Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana Buddhism

大乗仏教 ( Jpn Daijo-bukkyo)

Buddhism of the Great Vehicle. The Sanskrit maha means great, and yana, vehicle. One of the two major divisions of the Buddhist teachings, Mahayana and Hinayana. Mahayana emphasizes altruistic practice—called the bodhisattva practice—as a means to attain enlightenment for oneself and help others attain it as well. In contrast, Hinayana Buddhism (Buddhism of the Lesser Vehicle, hina meaning lower or lesser), as viewed by Mahayanists, aims primarily at personal awakening, or attaining the state of arhat through personal discipline and practice. After Shakyamuni's death, the Buddhist Order experienced several schisms, and eventually eighteen or twenty schools formed, each of which developed its own doctrinal interpretation of the sutras.

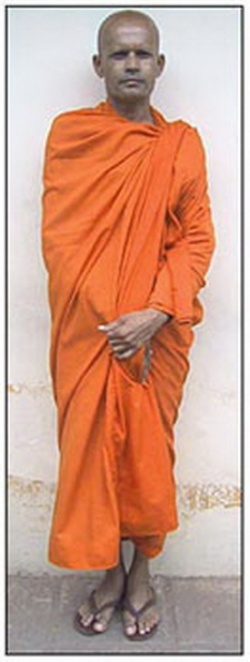

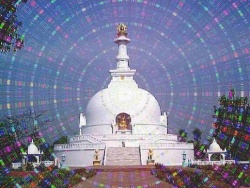

As time passed, the monks of these schools tended toward monastic lifestyles that were increasingly reclusive, devoting themselves to the practice of precepts and the writing of doctrinal exegeses. This tendency was criticized by those who felt the monks were too conservative, rigid, and elitist, believing they had lost the Buddha's original spirit of working among the people for their salvation. Around the end of the first century B.C.E. and the beginning of the first century C.E., a new Buddhist movement arose. Its adherents called it Mahayana, indicating a teaching that can serve as a vehicle to carry a great number of people to a level of enlightenment equal to that of the Buddha. They criticized the older conservative schools for seeking only personal enlightenment, derisively calling them Hinayana (Lesser Vehicle) indicating a teaching capable of carrying only a select few to the lesser objective of arhat. According to one opinion, the Mahayana movement may have originated with the popular practice of stupa worship—revering the relics of the Buddha— that spread throughout India during the reign of King Ashoka. In any event, it seems to have arisen at least in part as a popular reform move-ment involving laypersons as well as clergy.

See also; Hinayana Buddhism.

THE MAHAYANA

CHAPTER

PAGE

XVI MAIN FEATURES OF THE MAHAYANA 3

XVII BODHISATTVAS 7

XVIII THE BUDDHAS of MAHAYANISM 26

XIX MAHAYANIST METAPHYSICS 36

XX MAHAYANIST SCRIPTURES 47

XXI CHRONOLOGY OF THE MAHAYANA 63

XXII FROM KANISHKA TO VASUBANDHU 76

XXIII INDIAN BUDDHISM AS SEEN BY THE CHINESE PILGRIMS 90

XXIV DECADENCE OF BUDDHISM IN INDIA 107

CHAPTER XVI

MAIN FEATURES OF THE MAHAYANA

The obscurest period in the history of Buddhism is that which follows the reign of Asoka, but the enquirer cannot grope for long in these dark ages without stumbling upon the word Mahayana. This is the name given to a movement which in its various phases may be regarded as a philosophical school, a sect and a church, and though it is not always easy to define its relationship to other schools and sects it certainly became a prominent aspe [4] ct of Buddhism in India about the beginning of our era besides achieving enduring triumphs in the Far East. The word[1] signifies Great Vehicle or Carriage, that is a means of conveyance to salvation, and is contrasted with Hinayana, the Little Vehicle, a name bestowed on the more conservative party though not willingly accepted by them. The simplest description of the two Vehicles is that given by the Chinese traveller I-Ching (635-713 A.D.) who saw them both as living realities in India. He says[2] "Those who worship Bodhisattvas and read Mahayana Sutras are called Mahayanists, while those who do not do this are called Hinayanists." In other words, the Mahayanists have scriptures of their own, not included in the Hinayanist Canon and adore superhuman beings in the stage of existence immediately below Buddhahood and practically differing little from Indian deities. Many characteristics could be added to I-Ching's description but they might not prove universally true of the Mahayana nor entirely absent from the Hinayana, for however divergent the two Vehicles may have become when separated geographically, for instance in Ceylon and Japan, it is clear that when they were in contact, as in India and China, the distinction was not always sharp. But in general the Mahayana was more popular, not in the sense of being simpler, for parts of its teaching were exceedingly abstruse, but in the sense of striving to invent or include doctrines agreeable to the masses. It was less monastic than the older Buddhism, and more emotional; warmer in charity, more personal in devotion, more ornate in art, literature and ritual, more disposed to evolution and development, whereas the Hinayana was conservative and rigid, secluded in its cloisters and open to the plausible if unjust accusation of selfishness. The two sections are sometimes described as northern and southern Buddhism, but except as a rough description of their distribution at the present day, this distinction is not accurate, for the Mahayana penetrated to Java, while the Hinayana reached Central Asia and China. But it is true that the development of the Mahayana was due to influences prevalent in northern India and not equally prevalent in the South. The terms Pali and Sanskrit Buddhism are convenient and as accurate as can be expected of any nomenclature covering so large a field.

Though European writers usually talk of two Yânas or Vehicles—the great and the little—and though this is clearly the important distinction for historical purposes, yet Indian and Chinese Buddhists frequently enumerate three. These are the Śrâvakayâna, the vehicle of the ordinary Bhikshu who hopes to become an Arhat, the Pratyekabuddhayâna for the rare beings who are able to become Buddhas but do not preach the law to others, and in contrast to both of these the Mahayana or vehicle of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. As a rule these three Vehicles are not regarded as hostile or even incompatible. Thus the Lotus sutra,[3] maintains that there is really but one vehicle though by a wise concession to human weakness the Buddha lets it appear that there are three to suit divers tastes. And the Mahayana is not a single vehicle but rather a train comprising many carriages of different classes. It has an unfortunate but distinct later phase known in Sanskrit as Mantrayâna and Vajrayâna but generally described by Europeans as Tantrism. This phase took some of the worst features in Hinduism, [5]such as spells, charms, and the worship of goddesses, and with misplaced ingenuity fitted them into Buddhism. I shall treat of it in a subsequent chapter, for it is chronologically late. The silence of Hsüan Chuang and I-Ching implies that in the seventh century it was not a noticeable aspect of Indian Buddhism.

Although the record of the Mahayana in literature and art is clear and even brilliant, it is not easy either to trace its rise or connect its development with other events in India. Its annals are an interminable list of names and doctrines, but bring before us few living personalities and hence are dull. They are like a record of the Christian Church's fight against Arians, Monophysites and Nestorians with all the great figures of Byzantine history omitted or called in question. Hence I fear that my readers (if I have any) may find these chapters repellent, a mist of hypotheses and a catalogue of ancient paradoxes. I can only urge that if the history of the Mahayana is uncertain, its teaching fanciful and its scriptures tedious, yet it has been a force of the first magnitude in the secular history and art of China, Japan and Tibet and even to-day the most metaphysical of its sacred books, the Diamond Cutter, has probably more readers than Kant and Hegel.

Since the early history of the Mahayana is a matter for argument rather than precise statement, it will perhaps be best to begin with some account of its doctrines and literature and proceed afterwards to chronology. I may, however, mention that general tradition connects it with King Kanishka and asserts that the great doctors Aśvaghosha and Nâgârjuna lived in and immediately after his reign. The attitude of Kanishka and of the Council which he summoned towards the Mahayana is far from clear and I shall say something about this difficult subject below. Unfortunately his date is not beyond dispute for while a considerable consensus of opinion fixes his accession at about 78 A.D., some scholars place it earlier and others in the second century A.D.[4] Apart from this, it appears established that the Sukhâvatî-vyûha which is definitely Mahayanist was translated into Chinese between 147 and 186 A.D. We may assume that it was then already well known and had been composed some time before, so that, whatever Kanishka's date may [6]have been, Mahayanist doctrines must have been in existence about the time of the Christian era, and perhaps considerably earlier. Naturally no one date like a reign or a council can be selected to mark the beginning of a great school. Such a body of doctrine must have existed piecemeal and unauthorized before it was collected and recognized and some tenets are older than others. Enlarging I-Ching's definition we may find in the Mahayana seven lines of thought or practice. All are not found in all sects and some are shared with the Hinayana but probably none are found fully developed outside the Mahayana. Many of them have parallels in the contemporary phases of Hinduism.

1. A belief in Bodhisattvas and in the power of human beings to become Bodhisattvas.

2. A code of altruistic ethics which teaches that everyone must do good in the interest of the whole world and make over to others any merit he may acquire by his virtues. The aim of the religious life is to become a Bodhisattva, not to become an Arhat.

3. A doctrine that Buddhas are supernatural beings, distributed through infinite space and time, and innumerable. In the language of later theology a Buddha has three bodies and still later there is a group of five Buddhas.

4. Various systems of idealist metaphysics, which tend to regard the Buddha essence or Nirvana much as Brahman is regarded in the Vedanta.

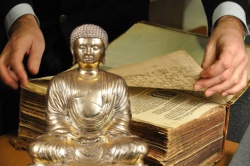

5. A canon composed in Sanskrit and apparently later than the Pali Canon.

6. Habitual worship of images and elaboration of ritual. There is a dangerous tendency to rely on formulæ and charms.

7. A special doctrine of salvation by faith in a Buddha, usually Amitâbha, and invocation of his name. Mahayanism can exist without this doctrine but it is tolerated by most sects and considered essential by some.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Sanskrit, Mahâyâna; Chinese, Ta Ch'êng (pronounced Tai Shêng in many southern provinces); Japanese, Dai-jō Tibetan, Theg-pa-chen-po; Mongolian, Yäkä-külgän; Sanskrit, Hînayâna; Chinese, Hsiao-Ch'êng; Japanese, Shō-jō Tibetan, Theg-dman; Mongolian Ütśükän-külgän. In Sanskrit the synonyms agrayâna and uttama-yâna are also found.

[2] Record of Buddhist practices. Transl. Takakusu, 1896, p. 14. Hsüan Chuang seems to have thought that acceptance of the Yogâcâryabhûmi (Nanjio, 1170) was essential for a Mahayanist. See his life, transl. by Beal, p. 39, transl. by Julien, p. 50.

[3] Saddharma-Puṇḍarîka, chap. III. For brevity, I usually cite this work by the title of The Lotus.

[4] The date 58 B.C. has probably few supporters among scholars now, especially after Marshall's discoveries.

CHAPTER XVII

BODHISATTVAS

Let us now consider these doctrines and take first the worship of Bodhisattvas. This word means one whose essence is knowledge but is used in the technical sense of a being who is in process of obtaining but has not yet obtained Buddhahood. The Pali Canon shows little interest in the personality of Bodhisattvas and regards them simply as the preliminary or larval form of a Buddha, either Śâkyamuni[5] or some of his predecessors. It was incredible that a being so superior to ordinary humanity as a Buddha should be suddenly produced in a human family nor could he be regarded as an incarnation in the strict sense. But it was both logical and edifying to suppose that he was the product of a long evolution of virtue, of good deeds and noble resolutions extending through countless ages and culminating in a being superior to the Devas. Such a being awaited in the Tushita heaven the time fixed for his appearance on earth as a Buddha and his birth was accompanied by marvels. But though the Pali Canon thus recognizes the Bodhisattva as a type which, if rare, yet makes its appearance at certain intervals, it leaves the matter there. It is not suggested that saints should try to become Bodhisattvas and Buddhas, or that Bodhisattvas can be helpers of mankind.[6] But both these trains of thought are natural developments of the older ideas and soon made themselves prominent. It is a characteristic doctrine of Mahayanism that men can try and should try to become Bodhisattvas.

In the Pali Canon we hear of Arhats, Pacceka Buddhas, and perfect Buddhas. For all three the ultimate goal is the same, namely Nirvana, but a Pacceka Buddha is greater than an Arhat, because he has greater intellectual powers though he is not omniscient, and a perfect Buddha is greater still, partly because he is omniscient and partly because he saves others. But if we admit that the career of the Buddha is better and nobler, and also that it is, as the Introduction to the Jâtaka recounts, simply the result of an earnest resolution to school himself and help others, kept firmly through the long chain of existences, there is nothing illogical or presumptuous in making our goal not the quest of personal salvation, but the attainment of Bodhisattvaship, that is the state of those who may aspire to become Buddhas. In fact the Arhat, engrossed in his own salvation, is excused only by his humility and is open to the charge of selfish desire, since the passion for Nirvana is an ambition like any other and the quest for salvation can be best followed by devoting oneself entirely to others. But though my object here is to render intelligible the Mahayanist point of view including its objections to Hinayanism, I must defend the latter from the accusation of selfishness. The vigorous and authoritative character of Gotama led him to regard all mankind as patients requiring treatment and to emphasize the truth that they could cure themselves if they would try. But the Buddhism of the Pali Canon does not ignore the duties of loving and instructing others;[7] it merely insists on man's power to save himself if properly instructed and bids him do it at once: "sell all that thou hast and follow me." And the Mahayana, if less self-centred, has also less self-reliance, and self-discipline. It is more human and charitable, but also more easygoing: it teaches the believer to lean on external supports which if well chosen may be a help, but if trusted without discrimination become paralyzing abuses. And if we look at the abuses of both systems the fossilized monk of the Hinayana will compare favourably [9] with the tantric adept. It was to the corruptions of the Mahayana rather than of the Hinayana that the decay of Buddhism in India was due.

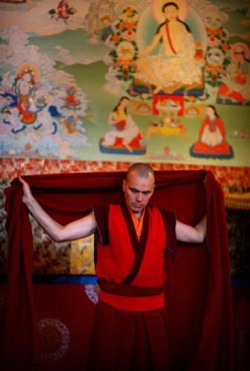

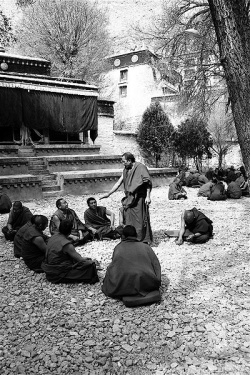

The career of the Bodhisattva was early divided into stages (bhûmi) each marked by the acquisition of some virtue in his triumphant course. The stages are variously reckoned as five, seven and ten. The Mahâvastu,[8] which is the earliest work where the progress is described, enumerates ten without distinguishing them very clearly. Later writers commonly look at the Bodhisattva's task from the humbler point of view of the beginner who wishes to learn the initiatory stages. For them the Bodhisattva is primarily not a supernatural being or even a saint but simply a religious person who wishes to perform the duties and enjoy the privileges of the Church to the full, much like a communicant in the language of contemporary Christianity. We have a manual for those who would follow this path, in the Bodhicaryâvatâra of Śântideva, which in its humility, sweetness and fervent piety has been rightly compared with the De Imitatione Christi. In many respects the virtues of the Bodhisattva are those of the Arhat. His will must be strenuous and concentrated; he must cultivate the strictest morality, patience, energy, meditation and knowledge. But he is also a devotee, a bhakta: he adores all the Buddhas of the past, present and future as well as sundry superhuman Bodhisattvas, and he confesses his sins, not after the fashion of the Pâtimokkha, but by accusing himself before these heavenly Protectors and vowing to sin no more.

Śântideva lived in the seventh century[9] but tells us that he follows the scriptures and has nothing new to say. This seems to be true for, though his book being a manual of devotion presents its subject-matter in a dogmatic form, its main ideas are stated and even elaborated in the Lotus. Not only are eminent figures in the Church, such as Sâriputra and Ânanda, there designated as future Buddhas, but the same dignity is predicted wholesale for five hundred and again for two thousand [10]monks while in Chapter x is sketched the course to be followed by "young men or young ladies of good family" who wish to become Bodhisattvas.[10] The chief difference is that the Bodhicaryâvatâra portrays a more spiritual life, it speaks more of devotion, less of the million shapes that compose the heavenly host: more of love and wisdom, less of the merits of reading particular sûtras. While rendering to it and the faith that produced it all honour, we must remember that it is typical of the Mahayana only in the sense that the De Imitatione Christi is typical of Roman Catholicism, for both faiths have other sides.

Śântideva's Bodhisattva, when conceiving the thought of Bodhi or eventual supreme enlightenment to be obtained, it may be, only after numberless births, feels first a sympathetic joy in the good actions of all living beings. He addresses to the Buddhas a prayer which is not a mere act of commemoration, but a request to preach the law and to defer their entrance into Nirvana. He then makes over to others whatever merit he may possess or acquire and offers himself and all his possessions, moral and material, as a sacrifice for the salvation of all beings. This on the one hand does not much exceed the limits of dânam or the virtue of giving as practised by Śâkyamuni in previous births according to the Pali scriptures, but on the other it contains in embryo the doctrine of vicarious merit and salvation through a saviour. The older tradition admits that the future Buddha (e.g. in the Vessantara birth-story) gives all that is asked from him including life, wife and children. To consider the surrender and transfer of merit (pattidâna in Pali) as parallel is a natural though perhaps false analogy. But the transfer of Karma is not altogether foreign to Brahmanic thought, for it is held that a wife may share in her husband's Karma nor is it wholly unknown to Sinhalese Buddhism.[11] After thus deliberately rejecting all personal success and selfish aims, the neophyte makes a vow (praṇidhâna) to acquire enlightenment for the good of all beings and not to swerve from the rules of life and faith requisite for this end. He is then a "son [11]of Buddha," a phrase which is merely a natural metaphor for saying that he is one of the household of faith[12] but still paves the way to later ideas which make the celestial Bodhisattva an emanation or spiritual son of a celestial Buddha.

Asanga gives[13] a more technical and scholastic description of the ten bhûmis or stages which mark the Bodhisattva's progress towards complete enlightenment and culminate in a phase bearing the remarkable but ancient name of Dharmamegha known also to the Yoga philosophy. The other stages are called: muditâ (joyful): vimalâ (immaculate): prabhâkarî (light giving): arcismatî (radiant): durjaya (hard to gain): abhimukhî (facing, because it faces both transmigration and Nirvana): dûramgamâ (far-going): acalâ (immovable): sâdhumatî (good minded).

The incarnate Buddhas and Bodhisattvas of Tibet are a travesty of the Mahayana which on Indian soil adhered to the sound doctrine that saints are known by their achievements as men and cannot be selected among infant prodigies.[14] It was the general though not universal opinion that one who had entered on the career of a Bodhisattva could not fall so low as to be reborn in any state of punishment, but the spirit of humility and self-effacement which has always marked the Buddhist ideal tended to represent his triumph as incalculably distant. Meanwhile, although in the whirl of births he was on the upward grade, he yet had his ups and downs and there is no evidence that Indian or Far Eastern Buddhists arrogated to themselves special claims and powers on the ground that they were well advanced in the career of Buddhahood. The vow to suppress self and follow the light not only in this life but in all future births contains an element of faith or fantasy, but has any religion formed a nobler or even equivalent picture of the soul's destiny or built a better staircase from the world of men to the immeasurable spheres of the superhuman?

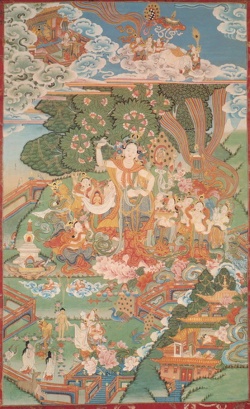

One aspect of the story of Sâkyamuni and his antecedent births thus led to the idea that all may become Buddhas. An [12] equally natural development in another direction created celestial and superhuman Bodhisattvas. The Hinayana held that Gotama, before his last birth, dwelt in the Tushita heaven enjoying the power and splendour of an Indian god and it looked forward to the advent of Maitreya. But it admitted no other Bodhisattvas, a consequence apparently of the doctrine that there can only be one Buddha at a time. But the luxuriant fancy of India, which loves to multiply divinities, soon broke through this restriction and fashioned for itself beautiful images of benevolent beings who refuse the bliss of Nirvana that they may alleviate the sufferings of others.[15] So far as we can judge, the figures of these Bodhisattvas took shape just about the same time that the personalities of Vishnu and Śiva were acquiring consistency. The impulse in both cases is the same, namely the desire to express in a form accessible to human prayer and sympathetic to human emotion the forces which rule the universe. But in this work of portraiture the Buddhists laid more emphasis on moral and spiritual law than did the Brahmans: they isolated in personification qualities not found isolated in nature. Śiva is the law of change, of death and rebirth, with all the riot of slaughter and priapism which it entails: Vishnu is the protector and preserver, the type of good energy warring against evil, but the unity of the figure is smothered by mythology and broken up into various incarnations. But Avalokita and Mañjuśrî, though they had not such strong roots in Indian humanity as Śiva and Vishnu, are genii of purer and brighter presence. They are the personifications of kindness and knowledge. Though manifold in shape, they have little to do with mythology, and are analogous to the archangels of Christian and Jewish tradition and to the Amesha Spentas of Zoroastrianism. With these latter they may have some historical connection, for Persian ideas may well have influenced Buddhism about the time of the Christian era. However difficult it may be to prove the foreign origin of Bodhisattvas, few of them have a clear origin in India and all of them [13] are much better known in Central Asia and China. But they are represented with the appearance and attributes of Indian Devas, as is natural, since even in the Pali Canon Devas form the Buddha's retinue. The early Buddhists considered that these spirits, whether called Bodhisattvas or Devas, had attained their high position in the same way as Śâkyamuni himself, that is by the practice of moral and intellectual virtues through countless existences, but subsequently they came to be regarded as emanations or sons of superhuman Buddhas. Thus the Kâraṇḍa-vyûha relates how the original Âdi-Buddha produced Avalokita by meditation and how he in his turn produced the universe with its gods.

Millions of unnamed Bodhisattvas are freely mentioned and even in the older books copious lists of names are found,[16] but two, Avalokita and Mañjuśrî, tower above the rest, among whom only few have a definite personality. The tantric school counts eight of the first rank. Maitreya (who does not stand on the same footing as the others), Samantabhadra, Mahâsthâna-prâpta and above all Kshitigarbha, have some importance, especially in China and Japan.

Avalokita[17] in many forms and in many ages has been one of the principal deities of Asia but his origin is obscure. His main attributes are plain. He is the personification of divine mercy and pity but even the meaning of his name is doubtful. In its full form it is Avalokiteśvara, often rendered the Lord who looks down (from heaven). This is an appropriate title for the God of Mercy, but the obvious meaning of the participle avalokita in Sanskrit is passive, the Lord who is looked at. Kern[18] thinks it may mean the Lord who is everywhere visible as a very present help in trouble, or else the Lord of View, like the epithet Dṛishtiguru applied to Śiva. Another form of the name is Lokeśvara or Lord of the world and this suggests that avalokita may be a synonym of loka, meaning the visible universe. It has also been suggested that the name may refer to the small image of Amitâbha which is set in his diadem and thus looks down on him. But such small images set in the head of a larger figure are not distinctive of Avalokita: they are found [14] in other Buddhist statues and paintings and also outside India, for instance at Palmyra. The Tibetan translation of the name[19] means he who sees with bright eyes. Hsüan Chuang's rendering Kwan-tzǔ-tsai[20] expresses the same idea, but the more usual Chinese translation Kuan-yin or Kuan-shih-yin, the deity who looks upon voices or the region of voices, seems to imply a verbal misunderstanding. For the use of Yin or voice makes us suspect that the translator identified the last part of Avalokiteśvara not with Îśvara lord but with svara sound.[21]

Avalokiteśvara is unknown to the Pali Canon and the Milinda Pañha. So far as I can discover he is not mentioned in the Divyâvadâna, Jâtakamâlâ or any work attributed to Aśvaghosha. His name does not occur in the Lalita-vistara but a list of Bodhisattvas in its introductory chapter includes Mahâkaruṇâcandin, suggesting Mahâkaruna, the Great Compassionate, which is one of his epithets. In the Lotus[22] he is placed second in the introductory list of Bodhisattvas after Mañjuśrî. But Chapter XXIV, which is probably a later addition, is dedicated to his praises as Samantamukha, he who looks every way or the omnipresent. In this section his character as the all-merciful saviour is fully developed. He saves those who call on him from shipwreck, and execution, from robbers and all violence and distress. He saves too from moral evils, such as passion, hatred and folly. He grants children to women who worship him. This power, which is commonly exercised by female deities, is worth remarking as a hint of his subsequent transformation into a goddess. For the better achievement of his merciful deeds, he assumes all manner of forms, and appears in the guise of a Buddha, a Bodhisattva, a Hindu deity, a goblin, or a Brahman and in fact in any shape. This chapter was translated into Chinese before 417 A.D. and therefore can hardly be later than 350. He is also mentioned in the Sukhâvatî-vyûha. [15] The records of the Chinese pilgrims Fa-Hsien and Hsüan Chuang[23] indicate that his worship prevailed in India from the fourth till the seventh century and we are perhaps justified in dating its beginnings at least two centuries earlier. But the absence of any mention of it in the writings of Aśvaghosha is remarkable.[24]

Avalokita is connected with a mountain called Potala or Potalaka. The name is borne by the palace of the Grand Lama at Lhassa and by another Lamaistic establishment at Jehol in north China. It reappears in the sacred island of P´u-t´o near Ningpo. In all these cases the name of Avalokita's Indian residence has been transferred to foreign shrines. In India there were at least two places called Potala or Potalaka—one at the mouth of the Indus and one in the south. No certain connection has been traced between the former and the Bodhisattva but in the seventh century the latter was regarded as his abode. Our information about it comes mainly from Hsüan Chuang[25] who describes it when speaking of the Malakuta country and as near the Mo-lo-ya (Malaya) mountain. But apparently he did not visit it and this makes it probable that it was not a religious centre but a mountain in the south of which Buddhists in the north wrote with little precision.[26] There is no evidence that Avalokita was first worshipped on this Potalaka, though he is often associated with mountains such as Kapota in Magadha and Valavatî in Katâha.[27] In fact the connection of Potala with Avalokita remains a mystery.

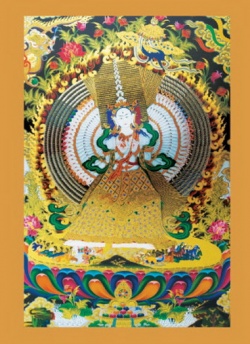

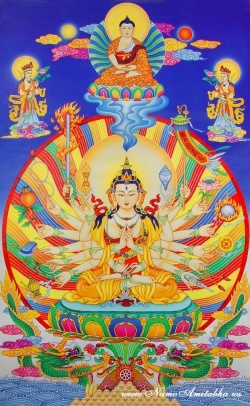

Avalokita has, like most Bodhisattvas, many names. Among the principal are Mahâkaruna, the Great Compassionate one, Lokanâtha or Lokeśvara, the Lord of the world, and Padmapâni, or lotus-handed. This last refers to his appearance as portrayed in statues and miniatures. In the older works of art his figure [16] is human, without redundant limbs, and represents a youth in the costume of an Indian prince with a high jewelled chignon, or sometimes a crown. The head-dress is usually surmounted by a small figure of Amitâbha. His right hand is extended in the position known as the gesture of charity.[28] In his left he carries a red lotus and he often stands on a larger blossom. His complexion is white or red. Sometimes he has four arms and in later images a great number. He then carries besides the lotus such objects as a book, a rosary and a jug of nectar.[29]

The images with many eyes and arms seem an attempt to represent him as looking after the unhappy in all quarters and stretching out his hands in help.[30] It is doubtful if the Bodhisattvas of the Gandhara sculptures, though approaching the type of Avalokita, represent him rather than any other, but nearly all the Buddhist sites of India contain representations of him which date from the early centuries of our era[31] and others are preserved in the miniatures of manuscripts.[32]

He is not a mere adaptation of any one Hindu god. Some of his attributes are also those of Brahmâ. Though in some late texts he is said to have evolved the world from himself, his characteristic function is not to create but, like Vishnu, to save and like Vishnu he holds a lotus. But also he has the title of Îśvara, which is specially applied to Śiva. Thus he does not issue from any local cult and has no single mythological pedigree but is the idea of divine compassion represented with such materials as the art and mythology of the day offered.

He is often accompanied by a female figure Târâ.[33] In the tantric period she is recognized as his spouse and her images, common in northern India from the seventh century onwards, [17] show that she was adored as a female Bodhisattva. In Tibet Târâ is an important deity who assumes many forms and even before the tantric influence had become prominent she seems to have been associated with Avalokita. In the Dharmasangraha she is named as one of the four Devîs, and she is mentioned twice under the name of To-lo Pu-sa by Hsüan Chuang, who saw a statue of her in Vaisali and another at Tiladhaka in Magadha. This last stood on the right of a gigantic figure of Buddha, Avalokita being on his left.[34]

Hsüan Chuang distinguishes To-lo (Târâ) and Kuan-tzǔ-tsai. The latter under the name of Kuan-yin or Kwannon has become the most popular goddess of China and Japan, but is apparently a form of Avalokita. The god in his desire to help mankind assumes many shapes and, among these, divine womanhood has by the suffrage of millions been judged the most appropriate. But Târâ was not originally the same as Kuan-yin, though the fact that she accompanies Avalokita and shares his attributes may have made it easier to think of him in female form.[35]

The circumstances in which Avalokita became a goddess are obscure. The Indian images of him are not feminine, although his sex is hardly noticed before the tantric period. He is not a male deity like Krishna, but a strong, bright spirit and like the Christian archangels above sexual distinctions. No female form of him is reported from Tibet and this confirms the idea that none was known in India,[36] and that the change was made in China. It was probably facilitated by the worship of Târâ and of Hâritî, an ogress who was converted by the Buddha and is frequently represented in her regenerate state caressing a child. [18] She is mentioned by Hsüan Chuang and by I-Ching who adds that her image was already known in China. The Chinese also worshipped a native goddess called T'ien-hou or T'ou-mu. Kuan-yin was also identified with an ancient Chinese heroine called Miao-shên.[37] This is parallel to the legend of Ti-tsang (Kshitigarbha) who, though a male Bodhisattva, was a virtuous maiden in two of his previous existences. Evidently Chinese religious sentiment required a Madonna and it is not unnatural if the god of mercy, who was reputed to assume many shapes and to give sons to the childless, came to be thought of chiefly in a feminine form. The artists of the T'ang dynasty usually represented Avalokita as a youth with a slight moustache and the evidence as to early female figures does not seem to me strong,[38] though a priori I see no reason for doubting their existence. In 1102 a Chinese monk named P'u-ming published a romantic legend of Kuan-yin's earthly life which helped to popularize her worship. In this and many other cases the later developments of Buddhism are due to Chinese fancy and have no connection with Indian tradition.

Târâ is a goddess of north India, Nepal and the Lamaist Church and almost unknown in China and Japan. Her name means she who causes to cross, that is who saves, life and its troubles being by a common metaphor described as a sea. Târâ also means a star and in Puranic mythology is the name given to the mother of Buddha, the planet Mercury. Whether the name was first used by Buddhists or Brahmans is unknown, but after the seventh century there was a decided tendency to give Târâ the epithets bestowed on the Śaktis of Śiva and assimilate her to those goddesses. Thus in the list of her 108 names[39] she is described among other more amiable attributes as [19] terrible, furious, the slayer of evil beings, the destroyer, and Kâlî: also as carrying skulls and being the mother of the Vedas. Here we have if not the borrowing by Buddhists of a Śaiva deity, at least the grafting of Śaiva conceptions on a Bodhisattva.

The second great Bodhisattva Mañjuśrî[40] has other similar names, such as Mañjunâtha and Mañjughosha, the word Mañju meaning sweet or pleasant. He is also Vagîśvara, the Lord of Speech, and Kumârabhûta, the Prince, which possibly implies that he is the Buddha's eldest son, charged with the government under his direction. He has much the same literary history as Avalokita, not being mentioned in the Pali Canon nor in the earlier Sanskrit works such as the Lalita-vistara and Divyâvadâna. But his name occurs in the Sukhâvatî-vyûha: he is the principal interlocutor in the Lankâvatâra sûtra and is extolled in the Ratna-karaṇḍaka-vyûha-sûtra.[41] In the greater part of the Lotus he is the principal Bodhisattva and instructs Maitreya, because, though his youth is eternal, he has known many Buddhas through innumerable ages. The Lotus[42] also recounts how he visited the depths of the sea and converted the inhabitants thereof and how the Lord taught him what are the duties of a Bodhisattva after the Buddha has entered finally into Nirvana. As a rule he has no consort and appears as a male Athene, all intellect and chastity, but sometimes Lakshmî or Sarasvatî or both are described as his consorts.[43]

His worship prevailed not only in India but in Nepal, Tibet, China, Japan and Java. Fa-Hsien states that he was honoured in Central India, and Hsüan Chuang that there were stupas dedicated to him at Muttra.[44] He is also said to have been incarnate in Atîsa, the Tibetan reformer, and in Vairocana who introduced Buddhism to Khotan, but, great as is his benevolence, he is not so much the helper of human beings, which is Avalokita's special function, as the personification of thought,[20] knowledge, and meditation. It is for this that he has in his hands the sword of knowledge and a book. A beautiful figure from Java bearing these emblems is in the Berlin Museum.[45] Miniatures represent him as of a yellow colour with the hands (when they do not carry emblems) set in the position known as teaching the law.[46] Other signs which distinguish his images are the blue lotus and the lion on which he sits.

An interesting fact about Mañjuśrî is his association with China,[47] not only in Chinese but in late Indian legends. The mountain Wu-t'ai-shan in the province of Shan-si is sacred to him and is covered with temples erected in his honour.[48] The name (mountain of five terraces) is rendered in Sanskrit as Pancaśîrsha, or Pancaśikha, and occurs both in the Svayambhû Purâṇa and in the text appended to miniatures representing Mañjuśrî. The principal temple is said to have been erected between 471 and 500 A.D. I have not seen any statement that the locality was sacred in pre-Buddhist times, but it was probably regarded as the haunt of deities, one of whom—perhaps some spirit of divination—was identified with the wise Mañjuśrî. It is possible that during the various inroads of Græco-Bactrians, Yüeh-Chih, and other Central Asian tribes into India, Mañjuśrî was somehow imported into the pantheon of the Mahayana from China or Central Asia, and he has, especially in the earlier descriptions, a certain pure and abstract quality which recalls the Amesha-Spentas of [21] Persia. But still his attributes are Indian, and there is little positive evidence of a foreign origin. I-Ching is the first to tell us that the Hindus believed he came from China.[49] Hsüan Chuang does not mention this belief, and probably did not hear of it, for it is an interesting detail which no one writing for a Chinese audience would have omitted. We may therefore suppose that the idea arose in India about 650 A.D. By that date the temples of Wu-t'ai-Shan would have had time to become celebrated, and the visits paid to India by distinguished Chinese Buddhists would be likely to create the impression that China was a centre of the faith and frequented by Bodhisattvas.[50] We hear that Vajrabodhi (about 700) and Prajña (782) both went to China to adore Mañjuśrî. In 824 a Tibetan envoy arrived at the Chinese Court to ask for an image of Mañjuśrî, and later the Grand Lamas officially recognized that he was incarnate in the Emperor.[51] Another legend relates that Mañjuśrî came from Wu-t'ai-Shan to adore a miraculous lotus[52] that appeared on the lake which then filled Nepal. With a blow of his sword he cleft the mountain barrier and thus drained the valley and introduced civilization. There may be hidden in this some tradition of the introduction of culture into Nepal but the Nepalese legends are late and in their collected form do not go back beyond the sixteenth century.

After Avalokita and Mañjuśrî the most important Bodhisattva is Maitreya,[53] also called Ajita or unconquered, who is the only one recognized by the Pali Canon.[54] This is because he does not stand on the same footing as the others. They are superhuman in their origin as well as in their career, whereas Maitreya is simply a being who like Gotama has lived innumerable lives and ultimately made himself worthy of Buddhahood which he awaits in heaven. There is no reason to doubt that Gotama regarded himself as one in [22] a series of Buddhas: the Pali scriptures relate that he mentioned his predecessors by name, and also spoke of unnumbered Buddhas to come.[55] Nevertheless Maitreya or Metteyya is rarely mentioned in the Pali Canon.[56] He is, however, frequently alluded to in the exegetical Pali literature, in the Anâgata-vaṃsa and in the earlier Sanskrit works such as the Lalita-vistara, the Divyâvadâna and Mahâvastu. In the Lotus he plays a prominent part, but still is subordinate to Mañjuśrî. Ultimately he was eclipsed by the two great Bodhisattvas but in the early centuries of our era he received much respect. His images are frequent in all parts of the Buddhist world: he was believed to watch over the propagation of the Faith,[57] and to have made special revelations to Asaṅga.[58] In paintings he is usually of a golden colour: his statues, which are often gigantic, show him standing or sitting in the European fashion and not cross-legged. He appears to be represented in the earliest Gandharan sculptures and there was a famous image of him in Udyâna of which Fa-Hsien (399-414 A.D.) speaks as if it were already ancient.[59] Hsüan Chuang describes it as well as a stupa erected[60] to commemorate Sâkyamuni's prediction that Maitreya would be his successor. On attaining Buddhahood he will become lord of a terrestrial paradise and hold three assemblies under a dragon flower tree,[61] at which all who have been good Buddhists in previous births will become Arhats. I-Ching speaks of meditating on the advent of Maitreya in language like that which Christian piety uses of the second coming of Christ and concludes a poem which is incorporated in his work with the aspiration "Deep as the depth of a lake be my pure and calm meditation. Let me look for the first meeting [23] under the Tree of the Dragon Flower when I hear the deep rippling voice of the Buddha Maitreya."[62] But messianic ideas were not much developed in either Buddhism or Hinduism and perhaps the figures of both Maitreya and Kalkî owe something to Persian legends about Saoshyant the Saviour.

The other Bodhisattvas, though lauded in special treatises, have left little impression on Indian Buddhism and have obtained in the Far East most of whatever importance they possess. The makers of images and miniatures assign to each his proper shape and colour, but when we read about them we feel that we are dealing not with the objects of real worship or even the products of a lively imagination, but with names and figures which have a value for picturesque but conventional art.

Among the best known is Samantabhadra, the all gracious,[63] who is still a popular deity in Tibet and the patron saint of the sacred mountain Omei in China, with which he is associated as Mañjuśrî with Wu-t́ai-shan. He is represented as green and riding on an elephant. In Indian Buddhism he has a moderately prominent position. He is mentioned in the Dharmasangraha and in one chapter of the Lotus he is charged with the special duty of protecting those who follow the law. But the Chinese pilgrims do not mention his worship.

Mahâsthâmaprâpta[64] is a somewhat similar figure. A chapter of the Lotus (XIX) is dedicated to him without however giving any clear idea of his personality and he is extolled in several descriptions of Sukhâvatî or Paradise, especially in the Amitâyurdhyâna-sûtra. Together with Amitâbha and Avalokita he forms a triad who rule this Happy Land and are often represented by three images in Chinese temples.

Vajrapâṇi is mentioned in many lists of Bodhisattvas (e.g. in the Dharmasangraha) but is of somewhat doubtful position as Hsüan Chuang calls him a deva.[65] Historically his recognition as a Bodhisattva is interesting for he is merely Indra transformed into a Buddhist. The mysterious personages called Vajradhara and Vajrasattva, who in later times are even [24] identified with the original Buddha spirit, are further developments of Vajrapâṇi. He owes his elevation to the fact that Vajra, originally meaning simply thunderbolt, came to be used as a mystical expression for the highest truth.

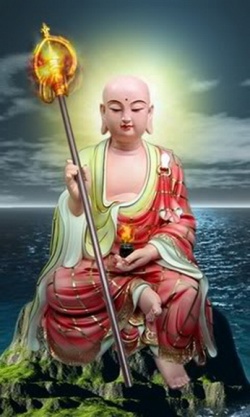

More important than these is Kshitigarbha, Ti-tsang or Jizō[66] who in China and Japan ranks second only to Kuan-yin. Visser has consecrated to him an interesting monograph[67] which shows what strange changes and chances may attend spirits and how ideal figures may alter as century after century they travel from land to land. We know little about the origin of Kshitigarbha. The name seems to mean Earth-womb and he has a shadowy counterpart in Akâśagarbha, a similar deity of the air, who it seems never had a hold on human hearts. The Earth is generally personified as a goddess[68] and Kshitigarbha has some slight feminine traits, though on the whole decidedly masculine. The stories of his previous births relate how he was twice a woman: in Japan he was identified with the mountain goddess of Kamado, and he helps women in labour, a boon generally accorded by goddesses. In the pantheon of India he played an inconspicuous part,[69] though reckoned one of the eight great Bodhisattvas, but met with more general esteem in Turkestan, where he began to collect the attributes afterwards defined in the Far East. It is there that his history and transformations become clear.

He is primarily a deity of the nether world, but like Amitâbha and Avalokita he made a vow to help all living creatures and specially to deliver them from hell. The Taoists pictured hell as divided into ten departments ruled over by as many kings, and Chinese fancy made Ti-tsang the superintendent of these functionaries. He thus becomes not so much a Saviour as the kindly superintendent of a prison who preaches to the inmates and willingly procures their release. Then we hear of six Ti-tsangs, corresponding to the six worlds of sentient beings, the gracious spirit being supposed to multiply his personality in [25] order to minister to the wants of all. He is often represented as a monk, staff in hand and with shaven head. The origin of this guise is not clear and it perhaps refers to his previous births. But in the eighth century a monk of Chiu Hua[70] was regarded as an incarnation of Ti-tsang and after death his body was gilded and enshrined as an object of worship. In later times the Bodhisattva was confused with the incarnation, in the same way as the portly figure of Pu-tai, commonly known as the laughing Buddha, has been substituted for Maitreya in Chinese iconography.

In Japan the cult of the six Jizōs became very popular. They were regarded as the deities of roads[71] and their effigies ultimately superseded the ancient phallic gods of the crossways. In this martial country the Bodhisattva assumed yet another character as Shōgun Jizō, a militant priest riding on horseback[72] and wearing a helmet who became the patron saint of warriors and was even identified with the Japanese war god, Hachiman. Until the seventeenth century Jizō was worshipped principally by soldiers and priests, but subsequently his cult spread among all classes and in all districts. His benevolent activities as a guide and saviour were more and more emphasized: he heals sickness, he leng thens life, he leads to heaven, he saves from hell: he even suffers as a substitute in hell and is the special protector of the souls of children amid the perils of the underworld. Though this modern figure of Jizō is wrought with ancient materials, it is in the main a work of Japanese sentiment.

FOOTNOTES:

[5] In dealing with the Mahayanists, I use the expression Śâkyamuni in preference to Gotama. It is their own title for the teacher and it seems incongruous to use the purely human name of Gotama in describing doctrines which represent him as superhuman.

[6] But Kings Hsin-byu-shin of Burma and Śrî Sûryavaṃsa Râma of Siam have left inscriptions recording their desire to become Buddhas. See my chapters on Burma and Siam below. Mahayanist ideas may easily have entered these countries from China, but even in Ceylon the idea of becoming a Buddha or Bodhisattva is not unknown. See Manual of a Mystic (P.T.S. 1916), pp. xviii and 140.

[7] E.g. in Itivuttakam 75, there is a description of the man who is like a drought and gives nothing, the man who is like rain in a certain district and the man who is Sabbabhûtânukampako, compassionate to all creatures, and like rain falling everywhere. Similarly Ib. 84, and elsewhere, we have descriptions of persons (ordinary disciples as well as Buddhas) who are born for the welfare of gods and men bahujanahitâya, bahujanasukhâya, lokânukampâya, atthâya, hitâya, sukhâya devamanussânam.

[8] Ed. Senart, vol. I. p. 142.

[9] The Bodhicaryâvatâra was edited by Minayeff, 1889 and also in the Journal of the Buddhist Text Society and the Bibliotheca Indica. De la Vallée Poussin published parts of the text and commentary in his Bouddhisme and also a translation in 1907.

[10] The career of the Bodhisattva is also discussed in detail in the Avatamsaka sûtra and in works attributed to Nâgârjuna and Sthiramati, the Lakshaṇa-vimukta-hṛidaya-śâstra and the Mahâyâna-dharma-dhâtvaviśeshata-śâstra. I only know of these works as quoted by Teitaro Suzuki.

[11] See Childers, Pali Dict. s.v. Patti, Pattianuppadânam and Puñño.

[12] It occurs in the Pali Canon, e.g. Itivuttakam 100. Tassa me tumhe puttâ orasâ, mukhato jâtâ, dhammajâ.

[13] See Sylvain Lévi, Mahâyâna-sûtrâlankâra: introduction and passim. For much additional information about the Bhûmis see De la Vallée Poussin's article "Bodhisattva" in E.R.E.

[14] Eminent doctors such as Nâgârjuna and Asanga are often described as Bodhisattvas just as eminent Hindu teachers, e.g. Caitanya, are described as Avatâras.

[15] The idea that Arhats may postpone their entry into Nirvana for the good of the world is not unknown to the Pali Canon. According to the Maha Parin-Sutta the Buddha himself might have done so. Legends which cannot be called definitely Mahayanist relate how Piṇḍola and others are to tarry until Maitreya come and how Kâśyapa in a less active role awaits him in a cave or tomb, ready to revive at his advent. See J.A. 1916, II. pp. 196, 270.

[16] E.g. Lotus, chap. I.

[17] De la Vallée Poussin's article "Avalokita" in E.R.E. may be consulted.

[18] Lotus, S.B.E. XXI. p. 407.

[19] sPyan-ras-gzigs rendered in Mongol by Nidübär-üdzäkci. The other common Mongol name Ariobalo appears to be a corruption of Âryâvalokita.

[20] Meaning apparently the seeing and self-existent one. Cf. Ta-tzǔ-tsai as a name of Śiva.

[21] A maidservant in the drama Mâlatîmâdhava is called Avalokita. It is not clear whether it is a feminine form of the divine name or an adjective meaning looked-at, or admirable.

[22] S.B.E. XXI. pp. 4 and 406 ff. It was translated in Chinese between A.D. 265 and 316 and chap. XXIV was separately translated between A.D. 384 and 417. See Nanjio, Catalogue Nos. 136, 137, 138.

[23] Hsüan Chuang (Watters, II. 215, 224) relates how an Indian sage recited the Sui-hsin dhârani before Kuan-tzǔ-tsai's image for three years.

[24] As will be noticed from time to time in these pages, the sudden appearance of new deities in Indian literature often seems strange. The fact is that until deities are generally recognized, standard works pay no attention to them.

[25] Watters, vol. II. pp. 228 ff. It is said that Potalaka is also mentioned in the Hwa-yen-ching or Avatamsaka sûtra. Tibetan tradition connects it with the Śâkya family. See Csoma de Körös, Tibetan studies reprinted 1912, pp. 32-34.

[26] Just as the Lankâvatâra sûtra purports to have been delivered at Lankapura-samudra-malaya-śikhara rendered in the Chinese translation as "in the city of Lanka on the summit of the Malaya mountain on the border of the sea."

[27] See Foucher, Iconographie bouddhique, 1900, pp. 100, 102.

[28] Varamudra.

[29] These as well as the red colour are attributes of the Hindu deity Brahmâ.

[30] A temple on the north side of the lake in the Imperial City at Peking contains a gigantic image of him which has literally a thousand heads and a thousand hands. This monstrous figure is a warning against an attempt to represent metaphors literally.

[31] Waddell on the Cult of Avalokita, J.R.A.S. 1894, pp. 51 ff. thinks they are not earlier than the fifth century.

[32] See especially Foucher, Iconographie Bouddhique, Paris, 1900.

[33] See especially de Blonay, Études pour servir à l'histoire de la déesse bouddhique Târâ, Paris, 1895. Târâ continued to be worshipped as a Hindu goddess after Buddhism had disappeared and several works were written in her honour. See Raj. Mitra, Search for Sk. MSS. IV. 168, 171, X. 67.

[34] About the time of Hsüan Chuang's travels Sarvajñâmitra wrote a hymn to Târâ which has been preserved and published by de Blonay, 1894.

[35] Chinese Buddhists say Târâ and Kuan-Yin are the same but the difference between them is this. Târâ is an Indian and Lamaist goddess associated with Avalokita and in origin analogous to the Saktis of Tantrism. Kuan-yin is a female form of Avalokita who can assume all shapes. The original Kuan-yin was a male deity: male Kuan-yins are not unknown in China and are said to be the rule in Korea. But Târâ and Kuan-yin may justly be described as the same in so far as they are attempts to embody the idea of divine pity in a Madonna.

[36] But many scholars think that the formula Om manipadme hum, which is supposed to be addressed to Avalokita, is really an invocation to a form of Śakti called Maṇipadmâ. A Nepalese inscription says that "The Śâktas call him Śakti" (E.R.E. vol. II. p. 260 and J.A. IX. 192), but this may be merely a way of saying that he is identical with the great gods of all sects.

[37] Harlez, Livre des esprits et des immortels, p. 195, and Doré, Recherches sur les superstitions en Chine, pp. 94-138.

[38] See Fenollosa, Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art I. pp. 105 and 124; Johnston, Buddhist China, 275 ff. Several Chinese deities appear to be of uncertain or varying sex. Thus Chun-ti is sometimes described as a deified Chinese General and sometimes identified with the Indian goddess Marîcî. Yü-ti, generally masculine, is sometimes feminine. See Doré, l.c. 212. Still more strangely the Patriarch Aśvaghosha (Ma Ming) is represented by a female figure. On the other hand the monk Ta Shêng (c. 705 A.D.) is said to have been an incarnation of the female Kuan Yin. Mañjuśrî is said to be worshipped in Nepal sometimes as a male, sometimes as a female. See Bendall and Haraprasad, Nepalese MSS. p. lxvii.

[39] de Blonay, l.c. pp. 48-57.

[40] Chinese, Man-chu-shih-li, or Wên-shu; Japanese, Monju; Tibetan, hJam-pahi-dbyans (pronounced Jam-yang). Mañju is good Sanskrit, but it must be confessed that the name has a Central-Asian ring.

[41] Translated into Chinese 270 A.D.

[42] Chaps. XI. and XIII.

[43] A special work Mañjuśrîvikrîḍita (Nanjio, 184, 185) translated into Chinese 313 A.D. is quoted as describing Mañjuśrî's transformations and exploits.

[44] Hsüan Chuang also relates how he assisted a philosopher called Ch'en-na (=Diṅnâga) and bade him study Mahayanist books.

[45] It is reproduced in Grünwedel's Buddhist Art in India. Translated by Gibson, 1901, p. 200.

[46] Dharmacakramudra.

[47] For the Nepalese legends see S. Levi, Le Nepal, 1905-9.

[48] For an account of this sacred mountain see Edkins, Religion in China, chaps. XVII to XIX.

[49] See I-tsing, trans. Takakusu, 1896, p. 136. For some further remarks on the possible foreign origin of Mañjuśrî see below, chapter on Central Asia. The verses attributed to King Harsha (Nanjio, 1071) praise the reliquaries of China but without details.

[50] Some of the Tantras, e.g. the Mahâcînakramâcâra, though they do not connect Mañjuśrî with China, represent some of their most surprising novelties as having been brought thence by ancient sages like Vasishṭha.

[51] J.R.A.S. new series, XII. 522 and J.A.S.B. 1882, p. 41. The name Manchu perhaps contributed to this belief.

[52] It is described as a Svayambhû or spontaneous manifestation of the Âdi-Buddha.

[53] Sanskrit, Maitreya; Pali, Metteyya; Chinese, Mi-li; Japanese, Miroku; Mongol, Maidari; Tibetan, Byams-pa (pronounced Jampa). For the history of the Maitreya idea see especially Péri, B.E.F.E.O. 1911, pp. 439-457.

[54] But a Siamese inscription of about 1361, possibly influenced by Chinese Mahayanism, speaks of the ten Bodhisattvas headed by Metteyya. See B.E.F.E.O. 1917, No. 2, pp. 30, 31.

[55] E.g. in the Mahâparinibbâna Sûtra.

[56] Dig. Nik. XXVI. 25 and Buddhavamsa, XXVII. 19, and even this last verse is said to be an addition.

[57] See e.g. Watters, Yüan Chwang, I. 239.

[58] See Watters and Péri in B.E.F.E.O. 1911, 439. A temple of Maitreya has been found at Turfan in Central Asia with a Chinese inscription which speaks of him as an active and benevolent deity manifesting himself in many forms.

[59] He has not fared well in Chinese iconography which represents him as an enormously fat smiling monk. In the Liang dynasty there was a monk called Pu-tai (Jap. Hotei) who was regarded as an incarnation of Maitreya and became a popular subject for caricature. It would appear that the Bodhisattva himself has become superseded by this cheerful but undignified incarnation.

[60] The stupa was apparently at Benares but Hsüan Chuang's narrative is not clear and other versions make Râjagṛiha or Srâvasti the scene of the prediction.

[61] Campa. This is his bodhi tree under which he will obtain enlightenment as Sâkyamuni under the Ficus religiosa. Each Buddha has his own special kind of bodhi tree.

[62] Record of the Buddhist religion, Trans. Takakusu, p. 213. See too Watters, Yüan Chwang, II. 57, 144, 210, 215.

[63] Chinese P'u-hsien. See Johnston, From Peking to Mandalay, for an interesting account of Mt. Omei.

[64] Or Mahâsthâna. Chinese, Tai-shih-chih. He appears to be the Arhat Maudgalyâyana deified. In China and Japan there is a marked tendency to regard all Bodhisattvas as ancient worthies who by their vows and virtues have risen to their present high position. But these euhemeristic explanations are common in the Far East and the real origin of the Bodhisattvas may be quite different.

[65] E.g. Watters, I. p. 229, II. 215.

[66] Kshitigarbha is translated into Chinese as Ti-tsang and Jizō is the Japanese pronunciation of the same two characters.

[67] In Ostasiat. Ztsft. 1913-15. See too Johnston, Buddhist China, chap. VIII.

[68] The Earth goddess is known to the earliest Buddhist legends. The Buddha called her to witness when sitting under the Bo tree.

[69] Three Sûtras, analysed by Visser, treat of Kshitigarbha. They are Nanjio, Nos. 64, 65, 67.

[70] A celebrated monastery in the portion of An-hui which lies to the south of the Yang-tse. See Johnston, Buddhist China, chaps, VIII, IX and X.

[71] There is some reason to think that even in Turkestan Kshitigarbha was a god of roads.

[72] In Annam too Jizō is represented on horseback.

CHAPTER XVIII

THE BUDDHAS OF MAHAYANISM

This mythology did not grow up around the Buddha without affecting the central figure. To understand the extraordinary changes of meaning both mythological and metaphysical which the word Buddha undergoes in Mahayanist theology we must keep in mind not the personality of Gotama but the idea that he is one of several successive Buddhas who for convenience may be counted as four, seven or twenty-four but who really form an infinite series extending without limit backwards into the past and forwards into the future.[73] This belief in a series of Buddhas produced a plentiful crop of imaginary personalities and also of speculations as to their connection with one another, with the phenomena of the world and with the human soul.

In the Pali Canon the Buddhas antecedent to Gotama are introduced much like ancient kings as part of the legendary history of this world. But in the Lalita-vistara (Chap. XX) and the Lotus (Chap. VII) we hear of Buddhas, usually described as Tathâgatas, who apparently do not belong to this world at all, but rule various points of the compass, or regions described as Buddha-fields (Buddha-kshetra). Their names are not the same in the different accounts and we remain dazzled by an endless panorama of an infinity of universes with an infinity of shining Buddhas, illuminating infinite space.

Somewhat later five of these unearthly Buddhas were formed into a pentad and described as Jinas[74] or Dhyâni Buddhas (Buddhas of contemplation), namely, Vairocana, Akshobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitâbha and Amoghasiddhi. In the fully developed form of this doctrine these five personages [27]are produced by contemplation from the Âdi-Buddha or original Buddha spirit and themselves produce various reflexes, including Bodhisattvas, human Buddhas and goddesses like Târâ. The date when these beliefs first became part of the accepted Mahayana creed cannot be fixed but probably the symmetrical arrangement of five Buddhas is not anterior to the tantric period[75] of Buddhism.

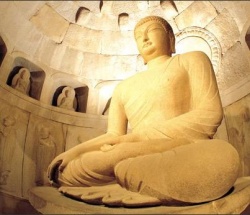

The most important of the five are Vairocana and Amitâbha. Akshobhya is mentioned in both the Lotus and Smaller Sukhâvatî-vyûha as the chief Buddha of the eastern quarter, and a work purporting to be a description of his paradise still extant in Chinese[76] is said to have been translated in the time of the Eastern Han dynasty. But even in the Far East he did not find many worshippers. More enduring has been the glory of Vairocana who is the chief deity of the Shingon sect in Japan and is represented by the gigantic image in the temple at Nara. In Java he seems to have been regarded as the principal and supreme Buddha. The name occurs in the Mahâvastu as the designation of an otherwise unknown Buddha of luminous attributes and in the Lotus we hear of a distant Buddha-world called Vairocana-rasmi-pratimandita, embellished by the rays of the sun.[77] Vairocana is clearly a derivative of Virocana, a recognized title of the sun in Sanskrit, and is rendered in Chinese by Ta-jih meaning great Sun. How this solar deity first came to be regarded as a Buddha is not known but the connection between a Buddha and light has always been recognized. Even the Pali texts represent Gotama as being luminous on some occasions and in the Mahayanist scriptures Buddhas are radiant and light-giving beings, surrounded by halos of prodigious extent and emitting flashes which illuminate the depths of space. The visions of innumerable paradises in all quarters containing jewelled stupas and lighted by refulgent Buddhas which are frequent in these works seem founded on astronomy vaporized under the influence of the idea that there are millions of universes all equally transitory and unsubstantial. There is no reason, so [28]far as I see, to regard Gotama as a mythical solar hero, but the celestial Buddhas[78] clearly have many solar attributes. This is natural. Solar deities are so abundant in Vedic mythology that it is hardly possible to be a benevolent god without having something of the character of the sun. The stream of foreign religions which flowed into India from Bactria and Persia about the time of the Christian era brought new aspects of sun worship such as Mithra, Helios and Apollo and strengthened the tendency to connect divinity and light. And this connection was peculiarly appropriate and obvious in the case of a Buddha, for Buddhas are clearly revealers and light-givers, conquerors of darkness and dispellers of ignorance.

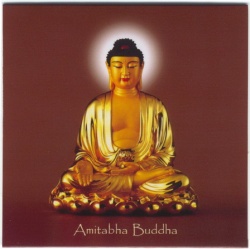

Amitâbha (or the Buddha of measureless light), rising suddenly from an obscure origin, has like Avalokita and Vishnu become one of the great gods of Asia. He is also known as Amitâyus or measureless life, and is therefore a god of light and immortality. According to both the Lotus and the Smaller Sukhâvatî-vyûha he is the lord of the western quarter but he is unknown to the Lalita-vistara. It gives the ruler of the west a lengthy title,[79] which suggests a land of gardens. Now Paradise, which has biblical authority as a name for the place of departed spirits, appears to mean in Persian a park or enclosed garden and the Avesta speaks of four heavens, the good thought Paradise, the good word Paradise, the good deed Paradise and the Endless Lights.[80] This last expression bears a remarkable resemblance to the name of Amitâbha and we can understand that he should rule the west, because it is the home to which the sun and departed spirits go. Amitâbha's Paradise is called Sukhâvatî or Happy Land. In the Puranas the city of Varuṇa (who is suspected of having a non-Indian origin) is said to be situated in the west and is called Sukha (Linga P. and Vayu P.) or Mukhya (so Vishnu P. and others). The name Amitâbha also occurs in the Vishnu Purana as the name of a class of gods and it is curious that they are in one place[81] associated with [29]other deities called the Mukhyas. The worship of Amitâbha, so far as its history can be traced, goes back to Saraha, the teacher of Nâgârjuna. He is said to have been a Sudra and his name seems un-Indian. This supports the theory that this worship was foreign and imported into India.[82]

This worship and the doctrine on which it is based are an almost complete contradiction of Gotama's teaching, for they amount to this, that religion consists in faith in Amitâbha and prayer to him, in return for which he will receive his followers after death in his paradise. Yet this is not a late travesty of Buddhism but a relatively early development which must have begun about the Christian era. The principal works in which it is preached are the Greater Sukhâvatî-vyûha or Description of the Happy Land, translated into Chinese between 147 and 186 A.D., the lesser work of the same name translated in 402 A.D. and the Sûtra of meditation on Amitâyus[83] translated in 424. The first of these works purports to be a discourse of Śâkyamuni himself, delivered on the Vulture's Peak in answer to the questions of Ânanda. He relates how innumerable ages ago there was a monk called Dharmâkara who, with the help of the Buddha of that period, made a vow or vows[84] to become a Buddha but on conditions. That is to say he rejected the Buddhahood to which he might become entitled unless his merits obtained certain advantages for others, and having obtained Buddhahood on these conditions he can now cause them to be fulfilled. In other words he can apportion his vast store of accumulated merit to such persons and in such manner as he chooses. The gist of the conditions is that he should when he obtained Buddhahood be lord of a paradise whose inhabitants live in unbroken happiness until they obtain Nirvana. All who have thought of this paradise ten times are to be admitted therein, unless they have committed grievous sin, and Amitâbha will appear to them at the moment of death so that their thoughts may not be troubled. The Buddha shows Ânanda a [30] miraculous vision of this paradise and its joys are described in language recalling the account of the New Jerusalem in the book of Revelation and, though coarser pleasures are excluded, all the delights of the eye and ear, such as jewels, gardens, flowers, rivers and the songs of birds await the faithful.

The smaller Sukhâvatî-vyûha, represented as preached by Śâkyamuni at Śrâvasti, is occupied almost entirely with a description of the paradise. It marks a new departure in definitely preaching salvation by faith only, not by works, whereas the previous treatise, though dwelling on the efficacy of faith, also makes merit a requisite for life in heaven. But the shorter discourse says dogmatically "Beings are not born in that Buddha country as a reward and result of good works performed in this present life. No, all men or women who hear and bear in mind for one, two, three, four, five, six or seven nights the name of Amitâyus, when they come to die, Amitâyus will stand before them in the hour of death, they will depart this life with quiet minds and after death they will be born in Paradise."

The Amitâyur-dhyâna-sûtra also purports to be the teaching of Śâkyamuni and has an historical introduction connecting it with Queen Vaidehî and King Bimbisâra. In theology it is more advanced than the other treatises: it is familiar with the doctrine of Dharma-kâya (which will be discussed below) and it represents the rulers of paradise as a triad, Amitâyus being assisted by Avalokita and Mahasthâmaprâpta.[85] Admission to the paradise can be obtained in various ways, but the method recommended is the practice of a series of meditations which are described in detail. The system is comprehensive, for salvation can be obtained by mere virtue with little or no prayer but also by a single invocation of Amitâyus, which suffices to free from deadly sins.

Strange as such doctrines appear when set beside the Pali texts, it is clear that in their origin and even in the form which they assume in the larger Sukhâvatî-vyûha they are simply an exaggeration of ordinary Mahayanist teaching.[86] Amitâbha is [31] merely a monk who devotes himself to the religious life, namely seeking bodhi for the good of others. He differs from every day devotees only in the degree of sanctity and success obtained by his exertions. The operations which he performs are nothing but examples on a stupendous scale of pariṇâmanâ or the assignment of one's own merits to others. His paradise, though in popular esteem equivalent to the Persian or Christian heaven, is not really so: strictly speaking it is not an ultimate ideal but a blessed region in which Nirvana may be obtained without toil or care.

Though this teaching had brilliant success in China and Japan, where it still flourishes, the worship of Amitâbha was never predominant in India. In Nepal and Tibet he is one among many deities: the Chinese pilgrims hardly mention him: his figure is not particularly frequent in Indian iconography[87] and, except in the works composed specially in his honour, he appears as an incidental rather than as a necessary figure. The whole doctrine is hardly strenuous enough for Indians. To pray to the Buddha at the end of a sinful life, enter his paradise and obtain ultimate Nirvana in comfort is not only open to the same charge of egoism as the Hinayana scheme of salvation but is much easier and may lead to the abandonment of religious effort. And the Hindu, who above all things likes to busy himself with his own salvation, does not take kindly to these expedients. Numerous deities promise a long spell of heaven as a reward for the mere utterance of their names,[88] yet the believer continues to labour earnestly in ceremonies or meditation. It would be interesting to know whether this doctrine of salvation by the utterance of a single name or prayer originated among Buddhists or Brahmans. In any case it is closely related to old ideas about the magic power of Vedic verses.

The five Jinas and other supernatural personages are often regarded as manifestations of a single Buddha-force and at last this force is personified as Âdi-Buddha.[89] This admittedly [32] theistic form of Buddhism is late and is recorded from Nepal, Tibet (in the Kâlacakra system) and Java, a distribution which implies that it was exported from Bengal.[90] But another form in which the Buddha-force is impersonal and analogous to the Parabrahma of the Vedânta is much older. Yet when this philosophic idea is expressed in popular language it comes very near to Theism. As Kern has pointed out, Buddha is not called Deva or Îśvara in the Lotus simply because he is above such beings. He declares that he has existed and will exist for incalculable ages and has preached and will preach in innumerable millions of worlds. His birth here and his nirvana are illusory, kindly devices which may help weak disciples but do not mark the real beginning and end of his activity. This implies a view of Buddha's personality which is more precisely defined in the doctrine known as Ṭrikâya or the three bodies[91] and expounded in the Mahâyâna-sûtrâlankâra, the Awakening of Faith, the Suvarṇa-prabhâsa sûtra[92] and many other works. It may be stated dogmatically as follows, but it assumes somewhat divergent forms according as it is treated theologically or metaphysically.

A Buddha has three bodies or forms of existence. The first is the Dharma-kâya, which is the essence of all Buddhas. It is true knowledge or Bodhi. It may also be described as Nirvana and also as the one permanent reality underlying all phenomena and all individuals. The second is the Sambhoga-kâya, or body of enjoyment, that is to say the radiant and superhuman form in which Buddhas appear in their paradises or when otherwise manifesting themselves in celestial splendour. The third is the Nirmâna-kâya, or the body [33] of transformation, that is to say the human form worn by Śâkyamuni or any other Buddha and regarded as a transformation of his true nature and almost a distortion, because it is so partial and inadequate an expression of it. Later theology regards Amitâbha, Amitâyus and Śâkyamuni as a series corresponding to the three bodies. Amitâbha does not really express the whole Dharma-kâya, which is incapable of personification, but when he is accurately distinguished from Amitâyus (and frequently they are regarded as synonyms) he is made the more remote and ethereal of the two. Amitâyus with his rich ornaments and his flask containing the water of eternal life is the ideal of a splendidly beneficent saviour and represents the Sambhoga-kâya.[93] Śâkyamuni is the same beneficent being shrunk into human form. But this is only one aspect, and not the most important, of the doctrine of the three bodies. We can easily understand the Sambhoga-kâya and Nirmâna-kâya: they correspond to a deity such as Vishnu and his incarnation Krishna, and they are puzzling in Buddhism simply because we think naturally of the older view (not entirely discarded by the Mahayana) which makes the human Buddha the crown and apex of a series of lives that find in him their fulfilment. But it is less easy to understand the Dharma-kâya.

The word should perhaps be translated as body of the law and the thought originally underlying it may have been that the essential nature of a Buddha, that which makes him a Buddha, is the law which he preaches. As we might say, the teacher lives in his teaching: while it survives, he is active and not dead.

The change from metaphor to theology is illustrated by Hsüan Chuang when he states[94] (no doubt quoting from his edition of the Pitakas) that Gotama when dying said to those around him "Say not that the Tathâgata is undergoing final [34] extinction: his spiritual presence abides for ever unchangeable." This apparently corresponds to the passage in the Pali Canon,[95] which runs "It may be that in some of you the thought may arise, the word of the Master is ended: we have no more a teacher. But it is not thus that you should regard it. The truths and the rules which I have set forth, let them, after I am gone, be the Teacher to you." But in Buddhist writings, including the oldest Pali texts, Dharma or Dhamma has another important meaning. It signifies phenomenon or mental state (the two being identical for an idealistic philosophy) and comprises both the external and the internal world. Now the Dharma-kâya is emphatically not a phenomenon but it may be regarded as the substratum or totality of phenomena or as that which gives phenomena whatever reality they possess and the double use of the word dharma rendered such divagations of meaning easier.[96] Hindus have a tendency to identify being and knowledge. According to the Vedânta philosophy he who knows Brahman, knows that he himself is Brahman and therefore he actually is Brahman. In the same way the true body of the Buddha is prajñâ or knowledge.[97] By this is meant a knowledge which transcends the distinction between subject and object and which sees that neither animate beings nor inanimate things have individuality or separate existence. Thus the Dharma-kâya being an intelligence which sees the illusory quality of the world and also how the illusion originates[98] may be regarded as the origin and ground of all phenomena. As such it is also called Tathâgatagarbha and Dharma-dhâtu, the matrix or store-house of all phenomena. On the other hand, inasmuch as it is beyond them and implies their unreality, it may also be regarded as the annihilation of all phenomena, in other words as Nirvana. In fact the Dharma-kâya (or Bhûta-tathatâ) is sometimes[99] defined in words similar to those which the Pali Canon makes the Buddha use when asked if the Perfect Saint exists after death—"it is neither that which is existence nor that which is non-existence, nor that which is at once existence and non-existence nor that which is neither existence nor [35] non-existence." In more theological language it may be said that according to the general opinion of the Mahayanists a Buddha attains to Nirvana by the very act of becoming a Buddha and is therefore beyond everything which we call existence. Yet the compassion which he feels for mankind and the good Karma which he has accumulated cause a human image of him (Nirmâna-kâya) to appear among men for their instruction and a superhuman image, perceptible yet not material, to appear in Paradise.

FOOTNOTES:

[73] In Mahâparinib. Sut. I. 16 the Buddha is made to speak of all the other Buddhas who have been in the long ages of the past and will be in the long ages of the future.

[74] Though Dhyâni Buddha is the title most frequently used in European works it would appear that Jina is more usual in Sanskrit works, and in fact Dhyâni Buddha is hardly known outside Nepalese literature. Ratnasambhava and Amoghasiddhi are rarely mentioned apart from the others. According to Getty (Gods of Northern Buddhism, pp. 26, 27) a group of six, including the Âdi-Buddha himself under the name of Vajrasattva, is sometimes worshipped.

[75] About the same period Śiva and Vishnu were worshipped in five forms. See below, Book V. chap. III. sec. 3 ad fin.

[76] Nanjio, Cat. No. 28.

[77] Virocana also occurs in the Chândogya Up. VIII. 7 and 8 as the name of an Asura who misunderstood the teaching of Prajâpati. Verocana is the name of an Asura in Sam. Nik. I. xi. 1. 8.

[78] The names of many of these Buddhas, perhaps the majority, contain some word expressive of light such as Âditya, prabhâ or tejas.

[79] Chap. XX. Pushpavalivanârajikusumitâbhijña.

[80] E.g. Yashts. XXII. and XXIV. S.B.E. vol. XXIII. pp. 317 and 344. The title Pure Land (Chinese Ch'ing-t'u, Japanese Jo-do) has also a Persian ring about it. See further in the chapter on Central Asia.

[81] Vishnu P., Book III. chap. II.

[82] See below: Section on Central Asia, and Grünwedel, Mythologie, 31, 36 and notes: Taranatha (Shiefner), p. 93 and notes.

[83] Amitâyur-dhyâna-sûtra. All three works are translated in S.B.E. vol. XLIX.

[84] Praṇidhâna. Not only Amitâbha but all Bodhisattvas (especially Avalokita and Kshitigarbha) are supposed to have made such vows. This idea is very common in China and Japan but goes back to Indian sources. See e.g. Lotus, XXIV. verse 3.