I’M NOT TELLING you where it is. But in order to reach Shambhala, you need a mixture of merit and dumb luck, and at first the dumb part seemed to be working. When I wrestled my luggage, packed with clothes for three climates and obscure tracts from four religions, onto the night train out of New Delhi, there was something auspicious in my bunk assignment.

Shambhala

Tibetan workmen in the frontier town of Doma, near the Chinese military–controlled Aksai Chin

Tibetan workmen in the frontier town of Doma, near the Chinese military–controlled Aksai ChinShambhala

Approaching the Lake of Compassion, on the holy mountain of Kailas

Approaching the Lake of Compassion, on the holy mountain of KailasShambhala

Nomads ascend the 18,030-foot pass of Dolma La, on Kailas

Nomads ascend the 18,030-foot pass of Dolma La, on KailasShambhala

Herding sheep, west of Kailas

Herding sheep, west of KailasShambhala

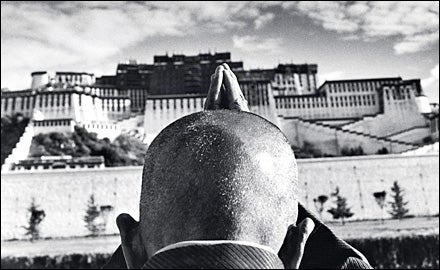

Accumulating merit at the pilgrims' temple of Jokhang, in Lhasa

Accumulating merit at the pilgrims' temple of Jokhang, in LhasaShambhala

The bazaar in bustling Hotan, in Xinjiang

The bazaar in bustling Hotan, in XinjiangShambhala

Budhist monks from the ancient Nyingma sect, at work in the fields near Kailas

Budhist monks from the ancient Nyingma sect, at work in the fields near KailasShambhala

Workers leaving the Silk Road ruins that may have inspired Tibetan tales of Shambhala

Workers leaving the Silk Road ruins that may have inspired Tibetan tales of ShambhalaShambhala

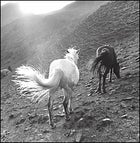

Grazing in the Tian Shan

Grazing in the Tian ShanIt was a sleeping carriage, the start of a run east. Tomorrow I would cross the border to Nepal on foot. Then on to Kathmandu. Then Lhasa. Then over Tibet and onward, sometimes west and always north, to places unknown. Tonight the train was jostling, hot, full of brilliant Indian colors and smells, the famous synesthesia of the subcontinent, too much of everything. The cabin had four bunks. The pair on the right were occupied by a Brahmin couple, having their feet kissed in farewell by their adult children. And on the bunk below mine, what had to be perfect luck: a Buddhist monk, his elegant robes dark mustard, his disposition affable.

One is enjoined to seek, on the road to the hidden kingdom, the blessing and advice of wise monks, and around midnight, after rubbing menthol all over himself, this learned man listened to my plan. I was setting out on the ancient pilgrimage route to Shambhala, I told him, to seek the king and paradise here on earth. I was afraid, I said. Did he have any advice?

@#95;box photo=image_2 alt=image_2_alt@#95;box

No. Any teaching? No. Any blessing?

No. Shambhala was “lama nonsense,” he said. A Thai, he didn’t believe in the stories, carefully curated over the centuries by Tibetan Buddhists, that Shambhala was a real place, a city that could be found. Shambhala, the monk told me, was a destination for an inner journey. I should meditate more, he suggested, and travel less.

“Don’t go,” he said, and went to sleep.

Most people had that reaction. The Buddhism scholar Robert Thurman looked at me with pity when I mentioned my quest during a chat at Tibet House, in New York. Gene Smith, who directs the city’s Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center, laughed out loud when I told him my plan. “We got a guy here going to Shambhala!” he shouted.

At a conference a couple of years ago, I ran into Peter Matthiessen, the author of The Snow Leopard, which mentions Shambhala three times, speculating that the hidden kingdom may have been based on some real but forgotten city or culture, out beyond the Gobi. “One must go oneself,” he wrote, “to know the truth.”

So I told him I was going. Matthiessen shook his head. “It’s really more of an idea,” he said.

By consensus, I was on a fool’s errand, headed to a place that couldn’t be reached.

SHAMBHALA IS THE OLDEST and purest vision of enlightenment, a prophecy that became a place and, finally, a legend. Varieties of the myth are shared among Indian Hindus, Chinese Taoists, and Tibetans of both Buddhist and Bon persuasions. It is the Ultima Thule of the East, a promise that a golden age will be restored by the king of a great northern paradise, riding forth on a white horse to destroy the barbarians of the world, to stamp out materialism and immorality and bring an end to this dark cycle of time. It is, in other words, what human beings need to believe in. A promise of eternity, and the return of hope.

From one of its earliest mentions, written perhaps before 300 B.C. in the Mahabharata, the first Hindu epic, the legend of Shambhala took more than a thousand years to reach neighboring Tibet. There it found its greatest guardians as the Tibetan Buddhists transplanted the myth into Nepal, Sikkim, Mongolia, Ladakh, and as far afield as Beijing. The Tibetans claimed that the Kalachakra, the secretive mixture of tantric scriptures and meditation doctrines that form the highest teachings of Tibetan Buddhism, was sent to them by the King of Shambhala, using the ninth-century equivalent of express mail. They filled their holy books with descriptions and dashed off instructions for reaching the lost land.

Shambhala is a moving target. The Hindus thought it was up toward Nepal, the Nepalis in Tibet, the Tibetans in the northern deserts, always somewhere farther than the known. Yet seeking to actually find Shambhala here, on this earth, is really not unreasonable. Unlike the Christian heaven, Shambhala is an earthly paradise, solidly grounded on the surface of this planet. The current Dalai Lama insists the kingdom is real: “If so many Kalachakra teachings are supposed to have come from Shambhala,” he has said, “how could the country be just a fantasy?” Contemporary Tibetan monks have posited that Shambhala can be found in Siberia, or at the North Pole.

I had a little help—from scholar Edwin Bernbaum, director of the Sacred Mountains program at the international nonprofit Mountain Institute and author of the definitive book on the subject, The Way to Shambhala. When I called Bernbaum at home in Berkeley, California, to ask where Shambhala could be, he first played hard to get (“Right here,” he said, laughing; “if you could really be present, Shambhala would be right here.”) and then put his figurative thumb on a map of western China.

Whatever lost city or ancient kingdom had inspired the Tibetans to pin the wandering myth of Shambhala onto one particular plot of earth, it was probably there, he said. The Tibetans’ Kalachakra teachings had come from Central Asia in the late first millennium, almost certainly composed in monasteries along the Silk Road. Decoding the scriptures and cross-checking them with archaeological evidence, Bernbaum had found a “likely historical prototype,” one “interesting kingdom” that had thrived as a center of Buddhist scholarship, only to disappear under a wave of history just as the Tibetans were grappling with its teachings. City and paradise were conflated.

Bernbaum had been there himself, he said, in the 1980s, although travel restrictions had kept him from making the original pilgrimage north, from Tibet itself. I was in a better position. With borders open, I could attempt the ancient route spelled out in Tibetan texts.

Several guides to Shambhala were written over the centuries. There was a thousand-year-old passage in the Tengyur, part of the Tibetan canon of holy books; an account by a 13th-century lama named Manlungpa ending in the almost casual mention that he’d been there himself; and a florid 1770s description by Palden Yeshe, the third of the Panchen Lamas, said to be pre-incarnations of Shambhala’s future king. But the most affecting was a desperate plea for help, a letter called “The Knowledge-Bearing Messenger,” written around 1560 by a Tibetan prince named Rinpungpa.

One cold winter day, I drew out a rare copy of the prince’s letter from the closed stacks of the New York Public Library. The manuscript, written in medieval Tibetan, was printed on long, loose-leaf pages that mimicked the palm leaves used in ancient Buddhist books. I had brought a red-robed monk, a young Tibetan from Staten Island, to attempt a translation, and when I unwrapped the book in his presence, a crowd of hushed bibliophiles gathered to watch.

Rinpungpa was surrounded by enemies, his world collapsing. Buddhism was no longer practiced in India, its land of birth, and Islam had conquered Afghanistan to the west and the Central Asian steppe to the north. Rinpungpa’s own clan had ruled brutally, and the prince correctly surmised that his days were limited. Seeking help, he summoned a spirit messenger to reach the enlightened kingdom, where his own father would be waiting, reborn in paradise.

Take this message and go to my father in Shambhala. May my words of truth, conquering the mountains of dualism, guide you along the way and help you to overcome the obstacles that lie before you.

Rinpungpa filled long passages with colorful accounts of the route across Tibet and Central Asia, warning of everything from starvation to forests made of knives to rivers so cold they killed you at first touch. Adding in the Tengyur and the other ancient texts, the directions pretty much boiled down to this: Go from the lowland Indian river valleys where the Lord Buddha lived, up to Kathmandu’s ancient kingdoms, and climb onto the roof of the world, crossing Tibet westward, via its greatest monasteries and the sacred mountain of Kailas. Then head north, over an “outer ring” of sky-high ice mountains, across a vicious desert, past jade city-states, into unknown vistas. All the while you must appease dozens of gods, accumulate merit and fend off monsters, suppress the demons of delusion and transcend mere xistence, recite 99 million mantras and fly through the sky on a fire chariot, only to reach an “inner ring” of snowy mountains so high that even an eagle cannot cross. Beyond there, you must choose rightly among high valleys and low cities, having the good sense to know Shambhala when you reach it.

Using the ancient texts, and Google Earth, I calculated this at 3,400 miles. Rinpungpa’s letter would lead me through three countries, a dozen languages, and many peoples, past the world’s highest mountains and down into the bottom of the lowest desert in Asia.

Six weeks, I told my wife. All the way to heaven, and then home.

Perhaps I would not make it; perhaps I would fail in some, or every, way. But one must go oneself to know the truth.

I DROPPED OFF THE TRAIN before Gorakhpur, walked over the border into Nepal, and paid my respects to Lord Buddha at his birthplace in Lumbini. According to Manlungpa, the 13th-century lama, the next stop was to visit “the Queen of Khom Khom,” a reference to a ninth-century ruler in what is now Bhaktapur, just across a broad, polluted valley from modern-day Kathmandu. Unless one of Nepal’s new Indian-style traffic jams is in force, it’s a 25-minute ride out to Bhaktapur, and I knocked off the queen’s stomping grounds on my first, rainy morning in the capital.

The next day, the Irish photographer Seamus Murphy flew in from Kabul. Seamus is strong as an ox, my partner on many expeditions, but he immediately collapsed in bed from heatstroke. Pale, sweating, he vomited up his food and spent the day moaning, wrapped in a blanket in a dark room. He sipped the electrolyte cocktails I mixed him and pleaded for time.

There is no sweeter place to be stranded than Kathmandu. For days I wandered the city, awash in temples mixing Hindu and Buddhist images, a porous culture capable of transmitting prophecies in any direction. Yet Shambhala was almost forgotten here. The city’s swankest hotel, the Shangri-La, is named instead for the imaginary paradise, invented by English author James Hilton in his 1933 novel, Lost Horizon, that has supplanted and confused the identity of Shambhala. The hotel did have a Shambhala Garden Café, and its Lost Horizon bar served a frothy pineapple-and-rum drink called the Shambhala, which research demonstrated was yummy.

The waiter screwed up his eyes when I asked where Shambhala was. “It means ‘garden,'” he said at last. “Beautiful garden in mountains. Shambhala is secret place for kings and lamas. Is a Tibet word.”

A clerk at the city’s biggest bookstore fared less well. “Shambhala,” he said, and started flipping through CDs. “This is Brazilian dance?”

I bought $45 worth of dehydrated soup, Snickers bars, cheese, peanut butter, honey, tuna, sugar, Nescafé, orzo, party balloons, books, cashews, burgundy, and Diamox for altitude, and we were ready to go. At dawn on the fourth day in Kathmandu, I hiked up to the Monkey Temple, Swayambhunath, a forested hilltop shrine shared by Hindus and Buddhists. The trinket vendors hadn’t even arrived, nor had the smog of traffic jams. Off in the woods, I noticed a body swinging from a tree.

Some Nepalis stood around, looking at the corpse. Lots of people kill themselves at the Monkey Temple, a man told me, because it was holy, and the closest forest to downtown. “There was a woman yesterday,” he explained. Everyone tried to hide their emotions, in the Nepali way.

While alive, the suicide had been poor, desperate, and apparently shoeless. Now a rope was cutting into his throat. Suffering, Buddha taught, is the nature of this world. Maybe this man would be reborn in Shambhala someday; according to Tibetan practice, the “long path” of earning merit over many lifetimes was the surest way to reach the kingdom.

The next morning, Seamus and I continued our journey by more conventional means, rolling out of Kathmandu in a tourist-agency 4×4. It was late July. The drive to the Tibetan border should have taken two hours, but there were six roadblocks, most of them just lines of rocks laid over the road by absentee protesters. These we moved aside; we joined a busload of Indian pilgrims in hauling away two tree trunks and, twice, leaped over burning tires, carrying our luggage through polite mobs demanding government jobs. On the far side of each roadblock, a new economy of taxis had sprung up; at one point we swapped drivers and cars with some Swiss tourists coming downhill.

Fending off demons took time, however, and it was six hours before we reached the frontier of China, in a narrow canyon the Tibetans call Hell’s Gate, the abrupt dropping-off point into the fiery lowlands. Our elaborately obtained group tourist visas were scrutinized in detail by the Chinese police. We couldn’t tell them the truth, that we were journalists; reporters are required to travel on short, heavily restricted itineraries with government minders. We couldn’t tell them that we planned to ditch our mandatory “guide,” that we’d be photographing Chinese military deployments in sensitive border regions, or that we would exit the Tibet Autonomous Region to the north, violating our visa by crossing Xinjiang Uygur province to Kazakhstan. Being turned back, or forcibly expelled, was always a possibility.

Good citizens, we stood in line, mute. Just before nightfall, we got our passport stamps and walked over a bridge, into the real journey. In a dismal hotel, we shared a celebratory bottle of wine with two Spaniards. It was a decent Chinese red called Great Wall (the 1999 and 2000 vintages are best). We were in Tibet.

It was cold, 11,000 feet, and I slept poorly. I kept seeing the body, swinging very slightly in the breeze. Don’t go, the corpse whispered. It’s really more of an idea.

LATE THE SECOND NIGHT IN Tibet, we ground heavily up a gentle plain that seemed endless, finally crossing the Shung La pass, at 17,060 feet, where it was snowing, hard. By midnight we were 5,000 feet lower, sharing an icy motel room with our driver. It was a modern caravansary, the parking lot packed with the Toyotas and Mitsubishis of Lhasa travel agencies. Breakfast was conducted chiefly in Dutch.

That afternoon, we passed a sign for an airport, then some heavy-machinery dealerships, and then the driver began shouting: “Potala! Potala!” But all I could see were billboards for cell-phone companies and the Bank of China. My guidebook insisted that this first sighting of Lhasa would take my breath away, but the altitude had already done that, and I only glimpsed a sliver of dirty white monastery between ads.

I’d been prepared for the letdown by Patrick French, author of the brilliantly unromantic Tibet, Tibet, who describes the city all too accurately as another Chinese provincial capital of bath-tile constructions and strutting businessmen. The temples were those of Adidas and Nike; tanks paraded through the streets; Beijing had sent its usual gift of vast imperial avenues and train service. The infamously successful new rail line to Lhasa had just opened, bringing 300 or more people a day into the city once thought to be the most isolated on earth. The most common reaction was that of the Spaniards, whom we encountered one night in a hip Korean restaurant with subdued lighting. “Somos triste,” the hefty one hissed. We are sad. “We hate it,” the other admitted.

To the extent that we idealize a place, we impoverish it, reducing reality to a list of shortcomings. If I ever reached Shambhala, I’d probably be more crushed than the Spaniards.

Lhasa still has some Lhasa. The heart of the old Tibetan quarter is the great Jokhang temple, a magnificent whirlwind of prostrating pilgrims, chanting toddlers, old nomads tottering on canes, and Chinese tourists in Che Guevara T-shirts making clandestine cell-phone checks. Brutish dob dob monks, the security, used knotted cords to lash the legs of women in short skirts or anyone who hogged a shrine or fell asleep in a corner. The loose and happy mob circled the interior, clockwise, beneath a worn fresco of Shambhala. Under a single dim bulb I could see the king receiving tribute and dispensing justice from his throne, inside the city, inside the kingdom, which was hidden deep inside the two rings of snow mountains mentioned in prophecies. Below him, the armies of Shambhala rode forth to smash hordes of barbarians; an elephant scythed through the ranks of the deluded materialists.

In the warm and airy summer palace, which the Dalai Lama fled in 1959, there was another round painting of Shambhala, directly across from his final throne (although, in his private bedroom, the young man preferred a lithograph of three cute kittens). And, finally, in the frigid and dark Potala, the winter palace, a monk led me to a dirty wall painting of the kingdom, partly hidden by a chest of drawers that might have held the DL’s socks and undies. Here the army of Shambhala was vast, a huge array of horse archers riding out to destroy some enemy hiding behind the dresser.

The Dalai Lama is an unprecedented popularizer of the Shambhala prophecy, teaching Kalachakra doctrines to tens of thousands in mass initiatations all over the globe. A world weary of synthetic Shangri-La has responded, giving the ancient legend New Age life. Seamus and I had checked in to the House of Shambhala, a boutique hotel full of red draperies and hot-stone massage therapy owned by a lean American financier named Laurence Brahm, who’d left behind a Hong Kong career to pursue his own 21st-century quest for Shambhala. An ascetic hedonist, Brahm slept on the roof (I almost stepped on him, heading to my dawn meditations) but surrounded himself with beautiful women and the comforts of his hotel.

Fluent in both Tibetan and Mandarin, Brahm had written a book on Shambhala. By his radically simplified accounting, Shambhala will remain hidden during the rules of 25 kings, each lasting one century. Since the Buddha was born about 2,500 years ago, Brahm argues that our present times are the end of the world. Waving the latest casualty counts from Iraq, he referred me to the Mahabharata:

Property will alone confer rank.

Wealth will be the only source of devotion.

Passion will be the sole bond of union between sexes.

Falsehood will be the only means of success in litigation.

That did sound familiar.

Brahm was part of a noble tradition of Westerners seeking revelation in Shambhala, one that ran back to the 1620s, when Jesuit missionaries climbed up from India, chasing reports of a powerful kingdom they called “Xambala.” By 1880, the seekers had hit New York, in the person of Madame Helena Blavatsky, a Russian spiritualist claiming to be in secret communication with the kings of Shambhala. Her disciple Nicholas Roerich, an eccentric painter, tried twice to reach the kingdom—once, in 1925, outfitted by Abercrombie & Fitch, and again, in 1934, on a hunt for “drought-resistant grasses” funded by a secret backer at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. F.D.R. took some heat for what would come to be known as the Guru Scandal, while Roerich blithely carried on, spotting UFOs and eventually declaring a mountain in Kazakhstan to be Shambhala.

Today dozens of Web sites and volumes propound theories linking Shambhala to Atlantis and the “real” builders of the pyramids. The most ridiculous of this genre is also the most popular: an execrable follow-up to James Redfield’s bestseller The Celestine Prophecy called The Secret of Shambhala, in which a groovy, energy-emitting Westerner rescues the world from apocalypse by meditating his way to the hidden kingdom.

At night, on the hard beds of the House of Shambhala, I attempted my own groovy energy emitting. Dream travel is a recognized way of reaching Shambhala (the “Great Fifth” Dalai Lama had a dream in which a dancing girl showed him the way), and before leaving home I had assembled a Dream Team of eight completely serious women, including my wife, several college friends, an ex-girlfriend fond of reading my tarot cards, and a professional dream interpreter, Gordana, who held sway over the coven. For three consecutive nights in Lhasa, Gordana instructed, I was to imagine myself on the roof of the Jokhang. The Dream Team would meet me there, sometime after midnight, also dreaming, and together we would try to head off to Shambhala.

All three nights, I slept like a hammer in the thin air. I had one brief vision, of a woman not my wife, and then, my stomach rolling with hunger, dreamed that I was opening our last can of tuna from Kathmandu. No sign of my wife. Or my ex-girlfriend.

It didn’t matter. Everybody declared the experiment a success, sort of, and we moved on.

WE ROLLED WEST TO THE CITY of Shigatse, a brilliant journey in warm sunshine, along the last paved roads we would see until the Kunlun Shan, the range on Tibet’s northern edge, almost a month later. Shigatse is Tibet’s second city, spiritually speaking, home of the powerful Tashilhunpo monastery and seat of the Panchen Lama, the Dalai Lama’s sometime rival. Tashilhunpo’s library was the original source of lonely Prince Rinpungpa’s letter and a clear way station on our journey. If you took out all of the prince’s mantras and meditations, all his rambling symbolism and theological poetry—that is, if you removed the inner journey to an interior Shambhala—then he gave some pretty clear directions from here on out. From Shigatse:

Turn to the north and west and take the high plateau to the sacred mountain of Kailas … From Kailas continue northwest to Ladakh … wind north through a maze of treacherous mountains … come out in the land of the Paksik, horsemen who wear white turbans and quilted robes filled with cotton … a barren desert devoid of water will stretch away before you like the desolate paths of suffering that run through this world of illusion.

That’s about how it went. We had a Land Cruiser and driver and no intention of returning to Lhasa, as our visas required. Tibet swallowed us, day after day spent pounding over steep ranges and sleeping in roadside tents on icy plains. We saw hardly a soul: It was August, and the nomads, with their black tents and colorful costumes, were off in the highest pastures. I counted fewer than ten horses in ten days.

Finally we entered a wider, higher plain, a naked and sere landscape of barren beauty, the dry, crystalline grandeur of the west. Days were a progression of rotten villages, spitting rain, and, everywhere, endless gangs of road workers, China’s new money tearing up the plateau for new roads, bridges, mines, and security posts. In one dumpy garrison town of thin air, karaoke bars, and “beauty parlors” (a euphemism for what Seamus called “knocking shops”), I stopped to use the last phone we’d see for a while, hoping to reach my wife.

A pretty Englishwoman, about 40, took the booth next to mine. She dialed her travel agent in London: “I just felt I had to call and let you know what is happening, yes, it’s horrible really, just awful, it’s just been a huge disappointment, the guide is terrible, all he does is sleep, or lie to us, the other people are all right but I’m just tired of the games, really, the flirting, I don’t think people came here for the right reason, really, everyone is trying to rip us off, or lie to us, all day every day, and I’m just fed up, it’s not what I expected, the guide is just trying to get sex from tourists, he won’t keep his hands off me, and he told everyone, ‘Don’t tell Jerry,’ because he already slept with Rebecca, who is married to Jerry, and so we are supposed to cover up for him, which I won’t, it’s not right.”

Tourism was in a get-rich-quick phase, the Tibetans unhinged by the soaring wealth around them, the Chinese pushing deeper everywhere, always. On day 30 of the trip, 1,300 miles in and well behind schedule, we were approaching the holy mountain of Kailas when we saw a Japanese woman standing in the road, tears streaming down her face. Circling Kailas is supposed to bring great merit, but it hadn’t worked for the Japanese girl, named Ona. She’d been dumped by her boyfriend and then robbed at a hotel while trying to hitchhike back to Lhasa. She’d lost her passport, her money, and her faith. Some Hindu pilgrims were feeding her; now we drove her back to the hotel, but the housemaids called her a whore and a liar, and then threw fistfuls of pebbles at her.

We dropped Ona at a police station and, as we pulled away, I gave her $200 in an envelope, with my return address. The way to Shambhala is “born from your store of merit,” Rinpungpa says.

Our oxygen intake was at 68 percent of normal when we reached Darchen, the town at 15,090 feet that serves as an ugly base camp for the pilgrimage around Kailas. Leaving our driver and picking up a teenage porter, we hiked the 32-mile route in three days, going counterclockwise around the black, snow-stained mountain. Traffic was light; our first day, we saw only a few ragged Buddhist pilgrims, one group of orange-clad Hindus on horseback, four Americans in tents, and a single, mute white woman gleefully spinning a prayer wheel. We slept in a monastery of the Nyingma, or Ancient Ones, the original Buddhists of Tibet. Like the monk on the train, the abbot, a high reincarnation, discouraged me from continuing on. Meditate more, he said, feeding me balls of yak butter mixed with tsampa, or barley flour, from his own fingertips. “Think only of others and you may reach Shambhala someday.” I would have preferred some outright encouragement, but when I pressed, the abbot burst into song.

We walked in the company of the wildest creatures we would see in Tibet: five tall, handsome nomads in brocaded robes, leading packhorses covered with bells. The women had braided their hair with cockle shells, coral, jade, and silver. The men wore sheepskin coats, laughed easily, and had no idea what a dried apricot was. We were all shy, each party awed by the other.

Together we crossed the notorious 18,370-foot Dolma La pass, a place of symbolic rebirth. A lammergeier, one of the immense carrion birds found at Tibetan sky burials, glided overhead, mocking our heaving lungs as Seamus and I, ignoring the warning that powerful demons guarded the pass, sat down to a meal of Danish luncheon meat and Nepali cheese. The nomads went on, their horses jingling; lower down, by the greenish Lake of Compassion, we would pass them taking tea. One long day downhill, through icefields and under rainbows, another night, and we were back in Darchen, with its massage parlors and rancid hotels.

We had slain the demons of desire with our swords of wisdom, laid ignorance low with our overwhelming compassion, and achieved the special knowledge of wet feet. We celebrated in a restaurant with good whiskey and a memorable array of Sino-Tibetan specialties:

Qancakes, banana pizza, Hide the Meal, Wood Ear Meat Thread, Laph Meat, Big Disk Chicken, Muslim Noodles with Pork, Amorous Feelings Beef Tenderloin.

Sic!

But the joke was on me. That evening, my money belt disappeared from the hotel, probably as I dozed near the iron stove. The holy mountain seemed to mock people like me, unserious materialists who were merely passing by.

That said, it works, this karma thing. About a month after the trip was over, I received a Japanese postal order for $200. If I had given Ona all of my money, I would still have it today.

AT KAILAS, WE LEFT the tourist route, heading north where the others turned east, back toward Lhasa. Our journey had barely begun. For days we rolled through long valleys, over the soda plains of highest, remotest Tibet, toward the Kunlun Shan, where the plateau fell into China’s Central Asian deserts. Between us and paradise lay the Aksai Chin, one of the least-known places on earth, an immense and uninhabited grassland at 11,000 feet. Nanda Devi, at 25,645 feet, shone brilliant white, perhaps 60 miles away. We passed K2, hidden by closer peaks. The view was still impressive, a sky-long chain of jagged mountains under a perfect blue heaven. Pay no attention to those who say the world is shrinking.

The Aksai Chin is a closed military zone. Still claimed by India, the territory is firmly in Chinese control, as we discovered one snowbound dawn when military police in Chinese jeeps shoved us off the road. An entire Chinese infantry division appeared: 3,000 or more men, brilliantly equipped, in a convoy of 300 trucks, pulling howitzers and antiaircraft guns, and escorted front and back by scores of SUVs containing suspicious officers. This was the Xinjiang Division, according to our stalwart driver, a careful Tibetan who knew full well that we were reporting without press visas (and wisely insisted on anonymity). For the next two days we tangled with this army convoy, passing parts of it, getting turned back, overtaking it again, driving through open desert to flank the troops, and then being turned back yet again. Finally we caught the entire convoy eating lunch and, relying on our store of merit and blazing smiles, drove right through a host of screaming MPs.

The days on the Aksai Chin were indistinguishable, a stream of 16-hour road marathons, sudden whiteouts, and 2 A.M. negotiations with truck drivers over towing fees. We were rubbed raw and lean, feeling that curious mixture of numbness and heightened senses, of discomfort and revelation, that causes you to value a single sunset while traveling—a final narrow ribbon of blood orange, dividing a black range of peaks from the dark night above—more than all the sunsets you have known at home. With life reduced to transitory essentials, we approached the state of mind of the old caravan routes, close enough to smell the camels, able to glimpse something of the ancient and alien journey laid out by Rinpungpa and others.

To get to Shambhala you still have a long road ahead …

Ed Bernbaum argued convincingly that the Kunlun Shan could be the “outer ring” of snow mountains that conceal Shambhala, the last barrier to the great desert mentioned in texts. Shambhala is also round, like this desert region, wrapped in a “circle” of ranges (the Kunlun Shan, the Tain Shan, and the Pamirs) that contained scores of Silk Road principalities, some of them specifically identified in the guides.

Home was now closer ahead than behind: After more than 2,000 miles of travel, the Kunlun Shan was the dividing point. It was my 41st day on the road, and we followed switchbacks up and down, through valleys no wider than a Frisbee toss, until we slipped beneath a great pendant mass of black rock covered with a scabbard of white snow, a terrible and despairing sight, even with a road to guide us through. It was hard to take such a mountain as mere metaphor, a symbol of some interior peak of the soul.

Whatever our difficulties in coming this far, they paled to nothing by historical standards. The Kunlun parted for the Toyota, hour by hour; all this road required was patience. We crossed three ranges and then, just as abruptly as we had climbed up onto the Tibetan Plateau, we fell off it. Between two peaks, I saw a long, brutal vista of endless waves of dunes, each giving off a snake of sand to the fierce winds. This was the Taklimakan, the western extension of the Gobi and by reputation the fiercest desert on earth. It wasn’t an idle reputation: Eighteen years before, I’d spent a hot month here with a Danish woman, scouring archaeological sites. The heat, the electrified dust storms, all the bad food and rough travel, the skin-cracking aridity of the Taklimakan, had been bearable only because I was blindly in love. In Uighur, the language of the Muslims here, Taklimakan means “Go in, don’t come out.” Everything I loathed in a 1,000-mile package.

At a leafy village full of white-capped Muslims, we crossed an internal border post. The snarling Han Chinese policeman was so busy mistreating the Tibetan truck drivers that he passed us into the Xinjiang Uygur region without a second look. At dusk, out on the plains, we saw the first oil rigs, topped by flaming beacons, and wove the Land Cruiser through our first herd of camels. These were double-humped Bactrian, Silk Road beasts with summer coats and clear eyes. The temperature had risen 40 degrees.

In the Tengyur guide, the oldest of all Tibetan sources on Shambhala, you are advised at this point to join a caravan to continue north. Writing eight centuries later, the third Panchen Lama warned: You will cross a place without water or people … It is desert … go for 21 days.

But we could go nowhere. For ten days, Seamus and I were entangled in the infamous Middle Kingdom bureaucracy, trying to extend our now violated visas. In Yecheng they said only Hotan could approve such things; in Hotan, Yutian; in Yutian, Korla. In three cases, we were denied an extension for a group visa by police officers standing beneath signs reading, in both English and Chinese, EXTENSION OF GROUP VISA 50 YUAN. In the welter of miscommunication, frustration, and freezing-cold police stations, I lost my sense of humor. (“SEAMUS!” I caught myself screaming at one point. “I. AM. TRYING. TO. SPEAK. CHI. NESE. GO. SIT. IN. THE. CAR.”)

The 13th-century lama Manlungpa had passed through the Kingdom of Li, famous for its jade. That was not hard to identify: The ancient jade markets of India, Nepal, and Tibet were all supplied by a single source, a riverbed outside modern Hotan. Mud walls were all that remained of Li, but hundreds of men, mostly Uighurs, were still working the riverbed for jade. They are the descendants of the Paksik mentioned by Rinpungpa, the horsemen in quilted cotton jackets and white turbans. The Uighurs have seen better days: Today they face much of the same religious and economic isolation as Tibetans, without the romantic figure of a Dalai Lama to give them a voice abroad. But in the first millennium, when they practiced Buddhism, they built the Silk Road into a wealthy and powerful network of trading oases and uncountable monasteries, where Buddhism, but also Christianity, Taoism, Islam, Manichaeism, and Zoroastrianism, were debated, studied, and transcribed into new languages. The Kalachakra teachings reflect knowledge of all these faiths.

With only two days left on our visa, we hired a taxi to sprint north, to Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang. The road was new, built by oil companies since my 1980s visit, and the fearsome Taklimakan yielded in 11 hours, not 21 days. It was a featureless wasteland, a hopeless ocean of heat that finally descended, on its northern edge, to marshland, and then the great cleaving river, the Tarim.

If the Kunlun Shan doesn’t look to you like the “outer ring” of snow mountains, and the jade kingdom of Li leaves you unconvinced, and the circular shape of this desert basin doesn’t reflect the lotus-like geography of Shambhala, and you somehow doubt the Taklimakan is the great spiritual desert that pilgrims must cross, still you must acknowledge the river. In all ancient accounts, the river that protects Shambhala flows east; the Tarim is the only major river in Central Asia that flows east. Wherever the kingdom lay, it was somewhere north of this river. We now left behind all maps.

I’VE SAID BEFORE THAT I’m not going to tell you where it is. That’s easy enough. Even when you’ve been there, you can’t say where you were, just as the third Panchen Lama predicted:

A person who travels the world looking for Shambhala cannot find it. But that does not mean it cannot be found.

The place itself—Ed Bernbaum’s likely prototype, the kingdom that Tibetans meant when they described Shambhala—sits out in the plain desert, at the very bottom of Asia, beneath sea level, in a heat sink that had melted me 18 years before. But it was cool and overcast when Seamus and I finally soared out of Urumqi, squeezed into a shared taxi for hours with three Uighur men reeking of alcohol. In a town that shall remain nameless, we switched transport, heading either southwest, or northeast, or some other direction, depending. Find your own way.

The kingdom provided a number of shocks when we finally reached it. It was of course the size of it that stunned us first. The city had been the richest in Asia in its heyday, and looked it: The enormous curtain walls of the outer fortress ran out through the haze for miles in a giant circle. They towered over us, cut with gates, formidable and imposing. Hundreds of buildings were still standing, some two stories high, in a warren of alleyways, temples, and inner palaces.

The biggest, brightest, most prosperous Buddhist kingdom, it seemed to have risen out of the sand, dispensing doctrines of mystery and fulfillment, and then vanished into the desert again. The city was converted to Islam in the 13th century, sacked by Mongols, then buried forever by European sailing ships that made the Silk Road irrelevant. Tibetans were left to worship a place that no longer existed.

Now nothing lived here, not even rats. No king or guardian deity greeted our arrival, only a ten-year-old boy who, even after we paid him, continued to badger us for money so relentlessly, so loudly, so unreasonably, that Seamus finally threw rocks at him. Soon we were left alone, the few tourists and guards departing with dusk.

@#95;box photo=image_2 alt=image_2_alt@#95;box

Throwing rocks at a child? Who was the demon here—him or us? We had wandered a whole long day in those ruins, in and out of palaces, through ancient gates, but only as we turned to leave at sunset did I have my second surprise. I had recognized nothing in this region, not even the nearest towns, but when I wandered into the old central palace, and looked up at the ceiling of the round reception room, my knees buckled as I saw that I had stood right here, in 1988. Never having heard of Shambhala, I’d gone there anyway. Too late, I saw that I had already made this pilgrimage. I was sent back, reeling, to those long days of hot bliss, our epic rides on steam trains through the desert, where whole kingdoms could wink in and out of history, appear in one spot and then another, their existence and location entirely dependent on memory, on stories written or retold. On that kind of map, there always had to be a perfect place, a Shambhala, whether or not its coordinates were known.

In falling darkness I found the southern gate of the city, slipped into a tunneled staircase, and came out atop the city walls. Digging in a hidden spot, I buried Rinpungpa’s letter. Take this message and go to my father in Shambhala. I tamped down the loose sand. Only now, at the end, could another journey begin.

IN THOSE ANCIENT TIMES, the Dane and I had ridden into the mountains, up past a lake, to the high summer pastures where the nomads lived. My horse was called Slowpoke, and hers Farter. It was an August to remember.

It was another year now, another life, and not even August any longer. Seven weeks on the road, overdue in other lands, we packed light and went on foot into the same mountains, the long, spearing range of the Tian Shan that runs from Kazakhstan into western China and which might qualify as the inner ring guarding Shambhala. For 18 years, I had needed to go back, to go beyond, to see one more valley. Rinpungpa urged me on:

Although you feel exhausted and sick from the rigors of the journey, hold on to your aim and continue.

Seamus led, and we walked fast, past the same lake I remembered from 1988, up toward the glaciers, and onward still, crossing into the narrow valleys where the nomads had been.

But the nomads were gone. Rings in the grass showed where their round tents had pressed down all summer. Ashes in their fire pits were undisturbed. We’d missed them by a day at most, perhaps only a few hours. In these high September peaks, snow was already in the air.

On a distant pass, we saw two men in dark clothes. They looked back at us, briefly, and then went over.

I tell you, I was there.