Conflict Resolution and Peaceful Society: A Buddhist View

Conflict Resolution and Peaceful Society: A Buddhist View

Dr. Arvind Kumar Singh

Assistant Professor, School of Buddhist Studies & Civilization

Gautam Buddha University, Greater Noida,

Gautam Budh Nagar,

Uttar Pradesh-201308 INDIA

Email: arvindbantu@yahoo.co.in, arvinds@gbu.ac.in

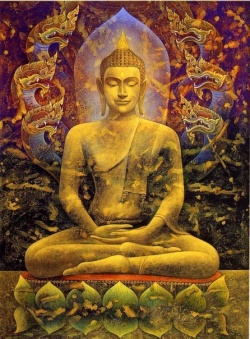

Abstract: The era after Second World War was started a new type of conflict based on economic, hegemony, under development, etc. In some areas of the world due to the cold war people suffered economically, socially and politically. After establishing the WTO regime a new phase of globalization came into force. The major idea behind it was consumerism and the market economy which ultimately led to socio-economic crisis in the world and the idea of sustainability of world has become endangered. In the contemporary world, violence manifests in many ways, such as quarrels, armed conflicts, military occupations, economic exploitations, and prejudices based on language, race, caste, religion, gender or sexual orientation. Buddhism has long been celebrated as a religion of peace and non-violence. With its increasing vitality in regions around the world, many people today turn to Buddhism for relief and guidance at the time when peace seems to be a deferred dream more than ever. This proposed paper tends to deal with the Buddhist vision of conflict resolution and peaceful society and also addresses the Buddhist perspective on the causes of violence and ways to prevent conflict and to realize peaceful society to maintain the equilibrium in the world order.

The Buddha appeared at a time that is widely recognized as a period of political, social and spiritual unrest in India. The canonical texts of Theravada Buddhism are testimony to the prevalence at this time of wars between kings and kings, and between kings and the republican states. The texts also reflect social conflicts arising from crime and poverty, and interminable disputes and confrontations among the many competing religious and philosophical schools of the time. The Buddha had occasion to comment on all these conflicts. It is high time to talk about the world peace. The world has long been in need of peace. The changing scenario of the globe has pushed it to the brink of war and catastrophe. There are weapons of mass destructions in the form of chemical, biological, nuclear war-heads and so on. The peace will not be established until the self consciousness would reveal in the human beings. In this nuclear age, the establishment of a lasting peace on the earth represents the primary condition for the preservation of human civilization and survival of human beings. Nothing perhaps is so important and indispensable as the achievement and maintenance of peace in the modern world today. Peace refers to love, kindness, well being, equity, human dignity and socio-economic justice. Thus, peace in today’s world implies much more than mere absence of war and violence.

Conflict as depicted in Buddha’s Teachings

Quite verily Buddhism has generally been viewed as associated with non-violence and peace. These virtues have been strongly represented in its value system. This does not mean, though, that Buddhists have always been peaceful; Buddhist countries have had their fair share of war and conflict for most of the reasons that wars have occurred elsewhere. Yet, it is difficult to find any plausible ‘Buddhist’ rationales for violence. Buddhism has some particularly rich resources for deployment in dissolving conflict. It is generally observed that Buddhism has had a general humanizing effect throughout much of Asia. It has tempered the excesses of rulers and martial people, helped large empires (for example, China) to exist without much internal conflict, and rarely, if at all, incited wars against non-Buddhists. Moreover, in the midst of wars, Buddhist monasteries have often been heavens of peace. For Buddhism, the roots of all unwholesome actions - greed, hatred and delusion - are viewed at the root of human conflicts. When gripped by any of them, a person may think ‘I have power and I want power’, so as to persecute others. Tīṇ’ imāni kho bhikkhave akusalamūlāni. Katamāni tīṇi? lobho akusalamūlaṃ, doso akusalamūlaṃ, moho akusalamūlaṃ…contd.[1]

Conflict often emanates from attachment to material things: pleasures, property, territory, wealth, economic dominance or political superiority. Furthermore, the Buddha says that sense-pleasures lead on to desire for greater sense-pleasures which leads on to conflict between all kinds of people, including rulers, and thus quarrelling and war.[2] The Mahāyāna poet Sāntideva pointed it in his ‹iksā-samuccaya, citing the Anantamukha - nirhāradhāranī, “Wherever conflict arises among living creatures, the sense of possession is the cause”.[3] Apart from actual greed, material deprivation is seen as a key source of conflict.

The Buddha is once said to have prevented a war between the Sākiyas and the Koliyas.[4] Both used the waters of a dammed river that ran between their territories and when the water - level fell, the labourers of both peoples wanted the water for their own crops. They, thus, fell to quarrelling and insulting each other and when those in power heard of these insults, they prepared for war. By his meditative powers, the Buddha is said to have perceived this, then flown to the area to hover above the river. Seeing him, his kinsmen threw down their arms and bowed to him, but when people were asked what the conflict was about; at first no-one knew, until at last the labourers said that it was over water. The Buddha then got the warrior-nobles to see that they were about to sacrifice something of great value - the lives of warrior - nobles -- for something of very little value - water. They, therefore, desisted. In this way, over the centuries, Buddhist monks have often been harnessed by kings to help negotiate an end to a war. Mahāyāna texts explicitly suggest that Buddhists should also try to see that warring parties are more ready to settle their differences.

In one of the Jātaka story,[5] the Bodhisattva is said to have been a king and was told of the approach of an invading army. In response, he says ‘I want no kingdom that must be kept by doing harm’, that is, by having soldiers defend his kingdom. His wishes are followed and when the capital is surrounded by the invaders, he orders the city’s gates to be opened. The invaders enter and the king is deposed and imprisoned. In his cell, he develops great compassion for the invading king (who will karmically suffer for his unjust action), which leads to this king experiencing a burning sensation in his body. This, then, prompts him to realise that he had done wrong by imprisoning a virtuous king. Consequently, he releases him and leaves the kingdom in peace. Here, the implied message is that the king’s non-violent stance managed to save the lives of many people on both sides. In line with this approach, are such verses as: Conquer anger by love, conquer evil by good, conquer the stingy by giving, conquer the liar by truth.[6]

Though he should conquer a thousand men in the battlefield; yet he, indeed, is the nobler victor who should conquer himself.[7]

Akkodhena jine kodhaṁ, asādhuṁ sādhunā jine, jine kadariyaṁ dānena saccena alikavādinaṁ. Etādiso ayaṁ rājā, maggā uyyāhi sārathiti.[8]

Furthermore, in Jātaka tales, the content of the first of these is said to have been the policy of the Buddha in a previous life as a King Brahmadatta of Banaras, in contrast to a king who only repaid good with good and evil with evil.

Of course, such an approach does not always save lives and indeed it is said that the Sākiya people came to be annihilated when they did not defend themselves against aggressors. Again, in the eleventh century, when invading Muslim Turks smashed Buddhist monasteries and universities, it appears that the monks offered no resistance.

At one place, it is said that — “the fearless monk Puṇṇa who told the Buddha that he was going to live and teach among the people of Sunāparānta, who were said to be very fierce people.”[9] And, he went there and went on to gain many disciples among the people of Sunāparanta. In Indian history, while Buddhists were sometimes persecuted by Hindu kings, there is no record of persecution of others by Buddhists.

Among the central values of Buddhism are those known as the ‘divine abiding’ (Brahmavihāras): loving kindness, compassion, empathetic joy and equanimity. Allied to these is the virtue of patience or forbearance (Pali khanti, Skt Koeānti) as exemplified in the Khantivādi-Jātaka. All such values are directly relevant in defusing conflicts, the practice of which will make these less likely to occur in the first place.

In addition to it, Buddhaghosa gives various reflections, in his Visudhimagga, for undermining hatred or anger.[10] These can be seen as valuable in many contexts as methods of removing the plower of these destructive emotions and thus undermining the psychological roots of conflict.

It is imperative to not that, within the Buddhist monastic community, harmony is much valued and systems were developed to deal with differences within it, such as disputes over matters of monastic discipline. Furthermore, the Buddha explains that there are seven ways[11] to settle a dispute: reaching a consensus by drawing out the implications of agreed principles; majority voting if this fails; overlooking monastic offences which the guilty part cannot remember committing; overlooking apparent offences committed when a person was out of his mind; setting aside an offence which has been acknowledged with the promise not to repeat it; censure of a monk who only acknowledges a serious offence under cross-questioning after having denied it; and lastly ‘covering over with grass’. This final method is to be used if the two parties have taken to open quarrelling.

Amongst, the legion of Buddhist teachings and principles, ethics relevant to the shunning use of violence are the following:

1. The first precept, i.e. the commitment to avoid intentional harm or killing of any sentient being, whether directly or by the agency of another person. 2. The emphasis on loving kindness and compassion. 3. The ideal of ‘right livelihood’, a factor of the Eight fold Path to Nirvāna, which precludes making a living in a way that causes suffering to others. Among the specifically listed forms of ‘wrong livelihood’ is living by ‘trade in arms’.[12]

Given these emphases, can war and similar forms of violence ever be justified? The Buddhist path aims at a state of complete non-violence based on insight and inner strength rooted in a calm mind. Yet, those who are not yet perfect, living in a world in which others may seek to gain their way by violence, still have to face the dilemma of whether to respond with defensive violence. Pacifism may be the ideal but in practice Buddhists have often used violence in selfdefence or defence of their country, not to speak of sometimes going in for aggressive violence like any other group of people. Ordinary Buddhists may feel that they are not yet capable of the totally non-violent response, particularly as they are still attached to various things which they feel may sometimes need violence to defend. Of course, they could give these up by becoming monks or nuns, but they may not feel ready for this level of commitment.

The Indian emperor, Aśoka (268 - 239 BCE) is widely revered by Buddhists as a great exemplar of Buddhist ethics, partly because of his emphasis on non-violence. While encouraging his people in this and other Buddhist moral norms, he himself abandoned his forebears’ custom of violent expansion of the realm.

This kaleidoscopic survey of Buddhism, thus, exhibits that the tradition has strong resources to draw on for conflict resolution, but that these resources and related ideals must sometimes become better known and applied more fully. Buddhists did little to stem the war, though they are now active in promoting peace. The post-colonial period has left a legacy of instability and social readjustment in several Buddhists lands, and it is clear that, in certain quarters, there has been a danger of religious revival degenerating into hatred and anti-colonial nationalism degenerating into xenophobia. Ironically, this is a good illustration of the Buddhist teaching that ignorance and dogmatism are at the root of much human suffering.

As the peoples and nations of the world prepare to enter the twenty-first century during a time of dramatic social change and increasing global interdependence, considerable attention is being given to the task of developing a new global ethics. Moreover, in the wake of tumultuous times the world is undergoing at present- such as sport in terrorism, rising fundamentalism, ethnic conflicts and political aggression; Buddhist heritage eternally stands as a harbinger of peace and harmony.

A particularly striking example of the Buddha’s comments on conflicts is found in the Sakkapañha Sutta of the Dīgha Nikāya. Here Sakka tells the Buddha that all peoples “wish to live without hate, harming, hostility or malignity, and in peace.” In spite of this, they actually live in “hate, harming one another, hostile and malign”[13]. Sakka asks why this is so. This launches a discourse in which the Buddha traces the cause of conflict and hostility to bonds of jealousy and avarice, thence to likes and dislikes desire and finally to what is called papañca[14], which among other things means the “expansion” or distortion of perception. In another discourse, we find the Buddha engaged by an unnamed questioner in a dialogue on “quarrels and disputes”[15]. Again he traces the origin of disputes to sense perception and to its distortion or the condition of papañca..

In one of his discourses i.e. the Madhupindika Sutta,[16] the Buddha teaches how to handle perceptions such that they do not lead to latent tendencies[17]; and this is the art of living without conflicts. When this is referred to the Elder Mahākaccāna for a fuller explanation, he gives an analysis of the various stages of sense-perception as they occur in any ordinary person. He points out that “thinking” (vitakka) follows perception and it is this that leads to distorted perception (papañca) and thence to violence and conflict.

The Vāseṭṭha Sutta[18] gives another explanation of the origin of conflict where it is mentioned that his is flawed perception, which really amounts to ignorance or delusion. On this ground we can say that the Buddha sees ignorance or flawed perception as the factor that is responsible for all conflicts. Theravada canonical texts often trace the origin of conflicts to opinions, beliefs and ideologies. The Discourse to Vāseṭṭha [19] deserves more close attention and in this epic exposition of the Buddha’s teaching of the biological indivisibility of humankind analyses methodically how the notion of “difference-by-birth” has come to occupy such an important place in our consciousness. In four words - dīgharattaṃ anusayitaṃ diṭṭhi-gatam ajānataṃ - verse 649 of the discourse brilliantly sums up the unconscious evocative power of the idea of “difference-bybirth”. Here “view” (diṭṭhi), “ignorant persons” (ajānataṃ) and “latent tendency” (anusaya) are interlinked. A mistaken view has remained in memory for a long time and has become a mental habit. An example of this is the notion of nāma-gotta or name-and-clan, i.e., the common assumption “I am of such-and-such lineage” - same as differentiation-by-birth. The last word, a negative form from the root ¤ā- (to know) indicates how, unconsciously or without knowledge[20], the notion of differentiation by birth has taken root in the mind. Racial consciousness is unexceptionably an expression of this differentiation-by-birth, which the Vāseṭṭha Sutta determinedly exposes as a misconception, a designation formulated from place to place[21].

In diṭṭhi we see the flawed cognitive aspect of human consciousness. The cognitive, however, is not its only aspect. Counted among mental tendencies are also craving, pride and arrogance, illwill and aggression[22]. These are among the more complex affective characteristics of the flawed consciousness mentioned in the canonical texts of Theravada as common causes of conflict and violence in society. For example, the Anguttara Nikāya[23] gives greed, hate and ignorance as those wherewith one creates misery for others, overcome by the hunger for power. What propels belligerent conduct is the thought, “I have power, I want power” ( balava’mhi, balattho iti). M I.86 f. says that it is due to lusts (kāma) that kings, brahmins, householders, parents, children, brothers, sisters, and friends and colleagues get into disputes and conflicts (kalaha/viggaha/vivāda) and end up fighting with weapons of destruction.

On the basis of above discussion, one can clearly says that the conflict originates from the same roots as suffering. For that very reason, the way to the resolution of conflicts cannot be different from the Noble Eightfold Path which the Buddha recommended for the “pacification” of suffering. It seems to me that the above would be an approximation to a valid Buddhist approach to the causation of conflicts.

However, Buddhism does not adopt the skeptical and pessimistic view that we are destined to remain in this state. The Buddha explained that change is a very difficult process but not an impossible one. In fact the whole of Buddhism is an enterprise “to transform man from what he is to what he ought to be”[24], or rather to what he has the potential to be. Angulimāla, the serial killer is an example of one who underwent a sudden change of heart. Usually however, there are no such short cuts, only a systematic, long-term programme of moral education. It is for such change in society that the Buddha gave his discourses and founded the Sangha.

The stress on a gradual process of change and training, beginning with moral habits, stretches like a thread across the Buddhist texts. There is a firm belief that discipline, education and the taking of one step at a time can lead people from a state of relative ignorance to greater wisdom. The possibility of gradual change must be admitted alongside the sudden change of Angulimala.[25]

Buddhism and Peaceful Society

How to establish peaceful society is the most burning issue in the present world scenario. In this dispensation, Buddhism can play a decisive role for providing sustaining and preserving the world peace. The foundation of peace and security can strengthened within the framework of Buddhism, which is quintessentially tolerant, cosmopolitan and portable. The duty of religion is to guide humanity to uphold certain noble principles in order to lead a peaceful life and to maintain human dignity. The Buddha introduced a righteous way of life for human beings to follow after having himself experienced the weakness and strength of human mentality. Buddhism is essentially a practical doctrine, dedicated primarily to the negation of suffering and only secondarily to the elucidation of philosophical issues. But of course, the two realms — the practical and the philosophical are not connected. The thought (Pariyatti) and the practice (Paṭipatti) are to move together side by side, just like the two wheels of chariot for righteous and smooth way-faring for human life. It is the system of only one problem and one solution with a path existing between the two. The only problem is the suffering of human beings (Dukkha) and the solution is the attainment of eternal peace (Nibbāna) and the path to attain this is Eight Fold Path (Aṭṭhāngika Magga), which is a dynamic principle gradually leading towards amelioration and complete harmony in the universal social order, non-violent in character and saturated with peace and tranquility.

The fundamental goal of Buddhism is peace, not only peace for human beings but peace for all living beings. The Buddha taught that the first step on the path to peace in understanding the causality of peace. The Buddha was of the view that peaceful minds lead to peaceful speech and peaceful actions. Of all the teachings of the Buddha, one can say that Bodhicitta is the forerunner of peace. The Buddha exhorts:

- "Cetanā ahaṃ bhikkhave, kammaṃ vadāmi

(O monks, volition is the action.)

The Buddha further states in the Dhammapada as under[26]:

- Sabba Pāpassa akaranāni,

- Kuśalassa upasampadā

- Sacitta pariyodapānaṃ,

- Etam Buddhana Sāsanam.

which means 'abstaining from all sorts of sin, doing good to all living beings and making one's mind pure is the Buddhadhamma. So when Bodhicitta is attained, peace is established and violence and hatred are annihilated. In this regard, the Kaliṇga war of King Aśoka may be cited. According to the 13th Rock Edict[27], King Aśoka adopted, "Dhammaghosh" i.e. the sound of Righteousness instead of "Bherighosa" i.e. the word of trumpet after having seen the mass instruction of life and materials during the war.

To inculcate the sense of maintaining peace, tranquility and serenity in the world, one must follow the middle path, which has eight gradual steps (Ayameva āriyo atthangiko maggo). As a whole, the Eight Fold Path has three steps, namely, Sila (Comprising Right Speech or Samma-vāca, Right Action or Samma-kammānto and Right Livelihood or Samma-ājivo), Samādhi (comprising Right Effort or Samma-vayāmo, Right Mindfulness or Samma-sati and Right Concentration or Samma-samādhi) and Paññā (comprising Right View or Samma-ditthi and Right Resolve or Samma-samkappo).

Śila is the first step which curtails the physical and vocal misdeeds, Samādhi curtails the mental misdeeds and Paññā makes the dawn of Right Understanding under the light of which the nature of reality is visualized. Śila i.e. attainment of supreme wisdom are the three basic principles of Buddhism to be disentangled from entanglement. When this principle is duly followed, four defiling factors (âsava), five hindrances (Nivāraṇa) and ten fetters (Samyojana) will automatically came to their end and there must be appearance of four sublime ways of living (Brahmavihāra), five perfection (Pāramitā) to cease the mental disorder. This is why the middle path is considered as the most suitable therapy for treatment of common neurosis of human beings which ultimately will be an answer to resolve conflict.

Enmity is the biggest hurdle for achieving peace in the world. It is universal truth that enmity begets enmity. The Buddha exhorts in the Dhammapada[28] that by enmity none conquers, by non-enmity enmity will be conquered. It is universal truth ‘(Na hi verena verani sammantidha ‘Kudacanam, Averena ca Sammanti esa dhammo sanantano)’. It is again Bodhicitta which overthrows enmity and thus paves the way for peace and harmony in the world over. Peace, according to early Buddhist tradition, is a psychic phenomenon. What we call peace is a nearer expression of "Santa Citta". This can be attained by a layman through following the Brahmaviāāra teachings of the Buddha, which is construed as the sublime ideas. Brahmavihāra consists of four sublime virtues namely - friendliness (mettā), comparison (karuṇā), joy (muditā) and equanimity (upekkhā). These four sublime virtues can create a congenial atmosphere amongst the persons and nations of the world.

Mettā destroys ill - will and ego and helps in achieving love and peace for the human beings, which is eloquently mentioned in the Mettā Sutta of the Sutta Nipāta by the following Gāthā[29] “Mātā, yathā niyaṃ puttaṃ, āyusa ekaputtamanurakkhe, Evaṃ pi sabbabhutesu maṃsaṃ bhavaye aparimanaṃ”. Compassion (Karuṇā) means eradication of sufferings of other - 'Karunati dayā, anuddayā, hadayanampanaṃ va.' It is not a simply expression towards being in suffering but a positive attitude to be one with the suffering of others and making right efforts for its gradual minimization - paradukkhe sati hadayakampanaṃ, kinati va paradukkhaṃ, hiṃsati vinaseti ti attho.[30] Karuṇā has the characteristics of evolving the mode of removing pain, suffering, and manifestations of kindness. Compassion is the virtue which uproots the wish to harm others. It makes people so sensitive to the sufferings of others and causes them to make these sufferings so much their own that they do not wish to further increase them. Mettā, Karuṇā, Muditā and uppekkhā are in the same way helpful in getting peace and tranquility all around. The Buddha told the human beings to adopt the principle of Brahmavihāra[31]:

- Titthaṃ caraṃ nisinno va.

- Sayano va yavatassa vigata middho,

- Etam satim adhittheyya,

- Brahmametam vihāram idhamahu.

Buddhist individual and social doctrine of loving kindness (Mettā) has been associated with non-harming (Ahiṃsā) and is the ethical wellspring for the Buddha's view of domestic polity as well as problems of war and peace. Buddhism is a gentle religion where equality, justice and peace reign supreme. Buddhist theory enjoins the kind to conquer only by righteousness with resort to force and violence. The Buddha’s main concern is to teach the five moral precepts of Buddhism to the laymen. And this was the prelude to the establishment of peace in the world. The Buddha preached non-violence and peace as universal message. He did not approve of violence or the destruction of life and declared that there is no such thing as a just war. He taught that the victor breeds hatred, the defeated lives in misery. He who renounces both victory and defeat is happy and peaceful. Not only did the Buddha teach non-violence and peace, he was the first and only religious teacher who went to the battlefield personally to prevent the outbreak of war. He diffused tension between the Śākyas and the Koliyas who were about to wage war over the waters of river Rohini. He also dissuaded King Ajātśatru of Magadha from attaching the kingdom of Vajjis. And then the Buddha formulated the seven fold policy of state in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta of the Dīgha Nikāya.

The Buddha did not propagate any gospel and dogma. The entire corpus of sermons and teachings is based on pragmatic realism and rational thinking. The Buddha exhorted - "Atta dipo Viharatha" (be light unto yourself). He further states in the Aṭṭhavagga of the Dhammapada[32]. "Atta hi attano natho ko hi natho parasidya" (A man is his lord himself, not come one else)

The point is when rational thinking prevails, peace comes automatically. This is applicable to the world peace also. The Buddha gave his followers a full fledged freedom to think, decide and act. He did not thrust any ideas upon them. Thus, the nationalistic thought based on individualistic freedom paves the way for world peace.

It is well known that there are instances in the Theravada Canon where the question of social conflict on a mass scale has been addressed. In these, we see that the roots of conflict lie not only in individual consciousnesses, but also that the very structure of society encourages those roots to grow. Two of the best examples of this are the discourses named Cakkavatti-sīhanāda and Kūṭadanta, both of the Dīgha Nikāya[33]. The Cakkavatti-sīhanāda shows how successive “universal monarchs” kept social problems at bay by following the sage dictum “whosoever in your kingdom is poor, to him let wealth be given”.[34] Peter Harvey sums up that “if a ruler allows poverty to develop, this will lead to social strife, so that it is his responsibility to avoid this by looking after the poor and even investing in various sectors of the economy”. Where this is not done, the result will be crime and lawlessness, as is shown in the Cakkavatti-sīhanāda Sutta.

The Cakkavatti-sīhanāda Sutta presents a disturbing picture of how a society can fall into utter confusion because of a lack of economic justice. The extremes reached are far greater than anything envisaged in the Kūṭadanta Sutta and they stem from the state’s blindness to the realities of poverty[35]. Harris goes on to show how according to the Sutta, criminality in society spirals to the point when people behave as if they see one another as wild beasts: it is as if an evolutionary drift towards extreme violence has taken place. It is significant that the sutta does not concentrate on the psychological state of the people. The obsessive cravings, which overtake them, are traced back to the failure of the state rather than to failings in their own adjustments to reality. The root is the defilement in the state — the rāga, dosa and moha in the king which afflict his perception of his duty. I believe that Harris would not preclude the fact that the psychological state of the people had indeed deteriorated, but that in this instance the Sutta emphasizes the responsibilities of the state; I believe she would agree that the Sutta does not suggest that the deteriorated psychological condition of the people can be restored and radically improved merely by the state adopting the correct social and economic policies. Such a (Marxian) conclusion would run counter to the Buddhist teaching that that there can be no external source of liberation.

The Buddha’s comments on hearing of the wars between Ajātasatthu and Pasenadi Kosala do not appear to be an endorsement of war; rather they portray his considered opinion that war only leads to misery and degradation: “Victory breeds hatred, the defeated live in pain. Happily the peaceful live, giving up victory and defeat”[36]. “The slayer gets a slayer (in his turn), the conqueror gets a conqueror… . Thus by evolution of kamma, he who plunders is plundered”[37].

At Sutta Nikaya[38], we get a picture of Sakka who defeats his adversary Vepacitti in battle, but does not even retaliate verbally when Vepacitti insults him in the presence of his subordinates. This is not because he is afraid or weak, but because, being a wise person, he knows that one who does not react in hate towards a hater wins a victory hard to win, which serves the true interests of both contestants.

The question of war cannot be discussed without considering the social significance of the ethical precepts, because war of necessity involves the violation of the first precept. It would be a mistake to assume that the importance given to the observance of the precepts is solely because it is a means of personal moral improvement. We should not fail to note that two things are said about the precepts: (1) one should observe them (samādāna) and (2) one should also advocate and applaud their observance by others (samādapana and samanu¤¤a)[39]. Because of the long held prejudice that Buddhism is predominantly concerned with individual “salvation”, the social significance of such Buddhist views tends to be ignored. The so-called “military option” becomes even more incompatible with Buddhism when we realize that the precepts are invested with this wider significance.

That it is possible for individuals to achieve, and abide in, peace and sanity is of course the message of Buddhism[40]. On the other hand, the Buddha did not even pursue the “noble doubt” that arose in him once, as to whether it would be possible to run a state righteously, without killing, conquering, or creating grief to self and others[41]. It is true that the cakkavatti king is portrayed as going about with the “fourfold army”, bringing “rival” rulers under his nominal suzerainty[42], but he achieves this without firing a single arrow and he does not do so for power or glory but for the promoting of ethical values. Yet it is not unreasonable to infer from this passage that Buddhism found it impossible, even under the best of circumstances, to visualize a state that functions without the backing of an army. It is only a commentary on the human condition, not an endorsement of war.

Buddhist Solution to Conflict Resolution

No one needs to be reminded that every day people find themselves in conflict, ranging from minor discomfort to serious confrontations. When people cannot tolerate moral, religious or political differences, conflict is inevitable, and often costly. Thich Nhat Hanh says, "To prevent war or conflict, to prevent the next crisis, we must start to have a dialogue for peace right now. When a war or conflict has begun, it is already too late. If we and our children practice ahimsa in our daily lives, if we learn to plant seeds of peace and reconciliation in our hearts and minds, we will begin to establish real peace and, in that way, we may be able to prevent the next war or conflict." Conflict can open avenues of change and provide challenges. Conflict-resolution skills do not guarantee a solution every time, but they can turn conflict into an open opportunity for learning more about oneself and others. Conflict can be both positive and negative, constructive and destructive, depending on what we make of it. Surely it is rarely static-it can change any time. The Buddhists would call this aniccā. Nothing is permanent. Everything is changing. Yet in many conflicts people are so attached to their views, and tend to blame the other side without examining their own position critically. In this case there cannot be any dialogue for peace and reconciliation. However, we can sometimes alter the course of a conflict simply by viewing it differently. We can even turn our flight into fun. Transforming conflict into reconciliation and dialogue for peace is an art, requiring special skills. Indeed, in resolving a conflict skilful means (upāya kosala) is a keyword in Mahayana Buddhist terminology.

A resolution of conflicts will be possible if we are able to realise the necessity to learn how to loosen the grip exerted by the unwholesome “roots” on our collective character at least to some extent. Sooner or later, humanity will have to make a valiant struggle towards this end, if it is to escape from the spiral of hate and criminality in which it is now engulfed. The three major inputs discussed above are derived from the Buddhist conception of attachment (lobha), aggression (dosa) and delusion (moha) as the three roots of unwholesome action and the opposites of these, namely freedom from attachment, aggression and delusion (alobha/ adosa/ amoha) as being the roots of wholesome action. The next two are from the principles of right speech, and mutuality of benefit; the last is a practical example derivable from the administration of the Buddhist community committed to liberation.

John A McConnell has recently written an excellent manual, Mindful Mediation: A Handbook for Buddhist Peace Makers where he applies the Buddhist Four Noble Truths to conflict very clearly, by explaining (1) the truth of suffering or conflict as part of the human condition; (2) the truth of the rise of suffering as the root of conflict, i.e. greed, hate and delusion. The challenge of the Second Noble Truth is to be aware of these psychological roots of conflict. This is more difficult than it might seem, because we do not normally experience delusion, greed and hate merely as mental phenomena, but as emotions already bound up with objects - often other people. In everyday, unmindful, existence we experience a particular object as desirable, beautiful, repulsive, etc. We do not discriminate between the object, the feeling, the desire, and the process by which the desire has been cultivated, for example, through advertising and fantasy. Similarly, if we are involved in conflict, we perceive the hated person as selfish and contemptible. Once we understand the Second Truth, we can then embark on the third truth of cessation that peace can emerge from conflict. It is essential to see conflict, with all its messiness and pain, as an opportunity for peace-making. It challenges us to develop a peace process that engages with the roots of conflict. Then we can proceed to the fourth truth of the cessation of suffering i.e. peace is the way of life.

Meditation can be an excellent tool for this, for understanding ourselves and developing compassion for and understanding of those with whom we are in conflict. For example, we can begin our contemplation with the person we hate or despise the most. We contemplate the image of the person who has caused us the most suffering. Contemplate the bodily form, feelings, perceptions, mind and consciousness of this person. With a deeper understanding of our fellow human beings, especially those in very different situations from ourselves and who we may be in conflict with, we cannot help but see the similarities and connections between us, which in turn can serve as an invaluable tool in conflict prevention and resolution. Thus we can cultivate seeds of peace. We can apply this technique not only at personal levels, but also to society and nation states, to structural violence. The Dalai Lama is an example of a person who has inspired many of us to love our enemy by cultivating seeds of peace. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi does the same in Burma, as does the Venerable Maha Gosananda in Cambodia.

On the basis of above discussion we can say that the prevalent conflict in the society (world) can be resolved through Buddhist teachings for personal regeneration are also eminently applicable on the path to social regeneration. Here I would like to outline briefly some of the inputs that have been derived from Buddhist teachings and the overall Buddhist outlook on life as discussed above from the Buddhist scriptures, which could be of help in the quest for establishing peaceful society then (Buddha’s Period) and now (Present World). I would like to conclude with Thich Nhat Hanh's saying on peace which is very relevant in present world scenario: There is no enlightenment outside of daily life. Living in this marvelous reality ~ living in peace, is something we all want. But I would like to ask: Do we have the capacity of enjoying peace? If peace is there, will we be able to enjoy it, or will we find it boring? To me, peace and happiness and joy and life go together, and we can experience the peace of the divine reality right in the present moment. It is available, inside us and around us. If we are not able to enjoy that peace, how can we make peace grow?

Works Cited

- Harris, Elizabeth J. 1994. Violence and Disruption in Society. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society (Wheel Publication . No. 392/393 )

- Harvey, Peter. An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 2000.

- Jayatilleke, K.N. Undated. Dhamma, Man, and Law. Singapore : The Buddhist Research Society, Loy, David R, “How to Reform a Serial Killer: The Buddhist Approach to Restorative Justice.” In Online Journal of Buddhist Ethics , Vol. 7 (2000)

- Nanamoli, Bhikkhu and Bodhi, Bhikkhu, 1995. The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society (M)

- Norman, K.R., 1984. The Group of Discourses (Sutta Nipata), Volume I. London: Pali Text Society. (Sn)

- Premasiri, P.D. 1972. The Philosophy of the Atthakavagga, Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society (Wheel Publication No. 162)

- Tilakaratne, A. 1993. Nirvana and Ineffability. Kelaniya: Kelaniya University

- Walshe, Maurice, The Long Discourses of the Buddha. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1996.

Footnotes

- ↑ A. I. 201-202.

- ↑ MLS. I. 86-87.

- ↑ Ss. 20.

- ↑ Dhp. Verse No. 197-199. 173-174.

- ↑ J. II. 400-403. Idaṁ vatvā mahārājā kaṁso Bārāṇasiggaho dhanuṁ tūṇiñ ca nikkhippa saññamam ajjhupāgamīti.

- ↑ Dhp. Verse No. 223. 190.

- ↑ Ibid. Verse No. 103. 97. Yo shassaṁ sahassena, saṅgame mānuse jien. Ekañ ca jeyya m’attānaṁ, sa ve saṅgāmajuttamo.

- ↑ J. II. 3-4.

- ↑ M. III. 268-269.

- ↑ PP. 324-331.

- ↑ M. II. 247-250.

- ↑ A. V. 177-178.

- ↑ Walshe, Maurice, The Long Discourses of the Buddha. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1996: 328

- ↑ We can broadly accept Nanananda’s explanation of papa¤ca as conceptual proliferation, i.e., it refers to all that we “think” about a person or an object perceived, all that we associate with that object/person (e.g., regarding him/her as a representative of a particular class, caste, race, colour, ideology etc., which may arouse deep-seated prejudices and emotions). Such “proliferation” amounts to misperception or distorted perception. On the other hand authentic perception is what the Buddha describes thus: “In the seen there will be just the seen” (Ud 8): it is not coloured by “expansion” or “proliferation”.

- ↑ Sn 862 – 874: Norman, K.R., The Group of Discourses (Sutta Nipata), Volume I. London: Pali Text Society, 1984: 144 f.

- ↑ M. I.108 ff.

- ↑ Nanamoli:201 translation; “perceptions no more underlie that Brahmin” i.e., “underlie” the perceiver, is not quite clear. Nanamoli, Note 227 has “perceptions no longer awaken the dormant underlying tendencies to defilements”. I take sannà na anusenti as “perceptions do not leave a residue” or do not produce a residual tendency. This applies to the awakened person who is free from papa¤ca. We should expect sa¤¤à anusenti : “perceptions leave a residue”, as mark of the ordinary person.

- ↑ Sn: 115 ff.

- ↑ Sn 594-656

- ↑ It is not that one is ignorant for other reasons and then comes to hold this mistaken view; rather, the ignorance and the view are mutually causative.

- ↑ Sn 648 . sama¤¤à h’esa lokasmiü nàmagottaü pakappitaü/ sammuccà samudàgataü tattha tattha pakappitaü : “ For what has been disgnated name and clan in the world is indeed a mere name . What has been designated here and there has arisen by common assent” – Norman: 107

- ↑ S.III. 254 names 7 forms of anusaya: kàmaràga, pañigha, diññhi, vicikicchà, màna, bhavaràga, and avijjà.

- ↑ A. I. 201.

- ↑ Jayatilleke, K.N. Undated. Dhamma, Man, and Law. Singapore :The Buddhist Research Society, Loy, David R, “How to Reform a Serial Killer: The Buddhist Approach to Restorative Justice.” In Online Journal of Buddhist Ethics , Vol. 7, 2000: 52.

- ↑ Harris, Elizabeth J. 1994. Violence and Disruption in Society. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society (Wheel Publication . No. 392/393 ) :38.

- ↑ Sanghasen Singh (Tr.) Dhammapada(1977) , p. 32

- ↑ P.V Bapat (Ed.), 2500 Years of Buddhism (1966), p. 56

- ↑ Sanghasen Singh (Tr.), op. cit. p. 15

- ↑ Bhikkhu Dhammarakshit (Ed. & Tr.) Sutta Nipāta 1995, p. 36

- ↑ A»»hasālini (ed.) Tripathy R.C. 1989, p. 340.

- ↑ Dharamrakshit Bhikkhu, op.cit., p. 36

- ↑ Sanghasen Singh (Tr.) op. cit., p. 30

- ↑ D.III.58-79 and D.I.127-149 ; Walshe, Maurice, The Long Discourses of the Buddha. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1996: 395 ff. and 133 ff.

- ↑ D.III.70 f.

- ↑ Harris, Elizabeth J., Violence and Disruption in Society. Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society (Wheel Publication No. 392/393), 1994: 23.

- ↑ S.I.83.

- ↑ S.I.85.

- ↑ S. I. 221.

- ↑ See A.I. 194-196 and ii.191 f.: the aluddha/aduññha/amāëha observes the precepts and advocates their observance by others ( param pi tathattàya samàdapeti ) whereas the luddha/duññha/māëha violates them and advocates their violation by others, 1.297-299: killing, getting others to kill and applauding others when they kill lead to hell ; abstaining from killing, getting others to abstain and applauding others when they abstain lead to heaven. So for all the “ways of action” kammapatha. (The words samàdapana and samanu¤¤a occur here). Dhammika Sutta of Sn shows that there is a three-fold meaning in the first precept : (1) pàõaü na hane, (2) na ca ghàtayeyya, (3) na cànuja¤¤à hanataü paresaü (Sn 394).

- ↑ Dhp 197 depicts persons of insight as living in harmony and happiness, even though society is full of haters: susukhaü vata jãvàma/ verinesu averino. Dhp 103/104 say that no divine force can overturn the victory of the person who conquers self, not others.

- ↑ S. I. 116 : sakkà nu kho rajaü kàretuü ahanaü, aghàtayaü, ajinaü, ajàpayaü, asocaü asocàpayaü dhammena?

- ↑ D.III.62.

Source

Submitted by: Dr. Arvind Kumar Singh