Difference between revisions of "Aloha Buddha—the secularization of ethnic Japanese-American Buddhism by Jørn Borup"

m (1 revision: Robo text replace 30 sept) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

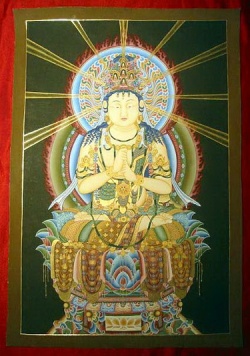

[[File:010.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:010.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

Journal of Global [[Buddhism]] 14 (2013): 23-43 | Journal of Global [[Buddhism]] 14 (2013): 23-43 | ||

| − | Aloha | + | Aloha [[Buddha]]—the secularization of {{Wiki|ethnic}} Japanese-American [[Buddhism]] by Jørn [[Borup]] |

| + | |||

| + | Aarhus {{Wiki|University}} | ||

| − | + | Department of {{Wiki|Culture}} and {{Wiki|Society}} | |

| − | Department of Culture and {{Wiki|Society}} | ||

R e s e a r c h A r t i c l e | R e s e a r c h A r t i c l e | ||

| − | Jørn Borup | + | Jørn [[Borup]] |

| Line 17: | Line 28: | ||

Abstract | Abstract | ||

| − | The relations between [[religion]], migration, transnationalism, pluralism, and ethnicity have gained increasing focus in [[religious]], cultural, sociological, and anthropological studies. With its manifold transfigurations across [[time]] and location, [[Buddhism]] is an obvious case for investigating such issues. Hawaii, with its long migration {{Wiki|history}} and [[religious]] pluralism, is an obvious living laboratory for studying such configurations. This article investigates {{Wiki|Japanese}} American [[Buddhism]] in Hawaii, focusing on the relationship between [[religion]] and ethnicity. By analyzing contemporary [[religious]] [[life]] and the historical context of two | + | The relations between [[religion]], migration, transnationalism, [[pluralism]], and ethnicity have gained increasing focus in [[religious]], {{Wiki|cultural}}, {{Wiki|sociological}}, and anthropological studies. With its manifold transfigurations across [[time]] and location, [[Buddhism]] is an obvious case for investigating such issues. [[Hawaii]], with its long |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | migration {{Wiki|history}} and [[religious]] [[pluralism]], is an obvious living laboratory for studying such configurations. This article investigates {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[American]] [[Buddhism]] in [[Hawaii]], focusing on the relationship between [[religion]] and ethnicity. By analyzing contemporary [[religious]] [[life]] and the historical | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | context of two [[Japanese American Zen temples]] in [[Maui]], it is argued that the {{Wiki|ethnic}} and {{Wiki|cultural}} divide related to [[spirituality]] follow a general tendency by which the secularization of {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]]’ communal [[Sangha]] [[Buddhism]] is counterbalanced by a different group’s spiritualization of [[Buddhism]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Japanese]] [[Buddhism]] is {{Wiki|present}} in several [[Western]] regions (Pereira and Matsuoka, | ||

| + | 2007), characterized by a [[division]] between the two “kinds” of [[Buddhism]]. In [[North America]] “[[religion]] and ethnicity are closely related [[phenomena]]” (Tanaka, 1999: 5). Not only the {{Wiki|Japanese}} new [[religions]], | ||

| + | |||

| + | but also [[Zen]] [[Buddhism]], which in its “[[Western]]” [[form]] can also be regarded as a new [[religious]] {{Wiki|movement}} (Sharf, 1995a and b), have appealed to Euro-Americans, while other [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Buddhist]] [[traditions]] have been used and [[transformed]] by different immigrant waves settling in countries such as the {{Wiki|USA}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | (Kashima, 1977; [[Asai]] & [[Williams]], 1999; [[Williams]] and {{Wiki|Moriya}}, 2010), {{Wiki|Brazil}} (Rocha, 2006; Usarski, 2008), and {{Wiki|Canada}} (Harding, Hori and Soucy, 2010; Mullins, 1988). [[Hawaii]] is in many ways a particularly [[interesting]] place for observing immigrant [[Buddhism]] (Ama, 2011; {{Wiki|Hunter}}, 1971; Kashima, 2008; [[Tanabe]], 2005; | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Tanabe]] and [[Tanabe]], forthcoming) as it constitutes both the “[[American]] [[West]]” and “Pacific [[East]]” ([[Williams]] and {{Wiki|Moriya}} 2010, x). The first {{Wiki|Japanese}} came to [[Hawaii]] five generations ago, establishing a migrant {{Wiki|community}} whose descendants often identify themselves as {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]]. Such hyphenization is common in [[Hawaii]], where hybrid identification challenges [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] and bounded categories such as ethnicity and race. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Furthermore, according to [[Lamb]], [[Hawaii]] is “among the most religiously diverse areas in the [[world]]” (1998: 210) with one [[religious]] center for every 1,000 [[people]] (ibid.), thus, even though the reference is fifteen years old, [[Hawaii]] remains quintessentially an example of {{Wiki|cultural}} and [[religious]] [[pluralism]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[File:100000174.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:100000174.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | 1 This project is part of the research project [[Buddhism]] and Modernity, funded by the Danish [[Council]] for Independent Research. Part of this article has appeared in Danish in the journal Religionsvidenskabeligt Tidsskrift (2012). The title of the article is not otherwise related to the documentary film Aloha [[Buddha]]. The Story of [[Japanese Buddhism]] in Hawaii (directed by Bill Ferehawk and Dylan Robertson and produced by Lorraine Minatoishi-Palumbo). | + | 1 This project is part of the research project [[Buddhism]] and Modernity, funded by the {{Wiki|Danish}} [[Council]] for Independent Research. Part of this article has appeared in {{Wiki|Danish}} in the journal Religionsvidenskabeligt Tidsskrift (2012). The title of the article is not otherwise related to the documentary film Aloha [[Buddha]]. The Story of [[Japanese Buddhism]] in [[Hawaii]] (directed by Bill Ferehawk and Dylan Robertson and produced by Lorraine Minatoishi-Palumbo). |

| − | The [[aim]] of this article is, via historical outline and investigation of contemporary [[religious]] communities, to analyze how and to what extent ethnicity plays and has played a role in [[Japanese Buddhism]] in Hawaii. The [[empirical]] {{Wiki|data}} used in this article is based on fieldwork in the village of Paia on the north coast of the island of Maui.2 The place was chosen primarily because former research on contemporary [[Rinzai]] [[Zen]] [[Buddhism in Japan]] (Borup, 2008) might act as a comparative frame for investigating the only [[Rinzai]] [[temple]] related to My6shinji abroad ([[Rinzai]] [[Zen]] Mission). Furthermore, the village contains a S6t6 [[Zen]] [[temple]] (Mantokuji), a small lay [[Zen]] group (Maui Zendo), as well as a thriving [[spiritual]] market, making comparison between different kinds of (uses of) [[Buddhism]] possible. Analyses of the cases are further discussed in relation to general tendencies in immigrant [[Buddhism]] in a contemporary pluralist context in which a growing [[spiritual]] market has also adopted [[Buddhist]] [[elements]]. It is argued that ethnicity has played important and different roles in the {{Wiki|history}} of Japanese-American [[Buddhism]] and that {{Wiki|ethnic}} divisions in different kinds of contemporary religiosity are related to both secularization and spiritualization of [[Buddhism]]. | + | The [[aim]] of this article is, via historical outline and [[investigation]] of contemporary [[religious]] communities, to analyze how and to what extent ethnicity plays and has played a role in [[Japanese Buddhism]] in [[Hawaii]]. The [[empirical]] {{Wiki|data}} used in this article is based on fieldwork in the village of Paia on the [[north]] coast of |

| + | |||

| + | the [[island]] of Maui.2 The place was chosen primarily because former research on contemporary [[Rinzai]] [[Zen]] [[Buddhism in Japan]] ([[Borup]], 2008) might act as a comparative frame for investigating the only [[Rinzai]] [[temple]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | related to My6shinji abroad ([[Rinzai]] [[Zen]] [[Mission]]). Furthermore, the village contains a S6t6 [[Zen]] [[temple]] (Mantokuji), a small lay [[Zen]] group ([[Maui Zendo]]), as well as a thriving [[spiritual]] market, making | ||

| + | |||

| + | comparison between different kinds of (uses of) [[Buddhism]] possible. Analyses of the cases are further discussed in [[relation]] to general {{Wiki|tendencies}} in immigrant [[Buddhism]] in a contemporary {{Wiki|pluralist}} context in which a growing | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[spiritual]] market has also adopted [[Buddhist]] [[elements]]. It is argued that ethnicity has played important and different roles in the {{Wiki|history}} of Japanese-American [[Buddhism]] and that {{Wiki|ethnic}} divisions in different kinds of contemporary religiosity are related to both secularization and spiritualization of [[Buddhism]]. | ||

Japanese-American [[Buddhism]] in Paia | Japanese-American [[Buddhism]] in Paia | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In the 1930s the majority of the 10,000 citizens of Paia on the island’s north coast were | + | The first {{Wiki|Japanese}} came to [[Hawaii]] as a part of the [[Hawaii]] labor program (kan’yaku imin, |

| + | 1885–1894). A total of twenty-six ships brought 29,069 government contract [[people]], followed by approximately 125,000 “free migrants” in the period from 1894 to 1908 (Ama, 2011: 32). Until 1924, approximately 220,000 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|Japanese}} arrived from [[Japan]], most of whom would to some extent be affiliated to [[Buddhism]]. The import of “picture brides”3 helped produce descendants, and in 1920, second-generation {{Wiki|Japanese}} comprised | ||

| + | |||

| + | almost half of the {{Wiki|Japanese}} population (Odo, 2004: 37), constituting a “{{Wiki|Japanese}} village in the Pacific” ([[Tanabe]], 2005: 82). The first phase was characterized primarily by {{Wiki|individuals}} leaving | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Japan]] in search of better living standards as workers in the Hawaiian sugar plantations. Although both the {{Wiki|Japanese}} and the Hawaiian governments initially intended the immigrant workers to return to [[Japan]], almost half of them became long-term settlers, constituting a new {{Wiki|diaspora}} {{Wiki|community}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In the 1930s the majority of the 10,000 citizens of Paia on the island’s [[north]] coast were | ||

{{Wiki|Japanese}} (Duensing, 1998: ix), and schools, hospitals, markets, stores, restaurants, a | {{Wiki|Japanese}} (Duensing, 1998: ix), and schools, hospitals, markets, stores, restaurants, a | ||

| + | |||

[[File:14japan.6.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:14japan.6.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | 2 Fieldwork was carried out for two months (autumn 2009, summer 2010, and autumn 2011) in Paia. For comparative [[reasons]], fieldwork was carried out for one month (summer 2010) in Honolulu on the island of Oahu. Apart from participant observation (formal [[rituals]] and {{Wiki|social}} gatherings at the [[temples]]), interviews were conducted with Japanese-American [[Buddhists]] in Maui in the Hawaiian [[form]] of “talking stories”. In all, thirty-eight {{Wiki|individuals}} were interviewed in and around Paia and twelve in Honolulu. Moreover, interviews were conducted with representatives of other [[religious]] groups on Maui and Oahu to gather mainly quantitative {{Wiki|data}} on membership and affiliation throughout the years, while textual material like newsletters, [[temple]] records, and [[books]] from [[temples]] and libraries were used primarily to support investigations of the historical [[dimension]] of the project. | + | 2 Fieldwork was carried out for two months (autumn 2009, summer 2010, and autumn 2011) in Paia. For comparative [[reasons]], fieldwork was carried out for one month (summer 2010) in [[Honolulu]] on the [[island]] of Oahu. Apart from |

| + | |||

| + | participant observation (formal [[rituals]] and {{Wiki|social}} gatherings at the [[temples]]), interviews were conducted with Japanese-American [[Buddhists]] in [[Maui]] in the Hawaiian [[form]] of “talking stories”. In all, thirty- | ||

| + | |||

| + | eight {{Wiki|individuals}} were interviewed in and around Paia and twelve in [[Honolulu]]. Moreover, interviews were conducted with representatives of other [[religious]] groups on [[Maui]] and Oahu to [[gather]] mainly quantitative | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|data}} on membership and affiliation throughout the years, while textual material like newsletters, [[temple]] records, and [[books]] from [[temples]] and libraries were used primarily to support investigations of the historical [[dimension]] of the project. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

3 Often, the only way for {{Wiki|Japanese}} (and [[Korean]]) plantation workers to find a spouse from their | 3 Often, the only way for {{Wiki|Japanese}} (and [[Korean]]) plantation workers to find a spouse from their | ||

| − | homelands was to select one on the basis of photographs or through family recommendations. | + | homelands was to select one on the basis of photographs or through [[family]] recommendations. |

| + | theater, and immigrant camps gave the small town a lively {{Wiki|touch}} of {{Wiki|Japanese}} commerce and {{Wiki|culture}} (ibid., vii). “Nearly all participated in a diversity of [[sports]] programs and attended one of several [[Buddhist]], [[Shinto]], {{Wiki|Protestant}} and {{Wiki|Catholic}} churches in the area” (Bartholomew, 1994: 109). Also two [[Zen]] [[Buddhist]] | ||

| + | [[temples]] were established by the immigrants, later giving the {{Wiki|Japanese}} mother organizations a prospect of [[Hawaii]] [[being]] a [[religious]] frontier in a general “eastward [[transmission]] of [[Buddhism]]” ([[Williams]] and {{Wiki|Moriya}}, 2010: ix). In 1904, the S6t6 [[Zen]] [[Buddhist]] [[priest]] Sokyo Ueoka arrived in [[Honolulu]] from | ||

| − | + | {{Wiki|Hiroshima}}, having “received an assignment to become a visiting [[minister]] to | |

{{Wiki|Japanese}} immigrants in Hawaii.”4 In 1906, “upon the request of the {{Wiki|Japanese}} residents | {{Wiki|Japanese}} immigrants in Hawaii.”4 In 1906, “upon the request of the {{Wiki|Japanese}} residents | ||

| − | in | + | in [[Maui]]” (ibid.), the Paia Mantokuji [[Soto]] [[Mission]] was built as a sub-temple to its {{Wiki|Japanese}} mother |

| + | |||

| + | temple.5 The first [[priest]] soon expanded the congregation, not least because he was well-known among the locals for curing the sick through [[prayer]] and for causing [[rain]] after periods of drought. In 1935, the [[Rinzai]] [[Zen]] [[Mission]] (hereafter RZM) was established with financial support from the {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[organization]] in the | ||

| + | |||

| + | outskirts of Paia.6 This is the only foreign [[mission]] [[temple]] of the [[Rinzai school]] and the central [[temple]] for the group of Okinawan immigrants who still constitute approximately 15 percent of the {{Wiki|ethnic}} category “{{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]]” in [[Hawaii]] today. Children of the first immigrants vividly “talk story” of how the | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[temples]] have come to [[function]] as [[religious]] and {{Wiki|cultural}} {{Wiki|community}} centers for those of the town’s and the island’s inhabitants who have ties to [[Japan]] and Okinawa. Such stories might be related to the [[Sunday school]], {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[flower]] arrangement and [[tea ceremony]] classes, the scout and youth groups, the sewing school, | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | the [[chanting]] groups (goeika), or the women’s associations (fujinkai), all of which were part of the [[glue]] binding the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|community}} together, like a “[[lotus]] in [[paradise]]” ([[Tanabe]], 2000), until just a few decades ago. | ||

| + | |||

| − | While the 1920 sugar strike involving {{Wiki|Japanese}} workers made some commentators accuse [[Buddhists]] of [[being]] a threat to American {{Wiki|society}} (Tanabe, 2000: 1), the major turning point for all {{Wiki|Japanese}} in Hawaii was Pearl Harbor and [[World]] [[War]] II. As it was difficult and, in the long run, impossible to place almost half of the population in internment camps, certain community leaders, school [[teachers]], and [[Buddhist]] and [[Shinto]] priests were sent to internment camps on the mainland.7 [[Buddhism]] became the [[religion]] of the enemy (Odo, 2004: 98), and [[conversion]] to the majority [[religion]], {{Wiki|{{Wiki|Christianity}}}}, became even more widespread as did the custom of intermarriage with non-Japanese. Some of the core members of the two Paia [[temples]] were even forced by their parents to go to {{Wiki|Christian}} churches. After the [[War]], Paia became less and less {{Wiki|Japanese}}. Workers in the sugar plantations were [[offered]] new apartments in the modern “[[Dream]] City” in neighboring Kahului. Many migrated to other islands, to Honolulu, or | + | While the 1920 sugar strike involving {{Wiki|Japanese}} workers made some commentators accuse [[Buddhists]] of [[being]] a threat to [[American]] {{Wiki|society}} ([[Tanabe]], 2000: 1), the major turning point for all {{Wiki|Japanese}} in [[Hawaii]] was {{Wiki|Pearl Harbor}} and [[World]] [[War]] II. As it was difficult and, in the long run, impossible to place |

| − | the mainland to work or get an education, and in the 1970s the very [[existence]] of the village was threatened. | + | |

| + | almost half of the population in internment camps, certain {{Wiki|community}} leaders, school [[teachers]], and [[Buddhist]] and [[Shinto]] {{Wiki|priests}} were sent to internment camps on the mainland.7 [[Buddhism]] became the | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[religion]] of the enemy (Odo, 2004: 98), and [[conversion]] to the majority [[religion]], {{Wiki|{{Wiki|Christianity}}}}, became even more widespread as did the {{Wiki|custom}} of intermarriage with non-Japanese. Some of | ||

| + | |||

| + | the core members of the two Paia [[temples]] were even forced by their [[parents]] to go to {{Wiki|Christian}} churches. After the [[War]], Paia became less and less {{Wiki|Japanese}}. Workers in the sugar plantations were [[offered]] new apartments in the {{Wiki|modern}} “[[Dream]] City” in neighboring Kahului. Many migrated to other islands, to [[Honolulu]], or | ||

| + | the mainland to work or get an [[education]], and in the 1970s the very [[existence]] of the village was threatened. | ||

[[File:2240.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:2240.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Then the hippies arrived, changing the outlook and the {{Wiki|atmosphere}}. The old dwellers felt [[contempt]] toward the newcomers' strange {{Wiki|behavior}} and counterculture ideas, but could not avoid appreciating the fact that they actually helped Paia survive. Some hippies, as several of those who remained in Maui called themselves, came to Paia for [[spiritual]] [[reasons]] and stayed to participate in what later became [[Buddhist]] groups. As early as 1959 Robert Aitken (1917–2010) started his [[Zen]] group in Honolulu, and in 1969 he moved to Maui to set up the Maui Zendo. After Aitken and his [[Diamond]] [[Sangha]] had moved back to Honolulu, the Maui Zendo remained a local subgroup with [[meditation]] sessions and occasional [[retreats]] in private homes. In 1974 a [[Tibetan]] [[Dharma]] Center was established in Paia. A permanent resident [[lama]], visiting [[lamas]], and a few residing lay [[Buddhists]] [[live]] in the center today. They have their own worship hall, [[stupa]], garden, and a shop with [[religious]] paraphernalia. In the 1980s and 1990s surfers and tourists came in large numbers, once again changing the [[spirit]] of the town. Within the last decade, a rapidly growing holistic milieu has entered Paia and the neighboring Haiku area. Services and [[people]] come and go in this very fluid community, the demography of which has also changed dramatically in the last decades. According to the 2010 U.S. census, 2,668 [[people]] [[live]] in the area, 7 percent of whom define themselves as Japanese.8 | + | |

| + | |||

| + | Then the hippies arrived, changing the outlook and the {{Wiki|atmosphere}}. The old dwellers felt [[contempt]] toward the newcomers' strange {{Wiki|behavior}} and counterculture [[ideas]], but could not avoid appreciating the fact that they actually helped Paia survive. Some hippies, as several of those who remained in [[Maui]] called themselves, came to | ||

| + | |||

| + | Paia for [[spiritual]] [[reasons]] and stayed to participate in what later became [[Buddhist]] groups. As early as 1959 {{Wiki|Robert Aitken}} (1917–2010) started his [[Zen]] group in [[Honolulu]], and in 1969 he moved to [[Maui]] to set up the [[Maui Zendo]]. After [[Aitken]] and his [[Diamond]] [[Sangha]] had moved back to [[Honolulu]], the [[Maui Zendo]] remained a local | ||

| + | |||

| + | subgroup with [[meditation]] sessions and occasional [[retreats]] in private homes. In 1974 a [[Tibetan]] [[Dharma]] [[Center]] was established in Paia. A [[permanent]] resident [[lama]], visiting [[lamas]], and a few residing lay [[Buddhists]] [[live]] in the center today. They have their [[own]] {{Wiki|worship}} hall, [[stupa]], [[garden]], and a shop with | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[religious]] {{Wiki|paraphernalia}}. In the 1980s and 1990s surfers and tourists came in large numbers, once again changing the [[spirit]] of the town. Within the last decade, a rapidly growing {{Wiki|holistic}} {{Wiki|milieu}} has entered Paia and the neighboring Haiku area. Services and [[people]] come and go in this very fluid {{Wiki|community}}, the demography of which has | ||

| + | |||

| + | also changed dramatically in the last decades. According to the 2010 [[U.S.]] census, 2,668 [[people]] [[live]] in the area, 7 percent of whom define themselves as Japanese.8 | ||

Ethnified and de-ethnified [[Japanese Buddhism]] | Ethnified and de-ethnified [[Japanese Buddhism]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | Cultural origin is clearly an important [[element]] in both of the two [[Zen]] [[temples]]. The architecture of the present main buildings is typical of the [[traditional]] or simplified {{Wiki|Japanese}} style [[temples]], which especially in the islands “up until the 1970s and 1980s […] bustled with youth groups, women’s organizations, baseball teams, scout troops, [[language]] classes, and other | + | The question of how and to what extent ethnicity should be part of [[religious]] identity—and vice versa—has constituted a challenge for the Japanese-Americans who [[live]] in Paia and on the rest of the Hawaiian Islands for the {{Wiki|past}} 100 years. Some aspects have been [[consciously]] chosen or rejected, whereas others are [[signs]] of a less reflective response to {{Wiki|social}} and material circumstances. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|Cultural}} origin is clearly an important [[element]] in both of the two [[Zen]] [[temples]]. The [[architecture]] of the {{Wiki|present}} main buildings is typical of the [[traditional]] or simplified {{Wiki|Japanese}} style [[temples]], which especially in the islands “up until the 1970s and 1980s […] bustled with youth groups, women’s organizations, | ||

| + | |||

| + | baseball teams, scout troops, [[language]] classes, and other [[activities]]” ([[Tanabe]] and [[Tanabe]], forthcoming: 20). Also typical for the two [[temples]] are the [[gardens]], the [[temple]] [[bells]], and the graveyards, the oldest of | ||

| + | |||

| + | which contain {{Wiki|Chinese}} characters and/or {{Wiki|Japanese}} names.9 In the interior there are [[altars]], [[statues]], [[Buddha]] figures and [[bodhisattvas]], offertory boxes, [[sutra]] tables, [[bells]], [[wooden fish]], wooden [[ancestor]] tablets, and photographs of former {{Wiki|priests}} and | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The most obvious [[characteristic]] of an {{Wiki|ethnic}} [[religion]] from both [[temples]] is—as has been the case throughout history—the ethnicity of their visitors, users, and members. Although its users are not exclusively | ||

| + | |||

| + | Japanese-American, as is the case in other non-Zen [[temples]] (where the absence of [[meditation]] makes it even more difficult to attract non-Japanese), mono-ethnicity is the norm. The two Paia [[temples]] do occasionally attract Caucasians, but by far the majority of their participants remain of {{Wiki|Japanese}} origin, | ||

| + | |||

| + | as are the visiting {{Wiki|priests}}, [[monks]], professors, and students from [[temples]], [[monasteries]], and [[universities]] in [[Japan]]. Some have grown up in the vicinity of the [[temples]], and the presence of the large Ueoka [[family]] in Mantokuji is a [[visible]] sign of a living [[tradition]] based on a core of [[family]] heritage. How | ||

| + | |||

| + | to get the younger generations involved in the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|church}} {{Wiki|community}} is an important issue [[being]] discussed in all congregations, and many have [[activities]] directly related to these matters.11 However, [[traditional]] [[temple]] [[activities]] do in fact attract a few young [[people]] who are searching for their | ||

| + | “ancestral ties” and who see the [[temples]] as concrete [[manifestations]] of an [[imaginary]] [[Japan]]. One [[person]] even described her turn from [[Tibetan Buddhism]] to {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[temple]] [[Buddhism]] as a way to “connect to my {{Wiki|Japanese}} side.”12 | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Other members have been on [[religious]] and {{Wiki|cultural}} [[pilgrimage]] tours to [[Japan]], and the {{Wiki|priests}} are sent to {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[monasteries]] to learn to [[chant]] the [[sutras]] and perform the [[rituals]] in the correct {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[manner]]. Both [[temples]] have been involved in fundraising [[activities]] in the wake of the | |

| + | |||

| + | tsunami/earthquake in 2011, and the [[minister]] at RZM even went to [[Japan]] for three months to do voluntary work for his country of origin. The major yearly [[religious]] and {{Wiki|cultural}} {{Wiki|festivals}}, such as the [[hanamatsuri]], [[shichi-go-san]], and obon,13 are performed just like in [[Japan]], and also in Paia the [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] are said to | ||

| + | |||

| + | “preserve a [[religion]] for {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[family]] ancestry” ([[Tanabe]], 2005: 94). In a certain [[sense]], “the {{Wiki|Japanese}} religiosity values and [[beliefs]] brought by the [[Issei]] and transferred to the later generations continue to have [[merit]]” (Kashima, 2008: 122). Especially the Okinawan {{Wiki|culture}} is kept alive at the RZM. Each year | ||

| + | |||

| + | during the obon summer {{Wiki|festival}}, thousands of visitors welcome and {{Wiki|honor}} their {{Wiki|ancestors}}, and [[lion]] dances and [[sanshin]] tunes are represented and performed by the Okinawan {{Wiki|Cultural}} [[Center]], demonstrating close relations to Okinawa. “For me, there has always been a [[connection]] between | ||

[[File:420 japan.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:420 japan.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Okinawan culture and the RZM. I never [[thought]] of why I was a [[Buddhist]],” one informant said. Another mistakenly [[thought]] that [[Rinzai]] [[Zen]] was Okinawan. Visitors from [[Japan]], on the other hand, told me | + | Okinawan {{Wiki|culture}} and the RZM. I never [[thought]] of why I was a [[Buddhist]],” one informant said. Another mistakenly [[thought]] that [[Rinzai]] [[Zen]] was Okinawan. Visitors from [[Japan]], on the other hand, told me |

| − | + | that they find the obon {{Wiki|celebrations}} in [[Hawaii]] much more [[Wikipedia:Authenticity|authentic]] {{Wiki|Japanese}} than the ones held in [[Japan]]. The conservative preserving [[character]] displayed in highlighting or even constructing authenticity in {{Wiki|diaspora}} contexts is a well-known [[phenomenon]] in {{Wiki|cultural}} and [[religious]] studies (Lindholm, 2008; Roy, 2010). | |

| − | + | However, there are equally clear [[signs]] of a de-ethnified [[religion]]. The Americanization and de-Japanization efforts were strengthened after the [[War]], but attempts were also made early in the immigration period to merge | |

| + | with the local and {{Wiki|Western culture}}, balancing the {{Wiki|ethnic}} [[elements]] of the diaspora.14 The photographic archive of the old [[temples]] gives one a [[sense]] of this, as images of formally dressed members gradually give way to images of [[people]] in “aloha style” dress, displaying the {{Wiki|communication}} {{Wiki|codes}} of contemporary | ||

| − | Crises and decline | + | members, i.e., giving hugs, wearing shorts and aloha shirts are more natural than [[bows]], {{Wiki|kimonos}}, and suits. It is evident from the way in which the {{Wiki|Japanese}} and Okinawan {{Wiki|cultural}} associations have cut the ties with the [[temples]], resorting to formal relations only on special occasions.15 And it is evident from the long process of |

| + | |||

| + | Protestantization via which the adoption of a {{Wiki|Christian}} {{Wiki|culture}} has colored both the [[rituals]] and the [[organization]]. As has become standard in most [[temples]], the {{Wiki|worship}} hall in one of the two [[Zen]] [[temples]] with a “Hawaiian eclectic style” (Ama, 2011: 100) contains pews and a lectern. The “[[sermons]]” are given by a | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | “[[minister]],” the “hymns” are chanted in English, accompanied by Psalm [[books]] and an {{Wiki|organ}}. {{Wiki|Christmas}} and Easter have been celebrated in one of the [[temples]] for decades, all announced in the English newsletters, and the [[existence]] of large shelves of [[books]] on [[Buddhism]] (mostly written in English) in one of the [[temples]], | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | even though the [[books]] are seldom read, suggests a certain {{Wiki|Protestant}} [[idea]] of a [[religious]] core of written materials. The [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Buddhist]] [[temple]] parishioner system ([[danka seido]]) has been “congregationalized” in [[Hawaii]] with membership, boards of trustees for organizational {{Wiki|management}}, and structured | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Sunday]] services. As it has been the case in other {{Wiki|processes}} of {{Wiki|modern}} Protestantization of Buddhism,16 the laity in one [[sense]] has thus been institutionally [[empowered]] at the expense of the {{Wiki|clergy}}, who is still respected as [[ritual]] specialists and [[religious]] officials, but with less actual authority. While marveling at [[Hawaii]] as | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | a romantic snapshot of old [[Japan]], other {{Wiki|Japanese}} visitors accuse the [[traditions]] of [[being]] too Americanized. “They look down upon us,” one of the local [[temple]] attendants said. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The only [[temple]] [[activities]] that cater to non-Japanese [[Americans]] are [[taiko]] drumming and [[meditation]] ([[zazen]]). [[Taiko]] drumming has been kept alive and revived as a {{Wiki|cultural}} [[activity]] performed at obon ({{Wiki|festival}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | to {{Wiki|honor}} the [[spirits]] of the {{Wiki|ancestors}}), and at Mantokuji it is a periodical [[activity]] engaging both {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]] and Euro-Americans; the [[latter]] group is not involved in any other [[temple]] [[activity]]. [[Western]] adoption of especially [[Zen]] [[Buddhist meditation]] can be considered “{{Wiki|Protestant}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Zen]]” (Sharf, 1995a) in the way that inner, personal [[religious]] [[experience]] has been democratized beyond clerical [[mediation]], and its participation patterns also confirm the {{Wiki|ethnic}} divide. At Mantokuji most of the 180 [[people]] who have joined the [[meditation]] session at least once in the last eight years are | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Caucasians, and at RZM [[zazen]] has either been practiced by Euro-Americans or been managed by the (primarily Euro-American) [[Maui Zendo]]. In Paia, [[taiko]] drumming and [[zazen]] thus constitute two different [[forms]] of [[activities]], each expressing the {{Wiki|ethnic}} divisions in the “parallel congregations.” 17 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Crises and {{Wiki|decline}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The different ways in which ethnicity is [[manifested]] signify the plural and, to some extent, hybrid {{Wiki|cultural}} and [[religious]] [[reality]] of {{Wiki|diaspora}} religiosity in [[Hawaii]]. {{Wiki|Ethnic}} {{Wiki|representations}} also point to general developmental {{Wiki|tendencies}} of [[religious]] affiliation. If we ask those who Kashima refers to as {{Wiki|individuals}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | of [[belief]], there are [[signs]] that “the persistence of a high [[degree]] of [[Buddhism]] among {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]] continues today” (Kashima, 2008: 108).18 However, there is also {{Wiki|evidence}} to the contrary suggesting that | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[religion]] has declined in importance. Though [[religious]] demography is generally a tricky business and [[Buddhists]] are notoriously difficult to identify (Tweed, 2002; [[Borup]] forthcoming), indicators of a crisis in [[Japanese Buddhism]] seem so clear that different parameters unequivocally point to {{Wiki|secularizing}} {{Wiki|tendencies}} at both {{Wiki|individual}}, | ||

| − | |||

[[File:9837c.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:9837c.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | 17 [[Thus]], Hawaii generally reflects the division between Euro-American and Japanese-American [[Zen]] [[Buddhists]], as 90 percent of the former participate in [[meditation]] sessions (zazenkai) (Asai and Williams, 1999: 29–30) and regard [[meditation]] as the single most important [[activity]] within the [[Buddhist]] group (Colemann 2001, 119). See also Nagasawa 2011 for the same tendencies in San Francisco. Masatsugu claims that the {{Wiki|ethnic}} dividing lines were more fluid in the 1960s and | + | 17 [[Thus]], [[Hawaii]] generally reflects the [[division]] between Euro-American and Japanese-American [[Zen]] [[Buddhists]], as 90 percent of the former participate in [[meditation]] sessions (zazenkai) ([[Asai]] and [[Williams]], 1999: 29–30) and regard [[meditation]] as the single most important [[activity]] within the [[Buddhist]] group |

| − | 1970s (2008: 427). {{Wiki|Ethnic}} dividing lines are also seen on the main island of Hawaii, Oahu, among the [[Vietnamese]] population, where the Asian-American culture of [[Buddhism]] is not compatible with [[Thich Nhat Hanh]] inspired [[Buddhist meditation]], and where two parallel activities by two different groups take place in a [[Korean]] [[temple]]: Euro-Americans’ [[mindfulness]] [[meditation]] and {{Wiki|ethnic}} | + | |

| − | 18 Kashima, 2008, is referring to the results from the 1999–2000 Hawaii Survey, under the | + | (Colemann 2001, 119). See also Nagasawa 2011 for the same {{Wiki|tendencies}} in [[San Francisco]]. Masatsugu claims that the {{Wiki|ethnic}} dividing lines were more fluid in the 1960s and |

| − | [[direction]] of Professor Yasumasa Kuroda, based on interviews with 206 {{Wiki|Japanese}} Americans in southern Oahu. | + | 1970s (2008: 427). {{Wiki|Ethnic}} dividing lines are also seen on the main [[island]] of [[Hawaii]], Oahu, among the |

| + | |||

| + | [[Vietnamese]] population, where the Asian-American {{Wiki|culture}} of [[Buddhism]] is not compatible with [[Thich Nhat Hanh]] inspired [[Buddhist meditation]], and where two parallel [[activities]] by two different groups take place in a [[Korean]] [[temple]]: Euro-Americans’ [[mindfulness]] [[meditation]] and {{Wiki|ethnic}} [[Koreans]]’ {{Wiki|culture}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | religiosity. A Pew Forum survey shows that only 14 percent of Asian-American [[Buddhists]] [[meditate]] (Pew Research [[Center]], 2012: 19). While such {{Wiki|data}} could be said to be illustrative of a "degenerate" {{Wiki|folk}} [[Buddhism]], it could equally be said to express typical {{Wiki|modern}} [[Buddhism]] or a Westernized "invented" | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[tradition]], with [[meditation]] [[being]] a core practice of all [[Buddhism]]. Historically, lay [[Buddhists]] have never been expected to practice [[meditation]], which [[traditionally]] is an {{Wiki|elite}} [[ritual]] conducted by [[monks]] and {{Wiki|priests}}. On {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Zen]] [[Buddhist]] [[zazen]], see [[Borup]], 2008: 205–216. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 18 Kashima, 2008, is referring to the results from the 1999–2000 [[Hawaii]] Survey, under the | ||

| + | [[direction]] of [[Professor]] Yasumasa Kuroda, based on interviews with 206 {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]] in southern Oahu. | ||

| − | institutional, and societal levels. According to Tanabe, “[[Japanese Buddhism]] in Hawai’i for the last thirty years has been [[suffering]] a slow but certain [[death]]” (2005: 78).19 “The [[temple]] has no future,” one informant from the RZM commented while pointing to the ocean, which has symptomatically consumed several meters of the nearby shore. | + | institutional, and societal levels. According to [[Tanabe]], “[[Japanese Buddhism]] in [[Hawai’i]] for the last thirty years has been [[suffering]] a slow but certain [[death]]” (2005: 78).19 “The [[temple]] has no {{Wiki|future}},” one informant from the RZM commented while pointing to the ocean, which has symptomatically consumed several meters of the nearby shore. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | First of all, the demographic context frames the situation in Paia and on [[Maui]]. As mentioned, there are simply fewer [[people]] of {{Wiki|Japanese}} origin living in local communities.20 A lack of career possibilities has increased periodic or [[permanent]] migration to [[Honolulu]] or the mainland, and recent decades have witnessed an [[influx]] of mainlanders and foreigners. The number of out-marriages and conversions has increased, and as a part of a general tendency among Asian-Americans, fewer identify | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 19 Tracing such claims of crises in a historical {{Wiki|perspective}} based on [[religious]] demography is of course challenging. Because membership is a [[doubtful]] indicator of [[religious]] [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] and engagement, because there is a general lack of reliable {{Wiki|data}} on [[religious]] affiliation in [[Hawaii]], and because the | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[traditions]] lose their affiliation to [[religious]] {{Wiki|institutions}}, figures are, at best, an estimate. [[Tanabe]] writes that by 1931, 12,800 children were studying in 125 [[Buddhist]] [[Sunday]] schools throughout the islands ([[Tanabe]] 2005, 90). In 1958 Hormann, [[consciously]] {{Wiki|aware}} of the “woefully inadequate” [[information]], | ||

| + | |||

| + | refers to {{Wiki|Japanese}} leaders, suggesting that there are “125,000 or more” [[Buddhists]] in [[Hawaii]], [[corresponding]] to 70 percent of the {{Wiki|Japanese}} population, | ||

| + | 62,000 of which are “active followers” (Hormann, 1958: 5). A few years later, he suggests that the figure is “above | ||

| + | |||

| + | 150,000” (Hormann, 1961–1962: 62). Schmitt refers to {{Wiki|data}} from 1972, listing 15.4 percent of the population (120,000) as members of [[Buddhist]] churches, compared to 24 percent (40,000) in 1905 and 12 percent (62,000) in 1954-1955 (Schmitt, 1973: 44 and 46). The [[State]] of [[Hawaii]] {{Wiki|Data}} [[Book]] 2001 | ||

| + | |||

| + | (http://hawaii.gov/dbedt/info/economic/databook/db2001/sec01.pdf) lists 9 percent of the population (110,000), whereas the Pew Forum in 2010 found that 6 percent (82,000) of Hawaiians are [[Buddhists]] (http://religions.pewforum.org/maps). The [[president]] of the [[Hawaii]] Association of [[Buddhists]] believes that there | ||

| + | |||

| + | are approximately 100,000 [[Buddhists]] (or 8-10 percent of the population) in [[Hawaii]], many of whom are {{Wiki|Japanese}} (personal [[conversation]]), an estimate that is close to the 91,697 [[Buddhists]] reported in the [[U.S.]] [[Religion]] Census (http://www.rcms2010.org/), where “congregational {{Wiki|adherents}} include all full members, | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | their children, and others who regularly attend services. The total number of {{Wiki|adherents}} reported by the [[religious]] groups listed above (561,980) included 41.3 percent of the total population in 2010” (ibid.). In 2005 [[Tanabe]] (2005: 77) suggested that there is only approximately 20,000 [[Buddhists]] in [[Hawaii]] today, compared to 50,000 in the early | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 1960s. In a more recent publication ([[Tanabe]] and [[Tanabe]] forthcoming), this figure seems to hold. By visiting each of the 90 Japanese-American [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] ([[excluding]] S6ka Gakkai centers) throughout the [[island]], the authors have come up with the figure of 19,640 formal members (9,820 families). There were thus 1,846 {{Wiki|individuals}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | or 948 families in [[Maui]] alone. “These numbers were provided by [[temples]] themselves, though many admit that their numbers are best estimates. [[Temples]] count members by families, and we have multiplied their reported numbers by two, which ministers and lay leaders agreed was the best way to estimate the number of {{Wiki|individuals}} formally | ||

| − | |||

| + | belonging to [[temples]]. Obviously this is an approximation, but no one has asked each [[temple]] as we have, though we suspect that the actual number is higher” (ibid.: xiii). | ||

| + | 20 In 1900 40,000 [[people]] were living in [[Maui]]; a hundred years later the figure was 134,000. | ||

| − | + | Nearly 14,000 of these identify themselves as {{Wiki|Japanese}}, [[corresponding]] to 10 percent of the population (http://hawaii.gov/dbedt/info/economic/databook/db2004/section01.pdf). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Nearly 14,000 of these identify themselves as {{Wiki|Japanese}}, corresponding to 10 percent of the population (http://hawaii.gov/dbedt/info/economic/databook/db2004/section01.pdf). | ||

[[File:Bangkok 0.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bangkok 0.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | themselves with only one {{Wiki|ethnic}} or racial category.21 A decrease in mono-ethnic identity does not necessarily lead to a decrease in [[religious]] belonging or commitment. The continuation of—and, in some instances, even increased participation in—traditional {{Wiki|Japanese}} cultural and [[religious]] festivals (such as the obon) is a sign of a [[tradition]] that is [[being]] kept alive or has been revived.22 A few {{Wiki|Japanese}} Americans actually come to the [[temples]] as newcomers, either to explore their cultural [[roots]] or to pursue [[spiritual]] interests, but the distance between the {{Wiki|Japanese}} Americans who have maintained a close connection to {{Wiki|Japanese}} culture and the {{Wiki|Japanese}} Americans who incorporate some kind of [[psychological]] connection to a “[[spiritual]] homeland” via a “[[symbolic]] ethnicity” (Okamura 2008, 135) has grown, from generation to generation. | + | themselves with only one {{Wiki|ethnic}} or racial category.21 A {{Wiki|decrease}} in mono-ethnic [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] does not necessarily lead to a {{Wiki|decrease}} in [[religious]] belonging or commitment. The continuation of—and, in some instances, even increased participation in—traditional {{Wiki|Japanese}} {{Wiki|cultural}} and [[religious]] {{Wiki|festivals}} (such |

| + | |||

| + | as the obon) is a sign of a [[tradition]] that is [[being]] kept alive or has been revived.22 A few {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]] actually come to the [[temples]] as newcomers, either to explore their {{Wiki|cultural}} [[roots]] or to pursue [[spiritual]] interests, but the distance between the {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]] who have maintained a close | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[connection]] to {{Wiki|Japanese}} {{Wiki|culture}} and the {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]] who incorporate some kind of [[psychological]] [[connection]] to a “[[spiritual]] homeland” via a “[[symbolic]] ethnicity” (Okamura 2008, 135) has grown, from generation to generation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Whereas some [[temples]] have [[experienced]] a dramatic {{Wiki|decrease}} in the number of donating members, the {{Wiki|decrease}} at the RZM and Mantokuji has only been moderate. [[Temple]] records show that, some decades ago or before | ||

| + | |||

| + | the [[War]], [[attendance]] was not always as high as one imagines. Another [[characteristic]] feature, as revealed by interviews, is that children brought up by former ministers at the two [[temples]] did not have a [[religious]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[education]] nor [[experience]] in [[meditation]]; one of them even confessed to [[knowing]] [[nothing]] about [[Zen]] and [[Buddhism]]. Regardless of the commitment of a number of {{Wiki|priests}} who work hard to keep [[temple]] religiosity active, there has been a {{Wiki|decrease}} in both [[attendance]] and commitment throughout the last few decades.23 Members have | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 21 The number of [[Americans]] who identify themselves as “{{Wiki|Asian}} and one or more other races” increased by 72.2 percent from the 1990 to the 2000 census (http://www.census.gov/population/cen2000/atlas/censr01-108.pdf). The [[U.S.]] {{Wiki|Asian}} population includes at least 30 {{Wiki|ethnic}} groups, and 4.2 percent of the [[U.S.]] population reported that | ||

| − | + | they consider themselves {{Wiki|Asian}} (http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/c2kbr01-16.pdf). According to the 2010 census, the number of Asian-Americans has increased the least in [[Hawaii]] (http://2010.census.gov/2010census/data/index.php), where 35 percent identify themselves as [[Asians]] only, 14.7 percent as {{Wiki|Japanese}} only. | |

| − | |||

22 Already in the RZM Newsletter from January 1994, the discrepancy between general crises | 22 Already in the RZM Newsletter from January 1994, the discrepancy between general crises | ||

| − | and the success of single activities was [[acknowledged]]: “Gradually we are losing members of our [[temple]] and we [[feel]] the loneliness of this so I must [[stress]] to you to take care of yourselves day to day to [[live]] a long & active [[life]] in this coming year […] Every year [[Buddhism]] in Hawaii decreases, but our annual activities are not diminishing in numbers or importance. This shows that [[Buddhism]] is still a [[vital]] [[religion]] in Hawaii.” | + | and the [[success]] of single [[activities]] was [[acknowledged]]: “Gradually we are losing members of our [[temple]] and we [[feel]] the loneliness of this so I must [[stress]] to you to take [[care]] of yourselves day to day to [[live]] a long |

| − | 23 Membership, donations, and attendance have been sporadically registered throughout the | + | |

| + | & active [[life]] in this coming year […] Every year [[Buddhism]] in [[Hawaii]] {{Wiki|decreases}}, but our annual [[activities]] are not diminishing in numbers or importance. This shows that [[Buddhism]] is still a [[vital]] [[religion]] in [[Hawaii]].” | ||

| + | 23 Membership, {{Wiki|donations}}, and [[attendance]] have been sporadically registered throughout the | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

years. At Mantokuji, there were 580 donors in 1970, in the 2000s the figure was around 200. By | years. At Mantokuji, there were 580 donors in 1970, in the 2000s the figure was around 200. By | ||

| − | 2010 there were 130 paying members, which according to the priest included both active and non-active members, as the number of donors also includes [[people]] who attend a [[funeral]], but have no other relation to the [[temple]]. Three hundred and thirty [[people]] are on the mailing list, some of whom are also non-members from the mainland. The large Ueoka family, descendants of the first [[temple]] family, still contributes significantly to the upkeep of the [[temple]]. In 2010 the RZM had 100 paying members, 10–15 of which were considered active members, periodically attending the fortnightly ceremony. Another 100 [[people]] are considered donors, some of whom are also among the 1000 [[people]] who join the large obon summer festival. A newsletter is sent to | + | 2010 there were 130 paying members, which according to the [[priest]] included both active and non-active members, as the number of donors also includes [[people]] who attend a [[funeral]], but have no other [[relation]] to the [[temple]]. |

| − | 150 [[people]] in Hawaii and another 25 in [[Japan]]. As there were 121 dues-paying members and 360 donors in 1988, the decrease has only been moderate, compared to the future prospects of the | + | |

| + | |||

| + | Three hundred and thirty [[people]] are on the mailing list, some of whom are also non-members from the mainland. The large Ueoka [[family]], descendants of the first [[temple]] [[family]], still contributes significantly to the upkeep of the [[temple]]. In 2010 the RZM had 100 paying members, 10–15 of which were considered active members, periodically | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | attending the fortnightly {{Wiki|ceremony}}. Another 100 [[people]] are considered donors, some of whom are also among the 1000 [[people]] who join the large obon summer {{Wiki|festival}}. A newsletter is sent to | ||

| + | 150 [[people]] in [[Hawaii]] and another 25 in [[Japan]]. As there were 121 dues-paying members and 360 donors in 1988, the {{Wiki|decrease}} has only been moderate, compared to the {{Wiki|future}} prospects of the | ||

[[File:Bodhisena.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bodhisena.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | been scattered throughout the islands and the rest of the [[world]], and many [[feel]] obliged to remain a donor as long as graveyards are kept or older generations are alive. A longstanding member of the RZM illustrated this general [[attitude]] and tendency. He comes to the [[temple]] only to take care of his | + | been scattered throughout the islands and the rest of the [[world]], and many [[feel]] obliged to remain a {{Wiki|donor}} as long as graveyards are kept or older generations are alive. A longstanding member of the RZM illustrated this |

| + | |||

| + | general [[attitude]] and tendency. He comes to the [[temple]] only to take [[care]] of his {{Wiki|ancestors}}’ grave and out of loyalty to his old mother, and although he does complain about young people’s lack of adherence to [[tradition]], he | ||

| + | |||

| + | claims to have no [[interest]] in [[Buddhism]] at all. Few new members have joined in recent decades. [[Sunday]] schools, classes in {{Wiki|Japanese}}, [[flower]] arrangement, [[tea ceremony]], and youth groups are (as in most [[temples]]) | ||

| + | |||

| + | long gone. Symptomatically, even a typical [[religious]] [[activity]] like meeting to [[chant]] [[Buddhist]] hymns (goeika) is dying out at the temples—concurrently with the [[ageing]] of their members. Also in a broader Hawaiian {{Wiki|perspective}} the {{Wiki|tendencies}} are clear, and the deserted graveyards throughout the islands are living [[proof]] of | ||

| + | |||

| + | a dying [[tradition]]. A few [[temples]] have been converted into [[spiritual]] centers (‘studios’) or [[Tibetan Buddhist]] centers, both of which typically cater to only Euro-Americans. Others have had to close down, and many more are likely to do the same in the years to come, as there are too few donating members to keep the [[temples]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | alive financially and too few active participants to keep them alive [[spiritually]]. Some regions also [[experience]] a lack of ministers. As a career choice it is simply too risky; some young {{Wiki|males}} who are set to inherit their father’s [[temple]] are encumbered with too little [[symbolic]] capital or too many obligations, as is | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | the case with the current [[priest]] at Mantokuji, who is going to take over his father-in-law’s [[temple]] in [[Japan]]. Some services are called off, transferred, or [[transformed]] due to these circumstances. The crematorium at Mantokuji has been abandoned and moved to a [[non-Buddhist]] crematorium in a nearby town, and the many | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[traditional]] [[death]] [[rituals]] and memorial services have in both [[temples]] been either neglected or compressed into one day “all in one” {{Wiki|ceremony}}, after which there are no memorial [[rites]] to keep generational ties | ||

| + | |||

| + | alive. The practice of visiting the homes of [[temple]] members to conduct memorial [[rites]] (tanagyô) is either restricted to a few short visits (Mantokuji) or given up entirely (RZM). Most visits today are to older [[people]] at the home for senior citizens. | ||

[[Reasons]] for the crises in Japanese-American [[Buddhism]] | [[Reasons]] for the crises in Japanese-American [[Buddhism]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | [[Thus]], a parallel development for [[Japanese Buddhism]] in Hawaii is not surprising, although different cultural and historical contexts and developments also point to alternative explanations. The [[reasons]] for the crises are manifold and complex, but can be compressed into four interrelated aspects that are related to [[religion]] and ethnicity and concretely [[visible]] in Paia and in general throughout Hawaii. | + | Although “the process of secularization in [[Japan]] has a {{Wiki|distinctive}} pattern of its [[own]]” (Mullins, 2012: 62), it is still plausible to characterize the {{Wiki|decreasing}} significance of religion—in its different levels, phases, and with varying power—as some kind of secularization (Reader, 2012; Nelson, 2012). |

| + | |||

| + | [[Thus]], a parallel [[development]] for [[Japanese Buddhism]] in [[Hawaii]] is not surprising, although different {{Wiki|cultural}} and historical contexts and developments also point to alternative explanations. The [[reasons]] for the crises are manifold and complex, but can be compressed into four {{Wiki|interrelated}} aspects that are related to [[religion]] and ethnicity and concretely [[visible]] in Paia and in general throughout [[Hawaii]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[religion]], whose members are in their seventies, eighties, and nineties. Talks with {{Wiki|priests}} from other denominations in both [[Maui]] and [[Honolulu]] reveal a drop in membership within the last 30 years of up to 50 percent or more. | ||

| + | |||

| + | a. {{Wiki|Decreasing}} relevance of {{Wiki|ethnic}} [[religion]] | ||

| + | [[File:Buddha Jap.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | Ethno-religious [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] and de-ethnification strategies of {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]] throughout the {{Wiki|USA}} are closely related to the [[time]] of [[War]] and the aftermath hereof. However, apart from this particularistic context, developments also follow more general patterns comparable to other contexts. First of all, the | ||

| + | [[religious]] crisis is a consequence of the {{Wiki|social}} [[development]] from agrarian to industrial and now post-industrial {{Wiki|societies}}. Early immigrants needed a {{Wiki|stable}}, [[symbolic]] presence, a [[spiritual]] homeland, a communal [[space]] for first concrete and later [[imagined]] [[roots]] to [[Japan]]. [[Temples]] were | ||

| − | [[ | + | places for [[religious]] and {{Wiki|cultural}} gatherings, where {{Wiki|priests}} and {{Wiki|community}} members together rehearsed and transmitted [[language]], skills, and {{Wiki|cultural}} {{Wiki|behavior}} to the next generation. Functional differentiation, specialization, and later fragmentation of the communities with migration, out-marriage, [[conversion]], and |

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | continued efforts of {{Wiki|cultural}} assimilation made the [[religious]] {{Wiki|institutions}} less important for the {{Wiki|diaspora}} group. [[Traditional]] [[temple]] functions have been taken over by other domains, and [[education]], [[sports]], {{Wiki|welfare}}, [[health]] [[care]], and [[death]] [[care]] are no longer part of [[religious]] [[life]]. As in {{Wiki|Canada}}, | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | “{{Wiki|evidence}} for a pattern of {{Wiki|ethnic}} rediscovery is not to be found among third generation {{Wiki|Japanese}}” (Mullins, 1988: 231). This seems to follow a general pattern: Asian-Americans constitute the section of the [[American]] | ||

| − | + | that is most likely to have no [[religious]] [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]], a tendency that has increased since the | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

1990s (Kosmin and Keysar, 2009: 15). This is similar to the {{Wiki|reasoning}} of an adherent of | 1990s (Kosmin and Keysar, 2009: 15). This is similar to the {{Wiki|reasoning}} of an adherent of | ||

one of the Paia [[temples]]: “In those days, [[Buddhism]] was more colorful. Now it has become more flat.” | one of the Paia [[temples]]: “In those days, [[Buddhism]] was more colorful. Now it has become more flat.” | ||

| Line 138: | Line 364: | ||

b. Institutional ethnification strategies | b. Institutional ethnification strategies | ||

| − | Contrary to the developments of de-ethnification and secularization, there are also developments of ethnification strategies. As is the case with the islands, the RZM and Mantokuji [[temples]] are independent, but at the same [[time]] affiliated to their {{Wiki|Japanese}} mother {{Wiki|institutions}}. The latter still insist that all [[monks]] and students in training should study and train in [[Japan]]; that missionary ministers should be sent from [[Japan]] (not to convert non-Buddhists, but to serve the [[existing]] Japanese-American community); that etiquette ought to be observed in a proper {{Wiki|Japanese}} way. This has led to controversies which in turn have made it obvious that conflicts of interest are grounded in cultural differences, and that [[Japan]] and Hawaii are further apart than geography may suggest.24 | + | |

| − | In general, [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] “are solidly | + | Contrary to the developments of de-ethnification and secularization, there are also developments of ethnification strategies. As is the case with the islands, the RZM and Mantokuji [[temples]] are {{Wiki|independent}}, but at the same [[time]] affiliated to their {{Wiki|Japanese}} mother {{Wiki|institutions}}. The [[latter]] still insist that all |

| + | |||

| + | [[monks]] and students in {{Wiki|training}} should study and train in [[Japan]]; that {{Wiki|missionary}} ministers should be sent from [[Japan]] (not to convert non-Buddhists, but to serve the [[existing]] Japanese-American {{Wiki|community}}); that {{Wiki|etiquette}} ought to be observed in a proper {{Wiki|Japanese}} way. This has led to controversies which in turn have made it | ||

| + | |||

| + | obvious that conflicts of [[interest]] are grounded in {{Wiki|cultural}} differences, and that [[Japan]] and [[Hawaii]] are further apart than {{Wiki|geography}} may suggest.24 | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In general, [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] “are solidly {{Wiki|sectarian}}” ([[Tanabe]], 2005: 96) and have “locked them into a [[religious]] {{Wiki|culture}} that is westernized on the surface but remains unassimilated at its core” (ibid., 78).25 Also a more {{Wiki|unconsciously}} “bottom-up” {{Wiki|culture}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 24 According to a survey conducted by the now vanished [[Honpa Hongwanji]] [[Mission]] of [[Hawaii]], only 3 percent of the responding members wanted things done in the “{{Wiki|Japanese}} way.” | ||

| + | 25 “No trespassing,” “keep out,” “beware of {{Wiki|dog}},” and a large fence surrounding the building in a | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Honolulu-based [[temple]] with a [[priest]] who did not {{Wiki|communicate}} in English was one symptomatic, albeit rather extreme example of a separation and isolation strategy. The same top-down ethnification strategy is seen | |

| − | Honolulu-based [[temple]] with a priest who did not {{Wiki|communicate}} in English was one symptomatic, albeit rather extreme example of a separation and isolation strategy. The same top-down ethnification strategy is seen among other Asian [[religious]] groups in Hawaii. After a {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[monk]] in Honolulu had attempted to spiritualize and thereby internationalize [[Buddhism]], other more conservative [[monks]] returned to the same isolationist culture religiosity, which has | + | |

| + | among other {{Wiki|Asian}} [[religious]] groups in [[Hawaii]]. After a {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[monk]] in [[Honolulu]] had attempted to spiritualize and thereby internationalize [[Buddhism]], other more conservative [[monks]] returned to the same isolationist {{Wiki|culture}} religiosity, which has | ||

| − | prevails in the two {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[temples]]. Throughout the years, the current priests have made attempts to open the [[temples]] to new adherents, and several interviews with different members revealed a generally positive [[attitude]] toward welcoming more non-Japanese into the [[temples]]. But both insiders and outsiders (potential newcomers) complained that the [[temple]] communities are more ethnically bonding than trans-ethnically bridging. As one of the core members said, “we have to be more open and global to survive.” The priest at the RZM, who promotes such initiatives, points to the overall dilemma when referring to his [[concern]] for the | + | prevails in the two {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[temples]]. Throughout the years, the current {{Wiki|priests}} have made attempts to open the [[temples]] to new {{Wiki|adherents}}, and several interviews with different members revealed a generally |

| + | |||

| + | positive [[attitude]] toward welcoming more non-Japanese into the [[temples]]. But both insiders and outsiders (potential newcomers) complained that the [[temple]] communities are more ethnically bonding than trans- | ||

| + | |||

| + | ethnically bridging. As one of the core members said, “we have to be more open and global to survive.” The [[priest]] at the RZM, who promotes such initiatives, points to the overall {{Wiki|dilemma}} when referring to his [[concern]] for the “{{Wiki|culture}} [[Buddhists]]”: “I cannot ignore the old [[people]].” | ||

| + | |||

[[File:Buddha zg70.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Buddha zg70.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

c. Individualization | c. Individualization | ||

| − | Although it is problematic to establish [[causal]] links between subjectivization and secularization (Heelas and Woodhead, 2005: 127), the increasing [[sense]] of individualization constitutes one important sub-factor that has clearly challenged communal [[religion]] and {{Wiki|ethnic}} identity. With intensified individualization, {{Wiki|social}} capital declines, and Putnam’s (2000) “bowling alone” {{Wiki|metaphor}} can thus also be used to describe the developments in [[religious]] communities. Third and fourth-generation children were successfully Americanized and individualized, at the expense of their | + | Although it is problematic to establish [[causal]] links between subjectivization and secularization (Heelas and Woodhead, 2005: 127), the increasing [[sense]] of individualization constitutes one important sub-factor that has clearly challenged communal [[religion]] and {{Wiki|ethnic}} [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]]. With intensified individualization, |

| − | 128). Some converted to {{Wiki|{{Wiki|Christianity}}}}, perhaps strategically adopting a “truly | + | |

| − | [[religion]]. Others simply gave up on [[religion]] altogether, ignoring the demands of intergenerational [[transmission]]. [[Religious]] involvement takes [[time]] (“If you take responsibility, you do it for [[life]],” as one informant said) and several respondents voiced their (and especially their children’s) reluctance to invest a part of their [[life]] in this. One informant phrased the challenge that [[traditional]] [[religious]] {{Wiki|institutions}} had to face in the 1960s, referring to increasing consumerism: “when the nearby shopping center was built, Sunday became the day of shopping.” And in the words of the RZM minister, “the beach is their church.” Interviews with third and fourth-generation descendants of the {{Wiki|Japanese}} immigrants clearly showed that identity construction with reference to an {{Wiki|ethnic}} and [[religious]] community no longer has the same {{Wiki|persuasive}} [[power]]. Non-religiosity and a hybrid [[sense]] of identity are justified by the “individualization project,” though often nostalgically mourned by older {{Wiki|Japanese}} Americans who try to find | + | {{Wiki|social}} capital declines, and Putnam’s (2000) “bowling alone” {{Wiki|metaphor}} can thus also be used to describe the developments in [[religious]] communities. Third and fourth-generation children were successfully Americanized and individualized, at the expense of their {{Wiki|ancestors}}’ {{Wiki|cultural}} baggage. Especially the neglect of |

| + | |||

| + | the {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[language]] and [[traditions]] has been a key factor for {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]] “committing slow [[suicide]]” ([[Tanabe]], 2005: 77). Several older [[people]] underlined this fact in the interviews I conducted, and as one informant said, “We told them to do their [[own]] thing. But did we go too far?” Individualization | ||

| + | |||

| + | also means having the freedom to choose. Many chose not to maintain {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] and commit to the [[religion]] of their {{Wiki|ancestors}}, which is typically “[[manifested]] through the [[family]] rather than the {{Wiki|individual}}” (Kashima, 2008: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 128). Some converted to {{Wiki|{{Wiki|Christianity}}}}, perhaps strategically adopting a “truly [[American]]” | ||

| + | [[religion]]. Others simply gave up on [[religion]] altogether, ignoring the demands of intergenerational [[transmission]]. [[Religious]] involvement takes [[time]] (“If you take {{Wiki|responsibility}}, you do it for [[life]],” as | ||

| + | |||

| + | one informant said) and several respondents voiced their (and especially their children’s) reluctance to invest a part of their [[life]] in this. One informant phrased the challenge that [[traditional]] [[religious]] {{Wiki|institutions}} had to face in the 1960s, referring to increasing consumerism: “when the nearby shopping center | ||

| + | |||

| + | was built, [[Sunday]] became the day of shopping.” And in the words of the RZM [[minister]], “the beach is their {{Wiki|church}}.” Interviews with third and fourth-generation descendants of the {{Wiki|Japanese}} immigrants clearly showed that [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] construction with reference to an {{Wiki|ethnic}} and [[religious]] {{Wiki|community}} no longer has the same | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|persuasive}} [[power]]. Non-religiosity and a hybrid [[sense]] of [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] are justified by the “individualization project,” though often nostalgically mourned by older {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]] who try to find | ||

| − | generally characterized organized [[Chinese Buddhism]] in Hawaii. [[Adaptation]] strategies are naturally also differentiated among the Japanese-American [[Buddhist]] [[temples]]. At the other end of the spectrum, a [[Shingon]] [[temple]] in Honolulu that has become independent of its {{Wiki|Japanese}} mother organization has been successful in adapting to its surroundings and getting more (also young) committed members, primarily due to a progressive priest. | + | a [[balance]] in keeping [[tradition]] alive in a {{Wiki|society}} that honors [[individuality]] and the free market. |

| + | |||

| + | [[generally characterized]] organized [[Chinese Buddhism]] in [[Hawaii]]. [[Adaptation]] strategies are naturally also differentiated among the Japanese-American [[Buddhist]] [[temples]]. At the other end of the spectrum, a [[Shingon]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[temple]] in [[Honolulu]] that has become {{Wiki|independent}} of its {{Wiki|Japanese}} mother [[organization]] has been successful in adapting to its surroundings and getting more (also young) committed members, primarily due to a progressive [[priest]]. | ||

| Line 163: | Line 425: | ||

d. [[Buddhism]] at the market place | d. [[Buddhism]] at the market place | ||

| − | |||

| − | Hawaii ideals of a harmonious | + | |

| + | Market and [[rational]] choice {{Wiki|theory}} of [[religion]] would argue that such internal factors alone cannot explain one-way {{Wiki|secular}} {{Wiki|tendencies}}. From a macro {{Wiki|perspective}}, external factors also point to {{Wiki|tendencies}} of both increase and {{Wiki|decrease}} of [[religion]], of both spiritualization and secularization. These changes and {{Wiki|tendencies}} do not directly affect the Japanese-American [[Buddhists]], but they do indicate general changes in [[Buddhism]] and in [[religious]] transformations in a late {{Wiki|modern}} context. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Hawaii]] ideals of a harmonious “[[rainbow]] of races” and a pluralistic “[[rainbow]] of [[religions]]” have, to some extent, become a [[reality]]. On the {{Wiki|individual}} level, many members from the two [[temples]] participate in [[religious]] [[activities]] across [[religious]] and institutional divides. Many are “hybrid [[religious]],” members of | ||

| + | |||

| + | both Mantokuji and local {{Wiki|Christian}} churches; others adjust to the religiosity of their spouse by pragmatically attending services in both [[religions]]. But a market parameter also reveals a competitive diversity. The evangelical churches in [[Hawaii]] (one is based in neighboring Kahului) as well as the trans-ethnically oriented | ||

| + | |||

| + | S6ka Gakkai (SGI)26 have been successful in gaining and engaging new members with the same kind of “all inclusive” [[activities]] and [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] commitment that the [[traditional]] and {{Wiki|ethnic}} churches used to resort to. This seems to suggest the plausibility of a market-oriented “strictness {{Wiki|hypothesis}},” claiming that | ||

| + | |||

| + | strict and exclusivist [[religions]], while also [[being]] inclusivist regarding ethnicity and race, are better survivors in the [[religious]] market as they are better at keeping members and attracting new {{Wiki|adherents}} from other, less bounded, [[religious]] groups (Kelley, 1974; Iannaccone, 1994). On the other hand, the mono-ethnic and | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[tradition]] based “{{Wiki|culture}} religiosity,” where personal [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] and continuity with the {{Wiki|past}} is kept, “even after participation in [[ritual]] and [[belief]] has lapsed” (Demerath, 2000: 127), seems to have been on the {{Wiki|decrease}}. In | ||

| + | |||

| + | recent decades, [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Christian}} churches with a historical [[connection]] to {{Wiki|Japanese}} immigrants and later descendants in [[Hawaii]] have [[experienced]] a {{Wiki|decrease}} in membership numbers.27 The same is true for [[Buddhist]] churches, whose | ||

| + | |||

[[File:Daibutsu todaiji.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Daibutsu todaiji.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | 26 According to the SGI-USA [[Peace]] & Community Relations, there were 8,100 members in all of Hawaii in 2010 (7,780 in 2000). Most members reside in Honolulu, while Maui has 450 members. A local representative in Honolulu estimated that 60 percent hereof and of the 300 members who participate in weekend services are {{Wiki|Japanese}} Americans. By combining concrete and accessible {{Wiki|theology}} and practice for the modern {{Wiki|individual}} with modern techniques and international/global culture, SGI sees itself as counterbalancing [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[temple]] [[Buddhism]]. The “strictness” of SGI has been softened somewhat throughout the years, as [[manifested]] by the change from the period of evangelism in the 1960s to the period of dialogue in the 1990s. American values like individualism, capitalism, and self-expression have been accommodated. Because the communal centers are more religiously and culturally ambitious alternatives to the [[traditional]] [[temples]], SGI in the USA has been truly multiethnic, and in Hawaii “S6ka Gakkai, with its strategy of inclusive pluralism, may be the exception to this exclusive pattern” (Tanabe, 2005: 97). | + | 26 According to the SGI-USA [[Peace]] & {{Wiki|Community}} Relations, there were 8,100 members in all of [[Hawaii]] in 2010 (7,780 in 2000). Most members reside in [[Honolulu]], while [[Maui]] has 450 members. A local representative in [[Honolulu]] |

| − | 27 Interviews with several church ministers in both Maui and the Honolulu area justify such | + | |

| − | generalized claims of membership decreases. A survey from Honolulu of 1983 states: “What has happened is that there has been a drastic decline in the number of young {{Wiki|Japanese}} Americans attracted to {{Wiki|{{Wiki|Christianity}}}}. But the [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] are not attracting these young [[people]] to | + | estimated that 60 percent hereof and of the 300 members who participate in weekend services are {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]]. By [[combining]] concrete and accessible {{Wiki|theology}} and practice for the {{Wiki|modern}} {{Wiki|individual}} with {{Wiki|modern}} [[techniques]] and international/global {{Wiki|culture}}, [[SGI]] sees itself as counterbalancing [[traditional]] |

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[temple]] [[Buddhism]]. The “strictness” of [[SGI]] has been softened somewhat throughout the years, as [[manifested]] by the change from the period of evangelism in the 1960s to the period of {{Wiki|dialogue}} in the 1990s. [[American]] values like {{Wiki|individualism}}, [[capitalism]], and self-expression have been accommodated. Because the | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | communal centers are more religiously and culturally ambitious alternatives to the [[traditional]] [[temples]], [[SGI]] in the {{Wiki|USA}} has been truly multiethnic, and in [[Hawaii]] “S6ka Gakkai, with its strategy of inclusive [[pluralism]], may be the exception to this exclusive pattern” ([[Tanabe]], 2005: 97). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 27 Interviews with several {{Wiki|church}} ministers in both [[Maui]] and the [[Honolulu]] area justify such | ||

| + | generalized claims of membership {{Wiki|decreases}}. A survey from [[Honolulu]] of 1983 states: “What has happened is that there has been a drastic {{Wiki|decline}} in the number of young {{Wiki|Japanese}} [[Americans]] attracted to {{Wiki|{{Wiki|Christianity}}}}. But the [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] are not attracting these young [[people]] to | ||

| − | {{Wiki|theological}} and institutional “softness” appears to be a handicap in this connection (Tamney, 2008); it may also be one of the explanations for the decrease in immigrant “[[Buddhism]] of yellow | + | {{Wiki|theological}} and institutional “softness” appears to be a handicap in this [[connection]] (Tamney, 2008); it may also be one of the explanations for the {{Wiki|decrease}} in immigrant “[[Buddhism]] of [[yellow]] {{Wiki|color}}” in {{Wiki|Brazil}} (Ursaki, 2008: 39), in the {{Wiki|USA}} (Bloom, 1998; Tanaka, 1999), and in {{Wiki|Canada}} (Beyer, 2010a).28 |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The holistic market in Paia and the surrounding area is a typical example of the [[spirituality]] that has been available for the last 20 years. {{Wiki|Individuals}}, groups, and studios come and go, [[offering]] different kinds of [[spiritual]] services and practices such as [[yoga]], [[meditation]], [[healing]], tai [[chi]], qi gong, kinesiology, tarot, reiki, herbal [[medicine]], intuitive reading, [[tantra]], and shamanistic journeys. The organic shop [[Mana]] [[Foods]], catering to | + | Another general trend of which the long-term {{Wiki|decrease}} of immigrant [[Buddhism]] can be said to be a part is what Heelas and Woodhead call the “[[spiritual]] {{Wiki|revolution}}” (2005), in which [[traditional]] churches and “other-worldly” [[religions]] lose ground to individualized and “this-worldly” sacralization of the [[self]], invoking “the |

| + | |||

| + | [[sacred]] in the [[cultivation]] of unique subjective-life” (ibid.: 5). As such, the “{{Wiki|holistic}} {{Wiki|environment}} prioritizes the individual’s right of private [[judgment]], just as {{Wiki|epistemological}} {{Wiki|individualism}} privileges personal choice and [[experience]] over the [[wisdom]] of [[traditions]] and [[gurus]]” (Warner, | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | 2010: 157). Euro-American [[Buddhist]] converts, represented in Paia by the [[Maui Zendo]] and the [[Tibetan]] [[Dharma]] Center,29 are in a [[sense]] catering for a [[spiritually]] oriented group, typically Euro-Americans. Most members of both the [[Zen]] and the [[Tibetan]] groups have been part of a {{Wiki|stable}} {{Wiki|community}} for many years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although the convert groups have not been affected as much as the Japanese-American [[Buddhist]] groups, they have still [[experienced]] a {{Wiki|decline}} in membership, [[caused]] by general secularization {{Wiki|tendencies}}. In the words of a resident of the [[Dharma]] [[Center]], “We are in {{Wiki|decline}} because [[Buddhism]] is declining.” Neither “strict” | ||

| + | |||

| + | nor institution-negating enough, the Euro-American groups are still {{Wiki|distinct}} from typical Japanese-American [[Buddhism]]. They have, however, in many ways become {{Wiki|mainstream}}, functioning as “parallel congregations” (Numrich, 2003) within a [[traditional]] Sangha-oriented version of [[Buddhism]]. | ||

| + | |||