THE TEMPLES OF MOUNT LAWU AND THE PRODUCTION OF AMRITA

THE TEMPLES OF MOUNT LAWU AND THE PRODUCTION OF AMRITA

Of all the temples found in Java, there are perhaps no more blatant examples of Tantric iconography than those found on the slopes of Mount Lawu.

This mountain—actually a quiescent volcano—is on the border between Central Java and East Java, not far from the city of Surakarta (Solo) and easily accessible from Yogyakarta (Jogja). As one climbs into the foothills, the temperature becomes cooler and there is extensive agriculture in the form of terraced fields of tea and other commodities. A curving road hugging the side of the mountain takes the visitor past simple houses, an occasional ox, and scenery of incredible beauty. For centuries, Mount Lawu (or Gunung Lawu, in Javanese) has been a spiritual center, a kind of Indonesian Mount Shasta.

The people who live on the western slope of Mount Lawu practice Hinduism and have a local priest who officiates at Hindu rituals. The shrines and statues at the two temples under discussion—Candi Ceto and Candi Sukuh—are welltended. There are flowers left in front of statues, incense burning near trees or before stone phalluses, all left by unseen hands. Mount Lawu is a mystical site, and the temples of Ceto and Sukuh are especially potent. The temples are places of pilgrimage for traditional kejawen-type gurus and their students. Yet, for all their local popularity, they are rarely visited by foreign tourists.

The temples on Mount Lawu are believed to have been built during the 15th century CE, meaning that they were already in use when Columbus landed in North America. They represent a form of Tantra that had been fused with indigenous Javanese practices and reflect the tensions building in Java with the ascendancy of Islam during the same period.

To understand the cultural and religious environment that gave rise to these temples, it is necessary to know a little about the history of Java in the13th century, immediately before construction began at Candi Ceto and Candi Sukuh.

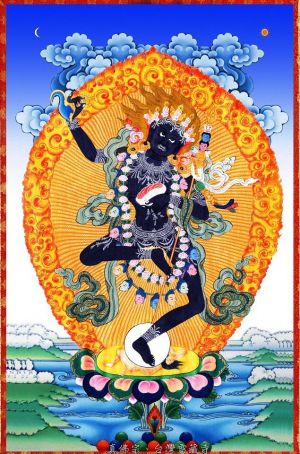

One of the most famous Tantric Javanese kings was Kertanegara, the last of the Singhasari dynasty. An initiate of Hevajra Tantra (which became one of the central Tibetan teachings), Kertanegara represented a fusion of Hinduism and Buddhism within a purely Tantric context. Indeed, he believed himself to be the avatar of both Shiva and Buddha. He was also one of the most notorious of all the Southeast Asian rulers of the period, for he openly opposed none other than the great Mongol emperor Kublai Khan.

School children know of the Great Khan from their study of the voyages of Marco Polo, who visited Kublai Khan's court. A grandson of Genghis Khan, Kublai sought to extend his empire throughout Asia and eventually turned his attention to the Javanese kingdoms to the south. He sent envoys to demand tribute from the court of Kertanegara, who promptly had the men arrested, cut off their ears, and sent them back to China, where the Khan reacted with predictable anger.

At the same time, Kertanegara had sent an army to Sumatra to subdue the Islamic kingdom of Jambi. Since Jambi had already formed an alliance with the Khan, Kertanegara assumed that it would align itself militarily with him as well. When the Khan's forces finally did arrive in Java around the year 1290, they found the Singhasari dynasty in disarray. A revolt had taken place against Kertanegara while his troops were off fighting the Jambi kingdom in Sumatra. Kertanegara was himself slain during a Tantric ritual at which large quantities of wine had been consumed, rendering him and his retinue intoxicated and defenseless.

The rebellious commander was eventually slain by Kertanegara's son-in-law, the Raden (Prince) Wijaya, who not only defeated the rebel armies, but also managed to rout the Mongol forces sent by the Khan. It was through Raden Wijaya's line that the last non-Islamic dynasty of Java, the Majapahit, was founded in 1293. This dynasty lasted for over 200 years, during which time most of present-day Indonesia as well as present-day Malaysia were incorporated within the Majapahit empire. It was in the later period of this dynasty that the famous and mysterious Tantric temples of Candi Ceto and Candi Sukuh were built and consecrated, probably during the reign of King Brawijaya V, the last monarch of the Majapahit and thus the last non-Islamic monarch in Java. As enemy forces began squeezing the armies of the Majapahit, many fled to neighboring Bali, where the Hindu way of life and religion was preserved. Others wound up scattered throughout Java, hiding in the mountains and building their temples and shrines to the Javanese-Hindu-Buddhist religion they practiced so faithfully.

Candi Ceto and Candi Sukuh are two of these temples. They remained largely forgotten and in ruin until the 19th and 20th centuries, when foreign officials took note of the sites and began excavation and restoration. The sites were still revered by the people who lived on Mount Lawu, who regarded them as sources of spiritual power.

We will look at Candi Ceto and Candi Sukuh in turn.

Candi Ceto The photo below shows the entrance to the temple—a lintel-less gate that is typical of Javanese religious architecture. The stone figure at the entrance, called Nyai Gemang Arum, does not appear to be a guardian, but a devotee.

Nyai is a term of respect for women, especially women of high social rank, although the statue in this case does not appear to be female. In Bali, the same term may be used to signify “you” or “thou,” also terms that imply respect for someone of higher social status. Thus the confusion may rest there, as the Balinese were and are devout Hindus and Candi Ceto is a Hindu-Javanese shrine.

Compare this statue to the two others on the facing page that flank the main entrance. They are called Nyai Agni, which may be a reference to the Sanskrit word for “fire” (agni) and which is also the name of the God of Fire in Hinduism, both of which are male. The Hindu deva Agni is usually shown with two heads or two faces. The fact that there are two Nyai Agni here may be a reference to this, but the religious symbolism of the temple has been so Javanized that any clear association between it and classical Indian religion is a bit problematic.

To add to the confusion, the restoration of the temple was conducted in a cavalier fashion. All of the wooden elements had, of course, deteriorated to the point that new wooden roofs, beams, and structural supports had to be made. Much of the stonework was in disarray as well, leaving some of the reconstruction design up to the imagination of the workers. However, enough elements of the original Candi Ceto (begun about 1451) remain to allow us to develop theories about the purpose for the entire site.

At the top of page 139 is one of the two Nyai Agni found at Candi Ceto. From the beard, we can assume that the figure is not female. However, the statue is back-to-back with a female figure, shown in the second image, that is not identified, thus adding a greater degree of confusion. Notice also the offering of rice and incense that has been made to the statue. What appear to be wristwatches on either arm of the figure have contributed to some hilarity among some visitors.

The second Nyai Agni at Candi Seto, shown opposite below, is in much disrepair, but also sports facial hair.

On page 82 we see the Candi Ceto temple complex as it appeared in 2008. All of the wooden structures are, of course, new and part of the restoration work that was begun in 1970.

On page 140 is another view of the complex that gives some idea of the layered effect of the fourteen terraces that made up the original design. Only thirteen of the terraces remain at the present time.

The complex contains two statues of historical figures, advisors to the last king of the Majapahit dynasty. They are shown on page 141. The first is Sabdapalon, a loyal subject of King Brawijaya V, and a priest as well as a spiritual and political advisor. According to the story, he cursed the king when the latter converted to Islam in the year 1478. He foretold that the Hindu-Javanese kingdom would return in 500 years, but not before widespread devastation on Java. The 1978 eruption of Mount Semeru—also known as Mahameru or Mount Sumeru, after the Indian original—was believed to be one sign that the prophecy was being fulfilled.

The second statue is of the advisor Naya Genggong, who is sometimes believed to be one and the same person as Sabdapalon.

Because of the prophecies made by Sabdapalon, recorded in an ancient document entitled Ramalan Sabda Palon Naya Genggong (The Prophecy of Sabda Palon Naya Genggong), and the latest eruption of Mount Merapi outside of Yogyakarta in November 2010, there has been a resurgence of interest in this narrative and, consequently, something of a mystical revival taking place at the temples on Mount Lawu. Sabdapalon himself is believed to have left Java for the island of Bali, where Hinduism still flourishes, but so many stories are told about him that he has acquired a mystical status in his own right.

One of the few surviving reliefs at Candi Ceto shows what may be a typical scene from the shadow puppet theater. In the center of this stone is what appears to be Mount Meru, the cosmic mountain of Indian religion, depicted in wayang fashion. At either side are archers. This may be a scene from the Ramayana, but the erosion that has taken place has made it difficult to make out much detail.

Palang

One of the most shocking elements of Candi Ceto is the huge stone lingga and yoni on one of the terraces that marks the entrance to the main building. As you can see opposite, these lie flat on the ground rather than standing vertically, and their sheer size is arresting. The photo on page 144 shows a close-up of some curious ornamentation found on the lingga in the form of round balls or spheres at the head of the phallus, below the glans at either side and on top. This may reveal a cultural practice called palang.

Palang is a practice known in one form or another throughout Southeast Asia, but also mentioned in the Kama Sutra.14 It is a practice that involves the insertion of a rod in the penis—laterally, perpendicular to the head of the penis and just below the glans—and the attachment of small balls or beads on either end of it. This is supposed to increase female enjoyment during the sex act. The method has undergone a renewal in the modern world, much like piercing the body in other areas, like the tongue, navel, and breasts. After the first incision, a small length of bamboo is inserted to keep the wound from closing. When the sex act is to be performed, the bamboo is removed and replaced with a metal rod and the two balls attached, one at each end.

Other methods involve the insertion of precious stones, pearls, or gold balls in the skin of the penis where they usually remain.15 In some cases, small bells, ball bearings, and even silicon are inserted. The use of semi-precious stones, gold, and pearls is believed to provide the added benefit of increasing supernatural power, while also advertising the bearer's wealth and social status, thus increasing his desirability as a potential husband or mate.

Another supposed benefit of palang is the ability to remain in sexual intercourse for hours at a time.16 That is one of the Tantric ideals, of course, just as prolonged periods of meditation are considered evidence of the supernatural power and sincerity of the practitioner.

Palang has profound implications for the way in which Tantra was understood in Java at that time. The method of palang does not provide much enjoyment to the male; its purpose is strictly to increase stimulation in the female partner. The number of rods and balls can be considered signs of status—two, three, or more such rods could be inserted in the penis, with the respective number of balls; or a large number of balls or jewels could be directly and permanently inserted under the skin of the penis. This degree of attention to the female experience in the sex act indicates a focus on the female and her enjoyment that seems to be inconsistent with generally accepted ideas concerning patriarchal societies and their emphasis on the male orgasm. For instance, in cultures where “female circumcision” (clitoral mutilation) is practiced, something like palang would be inconceivable.

Why, then, would this practice attain the elevated status it enjoys in the stone sculptures of Candi Ceto? Is there another level of meaning that escapes the uninitiated observer? After all, these are not the usual phallic monuments we expect to see in Shiva temples. Lingga and yoni are prevalent throughout the Indian cultural sphere. Yet, it seems that we find lingga pierced in the style of palang only in Java (and Bali).

A possible answer will become clear as we move through the very detailed stonework of the temple, for Candi Ceto, like its sister Candi Sukuh, was designed for a very specific purpose—the collection of amrita.

The sculptures and iconography at Candi Ceto are very selective. All the symbols found there today can refer to one concept only—amrita—and the methods used to collect it. The juxtaposition of the lingga (with palang) and yoni, next to what appears to be a giant Garuda indicates that the entire complex was dedicated to this most Tantric of Tantric rituals. In order to decode it—and Candi Sukuh—we need to understand a bit more about the mysticism concerning biological fluids that was current in Indian Tantra and alchemy.

We can isolate two separate phenomena that take place in the context of Tantric worship and ritual, and specifically of the pancatattva or Five Elements ritual that incorporates sexual intercourse. One of these is the sex act itself, which may be considered from a psycho-biological viewpoint as the mating of two humans in an intense and focused ritual that may even take place before the gaze of onlookers (other members of the Tantric circle). Like the sex act between two people in love with each other, this act is both passionate and “animal,” but also contains higher elements, like a desire for union that transcends the physical. In that sense, the Tantric ritual of Maithuna is a kind of re-enactment of the moment when two lovers first embrace, as opposed to a sex act that takes place, for instance, between a prostitute and her client, or between a rapist and his victim.

This is the element of the Tantric rite that is pure consciousness, a symbol of the creation of the world (and of the specific creation—i.e., the conception—of the two individuals performing the rite). The moment of orgasm is usually delayed for a long period of time so that the partners reach a plateau of experience—much like an intense state of meditation that can last for hours or even longer—during which both partners lose themselves completely in the act, to the extent that it is difficult to know where one body ends and the other begins. Orgasm, if and when it occurs, can be intense, breath-taking, and, in some cases, truly illuminating.

The second phenomenon derives from the first, and involves the use and even the consumption of the bodily fluids created by the sex act. This is the element of Tantra that is often overlooked or ignored—if it is even understood or recognized—by practitioners of New Age Tantra, who focus primarily on improving their sexual experience and their relationships with lovers. However, it is as important to the process as the sexual act itself, for, just as sex often leads to conception and procreation—that is, the materialization on the physical plane of what began as something ephemeral like desire, lust, or love—so the Tantric act must also lead to a kind of procreation or materialization. And just as the sex act within the Tantric circle mimics the Ur-intercourse of the gods that led to the creation of the cosmos, so are worlds created through the medium of the sexual fluids.

We cannot understand some of the Western alchemical writings unless we recognize the importance of physical substance and its potential for transformation. The same true in Tantra. The seminal fluid, mucoid excretions, and blood that may be the effluvia of the sex act are all preserved or, in many cases, consumed on the spot by the practitioners. There is, actually, no bodily excretion at all that is considered tabu in the Tantric context.

The exoteric explanation is usually the recognition that the initiated adept has gone beyond a dualistic view of creation, and sees bodily excretions as no different from a field of wildflowers or a lover's sigh. All is Maya; all is illusion—the manifestation of desire in the created, albeit illusory, world. All is one; there is no difference between you and me. Thus, there is no reason to feel disgust at the sight of fecal material, just as there is no reason to feel desire at the sight of a beautiful person. There is no beauty, no ugliness. This is the exalted state of advaita, or nonduality. To demonstrate that one has achieved this state, one can as easily consume menstrual blood as a glass of wine.

The esoteric explanation is somewhat more mechanistic. If we make a general (and by no means adequate) distinction between the exoteric and esoteric as the mystical versus the magical, we may say that the esoteric explanation in this case is purely magical. It involves the conscious manipulation of reality to create new forms of reality. In a purely Buddhist sense, this may seem horrible, of course. The Buddhist goal is to transcend reality, to recognize “reality” as a concept without special spiritual attributes; reality is something inherently useless to those on the path. The multiplication of states of reality would seem, then, to be demonic, when viewed from the point of view of a Theravadin—if the Theravadin believed in the objective existence of demons, that is.

However, not everyone has the luxury of retreating from society and engaging in the quest for enlightenment. This is especially true of those who are in positions of power or authority—like kings or generals—and who feel a responsibility to their people and their professions. While some monarchs did retreat from the world, it was usually a temporary measure designed to enable the king to find his center, his source of power. Thus, we find that heads of royal houses in India as well as in Java engaged in Tantric rituals to ensure the fertility and security of their kingdoms.

As Indologist David Gordon White has demonstrated, Tantra was not a purely symbolic practice, with the sex act idealized in some way and visualized by monks in solitary cells as a divine process far removed from the comparatively more bestial act experienced by householders and outcastes.17 Tantra was flesh and blood—quite literally—and was a practice that made use of every aspect of the human experience, with a focus on the biological. Eating, drinking, breathing, excretion, and sexuality were all parts of the doctrine and were elements of the rituals. Much ink has been spilled over this issue. For a long time, the first Western observers in India, the British colonialists, either denigrated these ideas or simply refused to accept that the prescriptions in the Tantric texts were meant to be taken literally. The most famous of these commentators were Sir John Woodroffe, who wrote under the nom de plume Arthur Avalon, and Max Mueller, whose Sacred Books of the East was a milestone in Indological and other Asian research and scholarship. These authors either framed this potentially shocking material in a purely spiritualized way (Avalon) or simply omitted some of the most disturbing references altogether (Mueller). They may have believed they were doing Mother India a favor by presenting their sacred texts in the most positive light possible, but, in the process, a central element of these practices was dropped from the discussion, with the result that generations of students of Asian culture were left with a skewed perception of the subject. Much of this was due, also, to the reluctance of Indian scholars themselves to acknowledge this aspect of Tantra, either because they were staunch Vedic Brahmins for whom Tantra was a suspect practice, or because they feared British disapproval and reproach.

This was not so among the esotericists, however. A hundred years ago, secret societies like the Ordo Templi Orientis in Germany and the Hermetic Brotherhood of Light in Europe, the Middle East, and America insisted not only that the sexual act itself was a core ritual intended to be performed actually rather than simply visualized, but that the bodily fluids present or created during the sex act had magical potency and should be retained in some manner or consumed under the appropriate circumstances. At the same time, however, neither of these groups or the others involved in this practice ever assumed that all they had to do was perform sexually and somehow that would be sufficient to procure enlightenment and attain occult powers.

The spiritual, magical aspect of the sex act was the essential aspect of the ritual—not the sex alone, but the sexual act ritualized to the extent that both participants were spiritually prepared. This usually happened either through personal meditation or study, usually at the direction of a teacher—someone who had already gone through these experiences, or through a specific series of initiations—or both. The act itself was surrounded with all the impedimenta of occult ceremony: incense, chanting, etc. The timing and pace of the ritual was just as important and, far from being trivialized, was rather subject to scrutiny and almost obsessive attention to detail. In other words, the ritual was made to conform to what we would today call “laboratory conditions,” if that is not too secular a framing of what takes place in an occult ritual. In fact, the terminology is apt if we remember that Western alchemy may be based on just such an esoteric interpretation of sexuality—a laboratory for the transformation of matter.

Whereas Western alchemy is couched in chemical language and metaphor, Tantra is framed in biological language and metaphor. The bodily fluids so prized in Tantra have their correlates in the chemicals valued by the alchemists. The two cultures were essentially discussing the same secret and, at times, using virtually identical language to do so. The later European secret societies understood some of these equivalents, but it is not clear that they had the complete key to the process.

The major components were, of course, seminal fluid and menstrual blood. Initiates, however, were concerned, not only with the grosser aspects of these two elements, but with their “etheric” counterparts. While menstrual blood was valued as an essential component of the elixir vitae, or amrita, it was believed that the female genital organ was the source of other “essences,” depending on its time within the menstrual cycle. These essences were called kalas, a reference to the Sanskrit word for “time,” as well as to “essence” and “unguent” (kala). It was believed there were sixteen of these kalas, based on the sixteen “digits” of the lunar cycle in Indian astrology and hence related to a similar division of a woman's menstrual cycle. Thus, at different times of her period, a woman “excretes” a different kala, a different essence. This, of course, would be of intense interest and subject to observation by Tantric practitioners, who would time rituals of collection of these essences for optimum results.

The importance that the Javanese Tantricists gave to this concept is evident in their obsession with the mythical hero Garuda and with the story of how Garuda seized the amrita—the elixir vitae—from the grasp of the Nagas, the serpent gods. Depictions of Garuda are found everywhere in Indonesia, of course; their national airline is named after him. In Java, however, Garuda appears in a somewhat different form from the way he is normally shown in India and even in Bali. In Java, Garuda is thin, tall, even gangly. He has the head and talons of a bird of prey, and the body of a man. He is almost always shown with his claws on the backs of serpents and with the vessel of the precious amrita within reach of his talons.

At Candi Sukuh—arguably one of the most blatantly Tantric of all Javanese temples—Garuda is present in various forms throughout the complex. In the photo on the facing page, the heart-shaped instrument at his waist is the vessel of amrita. Considering that Candi Sukuh is where we find shrines to the phallus and statues of men with prominent members, the Garuda statues, with their serpent bases and their vessels of amrita, can only have been understood in a purely Tantric sense—especially as the sacred vessel itself is shown tied to Garuda's belt and dangling in front of his groin, as if it were a heart-shaped fig leaf, as the photograph shows.

In this case, the statue has been beheaded—possibly by art thieves—but the rest of the image is clearly that of Garuda, from his wings to his talon-like feet and the amrita vessel at his waist.

There are, of course, at least two different approaches to the concept of amrita. Like the quotation from Dr. Strangelove above, there is one school that cautions practitioners to retain their “precious bodily fluids” rather than lose them in the sex act. In this case, the male either refrains from ejaculation altogether or draws the ejaculated seminal fluid from his partner's vagina back through his penis into his own body. The latter practice requires long training and is potentially quite dangerous, as it reverses the normal action of the genital organ, making it, in effect, a kind of vacuum cleaner. The safer approach is to refrain from ejaculation and retain the seminal fluid, coaxing it (or, more correctly, its etheric counterpart) to enter into circulation in the body, raising it to the level of the pineal gland in the brain. This practice is well-known to practitioners of Hatha yoga and, in particular, Kundalini yoga.

Those who are familiar with Kundalini yoga remember that the goddess Kundalini is represented by a serpent. The serpent is made to rise through the seven levels of the human etheric body—the seven chakras—in order for initiates to attain enlightenment. This association of a serpent with the vital force, or amrita, is found in the stone carvings at Candi Sukuh representing the mission of Garuda, who stole the elixir from the serpent gods, the Nagas. The iconography is remarkably consistent with what we know of the actual practice of Tantra.

To give an idea of the creation of amrita from the churning of the cosmic ocean, we have the following photographs, which were taken in Bangkok Suvarnabhumi International Airport in 2008 of a huge sculpture commemorating the event as it appears in the Mahabharata.18 The first two show the serpent king—Ananta or Shesha—with many heads and his demonic devotees (the asuras) pulling him in a weird tug-of-war with the divine warriors (the devas). The third photo shows us a close-up of the churning Milk Ocean, in the midst of which we see a turtle, with the coils of the serpent on top. This particular juxtaposition of turtle, serpent, and elixir vitae (and Milk Ocean) is one we will come across again—particularly in the case of Candi Ijo and its mysterious shrine to creation itself.

In the foreground of the churning Milk Ocean on page 153, you can see a conch on a pedestal. It is believed that the conch was the first created form to emerge from the ocean, followed by the goddess Lakshmi. The conch symbolizes life itself and is an important element in many Hindu rituals, or puja, where it is used either as a horn (much like the shofar is used in Jewish ceremonies) or as a vessel for holding sacred water. Vishnu is often shown holding a conch in his hand, as in the detail from the sculpture on the facing page.

Thus, as we have seen, there are two important narratives concerning amrita. The first is the Churning of the Milk Ocean, which produces amrita; the second is the theft of amrita from the Nagas by the mythical bird-man Garuda. In both of these narratives, serpents (Nagas) are essential elements. Turtles also appear, forcing us to ask the obvious question: What is the relationship between amphibious creatures and the production/procurement of amrita?

In the following photograph, we can see some detail of the “yoni” figure that accompanies the lingga-palang figure at Candi Ceto. In the center of the yoni triangle can be seen a crab (another amphibious creature) with what appear to be three frogs in the very center of the sculpture. At the ends of the triangle barely can be seen the figures of lizards.

We can conclude that it requires the assistance of amphibians to obtain the amrita, for it is hidden in the ocean. Both the turtle and the serpents are essential to the story of the Milk Ocean. The addition of crabs and lizards (and possibly frogs) to the large stone emblem at Candi Ceto seems to place emphasis on this aspect of the story. Our attention is being drawn to this part of the code in a very deliberate manner.

In the next two photographs of an unnamed shrine at Candi Ceto, we see the use of turtles once again. They seem to be functioning as steps, but I am not comfortable with that description. They may serve a sacrificial purpose and, as can be seen, offerings of flowers and incense were made some time before my arrival.

In fact, the large sculpture of a Garuda that is flat on the ground next to the lingga-yoni bears yet another turtle on its back, as can be seen in the photo on the next page. The turtle's head can be seen rising from the circular form atop the large, winged sculpture lying flat to the rear of the yoni. Between the Garuda-cum-Turtle and the triangular yoni, there is a small circular sculpture representing a solar disc with seven rays. This was the symbol of the Majapahit dynasty.

The yoni in this sculpture is virtually crawling with amphibious creatures, and Garuda is himself carrying a huge turtle on his back. This is excessive, even by Tantric standards, unless a point is being made. The ability to rise from the sea to dry land and to return indicates that amphibians are liminal creatures, like divine kings and juru kunci. They thus have a special affinity as shamanic totems. Birds can be seen as liminal in the sense that they fly, and this may be why both a bird—Garuda—and a turtle are involved in the amrita narratives. If present-day paleo-zoological theories are true, dinosaurs are the direct ancestors of birds, which indicates an even greater degree of liminality—a connection with an ancient time and with a world where humans did not yet exist.

This idea of liminality may be enough for a general appreciation of the iconography, but when it comes to Tantra, there are always deeper levels of meaning. Tantra is about action and action is the manifestation of process—and this specific process involves fluids of various kinds.

The human foetus begins its existence as an amphibian, living in the fluidfilled sac of its mother. Even earlier, it is created through the mingling of fluids from both parents. When the infant is born, there is an expulsion of more fluid from the mother, and the almost ritualistic bathing of the newborn. These associations were not lost on those who created the Tantric worldview. They understood that there was a power in these specific fluids that far exceeded their appearance as mere bodily excretions. Blood and semen became the Red and the White tinctures of alchemy, of course, but the esoteric philosophers and alchemists who began this investigation did not stop there. They extended their research to other bodily excretions as well, including urine and feces, but also vaginal secretions at various times during a woman's period. They attempted to understand precisely which organs and other elements of the human body owed their creation to the male contribution of fluid, and which to the female essence. Attempts were made to synchronize bodily rhythms to solar and lunar patterns, to create complex matrices that would enable practitioners to caress the entire web of existence and provoke one or another response based on their understanding of the process.

Once it was understood that such a matrix did exist, the realization set in that it existed in every aspect of human experience—biological, psychological, chemical, spiritual, physical, architectural, musical, even political. Hence the elaborate calculations and iconography at Chartres Cathedral in France, for instance, which contains much alchemical symbolism in the form of statues and other images, but which also was built as a kind of device for enhancing the spiritual experience according to the mysticism associated with its geometrical proportions—what in Asian religion is called mandala. The science behind the creation of these mandalas in stone is known as Vastu in India, and the mathematical and geometrical considerations that go into their design are specific to their purpose. Candi Ceto and Candi Sukuh—as well as Borobudur, Prambanan, and other monuments in Java—were designed with a goal similar, if not identical, to the Gothic cathedrals of France.

Less than a mile from Candi Ceto is Candi Sukuh. This temple is so notorious that one Indonesian academic felt compelled to write an article entitled “Candi Sukuh is not a Porno Temple.”19 To be sure, there are even more Tantric references at Candi Sukuh than at Candi Ceto. The photograph of a headless man clutching his em-palanged phallus opposite represents only one of them.

While Candi Ceto's main iconography was the lingga-yoni and Garuda sculptures flat on the ground, at Candi Sukuh we have an extensive inventory of reliefs in a typical Javanese (rather than Indian) style. As you can see in the image above, we also have some interesting architecture that many visitors have associated with a type of design more common in Mexico and Central America than in Southeast Asia, which has given rise to all sorts of von Daennikenesque speculation.

These reliefs are informative, for they emphasize once again the relation of these temples to the gathering of amrita. Considering the time at which they were built—toward the end of the last Hindu-Javanese dynasty—one could also claim that their builders’ obsession with amrita and with associated ideas of immortality, health, power, and fertility seem nearly desperate. It may be this very desperation in the face of imminent collapse that led the builders to reveal more of the secrets than they might have otherwise.

The reliefs depict scenes from various stories familiar to audiences of the wayang kulit, the shadow theater. Prominent among them are Semar and other Java nese personalities, including several strange Garuda figures that actually may or may not represent Garuda, as well as ithyphallic reliefs of various types. Unfortunately, the same haphazard restoration work that plagued Candi Ceto is also evident at Candi Sukuh.

According to published reports, there were “scores” of yoni figures at Sukuh, but the workers who managed the restoration had no idea where to put them, so instead they stacked them in a warehouse. The yoni were made in the typical Indian style, “with a groove for water to flow through ... these were used to collect and make holy water ...”20

In the Indian religious context, “holy water” is, of course, amrita.

In addition, the main lingga—nearly six feet in height, and complete with palang balls—that stood at the entrance to Sukuh was removed and brought to the National Museum. Therefore, in order to understand the complete design, one has to visualize the replacement of these critical structures. What is presented, then, is a temple to the sacred sexuality of Java.

On the opposite page are three photographs that show the structure at Sukuh. The first shows one of the wooden gates erected by the temple custodians. Above the gate is the inevitable guardian, shown close-up in the second image. The style more closely resembles those of Bali than the previous examples at Borobudur and Prambanan. The third shows the other side of the shrine, with another set of wooden gates and the obligatory guardian at the top. At the left of the picture, you can see a figure with an exposed (and uncircumcised?) penis. The photo at the top left of page 164 gives us a closer look at this enigmatic creature.

On the other side of the gate there is another figure, shown top right on page 164, in a serpentine motif. These odd, almost surreal, images are believed to be chronograms, or candrasangkala in Javanese. They are a graphic method of stating the year in which the edifice was completed. It is a kind of Javanese Kabbalism, in which an image represents a word and that word represents a number. This one—which shows an elephant, a serpent, and other images—is understood as representing the year 1378 in the Saka (Hindu) calendar, or 1456 CE. While this interpretation is certainly accepted by most scholars, there are those who see in the use of these symbols something deeper than the calendar.21 That may be because the range of numbers is limited to the digits 1 through 9, but the number of words that can be used to represent numbers varies widely and seems to be at the discretion of the person creating the chronogram.

Thus at Candi Sukuh, we find images—representing words, which themselves represent numbers—that seem to be consistent with the theme of the temple and that are not merely “dead” numbers. An elephant swallowing a snake is representative of the Tantric nature of the site, for both elephants and serpents are very much in evidence in the other reliefs and have decidedly Tantric associations. The type of word-play involved in developing these chronograms will be familiar to anyone who has studied Western alchemical literature, as well as to those familiar with the elaborate word games found in the Zohar. It's one example of the twilight language that we described earlier, which serves both to conceal and reveal the intentions of the creators.

In the photograph on page 165, we find what the wooden gates are protecting—a lingga-yoni figure on the floor of the shrine, at the entrance where visitors would have had to step over it in order to get into the inner areas. In this case, the lingga is clearly piercing the yoni. No ambiguity here. The yoni is roughly heart-shaped, with what appear to be fingers at either side, and the whole image is surrounded by what may be a serpent or serpentine motif with eleven coils. The debris that can be seen in and around the figure are the remains of flower offerings.

Taken as a whole, the lingga-yoni depicted here resembles a chalice with the lingga as the stem and the yoni as the cup. Considering some of the speculation that has surrounded the identity of the Holy Grail in Western esoteric literature, this device may very well add another level of interpretation.

There are several narratives displayed on the reliefs at Candi Sukuh—several different myth cycles that reflect legends common to Javanese culture and to the wayang kulit performances. In fact, the figures at Candi Sukuh are almost certainly based on the designs of the leather puppets that are used throughout Java even today. Their departure from traditional Indian styles is obvious and dramatic, yet their themes remain remarkably consistent with Indian Tantra.

The story of Sudamala, the first of these narratives, bears some explanation. As usual, it centers around the relationship between Shiva and his consort, Uma. In this case, Shiva wanted to make love to Uma, but she refused him on the basis that the time was inappropriate. Angered, Shiva cursed Uma, turning her into the dreaded Bathari Durga. Durga, of course, is the demonic form of Uma. Desperate to have the curse removed, she turned to the five Pandawa brothers (heroes of the Indian epic Mahabharata). Impersonating their mother, she asked them to purify her. One of the brothers, known as Sadhewa, agreed and she was purified.

The transformations of gods and goddesses is well-known in world religions. The Greek gods frequently transform into animals or humans. Transformations can tell us a great deal about the personalities, powers, and functions of the deities involved. In the case of Uma, she has already been transformed from Parvati. Now, under the curse from Shiva, she undergoes another transformation, this time to become a creature of the Underworld. Yet even that transformation is only a preliminary to her next incarnation as the mother of the five Pandawas.

The message of the transformation of divinity may be a way of expressing immanence—the presence of the divine in ordinary events, average persons, the environment, etc. Moreover, there is an implied reciprocal process—that of the average, the ordinary, the mundane becoming divine through transformation. This is the core concept in alchemy, whether of the chemical, the biological, or any other form. While the religious experience is largely one of submission to the will of God, the esoteric approach allocates to itself the ability—and the courage, or foolhardiness—to become God.

The narratives in stone that we find at Candi Sukuh and Candi Ceto are decidedly the latter. There is no sense of submission to divine will in these temples. They were designed to be active machines for the transformation of consciousness through the manipulation of symbols known as ritual.

In the Sudamala narrative, we have a transformation from the demonic to the divine facilitated through the use of water, the purifying substance par excellence. The scores of yonis discovered at Candi Sukuh imply an aggressive campaign of purification and transformation. To find that many yonis at the comparatively small (by Borobudur or Prambanan standards) temple complex means that the approach taken at the site was mechanistic—one imagines an assembly line of yonis and files of practitioners (believed to be hermits and ascetics) bathing in the sacred, life-giving water. This does not represent devotion in any generally accepted sense of the term, but rather direct manipulation of the system and its tools—in other words, a Tantric approach to spirituality.

This becomes clearer as we examine more closely the iconography at Sukuh and realize the extent to which Bhima, among others, has become “tantricized” and been enlisted in the process of spiritual transformation—a process that involved not only being “tantricized,” but also “Javanized.” The result is a form of Tantra that can be considered unique, yet just as efficacious as its Indian original.

The Bhima Cult and Ritual Purity Anyone who studies Indian religion comes to the realization that there are as many forms of that religion as there are villages and towns in India. Some worship Shiva as the ultimate god; for others, it may be Brahma or Vishnu. On a local level, different regions have loyalties to different gods and goddesses. Some worship Kali or Durga. Others worship Krishna, or Ganesha, or Uma, or Parvati. Some Tantric sects are considered Shakti denominations, for they believe that the Mother Goddess is supreme; others, of course, are Shiva circles. The varieties are endless, but, in the final analysis, all are manifestations of an overall belief system that we call Hinduism for the sake of convenience, for they have more relationship to each other than to anything outside of Indian culture.

This malleable quality of Indian religion lends itself well to regional differences abroad, as well. In Indonesia, the forms that were adopted early in its history were more or less normative. The architecture of Borobudur and Prambanan is evidence of a careful emulation of its Indian source—in their layout, in their adherence to the requirements of Vastu, in the iconographic designs of Buddhas, gods, and goddesses, and even in the lingga-yoni structures. Centuries later, however, all of this changes.

The temples at Candi Ceto and Candi Sukuh represent a significant departure from Indian norms. The Majapahit dynasty was under enormous pressure from within and without. Islam was dominating the archipelago from its outposts along the coasts and the trading centers, moving slowly inland and converting Javanese to its faith. Added to this was an internecine political situation of nearly Byzantine proportions. As Islam moved into Central and East Java, the Majapahit rulers moved farther and farther east, up into the mountains where they established their cult centers. At this point, either due to lack of time or funding, or to a general desire to reconnect with their cultural roots in the face of the “alien” faith of Islam, they abandoned traditional Indian architecture.

These two temples in particular are built in a terrace style, layered up the side of the mountain. Rather than having a central shrine or temple that is in the center of a square or rectangular plaza, the main temples at each site are approached from one direction only, terrace by terrace. There has been much speculation as to the purpose behind the design. Why is the main temple in the form of a truncated pyramid? Or is the appearance of the temples more the result of bad or incomplete restoration work than deliberate design? In the next chapter, we will look at another such terrace-style temple complex, but for now, what draws us more deeply into Candi Sukuh is the proliferation of symbols that demand closer inspection.

Bhima is one of the central personalities of the Mahabharata. This epic tale is the story of a war between two families, the Pandawas or Pandavas, and the Kauravas. Bhima, a member of the Pandawas, is well-known for his military prowess and incredible physical strength. He is the son of the Lord of the Wind and Air, Vayu, and brother to Hanuman, the trickster and monkey god who is the loyal friend of Rama and Sita. (Vayu is also known as the first of the gods to taste the amrita when it was produced by the Churning of the Milk Ocean.) Esoterically, Bhima is associated with the “ether,” the source of existence and “fulfiller of desires of all living or lifeless beings,” according to the Linga Purana.22 This is consistent with his lineage from Vayu, the Lord of the Wind and Air.

Bhima's attraction for the Majapahit rulers was probably his role as the fabled military commander in the Mahabharata. Some of the reliefs at Candi Sukuh show Bhima defeating his enemies. The panel on page 169 depicts Bhima in the center—recognizable by his curled hair—lifting an enemy into the air with one hand.23 The enemy figure is usually described as the giant Kalantaka (a form of Yama, the God of Death) or his twin, Kalanjaya, both of whom have been cursed by Shiva to live in a cemetery as servants of Durga.24 This may be part of the Sudamala story (see below), or it may represent the search of Bhima for amrita and his war against the God of Death, who must be defeated before the amrita is secured.

Political legitimacy was as much a requirement for the Javanese rulers as military superiority, however, and legitimacy was bestowed by the identification of the political rulers with spiritual forces. Thus, Bhima had two functions for the state: military strength and invincibility, plus his role as the provider of amrita. The supply of this elixir vitae was seen as evidence of both the supernatural power of the rulers and the favor of the gods. It was also essential to the rites of purification that were undertaken by the Tantric ascetics at Sukuh. Purity was at the heart of the process of spiritual transformation, just as it is in chemical transformation. Impurities can hinder or even derail the process at the very outset, so steps must be taken to remove those impurities before the process begins and all during the course of the process itself.

Purity may be understood in two ways: as ritual purity, which comes from strict adherence to laws concerning mostly biological functions (eating, drinking, sex, menstruation), and as moral purity, which is more difficult to establish on an individual basis. Often, moral purity was understood to be a reflection of ritual purity: if one followed all of the rituals laws, it was assumed one was in a pure state.

Ideas of purity and tabu preoccupied social anthropologist Mary Douglas, who saw in these rituals an attempt to impose order on chaos. She also understood that there are political implications where purity and tabu are concerned, and that “bodily orifices seem to represent points of entry or exit to social units, or bodily perfection can symbolize an ideal theocracy.”25

Purity, especially of water, was an obsession among the ancient Jewish Qumran community as well. Discovered by accident in 1947, the Dead Sea Scrolls tell us of a group of men and women for whom purity was so important that they believed prospective members of the community would pollute their water supply merely by drinking from it. They thus imposed a two-year probationary period on new initiates before they were allowed to drink from the community's water.26 They also believed that if pure water was poured into an impure vessel, the entire pitcher of pure water became polluted (as if the impurity of the vessel could travel up the stream of water into the pitcher).27 These two ideas—of new initiates being forbidden to drink pure water, and of impure vessels polluting pure water—are obviously related. A prospective initiate is an impure vessel, and is in danger of polluting the entire community. When Mary Douglas was writing her seminal work, Purity and Danger, there was not much known about the Qumran community, as the bulk of the Dead Sea Scrolls had not yet been translated and published. Her observations about purity in Indian religion are thus restricted to Brahmanism and do not include antinomian Tantric practices, yet her insight concerning the importance of purity and tabu in ordering society is relevant to our study nonetheless:

... if uncleanness is matter out of place, we must approach it through order. Uncleanness or dirt is that which must not be included if a pattern is to be maintained. ... It involves us in no clear-cut distinction between sacred and secular. The same principle applies throughout. Furthermore, it involves no special distinction between primitives and moderns: we are all subject to the same rules. But in the primitive culture the rule of patterning works with greater force and more total comprehensiveness. With the moderns it applies to disjointed, separate areas of existence.28

Douglas’ “rule of patterning” can certainly be applied to any study of the temples on Mount Lawu. “Matter out of place” can apply, not only to ordinary ideas of dirt and pollution, but also to threats to society coming from outside the body politic. In this case, the “matter out of place” can be construed as the threat to the Majapahit dynasty coming from Islam. The multiplication of yonis at the site of Candi Sukuh seems to imply a greater insistence on ritual purity, which may be a reaction to the perceived threat. The elevation of Bhima to the status of a cult totem may be another reaction: strength and military might as a deterrent to the forces massing against them.

The third component is the proliferation of phallic symbols throughout the site and the reliefs depicting military conquest on one hand and the elixir of immortality on the other. As Douglas observes, “there is no clear-cut distinction between sacred and secular.” The state and the cult were one and the same. The monarch was the earthly representative—if not the actual incarnation—of a god. In the Islamic context, this would be the height of blasphemy. In that context, there would be no place for Tantric kings. It was not only one monarch's political sovereignty that was in peril; it was the overall “pattern” itself. The entire social structure was in jeopardy—not only the Majapahit dynasty or any one monarch of it, but the entire Hindu-Javanist worldview. Monotheism would replace polytheism; Islamic art with its abhorrence of icons and statues would replace Hindu art with its celebration of sensuality and voluptuousness, of divine, human, and animal forms. The arcane Javanese language of ritual would be replaced by Arabic—the Mahabharata and Ramayana by the Quran.

Drastic measures were required, and these measures help us to understand how Tantric ideas of sexuality were promoted and practiced in 15th-century Java. The cult of Bhima is one way the last pre-Islamic rulers of Java sought to consolidate and reinforce their power.

At the time of the temple's construction, there was a struggle for power going on between two Majapahit leaders. One was a queen, Suhita, who was bending to the pressure of both the Islamic forces encroaching on Java and the Chinese envoys who were jockeying for position at the court. The ascendancy of these foreign influences was threatening a permanent dislocation of the Javanese nobility, causing some of them to rally around a rebel commander, Bhre (“prince,” sometimes translated as “duke”) Daha.29 Bhre Daha successfully overthrew the Queen, but was himself overthrown shortly thereafter. He fled to the mountains east of Yogyakarta and declared his independence sometime around 1437 CE, consecrating a royal lingga at Candi Sukuh in 1470 CE.

This political situation was interpreted in the context of Javanese religion. The Queen of Majapahit was identified with Durga, in this case a form of Durga that inhabits cemeteries. As we discussed above, this narrative belongs to the Sudamala story in which Uma is cursed by Shiva. The reason for the curse is interpreted variously, depending on the text involved (whether normative Hindu texts like the Mahabharata, or a Javanized form like the Kakawin Ramayana, or others). In one version, already mentioned, Shiva wanted to have sex with Uma at a time she deemed inappropriate; in another version, Uma had illicit intercourse with Brahma, which incurred Shiva's wrath. Regardless, the reason for the curse had to do with sex and, moreover, inappropriate or illicit sex.

Uma is cursed for a period of twelve years. She must spend the time as Durga, haunting a frightening graveyard, until her sentence is over or until she has been freed by Sadewa. Her companions are ghosts and other creatures of the night. The implication is that Queen Suhita is Durga, the evil goddess, who must be overthrown by the heroic Pandawa brothers. Bhima is one of those five brothers. In the relief shown opposite above at Candi Sukuh, he is shown with Semar, the quintessential Javanese god, banging a gong and preparing for war.

In the next photograph, opposite below, we see the story of the Evil Queen—in this case, Durga. She is in the cemetery of the gods, standing in the center of the relief and surrounded by ghostly emblems. In front of her, tied to a tree, is Sadewa, who alone has the power to free her from the cemetery. Durga is threatening to kill him with her sword unless he relents and releases the curse that Shiva has put upon her. In front of her is a bodiless head reminiscent of Rahu, but perhaps intended to be a ghostly figure. There are other weird creatures behind the tree to which Sadewa is tied.

Behind Durga are two of her female servants, one of whom possibly represents Kalika (her demonic servitor). The hanging, pendulous breasts are usually signs that the women being depicted are evil, sometimes witches. For comparison, see the example on page 175 from Prambanan, where an evil goddess or witch is suckling two imps on her rather tubular breasts.

The only way Sadewa can lift the curse from Durga is if his own mother, Kunti, asks him to do so. Kalika, the female servant of Durga, demonically possesses Kunti, who then demands that Sadewa lift the curse. Reluctantly, mother and son return to the cemetery, but Kalika leaves the body of Kunti too early and the ruse is revealed. Mother and son then return home, but Kalika once again possesses Kunti.

To make a rather long and intricate story a bit shorter, Sadewa finally does lift the curse from Durga, who then turns back into the beautiful Uma. Shiva blesses Sadewa and gives him the name by which this story is known, Sudamala (“one who cures sickness”). Further along in the story, Sudamala cures a hermit sage of his blindness and is rewarded with a wife.

Many elements of this story could have been applied easily to the political situation at the time, even going so far as to legitimize the reign of Bhre Daha. Queen Suhita is, of course, Uma-become-Durga. Bhre Daha is himself Sudamala, or perhaps Bhima. The nobles who stayed with Queen Suhita can be portrayed as having been possessed by Kalika, and so on. In a sense, it is a blameless way of presenting political events: the Queen has been cursed; her supporters are possessed by demons; all will come right in the end if Bhre Daha remains steadfast and lifts the curse from the Queen so that she comes to her senses. Perhaps Queen Suhita was “cursed” for the same reason Uma was cursed by Shiva: for whoring after the foreign elements, the Chinese and the Muslims.

The warlike atmosphere represented by some of the reliefs at Candi Sukuh certainly seems to reflect a preoccupation with armed conflict. The relief on pages 176 and 177 is controversial, and scholars disagree on what exactly is being represented, since the figures seem anomalous for a temple. There is some agreement that there is a panel missing between the left panel and the center. Nevertheless, what we have is certainly suggestive for anyone who has studied the works of Eliade concerning alchemy.30 The general impression is of an iron worker (left panel) who is engaged in making weapons of war, among them the famous kris—a weapon believed to have mystical properties. At the far right is a figure of a person working the bellows that keep the fire burning hot. What seems totally out of place is the rather strange dancing elephant and dog in the center panel.

A closer look allows us to see the weapons being made more clearly, just to the right of the iron worker's head. They are obviously swords and axes used in battle, minus their wooden hilts. Above the figures of the swords are enigmatic symbols that some observers claim are mystical signs associated with the creation of weapons.

Looking yet more closely, in the photo on page 177, we can see that those symbols are tridents (usually associated with Shiva), a sword shape, an hourglass type figure, and several serpentine forms. The author has yet to see a convincing identification of these figures.

As reference to Eliade's work suggests, the presence of these reliefs at a Tantric temple may not be as out of place as it seems:

In our view, one of the principle sources of alchemy is to be sought in those conceptions dealing with the Earth-Mother, with ores and metals, and, above all, with the experience of primitive man engaged in mining, fusion and smithcraft. ... Now these techniques were at the same time mysteries, for, on the one hand, they implied the sacredness of the cosmos and, on the other, were transmitted by initiation ... mining and metallurgy put primitive man into a universe steeped in sacredness.31

Eliade identifies alchemy and alchemical processes with ceremonial initiation, as well as with psycho-biological processes, and rightly understands that Indian alchemy and Tantra are linked.32 By completing the circle with metallurgy and smithcraft, Eliade has given us a tool for understanding the role that this relief plays in such an erotically charged Tantric temple as Candi Sukuh. The German Tibetologist Siegbert Hummel goes even further when he demonstrates that the blacksmith represents fertility and shamanic initiation in Tibet, a country with close ties to Java, as we have seen.33

We can as easily identify the figure at the far right of the relief as operating a churn as a bellows, and it was the churning of the ocean that gave us the water of life, the sacred amrita. The iron worker on the left panel is transforming the raw material of the earth into items sacred to Shiva, a process analogous to human procreation. The kris—the long knife (or short sword) familiar to anyone who has spent time in the region—has long been understood to represent Shiva and the vital life force. The mysticism surrounding this iconic Indonesian and Malaysian weapon is profound and extensive. Even such a well-known personality as Gerald Gardner (1884–1964), founder of the modern Wicca or Witchcraft movement that bears his name, wrote a monograph on the kris during his sojourn in the archipelago that is still reprinted today in studies of this enigmatic device.34

To Indonesians or Malaysians, the kris (sometimes spelled keris or kriss) is equivalent to the Arthurian Excalibur. The knife often (but not always) has a wavy, serpentine blade that is immediately recognizable. A kris must be made by a qualified craftsman who is also part shaman. It is a sacred duty, to be begun on propitious days and tied to the personality of its owner; the knife itself is believed to embody the maker's soul or spirit, his shakti. Like Excalibur, it is a personal weapon; not everyone can lift the sword from the stone. No one should touch or use another's kris, except under particular circumstances. They are worn by sultans and (male) members of noble households on ceremonial occasions. They can be very simple, or as ornate as possible, their scabbards studded with precious gems and cased in gold and silver.

That the kris has peculiar characteristics is something to which the author can readily attest. Once, in the city of Melaka in Malaysia, he was browsing through a small curio shop crowded with the usual odds and ends, souvenirs, and bric-a-brac. On one shelf, behind rows of tiny figurines and other precariously arranged merchandise, was a simple wooden kris. He noticed it, but did not retrieve it for a closer look (worried as he was that he would knock down an intervening row of delicate clay figurines in the process). Instead, as he made to leave the aisle, the kris “fell” off the shelf and landed on the floor directly in front of him.

The sheer impossibility of this was astonishing. None of the merchandise that blocked the knife had moved or been disturbed in any way. It was as if the kris had flown over them from the back of the shelf and through the very narrow space between the figurines and the next shelf above them. (For what it's worth, this took place on October 31. Halloween, however, is not a holiday celebrated in that predominantly Muslim country.) Of course, the author felt compelled to purchase the kris, which is shown in the photo on page 180.

The panel in the controversial relief shown above that contains the elephant and the dog has given rise to all sorts of speculation. The author believes it refers to one of the stories in the Jataka—the tales of the previous incarnations of the Buddha, some of which are depicted on the panels at Borobudur. In this case, the Jataka in question is the Abhinha Jataka, which is quite short.35 In the story, a dog befriends an elephant. The dog eats whatever falls from the elephant's mouth and grows fat in the process. Gradually, the elephant becomes aware of the dog and they develop a close friendship. It should be noted that this is no ordinary elephant, but the elephant of state—a member of the royal retinue.

One day, however, the mahout (the man in charge of the elephant) sells the dog. The elephant falls into a deep depression, and no one knows why. Finally, a wise man discovers the truth and asks the king to demand that the dog be returned, or else a penalty will be imposed on the owner. This is done, and the dog and the elephant live happily ever after.

According to this Jataka, the dog was a lay disciple of the Master (the Buddha). The elephant was an aged Elder, and the wise man was the Buddha himself. This story was told as an illustration of reincarnation, for the frame of the tale concerns several monks remarking on how close a lay disciple and an Elder are and wondering at its meaning. The Buddha tells them that they knew each other in a previous life, as a dog and an elephant.

What relevance does this episode—from an anomalous Buddhist and not a Hindu or Javanese source—have for Candi Sukuh? Is it another allegory of the political situation? Since we seem to be missing at least one of the relevant panels, we may never get to the bottom of this mystery. Is it possible that the elephant represents the Majapahit kingdom, and the dog represents the kingdom's subjects, who have been “bought” by the evil Queen Suhita? Does the restoration of the dynasty by force—the iron worker making an arsenal of weapons—represent the king demanding the return of the dog, under dire penalty?

Realizing that Candi Sukuh is a temple, and a Tantric one at that, it is necessary to look a level or two deeper. We have seen that the panels showing the manufacture of weapons at an ironsmith's anvil is a metaphor for the alchemical—i.e., Tantric—process. The other erotically charged emblems at the site reinforce the idea that this was not the place to make a naked political statement, but a machine in stone for effecting cosmic change and transmutation. A necessary quality of the “twilight language” is that it can refer to multiple layers of meaning simultaneously. A political illustration is also an alchemical figure, is also a Tantric yantra or mandala, is also a spiritual truth.

The Bird-Men of Candi Sukuh The stonework at Sukuh is awash in references to amrita, to the transformation of gods into demons and back again, and surprisingly to the practice of Kundalini yoga, the art of transforming physical energy into spiritual force. Let us look at some of these examples before we come to any conclusions.

First, let us examine the “bird-men,” which some assume to represent Garuda. These figures—most of them missing their heads and thus causing more difficulty in identification—are usually associated with the gathering of amrita from the Nagas, or serpents. They seem strangely humanoid, unlike the usual depictions of Garuda. In some cases, they are shown standing on serpents, which is a direct reference to the story of Garuda and his seizure of the amrita from the Nagas. Some have talons; others, like the one on page 182, seem to have human feet and hands, although they all have wings.

The relief opposite shows Garuda holding an elephant and a turtle in his talons, a reference to the tale of Garuda in the Mahabharata that occurs immediately before he is sent to retrieve the amrita from the Nagas, the serpent gods.

The photo opposite and the two photos below clearly show the Nagas at the base of one of the reliefs and one at the entrance to the complex, thus reinforcing the idea that at least some of these bird-men are Garuda and that the theme of the statuary is amrita.

Now let us look at the massive stone turtles that are one of Sukuh's most impressive features. The next three images show stylized turtles at the base of the temple entrance. The last shows, in a close-up, sticks of incense inserted in the ground next to the turtle.

The turtle has a special significance, of course. It was on the back of the turtle that the Churning of the Milk Ocean took place, so their appearance at Sukuh only serves to reinforce the idea that the purpose of the temple was the collection of amrita. Many authorities believe that these statues served some function as offering tables or altars. Another scholar, however, has offered a different interpretation of the turtles at Sukuh and it is worth considering.

Victor M. Fic was a Czech student at the end of World War II who escaped to Canada at the time of the Communist takeover, after having been arrested and sent to prison. He became involved in Asian studies and, in the 1960s, was executive secretary of the Institute of Southeast Asia at the prestigious Nanyang University in Singapore. Fic has written extensively on Communism and Eastern European politics on the one hand, and on Asian religion, culture, and politics on the other. His special interest seems to be Indonesia, and he has published several books on that country. In one of these, he makes the startling claim that the turtles of Candi Sukuh represent nothing less than an esoteric maneuver from Tantra yoga known as the vajroli mudra.36

According to the Shiva Samhita—a core text of Hatha yoga that has influenced generations of scholars and practitioners alike—the vajroli mudra is “the secret of all secrets, the destroyer of the darkness of samsara.”37 The term vajroli comes from the word vajra, or “thunderbolt” (in Tibetan, dorje). In order to prevent the loss of psycho-spiritual energy, yogins attempt to restrict the flow of semen during sex using various methods. Some of these permit orgasm but restrict ejaculation, instead diverting the ejaculate back into the body using one of two methods. The first, called sahajoli mudra, involves blocking the urethra in such a way that the seminal fluid flows into the bladder, from where the grosser physical elements are eventually expelled, but not the rarer, spiritualized elements. The second, known as amaroli mudra, uses the penis as a kind of vacuum cleaner to draw the ejaculated semen as well as any fluid discharge of the female partner—a mixture of male and female fluids known as the amrita—back into the male body. These methods are subsumed under the rubric of vajroli mudra, the “thunderbolt” mudra.

In both cases, yogins train by exercising various muscle groups, contracting the urethral muscles used to restrict the flow of urine (for example), or, in the case of yoginis (female practitioners of yoga), the vaginal muscles. The idea is to retain the energy that would otherwise be dissipated in the sexual act and redirect it upward along the nadis or etheric nerve channels in the body, activating the chakras along the way until the sacred marriage of Shakti (the energy) and Shiva (consciousness) takes place in the chakra in the brain, behind the eyes.

The relationship of the turtle to this process becomes clear if we think of how the turtle withdraws into its shell. This retraction mimics the retraction of the urethral or vaginal muscles during the vajroli mudra. Understanding that this mudra is the “secret of all secrets” and is at the very heart, not only of Hatha yoga, but of Kundalini yoga and Tantra, we can appreciate the importance of Candi Sukuh as a temple designed specifically to train its devotees in the most powerful of all Asian esoteric practices. This mudra is designed specifically to collect amrita—the commingled male and female essences that together guarantee immortality and liberation. It is represented in a temple complex surrounded by symbols of amrita and transformation. Should the temple ever be completely restored to its original design—complete with the many yonis and lingga—the overall effect would be deeply profound, for it would become obvious that Candi Sukuh was much more than a mysterious pile of rocks and stones, but was as important in its day as Chartres Cathedral was in France. They were both designed as a book of instruction, as well as engines of alchemical transformation. Although both monuments refer to the same process, they use different forms of the twilight language to do so. In the case of the Gothic cathedrals, the form the language takes is Biblical; in Candi Sukuh, the references are to Hindu-Javanese religion and scripture. The differences may reflect cultural distinctions and not a different process entirely.

At Sukuh, we find the fascinating relief on page 190, showing a personage holding two thunderbolts. Depictions of stylized thunderbolts, known as vajra or dorje, are rather rare in Javanese temples, so this one commands a great deal of interest, aside from its vaguely Central American appearance (another reason many visitors are reminded of Mayan temples when they see Candi Sukuh). Whether this figure is a king or a god is difficult to tell. He is standing on what seems to be a crescent moon, and is wearing a crown, reminding us of the famous Burney relief (shown on the opposite page), now at the British Museum, of a Mesopotamian goddess (Ishtar, or Ereshkigal?) or the demoness Lilittu (the original “Lilith”). In the Burney relief, the winged figure is depicted holding the “rod-and-ring” insignia in her two hands. This is believed to represent a measuring cord and rod, implements that the Sumerian goddess Inanna took with her during her descent into the Underworld. They were also given to the god Marduk—who defeated the dread monster Tiamat—as symbols of his authority and as weapons.

With her wings and taloned feet, the figure in the Burney relief easily could be the female version of the Garuda statues at Candi Sukuh. In fact, in one episode in the life of Garuda, he lifts an elephant and a turtle with his talons in order to devour them. As we have seen above, there is a relief at Sukuh that depicts this episode, and the iconography is reminiscent of the goddess in the Burney relief with her talons on the twin lions. There is even a similarity in the headdresses of the two.

The author is not suggesting there is a direct link between these two figures, but rather that the idea of half-human, half-birdlike creatures that descend into the Underworld to steal the secrets of immortality is a meme that deserves greater investigation than can be accomplished here. Either the two cultures—Mesopotamia and India—developed the same concept independently, or there was actual contact between the two at some remote period in history, either directly or through an intermediary culture. If the former, then the concept may reflect some common experience rooted in agricultural beliefs and practices of a chthonic (and perhaps lunar) nature.

Some of the other figures are more clearly phallic in nature, as the reliefs shown on pages 192 and 193 demonstrate. The photograph on page 192 shows a figure that is probably only partially restored. While the penis is not erect, it nevertheless shows the presence of the palang insertions discussed earlier. On page 193, we see a relief showing an ithyphallic creature holding two instruments. The one in his right hand seems to be a horn, but the one in his left hand is unidentified. The creature's open mouth may serve a functional purpose, for the dispensing of holy water or simply for drainage. Its posture calls to mind the ganas of Shiva that are found at Prambanan.

Then there is the famous statue of a headless man grasping his penis shown opposite. While the palang insertions can be seen just below the glans, what is not evident is any sign of other ornamentation or any means of identifying who this is supposed to be. The figure's stocky quality may lead us to believe that this is Bhima, and there is something on his right hand that adds some credence to this.

One of Bhima's characteristics is a long, curving thumbnail on his right hand. This is said to be his most important weapon, and it can be seen on a relief showing him lifting Kalantaka, one of the giants of the Underworld. There is some similarity between that depiction and this one, so it may be purely speculation at this point, but it is probably safe to say that this relatively unadorned statue represents Bhima. From the presence of incense sticks in front of the statue, we realize that the local Hindu population reverences this figure as much as any other in the Sukuh pantheon. Its placement is also significant—next to what appears to be a Bhima shrine, as shown in the photograph at the top of page 196. On either side of the shrine are figures in relief that appear to be standing on pedestals, with supplicants standing or kneeling before them. This is an image we will come across later.

Another side of the same shrine shows rows of figures, including some monstrous entities on the lower panel, one of whom displays a phallus with the palang inserts (see bottom photo on page 196).

Perhaps the simplest expression of the phallo-centric nature of Candi Sukuh, however, is the standing stone shown on page 197. It is possible that this stone predates the construction of Candi Sukuh, and that may be one of the reasons why Mount Lawu and this site in particular was chosen for the temple. Mount Lawu was said to be sacred before Sukuh was erected, and was a place where ascetics came to pray and meditate.

There is something carved at the top and side of the phallic stone, but the degree of weathering and erosion is so great that identification is difficult. One can hazard a guess, however, that it represents an animal of some sort, perhaps a serpent or something with a long hanging tail.

Phallic statues—although they are the features that usually dominate any discussion of Candi Sukuh—are only one aspect of the site, however. We have seen the multiple Garudas with their Nagas, and the giant turtle sculptures that may or may not represent the vajroli mudra; we have seen the forge where the ore from the earth is refined into sacred objects and the mysterious dancing elephant with his pet dog. We have also gazed at the reliefs that tell the Sudamala story, with their Durga and Bhima, their Semar and Kalantaka. But there is one final relief that demands our attention and it, too, is as mysterious as the rest of the complex. It is replete with symbolism and open to a variety of interpretations.

It is a large panel, shown opposite, ovoid in shape, suggesting the Greek letter omega. The shape is defined by the tails of two birds that meet at the top, where a wrathful Kala figure is seen as if it were guarding the entrance to a temple. Within the omega are two figures, standing on a serpent with two heads. One of the figures is on a pedestal, which implies divine status. The other figure is human and may represent Bhima. The divine figure is offering something to the human figure—and there has been some speculation that what is being offered is a flask containing the amrita whose collection is at the heart of the entire temple complex.

Once again, we are faced with an artistic expression that is unique in Java. This is not the standard Indian-inspired iconography of the other temples we have discussed so far. And, although the figures bear resemblance to the wayangstyle designs of the Sudamala reliefs, the overall composition of the panel is quite strange. Due to the restoration work on the site that has been proceeding on and off for decades, we cannot say for certain that the panel is even in its original location. Its association with Bhima and the symbols of birds and serpents, however, seem to emphasize its relation to the amrita theme.