THE TIBETAN AVALOKITEŚVARA CULT IN THE TENTH CENTURY: EVIDENCE FROM THE DUNHUANG MANUSCRIPTS

THE TIBETAN AVALOKITEŚVARA CULT IN THE TENTH CENTURY: EVIDENCE FROM THE DUNHUANG MANUSCRIPTS

SAM VAN SCHAIK (LONDON, ENGLAND)

I. INTRODUCTION

As most readers will know, all the manuscripts from the library cave at Dunhuang date from before the eleventh century of the common era. Most of the Tibetan manuscripts were carried away by Paul Pelliot and Aurel Stein on behalf of France

and Britain, and now reside in the national libraries of these two countries. Neither the French nor the English collection was ever fully catalogued. This has led to a situation where work on individual texts has not generally been complemented by an overall view of the

manuscript collections in which those texts are situated, a situation which has only recently begun to change in studies of the secular documents, especially in the work of Tsuguhito Takeuchi. The Buddhist manuscripts have so far not been the subject of a comprehensive overview of this

kind. Due to the extent and diversity of the Buddhist manuscripts, such an undertaking would indeed be considerably more difficult than for the secular material.

As well as becoming more comprehensive, work on the Dunhuang texts has just begun to be more integrated with the a study of all physical features of a manuscript, including the script and handwriting (palæography), and the form of the manuscript (codicology). There has also been an increasing recognition that textual work should not be carried out in isolation from work on the pictorial representations found in the Dunhuang library cave material and in wall paintings.

This paper results from an attempt to apply this more comprehensive approach to a self-contained research project on a thematically-linked group of manuscripts: the Tibetan Dunhuang texts of the deity Avalokiteśvara (Tib. Spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug). I will try to demonstrate here that a comprehensive approach to the Dunhuang manuscript collections can lead to conclusions rather different from those derived from work on only a few specific manuscripts.

In the 1970s some important Tibetan Dunhuang texts on after-death states featuring Avalokiteśvara were discussed by Rolf Stein and Ariane Macdonald. The first of these texts, Showing the path to the land of the gods (Lha yul du lam bstan pa) describes the various paths which the deceased might take, and exhorted the deceased to remember the name of Avalokiteśvara and to call upon him in order to avoid the hells. The second text was identified by Stein as a funeral rite of the pre-Buddhist Tibetan religion transformed into a Buddhist practice featuring Avalokiteśvara.

A compendium of short texts also concerned with death and the after-death state was examined by Yoshiro Imaeda. One of these, called Overcoming the three poisons (Gdug gsum ’dul ba), contained Avalokiteśvara’s six-syllable mantra. Like the text studied by Stein, this one seemed to be addressed to an audience familiar with pre Buddhist rituals. Imaeda pointed out that this was the only example of the six-syllable mantra found in the Pelliot collection, and suggested that the role of Avalokiteśvara in ancient Tibet might be much less significant than the later tradition tells us. His work, along with Macdonald’s examination of ancient material related to King Srong btsan sgam po, challenges the traditional accounts of the significance of Avalokiteśvara in the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet. Based on these studies, Matthew Kapstein has argued in his recent book The Tibetan Assimilation of Buddhism that the Tibetan cult of Avalokiteśvara is primarily a product of the period of the later spread of the teachings, that is, from the eleventh century onwards.

II. THE DUNHUANG AVALOKITEŚVARA TEXTS

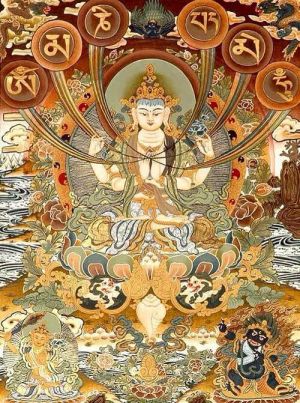

In the course of my work on the Dunhuang collection at the British Library, I began to realise that these texts on the post-death state represented only a fraction of the Avalokiteśvara material. Most of the familiar forms of Avalokiteśvara are represented in the Dunhuang manuscripts. The simplest aspect of the deity has one face and two arms. We also find the form with eleven heads called Ekādaśa-mukha (Tib. Zhal bcu gcig pa). There is the form with a thousand arms and a thousand eyes, Sahasrabhuja-sahasranetra (Tib. Phyag stong spyan stong dang ldan pa). We have Avalokiteśvara holding a wish-fulfilling jewel and a wheel, known as Cintāmamicakra (Tib. Yid bzhin ’khor lo). Finally, there is Avalokiteśvara in the form known as “the unfailing noose,” Amoghapāśa (Tib. Don yod zhags pa), a very popular form in Dunhuang. All of these aspects of Avalokiteśvara are usually white in colour, but he is also represented with a red, a blue and a golden body.

The texts I will look at here are those in which the role of Avalokiteśvara is absolutely central, leaving aside those in which he appears along with other bodhisattvas like Mañjuśrī. The texts so devoted to Avalokiteśvara are overwhelmingly tantric in nature. Leaving aside the funerary texts, which have been discussed in detail in the sources mentioned above, there are four basic categories of Avalokiteśvara text from Dunhuang:

1. Sūtra

2. Dhāranī

3. Stotra (hymns of praise)

4. Sādhana (the visualisation and recitation practice of the deity) In the first category, sūtras, there is only one text, found in two manuscripts. This is the Avalokiteśvara chapter of the Saddharmapundarīka sūtra (The Lotus Sutra), which describes the forms taken by the bodhisattva in order to save sentient beings. This chapter, known as The Universal Gateway (kun nas sgo, Ch. pumen), was particularly popular in China, where it took on the form of an independent text from the seventh century onwards. There are dozens of Chinese manuscript copies of The Universal Gateway in the Dunhuang collections. This Tibetan version seems to have been extracted from the eighth-century translation by Snanam Ye shes sde, which is also the canonical version. We know that the Saddharmapundarīka was translated into Tibetan in the eighth century, as it appears in the ninth-century catalogue of Tibetan translations, the Ldan dkar ma.

The other major sūtric source for the cult of Avalokiteśvara found in the Ldan dkar ma is the Kāranavyūha sūtra. This late sūtra displays several features found in tantric literature, including a mantra (the six syllable mantra itself) and a ma&'ala. In the sūtra, Avalokiteśvara has the role of a universal saviour. There is no Tibetan translation of the Kāranavyūha in the Dunhuang collections, but the sūtra does seem to have influenced the two previously-mentioned texts on the after-death state, Gdug gsum ’dul ba (with the inclusion of the six-syllable mantra) and the funerary rites that appear in PT239 (wherein Avalokiteśvara appears in the form of the white horse Bālāha).

In short, the extent of the sūtric material devoted to Avalokiteśvara is quite limited. When we move on to the dhāranī-s, there is a great deal more material. A dhāranī (Tib. gzungs) is a sequence of Sanskrit syllables used to attain a variety of worldly and transcendent goals.13 The texts which expound a dhāranī are usually (and somewhat confusingly) also termed dhāranī or dhāranī-sūtra. A dhāranī text, as well as explaining the uses of the deity’s dhāranī, may also contain instructions for creating the altar and physical representations of the deity.

I have identified twenty manuscripts containing at least seven different dhāranī texts dedicated to Avalokiteśvara. Different texts are dedicated to the eleven-headed form, the thousand-armed form, and the Amoghapāśa form. Several of these texts appear in the Bka’ ’gyur, mostly in versions very similar to the Dunhuang texts. The dhāranī-s are mostly variations on a single theme, beginning, Āryāvalokiteśvarāya Bodhisattvāya Mahāsattvāya Mahākarunikāya. The dhāranī of the thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara also addresses the deity as a siddha-vidyādhara, an accomplished esoteric adept.

The next category of texts is the hymns of praise, or stotra (Tib. bstod pa). There are two such texts addressed to Avalokiteśvara, which appear in twenty-one manuscripts. The first text is a hymn to the deity in the six-armed form of Cintāmanicakra. Avalokiteśvara is addressed in the terms of a tantric deity, and his ma&'ala is taken as an embodiment of the mind’s true nature:

If you meditate on this ma&'ala of mind itself, The equality of all ma&'alas, Conceptual signs will not develop.

Conceptualisation is itself enlightenment.

With this non-abiding wisdom

All accomplishments will be perfected. I have identified five manuscript copies o f this text, which was apparently quite popular. It does not, however, appear in the Bka’ ’gyur or Bstan ’gyur. The other hymn is an enumeration of the 108 epithets of

Avalokiteśvara. This text does appear, in a nearly identical form, in the Bka’ ’gyur. In this text Avalokiteśvara has four arms, holding a lotus, a vase, a staff and a rosary. At the end of the text it is written that the benefits of praising Avalokiteśvara with these epithets include the entry into all ma&'alas and the accomplishment of all mantras. The 108 epithets of Avalokiteśvara is the single most common Tibetan Avalokiteśvara text in the Dunhuang collections, appearing in at least fifteen manuscript copies.

The last category of Avalokiteśvara text is the sādhanas. There are only a few manuscripts containing sādhanas, but we are fortunate in that they represent a wide range of sādhana forms. At one end of the spectrum, we have ritual manuals for the attainment of worldly aims through practices like fire rituals (homa)—the kind of text usually classified as kriyā or caryā tantra. One 28-folio booklet (ITJ401) contains several such ritual texts, which invoke Avalokiteśvara in his thousand armed form, or in the form of Amoghapāśa. Figures from the ma&'ala of Amoghapāśa, such as Hāyagrīva and the goddess Bh(ku)ī, also appear. There are a great variety of small sub-rituals included within the larger homa context. These address a great variety of worldly needs, a sample of which is provided by the following opening lines:

(i) “If you want to avoid being bitten by a dog”

(ii) “If you have cataracts”

(iii) “If you are afraid of the dark”

(iv) “If you want to make water flow uphill”

(v) “If you need to make it flow downhill again”

Also included in this collection are some longer rituals, one for mirror divination, and one for making rain. In one ritual, the six-syllable mantra makes another cryptic appearance in the form: O% vajra yak*a ma"i padme hū%.

I have also identified a sādhana of Avalokiteśvara in the Dunhuang manuscripts which would fall into the Yogatantra category. It appears in three versions, none of them quite complete. In two manuscripts, the sādhana opens with the identification of the practitioner of the sādhana as “one who desires the siddhi of Noble Avalokiteśvara in this very life”.20 In the sādhana, Avalokiteśvara is white in colour and has two arms, one in the gesture of giving refuge, and one holding a red lotus. He sits cross-legged on a lotus. To the left of him is the consort Dharmasattvī (chos kyi sems ma). The meditator is to develop the vajra pride in himself as *Bhagavān Śrī Dharmasattva (bcom ldan ’das dpal chos kyi sems pa) which seems to be another name for this form of Avalokiteśvara. In the Sarvatathāgatatattvasamgraha tantra, Avalokiteśvara belongs to the dharma family (which is identical with the padma family). The other deities of the ma&'ala are the standard eight offering goddess and four gate guardians of Yogatantra literature. There is a visualisation and recitation of “the root mantra of the heart mantra of approach”. The mantra is O% vajra dharma hrī. This mantra is based on the seed syllables of Avalokiteśvara according to the Vajradhātu ma&'ala of the Sarvatathāgatatattvasamgraha.

ITJ384 is a hastily written manuscript containing notes on various ma&'alas, includes an Amoghapāśa ma&'ala. This ma&'ala may also be tentatively classified as Yogatantra, as the other ma&'alas discussed in the same manuscript are all in some way related to the Sarvadurgatipariśodhana tantra. According to this text, the ma&'ala is laid out on the ground, with a vase at the centre representing Amoghapāśa. There seems to be some relationship with the ma&'ala diagram in the Dunhuang manuscript kept at the National Museum of New Delhi (Ch.00379), in which a vase is drawn in the centre of the ma&'ala for a healing ritual. There are a number of scriptural texts which may be sources for these Amoghapāśa practices, and there certainly does seem to have been an Amoghapāśa tantra in use by the eight century.

We have a single example of another type of sādhana which might be classified as Mahāyoga. The deity here is a red Avalokiteśvara, with one face and two arms, one holding the lotus and one giving refuge. Avalokiteśvara is visualised in union with the white-robed goddess Pā&'aravāsinī, surrounded by the deities Yamāntaka, Mahābala, Hayagrīva and Am(taku&'alī. These deities are generated out of “the bodhicitta arising from the great bliss of the father’s and mother’s nondual union”. This sādhana indicates that the popularity of Avalokiteśvara continued in the Mahāyoga practices which were prevalent in tenth-century Dunhuang. The form of Avalokiteśvara in this sādhana is similar to the form known as ’Jig rten mgon po or ’Jig rten dbang phyug (Skt. Lokeśvāra) in the later Tibetan tradition. I have not yet identified any sources for this Mahāyoga Avalokiteśvara practice, though it is possible that Tibetans were familiar in the tenth century with a Lokeśvaramāyājāla tantra.

III. OTHER APPROACHES TO THE MATERIAL

Having very briefly reviewed the range of the Tibetan Avalokiteśvara texts from Dunhuang, let us now look, equally briefly, at the physical form of the manuscripts in which these texts appear. There are four basic types:

1) The pothī: the loose-leaf form that became ubiquitous in Tibet;

2) The scroll;

3) The concertina; and 4) The booklet.

One interesting aspect of looking at the physical form of the manuscripts is that we can draw conclusions about the use to which the manuscript was put. The pothī is the most common form for Tibetan manuscripts from Dunhuang, followed by the scroll, then the concertina, and finally the booklet. Yet a large proportion of Avalokiteśvara texts are written on concertinas and booklets.

A feature of the concertinas and booklets is that they are often collections of several short prayers and sādhanas—an example is PT37, the collection of texts on the after-death state studied by Lalou and Imaeda. The concertina and booklet forms lend themselves to such collections because of the ease with which one can leaf through the pages to find a particular text. They are usually of a relatively small size, and thus easily carried on the person.

These collections of prayers and sādhanas may have been used by wandering monks or lay yogins either for personal use or when providing religious services for others. In post-imperial Tibet, such figures, who would have been literate in Buddhism but without monastic sponsorship, would probably have been common. It is easy to imagine most of the Avalokiteśvara texts in the Dunhuang collections being used in this way—texts to be read to the dying or deceased, rituals for healing the sick, helping crops, and sorting out personal problems, as well as general-purpose, all-accomplishing prayers like the 108-epithet prayer in praise of Avalokiteśvara.

The forms of the manuscripts can also be used to date them approximately. The concertina format was popular in China from the late Tang dynasty, that is the ninth century. The booklet, on the other hand, was not widely known in China until much later, and the Dunhuang booklets seem to date from the earliest experimentation with this form. The majority are dated to the tenth century.

We can also look at the handwriting of the manuscripts, although this approach to the study of the Dunhuang manuscripts is very much in its infancy. The palæographic features of our Avalokiteśvara manuscripts indicate that they did not originate from the scribal centre that operated in Dunhuang in the dynastic period. They are often characterised by rather ornamental flourishes, features which are predominantly found in the Tibetan script of the post-dynastic period, especially the tenth century. In this case the handwriting of the manuscripts would date them, rather roughly, to the period between the mid-ninth and early eleventh century, with the bulk of them being from the tenth century.

Other features of some manuscripts can help us to date them more accurately. For example, one of the hymns of praise to Avalokiteśvara is written on the verso of a scroll, the recto of which is a Chinese almanac written for the local ruler of Dunhuang, Cao Yuanzhong, concerning the year 956. We can see that the Tibetan side was written after the Chinese side, so the text must date from the half-century between 956 and the closing of the library cave in the early eleventh century. Two others of our Avalokiteśvara manuscripts may be linked with this scribe, and hence also placed in the second half of the tenth century.29 So many Tibetan texts from Dunhuang have now been found by this method of dating to derive from the late tenth century that the burden of proof would seem to rest on those who believe a Tibetan

Dunhuang manuscript to date from before the tenth century.

Finally, one indispensable source for establishing the presence o

f a text in early Tibet is the Ldan dkar ma, the catalogue of texts kept at the Ldan dkar palace written in the early ninth century (AD 814). The Ldan dkar ma contains the titles of some of our Dunhuang texts: the Saddharmapundarīka sūtra, the dhāranī-s of Amoghapāśa and the eleven-headed Avalokiteśvara, and the 108-epithet praise of Avalokiteśvara. The Kāranavyūha sūtra, which is not found in Dunhuang, but is the probable source of the six-syllable mantra, is also listed in the Ldan dkar ma.

IV. PICTORIAL REPRESENTATIONS OF AVALOKITEŚVARA

Now I want to look briefly at the pictorial representations of Avalokiteśvara in the wall-paintings and painted silk hangings from Dunhuang. In 1992 Henrik Sørensen published a study of representations of esoteric deities at Dunhuang. He concluded that Avalokiteśvara was by far the most represented esoteric deity in the wall-paintings. According to his statistics Avalokiteśvara is the central deity in 143 of the 198 esoteric wall-paintings at Dunhuang. The eleven-headed form is the most often represented, followed by the thousand-armed form and Cintāmanicakra form, with Amoghapāśa being the least popular. The majority of these paintings date from the mid-eighth century to the early eleventh: exactly the same period covered by the Tibetan Dunhuang manuscripts. The greatest concentration of the Avalokiteśvara paintings is in the tenth century, which is also the date of the majority of our Avalokiteśvara manuscripts.

No complete overview of the painted hangings from the library cave at Dunhuang has yet been published. In a brief survey of the British Museum holdings, I counted over seventy images of Avalokiteśvara, about a third of which related to tantric forms. These forms—such as Amoghapāśa and Cintāmanicakra, are the same set that is found in our Tibetan manuscripts. These images of Avalokiteśvara far outnumber those of any other single deity.

Most of the hangings have been dated to the mid-ninth to tenth centuries. Notable among them are a number of ma&'alas painted in an Indic (rather than Chinese) style, which may have been the work of Tibetans, although we must also consider the possibility of their being by Khotanese painters, or Chinese painters trained in an Indic style for the depiction of tantric deities. These include a ma&'ala of the thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara (kept in the New Delhi National Museum); three Amoghapāśa ma&'alas in which Avalokiteśvara is surrounded by four deities: Hayagrīva, Bh(ku)ī, Ekajātī, and another form of Avalokiteśvara (all in the Musée Guimet); an Amoghapāśa protective circle inscribed with a dhāranī (in the British Museum); and a sketch of an Amoghapāśa ma&'ala being used by a monk in a healing ritual (in the New Delhi National Museum). The last image seems to be related to the Amoghapāśa healing rituals found in the booklet ITJ401 and the concertina ITJ384.

Since the hangings were taken from the library cave, they derive from the same source as the manuscripts, probably a single monastery. Thus the presence of several Indic-style depictions of Avalokiteśvara and his ma&'ala in these hangings are particularly significant, and may well have been owned and used by the same Tibetan speaking people who wrote and used the manuscripts which we have been considering here.

V. CONCLUSIONS

The material that we have been reviewing should certainly lead us to revise the notion that we have no evidence for a cult of Avalokiteśvara in Tibet before the eleventh century. In these Dunhuang manuscripts, most of which are from the tenth century, there is ample evidence for a growing popularity of Avalokiteśvara, in which the deity has become a saviour for all kinds of ills, and the accomplisher of both worldly and transcendental aims.

But we must be careful here: I can see two reasons to doubt this conclusion. One is the geographical location of Dunhuang, marginal to the Tibetan cultural area, and more strongly under the influence of other cultures, especially Chinese. This is certainly something to keep in mind, yet the influences on the

Dunhuang texts may not be so different from those affecting more central areas of Tibet. If we look at the Dunhuang Avalokiteśvara texts which are also found in the Bka’ ’gyur, only two—both dhāranī-s of the thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara—are translated from the Chinese. Many more are translations from Indian texts. Also, we should remember that Tibetan histories generally relate the introduction of Buddhism back into central Tibet at the end of the so-called Dark Age of the tenth century from marginal areas to the east and west. In particular, Tibetan monks are held to have taken refuge in the countries of the Hor and Mi nyag, and to have settled in the region of Amdo (Mdo smad) in Northeastern Tibet—all areas close to the Silk Routes and the Dunhuang nexus. Thus, in this period, geographical marginality cannot be equated with cultural marginality.

The other factor that might make us wary of drawing the conclusion of Avalokiteśvara’s general popularity is the scarcity of the six-syllable mantra in this material. In the later tradition, the deity Avalokiteśvara is so closely associated with the six-syllable mantra that the two are almost interchangeable. The Tibetan historical sources that associate the introduction of Buddhism into Tibet from the very beginning with

34 See for example, Roerich 1976: 63–67. Stein (1959: 228–35) discusses this region apropos the location of the legendary kingdom of Gling. The identification of Hor and Mi nyag in this period is problematic, but they both certainly refer to the Amdo region, or beyond this, the Silk Road sites associated with the Uighurs and Tanguts.

35 While King Srong btsan sgam po’s advocacy of Avalokiteśvara has no basis in non-legendary material, it is not unlikely that Avalokiteśvara was first introduced to

the six-syllable mantra have been challenged by the recent studies mentioned earlier.35 In fact, the first firm Tibetan textual evidence for the centrality of the six-syllable mantra are the Bka’’chems ka khol ma and Ma"i bka’ ’bum collections, both of which date from the twelfth century.

Despite this lack of pre-eleventh century textual sources for the mantra, there is reason to believe that it was being popularised before the time of the Mani bka’ ’bum in an oral tradition. Matthew Kapstein has cited two textual sources that attest to the popularity of the six-syllable mantra by the eleventh

century. First, Ma cig lab sgron (10551145/1153) is supposed to have said that Avalokiteśvara and Tārā are the ancestors of Tibetans, and that Tibetan infants learn to recite the six-syllable mantra at the same time as they are just beginning to speak.

Second, La bstod dmar po, who lived at the same time as Dmar pa lo tsā ba, went to India to find a teaching to purify the negative actions he committed as a child. The teacher he found agreed to entrust a very secret teaching, with which he would remove the obstacles of this life and gain enlightenment in the next. The teacher, speaking down a bamboo tube inserted into the ear of the student, so that no one could overhear, said Om mani padme hūm. La bstod dmar po then had some doubts, thinking, “This mantra is repeated throughout Tibet by old men, women, and even children...”. He had to perform some unpleasant penance for his doubts, but the story ends well.

These examples suggest that the six-syllable mantra may have gained its status in Tibet as the salvific mantra par excellence outside of the textual tradition. This may have been accomplished by wander-

Tibetans during the seventh century, when the Tibetan empire expanded to Buddhist states of Central Asia such as Khotan. Perhaps, as some Tibetan historians have claimed, Khotanese missionaries propounding the Kāra"#avyūha sūtra reached Central Tibet even before the advent of the Tibetan empire. So we see in the dBa’ bzhed the story of the descent from

heaven of the six-syllable mantra onto the palace roof during the reign of Lha tho tho ri. Other texts relate that it was the Kāra"#avyūha sūtra which fell from heaven—the sūtra is, of course, the main source of the six-syllable mantra. In the Blue Annals, ’Gos lo tsā ba argues

that what really happened was that these texts were brought to the king by two figures including a Khotanese translator; but the king, being illiterate, was uninterested and sent them away (Roerich 1976: 38). This kind of missionary activity, in which Avalokiteśvara is employed as an ambassador for Buddhism, is suggested by the texts on the after-death state studies by Stein and Imaeda. These incorporated Buddhist elements, including the practice of relying on Avalokiteśvara, into an indigenous funeral rite.

36 Kapstein 2000: 48.

37 Roerich 1976: 1026-27.

ing religious preachers, the forbears of those who later came to be known as Ma&ipas, because they spread a simple form of dharma in which the six-syllable mantra was pre-eminent. If the six-syllable mantra was being popularised through an oral tradition in the ninth and tenth centuries, then we would not necessarily expect to find a widespread textual representation of the mantra during this period in our Dunhuang manuscripts.

We must also be careful not to be misled by the continuing Tibetan oral and folk tradition in which the six-syllable mantra tends to overshadow all of Avalokiteśvara’s many other mantras. In fact, the six-syllable mantra is by no means a ubiquitous feature of the tantric literature on Avalokiteśvara, even in the post-eleventh-century literature. The sādhanas of Avalokiteśvara employ a number of different dhāranī-s and mantras, of which the six-syllable mantra is only one among many. Most of the forms of Avalokiteśvara found in the Dunhuang texts, such as Cintāmanicakra and Amoghapāśa, are associated with other mantras, found in the dhāranī-s and tantras dedicated to those forms. Before the six-syllable mantra became so very popular, it would have been seen primarily as the Avalokiteśvara mantra of the Kāranavyūha sūtra. Traditions of Avalokiteśvara derived from any other scriptures would use the mantra specific to that

scripture. Thus in the sādhanas based on the Sarvatathāgatatattvasamgraha tantra use a mantra based on the seed syllables of Avalokiteśvara in that tantra: O% vajra dharma hrī (interestingly, this is itself a six-syllable mantra). Thus we may be asking too much of the texts when we expect to see more of the six-syllable mantra, and we are certainly not justified in equating the scarcity of that mantra with a lack of interest in Avalokiteśvara.

In any case, based on the Dunhuang manuscripts I would argue that that the composition of Avalokiteśvara material in the eleventh and twelfth century occurred in a culture in which Avalokiteśvara was already a very significant presence at the popular level of Buddhist practice and devotion. The advocates of Avalokiteśvara in the later diffusion of Buddhism in Tibet may have altered the appearance of the Avalokiteśvara cult, but it was already well-established before they began their work.

There is still much work to be done on the Avalokiteśvara texts. An important further step will be to establish what connections, if any, exist between the pre-eleventh century material and the later tradition, including the Mani bka’bum and the Bka’’chems ka khol ma, and the material brought from India by Atiśa and others. But this admittedly brief study shows, I hope, the benefits to be reaped from a comprehensive approach to the study of the Dunhuang manuscripts. These manuscripts can then be properly used to afford momentary illuminations of the dark period of the tenth century, before the great explosion of translation and textual creation in second diffusion of Buddhism in Tibet.

APPENDIX I: TIBETAN AVALOKITEŚVARA TEXTS IN DUNHUANG COLLECTIONS

Chapter 24 of the Saddharmapundarīka sūtra (on the manifestations of Avalokiteśvara)

[P.781] ITJ191 (concertina), ITJ351 + PT572 (booklet)

Byang chub sems dpa’ spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug yid bzhin khor lo la bstod pa Or.8210/S.95 (scroll), ITJ76/3 (booklet), ITJ311/3 (pothī), ITJ369/3 (pothī; incomplete), PT7/4 (concertina)

‘Phags pa spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug la bstod pa ITJ314 (pothī): Spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug gi mtshan brgya rtsa brgyad pa [P.381] ITJ315 (concertina), ITJ316/1 (concertina), ITJ351/2 (booklet), ITJ379/2 (concertina), ITJ385/3 (concertina), PT7/5 (concertina), PT11 (concertina), PT23 (concertina), PT24 (concertina), PT32 (concertina), PT107 (concertina), PT109 (concertina), PT110

(poth?), PT111 (concertina), PT753 (fragment)

Byang chub sems dpa’ spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug gi rigs sngags ITJ453 (concertina), ITJ513 (concertina), PT356 (fragment)

’Phags pa byang chub sems dpa’ spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug phyag stong spyan stong dang ldan pa thogs pa myi mnga’ ba’i thugs rje chen po’i sems rgya cher yongs su rdzogs pa zhes bya ba’i gzungs [P.369] (tr. from Chinese) ITJ214 (pothī), PT420 (booklet), PT421 (booklet)

’Phags pa spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug phyag stong spyan stong du sprul pa rgya chen po yongs su rdzogs pa thogs pa med par thugs rje chen po dang ldan pa’i gzungs

[P.368] (tr. from Chinese) PT365 (pothī) Spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug zhal bcu gcig pa’i gzungs [P.373] PT45 (concertina) ’Phags pa spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug gi snying po [P.372] ITJ337/4 (concertina), PT75 (scroll) Don yod zhags pa’i snying po / gzungs [P.366] ITJ311/1 (pothī), ITJ312/2 (pothī), ITJ372/2 (scroll), PT7/7 (concertina), PT49/4 (scroll), PT56 (pothī), PT105 (scroll), PT264 (frag)

Others

ITJ323/2 (12:74-92; pothī), PT1/5 (scroll)

Sādhana

Various rituals including homa (Kriyā/Caryā) ITJ401 (booklet), PT327 (scroll) White, one-faced, two-armed Avalokiteśvara (Yogatantra) PT331 (single sheet), ITJ583/2 (concertina), ITJ509 & PT320 (concertina) Amoghapāśa ma&'ala (Yogatantra) ITJ384/2 (concertina)

Red, one-faced, two-armed Avalokiteśvara (Mahāyoga) ITJ754/6 (scroll) TEXTS ON THE AFTER-DEATH STATE Gdug gsum ’dul ba ITJ420 (booklet), ITJ421/1 (booklet), ITJ720 (fragment), PT37/1 (booklet) Lha yul du lam bstan pa PT37/2 (booklet), PT239 recto (concertina), PT733 (fragment) Funeral rites ITJ504 (fragment), PT239 verso (concertina)

APPENDIX II: SELECTED PAINTED HANGINGS

Avalokiteśvara ma&'ala: Stein painting 66 Avalokiteśvara, Indic style: Stein Painting 55 Cintāmanicakra with eight bodhisattvas and four kings: Stein Painting 61 Thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara with entourage: Stein Painting 35, MG.17775 Thousand-armed Avalokiteśvara, Indic style: Delhi Museum Ch.xxviii.006 Eleven-headed Avalokiteśvara: EO.3587 Amoghapāśa: MG.2306

Amoghapāśa protective diagram according to the Amoghapāśa dhāranī sūtra Stein Painting 18 Amoghapāśa (blue) ma&'ala w/ Hayagrīva, Bh(ku)ī, Ekaja)ī and another form of Avalokiteśvara, Indic style: EO.1131 Amoghapāśa ma&'ala, similar to above, Indic style: MG.26466 Amoghapāśa ma&'ala, with five buddhas and many other deities, Indic style style: EO.3579 Amoghapāśa ma&'ala sketch for healing ritual (deity represented by a vase): Delhi Museum Ch.00379

APPENDIX III: AVALOKITEŚVARA TEXTS IN THE LDANDKARMA

78 & 101. snying rje chen po padma dkar po (P.799)

79. dam pa’i chos pad ma dkar po 114. za ma tog bkod pa (P.784)

157. spyan ras gzigs zhes bya

170. seng ge’i sgra bsgrags pa (P.385/387?) 316. don yod zhags pa’i rtogs pa chen po (P.365?) 343. spyan ras gzigs yid bzhin ‘khor lo sgyur ba’i gzungs (P.370?) 347. don yod zhags pa’i snying po (P.366) 352. spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug yid bzhin gyi nor bu ‘khor lo sgyur ba’i gzungs 366. spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug zhal bcu gcig pa’i gzungs 368. snying rje mchog

388. spyan ras gzigs kyi yum (P.399) 440. spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug gi mtshan brgya rtsa brgyad pa (P.381) 459. spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug la phyag na rdo rje ‘dzin rnams kyi bstod pa 460. spyan ras gzigs dbang phyug la snying rje’i bstod pa

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Yü, Chün-fang. 2001. Kuan yin: the Chinese Transformation of Avalokitesvara. Columbia University Press: New York.

Davidson, Ronald M. 2002. Indian Esoteric Buddhism: a Social History of the Tantric Movement. New York: Columbia University Press.

Imaeda, I. 1979. Note préliminaire sur la formule o% ma"i padme hū% dans les manuscrits tibétains de Touen-houang. In Michel Soymié (ed.) Contributions aux études sur Touen-Houang. Geneva/Paris: Librairie Droz.

––––1981. Histoire de cycle de la naissance et de la mort. Geneva/Paris: Librairie Droz. Kapstein, M.T. 2000. The Tibetan Assimilation of Buddhism: Conversion, Contestation, and Memory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lalou, M. 1939. A Tun-huang prelude to the Kara"#avyūha. Indian Historical Quarterly XIV(2), 398-400. ––––1953. Les textes bouddhiques au temps du roi Khri-sro*-lde-bcan. Journale Asiatique 241(3), 313-53. Macdonald, Ariane. 1971. Une lecture des Pelliot tibétain 1286, 1287, 1038, 1047, et 1290: essai sur la formation et l’emploi des mythes politiques dans la religion royale de Sro*-bcan sgam-po. In Ariane Macdonald (ed) Études tibétaines dédiées à la mémoire de Marcelle Lalou. Paris: Libraire d’Amerique et d’Orient Adrien Maisonneuve.

Matsumoto, E. 1937. Tonkō ga no kenkyū (A Study of the Dunhuang Paintings). Tokyo: Toho Bunko Gakuin. Meisezahl, R.O. 1962. The Amoghapāśah (daya-dhāranī: the early Sanskrit manuscript of the Reiunji critically edited and translated. Monumenta Nipponica 17, 265-328. Roerich, G.N. [1949] 1976. The Blue Annals. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Rong Xinjiang. 2000. The nature of the Dunhuang library cave and the reasons for its sealing. Cahiers d’Extreme-Asie 11: 247-76. Scherrer-Schaub, Cristina and George Bonami. 2002. Establishing a typology of the old Tibetan manuscripts: a multidisciplinary approach. In S. Whitfield (ed.) Dunhuang Manuscript Forgeries. London: The British Library.

Sørensen, H. 1992. Typology and iconography in the esoteric Buddhist art of Dunhuang. Journal of Silk Road Studies: Silk Road Art and Archaeology 2: 285–349. Stein, R.A. 1959. Recherches sur l’épopée et le barde au Tibet. Paris: Presses universaires de France. ––––1970. Un document ancien relatif aux rites funéraires des Bon-po tibétains. Journal Asiatique CCLVII, 155–85.

Studholme, A. 2002. The Origins of O% Ma"ipadme Hū%. New York: SUNY Press. Takeuchi, T. 1995. Old Tibetan Contracts from Central Asia. Tokyo: Daizo Shuppan. ——1997-1998. Old Tibetan Manuscripts from East Turkestan in the Stein Collection of the British Library. 3 vols. Tokyo/ London: The Toyo Bunko and The British Library.

Tucci, G. 1980. The Religions of Tibet. Berkeley: University of California Press. Die Religionen Tibets (1970) translated by Geoffrey Samuel].