Lojong

Lojong (Tib. བློ་སྦྱོང་,Wylie: blo sbyong) is a mind training practice in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition based on a set of aphorisms formulated in Tibet in the 12th century by Geshe Chekhawa.

The practice involves refining and purifying one's motivations and attitudes. lojong: "Seven points in training the mind" teachings brought to Tibet by Atisha.

The fifty-nine or so slogans that form the root text of the mind training practice are designed as a set of antidotes to undesired mental habits that cause suffering.

They contain both methods to expand one's viewpoint towards absolute bodhicitta, such as "Find the consciousness you had before you were born" and "Treat everything you perceive as a dream",

and methods for relating to the world in a more constructive way with relative bodhicitta, such as "Be grateful to everyone" and "When everything goes wrong, treat disaster as a way to wake up."

Prominent teachers who have popularized this practice in the West include Pema Chodron, Ken McLeod, Alan Wallace, Chogyam Trungpa, Sogyal Rinpoche, Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, and the 14th Dalai Lama.

History of the practice

Lojong mind training practice was developed over a 300-year period between 900 and 1200 CE, as part of the Mahāyāna school of Buddhism. Atiśa (982–1054 CE), a Bengali meditation master, is generally regarded as the originator of the practice.

It is described in his book Lamp on the Path to Enlightenment (Bodhipathapradīpaṃ).

The practice is based upon his studies with the Sumatran teacher, Dharmarakṣita, author of a text called the Wheel of Sharp Weapons. Both these texts are well known in Tibetan translation.

Atiśa journeyed to Sumatra and studied with Dharmarakṣita for twelve years. He then returned to teach in India, but at an advanced age accepted an invitation to teach in Tibet, where he stayed for the rest of his life.

A story is told that Atiśa heard that the inhabitants of Tibet were very pleasant and easy to get along with. Instead of being delighted, he was concerned that he would not have enough negative emotion to work with in his mind training practice.

So he brought along his ill-tempered Bengali servant-boy, who would criticize him incessantly and was challenging to spend time with.

Tibetan teachers then like to joke that when Atiśa arrived in Tibet, he realized there was no need after all.

The aphorisms on mind training in their present form were composed by Chekawa Yeshe Dorje (1101–1175 CE).

According to one account, Chekhawa saw a text on his cell-mate's bed, open to the phrase: "Gain and victory to others, loss and defeat to oneself".

The phrase struck him and he sought out the author Langri Tangpa (1054–1123). Finding that Langri Tangpa had died, he studied instead with one of Langri Tangpa's students, Sharawa, for twelve years.

Geshe Chekhawa is claimed to have cured leprosy with mind training.

In one account, he went to live with a colony of lepers and did the practice with them. Over time many of them were healed, more lepers came, and eventually people without leprosy also took an interest in the practice.

Another popular story about Geshe Chekhawa and mind training concerns his brother and how it transformed him into a much kinder person.

The Root Text

- The original Lojong practice consists of 59 slogans, or aphorisms. These slogans are further organized into seven groupings, called the '7 Points of Lojong.'

The categorized slogans are listed below, translated by the Nalanda Translation Committee under the direction of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

It is emphasized that the following is translated from ancient Sanskrit and Tibetan texts, and therefore may vary slightly from other translations. Some slogans may feel esoteric or difficult to comprehend.

Many contemporary gurus and experts have written extensive commentaries elucidating the Lojong text and slogans. Some of these works can be found under the 'Notes' section of this article.

Point One: The preliminaries, which are the basis for dharma practice

- Slogan 1. First, train in the preliminaries; The four reminders. or alternatively called the Four Thoughts

- 1. Maintain an awareness of the preciousness of human life.

- 2. Be aware of the reality that life ends; death comes for everyone; Impermanence.

- 3. Recall that whatever you do, whether virtuous or not, has a result; Karma.

- 4. Contemplate that as long as you are too focused on self-importance and too caught up in thinking about how you are good or bad, you will experience suffering. Obsessing about getting what you want and avoiding what you don't want does not result in happiness; Ego.

Point Two: The main practice, which is training in bodhicitta.

- Slogan 2. Regard all dharmas as dreams; although experiences may seem solid, they are passing memories.

- Slogan 3. Examine the nature of unborn awareness.

- Slogan 4. Self-liberate even the antidote.

- Slogan 5. Rest in the nature of alaya, the essence, the present moment.

- Slogan 6. In postmeditation, be a child of illusion.

- Slogan 7. Sending and taking should be practiced alternately. These two should ride the breath (aka. Practice Tonglen).

- Slogan 8. Three objects, Three poisons|three poisons, three roots of virtue -- The 3 objects are friends, enemies and neutrals. The 3 poisons are craving, aversion and indifference. The 3 roots of virtue are the remedies.

- Slogan 9. In all activities, train with slogans.

- Slogan 10. Begin the sequence of sending and taking with yourself.

Point Three: Transformation of Bad Circumstances into the Way of Enlightenment

- Slogan 11. When the world is filled with evil, transform all mishaps into the path of bodhi.

- Slogan 12. Drive all blames into one.

- Slogan 13. Be grateful to everyone.

- Slogan 14. Seeing confusion as the four kayas is unsurpassable shunyata protection.

- The kayas are Dharmakaya, sambhogakaya, nirmanakaya, svabhavikakaya. Thoughts have no birthplace, thoughts are unceasing, thoughts are not solid, and these three characteristics are interconnected. Shunyata can be described as "complete openness."

- Slogan 15. Four practices are the best of methods.

- Slogan 16. Whatever you meet unexpectedly, join with meditation.

Point Four: Showing the Utilization of Practice in One's Whole Life

- Slogan 17. Practice the five strengths, the condensed heart instructions.

- The 5 strengths are: strong determination, familiarization, the positive seed, reproach, and aspiration.

- Slogan 18. The mahayana instruction for Phowa|ejection of consciousness at death is the five strengths: how you conduct yourself is important.

- When you are dying practice the 5 strengths.

Point Five: Evaluation of Mind Training

- Slogan 19. All dharma agrees at one point -- All Buddhist teachings are about lessening the ego, lessening one's self-absorption.

- Slogan 20. Of the two witnesses, hold the principal one -- You know yourself better than anyone else knows you

- Slogan 21. Always maintain only a joyful mind.

- Slogan 22. If you can practice even when distracted, you are well trained.

Point Six: Disciplines of Mind Training

- Slogan 23. Always abide by the three basic principles -- Dedication to your practice, refraining from outrageous conduct, developing patience.

- Slogan 24. Change your attitude, but remain natural.-- Reduce ego clinging, but be yourself.

- Slogan 25. Don't talk about injured limbs -- Don't take pleasure contemplating others defects.

- Slogan 26. Don't ponder others -- Don't take pleasure contemplating others weaknesses.

- Slogan 27. Work with the greatest defilements first -- Work with your greatest obstacles first.

- Slogan 28. Abandon any hope of fruition -- Don't get caught up in how you will be in the future, stay in the present moment.

- Slogan 29. Abandon poisonous food.

- Slogan 30. Don't be so predictable -- Don't hold grudges.

- Slogan 31. Don't malign others.

- Slogan 32. Don't wait in ambush -- Don't wait for others weaknesses to show to attack them.

- Slogan 33. Don't bring things to a painful point -- Don't humiliate others.

- Slogan 34. Don't transfer the ox's load to the cow -- Take responsibility for yourself.

- Slogan 35. Don't try to be the fastest -- Don't compete with others.

- Slogan 36. Don't act with a twist -- Do good deeds without scheming about benefiting yourself.

- Slogan 37. Don't turn gods into demons -- Don't use these slogans or your spirituality to increase your self-absorption

- Slogan 38. Don't seek others' pain as the limbs of your own happiness.

Point Seven: Guidelines of Mind Training

- Slogan 39. All activities should be done with one intention.

- Slogan 40. Correct all wrongs with one intention.

- Slogan 41. Two activities: one at the beginning, one at the end.

- Slogan 42. Whichever of the two occurs, be patient.

- Slogan 43. Observe these two, even at the risk of your life.

- Slogan 44. Train in the three difficulties.

- Slogan 45. Take on the three principal causes: the teacher, the dharma, the sangha.

- Slogan 46. Pay heed that the three never wane: gratitude towards one's teacher, appreciation of the dharma (teachings) and correct conduct.

- Slogan 47. Keep the three inseparable: body, speech, and mind.

- Slogan 48. Train without bias in all areas. It is crucial always to do this pervasively and wholeheartedly.

- Slogan 49. Always meditate on whatever provokes resentment.

- Slogan 50. Don't be swayed by external circumstances.

- Slogan 51. This time, practice the main points: others before self, dharma, and awakening compassion.

- Slogan 52. Don't misinterpret.

- The six things that may be misinterpreted are patience, yearning, excitement, compassion, priorities and joy. You're patient when you're getting your way, but not when its difficult.

You yearn for worldly things, instead of an open heart and mind. You get excited about wealth and entertainment, instead of your potential for enlightenment.

You have compassion for those you like, but none for those you don't.

Worldly gain is your priority rather than cultivating loving-kindness and compassion. You feel joy when you enemies suffer, and do not rejoice in others' good fortune

- Slogan 53. Don't vacillate (in your practice of LoJong).

- Slogan 54. Train wholeheartedly.

- Slogan 55. Liberate yourself by examining and analyzing: Know your own mind with honesty and fearlessness.

- Slogan 56. Don't wallow in self-pity.

- Slogan 57. Don't be jealous.

- Slogan 58. Don't be frivolous.

- Slogan 59. Don't expect applause.

Commentaries

One seminal commentary on the mind training practice was written by Jamgon Kongtrul (one of the main founders of the non-sectarian Rime movement of Tibetan Buddhism) in the 19th century.

This commentary was translated by Ken McLeod, initially as A Direct Path to Enlightenment.

This translation served as the root text for Osho's Book of Wisdom.

Later, after some consultation with Chogyam Trungpa, Ken McLeod retranslated the work as The Great Path of Awakening.

Two significant commentaries to the root texts of mind training have been written by Geshe Kelsang Gyatso (founder of the New Kadampa Tradition) and form the basis of study programs at NKT Buddhist Centers throughout the world.

The first, Universal Compassion is a commentary to the root text Training the Mind in Seven Points by Geshe Chekhawa.

The second, Eight Steps to Happiness is a commentary to the root text, Eight Verses of Training the Mind by Geshe Langri Tangpa.

In 2006, Wisdom Publications published the work Mind Training: The Great Collection (Theg-pa chen-po blo-sbyong rgya-rtsa)}}, translated by Thupten Jinpa.

This is a translation of a traditional Tibetan compilation, dating from the fifteenth century, which contains altogether forty-three texts related to the practice of mind training.

Among these texts are several different versions of the root verses, along with important early commentaries by Se Chilbu, Sangye Gompa, Konchok Gyaltsen, and others.

Source

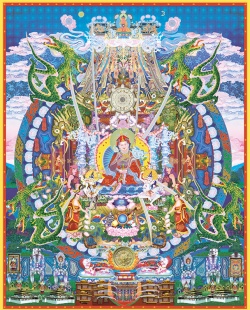

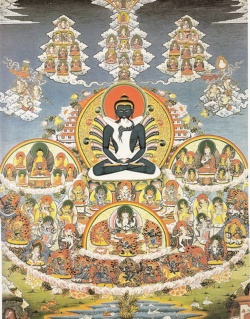

[[image:Atisha.JPG|frame|Jowo Jé Glorious Atisha)]

Lojong (Tib. བློ་སྦྱོང་, Wyl. blo sbyong) — literally ‘training the mind’, or ‘transforming the mind’.

These teachings, which emphasize the practice of bodhichitta and especially relative bodhichitta and the 'exchanging oneself for others', were introduced to Tibet by Lord Atisha in the eleventh century.

Unlike the lamrim teachings, which were also introduced by Atisha at the same time, and which can be practiced by anyone, the lojong teachings are intended primarily for disciples of the highest capacity and were not taught widely until the time of Geshe Chekawa.

Literal meaning

The word lo means mind, but specifically the untamed thinking mind.

Jong can mean to learn, exercise, train, purify or refine.

Zenkar Rinpoche explains that in this context jong means to use powerful remedies or antidotes in order to subjugate, tame or transform the mind.[1]

These powerful remedies, which include both skilful means and wisdom are employed to subjugate the self-clinging, based on a false conception of self, that is at the root of all suffering.

The wisdom methods, such as meditative analysis, lead to the realization of selflessness,

while the skilful means focus on the development of great compassion,

through the meditative practices of equalizing ourselves and others (bdag gzhan mnyam pa),

exchanging ourselves and others (bdag gzhan brje ba)

and considering others as more important than ourselves (bdag las gzhan gces pa).

Footnotes

- ↑ Alak Zenkar Rinpoche, Haileybury, 12 April 2012

Further Reading

- Geshe Thupten Jinpa (translator), Mind Training: The Great Collection (as part of an anthology of early lojong texts), Wisdom Publications, 2005

See Also

- Eight Verses of Training the Mind

- Seven Points of Mind Training

- Tonglen

- The Wheel Blade of Mind Transformation