The Abbot, or Ironing out History’s Wrinkles

Picking through a manuscript collection piece by piece can be painstaking work, but it’s rarely boring. I never cease to be amazed by the mere fact that these ancient things were written, used and reused by very different people who held them in their hands in a very different place and time. And then there are the occasional magical moments, when you come across something really fascinating that nobody else has noticed before.

This happened to me a few months ago when I was compiling a catalogue with Kazushi Iwao. We were sifting painstakingly through the main series of Chinese manuscripts in the British Library, to see whether there were any Tibetan manuscripts in there that had been overlooked. We came across something that looked sort of familiar… Something about Rasa (the old name of Lhasa) … something about a Brahmin called Ananta.

Aha! The penny dropped. This was part of the story of how Buddhism was introduced to Tibet by the tsenpo Tri Song Detsen. It looked very similar to the version of that story in an important and early Buddhist history called The Testament of Ba. A quick check of that text revealed that yes, this was a fragment of the Testament of Ba.

Now this was exciting (to us at least) because nobody knows when the Testament of Ba was written. Though everyone agrees that it’s an early history, the oldest manuscript that’s been found is from the 12th or 13th century (this version is called the Dba’ bzhed). The fragment we’d found could well be from the 9th century, taking us to only a short while after the actual reign of Tri Song Detsen.

- * *

The fragment tells the story of how the abbot Śāntarakṣita was invited to Tibet by Tri Song Detsen. This was the first stage of the tsenpo’s adoption of Buddhism, overturning the anti-Buddhist policies of his ministers. But when the abbot arrived in Lhasa, Tri Song Detsen had second thoughts, and was worried that this foreigner might be bringing black magic or spirits with him. So the abbot was confined to the Jokhang temple, and interviewed by a minister.

Since the abbot didn’t speak Tibetan, an interpreter had to be found. After a search, a fellow called Ananta was discovered. He was in Tibet because his father had been convicted of a serious crime in Kashmir and had been exiled. So Ananta became the interpreter as the abbot was questioned for three months about his doctrines. Eventually the minister assured Tri Song Detsen that the abbot posed no threat, and he was allowed to begin his task of establishing Buddhism in Tibet.

Now I don’t know about you, but that story doesn’t seem the most auspicious starting-point for Buddhism in Tibet. Later historians didn’t think so either. Even the oldest version of the Testament of Ba changes the language slightly, so that instead of the abbot being confined in the Jokhang (the Tibetan word bcugs is the same used in legal documents for imprisonment) he’s politely “asked to stay” there.

In later versions of the Testament (like the Sba bzhed), the suspicions about the abbot are placed in the minds of the ministers, instead of the Tri Song Detsen himself. This absolves the tsenpo from harbouring bad thoughts about the saintly abbot. This more polite version was the one used by the historian Butön in his famous history of Buddhism. He also dropped the figure of Ananta, with his shady past, from this part of the narrative. And some other historians simply ignored the whole interrogation-of-the-abbot episode.

- * *

Personally, I like the early version of the story, and probably for the same reason that the Tibetan Buddhist historians were uncomfortable with it. It has wrinkles in it that get in the way a seamless narrative of the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet by glorious kings, monks and yogins. It seems more like a record of what “really happened” than a pious story meant to inspire the faithful. You might not agree, and I’m sure that this preference down to my own cultural conditioning. But perhaps you’ll agree that our little manuscript discovery has helped us to see how this particular wrinkle was gradually smoothed out by generations of historians. Which is quite interesting whether you prefer your history wrinkled or smooth.

- * *

References

1. Sam van Schaik and Kazushi Iwao. “Fragments of the Testament of Ba from Dunhuang”. Journal of the American Oriental Society 128.3 (2008 [2009]): 477–487.

2. Pasang Wangdu and Hildegard Diemberger. 2000. The Royal Narrative Concerning the Bringing of Buddha’s Doctrine to Tibet. Wien: Verlag der Osterreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

1. Statue of Śāntarakṣita. Photograph by Matthieu Ricard, (c) Getty Images (click on image for link).

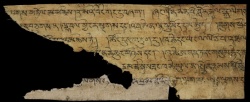

2. The two fragments together: Or.8210/S.9498(A) and Or.8210/S.13683(C).

- * *

Update: Transcriptions of the fragments are now available on the OTDO website here and here. And the images of the fragments, along with the other fragments that they were glued together with, can be seen on the IDP website here and here.

- * *

Pasang Wangdu and Hildegard Diemberger’s translation of the Dba’ bzhed

The mKhan po sent a messenger to prostrate in front of the bTsan po and to inquire about whether he should meet him immediately. [He was] asked: “Please, stay at Pe har for a while.” The bTsan po suspected that there could be some black magic and evil spirits (phra men) from lHo bal [in the doctrine of the mKhan po]”

Then [the bTsan po] ordered Zhang blon chen po sBrang rGya sbra (sgra) legs gzigs, Seng ‘go lHa lung gzigs and ‘Ba’ Sang shi, “You three ministers, go to Ra sa Pe har (vihāra) to meet A tsa rya Bo dhi sa twa and prostrate in front of him.

Then investigate whether I need to suspect the presence of black magic and evil spirits from lHo bal or not.” The three arrived at Ra sa Pe har (= vihāra). There was no translator. So, in six market-places it was ordered that each chief merchant (tshong dpon) had to search for a translator from Kashmir (Kha che) or Yang le. In the lHa sa market three people were found, namely, two Kashmiri lHa byin brothers and the Kashmiri A nan ta.

The two lHa byin brothers were unable to act as translators except for some language of trade. As far as A nan ta is concerned: he was the son of the Brahman sKyes bzang who had commited a serious crime and had been sent into exile in Tibet because according to the law of lHo bal Kashmir (lHo bal kha che) Brahmans could not be executed. [A nan ta] had studied the Brahman sacred scriptures (gtsug lag), grammar (sgra) and medicine, and was therefore able to translate the language of the doctrine.

(Pasang and Diemberger 2000: p.43-45)