Difference between revisions of "Grief"

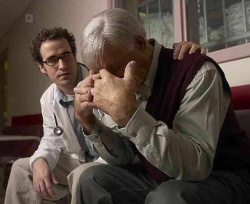

(Created page with "thumb|250px| Grief (''soka'') is a feeling of deep sadness experiences on losing something or someone loved. The period during which a person feels grief...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Grief.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Grief.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Grief (''soka'') is a feeling of deep sadness experiences on losing something or someone loved. The period during which a person feels grief is called mourning (''sacana''). If a person dies after a long illness, the grief felt by their family and relatives is usually far less because they have had time to prepare for the death. But some deaths are sudden and unexpected. The different reactions to a sudden or tragic death are well illustrated by what happened when the Buddha died. ‘Those monks who were not yet freed from the passions, wept, tore their hair, threw up their arms and rolled about on the ground .... But those monks who were free from craving, endured mindfully and clearly aware, saying, “All compounded things are impermanent so what is the use of all this?”’ (D.II,157). This first type of reaction might be called demonstrative grieving and the second quiet grieving. | + | |

| − | Sometimes this first type of grieving is due in part to social expectations or the desire to attract sympathy or attention. When genuine, it serves as a catharsis and a way to channel emotions into non-destructive paths. Nonetheless, it can be an extremely painful experience. For most people, even such intense grief usually fades after a while and they return to their normal state. But for some it persists and can cause a loss of interest in normal activities, long-term sadness and moping and even to depression. Quiet grieving can be due to suppressing one’s feelings, either to conform to social expectations or out of fear of appearing soft or vulnerable. At its best, however, quiet grieving can be indicative of emotional strength and a mature acceptance of life’s realities. | + | |

| − | Of course, better than strategies to deal with grief after it arises, is to prepare for it before it does. Nothing in life is as utterly predictable and absolutely certain than death, and yet it is the one contingency that we rarely prepare for. The Buddha recommended the practice of occasionally reflecting on the certainty of our own and our loved ones demise. This can lessen the intensity and the duration of grief when we experience it. An acceptance of the truth of rebirth can likewise be helpful. Understanding that our deceased loved ones had a life and a family before we came into contact with them, and that they will probably go on to a new life with a new family when they are reborn, can likewise lessen the pain of grief. | + | [[Grief]] (''[[soka]]'') is a [[feeling]] of deep [[sadness]] [[experiences]] on losing something or someone loved. |

| − | However, at least some sense of sadness at losing a loved one is inevitable. Even the Buddha experienced mild grief, or at least a sense of loss, after his two best friends and chief disciples, Moggallāna and Sāriputta, passed away. He said: | + | |

| + | The period during which a [[person]] [[feels]] [[grief]] is called [[mourning]] (''sacana''). | ||

| + | |||

| + | If a [[person]] [[dies]] after a long {{Wiki|illness}}, the [[grief]] felt by their [[family]] and relatives is usually far less because they have had time to prepare for the [[death]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But some [[deaths]] are sudden and unexpected. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The different reactions to a sudden or tragic [[death]] are well illustrated by what happened when the [[Buddha]] [[died]]. ‘Those [[monks]] who were not yet freed from the [[passions]], wept, tore their [[hair]], threw up their arms and rolled about on the ground .... | ||

| + | |||

| + | But those [[monks]] who were free from [[craving]], endured mindfully and clearly {{Wiki|aware}}, saying, “All [[compounded]] things are [[impermanent]] so what is the use of all this?”’ (D.II,157). This first type of {{Wiki|reaction}} might be called demonstrative grieving and the second quiet grieving. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Sometimes this first type of grieving is due in part to {{Wiki|social}} expectations or the [[desire]] to attract [[sympathy]] or [[attention]]. When genuine, it serves as a {{Wiki|catharsis}} and a way to [[channel]] [[emotions]] into non-destructive [[paths]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nonetheless, it can be an extremely [[painful]] [[experience]]. For most [[people]], even such intense [[grief]] usually fades after a while and they return to their normal [[state]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But for some it persists and can [[cause]] a loss of [[interest]] in normal [[activities]], long-term [[sadness]] and moping and even to {{Wiki|depression}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Quiet grieving can be due to suppressing one’s [[feelings]], either to conform to {{Wiki|social}} expectations or out of {{Wiki|fear}} of appearing soft or vulnerable. | ||

| + | |||

| + | At its best, however, quiet grieving can be indicative of [[emotional]] strength and a mature [[acceptance]] of life’s [[realities]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Of course, better than strategies to deal with [[grief]] after it arises, is to prepare for it before it does. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Nothing in [[life]] is as utterly predictable and absolutely certain than [[death]], and yet it is the one contingency that we rarely prepare for. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Buddha]] recommended the practice of occasionally {{Wiki|reflecting}} on the {{Wiki|certainty}} of our [[own]] and our loved ones demise. This can lessen the intensity and the duration of [[grief]] when we [[experience]] it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | An [[acceptance]] of the [[truth]] of [[rebirth]] can likewise be helpful. [[Understanding]] that our deceased loved ones had a [[life]] and a [[family]] before we came into [[contact]] with them, and that they will probably go on to a new [[life]] with a new [[family]] when they are [[reborn]], can likewise lessen the [[pain]] of [[grief]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | However, at least some [[sense]] of [[sadness]] at losing a loved one is inevitable. Even the [[Buddha]] [[experienced]] mild [[grief]], or at least a [[sense]] of loss, after his two best friends and chief [[disciples]], [[Moggallāna]] and [[Sāriputta]], passed away. He said: ‘[[Monks]], this assembly seems [[empty]] to me now that [[Moggallāna]] and [[Sāriputta]] have [[attained]] final [[Nirvāṇa]].’ (S.V,164). | ||

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

[http://www.buddhisma2z.com/content.php?id=160 www.buddhisma2z.com] | [http://www.buddhisma2z.com/content.php?id=160 www.buddhisma2z.com] | ||

[[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | [[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | ||

[[Category:Death & Rebirth]] | [[Category:Death & Rebirth]] | ||

Latest revision as of 01:30, 5 January 2016

Grief (soka) is a feeling of deep sadness experiences on losing something or someone loved.

The period during which a person feels grief is called mourning (sacana).

If a person dies after a long illness, the grief felt by their family and relatives is usually far less because they have had time to prepare for the death.

But some deaths are sudden and unexpected.

The different reactions to a sudden or tragic death are well illustrated by what happened when the Buddha died. ‘Those monks who were not yet freed from the passions, wept, tore their hair, threw up their arms and rolled about on the ground ....

But those monks who were free from craving, endured mindfully and clearly aware, saying, “All compounded things are impermanent so what is the use of all this?”’ (D.II,157). This first type of reaction might be called demonstrative grieving and the second quiet grieving.

Sometimes this first type of grieving is due in part to social expectations or the desire to attract sympathy or attention. When genuine, it serves as a catharsis and a way to channel emotions into non-destructive paths.

Nonetheless, it can be an extremely painful experience. For most people, even such intense grief usually fades after a while and they return to their normal state.

But for some it persists and can cause a loss of interest in normal activities, long-term sadness and moping and even to depression.

Quiet grieving can be due to suppressing one’s feelings, either to conform to social expectations or out of fear of appearing soft or vulnerable.

At its best, however, quiet grieving can be indicative of emotional strength and a mature acceptance of life’s realities.

Of course, better than strategies to deal with grief after it arises, is to prepare for it before it does.

Nothing in life is as utterly predictable and absolutely certain than death, and yet it is the one contingency that we rarely prepare for.

The Buddha recommended the practice of occasionally reflecting on the certainty of our own and our loved ones demise. This can lessen the intensity and the duration of grief when we experience it.

An acceptance of the truth of rebirth can likewise be helpful. Understanding that our deceased loved ones had a life and a family before we came into contact with them, and that they will probably go on to a new life with a new family when they are reborn, can likewise lessen the pain of grief.

However, at least some sense of sadness at losing a loved one is inevitable. Even the Buddha experienced mild grief, or at least a sense of loss, after his two best friends and chief disciples, Moggallāna and Sāriputta, passed away. He said: ‘Monks, this assembly seems empty to me now that Moggallāna and Sāriputta have attained final Nirvāṇa.’ (S.V,164).