Who’s who in the chants

I. Cast of characters.

The Buddhas:

The Bodhisattvas:

Manjusri Samantabhadra Avalokitesvara Ksitigarbha

These are the main personages who appear in our chants. Note that, with the exception of two stanzas in the Morning Bell Chant (the first two four-line stanzas which end in “namu Amita Bul”) these chants are not particularly Zen chants, but belong to the broader Mahayana liturgy. Thus this discussion necessarily focuses on the broader Mahayana tradition.

II. The buddhas

There are many many buddhas in the Mahayana pantheon. We will only talk about the three who appear in our chants, but two others worth knowing about are Maitreya, the buddha of the future, and Baisajyaguru, the medicine buddha. The famous Korean buddha statue in which the buddha sits on a chair with one foot resting on the other knee is Maitreya; and any depiction of a buddha in which the buddha is sitting and holding a flask on his lap is Baisajyaguru.1

1 Unless it is Avalokitesvara, who is a bodhisattva not a buddha; Baisajyaguru’s flask is round and Avalokitesvara’s is long.

II.1. Vairocana

Vairocana is the mystical celestial buddha, co-terminal with the universe, i.e., the universe is, in some sense, the body of Vairocana Buddha. At the boundaries Vairocana morphs into both Amida Buddha and Shakyamuni Buddha.

Vairocana presides over the Avatamsaka Sutra (the long, complex, mystical sutra which provides the basis for Hua Yen Buddhism),2 although he does not speak in it, and opens the Brahma Net Sutra (the basis for the 64 lay/bodhisattva precepts).3 To quote briefly from Thomas Cleary’s translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra:

“The Buddha body extends throughout all the great assemblies: It fills the cosmos, without end. Quiescent, without essence, it cannot be grasped; It appears just to save all beings…

“The Buddha’s body of pure subtle form Is manifest everywhere and has no compare; This body has no essence and no resting place: It is contemplated by Skillful Meditation…4”

To quote briefly from the opening of the Brahma Net Sutra (translated by the Sutra Translation Committee of the United States and Canada):

“Now, I, Vairocana Buddha am sitting atop a lotus pedestal; On a thousand flowers surrounding me are a thousand Sakyamuni Buddhas.

2 Invoking the beings who were present as the Avatamsaka Sutra was originally spoken is said to have powerful effects. There is a Hwa Om Song Jong chant (Hwa Om is the Sino-Korean pronunciation of Hua Yen; Song Jong here means sangha). Paintings portraying these beings are supposed to go above side altars. Not having a side altar, Kansas Zen Center among others has a calligraphy invoking these beings.

3 Which is itself an extract from the Longer Sukhavativyuha Sutra.

4 Cleary translates names of bodhisattvas, so Skillful Meditation is a bodhisattva, not a virtue. Other translators have adopted this format.

“Each flower supports a hundred million worlds; in each world a Sakyamuni Buddha appears. All are seated beneath a Bodhi-tree, all simultaneously attain Buddhahood.

All these innumerable Buddhas have Vairocana as their original body…”

Vairocana appears in our chants in the beginning of the morning bell chant, where he is called Biro. In Zen Master Hae Kwang’s interlinear translation:

Namu Biro gyo ju hwa jang ja jon (Homage to Vairocana, teaching master, flower womb love lord) yon bo gye ji gum mun (expound treasure poem of golden text) po nang ham ji ok chuk (open carnelian case of jade scroll) jin jin hon ip (dust dust mix enter) chal chal wol lyung (moment moment completely fuse)

Later he briefly appears again:

Pyong dung sana mu ha cho (Equal rank, Vairocana has no fixed place)

In the morning bell chant the “treasure poem… jade scroll” is the Avatamsaka Sutra. The lines “jin jin hon ip chal chal wol lyung” present a simultaneous vision of

(i) emptiness/interpenetration;

(ii) creation;

(iii) identification of the universe with the body of Vairocana.

“Pyong dung sana mu ha cho” is a vision of the essential equality of all things, and Vairocana’s interprenetration (“no fixed home”) of them.

In all of these texts the vision of Vairocana is the Mahayana vision at its most mystical. Vairocana’s body is the universe. Vairocana is the generator of the universe. Manifesting everywhere, he is completely empty. Perfectly still, he never rests. He is the original body of all buddhas. He is the generator

of all buddhas. It is through Vairocana that beings attain Buddhahood. No wonder the 16th century Jesuit missionary to Japan, Frances Xavier, translated “God” as “Vairocana”, and thus easily gained converts from the Shingon school, one of many Buddhist schools — Hua Yen and

Vajrayana are two others — in which Vairocana is a, and for the Hua Yen, arguably the, major figure.5

Aside from invoking the doctrines associated with Vairocana, the Avatamsaka Sutra itself appears within the Morning Bell Chant in the lines:

Yag in yong nyo ji (If one wants fully understand) Sam se il che bul (three worlds all Buddhas) Um gwang bop kye song (should view dharma world nature) Il che yu shim jo (all only mind make).6

II.2. Amitabha

Amita Bul, or Amida Buddha, or Amitabha, is the Budda of the western pure land or realm. Pure lands are not located in our space-time. For example, the western pure land is not west of China or India, it is west of our entire universe. Each pure land/realm is a world/universe/realm presided over by a major

figure — buddhas, bodhisattvas, even leading disciples such as Shariputra or Mahakasyapa. These pure lands interact with each other and with our world, exist within and apart from time (kalpas) and can even simultaneously occupy the same space and time. With the exception of Amitabha’s realm, the beings living in pure lands have already attained enlightenment.

Unlike Vairocana, Amitabha has a back-story. He was, as Wikipedia charmingly puts it, “in very ancient times and possible in another system of worlds” a monk, maybe a king who became a monk, who lived in the time of the Buddha Lokesvararaja. Realizing that pure lands are closed to those who most need them,

he resolved to have a pure land in which all beings could, by sincere practice, be reborn, and took 48 vows to commit himself to this — these vows, found in the Brahma Net Sutra, are the origin of our bodhisattva teacher vows.

And why would you want to be reborn in Amitabha’s western pure land? Because in that realm there is no hindrance to practice — all beings focus on becoming and eventually become bodhisattvas or

5 Hua Yen is the Chinese translation of Avatamsaka; it means Flower Adornment. 6 In a slightly different translation, these lines can be found in Cleary’s translation, p. 452. The three worlds are either the worlds of past/present/future or the worlds of desire/form/formlessness.

buddhas, returning to other realms to help others attain buddhahood. And so the cycle is broken even as it continues: rebirth in the pure land; eventual bodhisattva- or buddhahood; rebirth in other realms to help others be reborn in the pure land…

The two sutras with which Amitabha is most associated are the Sukhavativyuha Sutra (a.k.a. Infinite Life Sutra) — actually, there are two of these, the longer and shorter version — and the Amitabhavyuha Sutra. These are important in Pure Land Buddhism, but except for the extract of the Longer Sukhavativyuha Sutra known as the Brahma Net Sutra, these are not important outside of Pure Land Buddhism. They focus on Amitabha’s life (beginning with the back story when he was the monk Dharmakara), what the western pure land is like, and how to get there. The most well known of Amitabha’s vows is that he will ensure rebirth in the western pure land for anyone who sincerely chants his name 10 times.

The first appearance of Amitabha in the morning bell chant is:

“Won a jin saeng mu byol lyom (Vow I exhaust life no other thought) Amita bul dok sang su (Amita Buddha uniquely marked follow) Shim shim sang gye ok ho gwang (Mind mind always joins jade curl light) Yom nyom mul li gum saek sang” (thought-moment thought-moment not leave golden form marked)

In these lines we see the notion of the special marks by which we can recognize a buddha (more of this later). More important is our own vow to follow Amitabha’s vows, his strong direction to save all beings, the natural consequence of the joining of mind, light, and wisdom.

“Amitabha” means “infinite light,”7 and in this aspect he takes on the mystical flavor of Vairocana. So, two lines after his introduction, right after “pyong dung sana mu ha cho” (equal rank, Vairocana has no fixed place) we chant “gwan gu so bang Amita” (perceive pray west realm Amida) — the second appearance of Amitabha in the chant.

After which there are fifteen repetitions of “namu Amita bul” — the Japanese call this the nembutsu. — homage to Amitabha! In Chinese it is: namo Amitofo; in Japanese, namu Amida butsu. Recall that a mere ten sincere repetitions will inspire Amitabha to ensure you are be reborn in the western pure land; we do fifteen in every early morning

7 The etymology is: amitabha: no-measure-light (“bha” is cognate with the “pho” in “photon”).

practice.8 Chanting the nembutsu is the main practice of the Pure Land school, which in its many incarnations is by far the largest Buddhist school in Asia.

Just before the final series of repetitions of the nembutsu we have a long passage invoking Amitabha which both refers to the special marks of the Buddha and Amitabha’s special vows:

“Bul shin jang kwan (Buddha body long wide) sang ho mu byon gum saek kwang myong (face good no limit gold color shine bright) byon jo bop gye (everywhere illumine dharma world) sa ship par won do tal jung saeng (48 vows free save many beings).”

There is a historical tension between Ch’an schools (including Korean Soen and Japanese Zen) and Pure Land schools. In Chinese Ch’an there is some syncretism. In Korean Soen, facing political threats from China and Japan, and centuries of Confucian repression, the major figures Wonhyo, Chinul and So Sahn encouraged unity, but despite the syncretism which distinguishes Korean Buddhism, the tension remained. In Japan — where, outside the Obaku school, Buddhism tended to be anti-syncretic —the split was pretty much complete.

The main charges against the Pure Land school are: the practice is too simple; it is not a serious practice; it is too focused on one’s own life and rebirth. When Zen Master Seung Sahn first came to this country, some people whose expectations were shaped by Japanese tradition claimed that we could not truly be a Ch’an, much less Linchi, school, since we incorporated repetitions of the nembutsu in our chants.

In response to these historic schisms, major figures such as the Korean master So Sahn and the Japanese master Hakuin bent over backwards to say that correct chanting of the nembutsu can indeed lead to enlightenment, or that correct meditation practice can indeed lead to the western pure land.

8 There is also a special Amita Bul chant which can be chanted when someone dies who has expressed a wish to be reborn in the western pure land. 9 Note from the Old Days: Back in the 1970’s the Providence Zen Center was at 48 Hope Street, and “48 vows” was translated as “48 hopes”.

Some Pure Land sects are what Zen Master Seung Sahn called “object religions” — you believe in Amitabha Buddha as a being who will save you, and you recite the nembutsu as a way of demonstrating your faith. But other Pure Land sects emphasize the nembutsu as a practice that brings clarity and through which one

can oneself attain enlightenment. From this standpoint, reciting the nembutsu is taking on Amitabha’s vows to awaken all beings. Thus, Shin Buddhism’s website speaks of “learn[ing] to embody the nembutsu for the sake of all beings.10

II.3. Shakyamuni Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama Shakyamuni is the historical Buddha: he was born a prince, lived in great privilege, escaped his privileged life, after long and hard practice became awakened (which is what “buddha” means), and spent the rest of his life teaching others. We’re not going to focus on these quasi-historical aspects of the historical buddha, but instead on the more fantastical Mahayana aspects that appear in the chants and at least some of the sutras.

In our tradition, Shakyamuni gets his own chant, Sogamuni Bul (Sogamuni is the Korean pronunciation of Shakyamuni), which we chant when we celebrate his birth or his enlightenment. He also appears in the Homage to the Three Jewels as the first jewel, and in the group chorus after a teacher chants the 10

great vows in Korean (which very few if any do, but Zen Master Seung Sahn did it every morning). He appears in nearly every sutra. At times (the Diamond Sutra, the Vimalakirti Sutra) he is a teacher, without emphasis on miraculous powers or a fantastical back-story. At other times he takes his place in the Mahayana pantheon, as ornate as any other Buddha. For example, here he is in the Brahma Net Sutra: “I have come to this world eight thousand times. Based

in this Saha World, seated upon the Jeweled Diamond Seat in Bodhgaya and all the way up to the palace of the Brahma King… Thereafter, I descended from the Brahma King’s palace to Jambudvipa, the Human World…” And recall, in the Brahma Net Sutra how each one of a thousand flowers has on it 100 million worlds, each of which has in it its own Shakyamuni Buddha, all of whom simultaneously attain enlightenment.

This magical Buddha is known by the 32 major and 80 minor attributes. You can Google them yourself, but they include such normal (if you’re a movie star) attributes as soft, smooth skin and an upright body, poetic qualities such as thighs like a royal stag and lion-shaped body (whatever that means), and such strange things as thousand-spoked wheel mark on each foot, webbed toes and fingers, and golden-hued body.

Recall the section of the morning bell chant quoted above with Buddha’s long, wide body? Yes, that is Amitabha, not Shakyamuni, but a few lines later we are reminded that the 360,000,119,500 names

10 Shin Buddhism, a branch of Pure Land, is a lay school and claims to be the largest sect of Buddhism.

of the Buddha are all the same name (a few stanzas earlier it was only 36,000,119,500 names, but who’s counting). The 32 major and 80 minor attributes apply to all Buddhas. But was the historic Shakyamuni supposed to have had webbed toes and fingers? Did people believe that baby Siddhartha was born with thighs like a royal stag and a thousand-spoked wheel mark on each foot?

Fear not, reality-based people. These characteristics belong not to the physical or emanation body (nirmanakaya) but to the reward body (sambhogakaya). There is also the dharmakaya (truth body). These are the three bodies of all Buddhas. One way to think of these bodies (rest assured that there are many

other ways of thinking about them) is that the dharmakaya is a primordial buddhasubstance into which buddhas dissolve and from which buddhas arise, becoming embodied as the nirmanakaya (what you would see if you ran into Prince Siddhartha in northern India about 2500 years ago) and also simultaneously

as the sambhogakaya, where the special attributes are visible, but only to other buddhas and boddhisattvas. Each buddha, upon attaining enlightenment, attains the dharmakaya, re-appearing in the nirmanakaya and sambhogakaya. And so it goes, simultaneously, in all times, all places, all universes/worlds/realms.

III. Bodhisattvas

If there are many, many buddhas, there are an unbelievable number of bodhisattvas. In one paragraph on the third page of Cleary’s translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra there is a list of 20: “These and others were the leaders — there were as many as there are atoms in ten buddha-worlds.” Also as numerous

as atoms in one buddha-world are the multiple-body spirits, the footstepfollowing spirits, the sancturary spirits, the city spirits, the earth spirits, the mountain spirits, the forest spirits, the herb spirits, the crop spirits, the river spirits, the ocean spirits, the fire spirits, the direction spirits, the night spirits… The Mahayana pantheon is a very crowded pantheon indeed.

Here we will limit ourselves to the four great bodhisattvas, the ones who flank Shakyamuni Buddha in altar paintings, the ones mentioned, in this order, in the 6th stanza of the Homage to the Three Jewels: Manjusri, Samanthabadhra, Avalokitesvara, and Ksitigarbha. Additionally, Avalokitesvara is the main

personage in the Heart Sutra, both the 1,000 Eyes and Hands Sutra and the Great Dharani essentially invoke him, and of course he (or maybe she) is invoked in the Kwan Se Um Bosal chant.

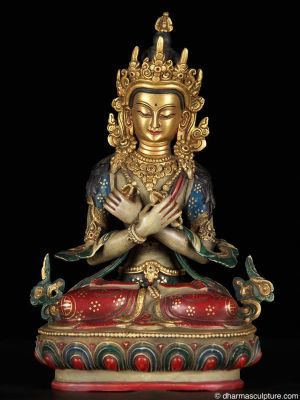

Boddhisattvas are always physically depicted as gender ambiguous (although they are in some sense necessarily male — in conventional, traditional Buddhism, women cannot attain enlightenment), without muscle tone, and in long, ornate, flowing robes. Each bodhisattva has identifying iconography.

III.1. Manjusri

Manjusri is the bodhisattva of wisdom: Mun Su Sari is his name in Sino-Korean, and he is introduced with the epithet Dae Ji (great wisdom); his name in Sanskrit translates as Gentle Radiance. He appears in the Prajnaparamita Sutras (but not in the condensed version we know of as the Heart Sutra), the Lotus

Sutra11 (where he leads the eight year old daughter of the Naga King to enlightenment — first she has to briefly transform into a man), the Avatamsaka Sutra (where, in the final chapter, he sends Sudhana on his journey and receives him back at the end) and is a major character in the Vimalakirti Sutra,

where he loses a debate with the layman Vimalakirti over the meaning of non-duality: Manjusri explains at length that saying nothing is the best way to explain non-duality, but when Vimalakirti is asked to explain non-duality, he simply remains silent.

Manjusri is always male. He was born from a lotus that sprang from a tree that was pierced by a ray from Buddha’s forehead — no parents, not exactly a human being, a sort of instant Bodhisattva. His iconography includes a flaming sword in his right hand, and a copy of the Prajnaparamitra Sutra cradled on a lotus flower in his left. In some depictions he is riding a lion.

His pure land is to the east. When he eventually becomes a buddha he will be known as the Buddha of Universal Sight. Even though he is a bodhisattva and not a buddha, it is difficult to tell the difference. Descriptions of bodhisattvas are as florid as those of buddhas; their powers are almost indistinguishable from those of buddhas, since they too are able to enlighten sentient beings (which is why Cleary calls them “enlightening beings” instead of enlightened ones).

For example, here is how Shariputra praises Manjusri in the final chapter of the Avatamsaka Sutra:

“See the inconceivable purity of form of Manjushri, along with the celestial and earthly beings, his variety of marks and embellishments, the purity of his sphere of radiance, his web of light beams developing countless beings, extinguishing all miseries, his wealth of followers, embraced by past virtues, arraying the path, which is eight steps wide.12 See the magnificent arrays of the procession on the path facing the realms in all directions as they go,

with overflowing great treasures… all the world chiefs are showering clouds of offerings in respect; from the curl of hair between the eyebrows of all

11 The Lotus Sutra is especially important in Tiantai (in Japanese, Tendai) Buddhism, and, in particular, in Nichiren Buddhism (a major modern offshoot is Soka Gakkai) whose major practice is chanting (in Sino-Japanese) “homage to the Lotus Sutra” — namu myoho renge kyo; Dogen was originally a Tendai monk,

hence Soto Zen is strongly influenced by the Lotus Sutra. 12 Clearly a reference to the eightfold path: correct view, correct resolve, correct speech, correct action, correct livelihood, correct effort, correct mindfulness, correct meditation.

buddhas from the ten directions, spheres of networks of light beams emanate; uttering all teachings of buddhas, and enter Majushri’s head.”

III.2. Samantabhadra

Samantabhadra is the bodhisattva of action: his name in Sino-Korean is Bo Hyon, and his epithet is Dae Haeng (great action); his name in Sanskrit means Universal Virtue. He is one of the fifty or so beings who Suddhana encounters in the Avatamsaka Sutra; also in the Avatamsaka Sutra is a list of the

special ten vows he made on his path to buddhahood. In altar paintings he stands at the Buddha’s right. He is often depicted riding a six-tusked white elephant, sometimes also carrying a parasol — this elephant is often associated with the elephant whose tusks pierced the side of Queen Maya in a dream

which heralded Shakyamuni Buddha’s birth. In some depictions he appears feminine, similar to Kwan Yin. Another iconic aspect of Samantabhadra is the small Vairocana buddha appearing in his headdress. The vows which appear towards the end of the Thousand Eyes and Hands Sutra (the lines beginning “won a yong ni sam ak to…” — “won” means “vow”) are Samantabhadra’s vows.13

Samantabadhra is a major character in the Avatamsaka Sutra. Throughout the sutra he is the personification of the bodhisattva type, as Vairocana is the personification of the buddha type. The third chapter is devoted to Samantabadhra’s meditation practice. Many boddhisattvas speak in the Avatamsaka Sutra,

but Samantabadhra is given three monologues: in the fourth chapter, he explains the origins of the world in the powers, vows, resolve and actions of buddhas, boddhisattvas, and sentient beings, as well as natural law; he then goes on to describe the universe in its multitude of worlds. In the fifth

chapter he describes the Flower Bank World, and in the sixth he gives the various origins and incarnations of the central buddha of this sutra, Vairocana. The tenth chapter is devoted to his vows.

The epilogue to the Lotus Sutra is devoted to him. All we know of his origins is that he was born in the east, in, as Gene Reeves translates it, the Land of Pure Wonder. He is presented as the bodhisattva through whom people can approach Shakyamuni Buddha. Here is a taste of how he is presented (Reeves’ translation):

“The body of Universal Sage Bodhisattva is unlimited, the range of his voice is unlimited, and the forms of his image are unlimited. When he wants to come to this world he uses his own divine powers to shrink his body to a smaller size. Because of the three hindrances of the people in Jampudvipa are heavy, through the power of his wisdom he transforms himself and rides a white elephant.14

13 The four vows that appear before those lines (beginning “won a jong hye sog won myong”) are more general vows to practice, act correctly — including attaining “victorious fortunes” — and eventually attain Buddahood. 14 Jampudvipa is the corner of the universe where human beings live.

“The elephant has six tusks and is supported by seven legs. Under its seven legs are seven live lotus flowers. The elephant is as white as snow, the most brilliant of whites. Even crystal or the Himalayas cannot be compared with it. The body of the elephant is four hundred and fifty leagues long and four hundred leagues tall.

“At the tips of its six tusks are six bathing pools, and in each bathing pool grow fourteen lotus flowers… [and, many paragraphs later, when practitioners are directed to ask to see Samantabadhra’s physical body, recite sutras, and make offerings we are told] All people should be regarded as though they were the Buddha, and all living beings as though they were one’s father and mother.

“While a follower is reflecting in this way, Universal Sage Bodhisattva will immediately send forth a ray of light from the tuft of white hair between his eyebrows…”

And so on. Notice the ray of light from a tuft of hair between the eyebrows, which is also associated with buddhas. In Mahayana cosmology, buddhas and bodhisattvas tend to blend into each other.

III.3. Avalokitesvara

Avalokitesvara, a.k.a. Kwan Se Um Bosal,15 a.k.a. Kwan Yin, a.k.a. Kannon, a.k.a. Kanzeon, is the bodhisattva of compassion. His/her epithet is Dae Bi (great compassion). In all of these languages his/her name means “perceive world sound” — if you truly perceive the sound of the universe, you perceive the

suffering of its inhabitants, and your compassion awakens. An alternative translation from the Sanskrit, which seems to have gained popularity several centuries later, translates as “Lord who looks down [on the world”], and it is in this form that he appears in the Sino-Korean Heart Sutra as Kwan Ja Je.

Avalokitesvara is the most gender-flexible of the four main bodhisattvas. The male figure of Avalokitesvara was born from a beam of light emanating from Amitabha’s eyes (which is why Kwan Yin/Avalokitesvara is always depicted with a figure of Amitabha in her/his headdress). The female figure of Kwan Yin was

a princess who, much like Amitabha, vowed to save all beings from suffering and, after many kalpas of sincere practice, was reborn a bodhisattva — this short version leaves out the many melodramatic complications, which involve, depending on the source, unwilling marriage, execution, giving up her eyes and arms as medicine to save her father’s life, and so on.

15 And no, I have no explanation for why Koreans always add “Bosal”, i.e., “Bodhisattva” to her name.

Most of the iconography involves the female figure of Kwan Yin, and it is quite varied. There is the representation with 1,000 hands and 1,000 eyes (the eyes appear in the palms of the hands) — that is the iconography behind the title of the 1,000 Eyes and Hands Sutra which we chant at the beginning of

special chanting. There is the famous water-moon pose: sitting on a rock with the left foot dangling (presumably in a pond or lake or river), the right foot bent at the knee, one arm resting on it — the beautiful Kwan Yin statues in the Nelson Art Gallery in Kansas City, and in the Honolulu Art Museum,

have this pose. In many depictions she wears white (for purity) and holds a flask of pure water. In many depictions she stands on a cloud and pours water from the flask on a baby, generally considered in Asia to be an aborted fetus (she is often turned to by women who have unwillingly had abortions). She is

the bodhisattva you turn to when you or someone you know has some kind of difficulty — that is the Kwan Se Um Bosal chant, as well as the 1,000 Eyes and Hands Sutra. She has a bewildering number of names, each expressing an incarnation with a special attribute (some of these are listed in the 1,000 Eyes and

Hands Sutra, and translated in the notes at the back of our chanting book). The Great Dharani is a long mantra16 which, while untranslatable, as almost all mantras are, is clearly dedicated to and focused on Kwan Yin. She is arguably the most popular bodhisattva in all of Buddhism.

Avalokitesvara is a major character in a number of sutras, the two most important being the Lotus Sutra and the Heart Sutra. Chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra is devoted to Avalokitesvara. In this chapter Avalokitesvara is presented as a bodhisattva who is always on duty, ready to spring into action when called

upon. We can call on Avalokitesvara to save us from danger from others, to save us from our own lusts and desires, to grant us well-being. But, most important, if we call on Avalokitesvara to preach the dharma, he will appear in whatever form is needed: any kind of being, of any rank and any gender. The

chapter ends with a poem that sums up the blessings of Avalokitesvara, much of which has been incorporated into a chant in the Japanese tradition. Here is a sample of two of many stanzas of the chant (this is Roshi Sunyana Graef’s translation, used at the Vermont Zen Center):

“If someone comes to hurt you And pushes you into a great fire pit If you think on the power of Kanzeon The fire pit will change into a pond…

“If you’re cast adrift upon the great ocean And meet danger from dragons, fish and demons, If you think on the power of Kanzeon The waves will not drown you…”

16 A dharani is exactly a long mantra; the Great Dharani, originally transliterated from the Sanskrit, is known by a number of names in different liturgies and is chanted widely, with variations according to the language of transliteration, in various Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions.

And so on. A small piece of this chapter is also found in the Thousand Eyes and Hands Sutra, in the stanza beginning “a yak hyang do san…”.

In discussing Avalokitesvara’s appearance in the Lotus Sutra I was using the male pronoun, because that is how s/he is presented in the sutra. In the Kanzeon chant, it is the female aspect to which one chants. In the Thousand Eyes and Hands Sutra we have both.

The Avalokitesvara we meet in the Heart Sutra is not the lavishly described compassionate savior of the Lotus Sutra. Instead of springing into action, Avalokitesvara dwells far apart from every inverted view in Nirvana.17 As we all know from chanting it at nearly every practice period, the Heart Sutra —

more precisely the Heart of Great Wisdom Practice Sutra — is austere: no imagery, no lavish descriptions, no elaborately staged interactions among various beings as in other sutras. Instead, Avalokitesvara, speaking to Shariputra, clearly and simply lays out the Mahayana response to the early abhidharma

(Buddhist psychology, epistemology and ontology), focusing on emptiness and on negation of the abhidharma’s categories. We learn that it is the practice of great wisdom that saves us from all suffering and distress, and the sutra ends with the sort of self-referential praise that marks many Buddhist sutras. The sutra tacitly identifies compassion and wisdom — the personification of compassion in some sense (pacé Manjusri) personifying both.

Finally, there is the wonderful Kanzeon Sutra in Ten Lines which comes from China and is chanted vigorously in Japanese schools (translation is by Zen Master Hae Kwang): Kanzeon! Namu butsu yo (Kanzeon, at one with Buddha) Butsu u in yo, butsu u en (Caused by Buddha, close to Buddha) Buppo so en jo

raku ga jo (and to Buddha, dharma, sangha.) Cho nen Kanzeon! Bo nen Kanzeon! (Morning thoughts are Kanzen; evening thoughts are Kanzeon) Nen nen ju shin ki, nen nen fu ri shin. (Thoughts thoughts arise in mind; all these thoughts are just this mind.)

III.4 Ksitigharba

17 In our chant, we say “perverted” view; others use “deluded.” The Chinese word literally means “upside-down,” so “inverted” or “confused” are better translations.

The name Ksitigharba means earth-womb, (sometimes translated as earth-treasury or earth-store) but despite that name he is invariably depicted as male, usually as a monk with either a shaved head or green hair and a tall staff bearing six rings at the top (supposedly to scare away tigers) and holding a

wish-fulfilling jewel. The things that look like fuzzy slippers in some depictions are the lotus flowers he stands on. Sometimes he is depicted with small children clinging to his robe. Sometimes he is himself depicted as a child-monk.

He appears in our chanting in the Homage to the Three Jewels as Ji Jang Bosal; his epithet is Dae Won Bon Jon (Great Vow Original Face). Traditionally, the Ji Jang Bosal chant is chanted for 49 days after someone dies; it is incorporated into the memorial ceremony.

Ksitigharba has two origin stories. In one, he is a young girl frantic with fear that her recently dead mother is in hell. Moved by her dedication, Buddha shows her a vision of hell and that her mother had already been reborn in heaven. Moved by the suffering she saw in hell, the girl vows that she will save

all beings from it. In the second origin story, he is a Korean prince who becomes a monk in China, performs miracles, and whose body does not decay after death; in fact, it can be seen today, dehydrated, on Mount Jinhua in China. The Korean prince may or may not be an incarnation of the young girl.

Ksitigarbha does not appear in any of the major sutras, but has his own sutra, the Sutra of Ksitigarbha, a complete English translation of which, by Upasaka Tsao-tsi Shih, can be found online.

In this sutra, Buddha is preaching to his mother Queen Maya in the Tushita Heaven when “all the separate transformational Ksitigarbha Bodhisattvas came from all the hells in hundreds, thousands, myriads and millions of unthinkable, indescribable, immeasurable, inexpressible, countless numbers of worlds to

assemble… At that time, all the separate transformational Ksitigarbha Bodhisattvas from all the different worlds reassembled into one entity” who pledges to deliver beings from the hell realms. Most of the sutra is spent detailing various kinds of karmic retribution or reward, practices such as recitation of the Buddha’s name, and so on, as well as giving the first origin story of Ksitigarbha. The vision of Ksitigarbha is of a being who willingly faces inconceivable horror and can redeem beings who seem irretrievably lost.

Despite Ksitigarbha’s lack of centrality in Buddhist scripture, he is one of the most beloved bodhisattvas in Buddhism — in Japan, where he is known as Jizo, he is as or perhaps even more popular than Avalokitesvara (although, as in our practice, it is Avalokitsvara who is the dominant figure in the liturgy). Ksitigarbha is the guardian of children, of pregnant women, of travellers, of firefighters, and of the dead. Like Avalokitesvara, he is

especially associated with aborted or miscarried fetuses, or stillborn babies (all known as “water babies”). In Japan there are special shrines devoted to the ritual of commemorating water babies by dressing Jizo statues with red caps and red clothing. In this country, Great Vow Zen Monastery in Oregon has extended this tradition

by holding several ceremonies each year to memorialize children who have died, and also general memorial ceremonies focusing on Jizo.

IV. Buddha’s companions/disciples

The three companions of Shakyamuni Buddha we are most familiar with are Mahakasyapa, Ananda, and Shariputra — there were, of course, many more, male and female, rich and poor — one, Vimalakirti, even has a sutra named after him. Mostly they show up in kong-ans and sutras. Since we are concentrating on chants here, we will only discuss Shariputra, to whom Avalokitesvara speaks in the Heart Sutra.

IV.1. [[Shariputra

Shariputra means “son of Shari” and, indeed, Shari was his mother’s name. He was one of the Buddha’s closest companions, and is considered one of the founders of the abidharma. He was close companions with another of the Buddha’s disciples, Mahamaudgalyayana, who had supernatural powers, and was

considered, along with the Buddha, one of Ananda’s major teachers. Shariputra, as founder of the abhidharma, is a commanding figure in Theravada Buddhism. The Mahayana sutras in which he appears include the Lotus Sutra and the Avatamsaka Sutra: in the former, his future buddhahood is predicted; in the latter, he introduces and praises Manjusri in the final chapter. So far everything is standard. But this changes in the Heart Sutra and the Vimalakirti Sutra.

The Heart Sutra is, essentially, Avalokitesvara’s teaching to Shariputra. And what it teaches is, in large part, the anti-abidharma. The extensive list of categories that are negated in the Heart Sutra, ranging from abstractions such as form and feeling to concrete objects such as eyes and ears and going on

to basic Buddhist categories such as suffering and origination of suffering are all categories extensively discussed in the abhidharma. The narrative essence of the Heart Sutra is Avalokitesvara telling Shariputra that Shariputra’s greatest achievement is completely mistaken.

Shariputra fares even worse in the Vimalakirti Sutra, where he is essentially a comic foil throughout. He is fretful, worried, needs reassurance. Vimalakirti’s room is too small for everyone to fit! The chairs are too high to sit in! The flowers raining down make a mess! The goddess producing them doesn’t understand the dharma!18 What are all these beings going to eat? What is the explanation for all the miraculous events? Why does everyone have such

a strong sweet smell?19 And when he gives the standard formulation of how reciting even four lines of this sutra will result in complete unexcelled enlightenment, he does it by querulously asking the Buddha if this will really happen. He

18 Actually, she does, a lot better than Shariputra, and when he tells her prissily that females cannot attain enlightenment she even turns him into a woman, briefly, which really freaks him out. 19 Because they ate fragrant rice, he is told.

is completely clueless. Among the grand Mahayana pantheon of near-perfect beings, he is recognizably human.

V. Reading list?

As the memorial ceremony says, “we have recited from a number of sutras…” The question is: which ones are important to read?

First, a caveat: for a lot of people a lot of the time, reading sutras is a distraction from practice. I was certainly that way for the first ten years or so of my practice. It took a lot of bowing, chanting, and sitting before I could see where the words were pointing. Until then, sutras only confused me. If

you try to read a sutra and find it only confuses you, do yourself a favor and put it down. That said, you may be a person for whom reading sutras encourages your practice. In which case, you should read at least some. Buddhism is replete with sutras, most of them either minor or specialized. There is no need to try to read all of them. In fact you can’t — traditionally there are 84,000; I don’t know if anyone’s actually tried to list all of them.

The major sutras we’ve mentioned are the Avatamsaka Sutra, the Lotus Sutra, and the Vimalakirti Sutra. The Vimalakirti Sutra is in many ways the most accessible — it has a plot, a touch of humor, and its teaching point is clear. I recommend Burton Watson’s version. The Lotus Sutra has wonderful stories

and images in it (the father rescuing his children from the burning house; the dharma rain which rains down equally on all plants…) and exists in two good translations, Burton Watson’s and Gene Reeves’ (Reeves includes the epilogue on Samantabhadra; Watson doesn’t). The Avatamsaka Sutra is incredibly long —

about 1200 pages of large pages and small type — and ornate. If you are interested, look at the Thomas Clearly translation. We barely mentioned it, but the Diamond Sutra is perhaps the most essential sutra to read in Zen other than the Heart Sutra. Red Pine’s translation and commentary is recommended.

Interlinear translations by Zen Master Hae Kwang of some of our chants are available on the Kansas Zen Center website, on the Resources page.

And, for general reference, an extensive bibliography can be found on the website of Prof. Jimmy Gu, a dharma heir of the great Chan master Shen Yen: http://myweb.fsu.edu/jyu2/links.htm.

Judy Roitman (Zen Master Bon Hae)

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Stan Lombardo (Zen Master Hae Kwang), Zen Master Dae Kwang, and Maria Chan for their invaluable help and suggestions