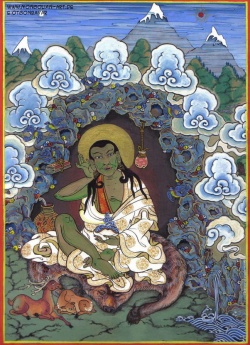

Who Was Guṇaprabha?

by Paul K. Nietupski, John Carroll University

Guṇaprabha, like many Indian Buddhist authors, is a mysterious figure. It is difficult to assess what of Guṇaprabha’s biographical data is factual and what is embellishment invented to endow him with a high level Buddhist pedigree. The inherited tradition describes him as an erudite monk and later an abbot from a brahmin family, who lived and worked in Mathurā.2 He is called a student of [page 3] fourth-century Vasubandhu, mentor to seventh-century King Harṣa, and a contemporary of one Ratnasiṃha (ca. 649).3 His sectarian affiliations are likewise expansive, as he writes of Vinaya, is associated with Vaibhāṣikas, is called a bodhisattva,4 is credited with authorship of commentaries on two Mahāyāna sūtras,5 his monastic texts and commentaries include language suggestive of Mahāyāna concerns,6 and he is said to have had audiences with the Buddha Maitreya in the course of his many sojourns to Tuṣita, Maitreya’s heaven.

The biographical details are uncertain, and beyond the suggestions in his writings it may well be that the authorities sought to authenticate Guṇaprabha by associating him with pre-eminent Buddhist figures and circumstances. The Tibetans heard these messages and revered Guṇaprabha in the list of the famous masters of Indian Buddhism, the “Six Ornaments and Two Superiors.”7 If Guṇaprabha’s pedigree is a matter of embellishment for religious ends, one might well also ask if, instead of his reputation, were the Indian Guṇaprabha’s compositions and the Tibetans’ adoption of the Vinayasūtra corpus expressive of a modified, reduced size of [page 4] medieval Indian Buddhist monasticism, perhaps the unappealing and cumbersome detail of the older and larger Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya, and even a reduced concern with classical Vinaya and monastic concerns?8 If this was the case in India, were the Tibetan motives for adopting the corpus as Davidson suggests, namely that monastic concerns were less of a priority in Tibet? The study of Guṇaprabha and his texts along with the recent studies on early Tibetan Buddhism can shed some light on the nature of Indian and Tibetan religions and institutional development.

[2] See L. Chimpa and A. Chattopadhyaya, trans., Taranatha’s History of Buddhism in India (Simla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study, 1970), 176; S. A. Banerji, Traces of Buddhism in South India: 700-1600 A. D. (Calcutta: Scientific Book Agency, 1970), 95; D. K. Barua, Vihāras in Ancient India: A Survey of Buddhist Monasteries (Calcutta: Indian Publications, 1969), 89.

[3] Guṇaprabha, Vinayasūtra and Autocommentary on the Same by Guṇaprabha, ed. P. V. Bapat and V. V. Gokhale (Patna: K.P. Jayaswal Research Institute, 1982), xxii states that this mention of Ratnasiṃha “…may be a marginal remark of some later reader of the text.” The Vinayasūtra and Autocommentary, xxii, quotes J. Takakusu, A Record of Buddhist Religion as Practised in India and the Malay Archipelago, AD 671-695. 2nd Edition (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1982), LVIII, 184: “I-tsing mentions one Ratnasiṃha as living then at Nālandā at about 649 A.D.”

[4] In the opening of the Vinayasūtra Autocommentary.

[5] Guṇaprabha, Byang chub sems pa’i sa’i ’grel pa [*Bodhisattvabhūmivṛtti] and Byang chub sems pa’i tshul khrims kyi leu’i bshad pa [*Bodhisattvaśīlaparivartabhāṣya], in The Tibetan Tripiṭaka: Peking Edition, Vol. 112, ed. D. T. Suzuki (Tokyo: Tibetan Tripitaka Research Institute, 1955).

[6] Guṇaprabha, Vinayasūtra, xliv remarks: “There is a reference to vajropamāsamāpatti (sūtra 1) before attaining sopadhiśeṣanirvāṇa. This may well indicate the author’s Mahāyānism.” See the passage “…even those endowed with compassion amongst those in this world with human bodies in fortunate circumstances have many numbers of impurities, obstacles, and ugliness”: anukampakaiḥ dṛṣṭi [T. kṣāṇa] saṃpanne ca manuṣyatve bahavo ’tra, Guṇaprabha, *Vinayasūtravṛttyabhidhānasvavyākhyānam (Guṇaprabha, Vinayasūtra and Autocommentary, 13.3); thugs brtse ba dang ldan pa rnams kyis dal ’byor phun sum tshogs pa’i mi’i lus nyid ’di la/, Guṇaprabha, ’Dul ba’i mdo’i ’grel pa mngon par brjod pa rang gi rnam par bshad pa, in the Degé Tengyur Series, vol. 161, no. 12, zhu (New Delhi: Delhi Karmapae Chodhey, 1986), 12b.6. See references to various types of bodhi in the closing pages of the *Vinayasūtravṛtti attributed to Guṇaprabha.

See Guṇaprabha, ’Dul ba’i mdo’i ’grel pa, in the Degé Tengyur Series, volume 165, no. 16, lu (New Delhi: Delhi Karmapae Chodhey, 1986), 343a.3 ff: “sangs rgyas kyi sku/”; see the discussions of śīla and samādhi (Guṇaprabha, ’Dul ba’i mdo’i ’grel pa, 21); see Guṇaprabha, ’Dul ba’i mdo’i ’grel pa, 16b.5: dgra bcom pa dang rang sangs rgyas la mi byao bla la med pa’i sangs rgyas pas na yang dag rab mkhyen [ce]s so/; see The First Dalai Lama, Dge ’dun grub pa, Legs par gsungs pa’i dam pa’i chos ’dul ba mtha’ dag gi snying po’i don legs par bshad pa rin po che ’phreng ba, in The Collected Works of the First Dalai Lama dge ’dun grub pa, vol. 1 (Gangtok: Dodrup Lama Sangye, Deorali Chorten, 1981), 55b.6: brtul zhugs can gyis bla ma bas/; see Shes rab bzang po, Kun mkhyen mtsho sna ba, ’Dul ba mdo rtsa’i rnam bshad nyi ma’i ’od zer legs bshad lung gi rgya mtsho (Karnataka: Drepung Losel Ling, n.d.), 62a.3: brtul gshug can/. See Shes rab bzang po, ’Dul ba mdo rtsa’i rnam bshad for extensive comments on Mahāyāna themes, for example pakpé tsültrim (Shes rab bzang po, ’Dul ba mdo rtsa’i rnam bshad nyi ma’i ’od zer legs bshad lung gi rgya mtsho, 73b.1 ff). See Guṇaprabha, ’Dul ba’i mdo’i ’grel pa, 9a.4: snying rje che ba/.

[7] Nāgārjuna, Āryadeva, Asaṅga, Vasubandhu, Dignāga, and Dharmakīrti (fl. ca. seventh century) are the Six Ornaments. Śākyaprabha and Guṇaprabha are the Two Superiors.

[8] See Georges Dreyfus, The Sound of Two Hands Clapping: The Education of a Tibetan Buddhist Monk (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), where the author describes the relative marginalization of the Vinaya documents in modern Tibetan Buddhism; Vinaya texts do not represent modern Tibetan monastic practice. Davidson makes a similar assessment of Tibetan priorities and behavior in the ninth century and later, suggesting at times rather little concern for strict monastic discipline (Ronald M. Davidson, Tibetan Renaissance: Tantric Buddhism in the Rebirth of Tibetan Culture [[[Wikipedia:New York|New York]]: Columbia University Press, 2004], 120-122). Perhaps a similar scenario served as a motive for Guṇaprabha’s abbreviated composition, and for its adoption by the Tibetans.