Difference between revisions of "BUDDHIST CHINA AND SOUTH INDIA"

(Created page with "thumb|250px| By DR. I.K. SARMA Nin hao, Indu = Hello! Welcome, Hindu; hen hao = excellent! that is haw an Indian is warmly greeted in China. You are! T...") |

m (1 revision: Robo text replace 30 sept) |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

| − | Nin hao, Indu = Hello! Welcome, Hindu; hen hao = excellent! that is haw an Indian is warmly greeted in China. You are! The snow skinned chubby faces and black-haired, fish-eyed youth of China are lovely to look at but all in uniforms – girls in white pants and short shirts and men in Mao’s coat, all blues with the red strip collars, monotonous in apparel and appearance. But there underlies a sincere love and affection to | + | Nin hao, Indu = Hello! Welcome, [[Hindu]]; hen hao = {{Wiki|excellent}}! that is haw an [[Indian]] is warmly greeted in [[China]]. You are! The snow skinned chubby faces and black-haired, fish-eyed youth of [[China]] are lovely to look at but all in uniforms – girls in white pants and short shirts and men in Mao’s coat, all blues with the red strip collars, monotonous in apparel and appearance. But there underlies a sincere [[love]] and {{Wiki|affection}} to “{{Wiki|Indus}}” in {{Wiki|general}} a term that is [[sweet]] to utter and cherished by the Chinese–who instantly go deep in their [[thoughts]] on {{Wiki|ancient Indian}} and {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|cultural}} bonds. Yet {{Wiki|Indians}} are rarely seen in [[China]] and the reverse is also true. Why these most {{Wiki|ancient}} civilized Asians moulded in great eastern [[traditions]] and common {{Wiki|cultural}} links remain somewhat isolated with each other? |

| − | I had the fortune of seeing this great country in October 1983 under an Indo-China Cultural Exchange Programme. My visit was mainly academic and to get a personal glimpse of the Chinese architectural and artistic wealth, mainly Buddhist affiliation. The historical and archaeological sites and Museums in and around Beijing, Gansu, Shanxi, Henan and Canton provinces of China were visited by me in a whirlwind tour, very ably arranged by the Central Cultural Relics Bureau, People’s Republic of China, Beijing. | + | I had the [[fortune]] of [[seeing]] this great country in October 1983 under an Indo-China {{Wiki|Cultural}} Exchange Programme. My visit was mainly {{Wiki|academic}} and to get a personal glimpse of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} architectural and artistic [[wealth]], mainly [[Buddhist]] affiliation. The historical and {{Wiki|archaeological}} sites and Museums in and around {{Wiki|Beijing}}, Gansu, Shanxi, Henan and Canton provinces of [[China]] were visited by me in a whirlwind tour, very ably arranged by the {{Wiki|Central}} {{Wiki|Cultural}} [[Relics]] Bureau, People’s {{Wiki|Republic}} of [[China]], {{Wiki|Beijing}}. |

| − | Chinese chronicles mention about a gold statue of Buddha being brought to China in 122 B.C. (Western Han period). But it is fairly certain that China received Buddhism from India by the beginning of the Christian era (Eastern Han (25-200 A.D.) through the South-East Indian coast and Ceylon. | + | {{Wiki|Chinese}} chronicles mention about a {{Wiki|gold}} statue of [[Buddha]] {{Wiki|being}} brought to [[China]] in 122 B.C. (Western Han period). But it is fairly certain that [[China]] received [[Buddhism]] from [[India]] by the beginning of the {{Wiki|Christian}} {{Wiki|era}} (Eastern Han (25-200 A.D.) through the South-East [[Indian]] coast and [[Ceylon]]. |

[[File:Bo1 1280.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bo1 1280.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The three famous Chinese Travellers, Fa-hien (40-411), Yuan-Chwang (629-646), and It-Sing (671-695) have made enormous contribution to be the development of Buddhism in China and their numerous translation works on the Buddhist Sutras, Vinaya and Abhidharma, made China a reservoir of these treasures of Buddhist art, thought and literature. The foundations for such a prolific scholarly impetus must have been laid by a few centuries earlier to this trio. A Brahmi inscription dated to mid-third century A.D. from the ancient city of Sriparvata Vijayapuri in the Nagarjunakonda valley (Dt. Guntur, Andhra Pradesh), refers to the pilgrimage of some acharyas (scholars) to China and other countries for proselytizing the Buddhist order. These monks, together with other acharyas hailing from Kashmira, Gandhara and Ceylon, besides other places in India, worshipped the Bodhi Vriksha Prasada (Bodhi tree pavilion), extant on the Chula Dharmagiri Vihara monastrey at Nagarjunakonda. Nagarjunakonda’s Sriparvata is hallowed as the seat of Acharya Nagarjuna (2nd century A.D.), the founder of Madhyamika school of Mahayana Buddhism which spread all over China. At this place the Mahasamghika sects made headway and its principal schools like Chaityaka and Sailas propagated on meritorious acts such as the creation, decoration and worship of chaityas and eventually deified the Buddha and Bodhisattvas Mahayana Buddhism thus gained a high degree of popularity among the masses and crossed the Indian frontiers very swiftly. It is not one-sided. Chinese emperors greatly respected Indian Buddhist teachers and monks. There was a meaningful cultural exchange. Kanchipuram finds mention in a Chinese text dated to first century A.D. and called huang chao. It is said that Chinese emperors sent presents to the King of Fuang Cha in A.D. 1-6. Although initially Buddhism was humbled by the native Confucianism and was regarded as “Barbarian | + | The three famous {{Wiki|Chinese}} Travellers, [[Fa-hien]] (40-411), Yuan-Chwang (629-646), and It-Sing (671-695) have made enormous contribution to be the development of [[Buddhism in China]] and their numerous translation works on the [[Buddhist Sutras]], [[Vinaya]] and [[Abhidharma]], made [[China]] a reservoir of these [[treasures]] of [[Buddhist art]], [[thought]] and {{Wiki|literature}}. The foundations for such a prolific [[scholarly]] impetus must have been laid by a few centuries earlier to this [[trio]]. A Brahmi inscription dated to mid-third century A.D. from the {{Wiki|ancient}} city of Sriparvata Vijayapuri in the Nagarjunakonda valley (Dt. Guntur, Andhra Pradesh), refers to the pilgrimage of some acharyas ([[scholars]]) to [[China]] and other countries for proselytizing the [[Buddhist]] [[order]]. These [[monks]], together with other acharyas hailing from [[Kashmira]], [[Gandhara]] and [[Ceylon]], besides other places in [[India]], worshipped the [[Bodhi]] Vriksha [[Prasada]] ([[Bodhi tree]] pavilion), extant on the Chula Dharmagiri [[Vihara]] monastrey at Nagarjunakonda. Nagarjunakonda’s Sriparvata is [[hallowed]] as the seat of [[Acharya]] [[Nagarjuna]] (2nd century A.D.), the founder of [[Madhyamika]] school of [[Mahayana Buddhism]] which spread all over [[China]]. At this place the [[Mahasamghika]] sects made headway and its principal schools like Chaityaka and Sailas propagated on [[meritorious]] acts such as the creation, decoration and {{Wiki|worship}} of [[chaityas]] and eventually deified the [[Buddha]] and [[Bodhisattvas]] [[Mahayana Buddhism]] thus gained a high degree of popularity among the masses and crossed the [[Indian]] frontiers very swiftly. It is not one-sided. {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|emperors}} greatly respected [[Indian]] [[Buddhist]] [[teachers]] and [[monks]]. There was a meaningful {{Wiki|cultural}} exchange. Kanchipuram finds mention in a {{Wiki|Chinese}} text dated to first century A.D. and called huang chao. It is said that {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|emperors}} sent presents to the [[King]] of Fuang Cha in A.D. 1-6. Although initially [[Buddhism]] was humbled by the native {{Wiki|Confucianism}} and was regarded as “Barbarian [[religion]]”, by the [[time]] of the Eastern Ts’ in (or Jin 317-420) and the Wei (386-551) dynasties’ firm foundations were laid for works of [[Buddhist art]] and [[Buddhism]] gained the {{Wiki|status}} of a state [[religion]] by about 500 A.D. The translations undertaken by the {{Wiki|Chinese}} traveller-trio were mostly based on the [[Madhyamika]] works expounded by [[Acharya]] [[Nagarjuna]] and elaborated later on by such great luminaries as [[Bhavaviveka]] and [[Kumarajiva]] (344-413). In particular, Huen {{Wiki|Tsang}} studied the treaties of Abhidiharma with the [[monks]] at Dhanyakataka, the present Amaravati-Dharanikota in Dt. Guntur not far from {{Wiki|Sri}} [[parvata]] Vijayapuri of Nagarjunakonda. Among the 657-Sanscrit works [[caused]] by him from [[India]] for {{Wiki|translations}}, 15 were Mahasamghika works. In particular, this famous {{Wiki|Chinese}} traveller makes mention of a [[Stupa]], hundred feet high, built by {{Wiki|Mauryan}} [[emperor]] at Kanchi and [[tradition]] assigns another [[Dharma]] [[soka]] Maharajavihara at Kaverippumpattinam (Dt. Thanjavur). A [[Buddhist temple]] specially meant for visiting {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[monks]] existed during the [[time]] of Pallava [[King]] Narasimhavarman - II (695 - 722) at Nagapatinam. These were {{Wiki|witness}} of a seaborne {{Wiki|cultural}} exchange between [[Buddhist]] China-India and [[Ceylon]]. It might be noted that [[Bodhidharma]], the well-known founder of [[Chan]] sect who lived at the ‘Sheaolin [[temple]] (Mount - Songshan, Province Henan) hailed from this part of [[India]]. So also, Dinnaga (5th century), the founder of {{Wiki|medieval}} [[Nyaya school]], hailed from Kanchi, a centre for Pali-Buddhism. It appears then that {{Wiki|South}} {{Wiki|East}} [[India]] with its long coastal line and convenient anchorages has been in [[contact]] with [[China]] and {{Wiki|South}} {{Wiki|East Asian}} centres during the early centuries of the {{Wiki|Christian}} {{Wiki|era}}. |

[[File:Buddhist-monk500.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Buddhist-monk500.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The consolidation of Buddhism led to the practice of making cliff grottoes and decorating them with wall paintings of Buddhist deities and legends. The most famous among these exist in North and West China. They are Kizil grottoes in Xin Jiang, the Mogo grottoes at Dunhuang (Gansu), Yuankang grottoes at Datong (Shanxi), Longmen caves at Louyang (Henan). In all these, as in Ajanta - Aurangabad, not only carved out figures, but sculptures in relief, extensively painted murals on the walls characterise the Indian impact and influences of Buddhist art. A variety of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas reflect great physical charm with all the Mahapurusha Lakshanas in a truly Indian style. The ten-thousand Buddha cave at Long man (pl- II), is worthy of note. The seated Vairochana Buddha, 17.14 metres high, (pl- I), among other massive sculptures is a superb example of Chinese carving dated to the beginning of 7th century A.D. Besides the rock cut caves, the fossilized sand caves of Thousand Buddhas, Dunhuang (Gansu) contain unimaginably big straw built day sculptures installed in their shrines in there. The over-size image of seated Buddha in wood in the main cave (No. 096) measures 33 metres high and is within a seven storeyed pavilion with pent roofs, marking each storey and dated to 9th century AD. The wooden images are so well finished and painted in pleasing colours. The fine toranga arches with fiying apsaras and Gandharvas carrying garlands the maidens with floating garments around fully – blossomed lotus ceilings datable to early 5th-6th century AD., are some of the very attractive Indian style carvings at Longmen caves as well as painted ceilings of Dunhuang. | + | The consolidation of [[Buddhism]] led to the practice of making cliff [[grottoes]] and decorating them with wall paintings of [[Buddhist]] [[deities]] and legends. The most famous among these [[exist]] in {{Wiki|North}} and {{Wiki|West}} [[China]]. They are Kizil [[grottoes]] in [[Xin]] Jiang, the Mogo [[grottoes]] at {{Wiki|Dunhuang}} (Gansu), Yuankang [[grottoes]] at Datong (Shanxi), Longmen [[caves]] at Louyang (Henan). In all these, as in [[Ajanta]] - [[Aurangabad]], not only carved out figures, but sculptures in relief, extensively painted murals on the walls characterise the [[Indian]] impact and [[influences]] of [[Buddhist art]]. A variety of [[Buddhas]] and [[Bodhisattvas]] reflect great [[physical]] charm with all the Mahapurusha Lakshanas in a truly [[Indian]] style. The ten-thousand [[Buddha]] {{Wiki|cave}} at Long man (pl- II), is [[worthy]] of note. The seated [[Vairochana]] [[Buddha]], 17.14 metres high, (pl- I), among other massive sculptures is a superb example of {{Wiki|Chinese}} carving dated to the beginning of 7th century A.D. Besides the rock cut [[caves]], the fossilized sand [[caves]] of Thousand [[Buddhas]], {{Wiki|Dunhuang}} (Gansu) contain unimaginably big straw built day sculptures installed in their [[shrines]] in there. The over-size {{Wiki|image}} of seated [[Buddha]] in wood in the main {{Wiki|cave}} (No. 096) measures 33 metres high and is within a seven storeyed pavilion with pent roofs, marking each storey and dated to 9th century AD. The wooden images are so well finished and painted in [[pleasing]] colours. The fine toranga arches with fiying [[apsaras]] and [[Gandharvas]] carrying garlands the maidens with floating garments around fully – blossomed [[lotus]] ceilings datable to early 5th-6th century AD., are some of the very attractive [[Indian]] style carvings at Longmen [[caves]] as well as painted ceilings of {{Wiki|Dunhuang}}. |

| − | The rock art of China is a true expansion of Indian art under the impact of Mahayana Buddhist spread, starting from first century AD. Later on with the unification of China under the Tang dynasty (AD. 618 - 907), the increasing interest in Indian Buddhist philosophy and works made China virtually a forte of later Buddhism, whereas in its land of origin, this religion suffered a setback. | + | The rock [[art]] of [[China]] is a true expansion of [[Indian]] [[art]] under the impact of [[Mahayana]] [[Buddhist]] spread, starting from first century AD. Later on with the unification of [[China]] under the {{Wiki|Tang dynasty}} (AD. 618 - 907), the {{Wiki|increasing}} [[interest]] in [[Indian]] [[Buddhist]] philosophy and works made [[China]] virtually a forte of later [[Buddhism]], whereas in its land of origin, this [[religion]] [[suffered]] a setback. |

[[File:EarthGoddess.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:EarthGoddess.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Even in later periods like Ming times (1366-1644) between Indian and Chinese art and architecture are traceable in the depictions such as vase and lotus scroll (purna - kumbha), among the white marble stone balustrades; the stately lions at the thresholds of the temple gateways (like the Pallava-Chola ones); the various memorial pagodas of brick-and stone built after the Bodhgaya-Sarnath examples as seen at Beijing (White Pagoda), the numerous ones at Dunhuang and Shaolin temple (pl- III) premises; the small seated bronze figures of Buddha and Bodhisattvas at the Fayuan Temple (Beijing are examples displaying close links between the mainland China and the Deccan Caves (Ajanta-Karle-Kanberi) on the one hand and the Guptan examples of Sanchi-Sarnath-Nalanda and Bodhgaya on the other. Strikingly enough, even during much later times also their impact continued. To cite an example the gold crown by the Ming Emperor Zu Yi Jun Wanli (1573-1620) reveals a Vishnuchakra (conch), at its crest, a symbol of royalty and it is quite fitting that Ming rulers who upheld Buddhism, and Taoism alike, held this conch in great esteem. A close semblance in architectural style can be found among the massive wooden pavilions and long halls on pillars with glazed tiled roofs in China and the medieval temples of wood in Kerala. The spacious high compounds, the well-planned gardens inside within the Forbidden City, Beijing impart a grandiose look to these architectural marvels whose colour, however, dominated the form. | + | Even in later periods like [[Ming]] times (1366-1644) between [[Indian]] and {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[art]] and architecture are traceable in the depictions such as vase and [[lotus]] scroll ([[purna]] - [[kumbha]]), among the white marble stone balustrades; the stately [[lions]] at the thresholds of the [[temple]] gateways (like the Pallava-Chola ones); the various memorial [[pagodas]] of brick-and stone built after the Bodhgaya-Sarnath examples as seen at {{Wiki|Beijing}} (White [[Pagoda]]), the numerous ones at {{Wiki|Dunhuang}} and [[Shaolin temple]] (pl- III) premises; the small seated bronze figures of [[Buddha]] and [[Bodhisattvas]] at the Fayuan [[Temple]] ({{Wiki|Beijing}} are examples displaying close links between the mainland [[China]] and the Deccan [[Caves]] (Ajanta-Karle-Kanberi) on the one hand and the Guptan examples of Sanchi-Sarnath-Nalanda and [[Bodhgaya]] on the other. Strikingly enough, even during much later times also their impact continued. To cite an example the {{Wiki|gold}} {{Wiki|crown}} by the [[Ming]] [[Emperor]] Zu Yi Jun Wanli (1573-1620) reveals a Vishnuchakra ([[conch]]), at its crest, a [[symbol]] of royalty and it is quite fitting that [[Ming]] rulers who upheld [[Buddhism]], and {{Wiki|Taoism}} alike, held this [[conch]] in great esteem. A close semblance in architectural style can be found among the massive wooden pavilions and long halls on pillars with glazed tiled roofs in [[China]] and the {{Wiki|medieval}} [[temples]] of wood in {{Wiki|Kerala}}. The spacious high compounds, the well-planned [[gardens]] inside within the Forbidden City, {{Wiki|Beijing}} impart a grandiose look to these architectural marvels whose {{Wiki|colour}}, however, dominated the [[form]]. |

| − | An interesting anecdote which nicely summarises the behavioural pattern of the Peoples of the World, both East and West was narrated to me. It appears God Almighty sitting in His heavenly abode, sported an idea that peoples of various countries and nationalities can approach him with their choicest desire only one and that too before the dawn. It is said that the first and earliest to reach were the Arabs who sought oil wealth. The next were Westerners (British and Europeans) who wanted intellect and tact. The third to reach at the exact time (just before dawn) were the Chinese and Japanese. Hearing that God had already given the wealth and intellect to others, they prayed for good muscles and determination to work. God gladly okayed. The last to reach were the Indians in heterogeneous groups unprepared even at the approach of sun rise, some still bathing, applying tilak singing or reciting on God and dressing up, etc., but none were ready with any united demand. The God just got up to leave His abode and hearing at the disputing and debating noisy Indians chided them to leave the place as He had nothing left to confer. Helpless and bemoaning they fell on the feet of the God praying Him to remain with them. So the Almighty in India – every village, every town, street and house and in growing numbers’ historically. While the Chinese – a dutiful, determined and disciplined people – perceive, and worship God through their hard work, love their country so much that one is amazed at the systematic development taking place in every sphere of life. Their pride in things ancient and regard for the antiquity and heritage is unparalleled. | + | An [[interesting]] anecdote which nicely summarises the behavioural pattern of the Peoples of the [[World]], both {{Wiki|East}} and {{Wiki|West}} was narrated to me. It appears [[God]] Almighty sitting in His [[heavenly]] [[abode]], sported an [[idea]] that peoples of various countries and nationalities can approach him with their choicest [[desire]] only one and that too before the dawn. It is said that the first and earliest to reach were the Arabs who sought oil [[wealth]]. The next were Westerners ({{Wiki|British}} and Europeans) who wanted {{Wiki|intellect}} and tact. The third to reach at the exact [[time]] (just before dawn) were the {{Wiki|Chinese}} and [[Japanese]]. [[Hearing]] that [[God]] had already given the [[wealth]] and {{Wiki|intellect}} to others, they prayed for good muscles and [[determination]] to work. [[God]] gladly okayed. The last to reach were the {{Wiki|Indians}} in heterogeneous groups unprepared even at the approach of {{Wiki|sun}} rise, some still bathing, applying tilak singing or reciting on [[God]] and dressing up, etc., but none were ready with any united demand. The [[God]] just got up to leave His [[abode]] and [[hearing]] at the disputing and [[debating]] noisy {{Wiki|Indians}} chided them to leave the place as He had [[nothing]] left to confer. Helpless and bemoaning they fell on the feet of the [[God]] praying Him to remain with them. So the Almighty in [[India]] – every village, every town, street and house and in growing numbers’ historically. While the {{Wiki|Chinese}} – a dutiful, determined and [[disciplined]] [[people]] – {{Wiki|perceive}}, and {{Wiki|worship}} [[God]] through their hard work, [[love]] their country so much that one is amazed at the systematic development taking place in every [[sphere]] of [[life]]. Their {{Wiki|pride}} in things {{Wiki|ancient}} and regard for the antiquity and heritage is unparalleled. |

| − | Gautama Buddha resting on the neighbouring hills, looking at the picturesque landscape around the beautiful city of Rajagriha, its many shrines and sanctuaries utters to Ananda. | + | [[Gautama Buddha]] resting on the neighbouring hills, looking at the picturesque landscape around the [[beautiful]] city of [[Rajagriha]], its many [[shrines]] and sanctuaries utters to [[Ananda]]. |

“Chitram Jambudvipam manoramam jivitam manushyanam” and bade a final farewell. | “Chitram Jambudvipam manoramam jivitam manushyanam” and bade a final farewell. | ||

| − | After seeing the most colourful Buddhist art treasures of China. I took leave with pleasant admiration saying to myself “Chitram - Chinadesam.” | + | After [[seeing]] the most colourful [[Buddhist art]] [[treasures]] of [[China]]. I took leave with [[pleasant]] admiration saying to myself “Chitram - Chinadesam.” |

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

[http://yabaluri.org/TRIVENI/CDWEB/buddhistchinaandsouthindiaoct88.htm yabaluri.org] | [http://yabaluri.org/TRIVENI/CDWEB/buddhistchinaandsouthindiaoct88.htm yabaluri.org] | ||

[[Category:Chinese Buddhism]] | [[Category:Chinese Buddhism]] | ||

[[Category:India]] | [[Category:India]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:38, 30 September 2013

By DR. I.K. SARMA

Nin hao, Indu = Hello! Welcome, Hindu; hen hao = excellent! that is haw an Indian is warmly greeted in China. You are! The snow skinned chubby faces and black-haired, fish-eyed youth of China are lovely to look at but all in uniforms – girls in white pants and short shirts and men in Mao’s coat, all blues with the red strip collars, monotonous in apparel and appearance. But there underlies a sincere love and affection to “Indus” in general a term that is sweet to utter and cherished by the Chinese–who instantly go deep in their thoughts on ancient Indian and Chinese cultural bonds. Yet Indians are rarely seen in China and the reverse is also true. Why these most ancient civilized Asians moulded in great eastern traditions and common cultural links remain somewhat isolated with each other?

I had the fortune of seeing this great country in October 1983 under an Indo-China Cultural Exchange Programme. My visit was mainly academic and to get a personal glimpse of the Chinese architectural and artistic wealth, mainly Buddhist affiliation. The historical and archaeological sites and Museums in and around Beijing, Gansu, Shanxi, Henan and Canton provinces of China were visited by me in a whirlwind tour, very ably arranged by the Central Cultural Relics Bureau, People’s Republic of China, Beijing.

Chinese chronicles mention about a gold statue of Buddha being brought to China in 122 B.C. (Western Han period). But it is fairly certain that China received Buddhism from India by the beginning of the Christian era (Eastern Han (25-200 A.D.) through the South-East Indian coast and Ceylon.

The three famous Chinese Travellers, Fa-hien (40-411), Yuan-Chwang (629-646), and It-Sing (671-695) have made enormous contribution to be the development of Buddhism in China and their numerous translation works on the Buddhist Sutras, Vinaya and Abhidharma, made China a reservoir of these treasures of Buddhist art, thought and literature. The foundations for such a prolific scholarly impetus must have been laid by a few centuries earlier to this trio. A Brahmi inscription dated to mid-third century A.D. from the ancient city of Sriparvata Vijayapuri in the Nagarjunakonda valley (Dt. Guntur, Andhra Pradesh), refers to the pilgrimage of some acharyas (scholars) to China and other countries for proselytizing the Buddhist order. These monks, together with other acharyas hailing from Kashmira, Gandhara and Ceylon, besides other places in India, worshipped the Bodhi Vriksha Prasada (Bodhi tree pavilion), extant on the Chula Dharmagiri Vihara monastrey at Nagarjunakonda. Nagarjunakonda’s Sriparvata is hallowed as the seat of Acharya Nagarjuna (2nd century A.D.), the founder of Madhyamika school of Mahayana Buddhism which spread all over China. At this place the Mahasamghika sects made headway and its principal schools like Chaityaka and Sailas propagated on meritorious acts such as the creation, decoration and worship of chaityas and eventually deified the Buddha and Bodhisattvas Mahayana Buddhism thus gained a high degree of popularity among the masses and crossed the Indian frontiers very swiftly. It is not one-sided. Chinese emperors greatly respected Indian Buddhist teachers and monks. There was a meaningful cultural exchange. Kanchipuram finds mention in a Chinese text dated to first century A.D. and called huang chao. It is said that Chinese emperors sent presents to the King of Fuang Cha in A.D. 1-6. Although initially Buddhism was humbled by the native Confucianism and was regarded as “Barbarian religion”, by the time of the Eastern Ts’ in (or Jin 317-420) and the Wei (386-551) dynasties’ firm foundations were laid for works of Buddhist art and Buddhism gained the status of a state religion by about 500 A.D. The translations undertaken by the Chinese traveller-trio were mostly based on the Madhyamika works expounded by Acharya Nagarjuna and elaborated later on by such great luminaries as Bhavaviveka and Kumarajiva (344-413). In particular, Huen Tsang studied the treaties of Abhidiharma with the monks at Dhanyakataka, the present Amaravati-Dharanikota in Dt. Guntur not far from Sri parvata Vijayapuri of Nagarjunakonda. Among the 657-Sanscrit works caused by him from India for translations, 15 were Mahasamghika works. In particular, this famous Chinese traveller makes mention of a Stupa, hundred feet high, built by Mauryan emperor at Kanchi and tradition assigns another Dharma soka Maharajavihara at Kaverippumpattinam (Dt. Thanjavur). A Buddhist temple specially meant for visiting Chinese monks existed during the time of Pallava King Narasimhavarman - II (695 - 722) at Nagapatinam. These were witness of a seaborne cultural exchange between Buddhist China-India and Ceylon. It might be noted that Bodhidharma, the well-known founder of Chan sect who lived at the ‘Sheaolin temple (Mount - Songshan, Province Henan) hailed from this part of India. So also, Dinnaga (5th century), the founder of medieval Nyaya school, hailed from Kanchi, a centre for Pali-Buddhism. It appears then that South East India with its long coastal line and convenient anchorages has been in contact with China and South East Asian centres during the early centuries of the Christian era.

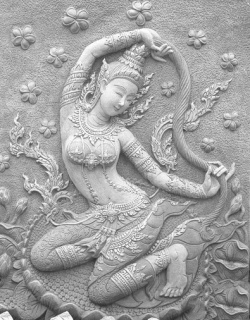

The consolidation of Buddhism led to the practice of making cliff grottoes and decorating them with wall paintings of Buddhist deities and legends. The most famous among these exist in North and West China. They are Kizil grottoes in Xin Jiang, the Mogo grottoes at Dunhuang (Gansu), Yuankang grottoes at Datong (Shanxi), Longmen caves at Louyang (Henan). In all these, as in Ajanta - Aurangabad, not only carved out figures, but sculptures in relief, extensively painted murals on the walls characterise the Indian impact and influences of Buddhist art. A variety of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas reflect great physical charm with all the Mahapurusha Lakshanas in a truly Indian style. The ten-thousand Buddha cave at Long man (pl- II), is worthy of note. The seated Vairochana Buddha, 17.14 metres high, (pl- I), among other massive sculptures is a superb example of Chinese carving dated to the beginning of 7th century A.D. Besides the rock cut caves, the fossilized sand caves of Thousand Buddhas, Dunhuang (Gansu) contain unimaginably big straw built day sculptures installed in their shrines in there. The over-size image of seated Buddha in wood in the main cave (No. 096) measures 33 metres high and is within a seven storeyed pavilion with pent roofs, marking each storey and dated to 9th century AD. The wooden images are so well finished and painted in pleasing colours. The fine toranga arches with fiying apsaras and Gandharvas carrying garlands the maidens with floating garments around fully – blossomed lotus ceilings datable to early 5th-6th century AD., are some of the very attractive Indian style carvings at Longmen caves as well as painted ceilings of Dunhuang.

The rock art of China is a true expansion of Indian art under the impact of Mahayana Buddhist spread, starting from first century AD. Later on with the unification of China under the Tang dynasty (AD. 618 - 907), the increasing interest in Indian Buddhist philosophy and works made China virtually a forte of later Buddhism, whereas in its land of origin, this religion suffered a setback.

Even in later periods like Ming times (1366-1644) between Indian and Chinese art and architecture are traceable in the depictions such as vase and lotus scroll (purna - kumbha), among the white marble stone balustrades; the stately lions at the thresholds of the temple gateways (like the Pallava-Chola ones); the various memorial pagodas of brick-and stone built after the Bodhgaya-Sarnath examples as seen at Beijing (White Pagoda), the numerous ones at Dunhuang and Shaolin temple (pl- III) premises; the small seated bronze figures of Buddha and Bodhisattvas at the Fayuan Temple (Beijing are examples displaying close links between the mainland China and the Deccan Caves (Ajanta-Karle-Kanberi) on the one hand and the Guptan examples of Sanchi-Sarnath-Nalanda and Bodhgaya on the other. Strikingly enough, even during much later times also their impact continued. To cite an example the gold crown by the Ming Emperor Zu Yi Jun Wanli (1573-1620) reveals a Vishnuchakra (conch), at its crest, a symbol of royalty and it is quite fitting that Ming rulers who upheld Buddhism, and Taoism alike, held this conch in great esteem. A close semblance in architectural style can be found among the massive wooden pavilions and long halls on pillars with glazed tiled roofs in China and the medieval temples of wood in Kerala. The spacious high compounds, the well-planned gardens inside within the Forbidden City, Beijing impart a grandiose look to these architectural marvels whose colour, however, dominated the form.

An interesting anecdote which nicely summarises the behavioural pattern of the Peoples of the World, both East and West was narrated to me. It appears God Almighty sitting in His heavenly abode, sported an idea that peoples of various countries and nationalities can approach him with their choicest desire only one and that too before the dawn. It is said that the first and earliest to reach were the Arabs who sought oil wealth. The next were Westerners (British and Europeans) who wanted intellect and tact. The third to reach at the exact time (just before dawn) were the Chinese and Japanese. Hearing that God had already given the wealth and intellect to others, they prayed for good muscles and determination to work. God gladly okayed. The last to reach were the Indians in heterogeneous groups unprepared even at the approach of sun rise, some still bathing, applying tilak singing or reciting on God and dressing up, etc., but none were ready with any united demand. The God just got up to leave His abode and hearing at the disputing and debating noisy Indians chided them to leave the place as He had nothing left to confer. Helpless and bemoaning they fell on the feet of the God praying Him to remain with them. So the Almighty in India – every village, every town, street and house and in growing numbers’ historically. While the Chinese – a dutiful, determined and disciplined people – perceive, and worship God through their hard work, love their country so much that one is amazed at the systematic development taking place in every sphere of life. Their pride in things ancient and regard for the antiquity and heritage is unparalleled.

Gautama Buddha resting on the neighbouring hills, looking at the picturesque landscape around the beautiful city of Rajagriha, its many shrines and sanctuaries utters to Ananda.

“Chitram Jambudvipam manoramam jivitam manushyanam” and bade a final farewell.

After seeing the most colourful Buddhist art treasures of China. I took leave with pleasant admiration saying to myself “Chitram - Chinadesam.”