Tantric activity in practice

Although the subject area of this book is the Renaissance as a whole, it will focus on key factors in the process of building stable social and political institutions in general and Sakyapa systems in particular. It so happened, but the variants of esoteric Buddhism practiced by the Sakyapa attract much more attention than other no less interesting and no less significant developments.

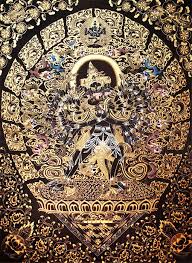

This seems to be an unfortunate limitation, but it is due to the wealth of available material associated with this school, as well as its vigorous activity during this period, which had a huge impact on the final alignment of the political-religious forces of Tibet. This emphasis is particularly relevant in part of its doctrinal system, which was studied by Kublai himself after his initiation into the Hevajra mandala in 1263.

The chronicles of this meditation program, known in Tibet as the lamdre or "the path and its fruit", are the subject of a monograph by Cyrus Stearns. However, his scientific work uses a methodology based primarily on the approaches of the tradition itself28. Therefore, such integral attributes of critical historiography as social factors, ideological imperatives and the accompanying religious framework still need to be considered more carefully29.

Sometimes referred to as the “pearl” of Sakya tantric practice, the lamdre allegedly appeared in Tibet in the 1040s through the efforts of one of the most eccentric characters in the history of Indian Buddhism, Kayastha Gayadhara. It is believed that in Tibet Gayadhara met a highly educated, but at the same time greedy Drokmi Lotsava, with whom he worked on various translations for five fruitful years.

Unfortunately, there are some doubts about the reputation of Gayadhara, and therefore research should be done on the possible Indian predecessors of the lamdre, and the whole system should be placed in the context of interaction between Tibetan religious circles and their neighbors. This book claims that the lamdre has become much more than what Gayadhara is said to have created.

The lamdre is not just a sequence of complex inner yogic meditations, it has also become a symbol of the growing power and authority of the Khon clan in south-central Tibet. Along with other esoteric traditions used in the Sakya, the lamdre embodied the Khon's claims to uniqueness and allowed the Khons to establish themselves as one of the most significant carriers of the aristocratic culture of this medieval pre-Mongol period.

This book consists of nine chapters and a conclusion. Chapter 1 explores the origins of Indian esoteric Buddhism in the ninth and tenth centuries. Based on my previous work* on this period,30 it summarizes the socio-political and religious conditions of early medieval India and examines the tantric developments of those times. This chapter also presents early versions of the legends of the Indian siddhas Naropa and Virupa, as they were the two most important siddhas for renaissance Tibetans.

——————————————————————-

- See the Russian translation of this book "Indian Esoteric Buddhism: A Social History of the Tantric Movement"

Chapter 2 examines the political and social situation that developed in Tibet in connection with the fall of the monarchical dynasty of the Yarlung rulers, as well as the position of Ralpachan, his assassination and the usurpation of the throne by his brothers.

The chapter then describes the collapse of the empire due to a succession dispute between the surviving factions of the crown princes and its consequences for Tibet's state structures and clan system. Tibet's slide into social disorder and the three uprisings are discussed at some length, as well as the situation of religion as it looked at the end of the dark times of the fragmentation period.

Chapter 3 looks at the revival of Buddhism in Central Tibet in the late tenth and early eleventh centuries. We examine the extraordinary activity of the first "U-Tsang people" in order to show that the growth of the temple network of Central Tibet was an important prerequisite for the transition to the era of great translators.

This chapter focuses on this network and examines the conflicts between its monks and the Bende, along with other quasi-monks. Furthermore, we are discussing here the expected spread of the Kadampa, whose famous founder Atisha only arrived in Central Tibet around 1046, i.e. many decades after the beginning of the restoration of monastic Buddhism from the Sino-Tibetan border.

Chapter 4 focuses on the later translators and discusses their position as intermediaries between Tibet and South Asia. At the same time, we explore the motives and methods of translation of the Indians, which they used in the process of creating texts in Tibet. The legitimacy of the translators' lineages is also analyzed, mainly using the classic example of a hagiographic story with fictitious Marpa's heirs. It also discusses the confrontation between translators and representatives of the old imperial dynastic religious systems (by that time already called "ancient" [[[nyingma]]]). Finally, we show how the individuals and groups of the eleventh century were fascinated by the emerging cult of learning and mystical knowledge.

Chapter 5 addresses the figure of Drokmi, one of the first esoteric translators of Central Tibet and a very extraordinary personality. We analyze his travels to Nepal and India, as well as his meeting with Gayadhara, an eccentric and somewhat dubious Bengali saint. In this case, we study the activities of Drokmi based on the translation and analysis of the earliest work on him by Drakpa Gyaltsen (1148–1216).

It also discusses the Drokmi community in the Mugulung cave dwelling, the prehistory of Gayadhara, and Drokmi's literary heritage, and summarizes the lamdre root text and the "eight auxiliary cycles of practice." Finally, we examine Drokmi's translation work, including the decisions and directions he followed in selecting texts from the esoteric archive for translation into Tibetan.

Chapter 6 is devoted to the Nyingma's response to a new socio-religious situation: the ideology of "treasure texts" (terma). This chapter examines early textual evidence that in earlier times the word "treasure" was applied only to precious artifacts found in the ruins of temples of the ancient empire. Next, we look at the position of the Tibetan emperors, their dynastic heritage, the importance of old temples, guardian spirits, and the developing culture of scripture creation in Tibet.

We then analyze the Nyingma defense of our views (both the "sacred word" (bka ma) and the "treasure texts") as a response to the challenge of translators and neoconservatives. The chapter concludes with a discussion of Nyingma "awareness" (rig pa) as an important contribution to Tibetan religious doctrines, as opposed to the Gnostic emphasis of the newer translations.

Chapter 7 moves us to the end of the eleventh century, when the Tibetans began to systematize and put in order the results of their centuries of effort. Here we present popular Kadampa and Kagyupa religious ideas, as well as new intellectual developments in Buddhist philosophy and Tantric theory. As a classic example of Indian religious volatility, consider Padampa Sangye and his mission to Tsang Province.

The Khon clan is described as a paradigmatic example of a clan-based religious formation, from its mythological origins through the descent of deities, its real position in the early empire, and down to the histories of the Khon clan during the period of fragmentation. We will look at the first real identity of this clan, Khon Konchok Gyelpo, including his training with Drokmi and others, and his founding of the Sakya Monastery.

In Chapter 8 the starting point shifts to the beginning of the twelfth century. It discusses Central Tibet's gaining religious certainty as well as the institutionalization of religious systems. In this regard, the reasons for the growing acceptance of Kalachakra are considered here, as well as doctrinal developments based on the Mahayana philosophy of Chapa Choki Senge, the temporary flowering of the female practice of cho, and the tantric ideology of Gampopa.

The end of the chapter is dedicated to Sachen Kunga Nyingpo, the first of the five great Sakya mentors: his early life and his future literary successes. He labored under a very significant but little known figure, Bari Lotsava, and therefore Bari's teaching of Indian rituals and his contribution to the creation of the Sakya are described here. Sachen's literary activities are also described in some detail, especially with regard to the lamdre. The chapter closes with an analysis of the "short transmission" believed to have been bestowed on Sachen Kunga Nyingpo by Siddha Virupa.

Chapter 9 deals with the second half of the twelfth and the beginning of the thirteenth century. The chapter begins by describing the simultaneous feeling of both crisis and opportunity that the inhabitants of Central Tibet experienced at that time. Here we discuss Gampopa's successors, especially Lama Zhang, the first Karmapa, and also Phagmo Drugpa, and explore the problematic behavior of "mad saints", in particular the shije (zhi-byed) and cho traditions.

In addition, this chapter also analyzes the growing sense of internationalization associated with the influx of Tanguts and Indians into Tibet. Much of the chapter is devoted to describing the lives and successes of Sachen's two sons, Sonam Tsemo and Drakpa Gyaltsen. The activity of Pakpa among the Mongols (as, indeed, any subsequent activity of the Sakya) would hardly have been possible without their assistance. The history of these two brothers, very different from each other in temperament, dates back to the period from the middle of the twelfth to the beginning of the thirteenth centuries.

Finally, the Conclusion summarizes the modus operandi of Indian esotericism as a catalyst for the revival of the culture and institutional life of Central Tibet, although at times it even hindered the political unification of Tibet.

This work concludes with three appendices: a list of possible temples of the Eastern Vinaya, a translation and revision of the main esoteric work of the lamdre tradition, and a correspondence table of early lamdre commentaries surviving by the fourteenth century.

The reader may wonder why the book avoids a direct discussion of the two historical figures with whom I began this Introduction: Sakya Pandita and Pakpa, the fourth and fifth of the "Five Greats" of the Sakya school. I did this for two reasons.

First, Sakya Pandita's writings (as opposed to his missionary work) are almost entirely devoted to the other side of Tibetan Buddhism: scholasticism and its neo-conservative views on the role of monastic Buddhism. This material has been studied and continues to be studied by those who are better prepared than me in terms of presenting the main issues of the life and work of this person, who stood at the origins of Tibetan intellectual history.

However, there is no doubt that for the Mongols, only the esoteric component of Tibetan Buddhism was of particular importance. In addition, it was she who caused the struggle between the clans and social groups of Central Tibet in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, as well as the obvious attraction of the Tanguts to Tibetan Buddhism. The uncle of the Sakya Pandita and the chief teacher of the Sakya esoteric system was Drakpa Gyaltsen, who died only twenty-eight years before the Mongols interfered in the life of his learned nephew.

Given the insignificance of this chronological period, it can be safely assumed that little has changed in the esoteric aspects of the Sakya system during this time. In addition, although Pakpa followed mainly esotericism (like his great uncles and unlike his own uncle), he nevertheless spent most of his life surrounded by the Mongol court, and his activities are best studied in this context. It is also quite clear that the nature of esoteric Buddhism during the Tibetan renaissance and the centrality of the clans during this eminent period require more elucidation, and therefore I have decided to focus my attention on these matters.