Difference between revisions of "Gorampa"

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

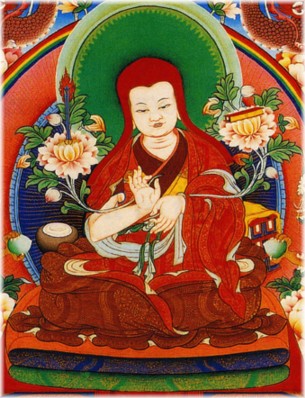

| − | [[Gorampa Sonam Senge]] ([[Go rams pa bSod nams Seng ge]], 1429–89) is one of the most widely-studied philosophers in the [[Sakya]] ([[sa skya]]) school of [[Tibetan Buddhism]]. A fierce critic of Tsongkhapa, the founder of what later came to be known as the Gelug (dge lugs) school, his works were so controversial that they were suppressed by Gelug leaders shortly after they were composed. | + | [[Gorampa Sonam Senge]] ([[Go rams pa bSod nams Seng ge]], 1429–89) is one of the most widely-studied [[philosophers]] in the [[Sakya]] ([[sa skya]]) school of [[Tibetan Buddhism]]. A fierce critic of [[Tsongkhapa]], the founder of what later came to be known as the [[Gelug]] ([[dge lugs]]) school, his works were so controversial that they were suppressed by [[Gelug]] leaders shortly after they were composed. |

| − | [[Gorampa’s]] texts remained hidden until the early 20th century, when the monk Jamgyal Rinpoche received permission from the thirteenth Dalai Lama to collect Gorampa’s extant texts and have them reprinted in Derge. Today, Gorampa’s philosophy is studied widely in monastic colleges, not only in those affiliated with his own Sakya tradition, but also in institutions affiliated with the Kagyu ([[bka' brgyud]]) and Nyingma ([[rnying ma]]) schools. | + | [[Gorampa’s]] texts remained hidden until the early 20th century, when the [[monk]] Jamgyal [[Rinpoche]] received permission from the [[thirteenth Dalai Lama]] to collect [[Gorampa’s]] extant texts and have them reprinted in [[Derge]]. Today, [[Gorampa’s]] [[philosophy]] is studied widely in [[monastic]] {{Wiki|colleges}}, not only in those affiliated with his [[own]] [[Sakya tradition]], but also in {{Wiki|institutions}} affiliated with the [[Kagyu]] ([[bka' brgyud]]) and [[Nyingma]] ([[rnying ma]]) schools. |

| − | [[Gorampa]], like most Tibetan Buddhist philosophers, considers himself a follower of the Madhyamaka (Middle Way) school developed by the Indian philosopher Nāgārjuna in the second century, CE. | + | [[Gorampa]], like most [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[philosophers]], considers himself a follower of the [[Madhyamaka]] ([[Middle Way]]) school developed by the [[Indian philosopher]] [[Nāgārjuna]] in the second century, CE. |

| − | His views with respect to particular issues within Madhyamaka, however, differ significantly from the views of scholars belonging to other sects of Tibetan Buddhism (e.g., Tsongkhapa and Dolpopa), and at times, his views even differ from those of other Sakya scholars (most notably Shakya Chokden). | + | His [[views]] with [[respect]] to particular issues within [[Madhyamaka]], however, differ significantly from the [[views]] of [[scholars]] belonging to other sects of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] (e.g., [[Tsongkhapa]] and [[Dolpopa]]), and at times, his [[views]] even differ from those of other [[Sakya]] [[scholars]] (most notably [[Shakya Chokden]]). |

| − | Gorampa’s particular brand of Madhyamaka philosophy is defined by his understanding of the relationship between the two truths, the use of negation, the role of logic, and proper methods of philosophical argumentation. | + | [[Gorampa’s]] particular brand of [[Madhyamaka philosophy]] is defined by his [[understanding]] of the relationship between the [[two truths]], the use of {{Wiki|negation}}, the role of [[logic]], and proper [[methods]] of [[philosophical]] {{Wiki|argumentation}}. |

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | 1. Life and Works | + | 1. [[Life]] and Works |

| − | 2. Gorampa’s Madhyamaka | + | 2. [[Gorampa’s]] [[Madhyamaka]] |

| − | 2.1 The Two Truths | + | 2.1 The [[Two Truths]] |

| − | 2.2 Negation | + | 2.2 {{Wiki|Negation}} |

| − | 2.3 The Role of Logic | + | 2.3 The Role of [[Logic]] |

| − | 2.4 Methods of Argumentation | + | 2.4 [[Methods]] of Argumentation |

| − | 3. Influence on Other Philosophers | + | 3. Influence on Other [[Philosophers]] |

| − | Bibliography | + | [[Bibliography]] |

| − | Academic Tools | + | {{Wiki|Academic}} Tools |

| − | Other Internet Resources | + | Other [[Internet]] Resources |

Related Entries | Related Entries | ||

</poem> | </poem> | ||

| Line 71: | Line 71: | ||

| − | 1. Life and Works | + | 1. [[Life]] and Works |

| − | Gorampa was born in 1429 in eastern Tibet. At age nineteen, he traveled to central Tibet to pursue monastic studies. He briefly attended Nalendra monastery, one of the prominent Sakya monastic institutions in Tibet, where he studied Madhyamaka texts with the scholar Rongton (rong ston). | + | [[Gorampa]] was born in 1429 in [[eastern Tibet]]. At age nineteen, he traveled to [[central Tibet]] to pursue [[monastic]] studies. He briefly attended [[Nalendra monastery]], one of the prominent [[Sakya]] [[monastic institutions]] [[in Tibet]], where he studied [[Madhyamaka]] texts with the [[scholar]] [[Rongton]] ([[rong]] ston). |

| − | Rongton passed away the following summer, and Gorampa began to travel throughout central Tibet, studying with a number of other teachers. In addition to becoming a skilled philosopher, Gorampa mastered a variety of Tantric practices, including the Lamdre (lam ‘bras), the defining practice of the Sakya School. | + | [[Rongton]] passed away the following summer, and [[Gorampa]] began to travel throughout [[central Tibet]], studying with a number of other [[teachers]]. In addition to becoming a [[skilled]] [[philosopher]], [[Gorampa]] mastered a variety of [[Tantric practices]], [[including]] the [[Lamdre]] ([[lam ‘bras]]), the defining practice of the [[Sakya School]]. |

| − | After completing his studies, Gorampa became a teacher, and in 1473 he founded Thubten Namgyal Ling Monastery, developing a curriculum that emphasized both rigorous philosophical education and thorough training in meditative practices. Gorampa later spent four years as the sixth abbot of Ewam Choden, the primary institution of the Ngor subsect of the Sakya school. He died in 1489. | + | After completing his studies, [[Gorampa]] became a [[teacher]], and in 1473 he founded Thubten [[Namgyal Ling]] [[Monastery]], developing a {{Wiki|curriculum}} that emphasized both rigorous [[philosophical]] [[education]] and thorough {{Wiki|training}} in [[meditative practices]]. [[Gorampa]] later spent four years as the sixth [[abbot]] of Ewam Choden, the primary institution of the [[Ngor]] subsect of the [[Sakya school]]. He [[died]] in 1489. |

| − | Gorampa lived during a period of political instability in Tibet. From 1244 until 1354, the Sakya sect had held political control over Tibet, and was backed by the support of the Mongol army. Eventually the Mongolian court’s interest in Tibet weakened, and the Pagmodruk sect of Tibetan Buddhism ousted the Sakyapas from power in a violent confrontation. | + | [[Gorampa]] lived during a period of {{Wiki|political}} instability [[in Tibet]]. From 1244 until 1354, the [[Sakya sect]] had held {{Wiki|political}} control over [[Tibet]], and was backed by the support of the {{Wiki|Mongol}} {{Wiki|army}}. Eventually the {{Wiki|Mongolian}} court’s [[interest]] [[in Tibet]] weakened, and the Pagmodruk [[sect]] of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] ousted the [[Sakyapas]] from power in a [[violent]] confrontation. |

| − | The Pagmodrukpas ruled over Tibet for 130 years, but during the latter half of Gorampa’s life, they fell from power, resulting in a number of groups fiercely competing for religious and political dominance. | + | The Pagmodrukpas ruled over [[Tibet]] for 130 years, but during the [[latter]] half of [[Gorampa’s]] [[life]], they fell from power, resulting in a number of groups fiercely competing for [[religious]] and {{Wiki|political}} dominance. |

| − | Gorampa composed his philosophical texts, therefore, at a time in which the Sakya sect was struggling to re-assert its dominance. Although verifiable information about the political motivations of the Sakyapas remains elusive, the unstable political situation in Tibet could have at least partially accounted for the overtly polemical nature of some of Gorampa’s Madhyamaka texts. | + | [[Gorampa]] composed his [[philosophical]] texts, therefore, at a time in which the [[Sakya sect]] was struggling to re-assert its dominance. Although verifiable [[information]] about the {{Wiki|political}} motivations of the [[Sakyapas]] remains elusive, the unstable {{Wiki|political}} situation [[in Tibet]] could have at least partially accounted for the overtly polemical [[nature]] of some of [[Gorampa’s]] [[Madhyamaka]] texts. |

| − | When the Gelugpas eventually ascended to political power in the sixteenth century, the fifth Dalai Lama ordered that Gorampa’s texts, which were so critical of Tsongkhapa, be destroyed or otherwise removed from monastic institutions. However, many of Gorampa’s texts continued to be studied in eastern Tibet, where the central government was unable to exert a strong influence. | + | When the [[Gelugpas]] eventually ascended to {{Wiki|political}} power in the sixteenth century, the [[fifth Dalai Lama]] ordered that [[Gorampa’s]] texts, which were so critical of [[Tsongkhapa]], be destroyed or otherwise removed from [[monastic institutions]]. However, many of [[Gorampa’s]] texts continued to be studied in [[eastern Tibet]], where the central government was unable to exert a strong influence. |

| − | When work began on the republication of Gorampa’s writings in 1905, thirteen volumes of texts were recovered from monasteries throughout Tibet. In addition to his works on Madhyamaka philosophy, Gorampa composed a number of treatises on Abhidharma, several commentaries on the Indian text the Abhisamayālaṅkāra, and various practice texts based on Tantra. | + | When work began on the republication of [[Gorampa’s]] writings in 1905, thirteen volumes of texts were recovered from [[monasteries]] throughout [[Tibet]]. In addition to his works on [[Madhyamaka philosophy]], [[Gorampa]] composed a number of treatises on [[Abhidharma]], several commentaries on the [[Indian]] text the [[Abhisamayālaṅkāra]], and various practice texts based on [[Tantra]]. |

| − | Gorampa’s major Madhyamaka texts, which will form the basis for the rest of this article, comprise only two of these thirteen volumes. His three major Madhyamaka texts are: | + | [[Gorampa’s]] major [[Madhyamaka]] texts, which will [[form]] the basis for the rest of this article, comprise only two of these thirteen volumes. His three major [[Madhyamaka]] texts are: |

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | Freedom from Extremes (lta ba’i shan ‘byed), a polemical text distinguishing Gorampa’s own view from those of Tsongkhapa (Tsong kha pa bLo bzang Grags pa, 1357–1419) and Dolpopa (Dol po pa Shes rab rGyal mtshan, 1292–1361); | + | Freedom from Extremes (lta ba’i [[shan ‘byed]]), a polemical text distinguishing [[Gorampa’s]] [[own]] view from those of [[Tsongkhapa]] ([[Tsong kha pa]] bLo bzang [[Grags pa]], 1357–1419) and [[Dolpopa]] ([[Dol po pa Shes rab rGyal mtshan]], 1292–1361); |

| − | Elucidating the View (lta ba ngan sel), a commentary on the Indian scholar Candrakīrti’s Madhyamakāvatāra; | + | Elucidating the View ([[lta ba]] [[ngan]] sel), a commentary on the [[Indian scholar]] [[Candrakīrti’s]] [[Madhyamakāvatāra]]; |

| − | The General Meaning of Madhyamaka (dbu ma’i spyi don), an encyclopedic text outlining Gorampa’s views on the major points of Madhyamaka, as well as the views of a number of Indian and Tibetan scholars with whom he both agrees and disagrees. | + | The General Meaning of [[Madhyamaka]] (dbu ma’i [[spyi]] don), an [[encyclopedic]] text outlining [[Gorampa’s]] [[views]] on the major points of [[Madhyamaka]], as well as the [[views]] of a number of [[Indian]] and [[Tibetan scholars]] with whom he both agrees and disagrees. |

| Line 117: | Line 117: | ||

</poem> | </poem> | ||

| − | Although there are some subtle differences in the presentation of Gorampa’s philosophy in each of these three texts, his explanation of Madhyamaka is relatively consistent throughout his writings. The remainder of this article will provide a general sketch of Gorampa’s Madhyamaka views as they are presented in all three of these texts. | + | Although there are some {{Wiki|subtle}} differences in the presentation of [[Gorampa’s]] [[philosophy]] in each of these three texts, his explanation of [[Madhyamaka]] is relatively consistent throughout his writings. The remainder of this article will provide a general sketch of [[Gorampa’s]] [[Madhyamaka views]] as they are presented in all three of these texts. |

| − | 2. Gorampa’s Madhyamaka | + | 2. [[Gorampa’s]] [[Madhyamaka]] |

| − | Because Gorampa was educated in the Tibetan monastic system, he affiliates himself with the Madhyamaka school of Buddhist thought. All Tibetan Buddhist philosophers cite Nāgārjuna’s texts as authoritative, and disagreements among different scholars in Tibetan Buddhism primarily concern the correct ways to interpret the works of Nāgārjuna and his commentators. | + | Because [[Gorampa]] was educated in the [[Tibetan]] [[monastic]] system, he affiliates himself with the [[Madhyamaka school]] of [[Buddhist]] [[thought]]. All [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[philosophers]] cite [[Nāgārjuna’s]] texts as authoritative, and disagreements among different [[scholars]] in [[Tibetan Buddhism]] primarily [[concern]] the correct ways to interpret the works of [[Nāgārjuna]] and his commentators. |

| − | As such, the basis of Gorampa’s views are relatively non-controversial in the context of Tibetan Madhyamaka. | + | As such, the basis of [[Gorampa’s]] [[views]] are relatively non-controversial in the context of [[Tibetan Madhyamaka]]. |

| − | His philosophy is based on Nāgārjuna’s concepts of emptiness and the two truths, and, like all Buddhists, Gorampa agrees that the elimination of ignorance will eliminate suffering and lead to enlightenment. What distinguishes Gorampa’s Madhyamaka from that of other Tibetan scholars is more subtle. | + | His [[philosophy]] is based on [[Nāgārjuna’s]] [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] of [[emptiness]] and the [[two truths]], and, like all [[Buddhists]], [[Gorampa]] agrees that the elimination of [[ignorance]] will eliminate [[suffering]] and lead to [[enlightenment]]. What distinguishes [[Gorampa’s]] [[Madhyamaka]] from that of other [[Tibetan scholars]] is more {{Wiki|subtle}}. |

| − | His understanding of the nature of emptiness, ignorance, and the two truths, as well as his articulation of the proper methods for realizing emptiness and attaining enlightenment, are what originally set Gorampa apart from other scholars, and what ultimately led to the censoring of his texts in Tibet. | + | His [[understanding]] of the [[nature of emptiness]], [[ignorance]], and the [[two truths]], as well as his articulation of the proper [[methods]] for [[realizing]] [[emptiness]] and [[attaining enlightenment]], are what originally set [[Gorampa]] apart from other [[scholars]], and what ultimately led to the censoring of his texts [[in Tibet]]. |

| − | The scholar with whom Gorampa most vehemently disagrees in his Madhyamaka texts is Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), the scholar who founded what later came to be known as the Gelug sect. | + | The [[scholar]] with whom [[Gorampa]] most vehemently disagrees in his [[Madhyamaka]] texts is [[Tsongkhapa]] (1357–1419), the [[scholar]] who founded what later came to be known as the [[Gelug sect]]. |

| − | Before establishing his own monastery and composing his own philosophical commentaries, Tsongkhapa received a significant portion of his training from Sakya teachers. | + | Before establishing his [[own]] [[monastery]] and composing his [[own]] [[philosophical]] commentaries, [[Tsongkhapa]] received a significant portion of his {{Wiki|training}} from [[Sakya teachers]]. |

| − | It is possible, therefore, that Gorampa made such overtly critical remarks against Tsongkhapa’s views because the former saw the latter as misconstruing the Sakya philosophical tradition. | + | It is possible, therefore, that [[Gorampa]] made such overtly critical remarks against [[Tsongkhapa’s]] [[views]] because the former saw the [[latter]] as misconstruing the [[Sakya]] [[philosophical]] [[tradition]]. |

| − | Several works have been published in English that focus explicitly on the debates between Gorampa and Tsongkhapa (see Cabezon & Dargay 2007, Thakchoe 2007). While his philosophical treatises were undoubtedly composed partly in response to Tsongkhapa’s views, the remainder of this section will concern itself with Gorampa’s own views, only drawing comparisons to Tsongkhapa when Gorampa has specifically constructed his arguments in such a way. | + | Several works have been published in English that focus explicitly on the [[debates]] between [[Gorampa]] and [[Tsongkhapa]] (see [[Cabezon]] & Dargay 2007, Thakchoe 2007). While his [[philosophical]] treatises were undoubtedly composed partly in response to [[Tsongkhapa’s]] [[views]], the remainder of this section will [[concern]] itself with [[Gorampa’s]] [[own]] [[views]], only drawing comparisons to [[Tsongkhapa]] when [[Gorampa]] has specifically [[constructed]] his arguments in such a way. |

| − | With this in mind, there are four defining characteristics of Gorampa’s philosophy that set him apart from other Tibetan philosophers. They are his understandings of: | + | With this in [[mind]], there are four [[defining characteristics]] of [[Gorampa’s]] [[philosophy]] that set him apart from other [[Tibetan]] [[philosophers]]. They are his understandings of: |

| − | (1) the two truths; (2) negation and the tetralemma; (3) the role of logic and reasoning; and (4) proper methods of argumentation on the path to Buddhist enlightenment. | + | (1) the [[two truths]]; (2) {{Wiki|negation}} and the [[tetralemma]]; (3) the role of [[logic and reasoning]]; and (4) proper [[methods]] of {{Wiki|argumentation}} on the [[path]] to [[Buddhist enlightenment]]. |

| − | 2.1 The Two Truths | + | 2.1 The [[Two Truths]] |

| − | The theory of the two truths is fundamental to all Madhyamaka philosophy. Reality is understood in terms of the conventional truth, which corresponds to the perspectives of ordinary beings, and the ultimate truth, which can only be perceived by enlightened beings. | + | The {{Wiki|theory}} of the [[two truths]] is fundamental to all [[Madhyamaka philosophy]]. [[Reality]] is understood in terms of the [[conventional truth]], which corresponds to the perspectives of [[ordinary beings]], and [[the ultimate truth]], which can only be [[perceived]] by [[enlightened beings]]. |

| − | While Mādhyamikas tend to disagree about the nature of and relationship between the conventional and ultimate truths, the final goal of Madhyamaka philosophy involves arriving at a direct realization of the ultimate truth. | + | While [[Mādhyamikas]] tend to disagree about the [[nature]] of and relationship between the [[conventional and ultimate truths]], the final goal of [[Madhyamaka philosophy]] involves arriving at a [[direct realization]] of [[the ultimate truth]]. |

| − | Gorampa argues that the two truths are divided based on the perspective of an apprehending subject (yul can), rather than being divided on the basis of an apprehended object (yul). | + | [[Gorampa]] argues that the [[two truths]] are divided based on the {{Wiki|perspective}} of an apprehending [[subject]] ([[yul can]]), rather than being divided on the basis of an [[apprehended object]] (yul). |

| − | The way in which one engages with the world determines whether one perceives things conventionally or ultimately. The conventional truth involves concepts, logic, and reasoning, while the ultimate truth is outside of the realm of conceptual thought. As long as one is engaged in concepts, one is interacting with the conventional realm. Once all concepts have been eliminated by following the Buddhist path (as will be explained below), one realizes the ultimate truth. | + | The way in which one engages with the [[world]] determines whether one [[perceives]] things {{Wiki|conventionally}} or ultimately. The [[conventional truth]] involves [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]], [[logic]], and {{Wiki|reasoning}}, while [[the ultimate truth]] is outside of the [[realm]] of [[conceptual thought]]. As long as one is engaged in [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]], one is interacting with the [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[realm]]. Once all [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] have been eliminated by following the [[Buddhist path]] (as will be explained below), one realizes [[the ultimate truth]]. |

| − | Gorampa defines | + | [[Gorampa]] defines “[[conventional truth]]” as that which appears to [[ordinary beings]]: [[objects]], [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]], words, and so on. They are true in the [[sense]] that they appear to be true for ordinary persons, without any sort of [[philosophical]] analysis. Most [[people]], for example, can point to the Eiffel Tower and agree, “That is the Eiffel Tower.” The [[existence]] of the Eiffel Tower, therefore, is {{Wiki|conventionally}} true. It appears to ordinary, unenlightened [[people]], and these ordinary, unenlightened [[people]] identify it by means of the {{Wiki|linguistic}} convention, “Eiffel Tower.” |

| − | There are, of course, things that are understood by most ordinary beings to be false. If something is conventionally false, it appears incorrectly to the perspective of ordinary beings. | + | There are, of course, things that are understood by most [[ordinary beings]] to be false. If something is {{Wiki|conventionally}} false, it appears incorrectly to the {{Wiki|perspective}} of [[ordinary beings]]. |

| − | If a tourist in Paris drinks too much wine and starts seeing double, for example, this does not mean that there are suddenly two Eiffel Towers instead of one. The drunk person’s perception is simply skewed, and after he sobers up, he will once again see that really, there is only one Eiffel Tower. | + | If a tourist in {{Wiki|Paris}} drinks too much wine and starts [[seeing]] double, for example, this does not mean that there are suddenly two Eiffel Towers instead of one. The drunk person’s [[perception]] is simply skewed, and after he sobers up, he will once again see that really, there is only one Eiffel Tower. |

| − | To illustrate this point in his texts, Gorampa refers to Candrakīrti’s well-known Madhyamaka analogy of a person with an eye disorder (rab rib can) incorrectly seeing floating hairs on account of his impaired perception. The hairs are not really there, as a person with normally functioning eyes can affirm. | + | To illustrate this point in his texts, [[Gorampa]] refers to [[Candrakīrti’s]] well-known [[Madhyamaka]] analogy of a [[person]] with an [[eye]] disorder (rab rib can) incorrectly [[seeing]] floating hairs on account of his impaired [[perception]]. The hairs are not really there, as a [[person]] with normally functioning [[eyes]] can affirm. |

| − | The conventional truth, therefore, is true in the sense that it is something upon which all ordinary beings, who do not have impaired forms of perception, can agree. The conventional truth is what allows for ordinary persons to travel to Paris to visit the Eiffel Tower, to talk about the weather, and to engage in debates about politics. | + | The [[conventional truth]], therefore, is true in the [[sense]] that it is something upon which all [[ordinary beings]], who do not have impaired [[forms]] of [[perception]], can agree. The [[conventional truth]] is what allows for ordinary persons to travel to {{Wiki|Paris}} to visit the Eiffel Tower, to talk about the weather, and to engage in [[debates]] about {{Wiki|politics}}. |

| − | It is also, most importantly, what allows people to understand conceptually what a realization of the ultimate truth is like, and what enables practitioners to correctly develop logical reasoning and engage in proper types of meditative practices. | + | It is also, most importantly, what allows [[people]] to understand conceptually what a [[realization]] of [[the ultimate truth]] is like, and what enables practitioners to correctly develop [[logical]] {{Wiki|reasoning}} and engage in proper types of [[meditative practices]]. |

| − | In other words, some features of the conventional—such as reasoning and language—can be used to approach an understanding of the ultimate, even though the ultimate itself transcends those features. | + | In other words, some features of the conventional—such as {{Wiki|reasoning}} and language—can be used to approach an [[understanding]] of the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]], even though the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] itself {{Wiki|transcends}} those features. |

| − | In contrast to the conventional, the ultimate truth is understood as the way things really are, independent of the concepts and conventions with which ordinary persons engage. Gorampa contends that the conventional truth is mired in ignorance—the cause of saṃsāra, which keeps sentient beings cycling from lifetime to lifetime. | + | In contrast to the [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]], [[the ultimate truth]] is understood as [[the way things really are]], {{Wiki|independent}} of the [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] and conventions with which ordinary persons engage. [[Gorampa]] contends that the [[conventional truth]] is mired in ignorance—the [[cause]] of [[saṃsāra]], which keeps [[sentient beings]] cycling from [[lifetime]] to [[lifetime]]. |

| − | When this ignorance is removed, one is capable of realizing the ultimate truth, and through that realization, one can attain freedom from the cycle of rebirth. | + | When this [[ignorance]] is removed, one is capable of [[realizing]] [[the ultimate truth]], and through that [[realization]], one can attain freedom from the [[cycle of rebirth]]. |

| − | Based on this account, then, when ordinary, unenlightened persons talk about | + | Based on this account, then, when ordinary, unenlightened persons talk about “[[the ultimate truth]],” they necessarily identify it in terms of [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]]. This {{Wiki|conceptual}} [[understanding]] of [[the ultimate truth]], while not a [[direct realization]] of [[the ultimate truth]], is a crucial step on the [[Buddhist path]], linking ordinary persons to [[enlightened]] [[buddhas]]. Developing a [[concept of the ultimate]] is not [[enlightenment]] itself, but it gives one a [[sense]] of what [[enlightenment]] is like. |

| − | In order to explain the difference between a conceptual understanding and a nonconceptual realization of the ultimate truth, Gorampa divides it into two types: the ultimate that is taught (bstan pa'i don dam) and the ultimate that is realized (rtogs pa'i don dam). | + | In order to explain the difference between a {{Wiki|conceptual}} [[understanding]] and a [[nonconceptual]] [[realization]] of [[the ultimate truth]], [[Gorampa]] divides it into two types: the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] that is [[taught]] ([[bstan pa'i]] [[don dam]]) and the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] that is [[realized]] (rtogs pa'i [[don dam]]). |

| − | The ultimate that is taught corresponds to an ordinary person’s understanding of the ultimate, while the ultimate that is realized is directly perceived by enlightened beings. | + | The [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] that is [[taught]] corresponds to an ordinary person’s [[understanding]] of the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]], while the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] that is [[realized]] is directly [[perceived]] by [[enlightened beings]]. |

| − | Similarly, Gorampa contends that the conventional truth is also divided according to the perspective of ordinary and enlightened beings: the former perceive conventional truth (kun rdzob bden pa) while the latter understand it as mere convention (kun rdzob tsam). | + | Similarly, [[Gorampa]] contends that the [[conventional truth]] is also divided according to the {{Wiki|perspective}} of ordinary and [[enlightened beings]]: the former {{Wiki|perceive}} [[conventional truth]] ([[kun rdzob bden pa]]) while the [[latter]] understand it as mere convention ([[kun rdzob]] tsam). |

| − | Again, the conventional truth is that which is true for ordinary, unenlightened beings (such as the Eiffel Tower). Mere convention, on the other hand, is a term that corresponds to the perspective of enlightened beings. | + | Again, the [[conventional truth]] is that which is true for ordinary, [[unenlightened beings]] (such as the Eiffel Tower). Mere convention, on the other hand, is a term that corresponds to the {{Wiki|perspective}} of [[enlightened beings]]. |

| − | When highly realized beings (āryas, who are superior to ordinary beings on the Buddhist path, but not yet fully enlightened buddhas) engage in meditation (rnyam gzhag), they directly and nonconceptually perceive the ultimate truth. | + | When highly [[realized beings]] ([[āryas]], who are {{Wiki|superior}} to [[ordinary beings]] on the [[Buddhist path]], but not yet [[fully enlightened buddhas]]) engage in [[meditation]] (rnyam gzhag), they directly and nonconceptually {{Wiki|perceive}} [[the ultimate truth]]. |

| − | Once they emerge from their [[meditative states]] ([[rjes thob]]), however, they realize that the things that they had previously understood to be conventionally “true” are not actually true. | + | Once they emerge from their [[meditative states]] ([[rjes thob]]), however, they realize that the things that they had previously understood to be {{Wiki|conventionally}} “true” are not actually true. |

| − | After an ārya has directly realized the ultimate, conventional things appear as merely conventional. This mere convention is not false; it is simply understood as a mode of perception that is subordinated to the [[ultimate truth]] that has been directly experienced in meditation. | + | After an [[ārya]] has directly [[realized]] the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]], [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] things appear as merely [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]]. This mere convention is not false; it is simply understood as a mode of [[perception]] that is subordinated to the [[ultimate truth]] that has been directly [[experienced]] in [[meditation]]. |

| − | It is important to note that conventional objects, such as the Eiffel Tower, tables, persons, ideas, and so on, are the same regardless of whether their existences are understood as conventionally true or mere conventions. The difference between conventional truth and mere convention is based entirely on the subject who apprehends these objects. | + | It is important to note that [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[objects]], such as the Eiffel Tower, tables, persons, [[ideas]], and so on, are the same regardless of whether their [[existences]] are understood as {{Wiki|conventionally}} true or mere conventions. The difference between [[conventional truth]] and mere convention is based entirely on the [[subject]] who apprehends these [[objects]]. |

| − | The same table appears as truly existent to an ordinary being, and as a mere conceptual imputation to an [[ārya]]. (Tsongkhapa, on the other hand, distinguishes the two truths on the basis of the object, arguing that every object consists of an ultimate and a conventional aspect ([[ngo bo gcig la ldog pa tha dad]]). [[Tsongkhapa]] contends that these two aspects are not substantially different, but only differ conceptually. | + | The same table appears as [[truly existent]] to an ordinary being, and as a mere {{Wiki|conceptual}} [[imputation]] to an [[ārya]]. ([[Tsongkhapa]], on the other hand, distinguishes the [[two truths]] on the basis of the [[object]], arguing that every [[object]] consists of an [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] and a [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] aspect ([[ngo bo gcig la ldog pa tha dad]]). [[Tsongkhapa]] contends that these two aspects are not substantially different, but only differ conceptually. |

| − | Nevertheless, the important distinction here is that for Tsongkhapa, the difference between the two truths is made on the basis of the apprehended object (yul), while for Gorampa, the distinction is made on the basis of the mind of the apprehending subject (yul can). | + | Nevertheless, the important {{Wiki|distinction}} here is that for [[Tsongkhapa]], the difference between the [[two truths]] is made on the basis of the [[apprehended object]] (yul), while for [[Gorampa]], the {{Wiki|distinction}} is made on the basis of the [[mind]] of the apprehending [[subject]] ([[yul can]]). |

| − | With respect to the ultimate truth, the ultimate that is taught is an ordinary being’s conceptual understanding of what the ultimate truth is like. After studying Buddhist scriptures and learning philosophy, ordinary beings come to understand the ultimate truth in the Madyamaka sense as emptiness. | + | With [[respect]] to [[the ultimate truth]], the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] that is [[taught]] is an ordinary being’s {{Wiki|conceptual}} [[understanding]] of what [[the ultimate truth]] is like. After studying [[Buddhist scriptures]] and {{Wiki|learning}} [[philosophy]], [[ordinary beings]] come to understand [[the ultimate truth]] in the [[Madyamaka]] [[sense]] as [[emptiness]]. |

| − | The ultimate truth that is realized corresponds to that which is directly experienced by fully enlightened buddhas, and āryas in meditation. The real ultimate truth is free from all concepts, including the concepts of emptiness and interdependence. | + | The [[ultimate truth]] that is [[realized]] corresponds to that which is directly [[experienced]] by [[fully enlightened buddhas]], and [[āryas]] in [[meditation]]. The real [[ultimate truth]] is free from all [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]], [[including]] the [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] of [[emptiness]] and [[interdependence]]. |

| − | It is a state that is entirely nonconceptual, and is the end goal of the Buddhist path. | + | It is a [[state]] that is entirely [[nonconceptual]], and is the end goal of the [[Buddhist path]]. |

| − | In short, ordinary beings can understand the conventional truth, and the ultimate that is taught. Āryas in their post-meditative states, can understand mere convention. | + | In short, [[ordinary beings]] can understand the [[conventional truth]], and the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] that is [[taught]]. [[Āryas]] in their post-meditative states, can understand mere convention. |

| − | And Āryas in meditation and fully enlightened buddhas can directly, nonconceptually experience the ultimate that is realized, which is free from all concepts. On this model, the Buddhist path involves a process of transforming one’s perspective. One begins by correctly identifying and understanding the conventional truth. | + | And [[Āryas]] in [[meditation]] and [[fully enlightened buddhas]] can directly, nonconceptually [[experience]] the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] that is [[realized]], which is free from all [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]]. On this model, the [[Buddhist path]] involves a process of [[transforming]] one’s {{Wiki|perspective}}. One begins by correctly identifying and [[understanding]] the [[conventional truth]]. |

| − | Then, through logical reasoning and meditative practices, one gradually begins to realize that this so-called truth is merely conventional and that it is based entirely on concepts that are rooted in ignorance; in this way one comes to a conceptual understanding of the ultimate that is taught. | + | Then, through [[logical]] {{Wiki|reasoning}} and [[meditative practices]], one gradually begins to realize that this so-called [[truth]] is merely [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] and that it is based entirely on [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] that are rooted in [[ignorance]]; in this way one comes to a {{Wiki|conceptual}} [[understanding]] of the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] that is [[taught]]. |

| − | Through more analysis and practice still, one eventually leaves behind the mere convention and directly realizes the ultimate truth, which does not depend on ignorance and concepts. | + | Through more analysis and practice still, one eventually leaves behind the mere convention and directly realizes [[the ultimate truth]], which does not depend on [[ignorance]] and [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]]. |

| − | In other words, in the process of realizing the ultimate, a distinctive feature of this realization is that, even though it depends on concepts (and thus ignorance), it can be used to negate concepts and ignorance. | + | In other words, in the process of [[realizing]] the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]], a {{Wiki|distinctive}} feature of this [[realization]] is that, even though it depends on [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] (and thus [[ignorance]]), it can be used to negate [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] and [[ignorance]]. |

| − | Gorampa describes the ultimate that is realized in terms of freedom from conceptual constructs ([[spros pa dang bral ba]]). It should be noted that this is not, however, the same as simply not thinking. (Gorampa defends himself against accusations equating his method to mere non-thinking in his lta ba’i shan ‘byed.) Concepts must be eliminated on the Buddhist path, but they must be eliminated in specific ways. | + | [[Gorampa]] describes the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] that is [[realized]] in terms of freedom from {{Wiki|conceptual}} constructs ([[spros pa dang bral ba]]). It should be noted that this is not, however, the same as simply not [[thinking]]. ([[Gorampa]] defends himself against accusations equating his method to mere non-thinking in his lta ba’i [[shan ‘byed]].) Concepts must be eliminated on the [[Buddhist path]], but they must be eliminated in specific ways. |

| − | These specific ways involve both logical reasoning and meditative practices, eliminating concepts gradually, in stages. When no more concepts remain to be analyzed, no conceptual constructs remain. | + | These specific ways involve both [[logical]] {{Wiki|reasoning}} and [[meditative practices]], eliminating [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] gradually, in stages. When no more [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] remain to be analyzed, no {{Wiki|conceptual}} constructs remain. |

| − | As will be shown below, Gorampa outlines a very specific fourfold process for eliminating concepts in order to arrive at this desired state of nonconceptuality. | + | As will be shown below, [[Gorampa]] outlines a very specific fourfold process for eliminating [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] in order to arrive at this [[desired]] [[state]] of [[nonconceptuality]]. |

| − | 2.2 Negation | + | 2.2 {{Wiki|Negation}} |

| − | Gorampa employs a fourfold negation known as the tetralemma (mtha’ bzhi) in order to refute all concepts in their entirety. Use of the tetralemma as a tool in Buddhist philosophy can be traced to Nāgārjuna’s [[Mūlamadhyamakakārika]], in which he famously remarks, “Neither from itself, nor from another, nor from both, nor without a cause, does anything, anywhere, ever, arise” (MMK I:1). | + | [[Gorampa]] employs a [[fourfold negation]] known as the [[tetralemma]] ([[mtha’ bzhi]]) in order to refute all [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] in their entirety. Use of the [[tetralemma]] as a tool in [[Buddhist philosophy]] can be traced to [[Nāgārjuna’s]] [[Mūlamadhyamakakārika]], in which he famously remarks, “Neither from itself, nor from another, nor from both, nor without a [[cause]], does anything, anywhere, ever, arise” (MMK I:1). |

| − | This fourfold rejection of one extreme, its opposite, both, and neither, is adopted by later Mādhyamikas and is frequently used as a tool in order to demonstrate the Madhyamaka view. | + | This fourfold rejection of one extreme, its opposite, both, and neither, is adopted by later [[Mādhyamikas]] and is frequently used as a tool in order to demonstrate the [[Madhyamaka]] view. |

| − | Nāgārjuna’s commentator [[Āryadeva]] applies this fourfold negation to the extremes of existence, nonexistence, both, and neither in his Jñānasārasamuccaya, writing, “There is no existence, there is no nonexistence, there is no existence and nonexistence, nor is there the absence of both.” Gorampa frequently cites this passage in order to illustrate the Madhyamaka view as that which is free from conceptual constructs. | + | [[Nāgārjuna’s]] commentator [[Āryadeva]] applies this [[fourfold negation]] to the extremes of [[existence]], [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]], both, and neither in his [[Jñānasārasamuccaya]], [[writing]], “There is [[no existence]], there is no [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]], there is [[no existence]] and [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]], nor is there the absence of both.” [[Gorampa]] frequently cites this passage in order to illustrate the [[Madhyamaka]] view as that which is free from {{Wiki|conceptual}} constructs. |

| − | He contends that a proper understanding and application of this passage allows a practitioner to successfully transition from the state of an ordinary person who sees conventional truth, to an enlightened buddha who directly and nonconceptually realizes the ultimate. | + | He contends that a proper [[understanding]] and application of this passage allows a [[practitioner]] to successfully transition from the [[state]] of an [[ordinary person]] who sees [[conventional truth]], to an [[enlightened buddha]] who directly and nonconceptually realizes the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]]. |

| − | Most Tibetan Buddhist philosophers agree that the tetralemma is a tool that allows one to realize the ultimate, but they differ in their explanations of the ways in which this tool functions. | + | Most [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[philosophers]] agree that the [[tetralemma]] is a tool that allows one to realize the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]], but they differ in their explanations of the ways in which this tool functions. |

| − | Gorampa argues that one must negate each of the four extremes in succession by using logic and reasoning, and then one must subsequently realize the negation of all four extremes simultaneously through meditative practices. | + | [[Gorampa]] argues that one must negate each of the [[four extremes]] in succession by using [[logic and reasoning]], and then one must subsequently realize the {{Wiki|negation}} of all [[four extremes]] simultaneously through [[meditative practices]]. |

| − | 2.2.1 The Process of Refuting the Four Extremes | + | 2.2.1 The Process of Refuting the [[Four Extremes]] |

| − | Gorampa’s Synopsis indicates that one must begin the process of the fourfold negation by analyzing and refuting the concept of existence. This can be done by using the five Madhyamaka reasonings (gtan tshigs lnga). These five types of reasoning are: | + | [[Gorampa’s]] Synopsis indicates that one must begin the process of the [[fourfold negation]] by analyzing and refuting the {{Wiki|concept}} of [[existence]]. This can be done by using the five [[Madhyamaka]] reasonings ([[gtan tshigs lnga]]). These five types of {{Wiki|reasoning}} are: |

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | Neither one nor many (gcig du dral), which analyzes the essence (ngo bo) of things. | + | [[Neither one nor many]] ([[gcig du]] dral), which analyzes the [[essence]] ([[ngo bo]]) of things. |

| − | Diamond splinters (rdo rje'i gzegs ma), which analyzes causes. | + | [[Diamond]] splinters (rdo rje'i gzegs ma), which analyzes [[causes]]. |

| − | Refuting the arising of something existent or nonexistent (yod med skye ‘gog), which analyzes effects. | + | Refuting the [[arising]] of something [[existent]] or [[Wikipedia:Nothing|nonexistent]] ([[yod med]] skye ‘gog), which analyzes effects. |

| − | Refuting the four possibilities of arising (mu bzhi skye ‘gog), which analyzes causes and effects together. | + | Refuting the four possibilities of [[arising]] ([[mu bzhi]] skye ‘gog), which analyzes [[causes]] and effects together. |

| − | Dependent arising (rten ‘brel), which shows that phenomena cannot exist independently. | + | [[Dependent arising]] ([[rten ‘brel]]), which shows that [[phenomena]] cannot [[exist]] {{Wiki|independently}}. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

| − | These points are generally agreed upon by all Mādhyamikas, and entire essays can be devoted to each of these five types of reasoning, so they will not be discussed in detail here. | + | These points are generally agreed upon by all [[Mādhyamikas]], and entire {{Wiki|essays}} can be devoted to each of these five types of {{Wiki|reasoning}}, so they will not be discussed in detail here. |

| − | After one has successfully negated the first extreme, Gorampa concedes that a person’s natural inclination is to assume that the negation of existence implies the assertion of nonexistence. | + | After one has successfully negated the first extreme, [[Gorampa]] concedes that a person’s natural inclination is to assume that the [[negation of existence]] implies the [[assertion]] of [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]]. |

| − | If one were to stop his logical analysis at this point, Gorampa argues that one would adhere to a nihilist view; failure to correctly negate nonexistence can lead one to wrongly believe that nonexistence is ultimately real. | + | If one were to stop his [[logical analysis]] at this point, [[Gorampa]] argues that one would adhere to a [[Wikipedia:Nihilist|nihilist]] view; failure to correctly negate [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] can lead one to wrongly believe that [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] is [[ultimately real]]. |

| − | In order to show that the acceptance of nonexistence is untenable, Gorampa argues that the concepts of existence and nonexistence depend upon each other; one makes no sense without the other. And, since the concept of existence has already been negated, it makes no sense to conceive of nonexistence independently. | + | In order to show that the [[acceptance]] of [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] is untenable, [[Gorampa]] argues that the [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] of [[existence]] and [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] depend upon each other; one makes no [[sense]] without the other. And, since the {{Wiki|concept}} of [[existence]] has already been negated, it makes no [[sense]] to [[conceive]] of [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] {{Wiki|independently}}. |

| − | Once he has shown that existence and nonexistence are each untenable, Gorampa refutes the third extreme view, that things can somehow simultaneously both exist and not exist. He dismisses this possibility quite succinctly in his Synopsis, stating that if existence and nonexistence have each been refuted individually, then it makes no sense that they could somehow exist together. | + | Once he has shown that [[existence]] and [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] are each untenable, [[Gorampa]] refutes the third extreme view, that things can somehow simultaneously both [[exist]] and not [[exist]]. He dismisses this possibility quite succinctly in his Synopsis, stating that if [[existence]] and [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] have each been refuted individually, then it makes no [[sense]] that they could somehow [[exist]] together. |

| − | The refutation of the fourth extreme, neither existence nor nonexistence, yet again depends upon the successful refutation of the previous three. Gorampa argues that to conceive of something as “neither existent nor | + | The refutation of [[the fourth]] extreme, neither [[existence]] nor [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]], yet again depends upon the successful refutation of the previous three. [[Gorampa]] argues that to [[conceive]] of something as “neither [[existent]] nor [[Wikipedia:Nothing|nonexistent]]” is to [[conceive]] of something that is somewhere between the [[two extremes]] of [[existence]] and [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]]. |

| − | He contends, however, that if one has any concept of anything at all – even if it is some sort of concept of quasi-existence – this is still a wrong view. | + | He contends, however, that if one has any {{Wiki|concept}} of anything at all – even if it is some sort of {{Wiki|concept}} of quasi-existence – this is still a [[wrong view]]. |

| − | With the refutation of this fourth extreme, Gorampa shows that any possible way of conceiving of the ontological status of a thing, even something seemingly as convoluted as “things neither exist nor do not exist,” must be eliminated completely. If one is capable of conceiving of things as existing or not existing in any way whatsoever, then one cannot have a true, nonconceptual realization of the way things really are. | + | With the refutation of this fourth extreme, [[Gorampa]] shows that any possible way of [[conceiving]] of the [[Wikipedia:Ontology|ontological]] {{Wiki|status}} of a thing, even something seemingly as convoluted as “things neither [[exist]] nor do not [[exist]],” must be eliminated completely. If one is capable of [[conceiving]] of things as [[existing]] or not [[existing]] in any way whatsoever, then one cannot have a true, [[nonconceptual]] [[realization]] of [[the way things really are]]. |

| − | Gorampa contends that one must understand the refutation of each of these four concepts in succession; the logic that refutes the concept of nonexistence depends upon the successful refutation of the existence, the refutation of the third concept (both existence and nonexistence) depends on the refutation of the first two, and the refutation of the fourth (neither existence nor nonexistence) depends upon the refutation of the first three concepts. | + | [[Gorampa]] contends that one must understand the refutation of each of these four [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] in succession; the [[logic]] that refutes the {{Wiki|concept}} of [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] depends upon the successful refutation of the [[existence]], the refutation of the third {{Wiki|concept}} (both [[existence]] and [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]]) depends on the refutation of the first two, and the refutation of [[the fourth]] (neither [[existence]] nor [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]]) depends upon the refutation of the first three [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]]. |

| − | Existence, nonexistence, both, and neither are the only possible ways of conceiving of the status of a thing, so once each of these possible ways are eliminated, there is no way to conceive of things anymore. | + | [[Existence]], [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]], both, and neither are the only possible ways of [[conceiving]] of the {{Wiki|status}} of a thing, so once each of these possible ways are eliminated, there is no way to [[conceive]] of things anymore. |

| − | The process of negating the four extreme views also involves meditative practices. Gorampa argues that along with conducting a thorough philosophical analysis, one must meditate on the refutation of each of the four extremes individually, in succession. Then, one will come to directly realize all four negations simultaneously. | + | The process of negating the four extreme [[views]] also involves [[meditative practices]]. [[Gorampa]] argues that along with conducting a thorough [[philosophical]] analysis, one must [[meditate]] on the refutation of each of the [[four extremes]] individually, in succession. Then, one will come to directly realize all four negations simultaneously. |

| − | One way to understand this style of meditative practice is in terms of a “turning off” of concepts. | + | One way to understand this style of [[meditative practice]] is in terms of a “turning off” of [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]]. |

| − | After one conceptually understands the negation of things existing inherently, for example, one meditates on this negation and eventually stops having concepts of things existing altogether. This process continues through all four possibilities in the tetralemma, until one no longer conceives of things at all. Again, it is important to note that this is distinct from simply arresting the process of thought. | + | After one conceptually [[understands]] the {{Wiki|negation}} of things [[existing]] inherently, for example, one [[meditates]] on this {{Wiki|negation}} and eventually stops having [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] of things [[existing]] altogether. This process continues through all four possibilities in the [[tetralemma]], until one no longer conceives of things at all. Again, it is important to note that this is {{Wiki|distinct}} from simply arresting the process of [[thought]]. |

| Line 331: | Line 331: | ||

| − | 2.2.2 The Role of Negation and the Function of the [[Tetralemma]] | + | 2.2.2 The Role of {{Wiki|Negation}} and the Function of the [[Tetralemma]] |

| − | Gorampa understands the tetralemma as a tool that one uses to analyze the ultimate truth. One uses logic and reasoning to arrive at a conceptual understanding of the ultimate that is taught, and meditative practices allow one to reach a direct, nonconceptual realization of the ultimate truth. | + | [[Gorampa]] [[understands]] the [[tetralemma]] as a tool that one uses to analyze [[the ultimate truth]]. One uses [[logic and reasoning]] to arrive at a {{Wiki|conceptual}} [[understanding]] of the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] that is [[taught]], and [[meditative practices]] allow one to reach a direct, [[nonconceptual]] [[realization]] of [[the ultimate truth]]. |

| − | The logical reasoning involved in the fourfold negation is implemented by ordinary persons in order to understand what the ultimate truth is like, but logic alone is not sufficient to arrive at a direct realization of the ultimate. | + | The [[logical]] {{Wiki|reasoning}} involved in the [[fourfold negation]] is implemented by ordinary persons in order to understand what [[the ultimate truth]] is like, but [[logic]] alone is not sufficient to arrive at a [[direct realization]] of the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]]. |

| − | This particular way of understanding the tetralemma is, again, at odds with the views of Tsongkhapa. Tsongkhapa contends that Gorampa’s assertion that all concepts must be eliminated entirely amounts to nihilistic quietism. | + | This particular way of [[understanding]] the [[tetralemma]] is, again, at odds with the [[views]] of [[Tsongkhapa]]. [[Tsongkhapa]] contends that [[Gorampa’s]] [[assertion]] that all [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] must be eliminated entirely amounts to [[Wikipedia:Nihilism|nihilistic]] quietism. |

| − | Tsongkhapa understands each of the four extremes of the tetralemma as being qualified according to the conventional or ultimate truths. According to him, existence is negated ultimately, while nonexistence is negated conventionally. | + | [[Tsongkhapa]] [[understands]] each of the [[four extremes]] of the [[tetralemma]] as being qualified according to the [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] or [[ultimate truths]]. According to him, [[existence]] is negated ultimately, while [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] is negated {{Wiki|conventionally}}. |

| − | This debate between Gorampa and Tsongkhapa is based on each philosopher’s understanding of the ways in which negation functions within the tetralemma. Tsongkhapa upholds the law of double negation elimination ([[dgag pa gnyis kyi rnal ma go ba]]), a logical law stating that the negation of a negation implies an affirmation. | + | This [[debate]] between [[Gorampa]] and [[Tsongkhapa]] is based on each philosopher’s [[understanding]] of the ways in which {{Wiki|negation}} functions within the [[tetralemma]]. [[Tsongkhapa]] upholds the law of double {{Wiki|negation}} elimination ([[dgag pa gnyis kyi rnal ma go ba]]), a [[logical]] law stating that the {{Wiki|negation}} of a {{Wiki|negation}} implies an [[affirmation]]. |

| − | The negation of existence, therefore, implies the acceptance of nonexistence, while the negation of nonexistence implies the assertion of existence. | + | The [[negation of existence]], therefore, implies the [[acceptance]] of [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]], while the {{Wiki|negation}} of [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] implies the [[assertion]] of [[existence]]. |

| − | Because of this, Tsongkhapa’s understanding of the tetralemma involves a complex system of logical statements, each qualified according to one of the two truths. If one accepts double negation elimination, then it makes no sense for both existence and nonexistence to be negated, unless these negations are qualified in certain ways. | + | Because of this, [[Tsongkhapa’s]] [[understanding]] of the [[tetralemma]] involves a complex system of [[logical]] statements, each qualified according to one of the [[two truths]]. If one accepts double {{Wiki|negation}} elimination, then it makes no [[sense]] for both [[existence]] and [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] to be negated, unless these negations are qualified in certain ways. |

| − | Gorampa, on the other hand, does not adhere to double negation in the context of the tetralemma. Instead, he understands the tetralemma as a succession of four negations that are applied to the four possible ways of conceiving of the status of the ultimate truth. | + | [[Gorampa]], on the other hand, does not adhere to double {{Wiki|negation}} in the context of the [[tetralemma]]. Instead, he [[understands]] the [[tetralemma]] as a succession of four negations that are applied to the four possible ways of [[conceiving]] of the {{Wiki|status}} of [[the ultimate truth]]. |

| − | Because the ultimate truth is nonconceptualizable, Gorampa contends that Tsongkhapa’s understanding of the tetralemma is incomplete, because it doesn’t negate enough (literally, it underpervades [khyab chung ba]). | + | Because [[the ultimate truth]] is nonconceptualizable, [[Gorampa]] contends that [[Tsongkhapa’s]] [[understanding]] of the [[tetralemma]] is incomplete, because it doesn’t negate enough (literally, it underpervades [[[khyab chung ba]]]). |

| − | While Tsongkhapa’s model successfully refutes the extreme view of existence at the ultimate level, Gorampa argues that it does not eliminate all extreme views ultimately and in their entirety. | + | While [[Tsongkhapa’s]] model successfully refutes the extreme view of [[existence]] at the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] level, [[Gorampa]] argues that it does not eliminate all extreme [[views]] ultimately and in their entirety. |

| − | Tsongkhapa argues that a negation of all four extremes at the ultimate level contradicts logic, but Gorampa contends that an elimination of logic is specifically the tetralemma’s purpose. | + | [[Tsongkhapa]] argues that a {{Wiki|negation}} of all [[four extremes]] at the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] level contradicts [[logic]], but [[Gorampa]] contends that an elimination of [[logic]] is specifically the tetralemma’s {{Wiki|purpose}}. |

| − | By negating all possibilities for logical, conceptual thought, the only recourse is to abandon concepts completely. True freedom from conceptual constructs lies outside of the scope of conceptual thought, and is therefore inexpressible. | + | By negating all possibilities for [[logical]], [[conceptual thought]], the only recourse is to abandon [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] completely. True freedom from {{Wiki|conceptual}} constructs lies outside of the scope of [[conceptual thought]], and is therefore inexpressible. |

| − | Gorampa maintains, however, that because ordinary persons utilize conceptual thought, they necessarily construe the ultimate truth as an object of conceptual constructs (that is, they construe it as the ultimate that is taught). As such, one must first use conceptual reasoning to refute each of the four extremes, but these concepts must eventually be abandoned. | + | [[Gorampa]] maintains, however, that because ordinary persons utilize [[conceptual thought]], they necessarily construe [[the ultimate truth]] as an [[object]] of {{Wiki|conceptual}} constructs (that is, they construe it as the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] that is [[taught]]). As such, one must first use {{Wiki|conceptual}} {{Wiki|reasoning}} to refute each of the [[four extremes]], but these [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] must eventually be abandoned. |

| − | In other words, because all four extremes are negated under the analysis of the tetralemma, Gorampa concludes that a correct realization of the ultimate truth must be something that is other than these conceptualizations of and dichotomizations into existence and nonexistence. As such, the ultimate truth cannot be described using these terms. | + | In other words, because all [[four extremes]] are negated under the analysis of the [[tetralemma]], [[Gorampa]] concludes that a correct [[realization]] of [[the ultimate truth]] must be something that is other than these [[conceptualizations]] of and dichotomizations into [[existence]] and [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]]. As such, [[the ultimate truth]] cannot be described using these terms. |

| − | And, since these are the only possible ways of speaking of or conceptualizing the status of the existence of things, once they are all negated, one is forced to conclude that the ultimate truth cannot be described linguistically or conceptually. | + | And, since these are the only possible ways of {{Wiki|speaking}} of or [[conceptualizing]] the {{Wiki|status}} of the [[existence]] of things, once they are all negated, one is forced to conclude that [[the ultimate truth]] cannot be described linguistically or conceptually. |

| − | The ultimate truth that is realized transcends the boundaries of language and conceptual thought. However, Gorampa still maintains that logic and analysis are essential in arriving at a state of nonconceptuality. | + | The [[ultimate truth]] that is [[realized]] {{Wiki|transcends}} the [[boundaries]] of [[language]] and [[conceptual thought]]. However, [[Gorampa]] still maintains that [[logic]] and analysis are [[essential]] in arriving at a [[state]] of [[nonconceptuality]]. |

| − | 2.3 The Role of Logic | + | 2.3 The Role of [[Logic]] |

| − | Gorampa’s understanding of the relationship between the two truths and the use of negation in the tetralemma inform his understanding of the ways in which a practitioner should proceed on the Buddhist path. | + | [[Gorampa’s]] [[understanding]] of the relationship between the [[two truths]] and the use of {{Wiki|negation}} in the [[tetralemma]] inform his [[understanding]] of the ways in which a [[practitioner]] should proceed on the [[Buddhist path]]. |

| − | The end result of this path, enlightenment, is the ultimate goal toward which all Buddhists strive. Gorampa’s arguments regarding the above points therefore inform the ways in which one should understand the nature of this end result. | + | The end result of this [[path]], [[enlightenment]], is the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] goal toward which all [[Buddhists]] strive. [[Gorampa’s]] arguments regarding the above points therefore inform the ways in which one should understand the [[nature]] of this end result. |

| − | According to Gorampa, concepts come from ignorance, and the path of eliminating ignorance involves eliminating concepts. | + | According to [[Gorampa]], [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] come from [[ignorance]], and the [[path]] of eliminating [[ignorance]] involves eliminating [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]]. |

| − | In other words, since a buddha is completely free of ignorance, he has no concepts whatsoever. This claim is quite controversial for obvious reasons: buddhas are understood as consisting of perfect wisdom, and are described in scriptures as omniscient beings. How, then, can a buddha have no concepts at all, but still be considered omniscient? | + | In other words, since a [[buddha]] is completely free of [[ignorance]], he has no [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] whatsoever. This claim is quite controversial for obvious [[reasons]]: [[buddhas]] are understood as consisting of [[perfect wisdom]], and are described in [[scriptures]] as [[omniscient]] [[beings]]. How, then, can a [[buddha]] have no [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] at all, but still be considered [[omniscient]]? |

| − | Gelugpa opponents criticize Gorampa for this very reason. They contend that Gorampa’s philosophy negates too much (literally “overpervades” [khyab che ba]). If the end result is a complete elimination of concepts, then one could attain enlightenment by simply falling asleep or otherwise becoming unconscious. | + | [[Gelugpa]] opponents criticize [[Gorampa]] for this very [[reason]]. They contend that [[Gorampa’s]] [[philosophy]] negates too much (literally “overpervades” [[[khyab che ba]]]). If the end result is a complete elimination of [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]], then one could [[attain enlightenment]] by simply falling asleep or otherwise becoming [[unconscious]]. |

| − | Gorampa contends, however, that in order to successfully eliminate all concepts in their entirety, it is absolutely essential that one begins by using logic and reasoning. The end result is indeed nonconceptual, but it differs from the quietism that is a result of simply not-thinking, without any prior analysis. | + | [[Gorampa]] contends, however, that in order to successfully eliminate all [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] in their entirety, it is absolutely [[essential]] that one begins by using [[logic and reasoning]]. The end result is indeed [[nonconceptual]], but it differs from the quietism that is a result of simply not-thinking, without any prior analysis. |

| − | The issue underlying this debate concerns the conceptual content of fully enlightened buddhas. Gorampa contends, citing Candrakīrti, that fully enlightened buddhas have no conceptual content whatsoever; they have completely eliminated ignorance in its entirety, and therefore do not actively engage in the conventional world. They do not conceive of things as existent, nonexistent, both, or neither. | + | The issue underlying this [[debate]] concerns the {{Wiki|conceptual}} content of [[fully enlightened buddhas]]. [[Gorampa]] contends, citing [[Candrakīrti]], that [[fully enlightened buddhas]] have no {{Wiki|conceptual}} content whatsoever; they have completely eliminated [[ignorance]] in its entirety, and therefore do not actively engage in the [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[world]]. They do not [[conceive]] of things as [[existent]], [[Wikipedia:Nothing|nonexistent]], both, or neither. |

| − | In fact, they do not conceive of things at all. They do, however, appear omniscient from the perspective of ordinary beings, and because of their previous karma and the compassion that they have cultivated on the path to enlightenment, they continue to function in the world for the benefit of ordinary unenlightened beings for a period of time. | + | In fact, they do not [[conceive]] of things at all. They do, however, appear [[omniscient]] from the {{Wiki|perspective}} of [[ordinary beings]], and because of their previous [[karma]] and the [[compassion]] that they have cultivated on the [[path to enlightenment]], they continue to function in the [[world]] for the [[benefit]] of ordinary [[unenlightened beings]] for a period of time. |

| − | The implications of Gorampa’s view are significant. On Tsongkhapa’s model, certain concepts (i.e., concepts about emptiness) are the right kinds of concepts, which means that if one has not carefully constructed the right kinds of concepts in the right ways, one will not attain enlightenment. | + | The implications of [[Gorampa’s]] view are significant. On [[Tsongkhapa’s]] model, certain [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] (i.e., [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] about [[emptiness]]) are the right kinds of [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]], which means that if one has not carefully [[constructed]] the right kinds of [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] in the right ways, one will not [[attain enlightenment]]. |

| − | On Gorampa’s model, as long as one uses logic and reasoning to refute the ignorance that gives rise to concepts, one can attain enlightenment. While Tsongkhapa’s model espouses one specific view that must be cultivated in one specific way, Gorampa’s model leaves open the possibility for different practitioners to employ different styles of reasoning. | + | On [[Gorampa’s]] model, as long as one uses [[logic and reasoning]] to refute the [[ignorance]] that gives rise to [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]], one can [[attain enlightenment]]. While [[Tsongkhapa’s]] model espouses one specific view that must be cultivated in one specific way, [[Gorampa’s]] model leaves open the possibility for different practitioners to employ different styles of {{Wiki|reasoning}}. |

| − | 2.4 Methods of Argumentation | + | 2.4 [[Methods]] of Argumentation |

| − | Gorampa’s articulation of the idea that there are different styles of reasoning that are capable of leading to enlightenment on the Buddhist path exists in the context of his assessment of the difference between the so-called Prāsaṅgika and Svātantrika schools of Madhyamaka thought. | + | [[Gorampa’s]] articulation of the [[idea]] that there are different styles of {{Wiki|reasoning}} that are capable of leading to [[enlightenment]] on the [[Buddhist path]] [[exists]] in the context of his assessment of the difference between the so-called [[Prāsaṅgika]] and [[Svātantrika]] schools of [[Madhyamaka]] [[thought]]. |

| − | These two subschools were understood by Tibetan thinkers as being developed by the Indian Mādhyamikas Buddhapālita and Bhāviveka, the former advocating the Prāsaṅgika position and the latter that of the Svātantrika. | + | These two subschools were understood by [[Tibetan]] thinkers as being developed by the [[Indian]] [[Mādhyamikas]] [[Buddhapālita]] and [[Bhāviveka]], the former advocating the [[Prāsaṅgika]] position and the [[latter]] that of the [[Svātantrika]]. |

| − | Candrakīrti is understood as upholding the Prāsaṅgika tradition, because he defended Buddhapālita’s views against Bhāviveka’s criticisms. It is important to note, however, that none of these Indian scholars labeled themselves as adherents of particular subschools of Madhyamaka, and that the terms rang gyud pa (Svātantrika) and thal ‘gyur ba (Prāsaṅgika) were coined centuries later by Tibetans. | + | [[Candrakīrti]] is understood as upholding the [[Prāsaṅgika]] [[tradition]], because he defended [[Buddhapālita’s]] [[views]] against [[Bhāviveka’s]] {{Wiki|criticisms}}. It is important to note, however, that none of these [[Indian]] [[scholars]] labeled themselves as {{Wiki|adherents}} of particular subschools of [[Madhyamaka]], and that the terms [[rang gyud]] pa ([[Svātantrika]]) and [[thal ‘gyur ba]] ([[Prāsaṅgika]]) were coined centuries later by [[Tibetans]]. |

| − | (Western scholars, moreover, have contributed to the misconception that these two schools actually existed in India by Sanskritizing these Tibetan terms.) | + | ([[Western]] [[scholars]], moreover, have contributed to the {{Wiki|misconception}} that these two schools actually existed in [[India]] by Sanskritizing these [[Tibetan]] terms.) |

| − | Regardless of whether Buddhapālita, Bhāviveka, or Candrakīrti actually understood themselves as advocating these distinct positions, the distinction between Svātantrika and Prāsaṅgika became reified in medieval Tibetan Buddhist discourse. | + | Regardless of whether [[Buddhapālita]], [[Bhāviveka]], or [[Candrakīrti]] actually understood themselves as advocating these {{Wiki|distinct}} positions, the {{Wiki|distinction}} between [[Svātantrika]] and [[Prāsaṅgika]] became reified in {{Wiki|medieval}} [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[discourse]]. |

| − | Because Tibetans held Candrakīrti’s Madhyamaka in high regard, they purported to be Prāsaṅgikas themselves, and many constructed detailed explanations of the division between the Svātantrika and Prāsaṅgika systems, always upholding Prāsaṅgika as the highest form of Madhyamaka. | + | Because [[Tibetans]] held [[Candrakīrti’s]] [[Madhyamaka]] in high regard, they purported to be [[Prāsaṅgikas]] themselves, and many [[constructed]] detailed explanations of the [[division]] between the [[Svātantrika]] and [[Prāsaṅgika]] systems, always upholding [[Prāsaṅgika]] as the [[highest]] [[form]] of [[Madhyamaka]]. |

| − | Tsongkhapa composed a list of | + | [[Tsongkhapa]] composed a list of “[[eight difficult points]]” (dka’ gnad brgyad) distinguishing his [[own]] [[Prāsaṅgika]] view from that of the [[Svātantrika]]. Many of these points are quite technical, and the details of this list will not be addressed here. |

| − | The important point to consider is that based on these eight points, Tsongkhapa considers the two schools to differ in terms of their views regarding the nature of the ultimate truth. Based on these eight points, Tsongkhapa argues that the Prāsaṅgika view is superior to that of the Svātantrika. | + | The important point to consider is that based on these eight points, [[Tsongkhapa]] considers the two schools to differ in terms of their [[views]] regarding the [[nature]] of [[the ultimate truth]]. Based on these eight points, [[Tsongkhapa]] argues that the [[Prāsaṅgika]] view is {{Wiki|superior}} to that of the [[Svātantrika]]. |

| − | Gorampa similarly considers himself a Prāsaṅgika, but disagrees with Tsongkhapa on nearly all eight of his “difficult points.” | + | [[Gorampa]] similarly considers himself a [[Prāsaṅgika]], but disagrees with [[Tsongkhapa]] on nearly all eight of his “difficult points.” |

| − | Because his views regarding the two truths and negation inform a process whereby the Mādhyamika begins with logic and analysis, but ends in a state of nonconceptuality, Gorampa contends that there can be no differences between Mādhyamikas with respect to their final view. | + | Because his [[views]] regarding the [[two truths]] and {{Wiki|negation}} inform a process whereby the [[Mādhyamika]] begins with [[logic]] and analysis, but ends in a [[state]] of [[nonconceptuality]], [[Gorampa]] contends that there can be no differences between [[Mādhyamikas]] with [[respect]] to their final view. |

| − | There cannot be different types of nonconceptuality; freedom from conceptual constructs is freedom from conceptual constructs. The differences between these Madhyamaka subschools, therefore, occur with respect to the ways in which they understand the conventional truth, and utilize logic and reasoning. | + | There cannot be different types of [[nonconceptuality]]; freedom from {{Wiki|conceptual}} constructs is freedom from {{Wiki|conceptual}} constructs. The differences between these [[Madhyamaka]] subschools, therefore, occur with [[respect]] to the ways in which they understand the [[conventional truth]], and utilize [[logic and reasoning]]. |

| − | Gorampa’s refutations of Tsongkhapa’s eight points are especially technical, and a considerable portion of his Madhyamaka texts are devoted to articulating the nature of the differences between these two views. (Almost one third of his Synopsis, for example, is devoted to setting out the distinction between these two schools.) | + | [[Gorampa’s]] refutations of [[Tsongkhapa’s]] eight points are especially technical, and a considerable portion of his [[Madhyamaka]] texts are devoted to articulating the [[nature]] of the differences between these two [[views]]. (Almost one third of his Synopsis, for example, is devoted to setting out the {{Wiki|distinction}} between these two schools.) |

| − | The essence of Gorampa’s argument is that Svātantrikas utilize “autonomous | + | The [[essence]] of [[Gorampa’s]] argument is that [[Svātantrikas]] utilize “autonomous [[syllogisms]]” to argue for [[emptiness]], while [[Prāsaṅgikas]] do not. Because both schools assert that a [[realization]] of [[the ultimate truth]] involves freedom from all {{Wiki|conceptual}} constructs ([[spros bral]]), as long as one is in such a [[state]], one can realize the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]]. |

| − | There is no such thing as correct and incorrect spros bral. Once one has successfully arrived at this state, the methods that he has used to get there are no longer relevant. | + | There is no such thing as correct and incorrect [[spros bral]]. Once one has successfully arrived at this [[state]], the [[methods]] that he has used to get there are no longer relevant. |

| − | To use an analogy: suppose that a person wishes to drive from New York City to Boston. Depending on the kind of car that she is accustomed to driving, she can travel in a car with either manual or automatic transmission. | + | To use an analogy: suppose that a [[person]] wishes to drive from {{Wiki|New York City}} to [[Boston]]. Depending on the kind of car that she is accustomed to driving, she can travel in a car with either manual or automatic [[transmission]]. |

| − | Once she has arrived in Boston, the type of car that she drove no longer matters, even though she would have had to drive differently along the way. | + | Once she has arrived in [[Boston]], the type of car that she drove no longer matters, even though she would have had to drive differently along the way. |

| − | In the same way, if spros bral is the desired destination at the end of the Buddhist path, then depending on the ways in which one is accustomed to reasoning, one can successfully follow the Svātantrika or the Prāsaṅgika method in order to arrive at the same result. | + | In the same way, if [[spros bral]] is the [[desired]] destination at the end of the [[Buddhist path]], then depending on the ways in which one is accustomed to {{Wiki|reasoning}}, one can successfully follow the [[Svātantrika]] or the [[Prāsaṅgika]] method in order to arrive at the same result. |

| − | Gorampa still contends, however, that the Prāsaṅgika method of reasoning is a more efficient way of arriving at that result. Once one is in a state of spros bral, however, the type of reasoning that he used to get there no longer matters. | + | [[Gorampa]] still contends, however, that the [[Prāsaṅgika]] method of {{Wiki|reasoning}} is a more efficient way of arriving at that result. Once one is in a [[state]] of [[spros bral]], however, the type of {{Wiki|reasoning}} that he used to get there no longer matters. |

| − | Gorampa’s particular brand of Madhyamaka is characterized by his understanding of the two truths and negation, as shown above. Because the ultimate truth is entirely free from concepts, one utilizes negation to eliminate all concepts in their entirety. | + | [[Gorampa’s]] particular brand of [[Madhyamaka]] is characterized by his [[understanding]] of the [[two truths]] and {{Wiki|negation}}, as shown above. Because [[the ultimate truth]] is entirely free from [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]], one utilizes {{Wiki|negation}} to eliminate all [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] in their entirety. |