Tibet: Mystic Trivia

Genii loci: The Tibetans believed in these - spirits that haunted the mountain peaks; the higher the mountain, the more baleful the spirits. (Altitude sickness causes delusions; hence the belief in genii loci and the well-documented European legends about mountain passes being haunted by dragons, ogres, trolls and supernatural creatures. Both cultures had a dread of heights, which the Europeans lost earlier.)

Nekyia: a descent into the Underworld.

Mana walls: long snaking freestone walls which lay crisscross over the Tibetan landscape - each stone of every such wall was inscribed with a prayer.

Ningma-ningma: 'the most ancient of the ancients' refers to the Red Cap lama sect, which differs from the Yellow Cap sect in that Red Cap lamas are the ones who learn magic, mystic arts, etc.

Immured anchorites: in 1904, a The Times special correspondent named Perceval Landon accompanied a British expedition to Lhasa. He visited the Nyen-de-kyi-buk monastery, which was famous for its immured monks, and the abbot allowed him to see one. Each of these monks had taken a vow to live in darkness, walled up in the tomb of a cell just large enough for a single man to sit inside in a position of meditation; some for six months, some for three years and ninety-three days, and many of the rest of their lives. In a small courtyard, Landon watched the abbot administer three sharp taps to a stone slab covering the entrance of one of these cells. He wrote, "It was the most uncanny thing I saw in all Tibet. What on earth was going to appear when that stone slab, which even then was beginning to quiver, was pushed aside, the wildest conjecture could not suggest." At first the stone seemed stuck, "then very slowly and uncertainly it was pushed back and a black chasm revealed. There was a pause of thirty seconds; during which imagination ran riot, but I do not think that any other thing could have been as intensely pathetic as that which we actually saw. A hand, muffled in a tightly-wound piece of dirty cloth, for all the world like the stump of an arm, was painfully thrust up, and very weakly it felt along the slab. After a fruitless fumbling the hand slowly quivered back again into the darkness. A few moments later there was again one ineffectual effort, and then the stone slab moved noiselessly again across the opening." Normally the monks signaled the anchorite once a day, when they left his meal of unleavened bread and water. Landon was bitterly regretful that his whim had disturbed the recluse's routine and forced him to the dreadful effort of heaving aside his slab for nothing. Even back in England he was forced to reflect upon the abbot, with whom he had taken tea: ". . . a picture of the same hand that one shook so warmly as one left the monastery, now weakly fumbling with swathed fingers for food along the slab of the prison in which the abbot now is sealed up for life: for he was going into the darkness very soon."

Lung-gom-pa: legendary lamas who by means of psychic training could rush nonstop across vast distances of rugged landscape, running without end. Description of meeting a lung-gom-pa (by the French mystic-scholar Alexandra David-Neel who, disguised as a beggar woman, gained rare insight into common Tibetan life) in a wilderness where, for ten days, no fellow human being had been sighted: "By that time he had nearly reached up; I could clearly see his perfectly calm impassive face and wide-open eyes with their gaze fixed on some invisible far-distant object situated somewhere high up in space. The man did not run. He seemed to lift himself from the ground, proceeding by leaps. It looked as if he had been endowed with the elasticity of a ball and rebounded each time his feet touched the ground. His steps had the regularity of a pendulum. He wore the usual monastic robe and toga, both rather ragged. His left hand gripped a fold of the toga and was half hidden under the cloth. The right held a phurba (magic dagger). His right arm moved slightly at each step as if leaning on a stick, just as though the phurba, whose pointed extremity was far above the ground, had touched it and were actually a support. My servants dismounted and bowed their heads to the ground as the lama passed before us, but he went his way apparently unaware of our presence."

Wild men of the Tibetan steppes: it was a common Tibetan folktale that hairy wild men lived up in the higher peaks, among the eternal snows - along with mythical white lions whose roars boom out during great storms. The supposed tracks of these supposed wild men were apparently those of "the great yellow snow bear". (This from an account of 1889.) A Tibetan lama told a Westerner of meeting hairy savages - speechless and naked creatures more like animals than men, with long tangled locks falling about them like cloaks. Mongolians called these creatures geresun bamburshe, "wild men"; Prejevalsky in 1871 reported the same creatures, calling them kung guressu or "man beast". British explorers were convinced these accounts stemmed from bear worship in the folk history of Central Asia; the yeti were mountain bears.

This is the same Prejevalsky who discovered Prejevalsky's Horse, and he discovered that in 1879 during a Tibetan expedition, in the remoteness of Mongolian Central Asia. He was looking for one of the wild strains from which modern horses are descended - one of the famous ponies used by Genghis Khan and the Mongol hordes. The Mongols obtained their mounts by domesticating the descendants of these wild ponies. One traveler, Bonvalot, reported that his small Tibetan horses were carnivorous and fed upon raw flesh.

Aborigines called Lepchas lived in the Himalayan forests; Europeans called them the lotos-eaters, the primeval Arcadians, but during the nineteenth century (?) they were already going extinct . . . There was another race called the Baltis which was, like the Lepchas, sure to soon vanish - superseded by the more energetic Nepalese and the sturdier Tibetans.

Sword spiraling: Tibetan mediums, in a state of trance, would bend long swords into spirals; friends of Harrer's possessed such swords, which they laid in state before their house-altars.

Thumo reskiang: lamaic art of self-heating. David-Neel studied this art. She saw hermits who sat meditating outside, naked upon snowbanks night after night, with blizzards whirling around them; she saw students of the discipline pass tests by drying on their bodies icy sheets fresh-dipped from Himalayan lakes in midwinter. P. 133, she meditates in the thumo rite, not only to warm herself but to dry flint and tinder so she can light a fire. Putting them under her dress, she sits and envisions flames rising, crackling around her, until it seems she can see them and she felt deliciously warm. When something made her start awake, she seemed to see the flames die down as if entering the ground, and opening her eyes she found her body burning, her face cherry red and her eyes bright, and the tinder and flint were dry and hot.

Tibetan demons: Palden Dorjee Lhamo, who rides a wild horse on a saddle made from a bloody human skin. The Angry Ones, who eat the flesh of men, whose delicacy is fresh brains served up in shattered skulls. The Frightful Ones, companions of King Death, who are crowned with bones and who dance upon corpses.

Poison stories of Tibet: "There is also in Thibet a curious class, including persons of both sexes, but especially women, who are reputed to be the hereditary keepers of "poison." What poison? Nobody knows. No one has ever seen a trace of it, but this very mystery adds to the terror it inspires. When the fatal time arrives, the one who is to administer it cannot escape the obligation. In default of a passerby who may afford him an opportunity, he must pour it out for one of his friends or relatives. One hears whispers of mothers who have poisoned their only sons, of husbands who have been obliged to hand the fatal cup to a dearly loved bride the day of their marriage; and if there is no one within reach, the "keeper" must drink the deadly poison himself.

"I have seen a man who was said to be the hero of a strange poison story. He was travelling, and on his way through a village he entered a farm to obtain refreshment. The mistress of the house prepared him some beer by pouring hot water upon fermented grain placed in a wooden pot, according to the custom of the Himalayan Thibetans. She then went upstairs. When left alone the traveller remarked, with some astonishment, that the beer placed before him, in the wooden vessel, was boiling in great bubbles. Near by water was also boiling in a cauldron, but in a natural way. The man took a large ladle of this, and emptied it over the suspicious-looking beer. At that moment he heard a fall on the floor above his head. The woman who had served him had fallen down dead."

Tibetans also believed there were special, magic wooden bowls which are sensitive to the presence of any poison poured into them. Such bowls are sold for very high prices. From David-Neel's account.

Dorjee Phagmo, the diamond or most excellent sow: the female Incarnation of a Buddhist Tantric deity from India. She is a high lama and her residence is the Sanding monastery, in the town of Gyantze in south Tibet, which was in the first part of the twentieth century a British outpost. The monastery stands (?) in the strangely shaped Yamdok Lake, upon a peninsula on the lake which boasts a small separate lake of its own. The previous Dorjee Phagmos have been able to take on the form of a sow from time to time.

'Dorje Phangmo' is also the consort of the demon Demchog, with whom she is always depicted locked in sexual congress; she is red in color, and also identified with Durga (ie Devi/Gauri/Parvati/Durga/Kali, consort of Shiva) and also Tseringma and Vajra-Varahi. Demchog is the four-faced Tibetan deity representing Supreme Bliss, resident on Kang Rinpoche mountain.

On the eastern course of the river Tsangpo, the river runs serenely through a wide, lush valley of birch and oak forests and then between narrowing cliffs toward two rounded mountains - which the river passes right between, thereupon turning north into a deep gorge and becoming a monster of wild, white waters. The two mountains, now known as Namche Barwa and Gyala Peri, were once said to be the two magnificent breasts of the goddess Dorje Phangmo.

Ghosts in the Lop Nor, from Marco Polo's description of the Desert of Lop: "The length of this desert is so great that 'tis said it would take a year and more to ride from one end of it to the other. And here, where its breadth is least, it takes a month to cross it. 'Tis all composed of hills and valleys of sand, and not a thing to eat is to be found on it. But after riding for a day and a night you find fresh water, enough mayhap for some fifty or a hundred persons with their beasts, but not for more ....

"Beasts there are none; for there is nought for them to eat. But there is a marvellous thing related of this Desert, which is when travellers are on the move by night, and one of them chances to lag behind or fall asleep or the lake, when he tries to gain his company again he will hear spirits talking,a nd will suppose them to be his comrades. Sometimes the spirits will call him by name; and thus shall a traveller oft-times be led astray so that he never finds his party. And in this way many have perished. Sometimes a stray traveller will hear as it were the tramp and hum of a great cavalcade of people away from the real line of road, and taking this to be their own company they will follow the sound; and when day breaks they find that a cheat has been put on them and that they are in an ill plight. Even in the day time one hears those spirits talking. And sometimes you shall hear the sound of a variety of musical instruments, and still more commonly the sound of drums. Hence in making this journey 'tis customary for travellers to keep close together. All the animals too have bells at their necks, so that they cannot easily get astray. And at sleeping time a signal is put to show the direction of the next march. So thus it is that the desert is crossed."

Megaliths and stone carvings: many images of the Bodhisattva Maitreya along caravan routes of central Asia. One: B M represented standing, attired in the lavish costume of a rajakumara or royal prince; right hand upraised holding rosary; left holding vase; diadem upon head.

Stone carvings of ibex, archers, and swastikas widespread throughout Ladak and the neighboring mountain countries - attributed to Bon religion. "The ibex is very popular in the ancient fire cult of the Mongols." The svastika or gYung-drung is the symbol of the Bon religion. Huge boulders decorated with figures of ibex, bowmen, circles of dancing men; such paintings are common throughout Tibet, and some are contemporary and some are ancient.

Stucco images on Leh stupas: winged horses, lions, peacocks, swans. Curious group of monuments in nearby town: Maltese crosses with inscriptions; writing was found to be Sogdian (!) Possibly made by Nestorian Christians during 8-10th century AD when Nestorian colonies were common throughout central Asia.

Barrows seen by expedition in Mongolia, eighteen large and six smaller ones. They had stone cairns on their tops and were surrounded by concentric rings of stone slabs. (From Trails to Ancient Asia.)

Ancient Leh graves excavated by missionaries, found to have subterranean crypts, handmade pottery, beads, small bronze objects, etc; "Some of the pots were filled with human bones. This fact seems to indicate that the people who built these graves were in the habit of cutting up the body and depositing the bones and flesh in jars." Graves are believed to be Dard, but this is not proven. The locals call them nomad graves.

At Do-ring, thirty miles south of the great salt lake of Pang-gong tsho-cha, are megalithic alignments - eighteen rows of erect stone slabs, each running west to east, with at its western end a cromlech or stone circle made from several menhirs standing in a circle. (Stone alignments at Carnac in Brittany are arranged exactly like this - east-west lines with circles at the western ends.) At the eastern end of the alignment is an arrow of stone slabs, pointing toward the alignment. The arrow is also a sign of King Kesar. Butter libations were seen in the cromlechs. The great pilgrim route to Mount Kailasa runs south of the Great Lakes and also runs to the sacred places along the Nepalese border; the company is traveling through the midst of the Lakes, just north of Lhasa. Further along are another group of megaliths - three menhirs with stone slabs in a square around them, and also several graves, enclosed by stones arranged in a square; each grave runs east-west, with a boulder at the eastern end. Nearby, bronze arrowheads litter the ground. (From Trails to Inmost Asia.)

Macabre trivia: caravan routes all over the high country are marked by the abandoned carcasses of fallen animals, sometimes dozens of them. Ravens haunt the roads, feeding on the dead beasts; when a dying animal is left behind by its drivers, the ravens hover round it, pluck out its eyes and begin to feast on its entrails before it is even dead. Piles of merchandise are left carefully marked with the names of the owners, to be picked up on the way back; the mark of a caravan whose animals have mostly perished; no one will disturb these goods, the owner will collect them later. Later in the lowlands, they found the caravan routes blocked horribly by the huge carcasses of camels with swollen, bloated bellies; the Turkestani drivers customarily slit the throats of dying animals, putting them out of their misery.

"The carcasses of animals became more and more numerous. Some of them had probably died in terrible agony. The dry atmosphere had mummified them in strange attitudes, as though galloping, their heads thrown backward. Probably some caravaneers had set up the dead animals in standing posture and there was something strangely uncanny in these galloping, dead horses."

A shrine in the desert houses sacred doves; travelers buy grain to feed them. A king of Khotan built a temple dedicated to sacred rats, celebrating a victory over the Hiung-nu (?) when the enemy's ammunition was miraculously destroyed overnight by gnawing rats.

City of Urga (from Mongol orgo, ie princely camp, palace) - capital of Mongolia. Urga is the European name prior to 1924, when the Ikhe-Khuruldan or Great National Assembly of Mongolia changed the city's name to Ulan Bator Khoto, City of the Red Warrior. Native Mongols however always call it Ikhe-kuren or Ikhe-kura, the Great Monastery; in everyday language, they say Kuren, or perhaps the Sino-Mongolian name Da-kura (Ta-kura, Chinese transcription Ta k'u-lun). Many temples with glittering roofs. Miserable hovels also. Urga houses are surrounded by grey, weathered, high, wooden palisades with red-painted gates, with small wooden plates on which the house numbers are written. Inside each palisade is a large courtyard with a small one-storied house; a Mongol family uses their house only during the summer, and pitches their felt tent or tents in the courtyard. They prefer to live in the warm felt tent during the wintertime.

Huge packs of dogs infest Urga, sometimes attacking people. Dead bodies, animals and garbage are left out for the dogs to devour. Bodies are dumped in a valley north of the city, and the scavenging dogs sometimes drag back human skulls, bones with hair attached, etc, and leave them lying around. There is a cemetery where poor Chinese leave the dead in huge wooden coffins which rest on the ground, and as the dogs cannot break into these coffins the stench of the area is indescribable . . . Sometimes the coffins rot and the dogs scrape their way in and mutilate the hands and heads of the dead. Wealthy Chinese always send their dead home to China, and it is a commonplace thing along the trade routes to encounter a camel carrying one of these huge wooden coffins on its back.

Nomad Mongols throw the corpses of their children onto the trade routes, so that travelers may pray for their souls as they pass.

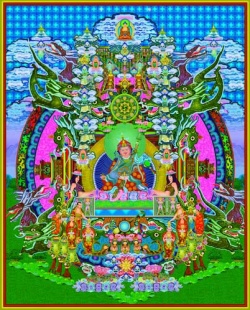

Kalacakra doctrine of knowledge. The mandala is its holy sphere of influence. It is a mystic sect or discipline derived from Mongolian astrology, prevalent in Mongolia; its center is the Tashilhumpo Monastery (ie the Tashi Lama's temple). In the future, the Tashi Lama will be reborn as Rigden Jye-po, the future ruler of Shambhala, whose destiny it is to conquer the followers of evil and rule the world in the name of Maitreya, the Future Buddha. This doctrine of Shambhala is the hidden faith of Tibet and Mongolia, and His Holiness the Tashi Lama is its chief expounder. Shambhala (a mountain range in NE Tibet) is considered to be the abode of hidden Buddhist learning, the secret heart of the coming kalpa or cosmic age, and it is from Shambhala that the final Holy War will sweep to win the world for Buddhism . . .

Black Hat dance performed during New Year ceremonies. Lamas perform it at the monasteries, dressed in black coats with green embroidered silk sleeves, over which are worn ru-rgyan or bone ornaments - and peculiar black hats, which give the dance their name. The tale goes that in the ninth century AD the king of Tibet, Lang-darma was a faithful follower of the Bon faith and suppressed Buddhism every way he could, closing lamaseries and massacring monks. A famous Buddhist ascetic called Pal-dorje decided to assassinate him. Accordingly, he rode into Lhasa mounted on a shaggy black pony (it was actually pure white, but he had painted it from nose to tail) and garbed in the manner of a Bon magician, with a bow and arrow concealed in his long sleeves. So attired, he was admitted into the presence of the king, where he began to dance a strange dance. Mesmerized, the wicked king drew near, staring at the dancing magician; whereupon Pal-dorje shot him with a poison arrow. The lama left his dying victim, fled toward his horse and vanished from the city - crossing a river upon his way, so that the coal with which his pony was painted washed away. Thus the warriors of the city, rushing out in pursuit of a Bon magician on a black horse, found only a poor Buddhist lama riding upon a white pony. So was Buddhism avenged, and so it is danced every New Year throughout Mongolia and Tibet.

Kanjur and Tanjur: collections of Buddhist holy writings. There are Kanjur manuscripts written in gold; they are rare and expensive, possessed only by the richest and oldest of families and a few lucky monasteries. The best have wooden covers carved with the figures of Buddhas and other religious motifs; the pages are made of several pieces of paper pasted together and painted black or very dark blue. The letters are of thick gold and thieves often steal pages or even whole books to scratch off the gold. So far as the author knows, there are few gold-letter Kanjurs outside Tibet, and no gold-letter Tanjurs in Tibet or anywhere else.

Earth poison: sa-du, sa-gdug; Tibetans and Mongols believe that the Khashgar pass (?) was evil ground with earth poison, bad for men and animals, and the only way to be sure of getting safely across was to chew garlic or else smoke strong Chinese tobacco continuously.

Thang La pass (reentering Tibet from the Tsaidam marshland) is said to be the abode of thirty-three gods or heavenly deities. Caravaneers believe that when an undesirable person enters Tibet, an scornful wind blows over the pass and the rejected traveler freezes then and there.

The Bons: followers of the faith which was supplanted in Tibet by Buddhism. David-Neel believes their faith may have been like that of shamanism in Siberia, but no written scriptures survive (that she saw; other travelers have seen and read Bon texts) and the present practice of Bon is like lamaism. The Bons themselves say they possess secret books of great antiquity, written before Buddhism entered their land; but no one has ever seen such books. Bon pilgrimage: to genuflect, always keeping the sacred edifice on the left, round the Kongbu Bon ri (ie Kongbu Bon hill) somewhere upstream on the Giamda river (?). (Lamaists when genuflecting round, say, the walls of Lhasa, keep the sacred edifice upon the right.)

There are two Bon sects, both resembling Red Cap lamaism but with the addition of animal sacrifice. The White Bons are lamaists with a dash of the old religious practices. The Black Bons "are more original and nearer the primitive shamanism." Also when lamaists will recite Aum Mani Padme Hum, the Bons will chant Aum Matriye salendu - which some travelers have understood to mean Matri Matris da dzu.

The Bon religion: Bon-po text: Ye-shes ni-ma lha'i rgyud or "Tantras of the Gods of the Sun of Wisdom" Ancient Bon religion marked by shamanistic and necromantic rituals, sacrifices (formerly of men, now of sheep, goats, clay images). There are gods of heaven and earth, of sun and moon, of stars and of the four quarters. Old Bon holy places: stone altars, menhirs, cromlechs. Alignments of stone slabs. Megalithic monuments found all the way along the old pilgrim road to Mount Kailasa are probably Bon holy shrines.

Bon gods: Bon-sku Kun-tu bsang-po is supreme, he is the All-good or Father Heaven. With him goes Mother Earth, Ma-btsun-pa. The Garuda god, Cha-khyung or Bya-khyung whose cult may be associated with the sacred eagle or griffon art in Asian nomad archeology. The Gods of the White Quarter are benevolent, the Gods of the Dark Quarter are malignant. All these together are designated by the title Gods of the Svastika. The prophet of the Bon was the great teacher, Shen-rap.

Lha: divine beings, countryside gods. Every region has its own lha.

Yul-lha: countryside god, spirit.

Lha-tho: Bon stone altar.

'Dre, dud, tong-dre: countryside demon. Along with its lha, every place has a 'dre. They will drive away horses at night, and generally cause mischief.

Kesar, the legendary Bon king, is like King Arthur. He is a Bon hero; with seven teachers or uncles he went to war; his wife was 'Bru-gu-ma. There is a large myth cycle concerning him, with songs which Bon believers sing in defiance of Lhasa.

Bon texts: often with titles of each text written in two languages, both probably artificial - the writer calls them unintelligible. They are the Shang-shung ska or "language of Shang-shung" and the gYung-drung lha' i skad or "language of the Swastika gods." The Tibetan language is called the language of men or gang-zag mi-wo'i skad, or in short form mi-wo'i skad. Texts are written in gold and silver on thick black paper, or else in black or red ink on plain pages with the title pages black with gold writing.

Lamaist Mongols call the Bon-po faith Khara-nom or "the Black Faith".

Aquatic cows, lake monsters: At Nya-shing Lake in the Great Lake country of Tibet, something called 'aquatic cows' lived in the waters. The lake is a salt one, and salt encrusts its banks with white. The aquatic cows could sometimes be seen at sunset, so the locals said, and the air resounded with their lowing. Sandy plains surround the lake; the whole of Nya-shing tsho is three days march across, that is fifty miles.

At Nam-ru lake, four days from Nya-shing tsho, are more aquatic cows; the lake is sometimes called Dung-tsho, because of the lowing of these aquatic cows.

The explorer Hearsey in 1812 saw a monster in Lake Manasarovar and wrote in his journal: "On returning before sunset I saw an enormous large Animal or Fish take a porpoise. He kept a considerable time upon the Surface, was of a brown colour and had apparently Hairs; I at first mistook it for a dead Chowhur until I saw it in motion when it disappeared." (A chowhur is a yak.)

Milarepa legends: at Everest, the "Lady of the Great Snow" Milarepa fought against the Bon teacher Naro (Naropi, Naro-Bonchung) - as in the Kailas legend, the sorcerer challenged the sage to fly up the mountain, and Milarepi simply appeared meditating at the top; Naro, blinded by the sparkling of this vision, fell into a deep precipice and in his downward tumble traced the sign of his defeat. There is a whole cycle of tales in which Milarepa engages in debate with Naropi.

In the present day, recluses can still be found who belong to the secret brotherhood of Milarepa's followers, called Brothers and Friends of the Hidden. Milarepa was a Red-cap monk, a teacher of tantric magic, and his cult is that which practices the hidden science of Inner Fire, lung-tum-mo or lung gtum-mo. His followers wear white robes (made dirty grey with usage) and their hair is pulled up and bound with a string at the crowns of their heads; they carry big damarus (magic drums) and tridents, with kang-lings or trumpets made of human bone fastened to their belts.

To become an adept of the Inner Fire, a lama must find a teacher - otherwise the attempt would be too perilous and would certainly drive him mad - and then eventually he will attain the stage of tum-mo in which he may even melt the snow around him for considerable distances. Magical manuals teaching tum-mo are written in mantra language "a highly technical form of literary Tibetan, using special expressions." There is a tale of a monk who practiced concentration leading toward tum-mo for fourteen years but was distracted at the last moment by an innocent traveler who approached and asked for directions; the lama experienced such a terrific shock at the interruption of his meditation that he went insane on the spot.