tara cannot be found.

A number of colors are assigned to her various appearances. There is a white, green, yellow, blue, even a black Tara. She often holds a lotus with 16 petals which is supposed to indicate that she is sixteen years old. Her body is adorned with the most beautiful jewels. In a royal seated posture she looks down mildly upon those who ask pity of her. Naturally, one gains the impression that she is not suitable for tantric sexual practices. The whole positive aspect of the motherly appears to have been concentrated within her. She is experienced by Europeans as a Madonna untouched by sexuality. This is, however, not the case, then in contrast to her occidental sister with whom she otherwise has so much in common, the white Tara is also a wisdom consort. [2]

Sometimes, as is also known of the European worship of Mary, her cult tips over into an undesirable (for the clergy, that is) expansion of the goddess’s power which could pose a danger to the patriarchal system. Tara is known, for example, as the “Mother of all Buddhas”. A legend in which she refuses to appear as a man is also in circulation and is often cited these days: when she was asked by some monks whether she did not prefer a male body, she is said to have answered: “Since there is no such thing as a 'man' or a 'woman', this bondage to male and female is hollow. ... Those who wish to attain supreme enlightenment in a man's body are many, but those who wish to serve the aims of beings in a woman's body are few; therefore may I, until the world is emptied out, serve the aim of beings with nothing but the body of a woman” (Beyer, 1978, p. 65). Such statements are downright revolutionary and are in direct contradiction to the dominant doctrine that women cannot attain any enlightenment at all, but must first be reborn in a male body.

Tantric Buddhism’s first protective measure against the potential feminine superiority of Tara is the story of her origin. Firstly, she does not have the status of a Buddha, but is only a female Bodhisattva. Her head is adorned by a small statue of Amitabha, an indicator that she is subject to the Highest Lord of the Light (who allows no women into his paradise) and is considered to be one of his emanations.

Furthermore, Tara is nothing more or less than the personified tears of Avalokiteshvara. One day as he looked down filled with compassion upon all suffering beings he had to weep. The tear from his left eye became the green Tara, that which flowed from his right became her white form. Even if, as according to some tantric schools, Chenrezi selects both Taras as wisdom consorts, they nevertheless remain his creation. He gave birth to them as androgyne, as “father-mother”.

An even cleverer taming of the goddess consists in the fact that she incarnates in the bodies of men. Countless monks have chosen Tara as their yiddam and then visualize themselves as the goddess in their meditative practices. “Always and in all practices, he must visualize himself as the Holy Lady, bearing in mind that the appearance is the deity, that his speech is her mantra, and that his memory and mental constructs are her knowledge” (Beyer, 1978, p. 465). Her role as the “mother of all Buddhas” is also taken on by the male meditators, who thus say the following words: “[I am] the mother who gives birth to the Conquerors and their sons; I possess all her body, speech, mind, qualities, and active functions” (Beyer, 1978, p. 449). In one of his works, Albert Grünwedel reproduces the portrait of a high-ranking Mongolian lama who is revered as an incarnation of Tara. Even modern western followers of Buddhism would like to see the Sixteenth Karmapa as the green Tara.

Like Palden Lhamo, Tara also plays a role in Tibetan realpolitik, then the latter is — in their own view — played out by gods, not human agents. Hence, the official opinion from out of the Potala was that the Russian Czars were supposed to be an embodiment of Tara. Such image transferences are naturally very well suited to exciting the global power fantasies of the lamas. Then, since the goddess arose from a tear of Avalokiteshvara, the Czar as Tara must also be a product of the Dalai Lama, the highest living incarnation of Avalokiteshvara. Further to this there is the idea derived from the tantras that the Czar (and thus Russia) as Tara could be coerced via a sexual magic act. This appears downright fantastic, but — as we know — the tantra master does use his karma mudra as symbols for the elements, planets, and also for countries.

In the nineteenth century the idea likewise arose that the British Queen, Victoria, was a reincarnation of Tara, yet on occasion Palden Lhamo was also nominated as being the goddess functioning behind the facade of the English Queen. It was thus more natural for the Dalai Lama to cooperate with the British or the Russians — since the Chinese had been possessed for centuries by a “nine-headed demoness” with whom it was impossible to reach an accord. The China-friendly Panchen Lama, however, saw this differently. For him, the Chinese Emperors of the Manchu dynasty, who professed to the Buddhist faith, were incarnations of the Bodhisattva, Manjushri, and could thus be considered as acceptable negotiators.

Tara and Mary:

A comparison of the Tibetan Tara with the Christian figure of Mary has by now become commonplace in Buddhist circles. The Fourteenth Dalai Lama also makes liberal use of this cultural parallel with pious emotionalism. For the “yellow pontiff” Mary represents the inana mudra (the “imagined female”) so to speak of Catholicism. "Whenever I see an image of Mary,” — the Kundun has said — "I feel that she represents love and compassion. She is like a symbol of love. Within Buddhist iconography, the goddess Tara occupies a similar position” (Dalai Lama XIV, 1996c, p. 83). Not all that long ago, the "god-king” undertook a pilgrimage to Lourdes and afterwards summarized his impressions of the greatest Catholic shrine to Mary with the following moving words. "There — in front of the cave — I experienced something very special. I felt a spiritual vibration, a kind of spiritual presence there. And then in front of the image of the Virgin Mary, I prayed” (Dalai Lama XIV, 1996 c, p. 84).

The autobiographical book with the title of Longing for Darkness: Tara and the Black Madonna by the American, China Galland, reports on the attempt to incorporate the Catholic cult of Mary via the Tibetan cult of Tara. After the author’s second marriage failed, she returned to the Catholic Church and devoted herself to an excessive Mary worship with feministic undertones. The latter was the reason why Galland felt herself attracted above all to the black Madonnas worshipped in Catholicism. The “Black Virgin” has already been worshipped for years by feminists as an apocryphal mother deity.

One day the author encountered the Tibetan goddess, Tara, and the American was instantly fascinated. Tara struck her as a pioneer of “spiritual” women’s rights. The goddess had — this author believed –proclaimed that contrary to Buddhist doctrine enlightenment could also be attained in a female body. The author felt herself especially attracted to figure of the “green Tara”, whom she equates with the black Kali of Hinduism at one point in her book: “The darkness of the female gods comforted me. I felt like a balm on the wound of the unending white maleness that we had deified in the West. They were the other side of everything I had ever known about God. A dark female God. Oh yes!” (Galland, 1990, p. 31).

In Galland we are thus dealing with a spiritual feminist who has rediscovered her original black mother and is seeking traces of her in every culture. In the Buddhist Tara cult this author thus also sees archetypal references to the many-breasted Artemis of Ephesus, to the Egyptian Isis, to the Phoenician Alma Mater, Cybele, to the Mesopotamian goddess of the underworld, Ishtar. Once more her trail leads from the dark Tara to the “black Madonnas” of Europe and America. From there the next link in the chain is the Indian terror goddess Kali (or Durga). “Was the blackness of the virgin a connecting thread of connection to Tara, Kali or Durga, or was it a mere coincidence?” asks Galland (Galland, 1990, p. 50). For her it was no coincidence!

With one word Galland activates the gynocentric world view which is familiar enough from the feminist literature. She sees the great goddess at work everywhere (Galland, 1993, p. 42). The universal position which she grants herself as the first creative principle is depicted unambiguously in a poem. The author found it in a Gnostic Christian text. There a female power, who sounds “more like Kali than the Mother of God”, says the following words:

For I am the first and the last. I am the honored and the scorned one. I am the whore and the holy one. I am the wife and the virgin

...

I am the silence that is incomprehensible

(quoted by Galland, 1990, p. 51)

In spite of her unmistakable pro-woman position, the feminist met her androcentric master in October 1986, who transformed her black Kali (or Tara or Mary) into a pliant Tantric Buddhist dakini. During her audience, for which she feverishly waited for several days in Dharamsala, she asked His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama: “Did it make sense to link Tara and Mary?” — “Yes,” — the Kundun answered her — “Tara and Mary create a good bridge. This is a direction to go in” (Galland, 1990, p. 93).

He then told the feminist how pro-woman Tibetan Buddhism is. For example, the Sakya Lama, the second-highest-ranking hierarch of the Land of Snows, had a wife and daughter. Somewhere in Nepal there lived a 70-year-old nun who was entitled to teach the Dharma. When he was young there was a famous female hermit in the mountains of Tibet. For him, the Dalai Lama, it made no difference along the path to enlightenment whether a person had a male body or a female one. And then finally the climax: “Tara” — the Kundun said — “could actually be taken as a very strong feminist. According to the legend, she knew that there were hardly any Buddhas who had been enlightened in the form of a woman. She was determined to retain her female form and to become enlightened only in this female form. That story had some meaning in it, doesn’t it?” — he said with “an infectious smile” to Galland (Galland, 1990, p. 95).

"Smiling” is the first form of communication with a woman which is taught in the lower tantras (the Kriya Tantra). The next tantric category which follows is the “look” (Carya Tantra), and then the “touch” (Yoga Tantra). Galland later reported in fascination what happened to her during the audience: “He [the Kundun) got up out of his chair, came over to me as I stood up, and took me firmly by the arms with a laugh. The Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, is irrepressibly cheerful. His touch surprised me. It was strong and energetic, like a black belt in aikido. The physical power in his hands belied the softness of his appearance. He put his forehead to mine, then pulled away smiling and stood there looking at me, his hands holding my shoulders. His look cut through all the words exchanged and warmed me. I sensed that I was learning the most about him and that I was being given the most by him, right then. Though what it was could not be put into words. This was the real blessing” (Galland, 1990, p. 96).

From this moment on, the entire metaphysical standpoint of the author is transformed. The revolutionary dark Kali becomes an obedient “sky walker” (dakini), the radical feminist becomes a pliant “wisdom consort” of Tantric Buddhism. With whatever means, the Dalai Lama succeeded in making a devout Buddhist of the committed follower of the great goddess. From now on, Galland begins to visualize herself along tantric lines as Tara. She interprets the legend in which the goddess offers to help her tear-father, Avalokiteshvara (Tara arose from one of the Bodhisattva’s tears), lead all suffering beings on the right path, as her personal mission.

The “initiation” by the Kundun did not end with this first encounter, it found its continuation later in a dream of the author’s. There Galland sees how the Dalai Lama splashes around in a washtub, completely clothed, and with great amusement. She herself also sits in such a tub. Then suddenly the Kundun stands up and looks at her in an evocative silence. “There was nothing between us, only pure being. It was a vivid and real exchange. — Suddenly a blue sword came out of the crown of the Dalai Lama’s head over and across the distance between us and down to the crown of my head, all the way down my spine. I felt as though he had just transmitted some great, wordless teaching. The sword was made of blue light. I was very happy. Then he climbed into the third tub, where I was now sitting alone. We sat side by side in silence. I was on the right. Our faces were next to one another, faintly touching” (Galland, 1990, p. 168). The Dalai Lama then climbs out of the tub. She tries to persuade him to explain the situation to her, and in particular to interpret the significance of the sword. “But every time I asked him a question, he changed forms, like Proteus, the old man of the sea, and said nothing” (Galland,1990, p. 169). At the end of the dream he transformed himself into a turquoise scarab which climbed the wall of the room.

Even if both of the dream’s protagonists (the Dalai Lama and China Galland) are fully clothed as they sit together in the washtub, one does not need too much fantasy to see in this scene a sexual magic ritual from the repertoire of the Vajrayana. The blue sword is a classic phallic symbol and reminds us of a similar example from Christian mysticism: it was an arrow which penetrated Saint Theresa of Avila as she experienced her mystic love for God. For China Galland it was the sword of light of the supreme Tibetan tantra master.

Soon after the spectacular dream initiation, the “pilgrimages” to the holy places at which the black Madonnas of Europe and America are worshipped described in her book began. Instead of Marys she now only sees before her western variations upon the Tibetan Tara. The tear (tara) of Avalokiteshvara (the Dalai Lama) becomes an overarching principle for the American woman. In the dark gypsy Madonna of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer (France), in her famous black sister of Czestochowa (Poland), in the copy of the latter in San Antonio (Texas), but above all in the Madonna of Medjugorje, whom she visits in October 1988, Galland now only sees emanations of the Tibetan goddess.

Whilst she reflects upon Mary and Tara in the (former) Yugoslavian place of pilgrimage, a prayer to the Tibetan deity comes to her mind. “In it she is said to come in what ever form a person needs her to assume in order for her to be helpful. True compassion. Buddha Tara, indeed all Buddhas, are said to emanate in billions of forms, taking whatever form is necessary to suit the person. Who can say that Mary isn’t Tara appearing in a form that is useful and recognizable to the West? When the Venerable Tara Tulku [Galland’s Buddhist Guru, a male emanation of Tara) came [...], we spoke about this. From the Buddhist perspective, one cannot say that this isn’t possible, he assured me: 'If there is a person who says definitely no, the Madonna is not an emanation of Tara, then that person has not understood the teaching of Buddha'. Christ could be an emanation of Buddha” (Galland, 1990, p. 311).

What lies behind this flowery quotation and Galland’s eccentric Mary-worship can also be referred to as the incorporation of a non-Buddhist cult by Vajrayana. Then Mary and Tara are both so culture-specific that a comparison of the two “goddesses” only makes sense at an extremely general level. Neither does Tara give birth to a messiah, nor may we imagine a Mary who enters sexual magic union with a Christian monk. Despite such blatant differences, Tantrism's doctrine of emanation allows the absorption of foreign gods without hesitation, yet only under the condition that the Tibetan deity take the original place and the non-Buddhist one be derived from it. In this connection, the report of a Catholic (Benedictine) nun who participated in the Kalachakra initiation in Bloomington (1999). For her, the rite set off a Christian experience: “I’m Christian. Never before has that meant so much. This past month I sat at the Kalachakra Initiation Rite in Bloomington with H.H. the Dalai Lama as the master teacher, a tantric guru. I have never felt so Christian. […] I was sitting in the VIP section on the stage very near the Dalai Lama. The Buddhist audience seemed like advanced practitioners. The audience was nearly 5,000 people under this one huge tent. When dharma students would know that I was a nun they’d ask me what was in my mind as the ritual progressed through the Buddhist texts, recitations, deity visualizations and gestures. At the time, I must confess, I sat with as much respect, openness and emptiness as possible. My Christian heart was simply at rest being there with ‘others’. […] There’s no one-to-one correspondence with Buddhist rituals especially one as complex and esoteric as the Kalachakra, but there is a way that we live that creates the same feeling, the same attitude and dispositions. (Funk,. HPI 001) The literature in which Buddhist authors present Christ as a Bodhisattva and as an emanation of Avalokiteshvara grows from year to year. We shall come to speak about this in the chapter on the ecumenical politics of the Dalai Lama.

The lament of Yeshe Tshogyal:

The tantric partner of Padmasambhava, the founding father of Tibetan Buddhism, is frequently offered as the historical example of a female figure who is supposed to have integrated all the contradictory powers of the feminine within herself. She goes by the name of Yeshe Tshogyal and is said to have achieved an independence unique in the history of female yoginis. Some authors even say (contrary to all doctrines) that she attained the highest goal of full Buddhahood. For this reason she has currently become one of the rare icons for those, primarily western, believers who keep a lookout for emancipated female figures within Tantric Buddhism.

The legend reports that Yeshe Tshogyal married the Tibetan king Trisong Detsen (742–803) at the age of thirteen. Three years later, he gave her to Padmasambhava as his karma mudra. Such generous gifts of women to gurus were, as we know, normal in Tantrism and taken for granted.

Yeshe Tshogyal became her master’s most outstanding pupil. When she was twenty years old, he initiated her in a flame ritual. During the ceremony the guru, in the form of a terror deity "took command of her lotus throne [the vagina] with his flaming diamond stalk [the penis]“ (quoted by Stevens, 1990, p. 70). This showed that she had to suffer the fate of a classic wisdom consort; she was symbolically burnt up.

Later she practiced Vajrayana with other men and subsequently underwent a long ascetic period as an “ice virgin” in the coldest mountains of Tibet. Like the historical Buddha she was also tempted by lecherous beings, it was just that in her case these were no “daughters of Mara” but rather handsome young devils. She recognized their lures as the work of Satan and resolutely rejected them. But out of compassion she subsequently slept with all manner of men and gave "her sexual parts to the lustful” (quoted by Stevens, 1990, p. 71). Her devotion in love is so convincing that she could convert seven highwaymen who raped her to Buddhism.

Padmasambhava is supposed to have said to her: "The basis for realizing enlightenment is a human body. Male or female, there is no great difference. But if she develops the mind bent on enlightenment the woman’s body is better” (quoted by Stevens, 1990, p. 71). This statement is admittedly revolutionary, but nevertheless we can hardly accept that Yeshe Tshogyal traveled an essentially different path to the countless anonymous yoginis who were “sacrificed” on the altar of Tantrism. [4]

Through constant visions she was repeatedly urged to offer herself up completely to her master — to sacrifice her own flesh, her blood, her eyes, nose, tongue, ears, heart, entrails, muscles, bones, marrow, and her life energy. One may also begin to seriously doubt her privileged position within Tibetan Buddhism, when one hears her impressive and resigning lament at her woman’s lot:

I am a woman I have little power to resist danger. Because of my inferior [!] birth, everyone attacks me. If I go as a beggar, dogs attack me. If I have wealth and food, bandits attack me. If I do a great deal, the locals attack me. If I do nothing, gossip attacks me. If anything goes wrong, they all attack me. Whatever I do, I have no chance for happiness. Because I am a woman it is hard to follow the Dharma. It is hard even to stay alive.

(quoted by Gross, 1993, p. 99)

Many centuries after her earthly death, Yeshe Tshogyal became for the Fifth Dalai Lama a constant companion in his visions and advised him in his political decisions. During a meeting, “Tshogyal appears in the form of a white lady adorned with bone ornaments. She enters into union with him. The white and the red bodhicitta [seed] flow to and fro” (Karmay, 1988, p. 54). Such scenes of union with her are mentioned several times in the Secret Visions of the “Great Fifth”. Some of these are described so concretely that they probably concern real human mudras who assumed the role of Yeshe Tshogyal. Once His Holiness saw in her heart “the mandala of the Phurba (ritual dagger) deity” (Karmay, 1988, p. 67). Perhaps she wanted to remind him with this vision of the agonizing fate of Srinmo, the Mother of Tibet, in whose heart a ritual dagger is also stuck. In another vision she appeared together with the goddess Candali and three further dakinis. They danced and sang the words “Phurba is the essence of all tutelary deities.” (Karmay, 1988, p. 67). [5]

Even if, as is claimed by many contemporary tantra masters and feminists, Yeshe Tshogyal is supposed to be the most prominent historical representative of an “emancipated” Vajrayana female Buddhist, her unhappy fate shows just how degradingly and contemptuously the countless unknown and unmentioned karma mudras of Tibetan history must have been treated. The example she provides should be more a deterrent than a positive one, then she was more or less an instrument of Padmasambhava’s. Her current rise in prominence is exclusively a product of the contemporary Zeitgeist, which needs to generate counterimages to an essentially androcentric Buddhism so as to gain a foothold in the western world.

The mythological background to the Tibetan-Chinese conflict:

Avalokiteshvara versus Guanyin:

We would now like to point out that, in the historical relationship between Tibet and China, the latter played and continues to play the feminine part, as if the sky-high mountains of the Himalayas and the Chinese river plains were a man and a woman in stand-off, as if a battle of the sexes had been being waged for centuries between “masculine” Lhasa and “feminine” Beijing. This is not supposed to imply that, in contrast to the patriarchal Land of Snows, a matriarchy has the say in China. We know full well how the “Middle Kingdom” has from the outset pursued a fundamentally androcentric politics and how nothing has changed in this regard up until the present. Hence, what we primarily wish to say here is that from a Tibetan viewpoint the conflict between the two countries is interpreted as a gender conflict. We hope to demonstrate in this chapter that the Dalai Lama is opposed by the threatening and ravenous “Great Female”, the terror dakini which is China and which he must conquer and subjugate along tantric lines.

The reverse cannot be so simply stated: the Chinese Emperor admittedly saw the rulers of Potala as powerful spiritual opponents, but understood himself thus only in a very few cases to be the representative of a “womanly power”. Yet such historical exceptions do exist and we would like to consider these in more detail. There is also the fact that China’s androcentric culture has been repeatedly limited and relativized by strong female elements. Real feminine influences can be recognized in Chinese mythology, in particular national philosophies (especially Taoism), and sometimes also in the politics, far more than was ever the case in the masculine Tibetan monastic empire. For example, Lao-tzu, the great proclaimer of the Dao De Jing, clearly stresses the feminine factor (or rather what one understood this to be at the time) in his practical “theory of power”:

Nothing is weaker than water, But when it attacks something hard Or resistant, then nothing withstands it, And nothing will alter its way. [...] weakness prevails Over strength and [...] gentleness conquers The adamant [...]

It says in the 78th chapter of the Dao De Jing. Among Chinese Buddhists the greatest reverence is up until the present day reserved for a goddess (Guanyin), a female Buddha and no god. China’s few yet famous/notorious female rulers in particular showed a unique tension in dealings with the kings and hierarchs of the Tibetan “Land of Snows”. For this reason we shall consider these in somewhat more detail. But let us first turn to the Chinese goddess, Guanyin.

China (Guanyin) and Tibet (Avalokiteshvara):

How easily the ambivalent gender role of the male androgyne Avalokiteshvara could tip over into the feminine is demonstrated by “his” transformation into Guanyin, the “goddess of mercy”, who is still highly revered in China and Japan. Originally, Guanyin had no independent existence, but was solely considered to be a feminine guise of the Bodhisattva (Avalokiteshvara). In memory of her male past she sometimes in older portrayals has a small goatee. How, where, and why the sex change came about is considered by scholars to be extremely puzzling. It must have taken place in the early Tang dynasty from the seventh century on, then before this Avalokiteshvara was all but exclusively worshipped in male form in China too.

There is already in the early fifth century a canon in which 33 different appearances of the “light god” are mentioned and seven of these are female. This proves that the incarnation of a Bodhisattva in female form was not excluded by the doctrine of Mahayana Buddhism. To the benefit of all suffering beings — it says in one text — the “redeemer” could assume any conceivable form, for example that of a holy saying, of medicinal herbs, of mythical winged creatures, cannibals, yes, even that of women (Chayet, 1993, p. 154). But what such exceptions do not explain is why the masculine Avalokiteshvara was essentially supplanted and replaced by the feminine Guanyin in China. In the year 828 C.E. each Chinese monastery had at least one statue of the goddess. The chronicles report the existence of 44,000 figures.

There is more or less accord among orientalists that Guanyin is a syncretic figure, formed by the integration into the Buddhist system imported from India of formerly more powerful native Chinese goddesses. A legend recounts that Guanyin originally dwelled among the mortals as the king’s daughter, Miao Shan, and that out of boundless goodness she sacrificed herself for her father. This pious tale is, however, somewhat lacking in vibrancy as the genesis of such an influential religious lady as Guanyin, but nonetheless interesting in that it once more offers us a report of a female sacrifice in the interests of a patriarch.

We find the suggestion often put forward by the Tibetan side, that the worship of Guanyin is a Chinese variant of the Tibetan Tara cult, similarly unconvincing, since the latter was first introduced into Tibet in the eleventh century, 400 years after the transformation of Avalokiteshvara into a goddess. In view of the exceptional power which the goddess enjoys in China it seems much more reasonable to see in her a descendant of the great Taoist matriarchs: the primordial mother Niang Niang, or the great goddess Xi Wangmu, or Tianhou Shengmu, who is worshipped as the “sea star”.

If Avalokiteshvara represents a “fire deity”, then Guanyin is clearly a “water goddess”. She is often pictured upon a rock in the sea with a water jug or a lotus flower in her hand. The “goddess on the water lily”, who sometimes holds a child in her arms and then resembles the Christian Madonna, fascinated the royal courts of Europe in the seventeenth century already, and the first European porcelain manufacturers copied her statues. Her epithets, “Empress of Heaven”, “Holy Mother”, “Mother of Mercy”, also drew her close to the cult of Mary for the West. Like Mary then, Guanyin is also called upon as the female savior from the hardships and fears of a wretched world. When worries and suffering make one unhappy, then one turns to her.

The transformation of Avalokiteshvara into a Chinese goddess is a mythic event which has deeply shaped the metapolitical relationship between China and Tibet. Historical relations of both nations with one another, although they both exhibit patriarchal structures, may thus be described through the symbolism of a battle of the sexes between the fire god Chenrezi and the water goddess Guanyin. What is played out between the gods also has — the tantras believe — its correspondences among mortals. Via the fate of the three most powerful female figures from China’s past, we shall examine whether the tantric pattern can be convincingly applied to the historical conflicts between the two countries (Tibet and China).

Wu Zetian (Guanyin) and Songtsen Gampo (Avalokiteshvara)

Following the collapse of the Han kingdom in the third century C.E., Mahayana Buddhism spread through China and blossomed in the early Tang period (618–c. 750). After this a renaissance of Confucianism begins which leads from the mid-ninth century to a persecution of the Buddhists. In the Hua-yen Buddhism of the seventh century (a Chinese form of Mahayana with some tantric elements), especially in the writings of Fa-Tsang, the cosmic “Sun Buddha”, Vairocana, is revered as the highest instance.