Tibetan Buddhism and Environmental Protection in China by Joshua Esler

Tibetan Buddhism and Environmental Protection in China

Joshua Esler, University of Western Australia

Abstract

This paper examines the recent convergence of Tibetan Buddhism and the environmental protection movement, particularly in China as an increasing number of Han Chinese are adopting Tibetan Buddhism.

Tibetan Buddhism has been ‘superscribed’ with many new layers of meaning as it has spread throughout Greater China (by Greater China I am specifically referring to mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan). These layers include traditional Chinese ideas and beliefs, as well as various discourses of modernity such as Chinese Marxism (in mainland China), modern Protestantism (in Hong Kong), and Humanistic Buddhism (in Taiwan). [1] Since the mid-1980’s Tibetan Buddhism in exile has also been layered with an ‘environmental superscription’. Following the visits of Tibetan Government in Exile delegations to Tibet from 1979 to 1985, and collaboration between the Dalai Lama and other Tibetans in exile with WWF and other environmental NGOs, the image of Tibetan Buddhism as ‘green’ has become more solidified. The fact-finding reports carried out by the aforementioned delegations from Dharamsala to Tibet, and ongoing reports of ecological destruction caused by Chinese occupation, has fuelled the West’s imagination of Tibetans and their religion as being environmentally friendly. Among many recent propagators of this ‘green Tibetan’ image is the 17th Karmapa in exile, who has instigated many noteworthy initiatives such as organising conferences on the environment to educate Tibetan monastics about environmental protection, and implementing environmental programs at Karma Kagyu monasteries and centres.

Under the Chinese state there is a different type of ‘green Tibetan’ discourse, which, in opposition to the account given by Tibetans in exile regarding the current situation in Tibet, portrays Tibetans as recipients of a ‘green science’ and technical knowhow for preserving the Tibetan landscape. No longer are they ‘passively adapted’ to the landscape as in ‘old’ Tibet but are in control of its preservation. At the same time, ‘sacred’ Tibetan knowledge is paid lip service by officials in places such as Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, where local deities and spirits have become part of this ‘green Tibetan’ discourse. For officials in Diqing, these entities are useful for their efforts to portray the area as a ‘lost Shangrila’ which these ‘gods’ have preserved in pristine condition. For transnational and local environmental NGOs, the promotion of mountain cults, together with an overlapping Tibetan Buddhism is important for their environmental conservancy efforts. Tibetan religious leaders have been ‘recruited’ by such NGOs to help educate locals about the importance of protecting the environment.

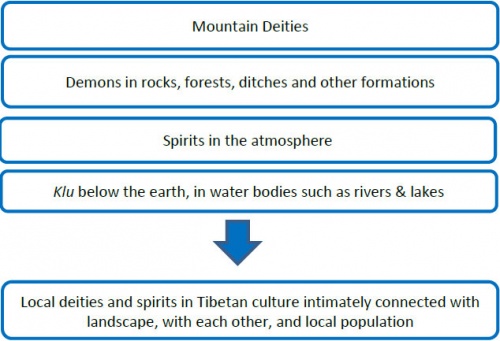

This paper examines the experiences of five Han Chinese and ethnic Tibetan practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism located in Beijing or Gyalthang (Eng – Shangrila, in Deqin Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province) in relation to their understanding of local Tibetan deities and spirits within the wider discourse of environmental protection in China. In traditional Tibetan belief these deities (e.g. mountain deities) and spirits inhabit every part of the Tibetan landscape, and are believed to be intimately connected with both the land and the people. Such entities are believed to provide blessings when their sacred abodes are not disturbed, and may exact severe punishment on those who cause damage to their habitat (e.g. by cutting down a tree from a sacred mountain). Many of these pre-Buddhist entities have been incorporated into Tibetan Buddhism as protectors of Buddhism in Tibet, and some are even believed to have become enlightened. This paper seeks to explore the perspectives of Han Chinese and ethnic Tibetan practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism regarding these entities; specifically, it seeks to ask whether the recent convergence of the ‘sacred knowledge’ that these entities symbolise with the discourse of environmental protection has weakened their position as fierce protectors of religion. That is, if these entities are simply drawn into the discourse of environmental protection and portrayed as primarily protectors of the environment rather than protectors of Buddhism, does their identity become secularised to an extent, and what does this mean for Tibetan Buddhism in general? Ultimately, I seek to show how the convergence of environmental protectionism with beliefs in local Tibetan deities and spirits, and the translocal and transnational forces which are influencing this convergence, is reflective of the wider adaptation of Tibetan Buddhism to contemporary Greater China and similar forces which are influencing this adaptation.

This paper is based on interviews with Han and Tibetan informants in 2011. I have chosen for this paper informants from both Beijing and Gyalthang to examine the differences in opinion between those living far from the Tibetan landscape to those living in close proximity to it, regarding local Tibetan deities and spirits in relation to the environmental protection movement. I seek to explore the role that distance from the Tibetan landscape plays in influencing the opinions of practitioners concerning local forms of Tibetan Buddhism, in addition to the backgrounds and translocal/transnational movements of these practitioners and the subsequent discourses to which they have been exposed. Although I only examine the experiences of five practitioners in this paper (due to lack of time), their experiences are nevertheless largely representative of the more than forty informants I interviewed on the mainland in Beijing and Gyalthang.

Objectives

To explore perspective of Han Tibetan Buddhists and ethnic Tibetan Buddhists towards local Tibetan deities and spirits.

To examine whether these deities and spirits retain their traditional roles in Tibetan belief, become subsumed within discourse of environmental protection, or take on both roles.

To ask how appropriation of these deities and spirits to discourse of environmental protection reflects wider local/transnational scope of Tibetan Buddhism in China.

Informants

5 Han and Tibetan practitioners

Province Proximity/distance:

- Demonstrates different

- understanding of place of local

- deities and spirits within

- Tibetan Buddhism

- as fierce protectors of religion

- tied closely to Tibetan landscape

- and people, as protectors of

- environment, or as both

Local Deities and Spirits in Tibetan Society

Green Tibetians: in Exile

- ‘Green Tibetan’ image: popular from mid-1980s onwards.

- Fact-finding reports carried out by delegations from Dharamsala to Tibet from 1979 to 1985.

- Participation of Tibetan leaders from Dharamsala in institutions promoting ‘religious environmentalist paradigm’.

Green Tibetans: in China

- Tibetans under Chinese state: recipients of ‘green’ science for preserving Tibetan landscape - no longer

‘passively adapted’ to landscape as in ‘old Tibet’.

- Officials in Diqing.

- Transnational and local NGO’s.

- 1998 ban on logging in northwest Yunnan Province – timber production has given way to ecotourism.

Case Samples

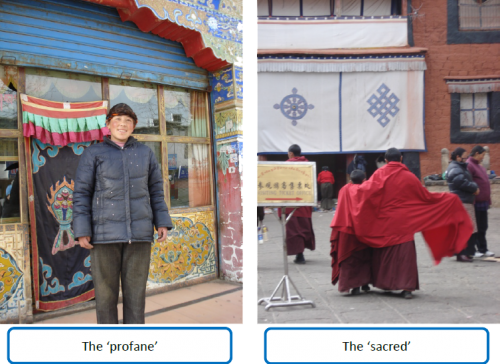

Experience roughly divided in two:

- All hybrid between these two spectrums to some extent

Circular Experience - ‘Tashi’

- A self-professed ‘atheist’ Tibetan monk from Yushu

- Became monk at 15

- Began shooting documentaries about Tibetan culture - went to America to study documentary-making professionally

- Mixed with mostly ‘secular’ friends at college – ‘atheist thoughts’ he had felt forming in Yushu ‘found a place’ in his mind, and he came to know how to ‘categorise’ himself

- Felt local deities and spirits may or may not exist – if exist in people’s minds environmental protection will be promoted

- ‘Things are constantly changing’ – attributing different roles to these entities is not detrimental to Buddhism

- However, resists ‘superstitious’ worship of unenlightened mountain deities ahead of Three Jewels of Buddhism (Buddha, Dharma, Sangha)

- Tashi’s ‘identity space’: monastery - college in Yushu - college in America – Yushu/Shangrila

- Carried ‘identity space’ of local deities and spirits

- Chinese Marxist thought, Western rationalism, local Diqing government portrayal of Shangrila as utopia, Buddhism as always being ‘deep ecology’

Mediated Experience - ‘Lin’

- ‘Lin’: Han practitioner and artist, together with husband, in a village outside Beijing

- From north-east China. She remembers all the ‘superstitious’ stories told in her village about spirits in rivers, lakes and trees

- She felt that these stories were ‘fake’ (jia de). However, she does believe the local deities and spirits of Tibet exist

- ‘Each protector protects the environment. Everything we have is from the environment, so we need to cherish and protect it…Nowadays we [ society ] focus on environmental protection but still see many natural disasters. In some ways it’s because of our sin, which damages the environment. We need to protect the local deities and be protected by them.’

- Lin’s belief in ‘spiritualised’ environment – more from popular belief in Taiwan and mainland China that environment has reciprocal relationship with humanity

- Lin sees local deities and spirits of Tibet as somewhat passive and weak, as ‘extras’ ‘added on’ to Buddhism after Guru Rinpoche arrived in Tibet

- ‘In Buddhism there were already many protector deities from India, and there was no need for additional protector deities, but Guru Rinpoche took the local deities and spirits in because they were like orphans.’

- Different to Tibetan accounts – local deities and spirits fierce, powerful beings related to Tibetan people

- Lin’s account: These ‘local’ deities and spirits almost totally detached from Tibet, its people and history

Eco-sublime Experience - ‘Zhang’

- ‘Zhang’: mixed Han-Mongol practitioner studying Buddhism and living in Shangrila

- He plans to remain in Shangrila to continue his studies indefinitely. He holds a Canadian passport, yet has no intention of returning to Canada, as he feels disillusioned with Western society

- Believes these local entities are protectors of Buddhism, but spoke more about them as embodiments of ‘ecological wisdom’, as ‘primordially’ connected to pristine landscape they protect:

- ‘Every blade of grass on the ground is holy, which matches the concept of Buddhism with protection of the environment. Many mountains have been designated [by lamas] as holy mountains to better protect them…I believe the land here is sacred, as the seven rivers [?] originate from this area. The plateau also rises above the surrounding land, and the scenery is amazing.’

- Tibetan Buddhism - ‘eco-sublime’ religion or spirituality which is ‘earth-inspired’ – Tibetan Buddhism draws on ‘charisma’ of Tibetan landscape, due to deities and spirits inhabiting it

Rebirth Experience – ‘Fei’

- ‘Fei’: more religiously-oriented and made little connection to discourse of environmental protection

- Worked for multi-million dollar company, before quitting her job to ‘enjoy’ life. She soon found this lifestyle meaningless, however. Her marriage suffered and she divorced

- Travelled about China and found her master in Shangrila. She now runs a hostel there and an orphanage in a nearby town

- Went on pilgrimage to Tibet in 2003 to visit monasteries and sacred mountains. Felt powerful presence of mountain deity at Mt Everest

- Said every Tibetan must circumambulate Mt Kawa Karpo at least once in his/her life, and Kawa Karpo provides protection for these pilgrims – those who circumambulated Kawa Karpo at least once had been spared during Yushu earthquake

- In 1991 a Sino-Japanese team of climbers perished while trying to climb it

- Fei believes she was Tibetan nomad in her past life: On auspicious days and during religious festivals she burns tsampa and juniper branches outside her house; has lost interest in money and material possessions; showers less often

- Tentative observation - those living in Tibetan areas more likely to engage closely with Tibetan population and ‘local’ elements of religion than those who remain for short time

Revival Experience – ‘Tsering’

- ‘Tsering’: a Tibetan ‘stay-home monk’ in Deqin

- Lived in Kunming, working for a law firm, where he became ‘more Chinese than Tibetan’

- Returned to Deqin for a month, met a lama at the local monastery who re-introduced him to Buddhism and his own culture

- Quit his job and moved back to Deqin – owns internet café, which he uses as base to teach Tibetan Buddhism to people all over China

- Tsering emphasised both traditional role of local deities and spirits, as well as compatibility of this traditional view with environmental protection

- He added:

- ‘Kawagebo is called grandfather in this area. He is a part of our family.’

- He is on committee of the Kawagebo Cultural Society, which emphasises protection of the environment by preserving mountain cults. However, he emphasised we cannot simply reduce mountain deities to environmental protectors

- ‘If we say they [ environmental protectionists ] have to protect the mountain, it makes the mountain deity weak. He has no need for our protection. The mountain deity has the ability to protect us and we have the ability to protect it only to a limited extent – so it is an equal relationship. In Buddhism all things are equal. The mountain gives meaning to the people and the people give meaning to the mountain...If you do something wrong against Buddhism, Kawagebo will punish you. This idea helps people to maintain morality as well as protect the environment. ‘

Conclusion

Perspective of informants regarding local deities and spirits reflects wider trend of Tibetan Buddhism in China among Han and Tibetans:

- a) Circulated Tibetan Buddhism

- b) Mediated Tibetan Buddhism

- c) Eco-sublime or ‘earth-inspired’ Tibetan Buddhism

- d) Rebirth-experience Tibetan Buddhism

- e) Revived Tibetan Buddhism

Above trends show how Tibetan Buddhism is going out and coming back; is being received through media outside mainland; is being experienced through pilgrimage; is being explored through lived experience of Han working in Tibetan areas; is experienced through psychology of rebirth; and is being revived through a process of negotiation between ‘modern’ and ‘traditional’ worldviews.

Footnotes

- ↑ The separation of these discourses into territories is for convenience here, as there is some overlap of these discourses in these territories, and these are not the only discourses being appropriated and hybridised with Tibetan Buddhism; I have singled out these discourses due to their dominant influence in the abovementioned locations.

Source

Joshua Esler, University of Western Australia

The third International Conference Buddhism & Australia 2014