The Saffron Conundrum: Disrobing Monks

Editor's Note: Should Buddhist monks seeking nirvana engage in politics and other worldly pursuits, like those in Burma recently did, or should they simply sit in meditation and not allow external happenings to distract them from the lofty goal they have set out for themselves? NAM editor Andrew Lam, author of Perfume Dreams, examines the issue, going back to the life of the Buddha.

Let’s begin with a Zen parable: Once there was an old lady who gives a Buddhist monk her little guesthouse to practice his meditation. She sends her maid to feed him daily and to clean his abode. After a few years she decides to test the monk to see how far he’s gotten in his practice. She tells her maid to ask the monk for a hug in return for all the work she has done for him. But he refuses. “Monks are not allowed to interact with women in this way,” he says. When the maid reports the incident to her employer, the old lady becomes upset and chases him out with a broom. “You haven’t learned a thing!” she yells.

One could, as the parable undoubtedly intends, interpret the story as how the monk is failing in his practice of compassion and in his quest to liberate himself; that he is too obsessed with form and less with essence. After all, how difficult is hugging someone who has been more than kind to you? And when, in the deepest Buddhist realization, there is no true self, who is monk and who is maid?

Yet, there is another side to this story: In his quest for enlightenment, should the monk be distracted by sensual persuasions? After all, Mara, the lord of illusion, also sent his daughters – Desire, Hatred, Ignorance – to seduce the future Buddha when he sat under the Bodhi tree trying to reach enlightenment. But the Buddha remained unmoved. Nor did Mara’s pestering him about his social duties as a father, son, husband, and prince of an entire kingdom have any effects on his quest for liberation. Nor did, for that matter, Mara’s threat to kill him with an army of demons.

In some ways, the parable is relevant to what’s happening to the monks in Myanmar in what The Economist magazine a few weeks earlier called the “Saffron Revolution.” Many of them took to the streets to protest the government’s massive spike of gas prices, and were subsequently arrested. There were reports of how the interrogators were yelling this phrase at the captive monks while beating them, “You are not a monk! You are not a monk!”

But then, what is a monk? And what are his duties to his fellow men?

Indeed, ever since the Buddha reached enlightenment and Buddhism was born, this has been an enduring conflict: to engage or not engage in the sensual world. For several weeks after he reached enlightenment, the Buddha remained in deep contemplation. He came to a sort of spiritual crossroads: should he stay in the forest or return to the world? He opted to stay in the forest and enjoy the fruits of his achievements in bliss until, as goes the story, Brahma Sahampati, the Lord of a Thousand Worlds, realized that if the Buddha remained silent the world would be deprived of the path to deliverance from suffering. He appeared before the Enlightened One, and humbly pleaded with him to teach the Dhamma "for the sake of those with dust in their eyes."

The Buddha, moved by compassion for the suffering beings, was persuaded to return to the world and taught what he knew.

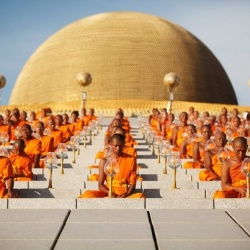

The order of monks and nuns who first followed the Buddha’s teachings were originally individuals who simply wanted to reach enlightenment and liberation. Protesting political crackdowns and a massive rise in fuel prices were not necessarily a part of the deal. There was no right or wrong either in the Buddha’s decision to return to the world. After all, it was said that there have been countless beings who reached enlightenment but chose not to return to the world of men. And the ultimate goal of Buddhism has always been personal liberation.

Yet, in practice, personal salvation has always been in conflict with the salvation of the world. Monks have set themselves on fire, engaged in public protests, even picked up arms over the centuries to fight for social justice and to protect their interests. As witnessed last September, the monks in various cities in Myanmar were indeed acting less monk-like when they organized street protests and engaged in confrontations with the governmental troops. Indeed, more than 10 high-ranking officials and military officers were held hostage by Buddhist monks for half a day in early September in Pokku township in northern Myanmar, while the monks set fire to their vehicles. They demanded the release of about 10 fellow monks arrested in a peaceful demonstration the day before, which was violently broken up by the authorities.

In the wake of the government crackdown that left hundreds killed and thousands arrested it was reported that many young monks in Myanmar have renounced their monkhood. The New York Times recently quoted a teacher in Myanmar talking about young monks who decided to disrobe. “Now the young monks that I talked to — who weren’t rounded up — they want to disrobe. They don’t have the moral courage to go on. ‘Better to be a layman,’ they said. I told them that this would be a terrible loss for our Buddhism. ‘No,’ they say, ‘What’s the use of meditation? The power of meditation can’t stop them from beating us.’ ”

Which begets these questions: What is the point of Buddhism in the face of political and social upheavals? How should the monks be judged in light of their pursuit of personal enlightenment? Are they selfish if they refuse to engage in the politics of the day? Does the path toward enlightenment lie in battles against the Burmese military police, or does it lie elsewhere? The price of engagement, of compassion, after all, can indeed be a terrible one if one is not spiritually resilient.

The Buddha did not see himself as a god but simply as a man who found a way toward liberation. He insisted that those who follow his teachings – the four noble truths and the eightfold path – test and verify the experience on their own. Since then, Buddhism has splintered into many schools of thought. The two main branches are Theravada and Mahayana, or sometimes known as southern or northern traditions. Both are complex traditions, but Theravada is the most popular form in Myanmar, and it puts a heavier emphasis on critical investigation and reasoning and social involvements instead of blind faith. There are therefore no easy answers to any of the Buddhist conundrums: Each monk has to enter that dark forest alone.

No doubt Buddhism and its message of compassion, inner peace, self-cultivation and self liberation will live long after the Junta and its terrible regime disappears from the landscape of Myanmar, but the age old conflict will also remain. Should the monk hug the pretty maid or not? Was he better off chased out and forced to go elsewhere in search of enlightenment? Or could he have found a way toward enlightenment amidst the sensual embrace?