Vultures and charnel grounds – East and West

OK, I know this post is has little to do with developments in Buddhism here in the UK (pigeons are no match for vultures as a native avian species and our “health and safety gone mad” culture would present some pretty major obstacles). Nonetheless the subject is fascinating – let’s call it a meditation on impermanence… The incredible photographs are by Bo Løvschall and were originally posted here.

On the Tibetan plateau firewood is scarce and the ground is often frozen, too hard to dig a grave, so the Tibetans have traditionally used the funerary practice of “sky burial” in which the body of the deceased is offered to vultures. After days of making prayers and invoking the Buddhas’ blessings, the body is taken to a mountainside sky burial site and unwrapped.

In Tibet the practice is known as jhator, which literally means, “scattering to the birds.” The species of vulture involved is apparently the “Eurasian Griffon” or “Old World Vulture,” Order Falconiformes, Family Accipitridae, scientific name Gyps fulvus.

Vultures arrive and wait patiently, while the naked body is neatly sliced apart by the rogyapa (“body-breaker”).

As soon as he stands away from the body, the birds start to dine furiously on it. With fierce fighting and great speed the vultures strip the flesh from the bones, while pieces of human flesh fly everywhere.

Dissection occurs according to instructions given by a lama or tantric practitioner. These customs were first recorded in the treatise Liberation Through Hearing During The Intermediate State (Tib. bardo thodol) known colloquially as the Book of the Dead, composed in the 8th century by Padmasambhava, written down by his student, Yeshe Tsogyal, buried and subsequently discovered by the terton, Karma Lingpa in the 12th century.

Sky burial may initially appear grotesque for Westerners, but for Tibetans, it is a template for teaching on impermanence.

Jhator is considered an act of generosity on the part of the deceased, since the deceased and his/her surviving relatives are providing food to sustain living beings. Some consider the vultures to be emanations of Bodhisattvas.

The procedure takes place on a large flat rock long used for the purpose. The charnel ground is always higher than its surroundings. It may be very simple, consisting only of the flat rock, or it may be more elaborate, incorporating temples and stupas.

The jhator usually takes place at dawn. The full procedure is elaborate and expensive. Those who cannot afford it simply place their deceased on a high rock where the body decomposes or is eaten by birds and animals.

After the body is stripped of flesh, the bones and skull are broken up with sledgehammers, crushed and mixed with barley flour by the rogyapa. Many rogyapas first feed the bones and cartilage to the vultures, keeping the best flesh until last.

In places where there are several jhator offerings each day, the birds sometimes have to be coaxed to eat, which is accomplished by a ritual dance. It is considered a bad omen if the vultures will not eat, or if even a small portion of the body is left after the birds fly away.

In places where fewer bodies are processed, the vultures were more eager and sometimes had to be fended off with sticks during the initial preparations.

The final part of the ritual is to burn the remaining items.

The location of the sky burial preparation and place of execution are understood in the Vajrayana traditions as charnel grounds (Tib. durtrö). Charnel Grounds feature in Indian Buddhist history and iconography as cemeteries where bodies are deposited. Unlike crypts or vaults, these areas are above-ground sites for the putrefaction of bodies, generally human, where formerly living tissue was left to decompose uncovered.

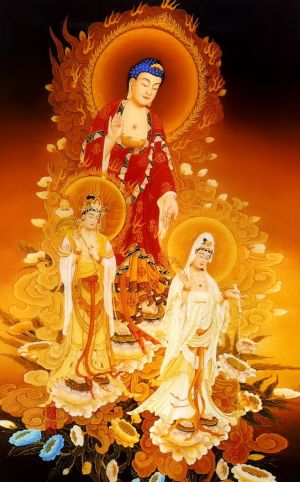

The Buddhist tantras that describe wrathful deities also describe wrathful venues for their practice. Charnel grounds were the most fearsome and abhorrent places in India. Wrathful deities are therefore associated with charnel grounds and peaceful deities are associated with pleasant and beautiful surroundings.

According to the descriptions of wrathful deities and their environments, the eight charnel grounds surround the central palace and deity. These charnel grounds also have physical locations in India such as the “Laughing” charnel ground at Bodhgaya and the “Cool Grove” charnel ground close by, along with the “Frightening” charnel ground in the Black Hills of Bihar. There are variations in the names and descriptions of the different charnel grounds, as well as different translations. They all an indication of the nature of these places:

According to Konchog Lhundrub‘s teachings on the Hevajra Tantra, in the east is the “Gruesome” charnel ground (chandograkatasi); in the south “Frightful with Skulls” (bhairavakapalika); in the west “Adorned with a Blazing Garland” (jvalamalalankara); in the north “Dense Jungle” (girigahvaronnati); the north-east “Fiercely Resounding”

(ugropanyasa); th south-east “Forest of the Lord” (ishvaravana); the south-west “Dark and Terrible” (bhairavandhakara); and the north-west “Resounding with the Cries Kili Kili” (Kilikilaghoshanadita). “Furthermore, there are headless corpses, hanging corpses, lying corpses, stake-impaled corpses, heads, skeletons, jackals, crows, owls, vultures, and

zombies making the sound, “phaim”. There are also siddhas with clear understanding, yaksha, raksha, preta, flesh eaters, lunatics, bhairava, daka, dakini, ponds, fires, stupa, and sadhaka. All of these fill the charnel grounds.”

A ritual text composed by Chogyal Phagpa based on the Chakrasamvara Tantra lists them as: in the east “Gruesome”; in the south “Terrifying”; in the west “Blazing with [the Sound] Ur Ur”; in the north “Dense Wild Thicket”; the north-east “Wildly Laughing”; the south-east “Marvelous Forest”; the south-west “Interminably Gloomy”; and the north-west “Resounding with the Sound Kili Kili”.

According to Dudjom Rinpoche in The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism: its Fundamentals and History (1991), the names of the Eight Great Charnel Grounds are: “The Most Fierce”; “Dense Thicket”; “Dense Blaze”; “Endowed with Skeletons”;

“Cool Forest” or “Cool Grove”; “Black Darkness”; “Resonant with ‘Kilikili'”; “Wild Cries of ‘Ha-ha'”. The symbolism of the charnel ground is highly significant. It represents the death of ego, and the end of attachment to this body and life, craving for a body and life in the future, fear of death and aversion to the decay of impermanence.

According to Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche in the Longchen Nyingtik Practice Manual:

Right now, our minds are very fickle. Sometimes you like a certain place, and it inspires, and yet with that same place, if you stay too long, it bores you. […] As you practise more and more, one day this kind of habit, this fickle

mind will just go. Then you will search for the bindu interpretation of the right place, and according to the classic tantric texts, that is usually what they call the “eight great charnel grounds”. So then, you have to go to a cemetery, especially to one of the eight cemeteries. There, under a tree, in the charnel ground, wearing a tiger skin skirt,

holding a kapāla and having this indifference between relatives and enemies, indifference between food and shit, you will practise. Then your bindu will flow. At that time, you will know how to have intercourse between emptiness and appearance.

In Dakini’s warm breath: the feminine principle in Tibetan Buddhism (2001) Judith Simmer-Brown conveys how the ‘charnel ground’ experience may present itself in the modern Western mindstream situations of emotional intensity, protracted peak performance, marginalization and extreme desperation:

In contemporary Western society, the charnel ground might be a prison, a homeless shelter, the welfare roll, or a factory assembly line.

The key to its successful support of practice is its desperate, hopeless, or terrifying quality. For that matter, there are environments that appear prosperous and privileged to others but are charnel grounds for their inhabitants–Hollywood, Madison Avenue, Wall Street, Washington, D.C.

These are worlds in which extreme competitiveness, speed, and power rule, and the actors in their dramas experience intense emotion, ambition, and fear. The intensity of their dynamics makes all of these situations ripe for the Vajrayana practice of the charnel ground.