Urga, February 1921

During the Russian Civil War Baron von Ungern-Sternberg earned a reputation in Siberia as a sadistic warlord whose excesses did more harm to his own side than to his Communist enemies. When the anti-Bolshevik forces collapsed in 1920 the

Baron took his men over the border to Chinese-controlled Mongolia. CHRISTOPHER OTHEN, author of 'FRANCO'S INTERNATIONAL BRIGADES: ADVENTURERS, FASCISTS, AND CHRISTIAN CRUSADERS IN THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR', looks at the Baron's capture of the Mongolian capital {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}}, the first – and last –step of a crazed attempt to build a Buddhist Empire stretching from Mongolia to Portugal.

Baron Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, the Bolshevik Revolution, and the Birth of Modern Mongolia

‘Spring was here and with it were coming new horrors of battle, destruction, fire and painful death. The earth was in blossom but we were polishing our rifles and sharpening our knives. Soon we would begin to kill again.’ – Dimitri Alioshin1

The Mongolian capital {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} sat on the banks of the Tuul river in the bowl of a valley formed by the four mountain peaks of Bogdo Ul, Songino Khairkhan, Chingeltei and Bayanzurh, all part of the Khan Khentui range. The town was founded in 1639 but suitably for the capital of a nomadic nation only settled in its current location in the

central east of the country, a pivotal position on the old Tea Road that took overland trade between Peking and St Petersburg, in 1778. Urga was the Russian name for the town. In the Baron’s time the Mongolians knew it as Niislel Khuree (1911-1924); previously they called it Orgoo (1639-1706) and Ikh Khuree (1706-1911).

In 1921 the population of Urga was estimated at 70,000. Mongolia’s capital was a ramshackle sweep of one storey wooden houses and gers (circular felt huts with conical roofs called yurts by the Russians) punctuated by Chinese warehouses, Russian town houses and the elaborate gold leafed towers of Buddhist temples. The wide dirt roads baked solid in summer but were muddy slush through most of winter. Originally a religious town built around monasteries, temples and the palaces of the Living Buddha {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} formed a second identity as a commercial hub for the Chinese when it relocated to the Tuul.

Mongolians were a nomad people because the land had little to offer them; the sparse grazing kept herdsmen moving their cattle, horses and camels across the country through the year. In summer they trekked across the never ending steppes; in the distance forest-covered hills led up into mountains. In winter the landscape was blotted out by snow. The temperature could reach as high as 38°C (94°F) in the summer and drop to -49°C (-46°F) in winter.

In the north east of Mongolia was a small provincial town called Kharhorin. Shabby buildings housed the few permanent residents. There was little to see apart from a ‘phallic rock’, popularly believed to be a magical deterrent that prevented local monks giving into their carnal urges. In the 13th century this primitive backwater had been the central point of

the largest empire the world has ever seen. Kharkorin was Ghengis Khan’s (1162-1227) decreed capital of the Mongolian Empire, a territory which would stretch at its height from China through Russia and into Hungary. Mongolian warriors on horseback looted, raped and pillaged their way

across Asia and Europe and no army was strong enough to stop them. The capital was moved to what is now Beijing in China by Kublai Khan during the 1260s; during the 14th century the imperial realm created by Ghengis Khan (a title meaning Universal King – his real name was Temujin) retracted then collapsed. The empire shrank back to the borders of Mongolia and the capital returned to Kharkhorin.

In the seventeenth century Chinese troops from Manchuria burnt Kharkhorin to the ground to punish a resurgence of Mongolian nationalism. The provincial town re-built on the site was a pale shadow of former glory. {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} became the unchallenged centre of religious and secular power in the country.

Buddhism

The adoption of Lamaist Buddhism (the ‘Yellow Faith’) as the official religion of the country was an attempt by Altan Khan (1543-82) to unify the warring clans and ethnic groups left in the aftermath of the empire’s collapse. Mongolia had always been religiously tolerant, with Buddhism, Islam and other faiths co-existing peacefully. Altan Khan felt that Buddhism could best provide the spiritual cohesiveness to bring the county together in the face of the increasing

threat from China. He invited Sodnomjamtso, the religious leader of Buddhist Tibet, to Mongolia and elevated him to head of the Yellow Faith. Sodnomjamtso received the title of Dalai Lama (Dalai is Mongolian for Ocean); in return for their official adoption of Buddhism the third Dalai Lama was found reborn in Mongolia and the fourth was a nephew of Altan Khan.

This new found religious unity slowed but could not stop the inevitable Chinese take over of the country by the end of the seventeenth century. Emperor Xang Xi of the Manchu Qing dynasty divided the country into Inner Mongolia on the Chinese border, which he annexed, and Outer Mongolia bordering Russia and China, which he subdued and governed as an ‘autonomous region’. The autonomous region was effectively a buffer zone against Russia in the north and the Chinese rulers concentrated their imperialist efforts on absorbing Inner Mongolia into China.

Members of the Mongolian aristocracy and Buddhist theocracy collaborated in the occupation, seeing a chance for order and personal advancement; Chinese settlers, farmers and merchants swarmed over the border. The son of the Mongol Khan of Urga was named a reincarnation of the

‘Living Buddha’ to ensure the loyalty of the Buddhist heirachy to their new rulers. There were three heads of Lamaist Buddhism: the Dalai Lama in Tibet oversaw its administration, the Panchen Lama in Tibet was its spiritual leadership and the Living Buddha was the reincarnation of the Buddha himself. After 1650 all Living Buddhas were brought to Urga.

For the next two hundred years Mongolia settled down into the slow pace of Chinese rule. There was increased trade and a certain degree of prosperity but for majority of Mongolians (most of whom were herdsmen and their families) life went on as before.

Trade opened up with Russia through the Kiakhta Treaty of 1727 but both China and Russia were nervous of encouraging too much contact with Mongolia. The Chinese thought it would encourage Russian territorial ambitions, the Russians that it would give hope to the nationalist ambitions of the Buryats – a

Mongolian people who ended up on the Russian side of the border in the fall out from the collapse of the empire. Both had good reasons for their concerns: despite the efforts of the Chinese and their collaborators the flame of Pan-Mongolism still burned. There were many who dreamed of an Independent Mongolia with enlarged territory that embraced Mongols both in China and Russia.

[[Wikipedia:Chinese Revolution|Chinese Revolution]]

In 1911 there was a revolution in China. The overthrow of the Qing dynasty pushed China into an abrupt collapse from which it would emerge as a chaotic republic. Outer Mongolia took the opportunity to declare independence under its current Living Buddha (1870-1924) – a Tibetan, gone blind through syphillis, known as{{Wiki| [[Wikipedia:Bogdo Geghen (Great Saint), Bogdh Khan (Holy King) or the Koutouktou (the Reincarnated One) – and turned to Russia for help. Tsarist Russia recognised the country’s ’autonomy’ but not its independence.

Along with worries about the Buryats and its own ambitions to rule Mongolia, secret treaties at the end of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 forced Russia to accept Mongolia lay within Japan’s sphere of influence. Despite this, Russia managed to supply weapons, munitions and experts in the fight against the Chinese. Russian army officers served terms in the Mongolian Army – among them a 24-year-old Baltic German called Baron Roman Feodorovitch von Ungern-Sternberg.2

The Russo-Japanese Convention of 1912 shifted Japanese influence to Inner Mongolia while the Russo-Mongolian Treaty of the same year vastly increased Russian power in the country. It obtained extensive mining and trade concessions; its citizens enjoyed extra-territorial rights. In {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} a large Russian colony emerged; it had its own bank – the [[Wikipedia:Russo-Mongolian

Commercial Bank|Russo-Mongolian

Commercial Bank]] run by Dimitri Pershin (1861-1936), a well known literary figure under the name Dimitri Daursky as well as banker – and they dominated the foreign settlement of the town. Valuable sections of Mongolia, such as the Altai District, were detached and placed under Russian rule. In the interests of diplomacy China was even allowed to retain a symbolic military presence in Outer Mongolia.

The Mongolians had obtained autonomy at a price but they were aware it depended on a strong Russia to protect them. That strength began eroding with the start of the First World War in 1914; over the next few years the Russian Army suffered huge losses against German and Austro-Hungarian forces. Behind the lines Russian civil society began to slowly crack up. The population could not support the attrition of war and the inequalities of privilege in a country not far out of feudalism.

When the shockwaves of the 1917 Revolutions knocked the Russian Army out of the war the Chinese were able to re-occupy Outer Mongolia. They confined the Bogdh Geghen, Mongolia’s nominal leader, to his palaces in {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} and stamped down on any signs of nationalism. Chinese merchants returned to the town, a Chinese administration took over and a garrison of Chinese soldiers kept order. The clock had been turned back.

The Living Buddha

The Living Buddha’s place of confinement was dictated to him by his lamas. They chose which of the three palaces – one green, one white, one red – situated on the hills around the city he should live in. When their teachings decreed he moved on to the next one. On his trips up into the hills the Living Buddha would have had excellent views of {{Wiki:UlanBator|Urga}}, if he had not gone blind from venereal disease contracted through his bisexual orgies.

The palaces were tribute to the [[Wikipedia:Jebtsundamba Khutuktu|Bogdo Geghen]]’s materialist tastes. Russian soldier Dimitri Alioshin saw them during his service with the Baron’s army. ‘Here all the luxuries of Asia mingled with the objects of Western civilisation,’ he later wrote. ‘Phonographs, pianos, chemical apparatus, surgical instruments, guns of various types, collections of clocks, automobiles with bodies especially designed to resemble the palanquins of Chinese emperors.’3

The temple of Maidari with its eighty foot high Tibetan towers stood in the centre of the town. Outside its doors a huge gilded Buddha statue sat on the golden flower of a lotus. The building contained the Living Buddha’s throne room. The central part of {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} was made up of golden domed temples (datzans) served by fifteen thousand lamas; prayer wheels set outside chimed a bell each time they were turned a full circle. Pilgrims came from all over Mongolia to worship. Around them were palisaded compounds, schools, libraries and living quarters – single story brick and gers – for the lamas.4

The Chinese section of the town was principally populated by merchants; they built Chinese style houses and trading establishments for themselves. In the foreign settlement the Russian houses and administrative blocks were dominated by the Byzantine cupolas of an Orthodox church. The local gold mines in Dzumodo, north of Urga, were run from the Mongolor sector. The town was widely spread out on both banks of the river and in some areas open countryside separated different districts.

There were street markets throughout the city. Cattle, wool, saddles, meat, painted glass snuff bottles (a social necessity – it was traditional to sample snuff with your host when staying in his ger), hay, coral beads and silk were sold or bartered in a fast moving flood of Mongols, Chinese, Buryats, Russians and other foreigners. Caravans of camels plodded through the streets. Lamas in yellow or red robes wandered through the crowds spying on new arrivals and picking out those rich enough to afford their fortune telling skills.

Fortune telling was ubiquitous in Mongolia. As mutton was the staple diet the most common method was to use the shoulder blade of a sheep and scrape it clean of flesh. The bone was left in the coals of a fire until it blackened; it was then removed, cleaned of ash and the surface of the burnt bone studied. Skilled fortune tellers could predict a man’s death in the smoky cracks and patterns. Other methods included using the entrails of a sheep.5 After months in Mongolia the Baron’s men went native and units elected their own mediums who used shoulder blades, cards, palms and moving saucepans to predict the outcome of battles.

Ferdinand Ossendowski (1876-1945), a Polish geologist and explorer with the respectable counter-revolutionary pedigree of having been finance minister for Admiral Kolchak in Siberia, arrived at {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} in May 1921 after it had fallen to the Baron. On his first day he visited the markets.

‘To the lively coloured groups of men buying, selling and shouting their wares, the bright streamers of Chinese cloth, the strings of pearls, the earrings and bracelets gave an air of endless festivity; while on another side buyers were feeling live sheep to see whether they were fat or not, the butcher was cutting great pieces of mutton from the hanging carcasses and

everywhere these sons of the plain were joking and jesting. The Mongolian women in their huge coiffures and heavy silver caps like saucers on their heads were admiring the variegated silk ribbons and long chains of coral beads; an imposing big Mongol attentively examined a small herd of splendid horses and bargained with the Mongol zahachine or owner of the horses’.6

The back streets of {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} functioned as a waste disposal system. Inhabitants defecated and urinated in public, crouching in groups on the curb to chat while they did. Buddhist ideas on the immortality of the soul allowed dead or dying bodies of native Mongolians to be left in the street; they were regarded as the meat left behind once the soul had flown to reincarnate.

At night the wild dogs of Urga came out and ate everything, gulping down excrement then devouring the decaying flesh of the corpses and splintering the bones. The houses of the Russia quarter, some Chinese merchants’ homes and the palaces of the Living Buddha had toilets and other facilities but the majority of Urga’s population trusted to the dogs.

After dark the dogs would attack anyone not carrying lantern and during the day it was a sensible precaution to carry a stick tipped with an iron spike to drive them off if they made an appearance. Henning Haslund-Christiansen, a Swedish explorer who visited {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} in 1927, reported: ‘Dogs everywhere prowl, everywhere there is filth, heaps of garbage and an unbelievable stench’.7 Outside of the town bodies were thrown into rivers, hung from trees or left on the steppes for the wolves.

Some of the more modern buildings had electricity and there was a small telephone network run through a central exchange with over a hundred users. Among the modern pleasures available to inhabitants were silent films brought occasionally from Russia and displayed in makeshift cinemas.8

The Baron Returns

During the night of 31st January 1921 hundreds of bonfires were lit in the hillsides around Urga. The Chinese garrison began to panic. The Bloody Baron had returned.

The Asiatic Cavalry Division (Aziatskaia Konnaia Diviziia) of Baron Roman Feodorovitch von Ungern-Sternberg first besieged Urga in October 1920. Four attempts to take the town were beaten back by superior numbers of well dug in Chinese troops.

The Division retreated back into the steppes to regroup, recruit fresh troops and make contact with native Mongolian nationalists. When they returned the Chinese authorities already knew the clique of lamas around the Living Buddha were plotting with the Baron from inside Urga. The nervous Chinese tightened security around the lamas; some Russians in the town were imprisoned, others were shot. In the hills, the Baron waited for his native fortune tellers to tell him the correct time to attack.

How many of the people in Urga that night knew who the Baron was? The Russians who had sat out the civil war in Mongolia knew him vaguely as a White Army commander with a dark reputation. Their knowledge was updated by refugees from the fall of Admiral Kolchak’s Siberian state in the winter of 1919. To them Baron Ungern-Sternberg was a cancer in the White cause.

Along with his friend Cossack Attaman Gregori Semenov (1887–1946) the Baron had ruled as a private warlord behind the lines, robbing trains of supplies heading up to the front, extorting money from anyone passing through his area and refusing to co-operate with Kolchak in his fight against the Red Army. Ex-Kolchak soldiers, who had fought in rags while Semenov’s men diverted equipment

intended for them to their own use, were the most bitter. They were also the most desperate. The majority had been rounded up by the Chinese and were being held in medieval conditions in the town’s jail. Those Russians still free were afraid of a Chinese pogrom against them. Cancer or not, they needed his help.

The Mongolians in {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} saw the Baron as the catalyst for their independence. The imprisonment of the Living Buddha and maltreatment of lamas had outraged the population and turned previous collaborators against the Chinese. They wanted the Asiatic Cavalry Division and its Mongolian auxiliaries to drive out the occupiers and bring

freedom. The news that the Baron’s men had rescued the Living Buddha from the Chinese after an assault on his palace in the hills was greeted with joy. Even a proto-Communist cell based around Mongolian workers in the Russian consulate translation school was eager for the Baron to attack. The Chinese knew nothing

about the Baron except for a suspicion he was a tool of the Japanese. After the attacks in October Marshal Chang Tso-Lin had been given $500,000 by the Chinese government to equip and send reinforcements; in a typical piece of warlord corruption the Marshal took the money but the reinforcements stayed at home.9

Early confidence from the Baron’s first defeat led to complacency in the garrison ruled by General Chu. Joseph Galeta, a Hungarian soldier taken prisoner of war by the Russians in 1917 and struggling through an exotic nine year journey back to his homeland, was told by senior Chinese officers that the Bogdo Ul mountain would halt the Baron.

Galeta, who was employed by the Chinese to manufacture mines, thought they were ‘just children, without the least notion of the capacity of a modern army or to what extent they had to fear Baron Ungern-Sternberg. When the Baron made it over Bogdo Ul Chinese morale dropped dramatically.10 They now believed he had returned as the spearhead of a larger army, bolstered by troops from the Crimea and Siberia. They were wrong but the governor of {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} had already fled and the nearest relief force was eight hundred miles away - and refusing to advance any further because of the weather.

Monarchist Revolutionary

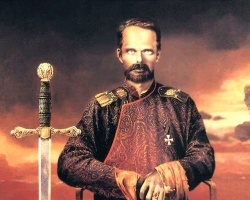

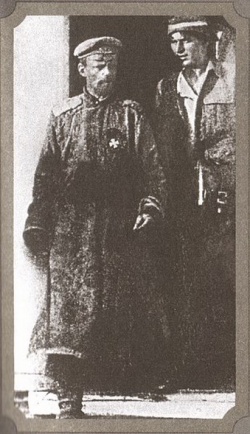

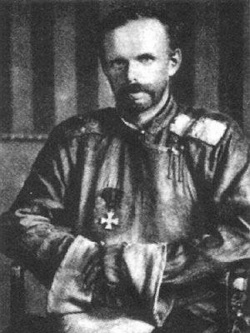

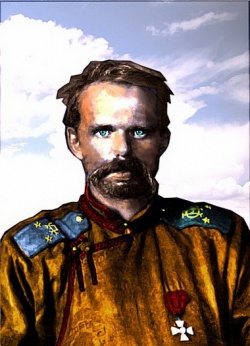

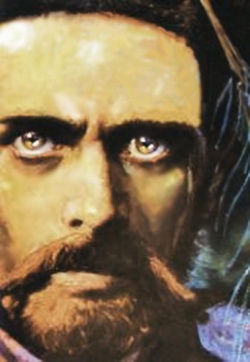

The focus of these fears and hopes was thirty five years old in 1921 and had spent most of his life in military service. Baron von Ungern-Sternberg was tall, with reddish blond hair and a large cavalry moustache. His light blue

eyes were set in a piercing stare under a prominent forehead slashed with a scar from a sword blow. He was the product of hundreds of years of Teutonic in-breeding. His martial ancestors had been the point of the Russian Empire’s sword since the thirteenth century. Before serving the Tsar they had carved an Empire out of the Baltic states, introduced [[Wikipedia:Christianity|Christianity]] to the pagan populations and made them into serfs.

The Baron’s men never understood him. The rank and file were terrified of the punishments he handed out for minor transgressions: soldiers who displeased him would be lucky to escape with having their backs beaten to a bloody pulp by a split bamboo cane.

He was close to only a few officers and none of those who knew him on a deeper level survived Mongolia. Memoirs published later by members of the Asiatic Cavalry Division and others who met him in {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} show admiration over shadowed by a struggle to understand his personality. They saw the visionary as well as the sadist in him but never understood how they co-existed or related. The Bolsheviks claimed he was an arch reactionary in their propaganda, painting him as an old style

Russian Imperialist dedicated to bringing back the oppressive feudalism of Tsarist society. Like all good propaganda there are elements of truth - but in his core beliefs the Baron was just as revolutionary as the Politburo. He believed the West was irretrievably decadent: a cesspool of democracy, comfort and tolerance. It had to be destroyed by fire. He believed in tradition, the eternal Buddhist wisdom of the Asiatic people and the redeeming power of war.

The Baron was born to an aristocratic family of Baltic Germans in Graz, Austria and brought up in Reval, Estonia; he fought in the Russian and Mongolian armies, travelled the Russian Far

East, joined the Cossacks for the First World War in which he was wounded five times and became a Siberian warlord in the Russian Civil War. He was an authoritarian, did not care about his physical comfort and was indifferent to the suffering of others. As he waited in the hills above {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} his ultimate goal was across the border in another country; he believed it was his destiny to return Russia to a year zero of Buddhist simplicity through the use of cleansing force under a new Tsar. The taking of Mongolia was his first step.

Physically he made a striking impression. ‘[He had] a small head on wide shoulder,’ wrote Ossendowski, ‘blonde hair in disorder; a reddish bristling moustache; a skinny, exhausted face, like those on the old Byzantine ikons. Then everything else faded from view save a big, protruding forehead overhanging steely sharp eyes. These eyes were fixed upon me like those of an animal from a cave.’11

Alioshin saw him face to face only once at a recruiting station inspection. The Baron was ‘tall and slim, with the lean white face of an ascetic. His watery blue eyes were steady and piercing. He possessed a dangerous power of reading people’s thoughts. A firm will and unshakeable determination possessed those eyes to such an extent that they suggested ominous insanity. I felt a cold shiver

run up my back when I saw them. He had unusually long hands and an abnormally small head resting on a pair of large shoulders. His broad forehead bore a terrible sword cut which pulsed with red veins. His white lips were closed tightly, and long blond whiskers hung in disorder over his narrow chin. One eye was a little above the other’.12

In the best known of the few photographs available of Ungern-Sternberg he wears an elaborate patterned Mongolian robe with Russian general’s epaulettes and the cross of St George medal he earned in the First World War pinned to the left breast. The outfit was a gift from the Bogdh Khan for his coronation and the Baron wore it proudly but he

was generally indifferent to clothes or physical comfort; typically he wore whatever was practical. When Ossendowski saw him returning from an ambush against a Chinese relief column in May he was wearing a red silk Mongolian coat.13 Before the attack on {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}}: he wore ‘a dirty papaha [tall woolly sheepskin hat], a short Chinese silk jacket of a cherry-red colour, blue military breeches and high

Buriat riding boots’. 14 At other times he wore an uncared for Russian military uniform.

The Baron’s Asiatic Cavalry Division was one of the last coherent parts of the White Russian Armies, a heterogeneous movement of monarchists, democrats, anti-semites, social revolutionaries, imperialists and nationalists that failed to overthrow the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia.

The Whites were the best and worst of Tsarist Russia: chivalrous, dedicated and brave but corrupt, lazy and ignorant. They nearly won. In late 1919 the Don Armies in the South planned to be in Moscow by Christmas and Admiral Kolchak’s Siberian forces were rolling up Bolshevik territory on a 750 mile long front. But the wave collapsed, the armies atomised and, within months, victims of the disaster like the former general waiting tables in a Paris restaurant and the exiled Russian noblewoman prostituting her daughters on a Harbin sidestreet were stock figures for journalists.

The Division had escaped the catastrophic collapse of Kolchak’s forces because they had been sent on a mission by Ataman Semenov to lay the foundations of a planned pan-Mongolian republic shortly before the White Army’s lines broke during the winter of 1919. Semenov’s territory at the extreme east of Siberia survived to October 1920 because of Japanese military support but by the time the Baron finally took power in Mongolia and tried to put the plan into effect Semenov was impotently plotting in Port Arthur and his malnourished men were squatting in railway carriages near Vladivostok.

The Division was a 1,470 strong multicultural mixture of Cossack, Russian, Mongolian, Buryat, Tartar, Japanese and others. It was made up of two regiments (Tatar Regiment of 350 men, Annenkov regiment of 300), three native Mongolian divisions (a Chakhar (Inner Mongolian) Division of 180 men and two divisions of local Mongolians totalling 360 men), a four gun artillery section of 60 men, and a machine gun unit of 80 men with ten guns. Two anonymous Englishmen somehow found themselves in the Baron’s service. Smaller White Army units driven across the border by the Bolsheviks and camped around the country allied themselves to his command.

The Japanese soldiers served in the Division in a covert semi-official capacity. Japanese military command in Russia initially regarded the Baron as a geopolitical tool for the Far East; they soon discovered that, unlike Semenov, the Baron could not be bought. In leaving Siberia the Baron was not fleeing history. He was intent on making it.

The Assault

The Asiatic Cavalry Division came down from the hills and attacked the town at six o’clock on the morning of 1 February. The initial Chinese defences were ripped apart by the desperate assault. Before the battle the Baron, like a medieval lord, gave his men three days to loot and rape {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} as reward. The troops, who had spent months living in the desolate steppes of Mongolia, saw {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} as the last chance for food, warmth and shelter. The Asiatic Cavalry Division were gambling their lives on this final throw of the dice.

They broke the back of the Chinese lines and rampaged through the streets, hunting down fleeing defenders by the light of fires set by saboteurs. Hand grenades blasted out the doors and windows of buildings used as the last line of defense by Chinese soldiers. Cossacks galloped on horseback through the streets killing anyone in the open. There was constant rifle and artillery fire.

By the early morning of February 2nd hundreds of Chinese defenders were dead or trying to find an officer who would not kill them after they surrendered. Men of the Asiatic Cavalry Division not in the front line of the fighting turned on the liberated areas of the town. There was mass looting. Chinese civilians were murdered. Filthy lice carrying soldiers who had last changed their uniforms back in Russia broke into clothing shops and dressed in silks. Alcohol was discovered and drunken men staggered round {{Wiki:Ulan Bator|Urga}} firing into the air. A Cossack soldier was so drunk he turned his gun on his own unit, killing several, before he was shot dead.

Chinese banks were looted. Soldiers organized an ad hoc lottery: laughing men formed a line for one chance to plunge their hands into strong boxes. The lucky found gold coins or jewellery. Those with paper currency threw it into the streets.

‘The scene was worthy of a good painter,’ remembered Alioshin, ‘wild men, with fresh blood on their hands, clothing and boots, standing in line before the bank’s safes, awaiting their turn at the loot. The light from numerous fires made their faces bronze. It was remarkable that nobody paid any attention to their wounds…’.15

Pogrom

Real horror began when the Baron’s men freed Russian prisoners from the Chinese run jails. These men had been locked up in terrible conditions with little or no food several weeks before as revenge for local Mongolian forces joining the Baron. The plight of this group of men – which included many ex-Kolchak officers – was later given as a reason

for the urgency of the assault on Urga by the Baron’s adjutant Makiev. Old rivalries were forgotten. The freed men were shown the nature of the new order in Urga when one asked for a horse in case the Asiatic Cavalry Division had to retreat; he was shot dead. The rest joined drunken soldiers in a mob led by Dr Klingenberg – the Division’s doctor – and turned on the Jews.

Any Jewish men the mob found were killed by being hit in the face with wooden blocks until they died. Women were gang raped and killed; wives and daughters who offered themselves to save their men did not survive to see the agreement broken. Half-naked bodies lay in the streets and houses as the mob moved on. Alioshin saw a sympathetic officer beat them to the house of a young girl and offer her a straight edge razor; she gratefully cut her throat. Another officer who tried to rescue a woman being raped by a group of Cossacks at the Russo-Asiatic Trading Company was shot dead by them.

Olsen, a Danish citizen, who protested was roped to a horse and dragged through the streets until he died. Another foreigner Alioshin knew only as Olay was killed by Dr Klingenberg to get his medical supplies. Chinese resistance continued sporadically throughout February 2nd. There was a fierce but short-lived firefight between Ungern’s Cossacks and the Chinese near the

Russian cemetery in the foreign section of the town. Boris Volkov (1894-1954), a former intelligence officer for Kolchak who had earned himself a death sentence from Semenov by spying on him for the Admiral and was living in Urga after the White Army’s collapse, found himself in the middle of the battle:

‘Our house, the former consulate, was the first to be occupied by the Baron’s men. I will never forget those Cossacks in rags, half dead from the cold, who smashed the windows with their gun butts and burst into the house under the fire of Chinese artillery and rifles’.16

Small scale house to house fighting continued through the day as did mob violence directed against Chinese civilians. The Mongol troops allied with the Baron were the main protagonists in these attacks. Some Chinese were sheltered by Russians and other foreigners – a dangerous move. An American named Guppel who hid Jews and Chinese was forced to give them up by the mob or die. Even Tohtoho, a Mongolian prince, was besieged until he gave up those he had allowed into his home.

Chinese Collapse

By the morning of February 3rd the Chinese resistance was broken; eight carloads of Chinese officials fled Urga, abandoning their troops. Surviving units attempted to escape through the Chinese district of Maimaichen at the far east of the town. They were cut to pieces by enfiladed machine gun fire on a road by the Russian concession.

Those left broke out to the north and left Urga to the Baron. General Chu tried to marshal his troops from the snowbound gold mines of Dzumodo but the soldiers were out of control and could not be stopped; they looted Chinese farms as they fled towards the Russian border.

The Hungarian Joseph Galeta was at Chu’s makeshift headquarters in the aftermath of the breakout: ‘General Chu’s army, under the shock of their sudden defeat, had become a panic-stricken rabble and in their haste to get as far ahead of the pursuing army as possible they did not hesitate to rob their compatriots. While the farmers were crouching in the corners in fear of their lives, the soldiers shot their pigs and cattle, and breaking open the corn bins shovelled the corn in front of their horses’.17

A smaller group of 300 managed to escape to the south; they were hunted down and killed by Asiatic Cavalry Division’s troops near Chorin-Chure. Their unburied bones littered the area for years. Pershin, head of the Russo-Mongolian Commercial Bank, watched panicking soldiers flee past his house ‘without warm clothes, without shoes, without packs. The men, the horses, the carts were all mixed together. Among this rout one could occasionally pick out the carrying of weapons and provisions’.18

With the Chinese garrison gone or surrendered the town became calmer. There was still some looting against Chinese merchants. The majority of the violence had taken place in the Chinese sector against Chinese civilians, with forays into the foreign sector during the attacks on Jews.

Most of the Russian and religious areas of the town had only seen fighting against troops – both Volkov and Pershin (no friends of the Baron) in the heart of the Russian community would be unaware of the atrocities committed by the Baron’s soldiers

until after the battle. They were aware of Chinese atrocities. The few Chinese soldiers trapped in the town shot at any foreigner they saw before looting the homes of Russian civilians. As the Baron’s men closed in they abandoned their uniforms and tried to hide; sixty were found in a house in the Russian sector – all were executed.

The Baron’s Law

Baron von Ungern-Sternberg set up his command at the eastern end of Urga in Maimaichen on 3 February. He directed mopping up operations but was primarily interested in securing Chinese munitions – fifteen canon, four thousand automatic weapons, equipment, animal fodder and supplies – and the contents of the Maimaichen Chinese Bank and the Frontier Bank whose vaults were full of gold.19

Mongol troops and local inhabitants headed for the religious heart of the town, exhilarated by their victory and what they saw as the dawning of a new age for Mongolia. Buddhist services were held the evening of February 3rd. ‘After sunset one could hear giant sacred trumpets whose sound now brought pleasure instead of misery echoing in Da-Hure,’ wrote Pershin. ‘After two months of enforced silence the trilling of the bachkours returned with force through the icy air’.20

The Baron’s new order in Urga instituted the rule of law on February 4th. A fire caused by looters had begun in the town that evening, threatening armouries and the central religious district. The Baron rode in from Maimaichen to oversee the fire fighting efforts and the blaze was put out before nightfall.

On his way into central Urga to take command he saw two young Mongolian women carrying bundles of cloth stolen from a Chinese shop. He ordered them arrested and a week later they were wrapped in the stolen cloth and hanged outside the scene of the crime. It was the first public execution in Urga’s history. The three days of looting and rape were over.

In the aftermath of the fighting the Urga dogs roamed the streets of the Chinese district gnawing on the bodies of the dead. Volkov saw decapitated heads lying in the doorways of wrecked Chinese shops. Cossacks wearing outlandish silk coats over their ragged uniforms set up camp in abandoned buildings.

Military discipline was reimposed amongst the wreckage. The sadist Colonel Leonid Sipailov was made commandant of the town. Looting, murder and rape of civilians was punishable by death. For drunkenness the punishment was lashes with a split bamboo cane: twenty-five for civilians, fifty for privates, one hundred for officers.21 There were soon bodies hanging outside shops and buildings.

Soldiers were prepared to risk their lives for alcohol: Ossendowski heard that Sipailov arrested two Cossacks and a Mongol who had stolen brandy from a shop. He forced them to return the brandy and ordered the Mongol to hang the

Cossacks by the door of the shop; he then hanged the Mongol. The Chinese proprietor appealed to the Baron a few days later for permission to cut down the corpses as they were discouraging customers. Chinese civilians were ordered to bury the dead. Major Dockray, an Englishman resident in Urga, estimated there were 2,500 corpses.22

The mass killing began again on February 5th but this time as a legalized measure. The Baron ordered an official pogrom against the Jewish community from his Maimaichen headquarters. In contrast to the riotous mob violence of the battle this was to be a methodical military operation commanded by Sipailov. The Baron wanted all Jews in Urga dead.

In May 1921 he wrote about his anti-semitism to the White Russian General Moltchanov in Vladivostok: ‘I have always followed your activities and approved of your ideas on the terrible plague that is the Jews, these parasites who corrupt the world’. He had issued orders to his men to kill any Jews they found when the Division crossed the border into Mongolia.

Two of his officers had been captured by the Chinese in 1920 and were held in a Manchouli jail; they justified the robbery and murder of an entire Jewish family on the grounds they had written permission from the Baron. The order read: ‘Commissars, Communists and Jews, together with their families, shall be destroyed. Their entire property shall be confiscated’.23 Sipailov was to put the Baron’s beliefs into practice.

Despite this, the Baron’s anti-semitism - which often appeared monomaniacal - had unpredictable limits. His chief spy in Urga before the attack was a Jewish civilian called Jacobson and he utilised Jewish spies in China and elsewhere. When Cossacks invaded the compound of the American Trading Co.

and tried to rape the Jewish fiancée of an American called McLoughlin the Baron’s guard intervened and brought everyone to his Maimaichen headquarters. After McLoughlin explained the situation the Baron scribbled out a passport for the girl on a scrap of paper and had the Cossacks shot.24 A mental aberration? Political pragmatism? The Baron later tried to win recognition for his Mongolian state from the Americans. No other Jews were that lucky.

The Jews in the town did not have a separate district of the Foreign Sector (as did the Tibetans) but lived scattered amongst the Russians. The mob had already attacked the obvious targets and with most Jewish people in hiding – either hoping they would not be discovered in their own homes or staying with others prepared to risk their lives – the pogrom faltered. Pershin estimated that fifty Jews in total were killed by Sipailov’s troops over the course of the occupation. Pershin himself hid a dentist called Gauer and his family amongst the crowd of Russian exiles living in his substantial house.

The Jews of Urga were helped by the fact that the Mongols were unable to understand the Baron’s anti-semitism: to them all Europeans were the same and they could not understand how one group (hara oros – dark Russians) could be as evil as the other group (tsagan oros – blond Russians) claimed. The explanation that all Jews were Communists was too thin to explain the systematic executions. Thanks to the support of Mongolians and the Russian exile community most Jews escaped the pogrom.

A group of Jews hid at the home of Togtokhogun, a Mongolian prince, warrior and national hero. He protected them and others in danger from the Baron’s men. The Chinese Doctor Li – well known in Urga for owning one of its few automobiles – was planning to escape over the Chinese border with his beloved three-year-old daughter, who was dying of typhoid. He offered to take letters from the Jews hidden by Togtokhogun to their friends and family in Manchuria. The plan was betrayed and Li captured by Sipailov.

When his men searched Li’s house they discovered his daughter had died during the preparation for the escape; the grieving Li had embalmed her. Cossacks found her body in the bathtub. Faced with losing what was left of his daughter Li broke down and betrayed Togtokhogun. When Sipailov went to see him the prince refused to hand his guests over and left the Russians reduced to impotent surveillance of the house.

There were still deaths. When Cossacks slaughtered a Jewish family the Mongolian nanny fled with the baby and had it baptised a Christian by an Orthodox priest at the Russian consulate; the pursuing Cossacks were forced to accept the conversion by the priest but turned on the nanny and slashed her to pieces with their sabres. Despite approaches from Lamas, the Russian community and representatives of the Living Buddha the legalised anti-semitic executions continued through the Baron’s rule of Urga.

Ossendowski – an admirer of the von Ungern-Sternberg who later became his political advisor - blamed Colonel Sipailov for the atrocities attributed to the Baron. Alioshin, who had stood in line for the Baron’s inspection with other new recruits and conscripts before the battle, thought the Baron responsible for enough atrocities on his own.

[The Baron] made the inspection personally. He would stop at each man separately, look straight into his face, hold that gaze for a few moments, and then bark: "To the army"; "Back to the cattle"; "Liquidate". All men with physical defects were shot until only the able-bodied remained. He killed all Jews, regardless of age, sex or ability. Hundreds of innocent people had been “liquidated” by the time the inspection was closed.25

Despite the cruelty, the relationship between the Mongolians and the Baron was initially excellent. They were confused rather than horrified by the harshness of his rule. He was still their god of war; he had delivered the Bogdo Geghen from the Chinese. They saw the common Buddhist faith and his symbolic part in their mythology. The Baron saw them as the vehicle for his destiny.

The Baron’s Headquarters

On February 6th Pershin was approached by the Russian community and asked to make an official visit to the Baron. He was accompanied by Solimanov, a merchant who represented the Muslim community of the town. The streets of Urga were deserted but the district of Maimaichen was full of military activity. Pershin noted the Baron’s men were ‘a mixture of all tribes and races, from the Russians of Europe and Siberia, to Mongols, Buriats, Tartars, Kirghizes …' 26

The Baron – indifferent as always to physical comfort - had set up headquarters in the looted shell of a Chinese house. The broken windows were pasted over with paper and the house was cold despite a smoking stove. Lamas, Mongol princes and Russian officers waited in the reception room. The two other rooms in the house were sparsely furnished and dirty; in one,

Colonel Ivanovski sat on stool eating noodles and trying to ignore the pain of an abscess in his tooth. Pershin later discovered that, despite his proximity to the Baron, Ivanovski helped many people to escape Urga – for a fee. The Baron occupied the room at the back; it was minimally furnished with a table, chair and bed.27

Baron von Ungern-Sternberg acknowledged their presence with a curt nod. Pershin was impressed, despite himself, with the Baron’s aristocratic bearing. With a shave and a haircut the Baron could have fitted into a high society gathering.

The first item on Pershin’s agenda – a cautious plea for tolerance towards the Jewish community – was angrily dismissed before he got very far. Tolerance was a sign of decadence to the Baron.

The main reason for Pershin and Solimanov’s visit was to request permission to form a self-defence force to protect the town from looters. The Baron refused. He told them he had ordered an end to looting and appointed Sipailov town commandant. He had no interest in creating a new armed force in the town that was not under his direct command. The interview was over.

Throughout February the Baron’s power base in Mongolia expanded. The few pockets of Chinese resistance in Kobdo, Uliassutai and Wang Kuren were taken by the allied White Army units of Colonels Kazantzev and Kazagrandi loyal to the Bogdo Geghen’s government. Much of Mongolia was ungovernable due to its remoteness but the Mongolian people relished their new independence and supported the regime. Life in Urga achieved a new authoritarian order.

The markets restarted on the streets; shops opened; Sipailov and his Cossacks continued to hunt down Jews; men and women were hanged for theft; defences were rebuilt; attempts made to clean up battle damage; Mongolians attended their newly opened temples; a military bureaucracy created to run alongside the civil Mongolian one; new jails and torture houses were opened;

Chinese officer prisoners executed and their men forced into the Baron’s service; the Baron moved his headquarters into central Urga; new paper currency was introduced; and, most importantly, preparations were made for the coronation of the Bogdo Geghen – the Living Buddha – as Emperor.

Coronation of the Living Buddha

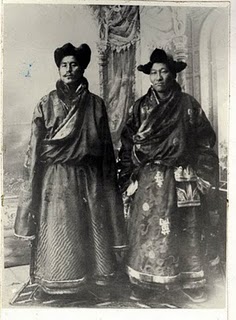

The coronation took place on February 26th. The Bogdo Geghen was fifty-one when he was crowned Emperor of Mongolia. He was the eighth reincarnation of the Buddha and had been brought to Urga as a five-year-old. As the Living Buddha the lamas were unable to refuse him anything and he led a dissolute early life. Alioshin heard that ‘he liked to hunt down his people with bloodhounds or to smash the crowd of worshippers by madly galloping on a horse into their midst. Later he became a drunkard and quite easy with women, in consequence of which he contracted disease and lost his sight’.28

Some of his exploits were simply childish: he hung a wire connected to a strong battery over the wall of a temple; passers-by grasping the wire got an electric shock they were supposed to attribute to the Living Buddha’s magical powers.

His other activities were less childlike. The walls of a room in his Winter Palace at Urga were covered with long mirrors; the mirrors turned on hinges to reveal pornographic drawings on the stone behind. He had lovers of both sexes, stole his wife from a well known wrestler, allowed her to be fondled by members of his court and had a long relationship with his male attendant Legtseg. He and Legtseg

swapped clothes and identities for sexual roleplays. It became so intense that even the Living Buddha’s louche court were disturbed by the adjutant’s influence. Legtseg, believing the relationship was ending and hysterical, attacked the Living Buddha and was arrested; the Living Buddha used his influence to have him exiled to a remote

part of Mongolia. A local prince loyal to the Buddhist hierarchy murdered him by burying him alive.29 The Living Buddha went blind through undiagnosed syphilis. His dissolute lifestyle slowed but he still drank; there were crates of Russian champagne in his cellars. He was a friend of Russia and a passionate believer in Mongolian independence.

Alioshin, as part of the Baron’s army, spent the day of his coronation as one of many lining the route to the Maidari temple as honour guard. After hours of boredom waiting in the cold the Bogdo Geghen passed by in a palanquin (a covered litter) carried by eight men. The honour guard were not allowed into the temple for the ceremony and Alioshin’s chief memory was being disappointed with the food at the feast afterwards.30

Makiev, the Baron’s adjutant, left a more detailed description. Mongolians from all over the country came to Urga from the occasion; they picked their way through the devastation of battle remains on their way to the temple. The Urga dogs were overworked. Decaying bodies still lay in the streets and the Mongols were shocked at the evidence of massacres.

The honour guard received new uniforms before the ceremony: Mongolian coats (tyrlyks), silk caps and hoods which attached to the caps (bachlits). The bachlits were coloured green for the Tartar units, yellow for the Tibetan and red for the Headquarters guard. The Baron himself wore a silk Mongolian robe with general’s epaulettes

and his cross of St George medal at the breast. The procession through the streets began at ten in the morning. The honour guard kept back the crowds as a huge cavalcade of lamas, Mongol princes and a select marching group of the Baron’s men led by Colonel Rezukhin, commander of the Buriat detachment, passed through the streets behind mounted heralds. The heralds carried a Mongolian flag, embroidered in gold with a soiombo, an ancient Mongolian symbol now used to represent

independence. Behind them was the Living Buddha’s personal guard wearing red tyrlyks and yellow armbands with the black Asiatic sign of the swastika. Then came the Bogdo Geghen and, behind him, the Baron riding a white horse with yellow reins. As the Living Buddha passed by, blind eyes behind dark glasses, the crowds knelt on the ground.31

Cossacks presented arms and the parties entered the temple to the sound of Mongolian trumpets. The coronation took place with solemn ceremony. Afterwards the Baron gave a speech. Describing himself as a Mongol auxiliary he began by talking about Mongolia’s glorious history under Genghis Khan and called for a renaissance.

Next he began a violent attack on Communism, driven by his personal synthesis of apocalyptic [[Wikipedia:Christianity|Christianity]] and warrior Buddhism. Finally he ‘launched a fantastic appeal, full of quotations from the Apocalypse and the Lamaist scriptures, for a punitive expedition against the Red Russians’.32

Tidemark

That morning was the high point of the Baron’s life. For the first time in three hundred years Mongolia was an independent nation. He had created a Buddhist state and enthroned an Emperor. The touchstone of Ghengis Khan’s Mongolian Empire had been resurrected. Mongolia could now be cleansed of Chinese, Jews and Communists. Russia would follow.

What appears to history as the moment the wave broke and began to fall back, was to the Baron and his officers on the ground in Urga just the first step in a greater plan.

Notes

General Mongolian history can be found in the early chapters of Bawden's 'Modern History Of Mongolia' (1988).

1. Alioshin, ‘Asian Odyssey’ (1941) p256

2. Youzefovitch, 'Le Baron Ungern: Khan des Steppes' (2001) p51

3. Alioshin, op cit p241

4. Ossendowski, ‘Beasts, Men And Gods’ (1922) chXXXV

5. Ossendowski, op cit chXXVII and XXXII

6. Ossendowski, op cit chXXXV

7. Alioshin, op cit p242 and Haslund, ‘Tents In Mongolia’ (1934) p69

8. Youzefovitch, op cit p111

9. Tang, ‘Russian And Soviet Policy In Manchuria And Outer Mongolia’ (1959) p369

10. Galeta, ‘The New Mongolia’ (1936) p146

11. Ossendowski, op cit chXXXIII

12. Alioshin, op cit p227

13. Ossendowski, op cit chXXXIII

14. Alioshin, op cit p227

15. Alioshin, op cit p236

16. Volkov, ‘Oberst Ungern’, B N Volkov Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

17. Galeta, op cit p154

18. Pershin, ‘Baron Ungern, Urga i Altan Bulak’, D Pershin Papers, Hoover Institution Archives

19. Youzefovitch, op cit p149

20. Pershin, op cit

21. Alioshin, op cit p237

22. North China Herald, 26 March 1921

23. Ed. Wieczynski, ‘Modern Encyclopedia Of Russian And Soviet History’ p205

24. North China Herald, 16 April 1921

25. Alioshin, op cit p238

26. Pershin, op cit

27. Youzefovitch, op cit p160

28. Alioshin, op cit p244

29. Bawden, ‘Modern History Of Mongolia’ (1988) p166

30. Alioshin, opcit p245

31. Youzefovitch, op cit 169-176

32. Tang, op cit p369

Further Reading:

There was a point in about 2005 when half the writers in London and even more elsewhere were planning to write a biography of Baron von Ungern-Sternberg. At the only literary party I ever attended (a godawful boring launch for an agent's website) I met two of them inside ten minutes. I kept quiet about a one time ambition to write the same book myself.

The above piece was originally done as a sample for potential publishers in '03. Some interest, nothing concrete, and I wrote ‘Franco’s International Brigades: Foreign Volunteers and Fascist Dictators in the Spanish Civil War’ instead.

The Baron was never the easiest subject. His earliest would-be biographer Vladmir Pozsner gave up after hearing so many conflicting stories from exiles in interwar Paris that his head was ringing and wrote a novel instead. It would become a common reaction to the Baron’s short sharp life.

The exotic nature of his Eurasian adventures coupled with the lack of any corroborating detail meant the Baron has more of a life in fiction than he did in biography. A German Third Reich author called Berndt Krauthof wrote a novel about Ungern in 1938 called 'Ich befehle'. In 1973 Jean Mabire, a right-wing French writer better known for his histories of the Waffen-SS, published a fictional account of the Baron’s life: 'Ungern – Le Baron Fou' (later republished as 'Ungern - Dieu De La Guerre'). Mabire garnished it with photographs, footnotes and appendices.

The Baron appeared waving a sabre in the sharply drawn panels of the Italian graphic novel 'Corto Maltese in Siberia' by Hugo Pratt. The Russian writer Victor Pelevin, whose novels were damned as a computer virus eating away at cultural memory by a critic, gave the Baron a walk-on as the God of War ruling a metaphysical Valhalla in his druggy 1996 novel 'The Clay Machine Gun'.

When the Baron appeared in factual works on the Russian Civil War he received only a footnote or brief paragraph. To Peter Fleming, writing in the 1960s, he was a ‘moody swashbuckler with red hair and a pale face [who] was to gain a reputation for sadistic brutality which was surpassed by very few contestants on either side in the Civil War’.

In Richard Luckett’s later view of the White Armies, ‘Ungern-Sternberg, generally known as the Bloody Baron, looked totally ineffective but was, it seemed, more or less physically indestructible. He was also exceedingly cruel, and a sabre blow received during a trivial quarrel with a fellow officer may have mentally unbalanced him. The Baron, with his pale face, red hair, and long cavalry moustache, was soon one of the most feared men in Siberia’.

For a while the longest non-fiction account in English was to be found in Peter Hopkirk’s 'Setting the East Ablaze: Lenin's Dream of an Empire in Asia', a history of the Bolshevik Revolution in the Russian Far East, where the Baron takes his place amongst other such larger than life characters as Enver Pasha, the Turkish empire builder and General Ma, the sadist Chinese warlord fighting a jihad against the Red Army. The book

printed one of the few photographs believed to exist of the Baron: an iconic shot taken in Mongolia 1921 of von Ungern-Sternberg in ceremonial dress for the coronation of the Living Buddha, his piercing stare burning into the camera lens. (Who took it? Did he live?). Hopkirk’s version of the Baron’s life owes a lot to the novel Pozner wrote after abandoning his own biography.

There was even a children’s book about him - 'The Bloody Baron: Wicked Dictator Of The East': ‘The Baron himself had also lots of practice at killing people during his military career and was very good at it …The Reds hated people like the Baron who lived in big houses and treated the Russian peasants badly’.

The rediscovery of the Baron began in the country that had once hated him the most. Today the Baron is a cult figure for young Russians. The fall of Russian Communism in 1990 freed historians from writing state approved propaganda and allowed them to investigate previously forbidden subjects.

Leonid Youzefovitch wrote a book on the Baron in Russian, translated into French in 2001 as 'Baron Ungern: Khan des Steppes', which utilised previously unavailable Soviet sources and some forgotten memoirs by members of the Asiatic Cavalry Division. Only the 1941 'Asian Odyssey' by Dimitri Alioshin (probably a psuedonym) is available in English. Others have followed in Youzefovitch's footsteps but unless you read Russian you are out of luck.

In 2008 James Palmer wrote the first full English language biography of the elusive Ungern-Sternberg. It came out of nowhere and ruined the plans of many of those London writers I was talking about but it is a good, full book. If you enjoyed my piece and want to know more about the crazed White Russian ruler of Mongolia then Palmer's 'The Bloody White Baron' is the place to go next.