The intermediate state after death

Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche: Bardo

ALL SENTIENT BEINGS ARE IN A SITUATION called bardo. Bardo means an intermediate state which is between two points of time. Right now we are in the intermediate state between our birth and our death called the bardo of this life. This bardo lasts from the moment we take birth until we enter the circumstances that will cause our passing away. Two other bardos are sometimes included within the bardo of this life. They are called the bardo of meditation and the bardo of dreaming. We need to train in the bardo of meditation during the daytime and the bardo of dreaming during the night. Now, to train in the bardo of meditation, we need to understand what is meant by buddha nature.

Buddha nature is present in everyone, without any exception. It is the very core of our being, the very nature of our mind. It is nature totally free from all faults and fully endowed with all perfect qualities. What we need to do now is simply to recognize our nature, and then sustain the recognition of that. There is no need to create or manufacture a buddha nature through meditation. It’s also essential to realize that every experience manifests and vanishes within the expanse of our buddha nature.

The bardo of meditation takes place during the period of time we are able to recognize our buddha nature, the dharmakaya nature of our mind. Involvement in conceptual thinking is not called meditation. Meditation in this context refers to the time when the thought has ceased and there is an absence of conceptual thinking. To repeat that period over and over again, from the cessation of thought to its re-occurrence, is called training in the bardo of meditation. Unless we recognize this nature, we will continue in samsaric existence, taking rebirth in one realm after the other. Sentient beings take birth from one place to the next in samsaric existence precisely because of not recognizing their nature. This lack of knowing their nature is called ignorance.

Essential meditation teachings are called pith instructions, and they are both profound and direct. To illustrate this point I will tell about pith instructions given by Paltrül Rinpoche. Once, Chokgyur Lingpa went to a tent camp in the province of Golok to meet Paltrül Rinpoche, and stayed with him a week. During that week Chokgyur Lingpa and his daughter received transmission for the Bodhicharya Avatara and essential meditation teachings.

One evening Paltrül Rinpoche taught the daughter of Chokgyur Lingpa, Könchok Paldrön, who was to become my grandmother. She remembered his words very clearly, and later repeated them to me. She imitated Paltrül Rinpoche’s thick Golok accent, and said, “Don’t entertain thoughts about what has passed, don’t anticipate or plan what will happen in the future. Leave your present wakefulness unaltered, utterly free and open. Aside from that, there is nothing else whatsoever to do!” What he meant was, don’t sit and think about what has happened in the past, and don’t speculate on what will appear in the future, or even a few moments from now. Leave your present wakefulness, which is the buddha nature of self-existing wakefulness, totally unmodified. Do not try to correct or alter anything. Leave it free, as it naturally is, free and wide-open like space. There is nothing more to do besides that. These are the vajra words of Paltrül Rinpoche, and they are truly meaningful.

Present ordinary mind is that quality or capacity that is conscious in everyone, from the Buddha Samantabhadra and Vajradhara all the way down to the tiniest insect. All sentient beings are aware or conscious. That which is aware or conscious is what we call mind, that which knows. It is conscious, yet it also is empty, not made out of anything whatsoever. These two qualities, being conscious and empty, are indivisible. The

essence is empty; the nature is cognizant; they are impossible to separate, just as wetness can’t be separated from water, nor heat from a flame. Once this nature has been recognized, training in the bardo of meditation can begin. At the moment of not recollecting anything from the past, not being involved in contemplating the future and not being preoccupied with something else in the present; let your present wakefulness gently recognize itself. When you allow this, there is an immediate and vividly awake moment. Do not try to modify or improve upon this moment of present wakefulness. Leave it open and free as it is.

As for the bardo of dreaming, dreams only occur after we have fallen asleep, don’t they? Without sleep, there are no dreams. What we experience while dreaming is experienced due to confusion. After we awaken, from where did the dream come? Where has the dream experience gone? We cannot find either of those places. It’s exactly the same with the delusory daytime experiences of all the six classes of beings. Examine where your dreams originate from, where they dwell, and where they disappear to. Understand that although the dream does not truly exist, we are still deluded by it. Now, consider the dream as an example for our being conditioned by ignorance. The buddhas and bodhisattvas are like people who have never fallen asleep and therefore are not dreaming, while sentient beings, due to their ignorance, have fallen asleep and are dreaming. Buddhas exist in the primordial state of enlightenment, a state that is completely undeluded. This state moreover is endowed with all qualities and free from all defects. Cut through your daytime confusion, and the double delusion of dreaming atop deluded samsaric existence ceases as well.

After the bardo of this life comes the bardo of dying. The bardo of dying begins the moment we catch an incurable disease that will cause our death, until the moment we draw our last breath. The period lasting from the inception of illness until our spirit leaves the body is called the bardo of dying.

It is said that the best possible achievement is to be liberated into the expanse of dharmakaya during the bardo of dying. If we have recognized our basic nature of self-existing wakefulness and grown accustomed to it through repeated training; a supreme opportunity arises at the moment just before physical death. If we are adept enough we can engage in dharmakaya phowa, the mingling of self-existing awareness, the dharmakaya nature of mind, with the openness of basic space. This is the highest kind of phowa: in it there is no ejector and no thing to eject. You remain in utterly pure samadhi; mind indivisible from basic space. Dharmakaya is like space in that it is all-pervading and impartial. When nondual awareness mingles with basic space, this all-pervasiveness and space are inseparable. The foundation for dharmakaya phowa is the realization of the self-existing wisdom that is present in each one of us. It is our awareness that needs to be recognized. Mingle awareness with the clear sky and rest in the phowa where nothing is moved, ejected or transferred. This liberation into primordial purity is the foremost type of phowa.

If you have not recognized nondual awareness, or have not trained sufficiently, and therefore can’t effect dharmakaya phowa, the bardo of dying will progress further. The ‘outer breath’ of perceptible inhalation and exhalation will cease, while the ‘inner breath’ of subtle energies still continues to circulate. Between the ceasing of the outer and inner breaths occur three experiences called appearance, increase and attainment. These take place when the white element from your father, situated at the top of the central channel at the crown your head, begins to move downwards, inducing an experience of whiteness that is likened to moonlight. Next the red element from your mother, situated below the navel, begins to move upwards to the heart center, generating an experience of redness that is like sunlight. The meeting of these two elements brings about an experience of blackness followed by unconsciousness.

Simultaneous with the unfolding of these three experiences, all the different ‘80 innate thought states’ arising from the three poisons of desire,

anger and delusion cease. There are 40 thought states that arise from desire, 33 thought states that arise from anger and seven thought states that arise from delusion. Every one of these ceases at the moment of blackness. It is like the earth and sky merging: everything suddenly grows dark. The conceptual frame of mind is temporarily suspended. If you are a practitioner who is familiar with the awakened state of nonconceptual awareness, you will not black out and fall unconscious at this point. Instead, you will recognize the unceasing and unobstructed state of rigpa. To reiterate, first there is the whiteness of appearance, second the redness of increase and finally the blackness of attainment. These three are followed by the state called the ground luminosity of full attainment, which is the dharmakaya itself. People who are unfamiliar with the awakened state of mind revealed by the cessation of conceptual thought will at this point revert into a state of oblivion — the pure and undiluted state of ignorance that is the very basis for further samsaric existence. For most beings, this oblivious state of ignorance lasts until the ‘sun rises on the third day’. However, an individual who has received instructions from a spiritual teacher and has been introduced to the true nature can recognize dharmakaya and attain enlightenment at this point, without falling into unconsciousness.

This recognition and awakening are often called the merging of the luminosity of ground and path, or the merging of the luminosity of mother and child. Through the power of genuine training in the bardo of meditation this recognition occurs as naturally and instinctively as a child jumping onto his mother’s lap: the mother and the child know one another, so there is no doubt, no hesitation. This recognition occurs instantaneously. A tantra declares: “In one moment, the difference is made. In one moment, complete enlightenment is attained.” If this happens, there is no reason to undergo any further bardo experiences. Liberation is attained right then.

For someone who fails to be liberated at the moment of death, according to the Liberation Through Hearing in the Bardo known among Tibetans as Bardo Tödröl, the ensuing bardo states are said to generally last 49 days, with a certain sequence of events occurring every seven days. This is true for the average person who has engaged in a mixture of good and evil deeds. For a person who has committed a great deal of evil during his lifetime, the bardo can be very short; he or she may plunge immediately into the lower realms. For very advanced practitioners the bardo is also very short, because there is immediate liberation. But for the ordinary person who is somewhere in between these two states, the intermediate state is said to last an average of 49 days.5

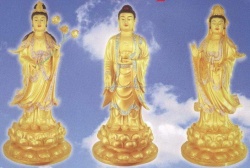

After the bardo of dying the bardo of dharmata begins. Ordinary people feel they have woken up after being in an unconscious state for three and a half days; to them it seems as though the sky unfolds again. Various dissolution stages occur during the bardo of dharmata: mind dissolving into space, space into luminosity, luminosity into unity, unity in wisdom and, finally, wisdom dissolving into spontaneous presence. Here, this unity refers to the form of the deities. First, colors, lights and sounds will occur. Only four colors appear at this time, and this is called the experience of the four wisdoms combined. The green light of all-accomplishing wisdom is missing at this point, because the path has not yet been perfected. ‘Luminosity dissolving into unity’ refers to the forms of the deities. Different deities begin to appear, first in their peaceful and then in their wrathful form. Some are as tiny as mustard seeds, while others are as big as Mount Sumeru. The most important thing at this point is to recognize that everything, whatever appears, is a manifestation of your nature. The deities are your own manifestations: they do not come from anywhere else. So, feel 100% confident that whatever is experienced is nothing other than yourself. Another way of explaining this is that whatever appears is emptiness, and that which experiences is also

emptiness. Emptiness cannot harm emptiness, so there is no point whatsoever in being afraid. With that kind of confidence, it is possible to attain liberation at the sambhogakaya level.

The light from the peaceful and wrathful deities is intense and overwhelming. If you have received instructions regarding this stage, you can recognize them with confidence as expressions of your own essential nature. Otherwise, pale, soft lights representing the six realms will appear in different colors. Those who are unfamiliar with such phenomena will be naturally attracted to those more comfortable types of light, and this attraction is what pulls the mind back into the six realms of existence. In this way the fourth bardo, the bardo of becoming, begins.

During the bardo of becoming, your power of perception is seven times clearer than during the normal waking state in this life. You will remember whatever you have done in the past and will be able to understand whatever is taking place. You will possess six recollections: the ability to remember the teacher, the teachings, the yidam deity for whom you have received empowerment, and so on. When remembering the teachings you received and practiced, it is most important to acknowledge that you have died and are in the bardo state. Next, try to remember that everything that takes place in the bardo is deluded experience. While various things are perceived, they lack any self-nature, unlike in our present experience. Now, if we put our hand into boiling water or into a flaming furnace it will burn. Likewise, we can be crushed by the weight of huge stones. But in the bardo, nothing that takes place is real. Everything is just an illusory experience — so how can it harm you? This is very important to keep in mind.

At this point in the bardo, the force of your intention is unobstructed. It is thus possible to take rebirth in one of the five natural nirmanakaya realms, the five pure lands of the nirmanakaya buddhas. The easiest place to be born is in Sukhavati, the Blissful Realm of Buddha Amitabha. Buddha Amitabha made thirteen eminent vows in the past, and due to the strength of these it is not necessary to have purified all disturbing emotions before being reborn in his pure realm. To enter the other buddhafields, total purification is necessary, but this is not true for Sukhavati. What is most important here is to be free from doubt. Engendering one-pointed determination like an eagle soaring through the sky, think without any hesitation, “I will now go directly to the pure land of Amitabha!” If you can hold to this single thought in the bardo of becoming, that alone is sufficient to go there. As long as you are not attached to anything, nothing can tie you down or prevent you from reaching Sukhavati. To be sure that you are free of attachments, before death, mentally offer everything you own to Buddha Amitabha. Make a mandala offering out of all your possessions and enjoyments, relatives and friends. Anything to which you remain attached, even something as small as a needle and thread; is enough to act as an anchor for your mind. When the body is left behind, only the consciousness continues on — all alone like a strand of hair plucked from a slab of butter. If the consciousness is not bound by attachment to anything in this world, then nothing can hold it back, though the existence of doubt can make some difference. A consciousness that harbors doubt about rebirth in the pure land of Amitabha can still be reborn there, but it will remain captive inside a closed lotus bud for 500 years, until it has purified the obscuration of doubt. If you can surrender all attachment to the things you have known in this life and one-pointedly make the resolve, “I will go straight to Amitabha’s pure land,” then it is 100% certain that you will arrive. There is no hesitation or question whatsoever about this.

In the bardo of becoming you will remember, “My stability in practice was not sufficient for me to be liberated into dharmakaya at the moment of passing away. It was also not quite sufficient to be liberated into sambhogakaya during the bardo of dharmata. So now here I am in the bardo of becoming.” Acknowledging this, make up your mind to be completely free of attachment to anything. Otherwise, even the smallest attachment to relatives or possessions will obsess and worry your spirit,

like a dog chasing a scrap of meat. Only such attachments can really tie your consciousness back to this world.

If you do have to be reborn in this world, you will continue through the bardo of becoming while seeking a new rebirth. When meeting the parents who will give birth to you, imagine them as the yidam deity with consort. Let your mind enter the womb in the form of the syllable HUNG, and make the resolve to become a pure Dharma practitioner.

The Vajrayana teachings provide many opportunities, many chances on different levels. If we miss one opportunity, we get another chance, and if we miss that there is still a chance to try again. As long as your samayas are unbroken, there are many precious teachings in Vajrayana that will help you cross the bardos.

When you are fatally sick or when you face death, make up your mind to combine the practice of recognizing mind essence with the resolve to go straight to the pure land of Sukhavati. As the great master Karma Chagmey said, “May I soar like a vulture in the sky directly to Sukhavati, without looking back for a single moment!” Don’t look back! Remain totally unattached to anything in this world. Don’t have any doubt: then there is no question that you will go straight there.

Always remember to begin with taking refuge and forming the bodhichitta resolve to benefit all beings. For the main part of practice, imagine yourself as the yidam deity. This is called the development stage. Gently look into, “Who is it that visualizes? What is it that imagines all this?” Not finding anything which visualizes or imagines is called the completion stage. At the very same moment of looking into the thinker, the fact that there is no thing to see is immediately seen. Anyone can see that, if they know how to look. In the very first instant there is an absence of thought. This state is not like a black-out, in that you are not unconscious, but vividly awake. Yet this wakefulness doesn’t form thoughts about anything. It’s like space; not the night sky, covered by darkness, but like the sky lit by sunlight, where the sunlight and space are indivisible. That is the naked ordinary mind present in everyone. It’s

naked because at that moment there is no conceptualizing, no thought activity. Ordinarily, every moment of consciousness is occupied with conceptualizing and creating something. Therefore, leave your present wakefulness totally unfabricated.

Remember always to conclude your practice by dedicating the merit and making pure aspirations. The pain may be very strong when we are seriously ill; we might be in agony and feel miserable. Give up the thought, “I’m suffering! How terrible it is for me!” Instead, think, “May I take away all the pain and sickness of all sentient beings, and may their stream of negative karmic ripening be interrupted! May it all be taken upon myself! May I take upon myself all the sickness, difficulties and obstacles which the great upholders of the Buddhadharma experience. May their hindrances ripen upon me so that they all are free from any difficulties whatsoever!” Such an attitude accumulates an immense amount of merit and purifies immeasurable obscurations. It is difficult to find anything that can create more merit than keeping this perspective. It is much, much better than lying there moaning, “Why should this happen to me! Why do I have to suffer?” That kind of self-pity is not of much use. The wishes we make when we are close to drawing our last breath are incredibly powerful. It is said that the resolve the mind forms at the verge of death will definitely be fulfilled, whether it is pure or evil. Some people die with the thought, “So and so did that to me! May I take revenge!” Through the immense strength the mind displays during the last moments before expiring, that person’s mind can be reborn as a powerful evil spirit with the ability to harm others. On the other hand, if we make pure wishes and aspirations, there is no question that they will be fulfilled. With the finality of our human life acutely on our minds, the wishes we make and resolves we form are immensely powerful. This is very important to remember.

At the moment of death, ‘time does not change, experiences change’. Time here means that there is no real death that occurs, because our innate nature is beyond time. It is only our experiences that change. All these experiences should be regarded as nothing but a paper tiger. When we meet a real tiger, we will feel frightened, but if we see that it is merely an imitation — a paper tiger — we are not frightened at all. We have no fear that the paper tiger will eat us. In the same way, all the different experiences that occur after death all seem real, yet they’re not. In the bardo, flames cannot burn us, weapons cannot cut us; everything is illusory and insubstantial. It is emptiness.

At Tulku Chökyi Nyima Rinpoche’s monastery, called Bong Gompa, north of Central Tibet, the bursar was about to pass away. My uncle, Tersey Tulku was present. While the bursar was dying, he never stopped talking. He said, “Well, well, now this element is dissolving, now that element is dissolving, now consciousness is dissolving into space. Now space is split open and all the different manifestations are appearing. The vajra chains are fluttering around like crystal garlands and fresh flowers. Dharmata is truly amazing!” He was laughing, and then he died. Of course, he was someone who was quite stable in awareness. The experiences that will appear at death and after are inconceivable, and cannot exactly be described beforehand. One thing is certain, however: whatever is experienced is a ‘mere appearance without any selfnature,’ merely felt to be, yet insubstantial. Everything is the play of emptiness. Whatever is experienced is nothing other than a manifestation of your innate nature — visible, but with no concrete substance. Not recognizing that whatever appears in the bardo is your nature; you can be terrified by the sounds, frightened by the rays and afraid of the colors. These sounds, colors and lights are the natural manifestation of buddha nature. They are, in fact, the Body, Speech and Mind of the enlightened state: the colors are the Body, the sounds are the Speech, and the light rays are the manifestation of Mind. They appear to everyone, without exception, because everyone has buddha nature.

Although these experiences appear to everyone, they can differ in the length of time they are experienced. This probably corresponds to the degree of stability in mind essence. Other than this difference in duration,

the experiences are the same for everyone. The most important thing to remember is not to feel sad or depressed about anything — there is no point in that. Instead, have the attitude of a traveler who is returning home while joyfully carrying the burden of the suffering of all sentient beings.

*Intermediate State between Existences* From the Theravadin Perspective

Basically, Ajahn Brahm (and the forest monks of Ajahn Chah) believe there is an antarabhava, partly from the numerous accounts in the Suttas, and according to Ajahn his personal experiences dealing with the dying in Thailand (I have not inquired further on this). Hoping he has written on this and will be published.

In contrast to the orthodox stand, there is significant Pali canonical evidence strongly suggestive of an intermediate state between one existence and another, a view supported by Theravada fundamentalists. Various suttas from the Nikayas clearly talk about a state of existence before actual rebirth as a another sentient being. Let me quote some examples from them.

In Mahatanhasankhaya Sutta (MN 3Cool the Buddha states that for conception to occur, one of the conditions is that the being to be reborn (gandhabba) has to be present at the moment of union between the father and mother. Here, it is implicitly stated that there is an intermediate state of existence between death in the previous existence and rebirth in the next.

There are various references to the rebirths of bodhisattas as well as other beings, which also imply as much. According to Sampasadaniya Sutta (DN 2Cool and Sangiti Sutta (DN 33), some beings "enter the mother's womb unknowing, stay there unknowing and leave it unknowing", while others "enter the mother's womb knowing, stay there knowing, and leave it unknowing". One who "enters the mother's womb knowing, stays there knowing and leaves it knowing is, according to the commentary, a bodhisatta in its last rebirth. This is confirmed by several suttas that describe the bodhisatta's moment of entry into the mother's womb as "being mindful and fully aware. Mahapadana Sutta (DN 14); Acchariya-abbhuta Sutta (MN 123); Pathama-tathagata-acchariya Sutta (AN 4: 27); Bhumicala Sutta (AN 8:70).

There are references to a fivefold typology of non-returners, one of which is called antaraparinibbayi (attainer of Nibbana in the interval�Wink, in the Samyutta Nikaya (SN 48:15, 24, 66, 51:26, 54:5, 55:25); Purisagati Sutta (AN 7:55) and Samyojana Sutta (AN 4:131). Ven Bhikkhu Bodhi, in his "The Connected Discourses of the Buddha: a new translation of the Samyutta Nikaya", Volume II (Note 65, Pp 1902-1903), argues (with support from Samyojana Sutta) that the antaraparinibbayi is "one who has abandoned the fetter of rebirth (upapattisamyojana) without yet having abandoned the fetter of existence (bhavasamyojana)."

Orthodox Theravadins argue against this interpretation of the antaraparinibbayi because in the Kathavatthu (e.g. Kv 366), an Abhidhamma text regarded by them as canonical, the idea of antarabhava (intermediate life) was strongly refuted.

However, there is further evidence to consider. In Metta Sutta (Khp 9, Sn 1:Cool there is reference to bhuta (those who have been born) and sambhavesi (those seeking birth). Several suttas Channovada Sutta (MN 144); Channa Sutta (SN 4:35:87); Catuttha-nibbana-patisamyutta Sutta (Ud 74)] mention the states of "here or beyond or between the two". Kutuhala Sutta (SN 4:44:9) also tells of "a being [that] has laid down his body but has not yet been reborn in another body".

All the above references from the suttas implying an intermediate state of existence should provide sufficient food for thought by Theravadins and ample reason to keep an open mind regarding the mystery of dying and rebirth.

Although fundamentalist Theravadins may subscribe to a belief of an intermediate afterlife, it does not necessarily mean that they accept all of the bardo (gap in between or intermediate state) teachings postulated by the Vajrayana tradition.