Tantra as Action

AN INTRODUCTION TO TANTRA

Almost every study of Tantrism begins by apologizing.

Robert L. Brown

The reason for the apology is simple, and points us in the direction we want to go: there is no consensus among scholars as to what the term Tantra actually refers. It is, in fact, a Western concept (as is Hinduism). Tantra is the result of more than a century of colonial scholars visiting India and seeing a discrepancy between normative Vedic Brahmanism and some shocking antinomian practices that we, in the West, would probably term “magic,” or that equally slippery concept, “shamanism.” Tantra became identified as a separate philosophy and was divided into Hindu Tantra and Buddhist Tantra—which is a misleading distinction that will get us nowhere in the end and which, logically, makes no sense if Tantra really is a separate philosophy.

In fact, according to André Padoux, one of the leading scholars of Tantra in the world today:

Neither in traditional India nor in Sanskrit texts is there a term for Tantrism; no description or definition of such a category is to be found anywhere. We know also that, more often than not, Tantric texts are not called Tantra.6

Part of the problem lies in the West's reliance on the written word—on textuality and on textual analysis. Scholars have discovered books called Tantras that were written by Buddhists and still others that were written by Hindus—i.e., non-Buddhist Indians. This seems to indicate that there is some fundamental difference between the two practices. In fact, on the level of theory, there are differences, even important ones. On the level of practice, however, they are much the same. And Tantra is all about the practice.

And this is the point I want to make, and the direction in which we want to go.

There are two main religious currents that gave rise to the phenomenon known as Tantra: Hinduism and Buddhism. Hinduism is a catch-all term for what may better be described as “Hindu religious traditions,” for there is no single religious faith that can be described as Hinduism. Rather Hinduism is a wide variety of religious and spiritual experiences encountered on the sub-continent of India. While we will continue to use the term Hinduism for the sake of convenience, it should be noted that we do that primarily to distinguish the indigenous religions of India from Buddhism, which came much later.

There are scriptures that are considered Hindu; these include the Vedas, the Upanishads, and the Puranas, among others. There are also the famous epic poems the Ramayana and the Mahabharata that are just as important to the Indian people and that also were introduced into Indonesia at an early date. These epics were embraced by the population there as well, finding one manifestation in the famous wayang kulit, the shadow puppet theater that has tremendous cultural, social, and religious importance for the Javanese.

It was Vedic Hinduism that provided the rigid social structure known as the caste system. No one really knows how old the Vedas are, but they can be reliably dated to sometime in the second millennium BCE. Written in Sanskrit, they may be considered the core texts of Indian culture and faith. They contain instructions for the various rituals that should be performed, but they also contain medical knowledge, astronomical lore, and—in the case of the Atharva Veda, the so-called “fourth Veda”—occult texts as well.

One of the primary rituals of Vedic Hinduism is the Homa, or fire ritual, sometimes also called the Agnihotra (agni is the Sanskrit word for “fire”; hotra means “healing”) when used to refer to the twice-daily fire offering, the most basic form of the ritual. This rite is reminiscent of the fire rituals of the Zoroastrians and has many variations, depending on their purpose. It is considered quite ancient and probably pre-Vedic. Basically, a fire is created in a special device using consecrated material—often ghee (clarified butter), as well as milk, honey, or other substances specific to the purpose. These form the basis of offerings, which are accompanied by the relevant prayers and meditations. The device or fire pit is often in the shape of an upside-down pyramid that allows the fire to burn quite hot. The cardinal direction practitioners face during the Homa ritual is of great importance, as are the number of Brahmins who are performing it and the purpose for which it is being performed.7 Even in the relatively staid Vedic practice of the Homa ritual, the symbolism is often interpreted quite deliberately in a sexual manner, with the fire representing the yoni, or sexual organs, of a goddess.8 The Homa ritual eventually found a place in Tibetan Buddhist practice, as well as in Japanese Shingon ritual. Its practice is amply represented in the Tantric temples of Java.

Buddhism, of course, owes its origins to its founder, Siddhartha Gautama, who it is said was a prince living in northeast India sometime in the sixth century BCE, or perhaps a little later. While not much is known definitively about his life, most sources agree that he was born to a family of privilege and he is usually referred to as Prince Siddhartha. At the age of twenty-nine, he decided to end his life of ease and isolation from the rest of the world and ventured outside the palace walls to see real human existence as it is.

According to canonical Buddhist sources, he was astonished and saddened by the sights of sickness, death, and misery that were everywhere in the world, and he devoted himself to finding a solution to the human condition. After years of false starts with a variety of gurus and ascetic disciplines, he chose silent meditation. During the course of this practice, he realized that the root of all suffering was attachment: to things, to people, to ideas, and particularly to the concept of an individual self. The solution, he claimed, was non-attachment, even to the self, even to the gods. Because humans were attached to objects that gave them no real joy or happiness, he came to the conclusion that these objects did not really exist in any kind of absolute sense, but were illusions and impediments to spiritual liberation—here understood as freedom from the endless cycle of birth and rebirth. By grasping after things, we remain unsettled spiritually. In fact, by assuming that we have a soul at all (or an ego, a self, a personality), we identify with the ephemeral, with a string of events that we believe constitute individuality.9 By withdrawing from the world—or, at least, from lusting after the things of the world—we begin to find a well of inner peace.

While accepting that we are making a much longer and more detailed story too short, we can say that the Buddha attained an exalted state of consciousness—illumination, or enlightenment, the ultimate stage—and then proceeded to teach others how to reach the same stage. The methods utilized by Buddhists involve intellectual study, meditation, and a kind of psycho-spiritual practice of negation in order to reach a perfect state of non-attachment. Among the Eastern Orthodox monks of the Christian world, this is sometimes called apophatism. It is a way of knowing God by saying what God is not, as opposed to what God is, since God is essentially unknowable. To a Buddhist, however, there is no God at all. God is perhaps the supreme illusion, the last obstacle on the way to perfect illumination. The end result of Buddhist apophatism is the realization that there is only a kind of absolute, albeit blissful, Void.

Buddhism is non-dualist for obvious reasons.10 In Buddhism, there is no “this” and “that.” The multiplicity of things perceived is an illusion, a kind of magic theater that distracts the spirit from true understanding. The goal of Buddhist practice is to achieve perfect Unity, a state where there is no “I” and “you” and “it,” but only pure essential Being. However, one cannot arrive at that destination overnight, or merely by thinking very hard about it. It requires a program of phased initiations involving strenuous forms of meditation and ritual practice, and these vary from school to school, from sect to sect.

The oldest form of Buddhism, known as Theravada, is found today primarily in Southeast Asia, especially in Thailand and Sri Lanka. Mahayana Buddhism, a later form, is discovered in northern Asia: in China, Japan, and Korea. In Tibet, however, there is a third form, known as Vajrayana Buddhism, that is virtually indistinguishable from Tantra, but that has roots in Mahayana Buddhism as well as in the indigenous religion of Tibet.

Theravadin Buddhist scriptures include the Pali Canon, the oldest known Buddhist writings, which contain a variety of what are known as suttas (or, in non-Pali usage, the more familiar sutras). These include instructions for Buddhist disciples and discipline, as well as deeper articulations of Buddhist thought. One of the most famous of these is the Dhammapada, which has undergone several translations (including that by Max Muller in his Sacred Books of the East series), and the Brahmajala Sutta.

Mahayana scriptures are of later creation, but are based—to a certain extent—on some of the earlier Theravadin suttas. The origins of Mahayana Buddhism are in dispute, but the earliest Mahayana writings date from about the first century CE and are largely known from their Chinese- and Tibetan-language originals. While Theravada is thought to represent a pure form of Buddhism, Mahayana is sometimes characterized as a “popular” form of the same belief system. Perhaps the most famous of the Mahayana scriptures are the Diamond Sutra, the Lotus Sutra, and the Heart Sutra, the latter of which is only sixteen sentences long and contains the famous phrase: “Form itself is emptiness; emptiness itself is form.”

In India, Buddhism reached an early crescendo, but had lost a great deal of its influence by the beginning of the medieval period. The Hindu religious tradition, however, continued and became stronger. As India moved out of its Buddhist period, Tantra grew quickly and may be said to have come into its own.

As mentioned, there are actual texts known as Tantras. These are largely in the form of dialogues between the Indian God Shiva and his female consort. This consort can be identified variously as Parvati, as Uma, as any one of dozens of other goddesses, or simply as Shakti. In any case, the female consort represents power: spiritual power. The whole focus of Tantra is on this power, which is believed to pervade every aspect, every particle, of the universe. By aligning oneself with this power, one can also effect material ends. For that reason, Tantra has had a following among those who find the traditional methods of worship, the caste system, and the Brahminical hierarchies stifling or inefficient, and among those who wish to have direct experience of the divine. The motivation for this may be purely spiritual—enlightenment or nirvana— or it may be purely mundane—for instance, obtaining a lover, wealth, or health. Or it may be both at the same time. In this, Tantra is virtually identical to Western forms of ceremonial magic and, indeed, the two systems have a great deal in common.

Tantra cuts across denominational boundaries, as does Western magic. One can be Jewish, Catholic, or Protestant—or anything else, for that matter—and still be a magician in the Western sense. Magic is a practice, as opposed to a coherent, carefully articulated philosophy, although it is predicated on a certain view of the interconnectedness of the universe, the doctrine of correspondences, and the idea that knowledge of the inner workings of the universe can give a person the ability to effect change at a distance using methods that seem to defy normal concepts of cause and effect. It is also based on a belief that you can become “as a god.” Indeed, some magicians are drawn to the practice because they believe it enables them to commune directly with the divine, without the encumbrance of a high priest or other middle-man. It is a practice that is available to anyone, from clergyman to commoner, as is Tantra. And it is a threat to the status quo—politically, religiously, and culturally.

As is Tantra.

Like magic, Tantra is a technology. It is a means to an end. It involves the manipulation of consciousness through ritual, the end result of which has been pre-determined by the practitioner. And, as a technology, it makes use of all available materials. The tools of Tantra are the tools of consciousness—the five senses. Virtually anything can be employed in a Tantric ritual, from food and wine, to drugs, icons, incense, music, and sex, but always with a concentration on the physical body itself. While many of the texts called Tantras are deeply profound in their explanations of how reality is structured—using either dualist or non-dualist approaches—the attraction of Tantra is found mainly in the practices that permit devotees access to altered states of consciousness and the elevation of the mind to spiritual realms—i.e., to illumination.

Without these practices, the texts themselves are virtually useless. The texts are methodologies that are meant to be applied, instruction manuals intended to be used. They are recipe books, in a sense—and imagine how useless a recipe book is in the hands of someone who does not cook. This is the distinction that can be made between normative scripture-based religions like Christianity and Tantra. In Christianity, the Bible is the ultimate spiritual authority and, for many fundamentalist Christians, the only authority. Reading the Bible and preaching the Bible constitutes the core experience. (Conversely, a mystic may observe that those who can, do; while those who can't, preach.) A Tantrika (a practitioner of Tantra) may well ask: How can we use the Bible to attain altered states of consciousness? How can we use the Bible to come directly into the presence of the divine? Is the Bible a manual of operation? Does the Bible teach how to breathe, how to chant, how to visualize?

That the Bible does none of these things is obvious. However, there were groups of believers—both Jewish and Christian—who analyzed Biblical writings to derive physical and spiritual practices from them. These were the Kabbalists, the mystics, the magicians. Their role models were Ezekiel, Moses, and Solomon (and, for Christian Kabbalists, the Book of Revelation). They wrote their own texts, their own “Tantras”: the grimoires. In Asia, the Tantrikas based their ritual syntax on their own spiritual culture—the Vedas, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata—and eventually developed the wider and more specific field of texts known as the Agamas, the Samhitas, and of course the Tantras themselves. Thus, there would be greater communication between a medieval European magician or sorcerer and a medieval Indian Tantrika than there would be between a Catholic priest and a Brahmin. Indeed, there are respected scholars in this field who have promoted the idea that there was actual contact between Kabbalists and Tantrikas centuries ago, with a resulting cross-fertilization of ideas and practices. We will come to that later.

It is my intention to demonstrate that the practice of Tantra, in some sense, takes place outside the philosophical or theological structures that have been imposed on it, either by adherents of the different religions through which Tantric texts have appeared over the centuries (most notably Indian religions, but also Chinese and Japanese faith systems) or by foreign observers such as English colonial scholars and commentators. Indonesia is a useful laboratory for this investigation, because many of the religions of the world have had an impact on its culture—especially in Java—from the Hindu religious traditions and Buddhism (in all its forms) to Islam and Christianity, and even including such modern-day spiritual movements as Theosophy. With all that, however, certain indigenous practices and beliefs have survived the imposition of foreign dogmas and faith systems ever since the beginning of Java's recorded history. From this perspective, Javanese mysticism has as much to say to us about how Tantra not only survives but thrives in a multireligious, multi-cultural environment as does any study of Tantra in its indigenous land, the Indian sub-continent.

In order to accomplish this, we will look first at the history of Tantra and even offer some ideas concerning its origins. Using this as a roadmap, we will then approach Javanese mysticism—kejawen and kebatinan— and then Java's Tantric temples themselves to understand why they were designed the way they were. We will look at present-day Javanese practices that bear striking similarity to Tantra as traditionally understood. Then we will use what we have learned from this fusion of theory and practice, text and ritual, to take a look at modern Western ideas of Tantra, as enshrined in the rituals and concepts of modern esoteric and hermetic societies, Western and Eastern.

During this investigation, we will reveal some of the most closely guarded secrets of these groups, secrets that are well-known to privileged spiritual elites and suspected by interested non-initiates. We will see how European alchemy was influenced by concepts familiar to the Tantrikas, and even how Chinese alchemy can help us understand both the European and Indian versions. We will even find ourselves startled to learn that Jewish mysticism also has a great deal in common with Indian Tantra, and that some aspects of Tantra—like the idea of Kundalini—may have had their origins in the ancient Near East.

Tantra as Action The ideological aspect of the Tantric vision is the cosmos as permeated by power (or powers), a vision wherein energy (sakti) is both cosmic and human and where microcosm and macrocosm correspond and interact.11

In the West, a common distinction is made between two forms of esoteric spirituality: magic and mysticism. While this distinction is purely arbitrary and not applicable in any kind of absolute sense, it provides a helpful introduction to the question of where Tantra should be located within the general field of religion or the more specific area of esotericism.

This distinction also asks us to think about two forms of religious experience and expression: the exoteric and the esoteric. When most people profess a religious affiliation, they are referring to an exoteric form of spirituality—for example, Christianity, Islam, Judaism, or Buddhism. These are often scriptural denominations with religious “specialists” or “professionals” like priests, rabbis, imams, or monks. The average person is conscious of their faith in rudimentary ways, in terms of what behavior is proper and acceptable, or what duties their religion prescribes. There is often a specific place used for the performance of religious obligations and rituals—a mosque, synagogue, church, or other physical location. In addition to all of this, there is also a religious calendar with days or periods that are more sacred or meaningful than others. Thus, there is sacred time, sacred space, and a text—whether written or oral—embodying the precepts of the faith as well as religious professionals who interpret the scriptures, perform rituals, lead prayers, and whose opinion in matters of law and practice is considered authoritative.12

Esotericism, on the other hand, is intensely individualistic. Where exoteric spirituality often relies on the society of like-minded individuals who are members of the same faith and thus can be expected to share identical beliefs and loyalties, esoteric spirituality is conscious of being apart from society at large and estranged in some essential ways from the base or root religion, the exoteric form. Thus, there are esoteric forms of most of the world's major religions. Kabbalah, for example, can be considered an esoteric form of its exoteric root, Judaism. Sufism can be considered an esoteric form of Islam. Indeed, Islam recognizes two different manifestations of its faith: lahir, the exoteric form, and batin, the inner or esoteric form.

Esotericism finds its expression in non-canonical texts, in beliefs that are refinements of or extrapolations on the base or root belief of a faith, and most especially in acts that would be considered questionable by orthodox believers, if not actually forbidden or tabu. Esoteric practices may take place according to different structures of sacred space and time, and they may be under the control of an alternate hierarchy of specialists. Tantra is, itself, an esoteric practice and may represent one of the oldest forms of esotericism in the world, if we are to accept a pre-Aryan origin for some of its most cherished characteristics, like worship of a divine Mother and the concept of sacred sexuality.

As mentioned above, scholars are divided as to the definition of Tantra, the date of its first emergence as a coherent practice, and even whether Tantra arose out of Buddhism first and then became adapted to Hinduism, or the other way around. While these are all compelling questions, and the answers would do much to illuminate the history of the sub-continent, they need not concern us much at this point. We will come back to them again and again over the course of this work, and maybe we will obtain a clearer picture as we go along.

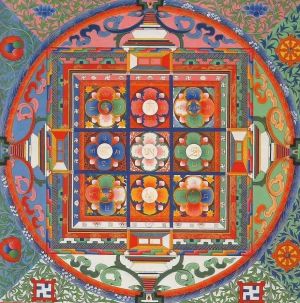

Tantra is primarily a practice, and can be considered an esoteric, rather than an exoteric, one. It is a means of attaining altered states of consciousness, spiritual illumination, and even occult powers and abilities known as siddhas. It involves the identification of the human practitioner with a god or goddess and the partner with a deity of the opposite gender—but that comes later. In the beginning, a Tantrika—that is, a person who belongs to any one of a variety of Tantric sects or who has received initiation from a Tantric guru—spends a great deal of time in meditation, doing physical exercises that are familiar to us from yoga (pranayama, asana, etc.), and performing a range of puja, or ceremonies and rituals. Most authorities agree that mantras (specific words of power, recited over and over), mudras (ritual gestures), and yantras (mystical diagrams) are main features of Tantric ritual. Because the practice of Tantra takes place within a specific context—usually Buddhist or Hindu—the prayers, meditations, mandalas, and rituals will all be developed within that context, and based on that particular philosophy. The end result, however, will be the same.

The two main philosophies found in any scholarly description of Tantra are dualism and non-dualism. Non-duality, or advaita, is the basic philosophy associated with Buddhism. A Buddhist believes there is no real polarization of male/female, god/human, reality/unreality, but that these concepts and their divisions are all illusions and the source of sorrow and discontent. A dualist belief, on the other hand, is one in which the “polarities” of creation are acknowledged and celebrated. To a Tantrika, both of these philosophies are, in a sense, true.

A Tantrika understands that the duality being employed in Tantric ritual is a means to an end: union with the Divine. In other words, we might say that a Tantrika uses dualist ritual to attain a non-dualist end.

Buddhists can be accused of the same thing. A visit to any Buddhist temple will introduce the seeker to a variety of statues of different aspects of the Buddha and even, depending on the type of Buddhism and the location of the temple, various other deities specific to that location. For instance, a Chinese Buddhist temple will be filled with statues, not only of the Buddha, but of other Chinese saints and even of the famous goddess Guan Yin, the Goddess of Mercy who is identified with the Indian god Avalokitesvara (of whom it is said the Dalai Lama is an incarnation). All of this certainly seems like a lot of unnecessary duplication in a belief system that emphasizes non-duality, but it is understood that people in general require these images in order to approach the esoteric, inner truth of Buddhism that all is illusion and that the only refuge we can take is in the Buddha. From that point of view, a scholar may interpret these religious trappings as mnemonic devices or even as a kind of memory palace, enabling Buddhists to navigate the terrain of their own culture and consciousness in a somewhat orderly way in order to become divested of the useless accoutrements of conventional religion.

Yet, as we shall see, the entire field of Tibetan Buddhism (as an example) is basically Tantric Buddhism, the form known as Vajrayana Buddhism. The famous Tibetan Tantric texts, like the Kalachakra Tantra, are veritable treasure troves of Tantric information and instructions for practice. There is no way to understand this apparent dichotomy between the non-dualist, basically anti-theist approach of orthodox Buddhism on the one hand and these arcane and complex ritual procedures on the other, unless we accept that Tantra is a technology, a tool for reaching the state of consciousness necessary for directly experiencing the bliss of advaita, and that the philosophies that seem embedded in Tantric texts refer more to the method itself than to an overarching philosophy of life or religion. Even this statement, however, can be hotly contested by specialists in the field who place more emphasis on the philosophy—what I choose to call the theory—of Buddhism than on the practice.

With the type of Tantra we encounter in a non-Buddhist context, however, we are on familiar ground. The emphasis on the dualities of male/female, god/goddess, etc. are clear and unequivocal; but the union of these opposites is just as clear and important. To a Tantrika, everything in creation is basically sexual; everything we see, touch, feel is the result of a cosmic sexual reproductive act. The human act of sexual intercourse is a reenactment of the original, divine intercourse. By becoming totally aware and spiritually prepared prior to consummating a sex act with a similarly trained partner, one is able to experience that moment when all existence came into being or, perhaps, the moment a split second before. This suggests that, in common with many forms of mysticism, the transcendence of the divine may be experienced in its immanence in all things—that the route from the microcosm to the macrocosm is through the one act that is common to both, the sex act. This act is a tangential point between the two forms of consciousness.

The challenge, especially for a Westerner with a great deal of baggage when it comes to sexuality, is in reducing the prurient aspect of Tantra as much as possible. Tantra does indeed sacralize sexuality, but the reverse is also true. Sexuality itself becomes a sacred act that should not be abused for the sake of immediate gratification. Instead, sexuality sacralizes the universe. Tantra is a way of understanding a sacred process. In this way, Tantra has been used to understand chemical as well as biological reactions and to formulate psychological theories. It can even be applied to Western alchemy and Jewish mysticism.

The tremendously colorful and complex images of gods and goddesses in ecstatic embrace that we encounter in Tantra are not meant to titillate, but to instruct. But how do we use blatantly sexual images—a kind of religious pornography—to instruct us in spiritual matters?

The Body as Tantric Laboratory I believe that precisely at the bottom of all our mystical states there are body techniques which we have not studied, but which were studied in China and India, even in very remote periods. I think that there are necessarily biological means of entering into “communication with God.”13

The core tension of Indian spiritual practice—and, indeed, of many religions around the world—is found in the ambiguous relationship between the spirit and the body, or between the invisible and the visible. In many religious cultures, the body is conceived as a source of sorrow, of attachment to physical desires, of ignoble yearnings, of pollution. It is a locus of danger that needs to be controlled by the mind of its owner. The desires of the body are virtually all expressions of what are considered negative forces—lust, hunger, thirst, sleep, etc.—as if the body were a Sherman tank with a pacifist as its driver. The tank is all metal and armor and munitions, with a giant cannon, mindless but lethal; in the hands of a trained soldier, it will cause terrible damage to the community. Thus, there is a need for a pacifist at the controls who will use the tank for other purposes, perhaps to plow the earth for crops. And one can only be sure that the people at the controls are pacifists if they are checked on a constant basis to insure that their purity is intact and to prove that their hands are where they are supposed to be at all times.

The imposition of celibacy by the Roman Catholic Church (a relatively late development in Church history) is one example of this discomfort with the body and the assumption that bodily needs are an obstacle to union with God. In addition to celibacy, other controls of the body include fasting (particularly during Lent) and prolonged periods of prayer in sometimes uncomfortable positions. In extreme cases, self-flagellation and other methods are used to emphasize the inherent sinfulness of the human body and the need to dominate it through brute force. The French postmodern philosopher Michel Foucault has had a great deal to say concerning the control of the body by governments, churches, the medical profession, the penal system, and others. We do not need to revisit those arguments here, except to point out that a Foucaldian interpretation of our theme—sacred sexuality—would be a welcome addition to this field of study.14

The Catholic approach to the body has been to suppress sexual desire as much as possible, not only among its clergy, but also in its commands to the faithful to avoid all forms of birth control (save the rhythm method) and to engage in sex only if procreation is possible, thus ruling out not only birth control, but also forms of sexual expression that do not lead to conception. This is an attitude that has made its way into many other Christian denominations as well. There are strains of Gnosticism in this position: the idea that matter itself is evil, a creation of the Demi-Urge, and that only spirit is good and clean and pure.

In the Tantric tradition, however, every effort is made to address this problem rather than simply suppress it. There are two general schools of thought concerning the human body that may be discerned in a review of both Hindu and Buddhist Tantra. The body can be conceived as a vehicle to liberation and enlightenment in both schools, but the utilization of the body is problematic. One approach is to “spiritualize” the body and the sexual act to such an extent that the body's natural urges are transcended through intensive physical and mental practices, sublimating the sexual urge and transforming it into an engine of spiritual force. This is a form of denial that would be consistent with Catholic ideas, were it not for the active involvement of the Tantrika in the contemplation of detailed depictions of gods and goddesses in sexual embrace, the study of descriptions of the sexual act that could be construed as lascivious to Western sensibilities, and ritual enactments of sexual liaison with spiritual forces.

In some forms of Tantra, one is expected to transcend normal physical sexuality by confronting it head-on, albeit symbolically. In other forms, however, we detect a decidedly “hands-on” approach in which sexuality is considered a vehicle for liberation (just as in the former example). There is an important difference, however. In these forms, the sex act is made part of an elaborate ritual (the most famous—or infamous—of which is the Ritual of the Five Ms, or pancatattva). This practice involves meditation, mantras, yantras, mudras, and spiritual initiation, as well as—or as integral elements of—actual intercourse. While the symbolic aspect is very much part of the ritual and essential to its success, the active participation of sexual partners provides another level of engagement through full investment of the psycho-biological instruments of two, very human, partners.

In fact, it may be a requirement that these acts are carried out, not only symbolically, but in actuality.

According to authorities on the Vedic fire ritual (the Homa), for instance, we are told that one may perform the Homa symbolically (the Inner Homa, a meditative rite) if there are no “requisite offerings” at hand. However, if the offerings are available, it is not permitted to perform the Inner Homa only; the Outer Homa (i.e., the full ritual) must be performed.15

Logically, then, if the offerings are available in the Tantric ritual known as the pancatattva or pancamakara (the famous “five Ms”), which requires the breaking of five Vedic tabus—drinking wine (madya), eating meat (mamsa), eating fish (matsya), eating grain (mudra), and sexual intercourse with a partner who may not be married to you (maithuna)—then it follows that they should be part of the rite, not only in a symbolic sense, but in an actual sense as well. Bear in mind, however, that the “inner” part of the ritual must also be performed and not only the outer observance.

How Old Is Tantra? Again, we enter the realm of apology. We simply don't know. Some important Tantric texts can be dated reliably to the seventh century ce, but Tantric practices are certainly much older than that.16 One of the four Vedic scriptures, the Atharva Veda, is sometimes considered a Tantric text because of its focus on magic and occult powers, which leads some to think that Tantra can be dated to the Atharva Veda. Unfortunately, however, that is not the case, since scholars are divided as to whether the Atharva Veda represents a scripture that was composed after the first three Vedas and is therefore relatively late, or if, in fact, the Atharva Veda represents a tradition that is older than all four! Regardless, however, the Vedas as a group are quite ancient, with some estimates placing their origin sometime in the second millennium BCE. The written Tantras, with their emphasis on the esoteric aspects of Vedic religion, must therefore be considerably newer.

Generally speaking, the Vedas represent an entire body of knowledge, from astronomy to architecture and medicine, and from history to public policy. The rituals associated with the Vedas are performed by a priestly caste, the Brahmins. Vedic society was divided into four basic castes, or varnas, with the Brahmins at the top of the pyramid, followed by the Kshatriyas (the warriors and rulers), the Vaishyas (merchants, traders; Gandhi was a member of this caste), and the Sudras (laborers). Outside the system is the class of Untouchables, the Dalits, who number roughly 170 million people in India, or 13 percent of the total population—in contrast to the Brahmins, who represent only roughly 5 percent. In actuality, there are many sub-castes as well, so we are talking about a massive stratification of society that includes 3000 actual castes and about ten times that number of sub-castes. Since Independence, however, much of the caste system has been overhauled so that members of different castes may marry, for instance, but the plight of many of the lowest castes—and especially of the Untouchables—remains a serious problem in India. This is pointed out so that the reader may better appreciate the role of Tantra in this country of strongly divided social roles.

The caste of Brahmins is purity-obsessed. Brahmins may not eat food unless it has been prepared by other Brahmins, for example. They may only marry other Brahmins. Indeed, no one may even look at a Brahmin (or a fire) while urinating or defecating. For the Brahmins, the body itself is the vehicle for purity and for divinity. The care of religion and ritual is their province, their sacred responsibility. They cannot carry out their duties if they are in a state of ritual impurity. For Brahminical priests, purity of the body is analogous to purity of the soul; in a very real sense, “cleanliness is next to godliness.”

Purity is a hallmark of many religious practices around the globe, of course. Ritual purity is important in Judaism, for instance, as well as in Islam. The Qumran sect that gave us the Dead Sea Scrolls was also fanatically interested in questions of ritual purity. Thus this idea that bodily impurity is an obstacle to full participation in the rites of the community is very old, and relatively widespread. Yet, the idea of willful transgression of the purity laws is also old and widespread, and that is where Tantra comes in.

From Tantra to Tantroid—Transcendence through Transgression

For our purposes, I suggest we occasionally make use of a term that has gained some ground in academic circles owing to the difficulty of accurately defining what is, and is not, Tantra. This word, “tantroid,” will enable us to discuss this subject in a provisional way without committing ourselves to a narrow interpretation, especially when we come to discuss Javanese practices in particular. According to Bruce M. Sullivan, we can characterize a practice as tantroid if it has the following three characteristics: fierce goddesses, transgressive sacrality, and identification with a deity.17

With some modification, we can apply this scheme to what we will see of Javanese practices, especially those concerning the temples under review. Goddesses in Java tend to be rather fierce or, at the very least, powerful and unforgiving. (The case of the famous Goddess of the Southern Ocean is one firm example, and we will discuss her shortly.) In Java, the idea of “transgressive sacrality” applies not only to the Indian perspective on examples of ritual marriage, sex in cemeteries, and sacred prostitution, but also to the Islamic perspective; both cultures consider them equally transgressive. It is the third characteristic—identification with a deity—that will give us the most problems in present-day Java, however, since that “deity” should be the God of Islam and identification with that God is normally understood as heresy or blasphemy. Yet, if we redefine “deity” in this instance as referring to other spiritual identities—like that of the Sultan of Yogyakarta in his role as husband of the Goddess of the Southern Ocean—then we may be closer to the mark.

We will not try to fit Javanese mystical or esoteric practices—those falling under our general rubric of “tantroid”—into a pre-formed template, or assume that what we are calling Javanese Tantrism is perfectly consistent with other forms of Tantra. The Javanese spiritual experience is unique, but it does demonstrate influences from other cultures, as we will see from their sacred architecture. In my own personal quest to understand what I call “the technology of spirituality,” I focus more on the practice than the theory without attempting to extrapolate a philosophy or an ideology.

By starting from the body and its functions, I realize that I am in danger of developing a universalist point of view concerning spirituality, but that is a danger I have to accept. We all share the same biology and experience the same biological functions, at least at the basic level of the five senses and the nervous and reproductive systems. When the body is perceived as an instrument in the spiritual toolbox, then we are constrained by its constraints. Altered states of consciousness may be induced through fasting, meditation, or breath control, and we may interpret these states differently, depending on our culture and environment. But the states will be altered and these states will be valued as visions, as communications from spiritual sources, or as evidence of occult powers. The individuals who voluntarily undergo these rigors are the religious specialists of their respective cultures. They may not be the priests or religious hierarchs necessarily, but they will be revered for their direct experience of the Other. By transgressing the normal functions of the body, they also transgress the natural order of the community; they break tabus, they cross over the liminal divide that demarcates safety from danger. To breathe naturally, to eat when hungry, to sleep when tired—these are all natural functions of the human animal and society is arranged around them. To violate these functions—to control breathing through pranayama, for instance, or to fast, to remain awake for days without sleeping—is to break the body's own tabu system and, by extension, the tabu system of the community. The idea of transgression, then, seems to be at the heart of esoteric practice and, in particular, the practice we call Tantra.

There are statements in some Tantric literature that the practices considered the most transgressive and scandalous should not be performed, but rather should be interiorized—i.e., meditated upon in symbolic form only and not “acted out.” The problem with this view is that it is not consistent with orthodox Vedic belief regarding ritual performance, as we have seen. More important, it is virtually impossible to read some of the more blatant Tantric texts—those with a long and distinguished pedigree—and see them as anything other than precise instructions for carrying out these rituals in actual form with living partners. While one may make the argument that, on some plane of understanding, to visualize transgression is the same as acting on that impulse—“committing adultery in the heart”—we may agree that actually committing the transgression in the mundane world while simultaneously visualizing it is to ensure that the transgressive act has been performed on all levels of awareness.

As Tantric scholar Harunaga Isaacson points out, even in the Buddhist form of Tantra:

Having been instructed by the guru what he must do and on what he must concentrate, the initiand, uniting with the consort, must mark that moment of blissful experience that ... offers an at least apparent absence of all duality ... This experience is said to occur in the brief interval between the moment in which the initiand's bodhicitta, that is his semen, is in the center of the mani, that is the glans of the penis, and the moment of emission ...18

There are several important points made in the above excerpt. First, actual sexual union occurs, not merely a symbolic version. Second, emission also occurs (rather than the retention or internalization of the ejaculate). Third, one approaches advaita—the Buddhist sense of non-duality—at the moment of orgasm. And perhaps a fourth point can be made as well: There is a peculiar power in concentration. In fact, without concentration—the single-minded focus of consciousness—the ritual, or any ritual, cannot succeed. Thus mind and body must become fused around a very specific goal, and in order to reach that state, a great deal of preparation must be made that includes training the body as well as the mind.

Twilight Language All things are concealed in all.

Paracelsus, Coelum Philosophorum

One of the essential characteristics of esotericism generally, and of the traditions that come out of Tantra specifically, is the implementation of a special language that is used to conceal and reveal secrets simultaneously. In the Western esoteric tradition, this is called the Language of the Birds or, more commonly today, the Green Language.19 The enigmatic European alchemist Fulcanelli referred to this language as the argotique, a play on the term ars gotique or “Gothic art”—a reference to Gothic architecture, which is widely believed to represent an esoteric tradition written in stone.20 To Fulcanelli, this argot was the means by which alchemists and adepts communicated with each other and selected members of the mundane world who could interpret the symbols. Like a kind of sacred rebus, the messages of the Green Language can be read on different levels of meaning simultaneously, thus concealing sacred mysteries in plain sight. A famous example of this is Chartres Cathedral, whose strange sculptures and carvings have stimulated the imaginations of thousands of visitors and contributed to a cottage industry based in their interpretation.

In India, this sacred language is called sandhya-bhasa, or the “twilight language.”21 The word sandhya is particularly relevant to our case, because it means quite literally the “time of union.” The time of union is considered to be both dawn and dusk—thus the union of night and day. Noon is sometimes also considered a “time of union,” as it is the point where morning meets afternoon. An important Vedic ritual, the sandhya vandanam, is performed thrice daily—at high noon, and when the sun is on the horizon, either at sunrise or sunset. We should note that the sandhya vandanam ritual is focused on the concept of amrita, the nectar of immortality, which is a core element of Tantric ritual in general and which is emphasized at Candi Sukuh and Candi Ceto in Java.

The word bhasa means “language,” so we can interpret sandhya-bhasa as the “language of the time of union,” which has a perfectly Tantric ring. It is interesting that the term sandhya is also taken to mean “perfection,” and is a common girl's name in India. Sandhya is the daughter of Brahma, who created her and then fell in love with her, in the process creating Kama, the god of desire. Thus, as a deity, she is often also considered the wife of Brahma as well as his daughter and, in other texts (like the Siva Purana), the wife of Shiva (which makes her the equivalent of Parvati or Uma). Catherine Benton raises the possibility that we can see this story as a way of understanding the nature of human love and desire.22 It is, she claims, a projection of inner conflicts on an available object, just as Brahma fell in love with his own creation, Sandhya, even as he was aware that she was nothing more than his creation. Desire (Kama) born of this type of conflict is stronger than our conscious understanding, which sees it as ephemeral and perhaps even selfdestructive. Tantra, which addresses desire and love head-on, may be an ancient form of psychotherapy, one in which psychological conflicts are used as energy sources to promote spiritual progress and illumination.

The usual complicated Indian theological structures, therefore, give rise to several possible interpretations of the role of Sandhya in a Tantric context. Throughout the rest of this work, we will focus mainly on her manifestations as Parvati and Uma, with further references to Kali and Durga.

The twilight language is an allegorical word game, with double and triple meanings for each term. For instance, in this language—which, after all, is the language extensively used in the Tantras—the Sanskrit term vajra can mean “thunderbolt,” “power,” linga, “penis,” even shunya (“void”)—all terms cognate with ideas of masculine energy and creative (and destructive) power.23 While this example may seem obvious to a casual reader, the complexity increases with more specific terminology and references. We encounter the same thing in Western alchemical texts, which are replete with terms like “the white eagle,” “the red lion,” etc.—all in a seemingly metallurgical context. In his many works on alchemy, Jung made the claim that these terms had psychological significance, and I make the case that the terminology can be employed as well in metallurgical, chemical, biological, neurological, psychological, and sexual contexts, to name but a few.

The twilight language is employed to convey information about the world. It is a cosmological language and the processes it describes can be understood on a variety of levels, at times interchangeably. What this implies is that an alchemical text can be interpreted as a manual of Tantra just as easily as a Tantric text can be interpreted psychologically. The benefit to researchers is that the Tantric texts are almost blatant in their description of actual sexual processes—processes that have spiritual change and transformation as their purpose. This enables us to apply that interpretation to a variety of other texts in the “twilight” or “green” language. Using these texts to interpret each other suddenly opens up a rich field of information. In actuality, this concept was enshrined in the Vedas from the beginning, since the Vedas are considered thrayi— in other words, statements in the Vedas have three meanings: an exoteric meaning, an esoteric meaning, and a “philosophical” meaning. A parallel case can be seen in alchemical literature, which can have a purely chemical meaning, an inner or psychological or psycho-biological meaning, and a purely spiritual meaning.

One of the ways in which “green” or twilight language is employed is in the field of symbols. In the West, these symbols take the form of the images on tarot cards, the carvings on Gothic cathedrals, and the strange illustrations in books on alchemy, Kabbalah, and magic. Freud understood dream images to represent psychological states, many with a sexual component; Jung codified these symbols even further, finding a structure peopled with mythic ideas and concepts.

In Tantra, these symbols also can be found in architecture. Similar to the way images are used to convey esoteric information on Gothic cathedrals, like the well-known example of Chartres, carvings on Tantric temples are used to suggest various psycho-spiritual states and are illustrative of the means to achieve them. These carvings may be statues of the various deities of the Indian religions—each with specific qualities, aspects, and powers, just as Catholic saints are interpreted in the Afro-Caribbean religions of Santeria and Voudon—or they may be of scenes from the great Indian epics like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, which have as much resonance for an Indian devotee as Biblical stories do for Westerners, with corresponding psychological relevance and depth. Some temples are explicit in sexual terms and depict actual sexual acts and positions. To the non-initiate, these may be interpreted at face value; an initiated view holds that the acts and positions have psycho-spiritual components and refer to altered spiritual states, some of which may be achieved by the application of these very acts and positions.

In Java, the temples of Candi Sukuh and Candi Ceto have the most blatant sexual imagery, as we will see. However, such massive and famous edifices as Borobudur and Prambanan can also be identified as Tantric temples. Borobudur itself has been acknowledged as an example of the Vajrayana Buddhism of Tibet, a Tantric denomination. Other temples and shrines may not boast as much iconography as Candi Sukuh, but they may be utilized as centers of Tantric practice just the same—like the shrine and cemetery at Gunung Kemukus, not far from Candi Sukuh. In this case, the twilight language is employed, not in images or allegorical language per se, but in the performance of ritual (what we may call “twilight action”), where the ritual itself is an allegory—in this case, the peculiar type of temporary marriage that is solemnized at Kemukus. Marriage has been understood allegorically all over the world and in many eras. In 17th-century Europe, we have the Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz, which is considered to be an alchemical allegory. In the Gnostic texts discovered at Nag Hammadi, we read that the Holy of Holies of Solomon's Temple was interpreted as a bridal chamber. We will look at these examples in the last section of this work.

The Schools of Tantra There are two main and distinct “schools” of Hindu Tantra, the Shiva and the Shakti schools. The Shiva school obviously places Shiva in the position of the High God and the focus is on him, with a somewhat lesser emphasis on his consort, Shakti. In the Shakti sects, however, this polarity is reversed, with the emphasis placed on the feminine aspect of the two. Both Shiva and Shakti represent forms of power, but Shakti is power by definition. Shiva is understood as the principle that directs this power, but it is Shakti who personifies the type of occult, esoteric force that is at the heart of the practices we call Tantra. During the course of this study, we may have occasion to refer to these differences from time to time, so it is wise to point them out now.

It is entirely possible that the first form of Tantra was Shakti in nature. An epigraphic reference to the Matrikas— the seven Mothers—that dates from 423 CE may be the earliest known Tantric mention anywhere.24 According to the Devi-Mahatmya, a sixth-century CE Shakta text, the Matrikas are fierce goddesses who were summoned by Durga to help her in a battle with demons. They are the female forms of male deities, and are sometimes confused with the ten Mahavidyas, who are, themselves, rather frightening in appearance and who have some odd preferences (sex with corpses, a goddess who cuts off her own head, etc.).25

As mentioned, fierce goddesses are a staple of Tantric practice. The most famous of these is Kali, who is often depicted with a lolling red tongue, a necklace of human skulls, various weapons, and a skull cup full of human blood. Kali is in her element in a charnel ground or cemetery. She can sometimes be seen standing on the prone body of Shiva. In this manifestation, she can be interpreted as energy or power, without which Shiva is helpless.

The cult of Kali represents a Shakti version of Tantra, with its emphasis on the feminine as the dominant and supreme deity. Other forms of the fierce feminine include Durga—whom we will come across in Java—and Chinnamasta, the goddess who cuts off her own head. Even Tara, the gentle goddess of Tibetan Buddhism, is a blood-thirsty deity in the Hindu tradition.26 In India, Tara resides in the cremation ground and is often depicted standing on a corpse, virtually identical in every respect to Kali. Blood sacrifices are made to her by her devotees.

We may well ask why it is that a belief system that holds the feminine to be the supreme deity would depict its goddess in this brutal, bloody, and altogether hideous fashion. We should remember that these goddesses are also often described as lustful, even rapacious. Are these stereotypically male qualities, projected onto a female object of adoration, meant to legitimize male tendencies toward the violent in death and sex? Is it a kind of Zen koan, requiring devotees to make a leap of consciousness from the idea of a nurturing, wholesome feminine to this outrageous caricature of death and destruction, putting two contradictory images side by side and forcing a psychic resolution?

Perhaps there is another way to understand the wrathful and bestial goddesses of Tantra. Kali and the Hindu Tara are both shown standing on motionless, prone corpses of men. Often, these are understood to represent Shiva, and sometimes the corpse is shown with an erect penis. We know that the principle of Shakti—psycho-spiritual power, or cosmic power, depending on how you interpret it—is feminine. A prone Shiva, a corpse-like Shiva, may imply a post-orgasmic Shiva and the image of Kali or Tara standing over him may signify the release of that energy. Why, then, the accompanying images of death?27 Why the worship in a cremation ground?

How are sex and death related, particularly in the context of Tantric practice? This is a question to which we will return as we investigate some of the tantroid practices we will encounter in the mountains of Java.

Excursus: A Brief Summary of Indonesian History Many readers who are familiar with Asian religions and knowledgeable about the cultures and histories of India and China may remain relatively unsure about Indonesia and its history and religious traditions. Because this history is so important to any intelligent discussion of Tantra in Java, it is necessary to offer a very brief summary of the subject before devoting ourselves to an investigation of Javanese mysticism itself.

The Javanese Dynasties Indonesia is the name given to a huge territory in Southeast Asia that stretches across three time zones along the equator. It has the fourth-largest population in the world after China, India, and the United States. It is also the largest Muslim country in the world, with over 200 million citizens professing the Islamic faith. It consists of more than 17,000 separate islands, of which Java is the largest.

Since the nation's independence from the Dutch after World War II, the Javanese have dominated Indonesian government, culture, and politics. As the largest ethnic group, their language and customs have influenced the development of all that we think of as “typically Indonesian.” We must remember, however, that “Indonesia” as a concept did not exist until about the 1920s, when the independence movement began. Until then, Indonesia had been colonized by a succession of Asian and European powers.

We will not attempt a comprehensive account of Indonesian history, as colorful as it is with its tales of sultans and monks, colonialists and traders, Arab sailors and Chinese Buddhists. Much of what we know of early Indonesian history, however, comes to us (with some notable exceptions) from its foreign visitors. Manuscripts in Java and Sumatra were written on palm leaves and so were prone to early destruction and decay. It is, however, safe to say that the first Indonesian kingdoms of which we have any information are those that have their origins in India and elsewhere in Southeast Asia. The earliest, the kingdom of Tarumanagara, lasted from 358 to 669 CE and was located in the northwestern part of Java, near present-day Jakarta, in the Sundanese region. This was a Hindu kingdom, as epigraphic and other evidence—including some Chinese sources—attest. The earliest surviving written records in Java are stone inscriptions in Sanskrit using the Pallawa script, which is a form of writing that originated in the Tamil Nadu area of southern India. Thus, we can safely say that Hinduism was present in Java from at least the fourth century CE.

The Srivijaya empire, based in Sumatra with its center in Palembang, began in the late seventh century CE. It continued on through the 13th century and had a significant influence not only in Java, but also in the Malay peninsula, Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Oddly, very little remains of this once-powerful kingdom, which was not even known to have existed until foreign scholars began to uncover evidence of it in the 1920s. It, too, was heavily influenced by Indian religious traditions and was a veritable intellectual center of Vajrayana Buddhism by the seventh century.

Chinese Buddhist scholars went to Sumatra to study and, as we mentioned at the beginning of this book, the famous Buddhist teacher and saint Atisha lived in the Srivijayan kingdom for some years before bringing Vajrayana (Tantra) teachings back to India and Tibet. There is some debate as to where Atisha actually wound up, however, for by that time—the 11th century CE—Srivijaya extended to Java as well as to what is present-day Borneo, and its capital moved to Java for a period of time during the eighth century, when the massive Buddhist edifice at Borobudur was built. Another problem in locating important geographical sites lies in the ease with which foreign travelers and armchair tourists writing 1000 years ago used terminology and place names with only the barest first-hand knowledge of what they were talking about. Thus, there is some confusion as to the precise location of Srivijaya at certain critical periods in its history.

Other kingdoms existed alongside the Srivijayan empire, including the Sailendra and Sunda kingdoms as well as the famous Mataram kingdom. The Sailendra dynasty is often associated with Srivijaya for a variety of reasons, including the intermarriage of its rulers. Thus some scholars attribute the building of Borobudur to the Sailendras themselves. It is interesting that the earliest record of the Sailendras is a stone inscription that mentions the erection of a shrine to the goddess Tara that dates to 778 CE. The Sailendras, however, seem to have disappeared in the ninth century shortly after the completion of Borobudur and their defeat by a ruler from the short-lived Sanjaya dynasty who later moved back to Sumatra. In fact, there is still some debate as to whether the Sailendras were really Buddhists or Hindus—or both.

The Sunda kingdom, as its name implies, was located in western Java in the area now known by the same name. It represents one of the longest and most continuous of the Javanese regimes, lasting from 669 to 1579 CE. This also was a mixed Buddhist and Hindu kingdom, but with a strong element of indigenous (“animist” or “shamanistic”) practices as well. Unlike the still somewhat mysterious Srivijaya and Sailendra cultures, the Sundanese have kept the memory of their greatness alive in a strong oral tradition that has passed down historical information—as well as its indigenous, pre-Buddhist beliefs and practices—through the centuries.

The Mataram kingdom (not to be confused with the Islamic Mataram Sultanate of the 13th to 16th centuries) lasted from the eighth to the 11th century CE, and its power centers were in present-day Yogyakarta and Surakarta (Solo). Some scholars attribute the origins of this dynasty to the Sanjayas, while others claim that the building of Borobudur and the equally impressive Hindu complex at Prambanan occurred thanks to the Mataram kings. In the 10th century, or possibly earlier, the kingdom moved its capital farther east to Central Java. This was possibly due to an eruption of Mount Merapi at that time that covered Borobudur in volcanic ash from which it was only rescued in the 19th century.

Perhaps the single most important dynasty—in terms of both our subject and of Indonesia as a whole—was the Majapahit kingdom, which lasted from 1293 to 1500 and disappeared with the ascension of Islam in the archipelago. Prior to the Majapahit, there were several other dynasties of greater or lesser importance, the most notable of which was the Singhasari kingdom (1222–1292) that gave rise to the Majapahit, and the Kediri kingdom (1045–1221) in Java, which was ruled by a series of kings who considered themselves incarnations of Hindu gods like Vishnu and Ganesha. The second king of Kediri was believed to be the incarnation of Kamajaya, the God of Love known in Sanskrit as Kamadeva; his queen was believed to be Kamaratih, the Goddess of Lust and Passion known in Sanskrit as Rati. Thus it can be seen that the Hindu religious tradition was quite strong in Java and remained that way until the advent of Islam.

By this time, the stresses imposed by foreign visitors and alien cultures was already beginning to strain the Javanese worldview. Java is an island, and the trade along its coasts was brisk, with ships arriving from India and all of Asia regularly. The entire Malay and Indonesian archipelago was famous worldwide for gold and spices. Muslim traders from India and other countries brought, not only their wares to sell, but also their religion. Slowly, Islam began making inroads from the coastal communities to deeper within the interior where the great Javanese palaces and temples were located. The riches and influence of the Javanese kingdoms were so well-known that the great Mongol emperor and warlord Kublai Khan (a contemporary of Marco Polo) sent an army of more than 20,000 troops to attack them, but was defeated in 1292 by forces under what would become the Majapahit dynasty.

Oddly enough, it was Dutch perfidy that almost lost the world the historical texts that revealed the existence of this magnificent kingdom—and a Dutch official who saved the texts from the flames. The story is illustrative of the how the people of Indonesia had lost virtually all memory of their greatness before the arrival of the colonial powers, save for legends passed down from generation to generation and, of course, the mute but insistent testimony of the stones—the temples, monuments, petroglyphs, and other artifacts found everywhere on the islands. The manuscript in question is the Deshawarnana, perhaps better known as the Nagarakrtagama, written in 1365 as a description of the court of Hayam Wuruk, Majapahit's most famous king, who reigned from 1350 to 1389. In the year 1894, the Dutch sent a small army to raze the palace of a ruler on the island of Lombok. Among the priceless treasures that were nearly consigned to the flames were the only written records known of the Majapahit empire. They were saved by an official attached to the Dutch expedition.

However, there was another text that was preserved as well. A set of six copper plates roughly the size of an A4 sheet of paper (or about 8” × 12”) were discovered buried in the ground in East Java in the year 1780. Luckily, the inscribed plates were copied onto manuscript, because the originals were lost and never seen again. The copy itself disappeared, until it was rediscovered in 1888 in Leiden. Thus it was not until 1888 that the world learned how Majapahit came to be, for the copper plates told the story of its founder, King Wijaya. The manuscript from Lombok told the story of Hayam Wuruk. From these two core documents we have been able to piece together the history of this empire, assisted by an ever-growing body of other evidence, some of it from Chinese and other foreign sources who had been visiting Java and trading with it during that period.

All available evidence describes Majapahit as an empire that embraced the diverse religious and cultural interests of its people. Both Hindu—in this case, Shiva worshippers—and Buddhist leaders lived at the palace, and indigenous religious leaders also enjoyed a great deal of autonomy. Vishnu worshippers were also in attendance during this period, although their influence at the court was not as great as that of the Shiva cult. During this period, we can see that Hindu and Buddhist deities were identified with local Javanese gods and goddesses, and the Javanese belief system was brought into line with Hindu and Buddhist practices—or vice versa. Also, Hayam Wuruk claimed the title of chakravartin, a peculiarly Indian title that means “the one through whom the wheel of Dharma turns.” The implication, of course, is that the political ruler of the kingdom was also its spiritual leader, in the sense that he or she embodied the soul of the country and was the channel for the Dharma. Depending on the context, Dharma can mean the Law (as in religious law, analogous to the Torah for the Jews), or duty in the sense of spiritual responsibility. Both Buddhists and Hindus use the term, albeit with slightly different connotations. For those who live in accordance with the Dharma, life proceeds as it should; if a king rules in accordance with the Dharma, the entire nation prospers. In this way, it is also similar to the Chinese concept of the Dao.

There was more to regal authority than adherence to the Way, however. Power was also a prerequisite and, in the Majapahit empire—as in the previous Indianstyle empires of Java and Sumatra—power was shakti. We must remember that these were Tantric kingdoms, whether nominally Buddhist or Hindu. The rituals, temples, and statuary all attest to a Tantric view of the world. Indonesia was so important to the preservation and transmission of Tantric doctrine and methods that one of Tibet's three most important teachers, the aforementioned Atisha, came to the Srivijayan kingdom to learn its teachings first-hand. Tantra fit in well with the indigenous spiritual beliefs of a people who identified themselves with the land: its volcanoes, its rugged coastline, its rice and tea fields, its breathtaking interior. Sexual prowess was respected as a manifestation of shakti, and a king was expected to have an abundance of it. The king was expected to be fertile, for that meant the land would be fertile.

Sexual activity was also one way to obtain and direct power; mystic sexual union enveloped partners in cosmic energy and increased their power.28

In other words, this concept was not restricted to those who had a religious vocation. It was not the sole province of monks or ascetics. Tantra was practiced by monarchs in ancient Java and, to a certain extent, still is.

In Javanese Tantric Buddhism there were three methods: mantra, the repetition of a formula endless times; yantra, a magical symbol which had to be drawn correctly; and Tara, energy possessing goddesses. Rituals, magic circles and diagrams, drunkenness, sexual union with a “Tara” and sacrifices of animals and even human beings were common to Javanese Tantric ritual ...29

The question of human sacrifice in Java is a controversial one. Human remains have been found at some temple sites, buried beneath the stones. The practice of human sacrifice as a ritual during the construction of an especially important building is one of which both circumstantial as well as some textual evidence exists, and in fact it is believed to have continued to this day in some parts of Asia.30

That a king should be so intimately involved with these seemingly bizarre practices may surprise those who have come to Tantra through the New Age, which usually frames Tantra in a personal way, as an individual's approach to a kind of spiritual ecstasy through sex. On the contrary, Tantra is first and foremost about power, shakti; those in society who are most concerned with getting power and keeping it are its rulers. Ronald M. Davidson has emphasized this aspect of Tantra, what he calls its “imperial metaphor,” which revolves around the consecration of a king and, by extension, the exercise of royal power.31 If we accept this as true, then it should come as no surprise that an actual king would see in Tantric practice rituals of legitimacy and the assurance of continued power.

The mindset of a Tantric practitioner is such that he or she enters a realm where identification with a deity is required, at least during the course of the ritual. In the mundane world, kings occupy that sort of position as intermediaries between heaven and earth, and the Tantrika aspires to a similar state. That is one of the reasons why Tantra was considered such a threat to the established order. It wasn't due only to their antinomian practices and beliefs, but the idea that a Tantrika, of whatever caste—whatever position in society or even a total outcaste, a Dalit—could, through brute force it would seem, aquire direct contact with the divine forces that inform the monarchy and, by extension, the kingdom. Such a feat put the Tantrika on a par with the king.

In Java, however, the rulers dominated this type of activity for at least 1000 years—from the earliest beginnings of Indian religion in Java to the advent of Islam, and beyond. The people themselves had their own avenues to spiritual power, of course. Those who did not follow either the Buddhist or Hindu Tantric path could avail themselves of their indigenous methods and beliefs. During the Majapahit era, Buddhism, Shaivism (Shiva worshippers), Vaisnavism (Vishnu worshippers), and the indigenous faith all had their place at the court assured. There were, however, other personalities and cults in Java that did not necessarily enjoy the privileges of the court. Today, they would be considered “animists” or “shamans,” but neither of these antique designations really communicates the genuine nature of these individuals and groups. Their rituals, their sacred spaces, their deities all changed with the territory. In Java, it seems that every mountain is sacred; every volcano is an axis mundi. There were (and are) spirits of the forests, of the rivers, of the mountains, of the fields, and of the sea. Sometimes, these take on human, or humanoid, form; at other times, they are perceived as snakes, monkeys, or other fauna. A seemingly innocent scene of a young woman walking alone down a road under a full moon can take on a hideous aspect, for that woman may not be a woman at all, but a fierce goddess, a Durga, or some other dangerous local spirit.

In Java today, you will find all of these beliefs represented, along with Islam and elements of Christianity and even Theosophy. The development of a truly unique form of mysticism is still taking place on the island, one that has accepted the best parts of all traditions—local and foreign—to create a methodology, a program of action, and what we may call “active spirituality” that is peculiar to Java. While African religions survived in somewhat different form among the slave populations of the Caribbean (for instance) and became today's Voudon, Santeria, Candomble, and Palo Mayombe, these are still essentially African religions that adopted a veneer of Catholicism. They were never truly “syncretic,” as has been supposed. The Javanese, on the other hand, remained connected to their land even during long centuries of colonial interference and rule. Their very lives depend on maintaining a harmonious relationship with their environment, troubled as it is with dangerous volcanoes and monsoons. They never lost that connection and, with each succeeding wave of immigrant and colonist, invader and trader, they seem to have incorporated whatever seemed consistent with their own needs and beliefs. Even today, the slogan of the New Order in Indonesia is “Unity in Diversity” and, although there have been attempts by special interests to impose a unity upon the diversity, Indonesia has remained committed to maintaining its own unique culture while simultaneously embracing Islam, modernization, and democracy.

The Coming of Islam The Majapahit dynasty was the last “Indian” kingdom in Java, and the last purely Tantric one. Tantra survived beneath the Islamic surface of its sultanates and managed to become absorbed to some extent in cultural practices and beliefs, as we shall see. As a formal recognized practice, it was never really suppressed or denied. This may be due to the fact that Sufism, the strain of Islamic teaching and influence that first came to Java, was itself mystical in origin. It was perhaps this confrontation of Tantra and Sufism that allowed the growth of what is known today as kebatinan, a peculiarly Javanese form of mysticism.

The origins of Sufism, like the origins of Tantra, are shrouded in mystery. Traditionally, Sufism is considered the secret or esoteric side of Islam that was taught by the Prophet to his disciples. Thus it may be considered a form of Islamic Gnosticism. The outer form of Islam is called lahir; its inner, or esoteric form is known as batin. This Arabic word has given us the Javanese term kebatinan. One of the central practices of Sufism—the constant repetition of the name of God—is called dhikr in Arabic. Its parallel with the Indian practice of mantra is obvious. It is believed that the constant repetition of the name of God will bring one into a state of spiritual ecstasy. Since the practice of mantra was well-known to the Javanese for a millennium, it is assumed that, when the Sufi sheikhs arrived with their version, it was readily understood in an Indian and Javanese context.

More important, just as Tantra was sometimes seen as an unorthodox form of Vedic Brahmanism, so Sufism was regarded with suspicion or even disdain by many orthodox Muslims. Vedic Hinduism is a community-centered, socially structured religion with a rigid sense of cosmic order and a requirement for adherence to the rules and outer forms of the faith. Tantra represents an individualistic alternative. Moreover, it is an alternative that emphasizes personal enlightenment and the acquisition of mystical powers, neither of which is normative to Vedic teaching. Sufism also emphasizes personal—one may say private—spiritual experience in the greater context of Islam which, like Vedic Brahmanism, requires adherence to the rules and the outer form of the religion.

Islam first arrived in Java around the 13th century, and was largely confined to the coastal communities where trading was done. The first Islamic sultanate in what is now Indonesia was located in North Maluku, an island far to the northeast of Java that was a center of the spice trade, particularly in cloves. The Sultanate of Ternate (as it was known) was established in the year 1257 and, remarkably, is extant still as an important cultural influence, although without any political power. Closer to home, we find the Sultanate of Demak on the north coast of Java (c. 1475–1548); the Sultanate of Banten on the northwest coast of Java, where it was a center for the trade in pepper (1526–1813); the Sultanate of Aceh, established in 1496 at the far western end of Sumatra, which lasted until the early years of the 20th century; and, finally, the great Mataram Sultanate that was founded at about the same time and that prospered until the coming of the European powers in the 18th century.

It is easy to see that the arrival of Islam in Indonesia was assisted by the trade in spices and gold. Ships arrived from India and the Middle East, through the Straits of Melaka and the Sunda Strait (between Java and Sumatra), seeking goods at ports mostly along the western and northern coasts of Java, which were also centers of first Hindu and Buddhist, and then Islamic learning. While the sultanates did not appear until the mid-13th century at the earliest, Islam was already in evidence in a casual way at least 100 years earlier. It was only the strength of the Majapahit empire that kept Islam from dominating the entire region until the early 16th century.

The Colonialists In the 16th century, the mighty naval forces of Spain and Portugal began to extend their reach into the New World and Asia. Spain established colonies in Florida, the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America, while Portugal took possession of Brazil. At the same time, these two countries fought for dominance in Southeast Asia. When the dust had settled, Spain had control over the Philippines, while Portugal held important ports in what is now Malaysia and Indonesia.

The Sultanate of Melaka (Malacca) was first on the list. Melaka is a city in what is now Malaysia, on the west coast of the peninsula and across the Straits of Melaka from the Indonesian island of Sumatra. Melaka was largely inhabited by Malays and Chinese (the so-called Straits Chinese). Around 1400 ce, it became a sultanate that lasted until the Portuguese came and invaded the territory in 1512. The Portuguese remained a force in the area until the mid-19th century, with an Asian empire that included Taiwan (Formosa) and the Chinese port city of Macau (which only recently was returned to Chinese sovereignty).