The Mahasiddha Kanhapa

(Krsnacarya), The Dark Siddha

Zealously practice generosity and moral conduct,

But you cannot attain siddhi supreme without a Guru

No more than drive a chariot without wheels.

The wide-winged vulture, innately skilled,

Glides high in the sky, ranging far away,

And the Guru's potent precepts absorbed

The karmically-destined yogin is content.

Born in the town of Somapuri Kanhapa, also known as Krsnacarya, was the son of a scribe. He took ordination in the great monastic academy of Somapuri, built by King Dharmapala. He was initiated into the mandala of the Deity Hevajra by his Guru Jalandhara.

Kanhapa practiced his sadhana for twelve years and was rewarded by a vision of Hevajra with his retinue while the earth trembled beneath him. This experience inflated his pride, but a Dakini appeared and warned him against any idea that this vision was anything but a preliminary sign on the path, assuring him that he had not yet realized ultimate truth. Kanhapa

continued his solitary practice, but one day, wishing to test himself, he placed his foot upon a rock and left his footprint in it. The Dakini appeared again, entreating him to return to his meditation seat. Again, sometime later, he awoke from his samadhi and found himself floating in space one cubit from the ground, and again the Dakini appeared, warning him of pride of achievement and pointing to his meditation seat. Finally it happened that he rose up with seven canopies floating above his head and seven damaru skull-drums spontaneously sounding in the sky around him.

"I have reached my goal," he told his disciples. "We will go to the barbarian island of Lankapuri to convert the inhabitants."

He set out for the city of Lankapuri on the island of Sri Lanka with a retinue of three thousand disciples. At the shore of the sea dividing the island from the mainland, wishing to impress his disciples and also the people of Sri Lanka, he left his attendants and began the crossing walking on the water.

"Even my Guru lacks this gift!" he thought to himself - and he sank into the sea. The current washed him ashore, and he found himself looking up at his Guru, Jalandhara, who was floating in the sky above him.

"Where are you going, Kanhapa?" asked his Guru. "What's the matter?"

"I was going to the barbarian island of Sri Lanka to save the people from the pitfalls of samsara, " Kanhapa replied meekly. "But on the way it occurred to me that my power was superior to yours, and the result was that I lost the power I had, and I sank into the sea."

"You do no one any good like that," Jalandhara commented. "You should go to my country of Pataliputra, where the beneficent King Dharmapala reigns, and there look for a pupil of mine who is a weaver. Obey him implicitly, and you will attain the ultimate truth, which you have not yet understood."

Kanhapa set out and, obeying his Guru, he found that his powers were restored. The canopies and damarus re-appeared in the sky, and he could walk upon water and leave footprints in rock. When he arrived at Pataliputra he left his three thousand disciples outside the city and went in search of the weaver. Walking down the main street of the town where the weavers had their shops, one by one he broke the threads of their looms with his gaze. As each began to retie his threads manually he knew he had to look further for his teacher. At the end of the street, on the outskirts of town, however, he found a weaver whose thread spontaneously re-wound itself, and he knew that he need look no further. Prostrating before this man, and circumambulating him, Kanhapa then besought him to teach the ultimate truth.

"Do you promise to obey me in all things?" inquired the weaver.

"I do," Kanhapa responded.

Then they walked together to the cremation ground, where they found a fresh corpse. "Can you cat the flesh of the corpse?" the weaver asked.

Kanhapa knelt down, took out his knife, and began to sever a piece of flesh.

"Not like that!" said the weaver with contempt, "Like this!" And he transformed himself into a wolf, leapt upon the corpse, and began to tear at it ravenously. Once more a human being he said, "You can only eat human flesh when you can transform yourself in that way."

Then continuing his instruction, he defecated and offered one oi the three pieces of his feces to his pupil. "Eat it!" he ordered.

"People will ridicule me if I do it," Kanhapa protested. "I shan't do it!"

Then the weaver ate one piece, the celestial gods ate another, and the third was carried off by the naga serpents to the nether world

After they had arrived back in the city the weaver bought five penny worth of food and alcohol. "Now call your disciples and we'll celebrate a communal ganacakra feast," he ordered.

Kanhapa did as he was told thinking, "There's not enough food there for even one man. How is he going to feed us all?"

When the communicants were assembled the weaver blessed the offerings and filled the bowls with rice, sweetmeats and every kind of delicacy. The feast lasted for seven days, and still the offerings had not all been consumed. "There is no end to this," Kanhapa eventually thought in disgust. "I am going," and he threw away his left overs as an offering to the hungry ghosts, called to his disciples, and walked off.

The weaver shouted after them:

Ah, you miserable children! You are destroying yourselves! You are the kind of yogins Who separate the emptiness of perfect insight From the active compassion of life! What will you gain by running away? Canopies and damarus are small achievements Meditate and realize the nature of reality!

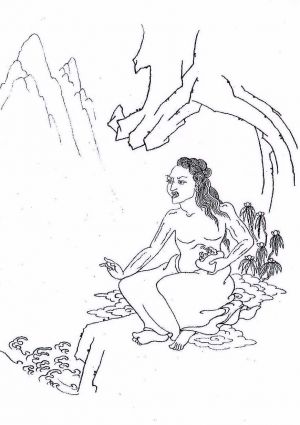

Kanhapa did not want to listen. He walked on, and travelled to the land of Bhadhokora, which was four hundred and fifty miles east of Somapuri. He stopped, finally, on the outskirts of the city, where he saw a young girl sitting beneath a lichee tree laden with fruit.

"Give me some fruit," he said to the girl.

"I will not," she replied.

The yogin was not to be denied, and he plucked the fruit from the tree with his powerful gaze. The girl sent each fruit back to the tree with an equally powerful look. Kanhapa was suddenly angry, and he cursed the girl with a maledictory mantra so that she fell writhing on the ground, bleeding from her limbs.

An indignant crowd gathered, "Buddhists are supposed to be kind," they muttered, "but this yogin is a killer!"

Kanhapa recollected himself when he heard these words, and feeling compassion for the girl he removed the curse. But he was now vulnerable to the curse that she called down upon him, and he fell down vomiting and excreting blood in an acute state of mortal anguish. He called the Dakini Bhande to him, and asked her to go to Sri Parvata Mountain in the south to bring the herbs that could cure him.

The Dakini departed, covering the six months’ journey to Sri Parvata in seven days. She soon found the herbs required and turned back to Bengal. On the last day of the return journey she passed an old crone weeping by the wayside, and failing to recognize the seductress who had cursed her master, she stopped to ask the cause of her distress.

"Isn't the death of the Lord Kanhapa sufficient cause to weep?" moaned the crone.

In despair Bhande threw the vital medicine away, only to find Kanhapa still critically ill, awaiting his cure. When he asked for the herbs she could only stammer her tale of deception.

Kanhapa had seven days to teach his disciples before finally leaving his karmically-matured body for the Dakini's Paradise. He taught them the sadhana called The Severed-headed Vajra Varahi.

After her master's death the Dakini Bhande sought the girl whose malediction had caused it. She searched the heavens above, the netherworld below, and the human world in between. Eventually she found her hiding in a sambhila tree. She dragged her out of it and cursed her with a spell from which she never recovered.

Kanhapa's story is the only legend that can be described as a cautionary tale. The other siddhas who failed to attain the ultimate mahamudra-siddhi - Goraksa, Caurangi, Khadgapa, among others - were treated very kindly by the narrator, but Mahapa, who performed a Hevajra sadhana and was recognized by the people as a Buddhist yogin, was heavily censured. He refused to listen to his Dakini advisor; he committed the cardinal sin of disobeying his Guru, the weaver; he was conceited and hasty; he was governed by anger and pride: he came to a nasty end. The weaver attributed his failings to his incomplete meditation; he

had not united insight and skillful means. In practical terms, although he may have attained prolonged periods of insight into emptiness in the controlled situation of trance, during his application of skillful means in an uncontrolled situation, when impediments such as inflated discursive thought and strong emotion arose, he lacked the perception of emptiness that would dissolve these obstacles. Thus, when he was provoked by the Dakini under the lichee tree, instead of donning a wrathful mask while maintaining the inner equilibrium and detachment that accompanies an understanding of all phenomena as empty colored

space, he was overcome by anger, and his belated contrition, which he could have reserved for a meditation of atonement, led to his death. Insight and skillful means are said to be like the wings of a bird; with only one wing, a bird cannot fly. As to emotion, so to thought; if his arrogant thoughts dissolved immediately they arose due to his perception of their emptiness, he would not have fallen. If he had been able to experience the sensual feast of the ganacakra as emptiness, his appetite would

have been limitless. If he had really eradicated his conditioned prejudice and preconceptions and gained the awareness of sameness, he could have eaten his Guru's excrement. If he had been free of a sense of ego, he could have transformed himself into a wolf and eaten human flesh. Kanhapa exemplifies the common phenomenon of the meditator who experiences the highest heavens in his meditative trance, who may have realized the emptiness of all things, and can even arise from his meditation

seat and remain in samddhi; but when called upon to act, the realization achieved in meditation vanishes. Likewise, when conditions are favorable he can demonstrate siddhi and fulfill his vow to assist all sentient beings, but when the ultimate insight is necessary to dissolve obstacles, due to vestiges of belief in "self' it is not available. Only siddhas have constant realization of the ultimate reality and live their daily lives with insight and skillful means united.

Three Dakinis feature in this legend; every Dakinis has the potential to function as a guide or assistant to liberation. The first Dakinis, who Kanhapa chose eventually to ignore, may have been a human embodiment or a sambhogakaya emanation. The Dakini under the fruit tree was a mundane Dakinis whose positive potential Kanhapa never discovered because she touched his ego, provoking him to compete and, fatally attached, he stirred in her a wrath that soon killed him. Clearly it is very difficult to

penetrate to the emptiness of a mundane Dakini when she shows the heavy and black side of her ambiguous nature; but if that is achieved she becomes a most loyal ally, guide and savioress. The third Dakinis, Bhande (or Bandhe), is his trustworthy friend who performed superhuman feats out of her devotion ~o him. Her name could mean "Buddhist Nun" (bandhd) or "Skull" (Mandha), which would associate her with the kapalikas. Kanhapa had a male disciple called Bhandepada (32), but it was a Bhadrapda (24) who sought the murderous Bahuri, found her in a tree in Devikotta and slew her, according to Taranatha.

Only in this legend are the practices of flesh-eating, dung-eating and (by implication) a literally performed ganacakra-puja mentioned. In these so-called left-handed (vamacara) practices there is an element of William Blake's "The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom," but more than that, it is in the basest impurity, in depravity and the lowest forms of life, and in tamasic food and drink, in the outcaste whore, the kapalika ascetic, excrement, corpses, alcohol, drugs, fish and meat, that the ultimate truth becomes accessible. Finding purity in impurity through the experience of the one taste of all things, the

ultimate sameness of all phenomena, which is emptiness, is realized. At the heart of depravity and corruption is the seed of innocence, unconditioned mind, which turns the wheel full circle and unites polarities. The seed grows into the flower of liberated bodhisattvic activities like a lotus growing out of the slime of a lake bottom: no slime, no lotus. The image of the lotus is basic and ubiquitous in tantric sadhana.

The stereotype of the flesh-eating, copulating, dung-eating tantrika is the kapalika ascetic, who consciously seeks the bottom of the pit of samsara to find his way to nirvana. The great poet and singer Kanhapa sings of the perfected kapalika in some of his many caryapada songs, and even identifies himself as a kapalika. His Guru Jalandhara was acknowledged as one of their great Gurus, but it is unlikely that Kanhapa himself actually took the Great Vow (mahavrata) and performed gross kapalika rites. Although he sings, "0 Dombi, I shall keep company with thee, and it is for this purpose that I have become a Kapali without aversion.... I am the Kapali and thou art the Dombi. For thee I have put on a garland of bones . . ." he also sings the subtle

metaphysical equations of the sahajiyas, and one is tempted to think that the Kapali (or kapalika) is for him a state of mind, and that he never practiced the literal interpretation. He sings of an uncompromising non-dual reality in which there is only empty space, and, simply by recognizing that, mahamudra-siddhi is attained. He rejects the intellectual approach, mantra and visualization, brahmin ritual, the kapalika’s attachment to tantric appearances and conventions, and he sings of the real kapalika as the ideal sahaja-siddha who has shaken off all prejudices and partiality, all preconceptions and doctrine, and realized "the ultimate principle of emptiness that arises spontaneously with every movement of the mind."

Historiography

Kanhapa is also a founder of nath lineages. Compared to others of the Five Naths he is not of primary importance, but the nath tradition is rich in anecdote concerning him. His status is defined by a story of Gorakhnath and Minanath giving a feast at which each selects his own dish. Kanhapa chose cooked snakes and scorpions and was hooted from the feast. It is said that he

was the son of the fisherman Kinwar, who caught Minapa's leviathan. The Kanipa, one of the twelve main panths, recognize him as adi-guru, as also the Augars, who perform twelve years of sadhana before initiation and lastly the Sepala, lesser, snake-charming yogins. It is as if he was patron-saint of the second-class naths. But he maintained a close relationship with Ja1andhara, his Guru, whom he rescued from inhumation.

"The Black One," "The Dark One," are names referring to skin color, not to moral quality. They are epithets given to dark-skinned aboriginals (adivasis), or nick-names given to a yogin of any caste. origin with a dark complexion. Different languages and dialects produced different forms of the name: Krsna, Kanhapa, Kahnapa, Kahnupa, Kanupa, Kanapa, Kanipa, etc., all translated into Tibetan as Nag po pa. Compounded with acarya (pandita or adept), Krsnacarya, Krsnacarin, Krsnacari, may become

just Caryapa; in Tibetan the Nag po spyod pa pa becomes simply sPyod pa pa. Since Tantra was a path that appealed to the outcaste tribals there must have been many Krsnas down the centuries. But apart from the nath siddha mentioned above, we are concerned principally with the two Kamacaryas of the tenth century who were probably Guru and disciple, and who are confounded

in our legend. Jalandhara was the Guru of the Father, Son and nath Kanhapas. The Father-Guru was an acarya, and it is likely that this Krsnacarya was responsible for most of the hundred and fifty works under this name, or variants, found in the Tenjur. It is uncertain whether the Father or the Son composed and sung the caryapada songs. The Son, who may have been the nath, could have sung "I am a Kapali free from aversion." But certainly the Son is associated with dance and small ritual drums known as damarus. Taranatha tells the story of the Son practicing the Samvara-tantra at Nalanda being induced by a goddess to go to

Kamarupa in Assam to gain the power of wealth (vasu-siddhi). In Kamarupa he found a chest containing an ornamented damaru, and the moment he picked it up his feet left the ground in dance. Whenever he played loudly five hundred siddha yogins and yoginis appeared and danced with him. This Kanhapa was an adept in the mother-tantra, and chronologically he was a contemporary of the nath founders. But was there another mahasiddha Kanha of this period? In Nepal a Lord Krsna taught Dza-Ham, and a brahmin Krsna taught Marpa Dopa. A later Krsna, also called Balin (Balinacarya), a disciple of Naropa, taught the Tibetans the Guhyasamaja-tantra.

As Father and Son Kanhapa are confounded in the Tibetan lineages it is almost impossible to relate the many disciples to their respective Gurus. Mekhala and Kanakhala (66 and 67), Kantali (69), Bhadrapa (24), and Kapalapa (72) received Hevajra initiation from a Kanhapa. Kugalibhadra and Vijayapada with their contemporary Guhyapada (Bhadrapa, who also received Kalacakra from a Krsna) were links in Kanhapa's Samvara lineage. Bhandepa (32) received the Guhyasamaja. Mahipa and Dharmapa (36 and 37) were also Kanhapa's disciples; and Tilopa (22) received Luipa's Samvara method from a Mahapa. Carpati (64) and Kapalapa (72) were affiliated with the naths, but the most renowned disciples of the nath Kanhapa were Gopicand and Bhatrnath, who even Taranatha acknowledges.

Source

[[1]]