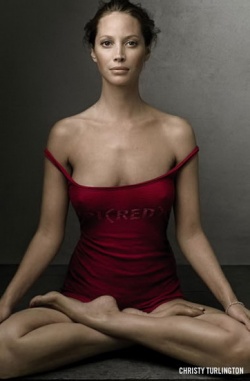

The Spirits of Chinese Religion

By Stephen F. Teiser:

The Spirits of Chinese Religion

image

from Donald S. Lopez, Jr , Religions of China in Practice, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996)

Acknowledging the wisdom of Chinese proverbs, most anthologies of Chinese religion are organized by the logic of the three teachings (_sanjiao_) of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Historical precedent and popular parlance attest to the importance of this threefold division for understanding Chinese culture. One of the earliest references to the trinitarian idea is attributed to Li Shiqian, a prominent scholar of the sixth century, who wrote that ``Buddhism is the sun, Daoism the moon, and Confucianism the five planets.<1> Li likens the three traditions to significant heavenly bodies, suggesting that although they remain separate, they also coexist as equally indispensable phenomena of the natural world. Other opinions stress the essential unity of the three religious systems. One popular proverb opens by listing the symbols that distinguish the religions from each other, but closes with the assertion that they are fundamentally the same: ``The three teach ings--the gold and cinnabar of Daoism, the relics of Buddhist figures, as well as the Confucian virtues of humanity and righteousness--are basically one tradition.<2> Stating the point more bluntly, some phrases have been put to use by writers in the long, complicated history of what Western authors have called ``syncretism. Such mottoes include ``the three teachings are one teaching; ``the three teachings return to the one; ``the three teachings share one body; and ``the three teachings merge into one.<3>

What sense does it make to subsume several thousand years of religious experience under these three (or three-in-one) categories? And why is this anthology organized differently? To answer these questions, we need first to understand what the three teachings are and how they came into existence.

There is a certain risk in beginning this introduction with an archaeology of the three teachings. The danger is that rather than fixing in the reader's mind the most significant forms of Chinese religion--the practices and ideas associated with ancestors, the measures taken to protect against ghosts, or the veneration of gods, topics which are highlighted by the selections in this anthology--emphasis will instead be placed on precisely those terms the anthology seeks to avoid. Or, as one friendly critic stated in a review of an earlier draft of this introduction, why must ``the tired old category of the three teachings be inflicted on yet another generation of students? Indeed, why does this introduction begin on a negative note, as it were, analyzing the problems with subsuming Chinese religion under the three teachings, and insert a positive appraisal of what constitutes Chinese religion only at the end? Why not begin with ``popular religion, the gods of China, and kinship and bureaucracy and then, only after those categories are established, proceed to discuss the explicit categories by which Chinese people have ordered their religious world? The answer has to do with the fact that Chinese religion does not come to us purely, or without mediation. The three teachings are a powerful and inescapable part of Chinese religion. Whether they are eventually accepted, rejected, or reformulated, the terms of the past can only be understood by examining how they came to assume their current status. Even the seemingly pristine translations of texts deemed ``primary are products of their time; the materials here have been selected by the translators and the editor according to the concerns of the particular series in which this book is published. This volume, in other words, is as much a product of Chinese religion as it is a tool enabling access to that field. And because Chinese religion has for so long been dominated by the idea of the three teachings, it is essential to understand where those traditions come from, who constructed them and how, as well as what forms of religious life are omitted or denied by constructing such a picture in the first place.

Confucianism

The myth of origins told by proponents of Confucianism (and by plenty of modern historians) begins with Confucius, whose Chinese name was Kong Qiu and who lived from 551 to 479 B.C.E. Judging from the little direct evidence that still survives, however, it appears that Kong Qiu did not view himself as the founder of a school of thought, much less as the originator of anything. What does emerge from the earliest layers of the written record is that Kong Qiu sought a revival of the ideas and institutions of a past golden age. Employed in a minor government position as a specialist in the governmental and family rituals of his native state, Kong Qiu hoped to disseminate knowledge of the rites and inspire their universal performance. That kind of broad-scale transformation could take place, he thought, only with the active encouragement of responsible rulers. The ideal ruler, as exemplified by the legendary sage-kings Yao and Shun or the adviser to the Zhou rulers, the Duke of Zhou, exercises ethical suasion, the ability to influence others by the power of his moral example. To the virtues of the ruler correspond values that each individual is supposed to cultivate: benevolence toward others, a general sense of doing what is right, loyalty and diligence in serving one's superiors. Universal moral ideals are necessary but not sufficient conditions for the restoration of civilization. Society also needs what Kong Qiu calls _li_, roughly translated as ``ritual. Although people are supposed to develop propriety or the ability to act appropriately in any given social situation (another sense of the same word, li), still the specific rituals people are supposed to perform (also li) vary considerably, depending on age, social status, gender, and context. In family ritual, for instance, rites of mourning depend on one's kinship relation to the deceased. In international affairs, degrees of pomp, as measured by ornateness of dress and opulence of gifts, depend on the rank of the foreign emissary. Offerings to the gods are also highly regulated: the sacrifices of each social class are restricted to specific classes of deities, and a clear hierarchy prevails. The few explicit statements attributed to Kong Qiu about the problem of history or tradition all portray him as one who ``transmits but does not create.<4> Such a claim can, of course, serve the ends of innovation or revolution. But in this case it is clear that Kong Qiu transmitted not only specific rituals and values but also a hierarchical social structure and the weight of the past.

The portrayal of Kong Qiu as originary and the coalescence of a self- conscious identity among people tracing their heritage back to him took place long after his death. Two important scholar-teachers, both of whom aspired to serve as close advisers to a ruler whom they could convince to institute a Confucian style of government, were Meng Ke (or Mengzi, ca. 371-289 B.C.E.) and Xun Qing (or Xunzi, d. 215 B.C.E.). Mengzi viewed himself as a follower of Kong Qiu's example. His doctrines offered a program for perfecting the individual. Sageliness could be achieved through a gentle process of cultivating the innate tendencies toward the good. Xunzi professed the same goal but argued that the means to achieve it required stronger measures. To be civilized, according to Xunzi, people need to restrain their base instincts and have their behavior modified by a system of ritual built into social institutions.

It was only with the founding of the Han dynasty (202 B.C.E.-220 C.E.), however, that Confucianism became Confucianism, that the ideas associated with Kong Qiu's name received state support and were disseminated generally throughout upper-class society. The creation of Confucianism was neither simple nor sudden, as three examples will make clear. In the year 136 B.C.E. the classical writings touted by Confucian scholars were made the foundation of the official system of education and scholarship, to the exclusion of titles supported by other philosophers. The five classics (or five scriptures, _wujing_) were the _Classic of Poetry_ (_Shijing_), _Classic of History_ (_Shujing_), _Classic of Changes_ (_Yijing_), _Record of Rites_ (_Liji_), and _Chronicles of the Spring and Autumn Period_ (_Chunqiu_) with the _Zuo Commentary_ (_Zuozhuan_), most of which had existed prior to the time of Kong Qiu. (The word _jing_ denotes the warp threads in a piece of cloth. Once adopted as a generic term for the authoritative texts of Han-dynasty Confucianism, it was applied by other traditions to their sacred books. It is translated variously as book, classic, scripture, and samutra.) Although Kong Qiu was commonly believed to have written or edited some of the five classics, his own statements (collected in the _Analects_ [_Lunyu_]) and the writings of his closest followers were not yet admitted into the canon. Kong Qiu's name was implicated more directly in the second example of the Confucian system, the state-sponsored cult that erected temples in his honor throughout the empire and that provided monetary support for turning his ancestral home into a national shrine. Members of the literate elite visited such temples, paying formalized respect and enacting rituals in front of spirit tablets of the master and his disciples. The third example is the corpus of writing left by the scholar Dong Zhongshu (ca. 179-104 B.C.E.), who was instrumental in promoting Confucian ideas and books in official circles. Dong was recognized by the government as the leading spokesman for the scholarly elite. His theories provided an overarching cosmological framework for Kong Qiu's ideals, sometimes adding ideas unknown in Kong Qiu's time, sometimes making more explicit or providing a particular interpretation of what was already stated in Kong Qiu's work. Dong drew heavily on concepts of earlier thinkers--few of whom were self-avowed Confucians--to explain the workings of the cosmos. He used the concepts of yin and yang to explain how change followed a knowable pattern, and he elaborated on the role of the ruler as one who connected the realms of Heaven, Earth, and humans. The social hierarchy implicit in Kong Qiu's ideal world was coterminous, thought Dong, with a division of all natural relationships into a superior and inferior member. Dong's theories proved determinative for the political culture of Confucianism during the Han and later dynasties.

What in all of this, we need to ask, was Confucian? Or, more precisely, what kind of thing is the ``Confucianism in each of these examples? In the first, that of the five classics, ``Confucianism amounts to a set of books that were mostly written before Kong Qiu lived but that later tradition associates with his name. It is a curriculum instituted by the emperor for use in the most prestigious institutions of learning. In the second example, ``Confucianism is a complex ritual apparatus, an empire-wide network of shrines patronized by government authorities. It depends upon the ability of the government to maintain religious institutions throughout the empire and upon the willingness of state officials to engage regularly in worship. In the third example, the work of Dong Zhongshu, ``Confucianism is a conceptual scheme, a fluid synthesis of some of Kong Qiu's ideals and the various cosmologies popular well after Kong Qiu lived. Rather than being an updating of something universally acknowledged as Kong Qiu's philosophy, it is a conscious systematizing, under the symbol of Kong Qiu, of ideas current in the Han dynasty.

If even during the Han dynasty the term ``Confucianism covers so many different sorts of things--books, a ritual apparatus, a conceptual scheme--one might well wonder why we persist in using one single word to cover such a broad range of phenomena. Sorting out the pieces of that puzzle is now one of the most pressing tasks in the study of Chinese history, which is already beginning to replace the wooden division of the Chinese intellectual world into the three teachings--each in turn marked by phases called ``proto-, ``neo-, or ``revival of--with a more critical and nuanced understanding of how traditions are made and sustained. For our more limited purposes here, it is instructive to observe how the word ``Confucianism came to be applied to all of these things and more.<5> As a word, ``Confucianism is tied to the Latin name, ``Confucius, which originated not with Chinese philosophers but with European missionaries in the sixteenth century. Committed to winning over the top echelons of Chinese society, Jesuits and other Catholic orders subscribed to the version of Chinese religious history supplied to them by the educated elite. The story they told was that their teaching began with Kong Qiu, who was referred to as Kongfuzi, rendered into Latin as ``Confucius. It was elaborated by Mengzi (rendered as ``Mencius) and Xunzi and was given official recognition-- as if it had existed as the same entity, unmodified for several hundred years--under the Han dynasty. The teaching changed to the status of an unachieved metaphysical principle during the centuries that Buddhism was believed to have been dominant and was resuscitated-- still basically unchanged--only with the teachings of Zhou Dunyi (1017- 1073), Zhang Zai (1020), Cheng Hao (1032-1085), and Cheng Yi (1033- 1107), and the commentaries authored by Zhu Xi (1130-1200). As a genealogy crucial to the self-definition of modern Confucianism, that myth of origins is both misleading and instructive. It lumps together heterogeneous ideas, books that predate Kong Qiu, and a state- supported cult under the same heading. It denies the diversity of names by which members of a supposedly unitary tradition chose to call themselves, including _ru_ (the early meaning of which remains disputed, usually translated as ``scholars or ``Confucians), _daoxue_ (study of the Way), _lixue_ (study of principle), and _xinxue_ (study of the mind). It ignores the long history of contention over interpreting Kong Qiu and overlooks the debt owed by later thinkers like Zhu Xi and Wang Yangming (1472-1529) to Buddhist notions of the mind and practices of meditation and to Daoist ideas of change. And it passes over in silence the role played by non-Chinese regimes in making Confucianism into an orthodoxy, as in the year 1315, when the Mongol government required that the writings of Kong Qiu and his early followers, redacted and interpreted through the commentaries of Zhu Xi, become the basis for the national civil service examination. At the same time, Confucianism's story about itself reveals much. It names the figures, books, and slogans of the past that recent Confucians have found most inspiring. As a string of ideals, it illuminates what its proponents wish it to be. As a lineage, it imagines a line of descent kept pure from the traditions of Daoism and Buddhism. The construction of the latter two teachings involves a similar process. Their histories, as will be seen below, do not simply move from the past to the present; they are also projected backward from specific presents to significant pasts.

Daoism

Most Daoists have argued that the meaningful past is the period that preceded, chronologically and metaphysically, the past in which the legendary sages of Confucianism lived. In the Daoist golden age the empire had not yet been reclaimed out of chaos. Society lacked distinctions based on class, and human beings lived happily in what resembled primitive, small-scale agricultural collectives. The lines between different nation-states, between different occupations, even between humans and animals were not clearly drawn. The world knew nothing of the Confucian state, which depended on the carving up of an undifferentiated whole into social ranks, the imposition of artificially ritualized modes of behavior, and a campaign for conservative values like loyalty, obeying one's parents, and moderation. Historically speaking, this Daoist vision was first articulated shortly after the time of Kong Qiu, and we should probably regard the Daoist nostalgia for a simpler, untrammeled time as roughly contemporary with the development of a Confucian view of origins. In Daoist mythology whenever a wise man encounters a representative of Confucianism, be it Kong Qiu himself or an envoy seeking advice for an emperor, the hermit escapes to a world untainted by civilization.

For Daoists the philosophical equivalent to the pre-imperial primordium is a state of chaotic wholeness, sometimes called _hundun_, roughly translated as ``chaos. In that state, imagined as an uncarved block or as the beginning of life in the womb, nothing is lacking. Everything exists, everything is possible: before a stone is carved there is no limit to the designs that may be cut, and before the fetus develops the embryo can, in an organic worldview, develop into male or female. There is not yet any division into parts, any name to distinguish one thing from another. Prior to birth there is no distinction, from the Daoist standpoint, between life and death. Once birth happens--once the stone is cut--however, the world descends into a state of imperfection. Rather than a mythological sin on the part of the first human beings or an ontological separation of God from humanity, the Daoist version of the Fall involves division into parts, the assigning of names, and the leveling of judgments injurious to life. _The Classic on the Way and Its Power_ (_Dao de jing_) describes how the original whole, the _dao_ (here meaning the ``Way above all other ways), was broken up: ``The Dao gave birth to the One, the One gave birth to the Two, the Two gave birth to the Three, and the Three gave birth to the Ten Thousand Things.<6> That decline-through-differentiation also offers the model for regaining wholeness. The spirit may be restored by reversing the process of aging, by reverting from multiplicity to the One. By understanding the road or path (the same word, dao, in another sense) that the great Dao followed in its decline, one can return to the root and endure forever.

Practitioners and scholars alike have often succumbed to the beauty and power of the language of Daoism and proclaimed another version of the Daoist myth of origins. Many pee a reality that exists independently of them. The _Zhuangzi_ is a much longer work composed of relatively discrete chapters written largely in prose, each of which brings sustained attention to a particular set of topics. Some portions have been compared to Wittgenstein's _Philosophical Investigations_. Others develop a story at some length or invoke mythological figures from the past. The _Zhuangzi_ refers to Laozi by name and quotes some passages from the _Classic on the Way and Its Power_, but the text as we know it includes contributions written over a long span of time. Textual analysis reveals at least four layers, probably more, that may be attributed to different authors and different times, with interests as varied as logic, primitivism, syncretism, and egotism. The word ``Daoism in English (corresponding to Daojia, ``the School [or Philosophy) of the Dao) is often used to refer to these and other books or to a free-floating outlook on life inspired by but in no way limited to them.

``Daoism is also invoked as the name for religious movements that began to develop in the late second century C.E.; Chinese usage typically refers to their texts as Daojiao, ``Teachings of the Dao or ``Religion of the Dao. One of those movements, called the Way of the Celestial Masters (Tianshi dao), possessed mythology and rituals and established a set of social institutions that would be maintained by all later Daoist groups. The Way of the Celestial Masters claims its origin in a revelation dispensed in the year 142 by the Most High Lord Lao (Taishang Laojun), a deified form of Laozi, to a man named Zhang Daoling. Laozi explained teachings to Zhang and bestowed on him the title of ``Celestial Master (Tianshi), indicating his exalted position in a system of ranking that placed those who had achieved immortality at the top and humans who were working their way toward that goal at the bottom. Zhang was active in the part of western China now corresponding to the province of Sichuan, and his descendants con tinued to build a local infrastructure. The movement divided itself into a number of parishes, to which each member-household was required to pay an annual tax of five pecks of rice--hence the other common name for the movement in its early years, the Way of the Five Pecks of Rice (Wudoumi dao). The administrative structure and some of the political functions of the organization are thought to have been modeled in part on secular government administration. After the Wei dynasty was founded in 220, the government extended recognition to the Way of the Celestial Masters, giving official approval to the form of local social administration it had developed and claiming at the same time that the new emperor's right to rule was guaranteed by the authority of the current Celestial Master.

Several continuing traits are apparent in the first few centuries of the Way of the Celestial Masters. The movement represented itself as having begun with divine-human contact: a god reveals a teaching and bestows a rank on a person. Later Daoist groups received revelations from successively more exalted deities. Even before receiving official recognition, the movement was never divorced from politics. Later Daoist groups too followed that general pattern, sometimes in the form of millenarian movements promising to replace the secular government, sometimes in the form of an established church providing services complementary to those of the state. The local communities of the Way of the Celestial Masters were formed around priests who possessed secret knowledge and held rank in the divine-human bureaucracy. Knowledge and position were interdependent: knowledge of the proper ritual forms and the authority to petition the gods and spirits were guaranteed by the priest's position in the hierarchy, while his rank was confirmed to his community by his expertise in a ritual repertoire. Nearly all types of rituals performed by Daoist masters through the ages are evident in the early years of the Way of the Celestial Masters. Surviving sources describe the curing of illness, often through confession; the exorcism of malevolent spirits; rites of passage in the life of the individual; and the holding of regular communal feasts.

While earlier generations (both Chinese bibliographers and scholars of Chinese religion) have emphasized the distinction between the allegedly pristine philosophy of the ``School of the Dao and the corrupt religion of the ``Teachings of the Dao, recent scholarship instead emphasizes the complex continuities between them. Many selections in this anthology focus on the beginnings of organized Daoism and the liturgical and social history of Daoist movements through the fifth century. The history of Daoism can be read, in part, as a succession of revelations, each of which includes but remains superior to the earlier ones. In South China around the year 320 the author Ge Hong wrote _He Who Embraces Simplicity_ (_Baopuzi_), which outlines different methods for achieving elevation to that realm of the immortals known as ``Great Purity (Taiqing). Most methods explain how, after the observance of moral codes and rules of abstinence, one needs to gather precious substances for use in complex chemical experiments. Followed properly, the experiments succeed in producing a sacred substance, ``gold elixir (_jindan_), the eating of which leads to immortality. In the second half of the fourth century new scriptures were revealed to a man named Yang Xi, who shared them with a family named Xu. Those texts give their possessors access to an even higher realm of Heaven, that of ``Highest Clarity (Shangqing). The scriptures contain legends about the level of gods residing in the Heaven of Highest Clarity. Imbued with a messianic spirit, the books foretell an apocalypse for which the wise should begin to prepare now. By gaining initiation into the textual tradition of Highest Clarity and following its program for cultivating immortality, adepts are assured of a high rank in the divine bureaucracy and can survive into the new age. The fifth century saw the canonization of a new set of texts, titled ``Numinous Treasure (Lingbao). Most of them are presented as sermons of a still higher level of deities, the Celestial Worthies (Tianzun), who are the most immediate personified manifestations of the Dao. The books instruct followers how to worship the gods supplicated in a wide variety of rituals. Called ``retreats (_zhai_, a word connoting both ``fast and ``feast), those rites are performed for the salvation of the dead, the bestowal of boons on the living, and the repentance of sins.

As noted in the discussion of the beginnings of the Way of the Celestial Masters, Daoist and imperial interests often intersected. The founder of the Tang dynasty (618-907), Li Yuan (lived 566-635, reigned 618-626, known as Gaozu), for instance, claimed to be a descendant of Laozi's. At various points during the reign of the Li family during the Tang dynasty, prospective candidates for government service were tested for their knowledge of specific Daoist scriptures. Imperial authorities recognized and sometimes paid for ecclesiastical centers where Daoist priests were trained and ordained, and the surviving sources on Chinese history are filled with examples of state sponsorship of specific Daoist ceremonies and the activities of individual priests. Later governments continued to extend official support to the Daoist church, and vice-versa. Many accounts portray the twelfth century as a particularly innovative period: it saw the development of sects named ``Supreme Unity (Taiyi), ``Perfect and Great Dao (Zhenda dao), and ``Complete Perfection (Quanzhen). In the early part of the fifteenth century, the forty-third Celestial Master took charge of compiling and editing Daoist ritual texts, resulting in the promulgation of a Daoist canon that contemporary Daoists still consider authoritative.

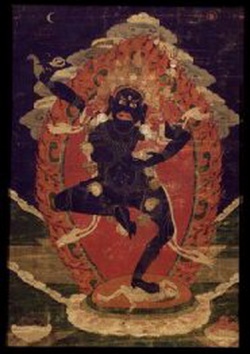

Possessing a history of some two thousand years and appealing to people from all walks of life, Daoism appears to the modern student to be a complex and hardly unitary tradition. That diversity is important to keep in mind, especially in light of the claim made by different Daoist groups to maintain a form of the teaching that in its essence has remained the same over the millennia. The very notion of immortality is one way of grounding that claim. The greatest immortals, after all, are still alive. Having conquered death, they have achieved the original state of the uncarved block and are believed to reside in the heavens. The highest gods are personified forms of the Dao, the unchanging Way. They are concretized in the form of stars and other heavenly bodies and can manifest themselves to advanced Daoist practitioners following proper visualization exercises. The transcendents (_xianren_, often translated as ``immortals) began life as humans and returned to the ideal embryonic condition through a variety of means. Some followed a regimen of gymnastics and observed a form of macrobiotic diet that simultaneously built up the pure elements and minimized the coarser ones. Others practiced the art of alchemy, assembling secret ingredients and using laboratory techniques to roll back time. Sometimes the elixir was prepared in real crucibles; sometimes the refining process was carried out eidetically by imagining the interior of the body to function like the test tubes and burners of the lab. Personalized rites of curing and communal feasts alike can be seen as small steps toward recovering the state of health and wholeness that obtains at the beginning (also the infinite ending) of time. Daoism has always stressed morality. Whether expressed through specific injunctions against stealing, lying, and taking life, through more abstract discussions of virtue, or through exemplary figures who transgress moral codes, ethics was an important element of Daoist practice. Nor should we forget the claim to continuity implied by the institution of priestly investiture. By possessing revealed texts and the secret registers listing the members of the divine hierarchy, the Daoist priest took his place in a structure that appeared to be unchanging.

Another way that Daoists have represented their tradition is by asserting that their activities are different from other religious practices. Daoism is constructed, in part, by projecting a non-Daoist tradition, picking out ideas and actions and assigning them a name that symbolizes ``the other.<7> The most common others in the history of Daoism have been the rituals practiced by the less institutionalized, more poorly educated religious specialists at the local level and any phenomenon connected with China's other organized church, Buddhism. Whatever the very real congruences in belief and practice among Daoism, Buddhism, and popular practice, it has been essential to Daoists to assert a fundamental difference. In this perspective the Daoist gods differ in kind from the profane spirits of the popular tradition: the former partake of the pure and impersonal Dao, while the latter demand the sacrifice of meat and threaten their benighted worshippers with ill ness and other curses. With their hereditary office, complex rituals, and use of the classical Chinese language, modern Daoist masters view themselves as utterly distinct from exorcists and mediums, who utilize only the language of everyday speech and whose possession by spirits appears uncontrolled. Similarly, anti-Buddhist rhetoric (as well as anti- Daoist rhetoric from the Buddhist side) has been severe over the centuries, often resulting in the temporary suppression of books and statues and the purging of the priesthood. All of those attempts to enforce difference, however, must be viewed alongside the equally real overlap, sometimes identity, between Daoism and other traditions. Records compiled by the state detailing the official titles bestowed on gods prove that the gods of the popular tradition and the gods of Daoism often supported each other and coalesced or, at other times, competed in ways that the Daoist church could not control. Eth nographies about modern village life show how all the various religious personnel cooperate to allow for coexistence; in some celebrations they forge an arrangement that allows Daoist priests to officiate at the esoteric rituals performed in the interior of the temple, while mediums enter into trance among the crowds in the outer courtyard. In imperial times the highest echelons of the Daoist and Buddhist priesthoods were capable of viewing their roles as complementary to each other and as necessarily subservient to the state. The government mandated the establishment in each province of temples belonging to both religions; it exercised the right to accept or reject the definition of each religion's canon of sacred books; and it sponsored ceremonial debates between leading exponents of the two churches in which victory most often led to coexistence with, rather than the destruction of, the losing party.

Buddhism

The very name given to Buddhism offers important clues about the way that the tradition has come to be defined in China. Buddhism is often called Fojiao, literally meaning ``the teaching (_jiao_) of the Buddha (Fo). Buddhism thus appears to be a member of the same class as Confucianism and Daoism: the three teachings are Rujiao (``teaching of the scholars or Confucianism), Daojiao (``teaching of the Dao or Daoism), and Fojiao (``teaching of the Buddha or Buddhism). But there is an interesting difference here, one that requires close attention to language. As semantic units in Chinese, the words Ru and Dao work differently than does Fo. The word Ru refers to a group of people and the word Dao refers to a concept, but the word Fo does not make literal sense in Chinese. Instead it represents a sound, a word with no semantic value that in the ancient language was pronounced as ``bud, like the beginning of the Sanskrit word ``buddha.<8> The meaning of the Chinese term derives from the fact that it refers to a foreign sound. In Sanskrit the word ``buddha means ``one who has achieved enlightenment, one who has ``awakened to the true nature of human existence. Rather than using any of the Chinese words that mean ``enlightened one, Buddhists in China have chosen to use a foreign word to name their teaching, much as native speakers of English refer to the religion that began in India not as ``the religion of the enlightened one, but rather as ``Buddhism, often without knowing precisely what the word ``Buddha means. Referring to Buddhism in China as Fojiao involves the recognition that this teaching, unlike the other two, originated in a foreign land. Its strangeness, its non-native origin, its power are all bound up in its name.

Considered from another angle, the word buddha () also accentuates the ways in which Buddhism in its Chinese context defines a distinctive attitude toward experience. Buddhas--enlightened ones--are unusual because they differ from other, unenlightened individuals and because of the truths to which they have awakened. Most people live in profound ignorance, which causes immense suffering. Buddhas, by contrast, see the true nature of reality. Such propositions, of course, were not advanced in a vacuum. They were articulated originally in the context of traditional Indian cosmology in the first several centuries B.C.E., and as Buddhism began to trickle haphazardly into China in the first centuries of the common era, Buddhist teachers were faced with a dilemma. To make their teachings about the Buddha understood to a non-Indian audience, they often began by explaining the understanding of human existence--the problem, as it were--to which Buddhism provided the answer. Those basic elements of the early Indian worldview are worth reviewing here. In that conception, all human beings are destined to be reborn in other forms, human and nonhuman, over vast stretches of space and time. While time in its most abstract sense does follow a pattern of decline, then renovation, followed by a new decline, and so on, still the process of reincarnation is without beginning or end. Life takes six forms: at the top are gods, demigods, and human beings, while animals, hungry ghosts, and hell beings occupy the lower rungs of the hierarchy. Like the gods of ancient Greece, the gods of Buddhism reside in the heavens and lead lives of immense worldly pleasure. Unlike their Greek counterparts, however, they are without exception mortal, and at the end of a very long life they are invariably reborn lower in the cosmic scale. Hungry ghosts wander in search of food and water yet are unable to eat or drink, and the denizens of the various hells suffer a battery of tortures, but they will all eventually die and be reborn again. The logic that determines where one will be reborn is the idea of _karma_. Strictly speaking the Sanskrit word karma means ``deed or ``action. In its relevant sense here it means that every deed has a result: morally good acts lead to good consequences, and the commission of evil has a bad result. Applied to the life of the individual, the law of karma means that the circumstances an individual faces are the result of prior actions. Karma is the regulating idea of a wide range of good works and other Buddhist practices.

The wisdom to which buddhas awaken is to see that this cycle of existence (_saymsmara_ in Sanskrit, comprising birth, death, and rebirth) is marked by impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and lack of a permanent self. It is impermanent because all things, whether physical objects, psychological states, or philosophical ideas, undergo change; they are brought into existence by preceding conditions at a particular point in time, and they eventually will become extinct. It is unsat isfactory in the sense that not only do sentient beings experience physical pain, they also face continual disappointment when the people and things they wish to maintain invariably change. The third characteristic of sentient existence, lack of a permanent self, has a long and complicated history of exegesis in Buddhism. In China the idea of ``no-self (Sanskrit: _anmatman_) was often placed in creative tension with the concept of repeated rebirth. On the one hand, Buddhist teachers tried to convince their audience that human existence did not end simply with a funeral service or memorial to the ancestors, that humans were reborn in another bodily form and could thus be related not only to other human beings but to animals, ghosts, and other species among the six modes of rebirth. To support that argument for rebirth, it was helpful to draw on metaphors of continuity, like a flame passed from one candle to the next and a spirit that moves from one lifetime to the next. On the other hand, the truth of impermanence entailed the argument that no permanent ego could possibly underlie the process of rebirth. What migrated from one lifetime to the next were not eternal elements of personhood but rather temporary aspects of psychophysical life that might endure for a few lifetimes--or a few thousand--but would eventually cease to exist. The Buddha provided an analysis of the ills of human existence and a prescription for curing them. Those ills were caused by the tendency of sentient beings to grasp, to cling to evanescent things in the vain hope that they remain permanent. In this view, the very act of clinging contributes to the perpetuation of desires from one incarnation to the next. Grasping, then, is both a cause and a result of being committed to a permanent self.

The wisdom of buddhas is neither intellectual nor individualistic. It was always believed to be a soteriological knowledge that was expressed in the compassionate activity of teaching others how to achieve liberation from suffering. Traditional formulations of Buddhist practice describe a path to salvation that begins with the observance of morality. Lay followers pledged to abstain from the taking of life, stealing, lying, drinking intoxicating beverages, and engaging in sexual relations outside of marriage. Further injunctions applied to householders who could observe a more demanding life-style of purity, and the lives of monks and nuns were regulated in even greater detail. With morality as a basis, the ideal path also included the cultivation of pure states of mind through the practice of meditation and the achieving of wisdom rivaling that of a buddha.

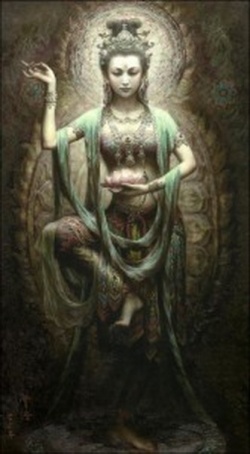

The discussion so far has concerned the importance of the foreign component in the ideal of the buddha and the actual content to which buddhas are believed to awaken. It is also important to consider what kind of a religious figure a buddha is thought to be. We can distinguish two separate but related understandings of what a buddha is. In the first understanding the Buddha (represented in English with a capital B) was an unusual human born into a royal family in ancient India in the sixth or fifth century B.C.E. He renounced his birthright, followed established religious teachers, and then achieved enlightenment after striking out on his own. He gathered lay and monastic disciples around him and preached throughout the Indian subcontinent for almost fifty years, and he achieved final ``extinction (the root meaning of the Sanskrit word _nirvana_) from the woes of existence. This unique being was called Gautama (family name) Siddh;amartha (personal name) during his lifetime, and later tradition refers to him with a variety of names, including Sakyamuni (literally ``Sage of the Sakya clan) and Tathagata (``Thus-Come One). Followers living after his death lack direct access to him because, as the word ``extinction implies, his release was permanent and complete. His influence can be felt, though, through his traces--through gods who encountered him and are still alive, through long-lived disciples, through the places he touched that can be visited by pilgrims, and through his physical remains and the shrines (_stupa_) erected over them. In the second understanding a buddha (with a lowercase b) is a generic label for any enlightened being, of whom Sakyamuni was simply one among many. Other buddhas preceded Sakyamuni's appearance in the world, and others will follow him, notably Maitreya (Chinese: Mile), who is thought to reside now in a heavenly realm close to the surface of the Earth. Buddhas are also dispersed over space: they exist in all directions, and one in particular, Amitayus (or Amitabha, Chinese: Amituo), presides over a land of happiness in the West. Related to this second genre of buddha is another kind of figure, a bodhisattva (literally ``one who is intent on enlightenment, Chinese: ). Bodhisattvas are found in most forms of Buddhism, but their role was particularly emphasized in the many traditions claiming the polemical title of Mahayana (``Greater Vehicle, in opposition to Hinayana, ``Smaller Vehicle) that began to develop in the first century B.C.E. Technically speaking, bodhisattvas are not as advanced as buddhas on the path to enlightenment. Bodhisattvas particularly popular in China include Avalokitesvara (Chinese: Guanyin, Guanshiyin, or Guanzizai), Bhaisajyaguru (Chinese: Yaoshiwang), Ksitigarbha (Chinese: Dizang), Manjusri (Wenshu), and Samantabhadra (Puxian). While buddhas appear to some followers as remote and all-powerful, bodhisattvas often serve as mediating figures whose compassionate involvement in the impurities of this world makes them more approachable. Like buddhas in the second sense of any enlightened being, they function both as models for followers to emulate and as saviors who intervene actively in the lives of their devotees.

The Three Jewels

In addition to the word ``Buddhism (Fojiao), Chinese Buddhists have represented the tradition by the formulation of the ``three jewels (Sanskrit: _triratna_, Chinese: _sanbao_). Coined in India, the three terms carried both a traditional sense as well as a more worldly reference that is clear in Chinese sources.<9> The first jewel is Buddha, the traditional meaning of which has been discussed above. In China the term refers not only to enlightened beings, but also to the materials through which buddhas are made present, including statues, the buildings that house statues, relics and their containers, and all the finances needed to build and sustain devotion to buddha images.

The second jewel is the dharma (Chinese: ), meaning ``truth or ``law. The dharma includes the doctrines taught by the Buddha and passed down in oral and written form, thought to be equivalent to the universal cosmic law. Many of the teachings are expressed in numerical form, like the three marks of existence (impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and no-self, discussed above), the four noble truths (unsatisfactoriness, cause, cessation, path), and so on. As a literary tradition the dharma also comprises many different genres, the most important of which is called _sutra_ in Sanskrit. The Sanskrit word refers to the warp thread of a piece of cloth, the regulating or primary part of the doctrine (compare its Proto-Indo-European root, *_syu_, which appears in the English words suture, sew, and seam). The earliest Chinese translators of Buddhist Sanskrit texts chose a related loaded term to render the idea in Chinese: _jing_, which denotes the warp threads in the same manner as the Sanskrit, but which also has the virtue of being the generic name given to the classics of the Confucian and Taoist traditions. Sutras usually begin with the words ``Thus have I heard. Once, when the Buddha dwelled at. . . . That phrase is attributed to the Buddha's closest disciple, Ananda, who according to tradition was able to recite all of the Buddha's sermons from memory at the first convocation of monks held after the Buddha died. In its material sense the dharma referred to all media for the Buddha's law in China, including sermons and the platforms on which sermons were delivered, Buddhist rituals that included preaching, and the thousands of books--first handwritten scrolls, then booklets printed with wooden blocks--in which the truth was inscribed.

The third jewel is sangha (Chinese: or ), meaning ``assembly. Some sources offer a broad interpretation of the term, which comprises the four sub-orders of monks, nuns, lay men, and lay women. Other sources use the term in a stricter sense to include only monks and nuns, that is, those who have left home, renounced family life, accepted vows of celibacy, and undertaken other austerities to devote themselves full-time to the practice of religion. The differences and interdependencies between householders and monastics were rarely absent in any Buddhist civilization. In China those differences found expression in both the spiritual powers popularly attributed to monks and nuns and the hostility sometimes voiced toward their way of life, which seemed to threaten the core values of the Chinese family system. The interdependent nature of the relationship between lay people and the professionally religious is seen in such phenomena as the use of kinship terminology--an attempt to re-create family--among monks and nuns and the collaboration between lay donors and monastic officiants in a wide range of rituals designed to bring comfort to the ancestors. ``Sangha in China also referred to all of the phenomena considered to belong to the Buddhist establishment. Everything and everyone needed to sustain monastic life, in a very concrete sense, was included: the living quarters of monks; the lands deeded to temples for occupancy and profit; the tenant families and slaves who worked on the farm land and served the sangha; and even the animals attached to the monastery farms.

Standard treatments of the history of Chinese Buddhism tend to emphasize the place of Buddhism in Chinese dynastic history, the translation of Buddhist texts, and the development of schools or sects within Buddhism. While these research agenda are important for our understanding of Chinese Buddhism, many of the contributors to this anthology have chosen to ask rather different questions, and it is worthwhile explaining why.

Many overviews of Chinese Buddhist history are organized by the template of Chinese dynasties. In this perspective, Buddhism began to enter China as a religion of non-Chinese merchants in the later years of the Han dynasty. It was during the following four centuries of disunion, including a division between non-Chinese rulers in the north and native (``Han) governments in the south as well as warfare and social upheaval, that Buddhism allegedly took root in China. Magic and meditation ostensibly appealed to the ``barbarian rulers in the north, while the dominant style of religion pursued by the southerners was philosophical. During the period of disunion, the general consensus suggests, Buddhist translators wrestled with the problem of conveying Indian ideas in a language their Chinese audience could understand; after many false starts Chinese philosophers were finally able to comprehend common Buddhist terms as well as the complexities of the doctrine of emptiness. During the Tang dynasty Buddhism was finally ``Sinicized or made fully Chinese. Most textbooks treat the Tang dynasty as the apogee or mature period of Buddhism in China. The Tang saw unprecedented numbers of ordinations into the ranks of the Buddhist order; the flourishing of new, allegedly ``Chinese schools of thought; and lavish support from the state. After the Tang, it is thought, Buddhism entered into a thousand-year period of decline. Some monks were able to break free of tradition and write innovative commentaries on older texts or reshape received liturgies, some patrons managed to build significant temples or sponsor the printing of the Buddhist canon on a large scale, and the occasional highly placed monk found a way to purge debased monks and nuns from the ranks of the sangha and revive moral vigor, but on the whole the stretch of dynasties after the Tang is treated as a long slide into intellectual, ethical, and material poverty. Stated in this caricatured a fashion, the shortcomings of this approach are not hard to discern. This approach accentuates those episodes in the history of Buddhism that intersect with important moments in a political chronology, the validity of which scholars in Chinese studies increasingly doubt. The problem is not so much that the older, dynastic-driven history of China is wrong as that it is limited and one-sided. While traditional history tends to have been written from the top down, more recent attempts argue from the bottom up. Historians in the past forty years have begun to discern otherwise unseen patterns in the development of Chinese economy, society, and political institutions. Their conclusions, which increasingly take Bud dhism into account, suggest that cycles of rise and fall in population shifts, economy, family fortunes, and the like often have little to do with dynastic history--the implication being that the history of Buddhism and other Chinese traditions can no longer be pegged simply to a particular dynasty. Similarly, closer scrutiny of the documents and a greater appreciation of their biases and gaps have shown how little we know of what really transpired in the process of the control of Buddhism by the state. The Buddhist church was always, it seems, dependent on the support of the landowning classes in medieval China. And it appears that the condition of Buddhist institutions was tied closely to the occasional, decentralized support of the lower classes, which is even harder to document than support by the gentry. The very notion of rise and fall is a teleological, often theological, one, and it has often been linked to an obsession with one particular criterion--accurate translation of texts, or correct understanding of doctrine--to the exclusion of all others.

The translation of Buddhist texts from Sanskrit and other Indic and Central Asian languages into Chinese constitutes a large area of study. Although written largely in classical Chinese in the context of a premodern civilization in which relatively few people could read, Buddhist sutras were known far and wide in China. The seemingly magical spell (Sanskrit: _dharani_) from the _Heart Sutra_ was known by many; stories from the _Lotus Sutra_ were painted on the walls of popular temples; religious preachers, popular storytellers, and low-class dramatists alike drew on the rich trove of mythology provided by Buddhist narrative. Scholars of Buddhism have tended to focus on the chronology and accuracy of translation. Since so many texts were translated (one eighth-century count of the extant number of canonical works is 1,124),<10> and the languages of Sanskrit and literary Chinese are so distant, the results of that study are foundational to the field. To understand the history of Chinese Buddhism it is indispensable to know what texts were available when, how they were translated and by whom, how they were inscribed on paper and stone, approved or not approved, disseminated, and argued about. On the other hand, within Buddhist studies scholars have only recently begun to view the act of translation as a conflict-ridden process of negotiation, the results of which were Chinese texts whose meanings were never closed. Older studies, for instance, sometimes distinguish between three different translation styles. One emerged with the earliest known translators, a Parthian given the Chinese name An Shigao (fl. 148-170) and an Indoscythian named Lokaksema (fl. 167-186), who themselves knew little classical Chinese but who worked with teams of Chinese assistants who peppered the resulting translations with words drawn from the spoken language. The second style was defined by the Kuchean translator Kumarajiva (350-409), who retained some elements of the vernacular in a basic framework of literary Chinese that was more polished, consistent, and acceptable to contemporary Chinese tastes. It is that style--which some have dubbed a ``church language of Buddhist Chinese, by analogy with the cultural history of medieval Latin--that proved most enduring and popular. The third style is exemplified in the work of Xuanzang (ca. 596-664), the seventh-century Chinese monk, philosopher, pilgrim, and translator. Xuanzang was one of the few translators who not only spoke Chinese and knew Sanskrit, but also knew the Chinese literary language well, and it is hardly accidental that Chinese Buddhists and modern scholars alike regard his translations as the most accurate and technically precise. At the same time, there is an irony in Xuanzang's situation that forces us to view the process of translation in a wider context. Xuanzang's is probably the most popular Buddhist image in Chinese folklore: he is the hero of the story _Journey to the West_ (_Xiyou ji_), known to all classes as the most prolific translator in Chinese history and as an indefatigable, sometimes overly serious and literal, pilgrim who embarked on a sacred mission to recover original texts from India. Though the mythological character is well known, the surviving writings of the seventh-century translator are not. They are, in fact, rarely read, because their grammar and style smack more of Sanskrit than of literary Chinese. What mattered to Chinese audiences-- both the larger audience for the novels and dramas about the pilgrim and the much smaller one capable of reading his translations--was that the Chinese texts were based on a valid foreign original, made even more authentic by Xuanzang's personal experiences in the Buddhist homeland.

The projection of categories derived from European, American, and modern Japanese religious experience onto the quite different world of tradit ideas shared by larger and less exclusive segments of the Chinese Buddhist community and on schools less well represented in other anthologies.

The Problem of Popular Religion

The brief history of the three teachings offered above provides, it is hoped, a general idea of what they are and how their proponents have come to claim for them the status of a tradition. It is also important to consider what is not named in the formulation of the three teachings. To define Chinese religion primarily in terms of the three traditions is to exclude from serious consideration the ideas and practices that do not fit easily under any of the three labels. Such common rituals as offering incense to the ancestors, conducting funerals, exorcising ghosts, and consulting fortunetellers; belief in the patterned interaction between light and dark forces or in the ruler's influence on the natural world; the tendency to construe gods as government officials; the preference for balancing tranquility and movement--all belong as much to none of the three traditions as they do to one or three. These forms of religion, introduced in more detail below, are the subject of numerous selections in this anthology.

The focus on the three teachings is another way of privileging precisely the varieties of Chinese religious life that have been maintained largely through the support of literate and often powerful representatives. The debate over the unity of the three teachings, even when it is resolved in favor of toleration or harmony--a move toward the one rather than the three--drowns out voices that talk about Chinese religion as neither one nor three. Another problem with the model of the three teachings is that it equalizes what are in fact three radically incommensurable things. Confucianism often functioned as a political ideology and a system of values; Daoism has been compared, inconsistently, to both an outlook on life and a system of gods and magic; and Buddhism offered, according to some analysts, a proper soteriology, an array of techniques and deities enabling one to achieve salvation in the other world. Calling all three traditions by the same unproblematic term, ``teaching, perpetuates confusion about how the realms of life that we tend to take for granted (like politics, ethics, ritual, religion) were in fact configured differently in traditional China.

Another way of studying Chinese religion is to focus on those aspects of religious life that are shared by most people, regardless of their affiliation or lack of affiliation with the three teachings. Such forms of popular religion as those named above (offering incense, conducting funerals, and so on) are important to address, although the category of ``popular religion entails its own set of problems.

We can begin by distinguishing two senses of the term ``popular religion. The first refers to the forms of religion practiced by almost all Chinese people, regardless of social and economic standing, level of literacy, region, or explicit religious identification. Popular religion in this first sense is the religion shared by people in general, across all social boundaries. Three examples, all of which can be dated as early as the first century of the common era, help us gain some understanding of what counts as popular religion in the first sense. The first example is a typical Chinese funeral and memorial service. Following the death of a family member and the unsuccessful attempt to reclaim his or her spirit, the corpse is prepared for burial. Family members are invited for the first stage of mourning, with higher- ranking families entitled to invite more distant relatives. Rituals of wailing and the wearing of coarse, undyed cloth are practiced in the home of the deceased. After some days the coffin is carried in a procession to the grave. After burial the attention of the living shifts toward caring for the spirit of the dead. In later segments of the funerary rites the spirit is spatially fixed--installed--in a rectangular wooden tablet, kept at first in the home and perhaps later in a clan hall. The family continues to come together as a corporate group on behalf of the deceased; they say prayers and send sustenance, in the form of food, mock money, and documents addressed to the gods who oversee the realm of the dead. The second example of popular or common religion is the New Year's festival, which marks a passage not just in the life of the individual and the family, but in the yearly cycle of the cosmos. As in most civilizations, most festivals in China follow a lunar calendar, which is divided into twelve numbered months of thirty days apiece, divided in half at the full moon (fifteenth night) and new moon (thirtieth night); every several years an additional (or intercalary) month is added to synchronize the passage of time in lunar and solar cycles. Families typically begin to celebrate the New Year's festival ten or so days before the end of the twelfth month. On the twenty-third day, family members dispatch the God of the Hearth (Zaojun), who watches over all that transpires in the home from his throne in the kitchen, to report to the highest god of Heaven, the Jade Emperor (Yuhuang dadi). For the last day or two before the end of the year, the doors to the house are sealed and people worship in front of the images of the various gods kept in the house and the ancestor tablets. After a lavish meal rife with the symbolism of wholeness, longevity, and good fortune, each junior member of the family prostrates himself and herself before the head of the family and his wife. The next day, the first day of the first month, the doors are opened and the family enjoys a vacation of resting and visiting with friends. The New Year season concludes on the fifteenth night (the full moon) of the first month, typically marked by a lantern celebration.

The third example of popular religion is the ritual of consulting a spirit medium in the home or in a small temple. Clients request the help of mediums (sometimes called ``shamans in Western-language scholarship; in Chinese they are known by many different terms) to solve problems like sickness in the family, nightmares, possession by a ghost or errant spirit, or some other misfortune. During the seance the medium usually enters a trance and incarnates a tutelary deity. The divinity speaks through the medium, sometimes in an altered but comprehensible voice, sometimes in sounds, through movements, or by writing characters in sand that require deciphering by the medium's manager or interpreter. The deity often identifies the problem and prescribes one among a wide range of possible cures. For an illness a particular herbal medicine or offering to a particular spirit may be recommended, while for more serious cases the deity himself, as dramatized in the person of the medium, does battle with the demon causing the difficulty. The entire drama unfolds in front of an audience composed of family members and nearby residents of the community. Mediums themselves often come from marginal groups (unmarried older women, youths prone to sickness), yet the deities who speak through them are typically part of mainstream religion, and their message tends to affirm rather than question traditional morality.

Some sense of what is at stake in defining ``popular religion in this manner can be gained by considering when, where, and by whom these three different examples are performed. Funerals and memorial services are carried out by most families, even poor ones; they take place in homes, cemeteries, and halls belonging to kinship corporations; and they follow two schedules, one linked to the death date of particular members (every seven days after death, 100 days after death, etc.) and one linked to the passage of nonindividualized calendar time (once per year). From a sociological perspective, the institutions active in the rite are the family, a complex organization stretching back many generations to a common male ancestor, and secondarily the community, which is to some extent protected from the baleful influences of death. The family too is the primary group involved in the New Year's celebration, although there is some validity in attributing a trans-social dimension to the festival in that a cosmic passage is marked by the occasion. Other social spheres are evident in the consultation of a medium: although it is cured through a social drama, sickness is also individuating; and some mediumistic rituals involve the members of a cult dedicated to the particular deity, membership being determined by personal choice.

These answers are significant for the contrast they suggest between traditional Chinese popular religion and the forms of religion characteristic of modern or secularized societies, in which religion is identified largely with doctrine, belief about god, and a large, clearly discernible church. None of the examples of Chinese popular religion is defined primarily by beliefs that necessarily exclude others. People take part in funerals without any necessary commitment to the existence of particular spirits, and belief in the reality of any particular tutelary deity does not preclude worship of other gods. Nor are these forms of religion marked by rigidly drawn lines of affiliation; in brief; there are families, temples, and shrines, but no church. Even the ``community supporting the temple dedicated to a local god is shifting, depending on those who choose to offer incense or make other offerings there on a monthly basis. There are specialists involved in these examples of Chinese popular religion, but their sacerdotal jobs are usually not full- time and seldom involve the theorizing about a higher calling typical of organized religion. Rather, their forte is considered to be knowledge or abilities of a technical sort. Local temples are administered by a standing committee, but the chairmanship of the committee usually rotates among the heads of the dominant families in the particular locale.

Like other categories, ``popular religion in the sense of shared religion obscures as much as it clarifies. Chosen for its difference from the unspoken reality of the academic interpreter (religion in modern Europe and America), popular religion as a category functions more as a contrastive notion than as a constitutive one; it tells us what much of Chinese religion is not like, rather than spelling out a positive content. It is too broad a category to be of much help to detailed under standing--which indeed is why many scholars in the field avoid the term, preferring to deal with more discrete and meaningful units like family religion, mortuary ritual, seasonal festivals, divination, curing, and mythology. ``Popular religion in the sense of common religion also hides potentially significant variation: witness the number of times words like ``typical, ``standard, ``traditional, ``often, and ``usually recur in the preceding paragraphs, without specifying particular people, times, and places, or naming particular understandings of orthodoxy. In addition to being static and timeless, the category prejudices the case against seeing popular religion as a conflict-ridden attempt to impose one particular standard on contending groups. Several of the contributions to this volume, for instance, are works from non-Han cultures. Their inclusion suggests that we view China not as a unitary Han culture peppered with ``minorities, but as a complex region in which a diversity of cultures are interacting. To place all of them under the heading of ``popular religion is to obscure a fascinating conflict of cultures.

We may expect a similar mix of insight and erasure in the second sense of ``popular religion, which refers to the religion of the lower classes as opposed to that of the elite. The bifurcation of society into two tiers is hardly a new idea. It began with some of the earliest Chinese theorists of religion. Xunzi, for instance, discusses the emotional, social, and cosmic benefits of carrying out memorial rites. In his opinion, mortuary ritual allows people to balance sadness and longing and to express grief, and it restores the natural order to the world. Different social classes, writes Xunzi, interpret sacrifices differently: ``Among gentlemen [_junzi_], they are taken as the way of humans; among common people [_baixing_], they are taken as matters involving ghosts.<11> For Xunzi, ``gentlemen are those who have achieved nobility because of their virtue, not their birth; they consciously dedicate themselves to following and thinking about a course of action explicitly identified as moral. The common people, by contrast, are not so much amoral or immoral as they are unreflective. Without making a conscious decision, they believe that in the rites addressed to gods or the spirits of the dead, the objects of the sacrifice--the spirits themselves--actually exist. The true member of the upper class, however, adopts something like the attitude of the secular social theorist: bracketing the existence of spirits, what is important about death ritual is the effect it has on society. Both classes engage in the same activity, but they have radically different interpretations of it.

Dividing what is clearly too broad a category (Chinese religion or ritual) into two discrete classes (elite and folk) is not without advantages. It is a helpful pedagogical tool for throwing into question some of the egalitarian presuppositions frequently encountered in introductory courses on religion: that, for instance, everyone's religious options are or should be the same, or that other people's religious life can be understood (or tried out) without reference to social status. Treating Chinese religion as fundamentally affected by social position also helps scholars to focus on differences in styles of religious practice and interpretation. One way to formulate this view is to say that while all inhabitants of a certain community might take part in a religious procession, their style--both their pattern of practice and their understanding of their actions--will differ according to social position. Well-educated elites tend to view gods in abstract, impersonal terms and to demonstrate restrained respect, but the uneducated tend to view gods as concrete, personal beings before whom fear is appropriate.

In the social sciences and humanities in general there has been a clear move in the past forty years away from studies of the elite, and scholarship on Chinese religion is beginning to catch up with that trend. More and more studies focus on the religion of the lower classes and on the problems involved in studying the culture of the illiterati in a complex civilization. Many of the contributors to this anthology reflect a concern not only with the ``folk as opposed to the ``elite, but with how to integrate our knowledge of those two strata and how our understanding of Chinese religion, determined unreflectively for many years by accepting an elite viewpoint, has begun to change. In all of this, questions of social class (Who participates? Who believes?) and questions of audience (Who writes or performs? For what kind of people?) are paramount.

At the same time, treating ``popular religion as the religion of the folk can easily perpetuate confusion. Some modern Chinese intellectuals, for instance, are committed to an agenda of modernizing and reviving Chinese spiritual life in a way that both accords with Western secularism and does not reject all of traditional Chinese religion. The prominent twentieth-century Confucian and interpreter of Chinese culture Wing-tsit Chan, for instance, distinguishes between ``the level of the masses and ``the level of the enlightened. The masses worship idols, objects of nature, and nearly any deity, while the enlightened confine their wor ship to Heaven, ancestors, moral exemplars, and historical persons. The former believe in heavens and hells and indulge in astrology and dream interpretation, but the latter ``are seldom contaminated by these diseases.<12> For authors like Chan, both those who lived during the upheavals of the last century in China and those in Chinese diaspora communities, Chinese intellectuals still bear the responsibility to lead their civilization away from superstition and toward enlightenment. In that worldview there is no doubt where the religion of the masses belongs. From that position it can be a short step--one frequently taken by scholars of Chinese religion--to treating Chinese popular religion in a dismissive spirit. Modern anthologies of Chinese tradition can still be found that describe Chinese popular religion as ``grosser forms of superstition, capable only of ``facile syncretism and resulting in ``a rather shapeless tradition.

Kinship and Bureaucracy

It is often said that Chinese civilization has been fundamentally shaped by two enduring structures, the Chinese family system and the Chinese form of bureaucracy. Given the embeddedness of religion in Chinese social life, it would indeed be surprising if Chinese religion were devoid of such regulating concepts. The discussion below is not confined to delineating what might be considered the ``hard social structures of the family and the state, the effects of which might be seen in the ``softer realms of religion and values. The reach of kinship and bu reaucracy is too great, their reproduction and representation far richer than could be conveyed by treating them as simple, given realities. Instead we will explain them also as metaphors and strategies.

Early Christian missionaries to China were fascinated with the religious aspects of the Chinese kinship system, which they dubbed ``ancestor worship. Recently anthropologists have changed the wording to ``the cult of the dead because the concept of worship implies a supernatural or transcendent object of veneration, which the ancestors clearly are not. The newer term, however, is not much better, because ``the dead are hardly lifeless. As one modern observer remarks, the ancestral cult ``is not primarily a matter of belief. . . . The cult of ancestors is more nearly a matter of plain everyday behavior. . . . No question of belief ever arises. The ancestors . . . literally live among their descendants, not only biologically, but also socially and psychologically.<13> The significance of the ancestors is partly explained by the structure of the traditional Chinese family: in marriages women are sent to other surname groups (exogamy); newly married couples tend to live with the husband's family (virilocality); and descent--deciding to which family one ultimately belongs--is traced back in time through the husband's male ancestors (patrilineage). A family in the normative sense includes many generations, past, present, and future, all of whom trace their ancestry through their father (if male) or their husband's father (if female) to an originating male ancestor. For young men the ideal is to grow up ``under the ancestors' shadow (in Hsu's felicitous phrase), by bringing in a wife from another family, begetting sons and growing prosperous, showering honor on the ancestors through material success, cooperating with brothers in sharing family property, and receiving respect during life and veneration after death from succeeding generations. For young women the avowed goal is to marry into a prosperous family with a kind mother-in-law, give birth to sons who will perpetuate the family line, depend upon one's children for immediate emotional support, and reap the benefits of old age as the wife of the primary man of the household.

Early philosophers assigned a specific term to the value of upholding the ideal family: they called it _xiao_, usually translated as ``filial piety or ``filiality. The written character is composed of the graph for ``elder placed above the graph for ``son, an apt visual reminder of the interdependence of the generations and the subordination of sons. If the system works well, then the younger generations support the senior ones, and the ancestors bestow fortune, longevity, and the birth of sons upon the living. As each son fulfills his duty, he progresses up the family scale, eventually assuming his status as revered ancestor. The attitude toward the dead (or rather the significant and, it is hoped, benevolent dead--one's ancestors) is simply a continuation of one's attitude toward one's parents while they were living. In all cases, the theory goes, one treats them with respect and veneration by fulfilling their personal wishes and acting according to the dictates of ritual tradition.

Like any significant social category, kinship in China is not without tension and self-contradiction. One already alluded to is gender: personhood as a function of the family system is different for men and women. Sons are typically born into their lineage and hope to remain under the same roof from childhood into old age and ancestorhood. By contrast, daughters are brought up by a family that is not ultimately theirs; at marriage they move into a new home; as young brides without children they are not yet inalienable members of their husband's lineage; and even after they have children they may still have serious conflicts with the de facto head of the household, their husband's mother. Women may gain more security from their living children than from the prospect of being a venerated ancestor. In the afterlife, in fact, they are punished for having polluted the natural world with the blood of parturition; the same virtue that the kinship system requires of them as producers of sons it also defines as a sin. There is also in the ideal of filiality a thinly veiled pretense to universality and equal access that also serves to rationalize the _status inaequalis_. Lavish funerals and the withdrawal from employment by the chief mourner for three years following his parents' death are the ideal. In the Confucian tradition such examples of conspicuous expenditure are interpreted as expressions of the highest devotion, rather than as a waste of resources and blatant unproductivity in which only the leisure class is free to indulge. And the ideals of respect of younger generations for older ones and cooperation among brothers often conflict with reality.

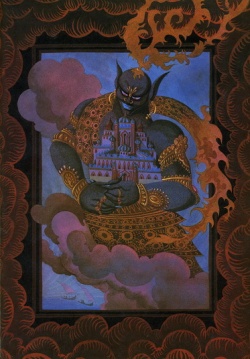

Many aspects of Chinese religion are informed by the metaphor of kinship. The kinship system is significant not only for the path of security it defines but also because of the religious discomfort attributed to all those who fall short of the ideal. It can be argued that the vagaries of life in any period of Chinese history provide as many counterexamples as fulfillments of the process of becoming an ancestor. Babies and children die young, before becoming accepted members of any family; men remain unmarried, without sons to carry on their name or memory; women are not successfully matched with a mate, thus lacking any mooring in the afterlife; individuals die in unsettling ways or come back from the dead as ghosts carrying grudges deemed fatal to the living. There are plenty of people, in other words, who are not caught by the safety net of the Chinese kinship system. They may be more prone than others to possession by spirits, or their anomalous position may not be manifest until after they die. In either case they are religiously significant because they abrogate an ideal of proper kinship relations.