The Faithful Buddhist

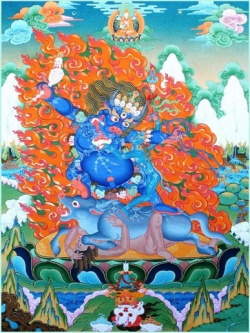

Apocalyptic Terror of the Collective Subject

In an essay entitled “The Spectre of Ideology,” written about twenty years ago, Zizek makes an observation about a change in capitalist ideology that is undoubtedly even more obviously true for us today. While in earlier stages of capitalism the assumption was that human beings inherently had a “productive-exploitive relationship with nature” and the debate was over which “form of the social organization of production and commerce” was best, today it is impossible to even imagine any other mode of production than capitalism:

Today, as Fredric Jameson has perspicaciously remarked, nobody seriously considers possible alternative to capitalism any longer, whereas popular imagination is persecuted by visions of the forthcoming ‘breakdown of nature’, of the stoppage of all life on earth—it seems easier to imagine the ‘end of the world’ than a far more modest change in the mode of production, as if liberal capitalism is the ‘real’ that will somehow survive even under conditions of a global ecological catastrophe… (“Spectre”, 1)

Any examination of popular culture today, and of what passes for left-wing politics, would suggest that this transformation has continued up to the present day. If it is a choice between changing our economic system and total annihilation, it seems we would choose annihilation—and that we cannot even imagine any change that does not involve destruction on a grand scale.

What does this have to do with Buddhism? Well, it would be my contention that reason for this abject failure of the ideological imagination is a complete incapacity to even contemplate the fundamental truths of Buddhism: anatman and conventional reality. Specifically, the inability to consider these concepts in their full implication leads to an inability to understand the collective nature of the human mind. Until we can begin to grapple with the possibility that the mind is a collective symbolic/imaginary system, until we abandon atomistic and empiricist models of the subject, we will not be able to conceive of a world not structured by capitalist social relations. And so, for those properly interpellated into capitalist ideology, any change to the social system will quite literally seem like the end of their “World.”

According to Zizek, for whom the Lacanian psychoanalytic understanding of the subject is not historically bound (that is, it is not an account of the modern, capitalist subject but of the way all subjects must always be), there is no real solution to the problem of ideology. Ideology will always function the way capitalist ideology does, and we will always need to be deluded and desiring subjects, regardless of the social system. His understanding is that “an individual subjected to ideology can never say to himself ‘I am in ideology’, he always requires another corpus of doxa to distinguish his own ‘true’ position from”(“Spectre”, 21); this situation, for Zizek, is “universal” because of the nature of thought itself: “we encounter the inherent limit of social reality, what has to be foreclosed if the consistent field of reality is to emerge, precisely in the guise of the problematic of ideology”(“Spectre”, 30). Zizek insists that this is an ontological truth, instead of a truth of capitalist ideology, which requires such foreclosures and exclusions precisely because it depends upon a delusion for its very existence.

This belief, I would argue, is a result of a subtle assumption that the subject must be both atomistic and at least in part unconstructed by the social system. In his critique of the neuro-cognitive attempts to account for the “illusion of consciousness,” Zizek mentions what he calls the “limitation of Buddhism”(Less Than Nothing, 720). Buddhist no-self theory, he tells us, “is not able to accomplish” the crucial “second step,” which he takes to be realizing that “the Subject is precisely Nothing!” Buddhism fails because it recognizes that there is no essential, eternal self directing consciousness, but then fails to see this gap at the center as the very nature of Subjectivity—the Subject is a lack or failure in the symbolic system of the big Other. The “Nothing” that is the subject is not, for Zizek, constructed; it is an unconstructed ontological truth. Unlike Nagarjuna’s concept of sunyata, which proposes that everything is dependently arisen, Zizek’s “nothing” is a lack in the symbolic order—not an argument about how the particular symbolic order is conventionally constructed, but a transcendent truth about all possible symbolic orders, and so all possible human subjects.

From a Madhyamaka perspective, however, Zizek gets it exactly backwards. To stop at the void is to make the mistake of assuming the existing social system, with its necessary foreclosure or exclusions and its atomistic individuals, is the ultimate truth. This is to forget to take the next step, which would require us to ask exactly why our symbolic system requires these particular exclusions, and what social practices are necessary to construct a subject that exist only in the place of the lack in the symbolic order? That is, the Faithful Buddhist would be the one who does take the next step, beyond realizing that “the self is empty,” to realizing that it is therefor conventionally real, and so can be conventionally reconstructed. The work begins at this point, with deciding what kinds of social practices would be preferable, and what different kinds of subjects we might be able to construct.

What if we consider the possibility that the symbolic only requires a constitutive foreclosure so long as we assume that the role of thought and language is the accurate depiction, reflection, or mapping of the world? In this case, we would need to begin with a goal of reification, of asserting final truth beyond question, and so the symbolic system would produce subjects located at the site of its lack, desiring and deluded subjects who can only survive by misrecognizing their ego as an eternal self. But this is to reject the basic insight we have been offered from thinkers in a number of traditions. Hume, for instance, offers the possibility that all causal explanation involving mind-independent reality must be reconceived as an attempt to do something, not as an accurate description of some “deep” causal mechanism. In Islamic thought, the twelfth-century philosopher Averroes, who was influential in bringing Aristotle to the attention of Western Europe, explained that following Aristotelian thought we must arrive at the conclusion that the mind is a collective process, not located in the body, but making use of individual bodies (see Fakhry, 70-73)—his thought horrified Aquinas, who set out to recover Aristotle for the Catholic notion of individual immortal souls.

Hegel, as well, becomes much less opaque when we understand that he is arguing for a kind of collective mind existing in social practices. For Hegel, moreover, it is not necessarily the case that we must always be deluded or in ignorance. It is entirely possible that we can achieve what Hegel calls “Absolute Knowing,” which is not, of course, omniscience in any positivist sense of having instant access to all “information” or facts; rather, Hegel suggest the possibility of an awareness of the conventional nature of our construal of the world. As Terry Pinkard explains it, the members of a community “come to see that they are indeed held together by a set of shared beliefs; that all actions are motivated out of a complex of passions, interests and so on, and that the significance of what one does is a matter of its recognition by members of the community”(219). What gives us agency is not some correct knowledge of external reality, but having a “place in a ‘social space,’ in [a] symbolic, cultural world”(222). In such a collective, there would not need to be a structuring lack, because there would be no need for reification, and no erroneous assumption that thought depicts the world. Instead, we would be participants in a communally chosen project, one which could (and even must) be subject to immanent critique and reconstruction. Pace Zizek, then, we could perfectly well be subjects who can say “I am participating in this ideology.”

The reason it is so much easier–and so much more fun, if we judge by popular culture–to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism is that we have so much difficulty conceiving of mind as a collective practice, existing in the social symbolic system and not in individual brains or souls. We tend to assume the capitalist subject, the individual trapped in a meaningless, alienated existence, is a universal, and not a conventional, reality. So much of our “high brow” art then asks us simply to embrace, even revel in, this alienation and despair—because to end them would require ending capitalism itself. For the good bourgeois subject, of course, the end of capitalism really would be the end of the “World” (in Badiou’s sense of the term). And that is an “end of the World” worth actively promoting.

Madhyamaka Buddhism is one among many discourses in history that have tried to force the Truth of anatman, including all its implications of the collective nature of the subject and the real causal power of the conventionally real. We cannot know in advance, or course, what kind of subject a community founded on Absolute Knowing would produce. Perhaps this not knowing is the source of the terror of real critical thought? In any case, it is clear that this fear is what makes real Buddhist practice so difficult. We must begin by taking the “second step,” beyond recognizing that the self is empty of essential nature, to analyzing the causes and effects of the practices that construct its conventional reality. Only then can we begin to collectively develop practices capable of producing different kinds of subjects.

Works Cited

Fakhry, Majid. Averroes: His Life, Works and Influence. Oxford: One World Publications, 2001.

Pinkard, Terry. Hegel’s Phenomenology: The Sociality of Reason. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Zizek, Slavoj. Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism. London: Verso, 2112.

—. “The Spectre of Ideology.” In Mapping Ideology, Ed. Slavoj Zizek. London: Verso, 2012.

1 Comment

by wtpepper on January 24, 2014 • Permalink

Posted in Uncategorized

Mindfulness or Mindlessness?

This is the title of a talk given by Robert H. Sharf, at the Advanced Study Institute at McGill University this past summer. I’ve posted a link to the talk below, and I highly recommend it for anyone interested in Buddhism in the West, but also for anyone who is at all affected by the new “mindfulness” craze in education and psychology. It is a half hour well spent, and raises some very important questions about the trend of using mindfulness to “cure” everything from ADD to PTSD, from depression to addiction.

I want to make just a few remarks about the talk, and I hope that it can spark some useful discussion here.

Sharf reiterates what other historians of Buddhism have been saying for some time now: that the understanding of “sati” as “bare attention” which requires “non-discursive, non-judgmental attending to the here and now” is a quite recent invention, dating from the 20th century. Furthermore, in Buddhist philosophical thought this idea of an awareness outside of all cultural and cognitive conditions is far from generally accepted. In many schools of Buddhist thought such bare awareness would be assumed to be impossible, and the idea seems to depend on a Western epistemology–particularly empiricism and the Cartesian/Lockean idea of a cognition-free “consciousness” that is the consciousness of the “soul.” (Sharf points out that Nyanaponika Thera, who popularized this understanding of sati, started out as a German student of phenomenology).

Furthermore, in attempting to make Buddhism into a “science” which will give us a “more emotionally fulfilling and rewarding life,” the mindfulness craze has eliminated an important aspect of Buddhism that goes all the way back to its earliest days: “Buddhism involved,” Sharf reminds us, “a critique of mainstream social and cultural values and held that liberation was not possible without a radical change in the way one lived.” Sharf also points to other instances of such popularist and at the same time politically quietist movements in Buddhism (in Chán and Dzogchen) and explains that they were also criticized in their time for rejecting fundamentally important aspects of Buddhist thought and practice.

There are two points on which I would want to extend Sharf’s discussion of mindfulness practice. One is when he simply sets aside the question of the efficacy of mindfulness in light of the body of “empirical evidence” supporting it. I would suggest that it can, in fact, have an effect on the practitioner—but that the effect it has is not at all the one it is assumed to have. In this regard, we need to question the “empirical data,” and not concede that it proves the efficacy of mindfulness. Certainly, as a social practice, convincing oneself that one has reached a state of “non-conceptual consciousness” can function as a kind of support for the ego, cathecting mental energy and helping to reify and naturalize one’s socially constructed construal of the world. In a word, so long as one is convinced of the dual ancient and scientific power of this practice, and participates in the social institution of mindfulness, it is possible that it can serve to more fully interpellate the individual into the dominant ideology, of which empiricism and belief in a transcendent soul are powerful components.

The second is Sharf’s claim that the underlying, but unnoticed, “metaphysical commitment” of the mindfulness proponents is the belief in perennialism. This does seem to be one such assumption, but I would suggest that perennialism itself is part of a more pervasive and subtle assumption: the belief in the atman. People often ask me why it is I always assert that mindfulness assumes the existence of, or reinforces the delusion of, an uncreated and eternal “self” or atman. Simply put, to be able to achieve “bare awareness” assumes that there is some kind of mind or consciousness that is uncreated by, not dependent upon, the phenomenal world, and which can therefore become aware of this world “as it really is,” separate from this radically dualistic mind that does not affect and is not affected by it. On this understanding, all of our cognitions are part of this phenomenal world, but our “pure consciousness” is not. (Sharf refers to this as the “filter theory,” in which language and cultural conditioning “filter” or obscure the eternal mind’s direct access to the reality separate from it.) Locke seems to have believed in such a pure consciousness (he suggests that the soul “thinks” outside of language, for instance), but it is antithetical to much of Buddhist thought, which assumes that consciousness and object arise dependent upon one another (as well as upon other conditions).

My suggestion here would be to listen to this talk, raise questions about it, and if you know anybody who is climbing on the mindfulness bandwagon, send them the link. As more and more people are being forced, in various institutional settings from schools and prisons to addiction rehabs and psychiatric hospitals, to submit to this practice, it is increasingly important to let them know that not only are they being asked to pretend do what is actually impossible, but that even the pretense is little more than a form of ideological indoctrination.

My last post argued that renunciation was, in the time of Early Buddhism, an openly political act. This talk reminds us that even the supposedly personal and individual pursuit of mindful bliss is also a political act, albeit a reactionary one which denies its own political nature.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c6Avs5iwACs&list=UUvwynGKKFos42dGxeU_TvnA&index=11

40 Comments

by wtpepper on January 4, 2014 • Permalink

Posted in Uncategorized

The Politics of Renunciation

My last post suggested that we need to change the social formations in which we live in order to achieve any liberation from suffering. Since we are constructed by the collective practices we take part in, we cannot hope to change ourselves without changing those practices. There were, as always, a number of x-buddhists who responded (mostly on other sites or by email) that Buddhism is about some kind of personal liberation, that “real Buddhism” has nothing to do with politics, that we can only seek personal contentment and should never try to change others or the world we live in. I’m fairly sure that most of these assumptions are carried into Buddhism by Westerners raised in a culture that insists on absolute separation of church and state; in fact, in our culture even political beliefs are thought to be “deeply personal” and not amenable to change by rational argument or empirical evidence, so clearly our “religious” or “spiritual” convictions must be even more deeply personal, individual, and beyond the influence of such trivial things as actual practices in the world. Things like our jobs and our culture’s moral beliefs and practices cannot have anything to do with our spiritual condition. With these very American assumptions firmly in place, converts turn to Buddhism for private, personal comfort, hoping to continue in their life as it is, but with less unhappiness. When even the Pope now says that we must change the capitalist economic system in order to be good Christians (http://www.salon.com/2013/11/26/pope_francis_capitalism_is_a_new_tyranny/), the hope is that Buddhism will offer a retreat from the demands for moral action, a comforting restorative meditative state to enable us go out and resume oppressing the rest of the world and destroying the environment with renewed vigor.

However, there are also those who point to specific Buddhist texts in support of the idea that liberation is a private and personal thing, not requiring any social activism. So in this post I want to respond to this question: does the concept of renunciation relieve us of the necessity of working to change our social system?

I will address this question in two parts. First, given that some of the earliest Buddhist sutras clearly do suggest renunciation and a somewhat individual pursuit of enlightenment, I will consider the political implications of such renunciations in the historical situation of early Buddhism. Then I will consider the degree to which renunciation is even possible for us today, and what it might mean for us, in our historical situation, to renounce the “householder life.”

Among the earliest Pali Sutras, the Sutta-Nipata is fairly explicit in advocating the life of the wandering mendicant as the only way to enlightenment. For some Western Buddhists today, this is taken to suggest that the practice of Buddhism, the pursuit of liberation from suffering, is something to be pursued outside the realm of social, economic, and political activity. In the first chapter of the Sutta-Nipata, “The Chapter of the Snake,” the second sutra, “Dhaniya,” ends with a clear statement that one can never gain enlightenment without abandoning the life of the householder, giving up concerns of family and the production of food:

‘One with sons grieves because of [his] sons’ said the Blessed One. ‘Similarly the cattle-owner grieves because of [his] cows. For acquisitions are grief for a man. Whoever is without acquisitions does not grieve.’ (Norman trans., p. 5)

Similarly, in the more familiar “Khaggavisana Sutta” (the “Rhinoceros Horn” sutra) we are advised to abandon the ordinary economic life when pursuing enlightenment:

Leaving behind son and wife, and father and mother, and wealth and grain, and relatives, and sensual pleasures to the full extent, one should wander solitary as a rhinoceros horn. (Norman trans., p. 9)

Having discarded the marks of a householder, like a coral tree whose leaves have fallen, having gone out from the house wearing the saffron robe, one should wander solitary as a rhinoceros horn. (Norman trans., p. 9)

Certainly most Western Buddhists are not interested in literally abandoning their houses and jobs and wandering in the wilderness, sitting in solitary meditation and begging for their one meal a day. However, such passages are taken to suggest that one becomes enlightened in solitary retreat from the world, not by engaging with it, and the assumption seems to be that while progress to full realization may be slower without such full renunciation, short periods at retreat centers or daily meditation practice will serve the same purpose, allowing us to forget the world and seek deep and profound truths in our spare time.

I would suggest, however, that this is to miss the profoundly political nature of the act of renunciation in the historical period in which Buddhism first appeared. Consider the political and economic world of India at the time. Technological advances such as the development of iron tools had made possible an enormous growth in productive capacity, and the advent of extended trade. Along with this, the long period of a static social formation managed by the brahmins began to be felt as an oppressive limitation. The sacrificial rituals, which clearly functioned in India in much the same way as they did in early Greece—as a mode of distributing social surplus and maintaining the social stability, began to be seen as a threat to productivity and as an oppressive restraint on human happiness. As Richard Seaford puts it in Money and the Early Greek Mind, in a social system that centers on ritual sacrifice, “the offering of food to [the priest] is an economically central practice, for it is identical with the gathering of food for storage and distribution at a centre. The motor of the system is divine demand”(74). The sacrificial ritual serves an economic function, and it then comes to be felt as an unnatural constraint. Burton Stein, in A History of India, explains that “many followers of both Buddhist and Jaina doctrines and monastic communities were people of wealth and property; the motive for supporting the anti-sacrificial faiths might have been the protection of their wealth from arbitrary appropriation and unproductive waste in sacrifices” (p. 73; on this issue, see also Hamilton, Chapter 3; Carritthers, Chapter 2; Gethin pp. 9-16). The invention of money is a social practice which make possible the transition out of this practice of distributing the social surplus. Buddhism arises during this process of social transformation.

If we understand the term “samsara” in its literal sense of “going around in circles,” then we can see the sense in which it refers to the stagnant reproduction of a social formation that is not open to change. As Richard Gombrich explains, the metaphor of nibbana or “putting out of fires” is a very politically charged one: “The brahmin householder had the duty to keep alight a set of three fires, which he tended daily. The Buddha thus took these fires to symbolize life in the world, life as a family man”(112). Achieving nirvana, extinguishing the household fires of the brahmin householder, is the way to achieve freedom from the endless reproduction of an increasingly oppressive social system.

But there is more to importance of “going forth” than this. One of the insights of Buddhist thought, the one most difficult for us to grasp still today, is that our social practices provide the very structure of our thought. Zizek (don’t stop reading, this point is fairly clear) explains the importance of this in his early book The Sublime Object of Ideology. Following Sohn-Rethel, Zizek argues that “the apparatus of categories presupposed, implied by the scientific procedure… the network of notions by means of which it seizes nature, is already present in the social effectivity, already at work in the act of commodity exchange”(17, emphasis added). The point is that even the most fundamental categories of our thought are structured by the social practices in which we participate; this is what makes thought possible, but is also what might limit our ability to think “outside” the economic system in which we live. The early Buddhist insistence on changing one’s actual mode of existence, one’s daily practices, in order to become able to “think” the conventional reality of the existing ideology, is a radical and brilliant insight, and an extremely politically charged concept as well. In addition, the early Buddhist warning against the use of money can be understood as a warning against escaping one source of delusion only to fall into another—the delusions produced by the ideological practice of exchange value. The renunciant is not seeking temporary relief from the pressures of daily life, to return to the same old social practice with renewed vigor. Rather, renunciation is an active social practice, enabling the practitioner to develop a “social effectivity” in which it becomes possible to think outside the World of the brahmin householder.

Let’s return, then, to the Sutta-Nipata, and consider what is actually being advocated. For one thing, even in “The Rhinoceros-horn” sutta, we are instructed to seek and find companions who share the same pursuit:

If one can obtain a zealous companion, an associate of good disposition, resolute, overcoming all [dangers], one should wander with him, with elated mind, mindful. (Norman trans., p. 7).

Isolation is not the primary point of renunciation; the goal in non-participation in the social practices one hopes to see through. Consider Saddhatissa’s translation of the passage from the “Dhanniya Sutta” cited above:

The Buddha: He who has children has grief on account of his children. He who has cattle has grief on account of cattle. For upadhi is the cause of the sorrows of men, but he who has not upadhi has no sorrow. (4).

The Pali text reads:

34. Socati puttehi puttimā (iti bhagavā)

Gomiko gohi tatheva socati,

Upadhīhi narassa socanā

Na hi so socati yo nirūpadhīt (Pali text society)

There are two key terms here. One is the term translated as both “grief” and “sorrow”: socati. The standard definition is grieving or mourning, but the root of the word refers to the burning of a fire; the metaphor recalls the burning fire as “attached” to its fuel, and so unable to stop its “grief” or suffering. The other term is upadhi, which Saddhatissa leaves untranslated. The usual tranlation is either “acquisitions” or “attachments,” but either of these misses the full sense of the term. The Rhys Davids-Stede Pali-English Dictionary suggest a more complicated meaning: “’stuff of life’, substratum of being…still dependent, not free, materially determined.” The householder is not suffering because of his acquisitions, but is limited in his thought processes because of his participation in the practices of the brahmin social formation.

What is essential to understand, then, is that in order to achieve liberation we must be cautious of the practices we participate in. Our capacity for thought, and so our capacity for liberating insight, is determined by the actual social practices in which we live our lives. Those who cannot grasp the core insight of dependent arising, of conventional reality, are not lacking in some “innate intelligence,” but are participating in social practices which make this insight literally unthinkable for them. Their categories of understanding are so structured that such insights appear to be either mystical or purely incomprehensible.

To conclude, then, I would ask that we consider what this means for us today? In our World we simply have to admit that being a renunciant is just not really possible. I don’t mean that it is difficult, or unpleasant, but that it literally cannot be done. When every inch of the Earth is somebody’s private property, there is no wilderness to wander into. It is literally legally impossible to grow one’s own food, gather wild food, beg for food, or live without any money. And, of course, to be put in jail is to be forced to participate in the existing social formation. Even the most radical of communes would be required to pay taxes, and so to participate in the monetary system and support the policies of the government.

So what can renunciation mean for us today? My suggestion would be that the only true renunciants today are the “bad subjects” of capitalism. Unable to walk away and create a social practice in which new forms of thought become possible, the only alternative I can see for our World, in which the global economy has penetrated into our every bodily sensation to an extent never possible before in human history, is to work against the existing social formation. The great insights of Buddhist thought were enabled by the period of transition from one social hegemony to another—it is not a matter of some great individual genius. Even The Buddha’s enlightenment was dependently arisen, occurring at a historical moment when the process of change made it possible to think outside the structure of the existing World. This thinking required the establishment of new practices, the social system of the sangha. If we are, to some extent, in the process of another such dramatic transformation, a shift to global capitalism in which the contradictions of the capitalist system are, momentarily, revealed, the question is what kind of practice can help us to see them more clearly, to use this crisis, and this transition, to enable true enlightenment?

Renunciation for us may have to be less peaceful rejection and more active opposition.

Works Cited

Carrithers, Michael. The Buddha. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Gethin, Ruper. The Foundations of Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Gombrich, Richard. What The Buddha Thought. London: Equinox Publishing, 2009.

Hamilton, Sue. Indian Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Norman, K.R., Translator. The Rhinoceros Horn and Other Early Buddhist Poems (Sutta-Nipata). Lancaster: Pali Text Society, 2007.

Saddhatissa, H., Translator. The Sutta-Nipata. London: Routledge Curzon, 1994.

Seaford, Richard. Money and the Early Greek Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Stein, Burton. A History of India. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1998.

Zizek, Slavoj. The Sublime Object of Ideology. London: Verso, 1989.

5 Comments

by wtpepper on December 23, 2013 • Permalink

Posted in Uncategorized

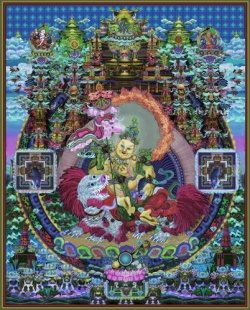

Conventional Reality and Social Construction

A few decades ago it became quite popular in many academic disciplines to announce that everything and anything is “socially constructed.” An enormous variety of things were suddenly “discovered” to have been social constructs, ranging from gender, emotions, and aesthetic taste to evolution, the laws of physics and reality itself. Some of these things clearly are socially constructed, others are clearly not—but what enabled this craze was often simple conceptual error. The most common error consisted of a failure to distinguish between the thing and our concepts about the thing. To take a simple example, evolution is a thing that really happens to life on our planet. It is not “socially” constructed, where “socially” is taken to mean constructed by human practice and discourse; however, our knowledge of evolution is socially constructed, in that it is made possible by human discourses and practices. More importantly, we produce this knowledge with some intention, to serve some purpose, and so our knowledge is always ideological. We could, for instance, refer to the same phenomenon as “adjustment to conditions” or “accidental adaptation,” which would suggest a very different ideological intention to the study of the same process. The real occurrence is the same, and is not “constructed” by human social practices, although our knowledge about the process is constructed and put to use in such social practices. This error should be simple enough to grasp, and has been pointed out many times for many years by more than a few analytical philosophers—although it seems to me that the error is even more common today, as when psychologists or Literary critics say that we cannot apply psychoanalytic concepts to explain any text or event that occurred before Freud began publishing.

There is a more difficult error in the social-construction approach that I want to address here, because I think it can help explain the common difficulty in understanding the Mahayana Buddhist concept of conventional reality, or samvrti-satya. This is the assumption that whatever is socially constructed has no real causal power, that what we construct socially is nothing more than error screening us from reality, leading to misunderstanding or deception. In Western Buddhism, this often takes the form of the belief in some “pure consciousness” outside of “views” or language; the idea is that what is samvrti-satya, or social, or conventional, is not real or truth at all, but is a distortion preventing our “thought-free” experience of some pure Kantian noumena. In Western thought, this mistake has led to a belief that once we understand something as “socially constructed” that is all we need to know about it—there is no need to know how it is constructed, or to understand the function and effect of the constructed phenomenon, because once it is “seen through” as a construct, it evaporates like a mirage. This error has led far too many people to turn to the psuedo-scientific pronouncements about neuroscience as the only “real” thing about the mind.

Because of this misunderstanding, the “social construction” craze has been all but abandoned. The rejection of “social construction” was not without some merit, of course. Too often, the term was used to allow for an absolute relativism, and to prevent serious scientific thought. But in rejecting the constructionist approach, we have also abandoned any hope of real thought about most of the things that are important to us, exactly those things which we can work to change.

To illustrate the difficulty in understanding this error, I will use the example of Ian Hacking’s thoughts on the matter in The Social Construction of What?, in which makes exactly this second error about social constructionism. I use Hacking as an example exactly because he is not some minor player making obvious errors, but has written extensively on the historicity of mental illness and scientific knowledge, including writing an introduction to the 50th anniversary edition of Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. That he continues to make this error is an indication of how difficult it is to overcome.

Accepting the distinction between our concepts of things and the things themselves, Hacking then makes the error of assuming that only the former can count as socially constructed, and so only the latter are “real.” For instance, he accepts that gender roles are constructed, because simply recognizing that they are conventions, not natural truths, has real power to “liberate” women from the guilt they feel over not having the socially expected feelings about motherhood (2). However, this doesn’t work with something like anorexia, because simply informing girls that their disorder is culture-specific “does not help the girls and young women who are suffering”(2). He cannot conceive of the possibility that something socially constructed can have real causal power, can be a really existing thing in the world, and that mere voluntarism, thought or “will” alone, cannot change it. In the case of anorexia, for instance, he argues that “social construction analysis” would be useless, because he cannot imagine that what is socially constructed could me more than a mere concept, but the very structure of the anorexic’s psyche, which will require a great deal of investigation and effort to reconstruct. The mind is not like writing on a chalkboard, wiped out and rewritten at will. It is socially constructed in the way that the streets of a city are—clearly they were laid out by people for a purpose, not a product of natural forces, but merely pointing this out does not even begin the work of trying to devise better patterns of traffic, much less of demolishing buildings and tearing up and rebuilding roads and bridges.

Hacking makes a similar point about child abuse, asserting that our idea of child abuse is socially constructed, but the thing itself is “real”(125). He can grasp that the psychological and sociological and legal concepts of child abuse are socially constructed, and amenable to change. What remains outside the realm of “construction” for him is the social structure that makes child abuse so prevalent and difficult to stop or even adequately respond to: the ideology of the autonomy of the nuclear family, as well as our political ideology that assumes individuals to be separate, autonomous, and private—the very division between public and private is an ideology, instantiated in concrete and non-illusory practices, that makes such abuse not only possible but more likely. To examine these social formations, however, seems somehow unscientific to contemporary thought, because what is socially constructed, it is assumed, is not “really real,” and cannot be scientifically studied.

These conceptual errors seem very difficult for most people to grasp. And the evidence from the history of Buddhist thought suggests that they have been difficult for other times and other cultures as well. There seems to be a tendency to make a division between what is real, and therefore unchangeable, and what is “mere” convention, and therefore unimportant. However, the concept of samvrti-satya was an attempt to correct this error. What is socially constructed is real, and has its own momentum and causal power, and we cannot pick or choose among conventional truths with some kind of transcendent “will,” because these truths are the structures which construct our minds.

Probably the most important passage in all of Buddhist philosophical thought on this matter occurs in Chapter XXIV of Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhyamakakarika, verses 8-10:

The Buddha’s teaching of the Dharma

Is based on two truths:

A truth of worldly convention

And an ultimate truth.

Those who do not understand

The distinction drawn between these two truths

Do not understand

The Buddha’s profound truth.

Without a foundation in the conventional truth,

The significance of the ultimate cannot be taught.

Without understanding the significance of the ultimate,

Liberation is not achieved.

(Garfield’s translation, 297-298)

All too often, the conclusions drawn from such passages are in complete opposition to the fundamental assumptions of Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka thought. Many Western Buddhist would read in this passage an assertion that the conventional is nothing more than “mere words” or “a finger pointing at the moon,” and take Nagarjuna to be suggesting some kind of mystical ultimate knowledge of “true” reality. Taken in the context of the work as a whole, however, we can see that Nagarjuna is suggesting the opposite. His point is not that we are trapped in the delusion of conventional truth, but that we fail to recognize that the ultimate truth is nothing but the awareness that our conventional truth is conventional—what we mistake for natural and real and uncreated is itself dependently arisen, conventional, constructed. To put this in the terms of the contemporary French philosopher Alain Badiou, a Truth must always appear in a World; we always live in a world, and any knowledge of mind-independent reality can only exist in a human social practice, as discourse producing that knowledge. In Althusserian terms, we always live in ideology, there is no ideology-free human activity. This doesn’t mean that we cannot produce knowledge of our conventional reality. That knowledge will be just as “conventional,” it will be constructed by humans, in human discourses and practices, with some intention. But it can still be correct knowledge. If we are motivated for ideological reasons to investigate the cause of a disease, we can still be right about that cause, and succeed in curing the disease; however, even our assumption that the virus is a “disease” is ideological, invested in our understanding of ourselves and motivated by our desire to reproduce our selves and our societies. It would be a great error to assume that because the vaccine for polio was “socially constructed” it is therefore mere illusion and not really effective (although there seem to be some people who do believe this).

Many Western Buddhists would say that the investigation of the social construction of our collective mind is not “real Buddhism,” because it is intellectual, and will lead not to passive states of bliss but to the sense of obligation to make endless efforts to change the world. My suggestion is that this is what Buddhism makes possible. The pointless “prapanca” so often warned against in Buddhist texts is not this kind of socially useful thought. Rather, prapanca refers to the kind of thought that tries to increase reification and avoid the recognition of social construction, creating often elaborate theories about things that don’t actually exist—the well known psychological theories about “intelligence” and “love” produced by Robert Sternberg come immediately to mind, but we could include most philosophical attempts to define beauty or the elaborate models devised by American economists in failed attempts to predict economic fluctuation. This kind of prapanca is indeed worse than a mere waste of time—it is the greatest bar to our attempts to successfully think about real social problems.

The key to understanding conventional reality is to avoid making the same mistake we have been making with the concept of “social construction” for the last three or four decades. The conventionally real is very real, has real power, and having its own “momentum,” is difficult to alter or eliminate. We must learn how things are constructed, what social practices create phenomena like mental illness, child abuse, poverty, ignorance and oppression. To understand the dependent origination of something like our attachment to the nuclear family, or even our idea of “childhood,” is not prapanca, but is to participate in ultimate knowledge. Ultimate knowledge is knowledge of the dependent origination of our conventional reality—not simply that it is socially constructed, but how it is constructed, what effects it has, and how it might be changed. This change cannot be a matter of mere recognition, of a “willed” changing of the mind, but must include effortful and sometimes uncomfortable changes in actual practices.

When we know how we are constructed in our social practices, we can know how to alter our social practices for the better. This is liberation: not the escape from the merely conventional, but the ability to engage with it.

Works Cited

Garfield, Jay L. The Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way: Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhyamakakarika. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Hacking, Ian. The Social Construction of What? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.e HeHe

28 Comments

by wtpepper on December 1, 2013 • Permalink

Posted in Uncategorized

A Buddhist Reads The Hunger Games

A note to any readers new to this blog:

This post is assumes familiarity with concepts that have been discussed on previous posts, and may seem confusing without that context. It might be helpful to at least read the post “The Truth of Anatman” before reading this discussion of The Hunger Games.

If you haven’t heard of The Hunger Games, you probably don’t have teenagers in your life, or just don’t watch popular movies or read magazine covers at the grocery checkout. The enormously popular trilogy of dystopian novels is widely read even by adults, and has become assigned reading in many middle schools, high school, and is even frequently taught in college classes. The movie of the first book of the trilogy is the all-time 14th-highest-grossing movie in America, and was the best-selling DVD of 2012; the movie of the second book in the series is due to be released this month. Considering the publicity this movie release is bound to generate, and the fact that the trilogy is so often required reading for young students today, I thought it was worth considering exactly what ideology these books are producing.

I’m going to try to avoid the simplistic assessment of moral content, and discuss ideology in the sense I have defined the term before; specifically, what kinds of subjects do the readers of these books become by reading and enjoying them? What is the function of the practice of reading The Hunger Games in the reproduction of the existing social formation? It is my argument that this novel serves to produce and reproduce a subject of late capitalism willing to consent to live in ignorance and delusion, happy to give up its right to live as a human subject in return for the mere fantasy of imaginary plenitude. In the terms of the echoes of Roman Empire that run throughout the series: The Hunger Games trilogy serves to produce good slaves for the global empire of Capital.

In a very enjoyable and entertaining way, we are reinforcing our children’s inability to escape the illusory surfaces of postmodern culture, insuring they will never achieve true agency, and will live lives of quiet misery addictively consuming pleasurable objects that always leave them more enslaved. But hey, at least they’re reading, right? That must be good!

And certainly the educators who are assigning the book are under the impression that it is producing the best kind of ideology. Recent essays on the novels assure us that they subvert oppressive gender ideologies, critique the culture of reality television, encourage contemplation of complex moral issues, and motivate young readers to become engaged in politics (Pharr & Clark, eds). But as I said, I want to look below the superficial. Because certainly none of the teenagers reading this book have abandoned their stereotypical gender roles, become involved in politics, or turned off Keeping Up With the Kardashians. The novel doesn’t function at this superficial or didactic level.[1]

Instead, we need to consider how the novel, in its content and its form, functions to reproduce the psychic structure of the late-capitalist subject. To do that, we need to subject the novel to a Lacanian critique, to examine what kind of reader we become by enjoying this novel.

But first: what kind of subject does late capitalism need? Let’s consider, briefly, the important work of Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello in the book The New Spirit of Capitalism. Boltanski and Chiapello attempt to account for the capacity of capitalism to produce new ideological forms as the dominant form of accumulation and appropriation changes. For my purposes here, I will only sketch part of their argument, but the book is well worth reading. Their claim is that the energy, the motivating power, for the ideological transformation comes from the critique of the previous stage of capitalism. The new spirit, then, is generated from the critique of the older forms of capitalism, which helps to produce a new ideology that can inform and enable the new methods of capitalist accumulation. This is clearly the reason The Hunger Games appears to be somehow radical, subverting the status quo. It employs What Boltanski and Chiapello explain are the four “sources of indignation” toward capitalism: “capitalism is a source of disenchantment and inauthenticity”; “capitalism is a source of oppression”; “capitalism is a source of poverty among workers and inequality on an unprecedented scale”; “capitalism is a source of opportunism and egoism, which, by exclusively encouraging private interests proves destructive of social bonds and collective solidarity” (17). The aim of critique, however, is not to remove capitalism, but to modify its ideological forms, its reproductive practices, in ways that are claimed to be less oppressive, more authentic, more fair, and less corruptible and combative. The Hunger Games, then, uses the classic charges leveled against capitalism, leveling them against “the capitol,” but its goal is to produce a postmodern ideology in the sense that Fredric Jameson used the term decades ago: as a cultural logic (or, ideology) of late capitalism, an ideology which eliminates any possibility of true agency in producing the subject drained of any capacity for sustained critical thought. The subject best suited to the latest stage of capitalism is one which is willing to accept conditions that would have been unthinkable to our grandparents. The new worker must be endlessly available, must be willing to see unemployment or uncertain employment as a kind of freedom, and must become someone who puts “a premium on activity, without any clear distinction between personal or even leisure activity and professional activity. To be doing something, to move, to change—this is what enjoys prestige”(New Spirit of Capitalism, 155). This subject seeks infinite and useful connections, over deep and meaningful relationships; her every action is a performance, designed to demonstrate her innate abilities, not simply an ability to adapt to any situation but the possession of some innate talent that specially enables her to transform the situation. She must first seek to attract attention and be noticed, because the alternative is to “risk passing unnoticed or, worse, being adjudged wanting in status and assimilated to the little people” (New Spirit of Capitalism, 461). It is essential that the subject’s abilities be unique, talents that are inborn and not skills that can be learned through hard work and proper training, to assure the subject of late capitalism a chance to stand out and succeed in the game. It is also crucial that this new subject be one who is seen as authentic, not performing or thinking or planning but simply reacting, with a gut-level instinct, in always the right way. The new subject of capitalism is not one who shows up to punch the clock and works hard until the whistle blows, but one who stands out, attracts attention, and has that special “something,” the “it,” that catapults her instantly to the top. In this way, lack of success is not a failure of the system, or even of individual hard work, but just a judgment from the “Other” that you don’t “have it,” and are somehow worth less than those who do.

It will be my argument that the novel The Hunger Games (I will focus on the first book, although I will mention the other parts of the trilogy) functions to teach our children to internalize this ideology of the subject, making them into passive reactants instead of active agents, convincing them that they should never work for anything, that their abilities are innate and cannot be developed, that they should avoid at all costs serious thought about the system to which they must only react intuitively—and that if they don’t succeed, it is because the Big Other has judged them irreversibly inferior in their very souls.

The novel The Hunger Games attempts to make us into this kind of subject by taking us through the process of Katniss’s resolution of her Oedipal Complex. In his essay “The ‘Uncanny’,” Freud explains the source of our combined fear and pleasure in reading E.T.A. Hoffman’s short story “The Sandman.” The story recalls, but in an indirect almost allegorical way, our own experience of resolving the Oedipal complex; as a result, we enjoy the particular kind of “fear” peculiar to the horror story because it reminds us of something that was once present to our mind but has become repressed or, to use Freud’s term, “surmounted.” The crisis is recalled, but re-contained, and the pleasure comes from the dual sources of both confirming the successful “surmounting” of this danger and indulging in the temporary fantasy of achieving the forbidden pleasure we have renounced. The horror story, then, functions to reinforce our proper interpellation into the symbolic order. The Hunger Games, I would argue, functions in a similar way, retracing the path through the Oedipal stage in order to re-interpellate the reader, making her or him into a more properly postmodern subject, with a particular relation to the symbolic and imaginary registers that makes the practices and beliefs of this subject of late capitalism possible—that, in fact, makes them seem almost inevitable.

In Lacanian terms, the resolution of the Oedipal complex depends upon entry into a Symbolic system. The individual must move out of a more thorough immersion in the Imaginary and into the Symbolic system of the Other, into language. The Imaginary, in the Lacanian sense, is the realm of bodily experience of and interaction with the world, the organization of our perceptions. As the individual enters the Symbolic, there is a sense of loss, a sense that the language requires a level of abstraction causing us to lose some of our direct experience of the world. This loss can generate the fantasy of “Imaginary plenitude,” the desire to return to this (never actually existing) state in which we had a direct, unconstructed, pure and “full” perception of the world, as well as the instant and effortless gratification of every wish through thought alone. The entrance into a Symbolic order does require the acceptance of some loss, the loss of the possibilities of the nearly infinite other Symbolic structures we could have entered; in addition there is the necessary exclusion, the reality that no Symbolic system can ever fully include every possible experience of the world—a Symbolic system is always incomplete. Accepting this loss, and entering the Symbolic system, requires containing the fantasy of Imaginary plenitude (often perceived as a female or maternal excess of threatening incoherent presence), usually with the help of the moral restrictions or code of the superego (often in the form of the forbidding law of the father). When this works properly, we are interpellated into the ideology of our social system, and we become good subjects, working as we should, perpetuating the system that has created us.

We have become subjects, then, in the psychoanalytic sense, but not in the sense that Badiou means by the Faithful Subject. The Faithful Subject, the subject of truth, will always refuse to be so perfectly interpellated, refuse to accept the existing structure of the Imaginary and Symbolic, and will work to force the appearance of a Truth into the Symbolic system—never completing it, never arriving at the final dogmatic answer, but always expanding the capacity to interact fully with the world. It is only this “bad subject,” this Subect of Truth, who is fully human, for Badiou. I would add that this is the awakened subject of Buddhism, conscious of the constructed, conventional reality of its Imaginary and Symbolic registers, and so able to increase our human capacity to interact with the world. And it is the possibility of such an awakened subject, a subject with true agency, able to consciously change our social formation instead of adapting to it, that cultural objects like The Hunger Games function to prevent.

At the level of content, it is clear enough that the novel is about Katniss working through her Oedipal complex, arriving at the compromise that makes her into the perfect postmodern subject. Her mother is effectively absent, failing to provide the physical maternal care, sunk in depression; the absence of the mother, the realization that her desire for the father precedes her love of the infant, is what typically is understood to initiate the oedipal crisis, and here Katniss is literally faced with the truth that her mother’s love for her husband and grief over his loss exceeds her love for her children. Her father’s death in a mining accident effectively kills off the entire world of actual work for Katniss. Somehow, she must construct a subject without the maternal Imaginary register of home and comfort and childhood and without the paternal Symbolic register of work and language and law. Unable to pass through the Lacanian mirror stage in the traditional way (very early in the novel, she says that she “can hardly recognize [herself] in the cracked mirror”[Hunger Games, 15]), she must find an alternative method of constructing a self.

We can easily trace the various substitutions for the maternal and paternal figures in the novels. The role of the father, the subject in whose eyes we seek approval and whose gaze we internalize as the superego, is split onto many figures, all of whom Katniss imagines or knows watch her and pass judgment, meting out punishment or reward: Gale, Haymitch, Cinna, Snow. The Maternal function of bodily care is transferred to Prim, to Rue, later to Coin, the oppressive overbearing mother who “cares” for the rebel forces of district thirteen. Katniss performs for the father, usually anxious about what each of the male gazes will see; she is comforted by the maternal presence she repeatedly tries to save, but finally must kill (when she shoots Coin in the third novel) to reach the full resolution of her Oedipal crisis.

We could extend the psychoanalytic reading to each element of the novel. Her unembarrassed nakedness in front of Cinna, who makes her beautiful for the crowd, and to whom she speaks when she realizes that she is “no one at all”(Hunger Games,118) except when she addresses herself to his gaze (during her interview, she is made appealing to the crowd by addressing her answers to Cinna’s gaze). President Snow is the terrifying punishing father, threatening castration (in the Lacanian sense of the loss of power to act in the world), described as a vampire whose breath smells of blood, and as the singular male source of all law and punishment. There is the phallic symbol of her bow, the games themselves as a symbolic sexual initiation, which kills off her last hope of return to the infantile state when Rue dies. As the series progresses we see Coin, the dictatorial mother figure of the rebellion, the symbolic wife of Coin, who represents the obscene combination of oppressive maternal care with extreme self-discipline and denial, of maternal comfort as asceticism (not unlike the Western image of Buddhist meditation); Coin also figures as the horrifying Western image of communism, presenting the only alternative to Katniss’s full interpellation as a subject of “Capitol” in the form of the western ideologeme of communism as joyless totalitarianism, discipline, and deprivation. Caught between the confusing multiplicity of male gazes and the maternal that alternates between complete indifference and suffocating presence, Katniss struggles to find an Other in whose unified gaze she can construct a functioning self.

In the process, of course, the novel demonstrates the new relation to work and to other individuals so necessary to late capitalism. Thinking about the social formation and how to transform it is always a terrible thing; those who do it are either portrayed as the ranting, angry Gale (in the end, Katniss must reject Gale because his “fire” is “kindled with rage and hatred” [Mockingjay, 388]), or become hopelessly alcoholic, like Haymitch. Even the scientists, creating new technology and making the rebellion possible, are portrayed, as Boggs is, as pathetic, stereotypical nerds bordering on mental illness. The ideal subject must only react, by instinct, to any situation, the way Katniss reacts in every stage, from her first impulse to volunteer in place of Prim to her shooting the arrow at the gamemakers in her private session to the later parts of the series proceeds where we are repeatedly shown Katniss being most appealing when she acts by instinct, without plan (as in the attempts to create TV spots for the rebellion, in which she is unable to “act” so they must use “candid” footage of her). It is imperative that the new subject of capitalism derive her wealth and position from an inherent, unteachable, unlearnable skill—it must be a unique quality of the individual that is deserving of wealth and success, never pure effort, intelligence, or hard work. Katniss’s abilities are natural, inherited from her father (they can’t, for instance, be taught to Prim, who is “by nature” a healer, like her mother). The tributes from the first two districts, who train specifically for the games instead of cultivating their natural talents, are the supreme villains of the first book of the trilogy. Work, of any kind, is never visible in this novel; the subject of the post-industrial “first world” knows that manual labour is done elsewhere, by those not quite fully human, not real subjects with unique talents and personal worth (even the production of food, for Katniss, must be a form or recreation, hunting and gathering as sport instead of planting and cultivating as labor). The goal is never to outwork others, to be better or smarter or more disciplined, as in the old “spirit of capitalism”; the goal now is to get attention, to be noticed, to stand out for something that is beyond definition or understanding and so can’t be artificially produced. It is also important to consider every relationship only in in terms of its productive or harmful potential. This is what Katniss does, throughout the series, becoming the center of all attention in and out of the “arena.”

What is it, then, that enable Katniss to resolve her particular Oedipal crisis? In this world in which the traditional paternal and maternal functions of the Oedipal complex no longer operate, how does one become a subject willing and able to suffer the complete loss of real power to act, think, or create, even to interact authentically with any other human being?

The solution lies in the strange new form of the Other. The Other, that core Symbolic structure which produces the subject, a kind of Subject with a capital S in whose gaze we seek approval, becomes now the postmodern Other of audience, of public opinion. The Other is that conflicted and inscrutable gaze for whom we must perform without instruction, never knowing in advance what is demanded of us. Think of the reality shows like American Idol, where the viewers vote decides who becomes rich and famous and who is forgotten and returned to poverty and obscurity. For Katniss, who cannot know what the Other is thinking, because the other seems to be thinking so many contradictory things, the only solution is to react, and if her emotions and intuitions are correct, she will be rewarded. She is caught between trying to please the various father figures in the novel (kissing Peeta will please Haymitch but hurt Gale); so, ultimately, she must play to a more abstract “audience.” And this audience is the most impossible of all. On the one hand, there is no individual who enjoys the game—the audience is forced to watch their own children die, as punishment, and so wants to see the “game” subverted. On the other hand, the audience desires suffering and violence—when things get too slow in the games the forest is set on fire, burning Katniss severely, to keep “ratings” up (although there seems to be no alternative but to watch this event). The audience hates the games and the capitol, but at the same time is the Other who demands the games it hates be made even more hateful to itself. The presumed viewer of the games is not someone who exists anywhere in the world of the novel—just as the viewer of the television shows we watch is always someone else, someone less intelligent or refined than ourselves, who excuses the elements of the show we cannot admit we enjoy. It is in finding an “authentic” and unplanned response to this conflicted, anonymous, incoherent and inscrutable other that Katniss becomes the thoroughly postmodern subject. The subject incapable of work, planning, thought, emotional stability, trusting personal relationships, but who nonetheless “plays the game” it claims to hate, knowing that whether it is chosen or is “passed unnoticed” and becomes “one of the little people” is beyond anything its effort could control The promise of the fantasy of imaginary plenitude, infinite wealth, comfort, and idle time to engage in creative hobbies (or just drunken excess) is all the compensation the postmodern subject gets for forfeiting its chance to live as a human being with real agency.

In the end, Katniss is properly interpellated, living a nice domestic married life, raising the two children she had once sworn she would never have, and working on her book of memories with her addled but loving husband by her side. But where does this leave the reader? How does the novel work to create this desire for imaginary plenitude in us? How does reading such novels make imaginary plentitude into the structuring fantasy of our ideology, making us into subjects terrified of effort, thought, or agency?

This occurs in a number of overlapping ways. First, most obviously, the experience of fiction as that activity in which we can imagine our psychosexual dramas being played out with none of the constraints of real life—fiction becomes a kind of daydream fantasy in which real life concerns like actually producing food and clothing and shelter, not to mention laundry and cleaning and cooking, are replaced by concerns of eating and wearing and thoroughly non-productive thrilling activity. Then there is the dimension of the book’s very popularity and the movies made of it, enabling us to participate in a virtual collective community of Hunger Games fans in place of interacting with real people, the movies allowing us the fantasy of having the desire the book produces fulfilled in a fuller yet more passive fashion as viewers (a fantasy that almost always becomes a let down when the movie “isn’t as good as we hoped,” but the next one…). The obsession, too, with the enormous amounts of money made on this novel, and the author herself becoming Katniss, telling a tale she deeply felt and being granted all the attention, adoration, and wealth of a winner of the Hunger Games.

The most concrete production of this subject, perhaps, is done by the function of the narrative voice. Katniss inhabits the impossible fantasy position of the ideal subject the reader wishes to be. Impossible because she is a teenage girl with very little, and very poor, education, who yet speaks fluent and proper English, is amazingly articulate, and skillfully tells her tale in the most artful way, to an audience who, in the world of the novel, cannot exist. We hear her thought, as it were, in the present tense, as if this is what she is feeling and thinking at this moment, and she has no idea what will happen next. She is devoid of guile, never pauses to contemplate, only remembering past experiences as evidence that she has felt deeply enough and suffered sufficiently to deserve our admiration. She has never thought at all, has made no plans for success, has only ever acted, instinctively, to survive—and that is how we know she is “authentically” the self we should identify with. The narrative voice is an impossible subject position, but the only one capable of meeting the demands of the impossible Other of an invisible popular opinion. As readers, we must become this impossible, inscrutable Other, disapproving of the very actions we are taking intense pleasure in witnessing; to the extent that we enjoy reading these novels, then, we both become and make possible the postmodern subject, a subject impossibly “knowing” but never thinking, capable only of feeling and reacting, but never of planning and producing.

In the end of the series, Katniss is left to suffer through the lifelong agony of accepting her fame, universal adoration, and limitless wealth and influence. The very intensity of her misery is proof that she deserves to be the focus of the Other’s gaze. The reader is left with no solution to the postmodern situation, then, but to avoid thought and work, mindlessly accept the social system as beyond change or even comprehension, and adjust to it by trying to feel deeply enough to attract the gaze of the Other.

As Buddhists, then, how do we react to this kind of ideology? Is there any way to respond? Consider the level of serious thought and intellectual engagement necessary to even grasp the ideological function of this novel? Is sitting in mindful contemplation of the present moment any kind of response to the suffering this will cause for the next generation?

In the World (in Badiou’s sense of this term) of American culture, all capacity for critical thought has been virtually eliminated. All of the tools which made ideological critique possible thirty of forty years ago have been systematically eliminated from our institutions of higher learning, dismissed as irrelevant, usually with no more argument than a huff and a roll of the eyes; psychoanalytic theory, literary theory, cultural criticism, marxism, radical feminism, are no longer visible in the academic journals of any discipline, and the return to positivism, accompanied now by uncritical relativism, rules the day. In the mad rush to embrace The Hunger Games as a tool to “get students reading again,” there is not a single voice of concern about the ideology being produced, because ideological critique is just no longer done.

If Buddhism has anything to offer the world today, it may be that it is the one place where the capacity for critical thought can be kept alive. The goal of the educational institution has always been to reproduce the existing relations of production, not to critique them. The goal of the Faithful Buddhist, on the other hand, is to use rigorous thought to bring to conscious awareness the causes and effects of our conventional reality. What ideology of the subject are we producing, and is it the best one? The goal of cultural objects like this is to convince the audience that such thought, such enlightenment, is unpleasant, undesirable, or even impossible, so that they will continue as unthinking machines reproducing the capitalist social system.

The mind is a collective process, produced in our collective Symbolic and Imaginary systems. As a Faithful Buddhist, it is not acceptable to let others live out their lives in this ideology of deluded ignorance, hoping that someday their suffering will bring them wealth and fame, and when it doesn’t remaining convinced that the failure is some deep flaw or defect in their “true self.” We need to try to explain the dangers of this horrible ideology, to awaken the fans of these sick fantasies. We can’t stop people from reading the books and watching the movies, nor should we try—but we can refuse to allow them to be required to read and watch.

I’m going to summarize here, in one paragraph, my position on what reading this novel as it is meant to be read, without serious ideological critique, functions to do:

In reading The Hunger Games and identifying with the impossible position of the narrative voice, engaging in the fantasy dystopian world from which all production and real social relations are excluded, immersed in Katniss’s primary narcissism in which every other can only be considered in terms of relations to the self—every other person becomes only a “self object,” the reader is interpellated into the ideology of late capitalism and becomes a subject for whom the late-capitalist social formation is not only tolerable, but simultaneously unthinkable and desirable. This subject, lacking a unified Other, is unable to construct a unified ego (self, or conventional self), and must endlessly seek the approval of the Obscure Other of public opinion, motivated only by the desire for the impossible fantasy state of imaginary plenitude. All collective or organized effort becomes obscene or evil, and the subject must act only on “instinct,” or “intuition” or “gut feelings”; thought and planning and preparation become the horrifying “over-intellectualizing” or “inauthenticity” demonized by contemporary psychotherapy and popular culture. This new subject experiences powerlessness and ignorance as “authenticity” and “freedom,” and is left to only feel deeply, hoping to some day attract the gaze of the Obscure Other and gain imaginary plenitude. Any suggestion of social change, then, becomes terrifying, because it might rule out their chance to win this bizarre social lottery and gain the prize their “true self” deserves to win. This subject, only able to do what “feels” natural and authentic, is of course unable to “pay attention” or perform sustained thought, and we create a generation of mindless drones for late capitalism. This is, of course, the role of the schools as a ideological state apparatus; no wonder then that teachers everywhere have embraced The Hunger Games.

Finally, my position would be that to read this book, and watch this movie, with a fully critical approach, analyzing the ideology being produced, is even preferable to ignoring the book. These books are so popular exactly because they reproduce and strengthen ideologies already in place in our social practices. Critiquing a book like this can help us to see how the postmodern subject of late capitalism is constructed, and to become conscious of our ideologies. The novels themselves can never do this, can in fact only do the opposite. But critique is a social practice just like reading novels and watching movies, and it can produce an ideology, and a subject, of a different kind.

Works Cited

Boltanski, Luc & Chiapello, Eve. The New Spirit of Capitalism, Trans. Gregory Eliot. New York: Verso, 2005.

Collins, Suzanne. The Hunger Games. New York: Scholastic, 2008.

—. Mockingjay. New York: Scholastic, 2010.

Freud, Sigmund. “The Uncanny,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. & trs. James Strachey, vol. XVII. London: Hogarth, 1953, pp. 219-252.

Pharr, Mary F. & Clark, Leisa A., Eds. Of Bread, Blood and The Hunger Games: Critical Essays on the Suzanne Collins Trilogy. London: McFarland & Company, 2012.

Note: I made some revisions to this post on 11/17, correcting some typographical errors and adding a couple of paragraphs. I know, it’s too long already–but I would need three or four times this length to really fully address all the terrifying implications of the ideology of the Hunger Games franchise.

[1] In her essay in The New Yorker (June 14, 2010) Laura Miller makes the point that these novels aren’t really “about” politics or violence or reality TV or moral issues, but are about “the stormy psyche of the adolescent reader.” However, in my opinion she reads the novel too allegorically, and doesn’t consider the possibility that narrative fiction can also construct the psyche it is (symbolically) “about.” She sees the novel, then, as functioning like the dream in Freudian theory–as wish fullfillment (Katniss is “forced to live every teenage girl’s dream.”) While the novel does, to an extent, function like a dream, it is not only a royal road to the adolescent unconscious; the practice of reading also functions to produce the structure of the psyche, and so of the unconscious.