Mahamudra and Dzogchen, Two Systems of Buddhist Yoga

It is now in the present century, that for the first time, the West is finally beginning to learn something in depth about the ancient mystical teachings and practices of Buddhist Yogacara. Yogacara means to practice yoga, or in other words, to practice meditation, stilling the mind, searching inwards so as to acquire self-realization. This is the "practice tradition" at the heart of the Buddhist religion. Where ever Buddhism exists, there are those who commit themselves to this tradition - to the genuine "practice" of Yoga-meditation.

Here, the concept "practice" stands in contrast to "scholasticism". It means to practice a spiritual path, rather than study and debate philosophy. It means to practice yoga-meditation rather than trying to understand the meaning of life by using discursive reasoning.

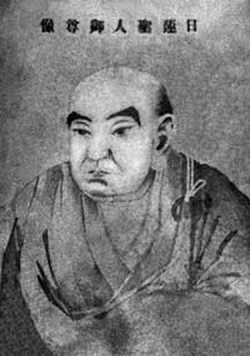

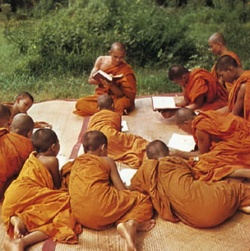

In Thailand and Burma, monks have for centuries taken themselves off to the forest, living simple ascetic lives, so as to devote themselves to contemplative practice. Likewise in Ceylon. Similarly, amongst Buddhists in China and Japan, we can see how various "practice tradition" movements have emerged in the form of what is now known as Ch'an meditation or Zen. An exemplar of the "practice tradition" in Tibet was the great yogi Milarepa, and it is from the latter that the Ka'gyu Order, now headed by His Holiness the Karmapa, descends to modern times.

Today, we follow the "practice tradition" of Buddhism than comes under the guidance of the 17th Gyalwa Karmapa, Urgyen Thinley Dorje. That is, we follow the tradition of yoga as taught in the Ka'gyu Order of Tibet.

By "practice tradition" we mean a tradition that is focused on the practice of spiritual conduct and meditation, where the individual aims to attain Enlightenment in his or her present life. Believing that the discursive intellect, on its own, is not capable of reasoning a way to true Enlightenment, the Yogin is a woman or man who turns to yoga-meditation so as to experience directly the nature of the mind.

Yogacara does not mean a particular set of views or religious beliefs. It does not imply a specific philosophy, such as the Middle Way View of Nagarjuna (Madhyamaka) or the Mind-only doctrine (Cittamatra), nor a system of thought like Vedanta or the scientific speculations of someone such as Stephen Hawkings. Though anyone may benefit from pondering the nature of existence and studying the thought of philosophy and science, and although we do study the above systems of thought, "Yogacara" strictly means to do meditation or various spiritual exercises that will lead to direct experience of the nature of the mind in and of itself. To know mind in the yogacarin sense is far more than a study of psychology—it means to directly experience one's own mind, fully and in all its aspects, including its deepest self-reflexive nature.

In Buddhist India and Tibet, the culmination of the long development of contemplative yoga practice led to two close systems of practice: the one known as "Mahasamdhi" or Dzogchen, and the other called Mahamudra. These are two branches of one original yoga system, introduced from India many centuries ago. Mahasamdhi means "absolute wholeness", or all-inclusive completeness. Mahamudra is a term referring to the "Great Seal" of nonduality. Both describe that final state of realization in which the duality of apparent existence, the differentiation of subject (consciousness) and object (world), collapses into original wholeness.

Dzogchen or Mahamudra is a "tantric" teaching concerning absolute Reality. In practice, this tradition says that absolute Reality (dharmata) can be known, but only through coming to experience the fundamental nature of one's mind. What is mind? Can we experience it?

We can perfectly well see that every sentient being has consciousness. We can see that consciousness is the perception of an object. There is no consciousness, without being conscious of something. What is consciousness conscious of? To guide the enquirer to an understanding of this question, it is pointed out that visual-consciousness is that which is conscious of visible phenomena. Through vibrations making an impression on the organ of sight, the eye, visual-consciousness is made aware of colour, light and form. The same goes for auditory-consciousness, tactile consciousness, and so forth. So "consciousness" is a state of mind that always is conscious of something. To recognize this, is to see that consciousness does not observe itself, because its very nature is to be preoccupied with observing something other than itself. At least this is apparently so.

Besides the actual five "sense-consciousnesses," associated with seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching, we can also speak of a mental-consciousness (mano-vijnana). Mental-consciousness is that which is aware of mental phenomena, such as our thoughts, feelings, desires and instinctual impulses, etc. When in Western psychology, and when in common western speech, we refer to the term "Consciousness", we are from a Buddhist perspective generally referring to the mano-vijnana. But we should take account of the other five consciousnesses as well. Indeed, we can assume that within the human brain there are thus six centres of consciousness.

But there are also, apparently, mental processes that go on, of which we are not conscious. In western psychology we say that these processes occur unconsciously, or subconsciously. Likewise, in Yogacara terminology, we speak of a process of mentation that is called the klista-manas, "obscured mind" or the "unconsciousness." A fundamental aim of Buddhist yoga practice is to remove this "obscuration" and bring to light this significant region of the human mind. The traditional yogi or yogini learns to penetrate into the unconsciousness (klista-manas) through the practice of one-pointed concentration and the nine stages of Shamatha meditation. Just as the darkness of a shadow vanishes before the light of a lamp, so it is said that the klista-manas exists not in the mind of the enlightened Arhat.

When the veil of the klista-manas is penetrated, the meditator experiences a vast new wealth of awareness. This deep and refreshing state of oceanic awareness is the unified field of consciousness (alaya-vijnana) of which each individual sentient being is, as it were, a finite spark. To experience unified mind is to gain a sense of communion with the very ground of existential consciousness in its own true nature. It is to know evolving "mind" (citta) in its fullest and most universal sense.

Nevertheless, to gain this experience, it has to be understood what mind or consciousness is. As emphasized above, we have to understand that "consciousness" (vijnana) is a mental function concerned with perceiving something other than "itself". This means that the world of experience is apparently divided into subject and object. To be conscious of an object, to "see" something, is to separate the consciousness which "sees" from the apparent object which is "seen." And this division of subject and object is a function inherent to consciousness itself. Thus, in a sense we might say, this is what makes "consciousness" what it is. Amazingly enough, if you think about it, this means that consciousness could not exist on its own, if no "object" were to exist. Thus subject and object are mutually interdependent.

To know mind in its own nature—to directly experience mind and arrive at awakened realization—the process of consciousness has to undergo a reversion in its very basis. This means that the continuous function of perceiving an object has to stop. The duality of observer and observed, of subject and object, has to collapse. In doing so, when there occurs a reversal of the basis in the depth of being, there then emerges an innate but previously not experienced, self-reflexive awareness (svasamvedana). For the yogin, this event comes as a stunning breakthrough. Strangely enough, however, nothing has actually changed-self-reflexive awareness is realized to have been there all along, from the very beginning. Recognizing this, we are made aware that self-reflexive awareness is precisely a unique state of knowing (jnana) innate to all intelligence. In other words, it is an absolute condition of intelligence "to know." "To know"-this IS what intelligence (vidya) actually is. Bare knowingness is nondual. It just is intelligence.

In the ancient Dzogchen Tantras, which for generations have been kept as actual "secret treatises" in the temple libraries of the yoginis and yogis of the Himalayas and in Tibet, it is revealed how, through meditation and insight, one may come to experience bare Intrinsic Intelligence, in its own essence. Indeed, the Dzogchen or Mahamudra system in particular, shows us that our own essential nature or "ultimate identity" is neither the body nor the consciousness, but rather, an immaculate and original Intelligence, which in the Tantras is described as being Param-adi-Buddha, the one supreme Absolute Intelligence itself. Original Intelligence-the very ground of all existence-is said to be entirely empty of ipseity; a self-luminous uncreate Clear Light of innate Knowingness, that is unlimited or unimpeded in the ever spontaneous manifestations of its endless love. The yogini and yogi who, through the methods of Mahamudra meditation, awakens to the intrinsic nature of mind, immediately realizes just this profound state of Absolute Totality (dzog-pa chen-po). To experience this is to make life meaningful. To experience this is to know that no one "disappears" when they die. It is to know the ultimate divine beauty of one's Essence. That knowing is perfect peace.

The purpose of the "Guru" (Tib: bLa-ma, the Master) in this Tradition is to point the spiritual seeker towards an immediate recognition of this "wholeness," which is our own root identity as bare Intelligence, and then to teach the yogacara methods concerning how to stabilize in one's consciousness, so that liberation may unfold naturally. The Master introduces one to one's own mind, by giving the pointing out instructions that describe what the actual nature of the mind is. The uniqueness of Dzogchen or Mahamudra is the rapid way in which meditation can lead to an experience of Enlightenment in this very lifetime.

An important step to understand the Mahamudra View is to distinguish between the nature of relative mind (citta) belonging to the worldly experience of consciousness and appearance, and that original uncreate state of bare, nondual Intelligence (known as Vidya), which is the essence or ground of what mind is, in and of itself.

The Master Shantideva, 7th century author of the Bodhicaryavatara, says:

"The absolute is beyond Consciousness; that which is within the realm of Consciousness is known to be always relative."

It is the all-inclusive Intelligence (vidya), empty of subject and object differentiation, that the Master attempts to point out to the seeker, and recognizing the meaning of that is what is called "acquiring the View of Absolute Wholeness." Mysterious as it may sound, this very recognition allows mind to undergo the fundamental reversion of its basis, so basic for realization, whereby mind's inherent nature becomes revealed nakedly. Abiding in a state of attention, which merely holds to the View, without falling into linear thinking, forgetfulness or distraction, is the meditation. Sustaining that calm abiding state allows natural evolution to unfold into eventual Liberation.

As the great yogi-master Patrul Rinpoche used to say:

"The essence of mind, the very face of Intelligence, is introduced [to the seeker] at the very instant that conceptual consciousness is let go of."

To approach the teachings of Mahamudra there are certain preliminary meditation practices. One of our great teachers, the late Kyabje Dilgo Khyentse Rimpoche, emphasized the importance of these preliminaries (Ngön-dro) when he said:

"Without the preliminaries, or foundation practices, the main practice [of meditation) will not resist deluded thoughts, and carried away by circumstances the mind will be unstable."

Therefore those who come to the Dharma Fellowship seeking instruction in Mahamudra, are introduced to the teachings in a step-by-step process. They must begin with the preliminaries, the Purvaka Exercises, so as to lead them into the profound methods of Buddhist Yoga safely and carefully.

As the seeker becomes more confident in performing meditation, and as a spiritual foundation is laid, he or she may then be introduced to the Tantric yoga methods of our school. With time, the Four Transmissions of Tilopa are explained - consisting of Chandali-yoga (or what is sometimes called, Kundalini), the Illusory-body meditation, Clear Light, and Karmamudra practices. Such a spiritual path, with its attendant exercises, leads deep into the heart of Mahamudra. Then rapid unfoldment can happen in earnest.

This is meant to be a very brief outline of what Dzogchen or the Mahamudra Yogacara way is all about. Forgive us if we have left much out, or been less than clear in trying to explain this most difficult to describe, profound Path of Nondualist Mysticism.

09 Apr `09, 10:26AM

Cog

Here's an article (among a number of others), which I think are quite well written, shared to me by a friend 'mikaelz':

I had a wonderful meeting with Harada Roshi for one hour at Sogenji in Okayama on Monday. I managed to digitally record the discussion and have it

now on my computer to listen to. Harada Roshi was very gracious and answered all my Dharma questions regarding Zen practice, Ki and how total Awareness as the essential

Buddha Nature comes about.

He also gave me much advice regarding my training others in Zen and offered to give me advice as I may request in the future. He confirmed everything we have been discussing in recent months as being exactly the way one would describe it from the experience of Zen Mind or

Satori, and asked why would one think that the experience could be different than the Tibetan traditions?

I really felt I was sitting with a fully enlightened Buddha, a lineage holder of that tradition going back to the original experience that Gautama Buddha shared with the world over 2500 years ago. I will go into his essential instructions over the next couple of days. But essentially

his view was extremely clear and left no wiggle room for doubt in one's practice. Let me relate Julie and Brett's recent conversations on Awareness and how to work with skillful means such as the rushen of Dzogchen to Harada Roshi's comments to me.

When we are speaking of some sort of practice to open up the space of Self-realization, we are already lost in duality and conceptualization and are essentially making matters worse. This is enabling the assumption that there is some state that is attainable if one could just get the practices and subsequent insights "just right". We have objectified Awareness or Rigpa as some sort of state that comes and goes... in glimpses that grow and stabilize with more and more familiarity over time. But we must come to see that the reverse is true: Rigpa or Awareness

is always stable and fully present, it is the energy of conceptualizing mind that comes and goes like waves on the sea. Otherwise we remain snared in a subtle state of ego-mind that is always chasing some experience called Awareness. Awareness cannot be attained through practice. It is only when ALL efforts at getting somewhere beneficial with our practice dissolve that it is discovered that what is being looked for is exactly one's awareness in this moment...not some future moment. This concept that there is some other "higher" Awareness that will result after one gets it just "right" is delusion and should be made clear. The essential requirement is that the ego-self mind projection must dissolve totally for all of this to become self-evident, suddenly. Since that mind projection arises freshly from moment to moment, there is always a gap where that ego-self is already non-existent. When that ego-self is absent only Awareness shines, and in that moment of Self-Knowing, it is recognized that there is no one who needs to attain enlightenment, as the present Awareness is unchanging Enlightenment Itself.

This is a direct experience.. . that occurs to no one... but does occur. Practicing being aware of Awareness does produce some pleasant experiences of openness and clarity for sure.

But we are still "doing" something from the viewpoint of ego as ego. Then the ego tries to re-experience those positive states again and again in the vain hope it will gain greater and greater stability in this state that is now being labelled "Rigpa" or Awareness by the ego consciousness. It gets very tricky here... we have to be very alert to what is arising disguised as whatever it seems to be.

Again secondary practices are resorted to only when this initial" pointing out" or "direct introduction" have failed. Let's not give in so easily to the ego's needs and desires to be able

to "do something" to bring things along a bit according to its samsaric view of its situation. All

doing, study and effort is exerted by one's ego, one's Awareness has no need of any such activities in order to be what it already is and has always been. Awareness has not forgotten who and what it truly is and now needs to remedy the situation! There is no situation that needs remedying, but there is a conceptual belief that there is. That conceptual belief is just as invalid as the belief that there is an individual being or person, and stems directly from that conceptual ignorance. All of these concepts and feelings are arising within your Awareness as the

one who is having the experience.. . but it is being experienced from a place where no concepts of self, nor problematic situations exist. These delusions of being a self and its distractions just arise without any benefit or harm to the experiencing Awareness.

Entering the Way directly is extremely easy and pleasant. Your sensory perceptual faculties are not a product of ego-consciousness. The ego does not create the ability to see, hear, feel, taste or smell. Just seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting and smelling immediately and directly are the functions of the Buddha Nature. However, thinking and conceptualizing about those direct and immediate perceptions is where and how ego consciousness enters the stage... always after the fact. First moment of direct perception is the Buddha Mind functioning. The immediate next moment the sensory perceptions are processed through ego consciousness. Naked perceiving, free of all conceptualizing through the five senses is being a Buddha in all that you do.

There is the wisdom of the Buddha Nature)] that directs one's actions with out need of conceptualizing.

Freedom is living fully in the moment of now, by taking everything that arises "as it is" and leaving it as it is. Whatever perceptions arise leave them just as they are. Whatever internal events, such as thoughts and feelings arise, leave them just as they are. But if you now conceptualize that as "ok, I will just leave things exactly as they arise as my practice", you have already committed a fatal error as the ego has now turned this into its own believed method of practice that will lead

to some enlightened or higher state or so it hopes!

Just hear a sound... hear the next sound. Is there any separation between the sound, the hearing and your Awareness of it? Is the sound heard and your Awareness of it inseparable at that moment? Is that immediate and non-dual samadhi where the unified field of Awareness and

Energy are in seamless Oneness? That being the case... how can you say the realization of Oneness is difficult or requires effort and practice to attain? It occurs with every sound heard...

When you are Aware of any experience.. . internal or external perceptions, aren't you Aware of each and every one of those experiences that you have knowingly experienced? If

so, how can you say that it is difficult or that it requires effort and practice in order to find true Awareness, the default knowing and perceiving Awareness of the Buddha Nature that is having those experiences?

Your Buddha Awareness is alive and well in each moment already... who

do you think is reading this?

Indeed, Awareness cannot be reached through development. It cannot be cultivated. It cannot be attained. It cannot be fabricated through contrived practices. It cannot be an event in time since it is Prior to time.

It is present before you were born, present 1 year ago, 1 minute ago, present now. Unmoved.

It is unconditioned, does not increase upon enlightenment nor decrease while ignorant, nor disappear at any time, regardless of whatever conditions there is.

It is not an experience that comes and goes but the ground of all experiencing. But it is at the same time one with all experiences, all transience.

As Kennethfolk said: Development doesn't lead to Awakeness; Awakeness is always already here. The fact that we insist upon not noticing it is another matter.

And that is what pointing out instructions do -- just so you notice your ever present awakeness.

Yet it is unlikely that a person will have full conviction in that upon the first pointing out. It usually takes years of practice and the right conditions. Sometimes the teacher only gives the pointing out after he sees the conditions are ripe.

http://www.wheniawoke.com/Titles/pointing-out2.html

Here is a historical example dialog from the Dzogchen tradition. The following occurred in Tibet a long time ago. (Reprinted from Dzogchen & Padmasambhava by Sogyal Rinpoche). Nyoshul Lungtok was a very great Dzogchen master, who followed his teacher Patrul Rinpoche for about eighteen years. Nyoshul Lungtok would keep telling Patrul Rinpoche that he had not yet got the main point, of realizing Rigpa. Maybe he had, but he really wanted to be sure, so he kept on asking him. Then Patrul Rinpoche gave him the introduction. It happened one evening whilst Patrul Rinpoche was staying up in one of the retreat centers above the Dzogchen monastery. It was a beautiful night; the sky was clear, and the stars were very bright. It was very quiet, and the sound of solitude was heightened by the distant barking of a dog from the monastery below.

Nyoshui Lungtok had not asked him anything that evening, and Patrul Rinpoche called him over, saying "Didn't you tell me that you still hadn't got the main point of the practice of Dzogchen?" Nyoshul Lungtok replied: "Yes, that's right".

"It's very simple", he said, and lying down on the ground, he beckoned to him: "My son, come and lie down here like your father" So Nyoshul Lungtok did so. Then Patrul Rinpoche asked him, in a very affectionate way: "Do you see the stars in the sky?"

"Yes"

"Do you hear the dogs barking from the Dzogchen monastery?"

"Yes"

"Do you hear what I am saying to you?"

"Yes"

"Well, the nature of Dzogpachenpo is just - simply this."

At this moment, everything fell into place, and instantaneously Nyoshul Lungtok was completely realized.

To reach enlightenment, we need to remove forever two sets of obscurations:

emotional obscurations (nyon-sgrib) – those that are disturbing emotions and attitudes and which prevent liberation,

cognitive obscurations (shes-sgrib) -- those regarding all knowable and which prevent omniscience.

These obscurations bring us, respectively, the suffering of uncontrollably recurring existence (samsara) and the inability to be of best help to others. They are fleeting (glo-bur), however, and merely obscure the essential nature (ngo-bo) of the mind and limit its functioning. In essence, the mind (mental activity) is naturally pure of all fleeting stains. This is an important aspect of its Buddha-nature.

[See: Ridding Oneself of the Two Sets of Obscurations in Sutra and Anuttarayoga Tantra According to Nyingma and Sakya.]

In general, to remove both sets of obscuration requires bodhichitta (byang-sems) and nonconceptual cognition of voidness (stong-nyid, Skt. shunyata, emptiness) – the mind’s natural absence of fleeting stains and its absence of impossible ways of existing (such as inherently tainted with stains). Bodhichitta is a mind and heart aimed at enlightenment, with the intention to attain it and thereby to benefit all beings as much as is possible. Removing obscuration also requires a level of mind (or mental activity) most conducive for bringing about this removal. Dzogchen practice brings us to that level.

Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche

Interview for Vajradhatu Sun, 1985

The following interview with Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche was recorded on the 16th day of December, 1985, at Nagi Gompa, outside of Kathmandu.

When Rinpoche was asked if he would grant an interview for the Vajradhatu Sun, his reply was, "What is the use of the tiny light of a firefly when the sun has already risen in the sky?" referring to Trungpa Rinpoche's presence in the West.

Q: Can Rinpoche please tell us about his life, his teachers, and the retreats he has done?

R: I was born in Eastern Tibet, in Kham, in the area called Nangchen. The Dharma teaching of my family line is called Barom Kagyu. My grandmother was the daughter of Chokgyur Lingpa, the great terton, so my family line also practices the Nyingma teachings. Since I hold the lineages of both Kagyu and Nyingma, my monastery in Boudhanath is therefore called Ka-Nying Shedrub Ling, The Kagyu and Nyingma Place for Teaching and Practice.

From the time I was quite small until the age of twenty-one, I stayed with my father who was a Vajrayana teacher and tantric layman. His name was Tsangsar Chimey Dorje. My father was my first teacher and from him I received the transmission for the Kangyur, the entire teachings of the Buddha, and also for the Chokling Tersar, "The New Treasures of Chokgyur Lingpa." Later, I studied with my father's older brother, Tulku Samten Gyatso from whom I received also, among other things, the entire transmission of the Chokling Tersar.

Later on I studied with an incredible great master named Kyungtrul Karjam and from him I received the entire Dam-ngak Dzo as well as Chowang Gyatsa, the Hundred Empowerments of Cutting Practice. He also passed on to me the reading transmission for the Hundred Thousand Nyingma Tantras and the Jangter Gongpa Sangtal, the Northern Treasure of Unimpeded Wisdom Mind. In particular, I received from him a detailed commentary and clarification of the important treasure of Chokgyur Lingpa renowned as Lamrim Yeshe Nyingpo, the Gradual Path of The Wisdom Essence.

From the time I was eight years old, I received teachings on the nature of mind from my own father, and I was lucky later on, to receive detailed instructions in the form of "guidance through personal experience" from Samten Gyatso on the teachings of Dzogchen, the Great Perfection. From my other uncle, Tersey Rinpoche, who was a close disciple of the great siddha Shakya Shri, I was also lucky to receive teachings on Dzogchen.

Moreover, I again received detailed teachings on Lamrim Yeshe Nyingpo from Jokyab Rinpoche, a disciple of Dru Jamyang Drakpa. The body of teachings known as Rinchen Terdzo, the Precious Treasury, I received from Jamgon Kongtrul, the son of the 15th Karmapa. As for the other of the Five Treasuries, I received the Gyachen Kadzo from my third uncle, Sang-ngak Rinpoche, the Kagyu Ngakdzo from H.H. the 16th Karmapa himself, and the Sheja Kunkyab Treasury from Tana Pemba Rinpoche. I addition, I have received the root empowerments of Jigmey Lingpa from H.H. Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche several times.

In Eastern Tibet I spent three years in retreat just reciting the Mani. [Laughs]. Later on at Tsurphu, the seat of the Karmapas, I also spent three years in retreat and then again in Sikkim I was able to spend almost three years in intensive practice. Lately, I have been here at Nagi Gompa for a few years. That's my life story.

Q: What lineages does Rinpoche hold?

R: My family line is the holder of the Barom Kagyu teachings which originate from Gampopa's disciple Barom Dharma Wangchuk. His disciple was Tishi Repa whose disciple was called Repa Karpo. His disciple again was Tsangsar Lumey Dorje. His disciple, Jangchub Shonnu of Tsangsar, is in my paternal ancestral lineage. The line of his son and his son again, all the way down to my father, is called Tsangsar Lhai Dung-gyu, the Divine Bloodline of Tsangsar.

My incarnation line is called Chowang Tulku. With that same name I am just the second. My past life was said to be an incarnation of Guru Chowang. He was also said to be an emanation of one of the twenty-five disciples of Padmasambhava called Nubchen Sangye Yeshe, but who knows that for sure. [Laughs]. My former life, Chowang Tulku, was a "secret yogi." No one knew how his practice was, but when he passed away his body shrunk down to the size of one cubit without decomposing.

Q: What does Dzogchen mean?

R: Dzog, "perfection" or "completion," means as in this quote from a tantra, "Complete in one - everything is complete within mind. Complete in two - everything of samsara and nirvana is complete within this."

"Dzog" means that all the teachings, all phenomena, is completely contained in the vehicle of Dzogchen; all the lower vehicles are included within Dzogchen. "Chen," "great," means that there is no method or means higher than this vehicle.

Q: What is the basic outline of practice according to the Dzogchen path?

R: All the Buddha's teachings are contained within nine gradual vehicle of which Dzogchen, the Great Perfection, is like the highest golden ornament on a rooftop spire, or the victory banner on the summit of a great building. All the eight lower vehicles are contained within the ninth which is called Dzogchen in Tibetan, Mahasandhi in Sanskrit [and the Great Perfection in English]. But Dzogchen is not contained in the lowest one, the shravaka vehicle. So when we say "perfect" or "complete" it means that all the lower yanas are perfected or completely contained within the Great Perfection, within Dzogchen.

Usually we say that Dzogchen, sometimes called Ati Yoga, is a Dharma tradition but actually it is just the state of one's mind, basically.

When it comes to combining these following two points into actual experience, we can use the statement of the 3rd Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje, "It is not existent as even the buddhas have not seen it." This means that the basic state of mind is not something that exists in a concrete way; even the buddhas of the three times have never perceived it. "It is not non-existent as it is the basis for both samsara and nirvana. This is not a contradiction, it is the middle path of unity." Contradiction is like having fire and water on the same plate. Its impossible. But that is not the case here. The basic nature is neither existent nor non-existent - these two are an indivisible unity. "May I perceive the mind nature free from extremes." Usually when we say "is" it contradicts "is not." And when we say "non-existent" it contradicts "existent." But this middle path of unity is devoid of such contradiction. When it is said "to attain the unified state of Vajradhara," that actually refers to what I discussed here.

This unity of being empty and cognizant is the state of mind of all sentient beings. There is nothing special about that. A practitioner should encompass that with "a core of awareness." That is the path of practice. Again, "the unity of being empty and cognizant with a core of awareness."

The special feature of Dzogchen is as follows: "Primordial pure essence is Trekcho, Cutting Through." This view is actually present in all the nine vehicles, but the special quality of Dzogchen is what is called "The spontaneously present nature is Togal, Direct Crossing." The unity of these two, Cutting Through and Direct Crossing, Trekcho and Togal, is the special or unique teaching of Dzogchen. That is how Dzogchen basically is. That's it.

Q: That is a very wonderful teaching. It seems like Dzogchen is very direct and doesn't seem to have a linear quality in terms of the way one would approach it. In the other yanas sometimes one would first do the set of preliminaries, then a yidam practice. tsa-lung practice etc., this and that. It seems like Dzogchen is very immediate, like the essence is already present, available. Is there any kind of linear path in the way one would approach these teachings or is it always direct, like this?

R: We do in the Dzogchen tradition have the gradual system of preliminaries, main part and so forth. But the special characteristic of Dzogchen is to introduce or point out directly the naked awareness, the self-existing wakefulness. This is for student who are suitable, meaning those who have sharp mental faculties. In stead of going through a lot of beating around the bush, one would introduce them directly to their mind essence, to their self-existing awareness.

Dzogchen is said to have great advantage but also great danger. Why is this? Because all the teachings are ultimately and finally resolved within the system of Dzogchen. This can be divided into two parts, resolving all the teaching through intellectual understanding and through experience.

To resolve through experience is what is the great advantage or benefit in the sense that having pointed out and recognizing directly naked awareness and simply makes that the main part of practice. That is the point when there is an incredible great benefit because that itself is the very direct and swift path to enlightenment.

On the other hand, the great danger is when one just leaves it as intellectual understanding, that "In Dzogchen there is nothing to meditate upon. There is nothing to view. There is nothing to carry out as an action." That becomes just a concept of nihilism and is completely detrimental to progress. This is because the final point of the teaching is conceptlessness, being beyond intellectual thinking. Yet, what has happened is that one has created an intellectual idea of what Dzogchen is and holds on to that idea very tightly. This is a major mistake that can happen. So, it is very important to take the teachings into one's personal experience through the oral instructions of one's teacher. Otherwise, simply to have the idea "I am meditating on Dzogchen" is to completely miss the point.

Self-existing wakefulness is present within the mind-stream of all sentient beings since primordial time. This presence is something which should not be left as theory, but should be acknowledged though one's experience. One first recognizes it, then trains and attain stability in it. That is when it is said that Dzogchen has great benefit. There is actually no greater benefit than this.

Great danger means that when this is left as words of mere intellectual understanding then one doesn't gain any experience but merely holds some concept about it and lack the nonconceptual quality. Conceptual mind is merely intellect whereas experience to remain in the continuity of naked awareness; growing used to it what is called "experiencing."

It is the same principle whether one talks of Madhyamika, Mahamudra or Dzogchen. As is said in the Bodhicharya Avatara, "When one's intellect holds neither the concept of concreteness nor of inconcreteness, that is the state of not conceptualizing." As long as one is not free from concepts, one's view remains as mere intellectual understanding and the Dzogchen view is then left as mere theory. One might then think "Dzogchen is primordially empty, it is free from a basis. There is nothing to meditate upon, no need to do anything If I meditate in the morning, I am a buddha in the morning. When I recognize at night, I am a buddha at night. The destined one does not even have to meditate."

Actually, Dzogchen is the way to purify the most subtle obscuration of dualistic knowledge - it is something quite in credible. But if one only imagines it, if it is a mere theory, thinking "I don't need to do anything, neither meditate nor practice," [one's has completely missed the point]. There has been many people thinking like this in the past.

Compared to straying into an intellectualized version of Dzogchen, it is much more beneficial to practice according to Madhyamika or Mahamudra where one goes along step by step, alternating theory and experience within the structure of theory, experience and realization. Proceeding gradually in this way one becomes more and more clear about what is to be resolved and then finally captures the "dharmakaya throne of nonmeditation." In this graduated system there are some reference points along the various paths and levels. But in Dzogchen the master will from the very beginning point out the nonconceptual state, instructing the student to remain free from concepts. It then happens that some student will think, "I am free from concepts, I am never distracted!" while walking around with vacantly gazing eyes. That is called straying into intellectual understanding.

Later on, when we have to die, mere theory will not help us whatsoever. Tilopa told Naropa, "Theory is like a patch. It will wear and fall off." After dying, we will undergo various pleasant and unpleasant experiences, intense panic, fear and terror. Intellectual understanding will not be able to destroy those fears; it cannot make confusion subside. So, merely to generalize that one's essence is devoid of confusion is useless. It's only a thought, another concept, which is ineffective at the moment of death when it comes to deal with one's confusion.

Q: What will help then?

R: One needs to recognize the view of one's essence. If one hasn't thoroughly acknowledged the correct view but only constructed it from concepts, this intellectual understanding will be useless. Its like knowing that there is a delicious meal to be eaten. Without putting it into one's mouth one will never know what is tastes like. Likewise, one needs to be totally free from the merest flicker of doubt concerning the state of naked awareness. Jigmey Lingpa said about having stability in awareness, "At this point there is no need for 100 panditas and their thousands of explanations. One will know what is sufficient. Even when questioned by these scholars, one will not give rise to doubt. So the main point is to be stable in awareness through experience.

This awareness is not introduced through an intellectual understanding where one only has the idea of it. When a qualified master encounters a worthy student it is like iron striking flint creating fire immediately. When such two persons meet together it's possible to be free from doubt.

When one doesn't feel any doubt, no matter how much one may try, that is the proof of having recognized the mind essence. But if it's possible to start doubting, thinking "I wonder how it is, what shall I do?" that is the proof of having mere intellectual understanding.

This difference between theory and experience is what I basically meant by saying that Dzogchen has both great benefit and great danger.

When a practitioner is introduced to naked awareness he will be able to attain enlightenment in that very body and lifetime because in the moment of recognizing the essence of awareness, the obscuration of dualistic knowledge is absent. This is called "touching the fruition." In this respect there are three ways: taking ground as path, taking path as path, and taking fruition as path. Receiving the pointing-out instruction means that one takes fruition as path. That is why it is so precious. So don't let it stray into mere theory.

Experience is said to be the "adornment of awareness." Awareness is present within all beings; whoever has mind has awareness since it is the mind's essence. The relationship between mind and awareness is mind being like the shadow of one's hand and awareness being the hand itself. In this way, there is not one single sentient being who does not have awareness. We might hear about awareness and then think "I understand, awareness is just such and such." This mental construct is totally useless - from the very first the absence of mental fabrication is crucial. As is said, "Within the naked dharmadhatu of non- fabrication."

Introducing awareness means to point out the absence of mental fabrication. Otherwise it becomes an introduction to mere discursive thought. [Laughs]

Q: What is the difference between the practice of Dzogchen and that of the Anuttara Yoga Tantra in the system of the New Schools, (sarma) (gsar ma) It was taught that all the eight lower vehicles are contained within Dzogchen, so how does the difference come about?

R: In the system of the New Schools, there are first of all the four tantras of Kriya Tantra, Charya Tantra, Yoga Tantra, and Anuttara Yoga Tantra. The fourth is divided into Father Anuttara Tantra, Mother Anuttara Tantra and Nondual Anuttara Tantra. This correspond exactly to the structure of the Old School, Nyingma, in that father tantra of Anuttara is Mahayoga, mother tantra is Anu yoga and the nondual tantra is Ati Yoga, (Dzogchen). However, there are no explicit teachings on Togal in Anuttara. That is the main difference, whereas it is taught that there is no difference whatsoever between "essence Mahamudra" and Dzogchen in meaning - only in terminology.

Concerning the inclusion of the lower vehicles in the highest is "All phenomena of samsara and nirvana are included with the expanse of awareness." That is the meaning of "inclusion."

Q: There are many kinds of conceptual practices in Anuttara Yoga such as visualization and manipulations of the nadis and pranas. How do the fit into the Dzogchen system?

R: These practices actually belong to the systems of Mahayoga and Anu yoga. However, in Ati Yoga which should be effortless, free from fixation, these practices are applied as "means for enhancement." Q: From where does the tradition of giving the transmission of the pointing-out instruction originate?

R: The first origin is what we call the "mind transmission of the victorious ones." After that there was the "sign transmission of vidyadharas" and today we have the "oral transmission of great masters." First, the mind transmission of the victorious ones, was when the manifestation aspect of Samantabhadra appeared in a bodily form and the five families of victorious ones recognized dharmata by merely seeing this bodily form. This was mind transmission through simply manifesting as a deity without the need for any conversation. This mind transmission seems to have gradually degenerated. Following that, by means of the sign transmission of vidyadharas such masters as Garab Dorje, Shri Singha and Guru Rinpoche recognized the self-existing wakefulness of dharmata through a simply gesture such as a finger pointing at the sky. Finally, Guru Rinpoche, The Eight Indian Vidyadharas as well as the Tibetan King, Subject and Companion (Trisong Deutsen, Vairotsana and Yeshe Tsogyal) and so forth gave teachings through oral transmission. This oral transmission which comes from India and is not a Tibetan invention, was originally imparted by whispering through a copper tube such as in the case of Vairotsana into whose ear was whispered the sentence, "The single sphere of dharmakaya, self-existing wakefulness, inconceivable reality, is present within the mind of sentient beings. Oral transmission literally means "transmitted into the ear."

In the case of the Kagyu lineage, Tilopa stated, "I have no human masters. My master is Vajradhara himself." Marpa Chokyi Lodro So, figuratively speaking, Vajradhara gave the teachings to Tilopa and Tilopa transmitted them orally to Naropa who then passed then on to Marpa. He gave them to Milarepa and he again to Gampopa from whom they were orally transmitted to the "four great and eight lesser lineages.

In the case of the Nyingma lineage, Guru Rinpoche, Vimalamitra and Vairotsana passed the teachings on chiefly as an oral transmission to the Twenty-five Disciples headed by the King, Subject and Companion. Here Dzogchen was transmitted as the pointing-out of the expression of awareness; not to awareness itself but to its expression which is dharmata. From this point, the Twenty-five Disciples passed the teaching on to the Eighty Tibetan Siddhas and others such as the various oral lineages as well as the treasure lineages, so that this transmission has been uninterrupted down until our own root guru. If the lineage had been broken there would be no pointing-out and recognition

of awareness.

Q: Why is this pointing-out instruction considered so important?

R: That is self-evident. Isn't awareness the actual path for attaining enlightenment? There is nothing more important than recognizing it and become a buddha [laughs]. If you put all the riches in the world on one side and the pointing out of awareness on the other, awareness will be more valuable for enlightenment.

Q: Having received the pointing-out instruction and recognized, will that itself be sufficient or how should one train?

R: Once one has received the pointing-out instruction there is the chance of either recognizing it or not. But a student who has actually recognized will have enough for this entire lifetime in the "single sufficient instruction." The same goes for the bardo state. Yet, one can still apply the paths of Mahayoga and Anu yoga for enhancement and for clearing away hindrances. Once one has recognized one's essence, it is like a fire that only will blaze up more intensely the more firewood is added; the fire will never diminish with the adding of wood. Similarly, there will be benefit from applying the paths of Mahayoga and Anu yoga; even Hinayana practice will be beneficial.

According to one's ability one can apply what one feels inclined towards - like gathering honey from many different flowers. Or, simply to cultivate and practice the recognition of awareness alone will be sufficient for attaining enlightenment within this body and lifetime. All the different practices of Mahayoga and Anu yoga, as in the system of Jamgon Kongtrul the First, are for the purpose of attaining stability in awareness. While benefiting beings one can become more stable in awareness. As I already mentioned, fire blazes up and increases the more wood is added; it is not the opposite way.

Having recognized one's essence, one should sustain its continuity. There will be no benefit from simply leaving it with "I have recognized!" It is necessary to maintain the continuity of awareness until all confusion and conceptual thinking has been exhausted. That itself is the measure; when thoughts are exhausted then it is enough. There is no more need for meditation or for "sustaining the continuity."

Q: Although Rinpoche has a large monastery in Boudhanath, Kathmandu, I notice that he spends most of his time up at Nagi Gompa Retreat Center. Why is that?

R: As a matter of fact, it is said, "In this age of degeneration, carry the burden of the Doctrine. If you are not able to do so, simply the fear that the teachings will die out occurring in your mind for but instant will have tremendous merit." For this reason, the purpose of building a monastery with a gathering of the sangha of monks - as just an image of the doctrine in this dark age - is that we have the great hope that they will practice the tradition of the Dharma. Whether or not the monks individually do any practice is their own business.

But if they just wear the robes on their bodies, cut the hairs on their heads and gather together in a group of merely four monks, the benefit of accumulating merit and purifying one's obscurations will result from the respect, faith and donations one can make as a benefactor, no matter how insignificant one's contribution or faith may be. This is independent of whether or not the monks misbehave or misappropriate their donations; that is totally up to themselves. For the benefactors, their will be the blessings of the Buddha when they make a donation to a gathering of just four monks. Their will be no failure in that for the patrons themselves. It is for this reason that I took the effort to build a monastery. Moreover, this age is the time when Buddhism is slowly dying out, like the sun about to depart while setting over the mountains in the west. Considering this combined with having received the command of His Holiness Gyalwa Karmapa, we have constructed this insignificant monastery.

The place up a Nagi Gompa was initially build by the meditator and hermit Kharsha Rinpoche as a hermitage for his following of monks and nuns. After he passed away, the place was offered to Karmapa who then placed me as a caretaker. So I, this old man here, is just a caretaker [laughs]. That is the only reason why I live up here; I am not at all like Milarepa, living in mountain retreats and caves after renouncing samsara. But I have a nice spot to sleep on and a warm place in the sun [laughs]. That is how I live.

Q: What is the benefit and purpose of doing retreat practice?

R: With many distractions one is not able to practice the Dharma properly. Distraction means a lot of business, noise and things to do. When going up in the mountains there will be less distraction. That is the reason for mountain retreat. In addition to that, if one is able to keep some discipline, remaining in solitude without allowing outsiders to visit and not going out oneself, there will be no other distraction than that made by one's own mind. External distractions have been eliminated. That is the purpose of seclusion.

When distractions have been abandoned one can exert oneself in the practice. Through exertion it is possible to destroy confusion. When confusion falls away, enlightenment is attained. That is the whole reason [laughs].

Q: Finally but not least, does Rinpoche have any special advice for the readers of Vajradhatu Sun who are primarily householders?

R: They should first of all receive the pointing-out instruction and recognize their essence. Having recognized, they should refrain from losing its continuity and then mingle that with their daily activities. There are basically four kinds of daily actions traditionally called moving, sitting, eating and lying down. We don't always only sit or only move about; we alternate between the two. In addition we eat, shit and sleep. So there actually seem to be five kinds [laughs]. But at all times, in all situations, one should try not to lose the continuity of the practice. One should try to be able to mingle the practice with daily life. As one gets more accustomed, any amount of daily life activities will only cause nondualistic awareness to develop and become the adornment of this undistracted awareness, free from being obscured or cleared.

When one is able to mingle practice with the activities of daily life, these activities will then be beneficial and devoid of any harm whatsoever. That is if one has already recognized one's essence correctly. Without the correct recognition one will get carried away by the daily activities - one will have no stability. Lacking stability is like a strand of hair in the wind bending according to how the wind blows whereas a needle will be stable no matter how small it is. Even a very thin needle cannot be bent by the wind. Once one has truly recognized one's essence one cannot be carried away by the activities of daily life, just as a needle that is stable. Dualistic mind is completely unstable, like a hair that is just ready to move by the tiniest breeze; it falls prey to the five external sense objects. Awareness, on the other hand, when properly recognized, does never fall subject to sense objects. It is like a needle that is unmoved by the wind.

—Translated by Erik Pema Kunsang. © Rangjung Yeshe Translations & Publications,