The Development Of Shamanism In Mongolia After Socialism by Tuvshintugs Dorj

Editor’s introduction: Tuggi Dorj, as he is commonly known, is a devout and serious practicing royal Mongolian shaman. He maintains a widespread humanitarian practice of shamanic trance consultation as well as a deep knowledge of and commitment to the practice of esoteric ancestral Mongolian shamanism, including through his organized association with other Mongolian shamans. In his contribution here, Tuggi reveals the depths of difficulty and cultural loss that afflicted shamanism during the Manchu and then the Soviet-dominated socialist periods and major aspects of shamanic revival in Mongolia since the early 1990s.

Today, shamanism is a widespread and even acclaimed popular culture feature of urban as well as rural life in Mongolia. In the process, as Tuggi Dorj discusses, Mongolian shamanism faces challenges as well as potentials, including uninformed practices of so-called shamanism that are undertaken as money-making schemes rather than for social good and broader well-being. The importance of recouping dwindling ancestral cultural knowledge concerning Mongolian shamanism is thrown into relief by the significant contributions of alternative shamanic consciousness and of strong personal and shared cultural harmony with the social, spiritual, and natural environment.

As Tuggi Dorj delineates, Mongolian shamanism evokes a rich and barely-tapped store of astrological, environmental, and geographic cultural knowledge, including in relation to the personal and social well-being of Mongolians. Importantly, Tuggi is a strong advocate of scientific research and technological study such as neuroscience to document and verify the powers and potentials of ancestrally transmitted Mongolian shamanism. In the process, he hopes, the positive human potential of Mongolian shamanism can be fully identified and made public for the benefit of humanity.

For much of the last century and a half, Mongolian shamanism has been restricted and its benefits denied. During the socialist era, religion was intentionally propagandized to the people as a poisonous and defiant activity. Even before this, however, during the late nineteenth, century, Manchu dynasty policies spread Lamaism in Mongolia and recruited Mongolians to Lamaism—with the larger intention to weaken Mongolian resolve to fight and rebel against Manchu rule. Due to this influence, Mongolian traditional shamanism was gradually weakened and largely forgotten, along with practices of worshiping heaven, respecting the elderly, commitment to abide by one’s oaths, and the spirit and power of fighting together to fulfill heavenly destiny. Though shamanism had been actively practiced and its world view believed by many Mongolian tribes and peoples, its traditional ideology, ritual, and knowledge were greatly weakened. Though there have been some written sources of shamanic tradition and rituals, these were not retained or handed down with proper secrecy within groups in subsequent generations, including by takhilch, tugch and suldech tribes or by royal kinship. Consequently, shamanism as traditionally informed had all but vanished. Some recordings and sources about shamanism had the following inaccuracies, including during the socialist period of Soviet domination:

- 1. Shamanism was viewed and explained from the viewpoint of ordinary persons rather than from the perspective of the shaman

- 2. Basic shamanic meanings were modified to be consistent with socialist era order and political interests

- 3. Shamanism was defined to fit within the interests of Buddhism

The traditional meaning and rituals of the shamanism were degraded and turned into shamanism as associated with certain Buddhist rituals. By adopting Buddhist rituals, Khalkh Mongol’s yellow shamans tried to show more power than authentic black shamans. Due to this propaganda, shamanism was defined in a narrow framework, its meaning was changed, and its scope reduced. Consequently, traditional shamanism was practiced by only a few tribes. Shamanism had only been practiced as a developed tradition for 300-400 years in Mongolia by the beginning of the socialist period, and together with Buddhism, it fell under socialist repression. Along with Buddhist monks, many shamans were detained and sentenced to jail during this time, though, in contrast to the monks, few shamans were actually killed. Because shamans at that time lived primarily in remote rural places, their overall social influence was weak, and they had almost no power or wealth. Partly as a result of this, most shamans received “only” 5-10 year jail sentences during the socialist purges. Nevertheless, Mongolian shamanism has for centuries been inherited from generation to generation through domestic teaching and transmission, and I am one of the shamans who inherited shamanism in this way.

Below are some case studies of the histories and challenges faced by shamans who have received traditionally inherited shamanic power and practices in Mongolia.

Shaman Chur received a ten year jail sentence during the socialist period in Selenge aimag. Just before his arrest, he put his drum and costume in the river Uuriin, as a sign of becoming an ordinary man, though he kept his mirror and khuur (a Mongolian traditional musical instrument used to call shaman spirit). He never performed shaman rituals again. His mirror and khuur are kept by his son Khuushaan in Erdenet city. His two grandchildren became shamans and are holding their family shamanic spirit.

Shaman Choi (Choikhuu) was arrested and jailed together with shaman Chur by one decree and died due to the illness on his way home after finishing his jail sentence. He put his shamanic belongings in the mountain, and his mirror (toli-specially made silver or golden, round shaped accessory of shaman), khuur, seter, khiimori and khadag (specially made band of silk) were left to his children. Now his grandchildren hold their family shaman spirit and continue their family shaman rituals.

Khukh gol’s soyod Uriankhai shaman Luvsandorj’s children have also recently received their family shaman spirit and continue to practice shamanic rituals. Norjmaa, who came from Eg-Uul as a bride and became Khos’s Shaman’s disciple, was also arrested and sentenced. After completing her jail sentence, she never performed shaman rituals again; nonetheless, she continued to help people until the end of her life. She had no children, so her niece received the family shaman spirit five or six years ago, and she is continuing the shaman rituals.

Shaman Khuukhenjii was Darkhad’s uyalgan. She came to Tsagaan-Uur as a bride and passed away in 2009. She helped Tsagaan-Uur’s people by performing shaman rituals. Buryat people who came from Russia settled down in Tsagaan-Uur sum. Later their descendants followed Buddhist religious practice and studied Buddhism in Ikh Khuree.

Other examples include Ravjaa lama’s descendants, who revived Udval shamanic rituals and are continuing them. Shaman Namjilmaa, descendant of shaman Joovon of Chandmani-Undur sum’s Khalkhyn khairkhan, received family shaman spirit and has been performing shamanic rituals for three years.

In this way, shamanism, which had been hidden and almost forgotten during the socialist period, is now reviving again. Descendants of shamans are receiving their family shaman spirit. However, most of these shaman descendants weren’t able to directly inherit shamanic knowledge from their predecessors. Many of them have only seen or heard about shamanic rituals, and there are few traditionally trained shamans who can teach and advise them. This poses difficulties in properly reviving old traditions and rituals of family shamanism.

Although shamans are trying to revive shamanic rituals by asking about them from elderly persons who may have seen or heard about them, much of the relevant knowledge has been forgotten. Moreover, research materials and works about shaman rituals are very rare, and those existing try to explain shamanism rather than providing a practical training guide. Current geographical and astronomical terms and names are different from the old names of heavens (tenger), gods, and local deities; therefore, it is difficult to re-establish their previous names and associated meanings. Although some texts explains methods and timing for deifying mountains, hills, rivers, lakes, and so on, written largely by knowledgeable monks of that time it is difficult to locate and access these materials, as most of them are either lost or still being hidden. Those few exceptions are written in Tibetan and Sanskrit languages, so we face difficulties in translating these into contemporary Mongolian language. Today people and youths can easily obtain and analyze information and knowledge once it has been made available. Now it is time to make more accessible this information, excepting only the portions of proprietary information that is properly restricted and needs to be kept secret. This will also allow aspects of Mongolian shamanism to be considered or explained on the basis of scientific or philosophical examination.

At larger issue is our ability under present conditions to find proper ways of living in harmony with nature. I believe that religions generally connect with universal meaning, the nature of humanity and of the world around us, the influence of ancient science, and desire to find true knowledge of life. The main differences between the religions appear to be their respective ways and method of propagating information and knowledge. Given Mongolia’s history, however, these differences have become particularly complicated, and the earlier forms of shamanism clouded, due to social policies and political influences.

Shamanism is generally accepted by scholars to be the first and most fundamental form of human religion in historic and evolutionary terms. In this sense, shamanism is the ancestral origin or base of all religions. It is also arguably the most democratic, equitable, and, in its own way, scientific religion. Even when the state and society were punishing Mongolians and prohibiting their religion, shamanism was not erased during either the Manchu Dynasty or the Autonomous and Socialist periods. Even during these times, there is some evidence that shamans helped resolve social and religious issues by the means of discussion. Back in those times, shamans lived in their rural homesteads, helped other people by performing ceremonies during the evening and at night, and taught shamanic knowledge and rituals to their children. Although children grew up watching and listening to what they had been taught, they performed shamanic activities only rarely due to urbanization, work, society, and fear of stigma or reprisal.

During 1924-1930, when Mongolia was politically independent, shamans openly performed religious rituals. Even today some places near Ulaanbaatar city have shaman ames. Though shamans were oppressed, jailed, and driven into hiding from 1930 until the end of the 1950’s, shamanic rituals were still privately practiced in rural areas. But new generations of youths, raised and socialized from 1960 through the middle of the 1980’s, avoided and were afraid of talking about shamanism and other religions. Consequently, this religious tradition and its knowledge have been at risk.

Under the Soviets, including their interest in ethnographic documentation, Mongolian researchers studied shamanism from 1950 to 1980 and gained significant information, as many shamans were alive at the time. However, due to social influence and political pressure, final drafts of research on shamanism were written from the limited perspective of ethnicity and myth, and they tended to adopt one-sided conclusions that denied the contemporary value and ongoing significance of shamanism. Consequently, during the socialist period, shamanism was viewed from a scientific point of view as a set of archaic linguistic and ethnic rituals. In real life, however, shamanism was secretly practiced among relatives and local people. From the standpoint of Mongolian society as a whole, however, shamanism was viewed as a backward relic of the past and as an ideology against law, science and proper social consciousness.

Shamanism after the Socialist Period

Since 1990 shamanism has been more actively and openly discussed among Mongolians. Scholars have begun more sensitive research on shamanism and on the descendants of shamans. Moreover, with the increasing modern need to live in harmony with tradition, state, and nature, and given the gradual revival of the shamanism, information on and knowledge of shamanism has started to be gathered from those who had kept their knowledge and traditions private. This information is now spreading to more and more people. [Indeed, shamanism has now become a very widespread public and urban as well a rural practice in Mongolia today.]

After receiving advice from the elderly and consulting about the exact time and place for auspicious practice, knowledgeable and powerful shamans now practice in Mongolia based on knowledge and ritual obtained through home schooling and other training. The Mongolian “Organization of Shamanism” was established in 1995. This association has been important for providing accurate information and indicating the best exact periods of shamanic practice. The organization has provided a great opportunity for those wishing to inherit shaman knowledge to unite with those few shamans who kept ancestral knowledge and tradition.

At the same time, significant challenges to shamanism have also emerged. These include the use of shamanic “fascination” as a money-making tool, including as expressed by performing magic or giving away secret knowledge. This tendency and its misinformation have spread especially since 2002, when some of the last persons who had inherited detailed shaman knowledge passed away. Consequently, the character, tradition, and rituals of shamanism have frequently been changed, and blind faith in shamanism has become popular.

Most of the written resources that are used by contemporary shamans were produced during the socialist period. Scientific features of shamanism include astronomy, ecology, anthropology, mathematics, music, psychology, and the study of spirituality and hidden consciousness. Nowadays, however, basic knowledge of shamanism is not fully inherited by a new generation, so wrong understanding and blind faith are widespread. Moreover, shamanism loses its fundamental meaning when people believe only superficially in its mystical character, or, alternatively, when it becomes just an object of spiritual study [rather than an embodied practice].

The shaman’s spirit is the main channel for obtaining information about the activity that he or she is going to do. In addition, it should correctly define the object, time, power, and method of shamanic practice and should protect, connect, and support or “own” ulaach (the shaman’s person) by its own power. For example, in order to deify Bat’s family home, fireplace, mettle and drum, first of all, the shaman should identify Bat’s heaven of fortune (birth zodiac), heaven of soul, and heaven of fire that keeps his family fireplace. Secondly, the shaman should find the time, place, and method of deifying these heavens. Finally, being guarded by his or her own shaman spirit, the shaman should perform shaman ritual to connect the family with its fireplace’s spirit. However, as a result of losing and forgetting the main aspects of knowledge, ritual, and tradition, new shamans may use shamanism for unpleasant purposes. Due to forgotten or misinterpreted information, people are only paying attention to the world of spirits and often imagining shamanism based on the small pieces of information that have been received from spirits. These lead to delusions about shamanism. If we worship shamanism in its correct way on the basis of viewing heaven, human, and land as a whole, and gaining correct information shamanism will help us to protect our world.

The existence of heaven causes the existence of earth. The existence of heaven and earth cause the existence of humans, the state, and society. When humans and human consciousness exists, spirit also exists together with them. Understanding the correspondence, coherence, and mutual influence between these and the appropriate way of using this understanding in our lives, in our state and society, and in the world – is called heaven worshipping shaman religion. How we should solve the contemporary problems of Mongolian shamanism? How we should keep and inherit traditional knowledge? How we should explore and find the possible limit of the shamanism?

Science

It is important to study the possibility of justifying, confirming, and testing shamanic knowledge by using scientific methods and technology. Firstly, the limit of concentration and capacities of intelligence need to be defined using the most suitable, simple, and accessible methods and technologies. Possible absolute baselines or benchmarks and their margins [maximum extent, or range of variation] need to be defined on the basis of technology. Secondly, there is a need to study the power and possibility of concentration, of the spiritual energy of shamans who attain a benchmark margin. Thirdly, there is need to study the power and duration of the influence of shamans and their spirits during their ritual performances. Fourthly, there is need to study and find the period of temporal synchronization during the shaman’s ritual of deifying heaven, earth, water and time of stars,’ seasons,’ and nature’s activation and the mutual influence of these, including their influence on people.

Except for science, which makes conclusions based on evidence and proof, it is difficult to conduct a thorough study or make a complete confirmation of the workings of shamanism, including the defining of norms and normative benchmarks. Ultimately, however, the following will become possible:

- 1. For those who want to live properly, it will open the way and method of charging and educating oneself by one’s own possibility.

- 2. It will become possible to preserve and inherit true shamanism by reviving its main characters. Science can help correct the wrong understanding, imagination, and development of shamanic possibilities among people.

- 3. Major achievements of shamanic practice will step forward and contribute to the scientific knowledge of humanity and will guide people to find the correct and more direct way of living in harmony with nature.

- 4. Our awareness will help those people who cannot or who are not destined to become a shaman from being cheated, confused and from losing their time, money, and health.

Facing problems and possible solutions

First, we need to restore shamanic information and knowledge concerning the names, location, direction, and origin of stars and heavens. The understanding of the heavens in shaman religion includes:

- 1. Spirits and ongo takhilga of our ancestors, royalties, and well known Mongolians who went to the heavens

- 2. The highest basis, cycle, universe, space, and highest idol of gaining the main information of shaman religion

- 3. Shamanism has independent names for stars and heavens

Of the heavens, most people know only about Big Dipper, the North Star, Morning Star, Evening Star, the location of sun and moon, and their practices of heavenly oblation, incense, offering, and so on. Very few people have general knowledge about the thirty-three heavens, eight planets, deifying of the sun and moon, or the names and times of deifying ceremonies. Indeed, the location of some heavens, and the time of their activation, is still unclear.

To remedy this situation, we are actively investigating and conducting research. It is necessary to gather information by going to places where shamanic traditions are well preserved and by meeting with elderly shamans and researchers. Moreover, we can restore some information through the comparison method. It is possible to confirm periods of synchronization of stars’ and zodiacs’ activation time, and the time of deifying ceremony, by comparing newly found names and locations with scientific terms. Furthermore, we should meet with ordinary herdsmen and document their knowledge and information about names, locations, directions and knowledge of influences and time so that we can restore lost information and knowledge. Final conclusions and results should be scientifically documented and verified as fully as possible and should be properly presented to the world at large for the sake of humanity.

In addition, we need to take multiple measures and conduct activities of translation and historical derivation. For instance, terms recorded in Buddhist scriptures need to be studied and compared with sources from the outside that were later translated into Tibetan and Sanskrit.

Conclusion

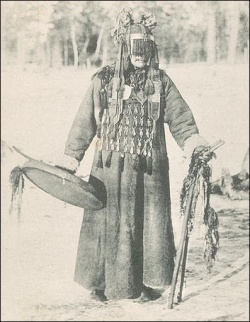

As a nation, Mongolians, who worshiped heaven and shaman religion, had the most ancient, comprehensive, and detailed knowledge and method of astrology, geography, and mystical capacities. Mongolians knew the exact time of the year when the energy and influence of earth, water and star were high, and they used this energy and its influence in their life and governance. Shamanic knowledge helped them to find the correct deifying method and time and, in the process, to either protect themselves from powerful influence or properly use the weaker influences that were present. Contemporary shamanic knowledge is based on written and verbal information. Though some information is available about shaman’s memoirs, directions, and “callings” (including short rhymes or songs that are used to call the shaman spirit), it is still unclear how to correctly perform some shamanic rituals. Knowledge and rituals are mixed with Buddhist practices, information, and knowledge. For instance, though most people can name parts and accessories of shamanic costumes, people cannot explain their roles and symbolism of color, form and style. It is important to rediscover and reassert the historic and ancestral strengths of Mongolian shamanism for the benefit of Mongolians – and all of humanity.

Source

Author: Tuvshintugs Dorj

academia.edu