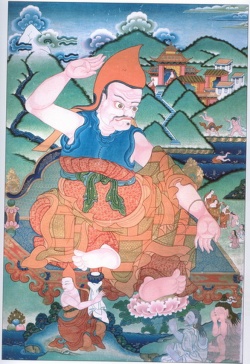

Tsongkhapa (The man from Tsongkha)

Tibetan Buddhism:

Tsongkhapa ("The man from Tsongkha",).

In his two main treatises, the Lamrim Chenmo (), Tsongkhapa meticulously sets forth this graduated way and how one establishes oneself in the paths of sutra and tantra.

With a Mongolian father and a Tibetan mother, Tsongkhapa was born into a nomadic family in the walled city of Tsongkha in Amdo, Tibet (present-day Haidong and Xining, Qinghai) in 1357. It is said that the Buddha Sakyamuni spoke of his coming as an emanation of the Bodhisattva Manjusri in the short verse from the Root Tantra of Manjushri ():

quote|After I pass away

And my pure doctrine is absent,

You will appear as an ordinary being,

Performing the deeds of a Buddha

And establishing the Joyful Land, the great Protector,

In the Land of the Snows.

According to hagiographic accounts, Tsongkhapa's birth was prophesized by the 12th abbot of the Snar thang monastery, and was recognized as such at a young age, taking the lay vows at the age of three before Rolpe Dorje, 4th Karmapa Lama and was named Künga Nyingpo (, 1309-1385), the first abbott of Jakhyung Monastery ().

It was at this early age that he was able to receive the empowerments of Heruka, Hevajra, and Yamantaka, three of the most prominent wrathful deities of Tibetan Buddhism, as well as being able to re received the Kadam lineages and studied the major Sarma tantras under Sakya and Kagyu masters.

He also studied with a Nyingma teacher, the siddha Lek gyi Dorjé (), and his main Dzogchen master was Drupchen Lekyi Dorje (, 1326-1401).

In addition to his studies, he engaged in extensive meditation retreats. He is reputed to have performed millions of prostrations, mandala offerings and other forms of purification practice. Tsongkhapa often had visions of iṣṭadevatās, especially of Manjusri, with whom he would communicate directly to clarify difficult points of the scriptures.

Tsongkhapa was one of the foremost authorities of Tibetan Buddhism at the time. He composed a devotional prayer called the Migtsema Prayer to his Sakya master Rendawa, which was offered back to Tsongkhapa, with the note of his master saying that these verses were more applicable to Tsongkhapa than to himself.

Tsongkhapa died in 1419 at the age of sixty-two. After his death several biographies were written by Lamas of different traditions. Wangchuk Dorje, 9th Karmapa Lama, praised Tsongkhapa as one "who swept away wrong views with the correct and perfect ones." Mikyö Dorje, 8th Karmapa Lama, wrote in his poem In Praise of the Incomparable Tsong Khapa:

The Most Beautiful Girls Live Here!

The Most Beautiful Girls Live Here!

You Ride This Bike Lying Down, and It Feels like You're Flying

You Ride This Bike Lying Down, and It Feels like You're Flying

Discover a New World of Vector Art

Discover a New World of Vector Art

Top 10 Visions of the World in 1000 Years

Top 10 Visions of the World in 1000 Years

When the teachings of the Sakya, Kagyue, Kadam

And Nyingma sects in Tibet were declining,

You, O Tsong Khapa, revived Buddha's Doctrine,

Hence I sing this praise to you of Ganden Mountain.

Tsongkhapa was acquainted with all Tibetan Buddhist traditions of his time, and received lineages transmitted in the major schools.Crystal Mirror VI : 1971, Dharma Publishing, page 464, 0-913546-59-3 His main source of inspiration was the Kadam school, the legacy of Atiśa. Tsongkhapa received two of the three main Kadampa lineages (the Lam-Rim lineage, and the oral guideline lineage) from the Nyingma Lama, Lhodrag Namka-gyeltsen; and the third main Kadampa lineage (the lineage of textual transmission) from the Kagyu teacher Lama Umapa.

Tsongkhapa’s teachings drew upon these Kadampa teachings of Atiśa, emphasizing the study of Vinaya, the Tripiṭaka, and the Shastras. Atiśa’s Lamrim inspired Tsongkhapa’s Lamrim Chenmo, which became a main text among his followers.

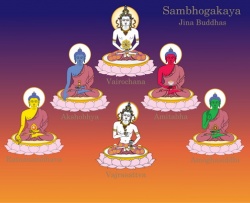

He also practised and taught extensively the Vajrayana, and especially how to bring the Sutra and Tantra teachings together, wrote works that summarized the root teachings of the Buddhist philosophical schools, as well as commentaries on the Prātimokṣa, Prajnaparamita, Candrakirti’s Madhyamakavatara, logic, Pure Land and the Sarma tantras.

According to Thupten Jinpa, the following elements are essential in a coherent understanding of Tsongkhapa's understanding and interpretation of the Madhyamaka refutation of essentialist ontology:

- Tsongkhapa's distinction between the domains of the conventional and ultimate perspectives;

- Tsongkhapa's insistence on a prior, correct conceptual identification of the object of negation;

- Tsongkhapa's differentiation of the various connotations of the all-important term 'ultimate' (paramartha skt.);

- Tsongkhapa's distinction he draws between that which is not found and that which is negated.

Tsongkhapa's first principal work, The Golden Garland of Eloquence () demonstrated a philosophical view in line with the Yogacara schoolNgawang Samten/Garfield. Ocean of Reasoning. OUP 2006, page x and, as became one of his hallmarks, was more influenced by Indian authors than contemporary Tibetan sources.

At this time his account of the Madhyamaka focused on its interpretation as a negative dialectic structure.

After this early work, his attention focussed on the Prajnaparamita sutras and Dharmakirti's Pramanavartika, and it is this emphasis that dominates all his later philosophical works.

Garfield suggests his stance as: quote|A complete understanding of Buddhist philosophy requires a synthesis of the epistemology and logic of Dharmakirti with the metaphysics of Nagarjuna|:

Tsongkhapa was a proponent of Candrakirti's Consequentialist, or prasangika interpretation of the Madhyamaka teachings on sunyata (emptiness), rejecting the Svatantrika point of view.

According to Tsongkhapa, the Prāsaṅgika-approach is the only acceptable approach within Madhyamaka, rejecting the Svatantrikas because they state that the conventional reality is "established by virtue of particular characteristics" (rang gi mtshan nyid kyis grub pa):

The classification into Prasangika and Svatantrika originated from their different usages of reason to make "emptiness" understandable. The Svātantrikas strive to make positive assertions to attack wrong views, whereas the Prasangikas draw out the contradictory consequences (prasanga) of the opposing views.

In Tsongkhapa's reading, the difference becomes one of the understanding of emptiness, which centers on the nature of conventional existence.

The Svātantrikas state that conventional phenomena have particular characteristics, by which they can be distinguished, but without an ultimately existing essence.

In Tsongkhapa's understanding, these particular characteristics are posited as establishing that conventionally things do have an intrinsic nature, a position which he rejects:

Tsongkhapa's rejection of Svatantrika has been severely criticised within the Tibetan tradition, qualifying it as Tsongkhapa's own invention, and therefore "unwarranted and unprecedented within the greater Madhyamaka tradition."

Although Tsongkhapa is regarded as the great champion of the Prasangika-view, according to Thomas Doctor, Tsongkhapa's views on the difference between Prasanghika and Svatantrika are preceded by a 12th-century author, Mabja Jangchub Tsondru (d. 1185).

Tsongkhapa saw emptiness as a consequence of pratītyasamutpāda (dependent arising), the teaching that no dharma ("thing") has an existence of its own, but always comes into existence in dependence on other dharmas.

Tsongkhapa's view on "ultimate reality" is condensed in the short text In Praise of Dependent Arising c.q. In Praise of Relativity c.q. The Essence of Eloquency. It states that "things" do exist conventionally, but ultimately everything is dependently arisen, and therefore void of inherent existence:

This means that conventionally things do exist, and that there is no use in denying that. But it also means that ultimately those things have no 'existence of their own', and that cognizing them as such results from cognitive operations, not from some unchangeable essence. Tsongkhapa:

It also means that there is no "transcendental ground," and that "ultimate reality" has no existence of its own, but is the negation of such a transecendental reality, and the impossibility of any statement on such an ultimately existing transcendental reality: it is no more than a fabrication of the mind. Susan Kahn further explains:

For Tsongkhapa, calming meditation alone is not sufficient, but should be paired to rigorous, exact thinking "to push the mind and precipitate a breakthrough in cognitive fluency and insight." According to Patrick Jennings,

Almost as soon as Tsongkhapa's later works were published, they became highly influential, and have remained that way to present. However, opinion on whether or not his views are correct remain hotly debated. As Jinpa, Garfield and others point out, this controversy remains particularly active, and can be easily seen in modern published works.

Some of the greatest subsequent Tibetan scholars have become famous for their own works either defending or attacking Tsongkhapa's views.

His critics deemed Tsongkhapa's ideas to be unacceptable innovations of his own, instead of following the established tradition. According to Thupten Jinpa, the Gelugpa school sees Tsongkhapa's ideas as mystical revelations from the bodhisattva Manjusri,Jinpa, Thupten. Self, Reality and Reason in Tibetan Philosophy. Routledge 2002, page 17. whereas Gorampa accused him of being inspired by a demon.

According to Van Schaik, these criticisms furthered the establishment of the Gelupga as an independent school:

Sam van Schaik says that Tsongkhapa "wanted to create something new" and that the early Gandenpas defined themselves by responding to accusations from the established schools:

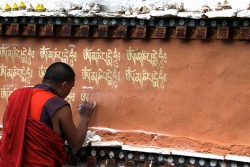

Tsongkhapa emphasised a strong monastic Sangha. With the founding of the Ganden monastery in 1409, he laid down the basis for what was later named the Gelug ("virtuous ones") order.

At the time of the foundation of the Ganden monastery, his followers became to be known as "Gandenbas." Tsongkhapa himself never announced the establishment of a new monastic order.

After Tsongkhapa had founded Ganden Monastery in 1409, it became his main seat. He had many students, among whom Gyaltsab Je (1364–1431), Khedrup Gelek Pelzang, 1st Panchen Lama (1385–1438), Togden Jampal Gyatso, Jamyang Choje, Jamchenpa Sherap Senge, and the 1st Dalai Lama (1391–1474), were the most outstanding. After Tsongkhapa’s passing his teachings were held and kept by Gyaltsab Dharma Rinchen and Khedrub Gelek Pälsang. From then on, his lineage has been held by the Ganden Tripas, the throne-holders of Ganden Monastery, among whom the present one is Thubten Nyima Lungtok Tenzin Norbu, the 102nd Ganden Tripa.

After the founding of Ganden Monastery by Tsongkhapa, Drepung Monastery was founded by Jamyang Choje, Sera Monastery was founded by Chöje Shakya Yeshe and the 1st Dalai Lama founded Tashilhunpo Monastery.

Many Gelug monasteries were built throughout Tibet but also in China and Mongolia.

He spent some time as a hermit in Pabonka Hermitage, which was built during Songsten Gampo times, approximately 8 kilometres north west of Lhasa. Today, it is also part of Sera.

Among the many lineage holders of the Gelugpas there are the successive incarnations of the Panchen Lama as well as the Chagkya Dorje Chang, Ngachen Könchok Gyaltsen, Kyishö Tulku Tenzin Thrinly, Jamyang Shepa, Phurchok Jampa Rinpoche, Jamyang Dewe Dorje, Takphu Rinpoche, Khachen Yeshe Gyaltsen, Trijang Rinpoche+, Domo Geshe Rinpoche, and many others.

The annual Tibetan prayer festival Monlam Prayer Festival was established by Tsongkhapa. There he offered service to ten thousand monks. The establishment of the Great Prayer Festival is seen as one of his Four Great Deeds. It celebrates the miraculous deeds of Gautama Buddha.

According to Karl Brunnholzl, Tsongkhapa's Madhyamaka has become widely influential in the western understanding of Madhyamaka:

Tsongkhapa promoted the study of logic, encouraged formal debates as part of Dharma studies, and instructed disciples in the Guhyasamāja, Kalacakra, and Hevajra Tantras. Tsongkhapa's writings comprise eighteen volumes, with the largest amount being on Guhyasamāja tantra. These 18 volumes contain hundreds of titles relating to all aspects of Buddhist teachings and clarify some of the most difficult topics of Sutrayana and Vajrayana teachings. Tsongkhapa's main treatises and commentaries on Madhyamaka are based on the tradition descended from Nagarjuna as elucidated by Buddhapālita and Candrakīrti.

Major works among them are:

- Essence of True Eloquence (drang nges legs bshad snying po; full title: gsung rab kyi drang ba dang nges pai don rnam par phye ba gsal bar byed pa legs par bshad pai snying po),

- Ocean of Reasoning: A Great Commentary on Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhyamakakarika (dbu ma rtsa ba'i tshig le'ur byas pa shes rab ces bya ba'i rnam bshad rigs pa'i rgya mtsho),

- Brilliant Illumination of the Lamp of the Five Stages / A Lamp to Illuminate the Five Stages (gsang ’dus rim lnga gsal sgron),

- Golden Garland of Eloquence (gser phreng) and

- The Praise of Relativity (rten ’brel bstod pa).

- Life and Teachings of Tsongkhapa, Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 2006, ISBN 978-8186470442

- The Great Treatise On The Stages Of The Path To Enlightenment, Vol. 1, Snow Lion, ISBN 1-55939-152-9

- The Great Treatise On The Stages Of The Path To Enlightenment, Vol. 2, Snow Lion, ISBN 1-55939-168-5

- The Great Treatise On The Stages Of The Path To Enlightenment, Vol. 3, Snow Lion, ISBN 1-55939-166-9

- Dependent-Arising and Emptiness: A Tibetan Buddhist Interpretation of Mādhyamika Philosophy, trans. Elizabeth Napper, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 0-86171-364-8: this volume "considers the special insight section of" the Lam Rim (p. 8).

- The Medium Treatise On The Stages Of The Path To Enlightenment - Calm Abiding Section translated in "Balancing The Mind: A Tibetan Buddhist Approach To Refining Attention", Shambhala Publications, 2005, ISBN 978-1-55-939230-3

- The Medium Treatise On The Stages Of The Path To Enlightenment - Insight Section translated in "Life and Teachings of Tsongkhapa", Library of Tibetan Works and Archives, 2006, ISBN 978-8186470442

- The Medium Treatise on the Stages of the Path to Enlightenment (Calm Abiding Section) translated in B. Alan Wallace, Dissertation, 1995, (Wylie: byang chub lam gyi rim pa chung ba)

- Lam Rim - Small Treatise

- Golden Garland of Eloquence - Volume 1 of 4: First Abhisamaya, Jain Pub Co, 2008, ISBN 0-89581-865-5

- Golden Garland of Eloquence - Volume 2 of 4: Second and Third Abhisamayas, Jain Pub Co, 2008, ISBN 0-89581-866-3

- Golden Garland of Eloquence - Volume 3 of 4: Fourth Abhisamaya, Jain Pub Co, 2010, ISBN 0-89581-867-1

- Golden Garland of Eloquence - Volume 4 of 4: Fourth Abhisamaya, Jain Pub Co, 2013, ISBN 978-0-89581-868-3

- Ocean of Reasoning: A Great Commentary on Nagarjuna’s Mulamadhyamakakarika, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-514733-2

- Essence of True Eloquence, translated in The Central Philosophy of Tibet, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-69102-067-1

- Guided Tour Through the Seven Books of Dharmakirti, translated in A Millennium of Buddhist Logic, Motilal Barnasidass, 1999, ISBN 8-12081-646-3

- The Fulfillment of All Hopes: Guru Devotion in Tibetan Buddhism, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 0-86171-153-X

- Tantric Ethics: An Explanation of the Precepts for Buddhist Vajrayana Practice, Wisdom Publications, ISBN 0-86171-290-0

- The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra - Chapter 1 of 13, translated in Tantra in Tibet, Shambhala Publications, 1987, ISBN 978-0-93-793849-2

- The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra - Chapter 2 and 3 of 13, translated in Deity Yoga, Shambhala Publications, 1987, ISBN 978-0-93-793850-8

- The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra - Chapter 4 of 13, translated in Yoga Tantra, Shambhala Publications, 2012, ISBN 978-1-55-939898-5

- The Great Exposition of Secret Mantra - Chapter 11 and 12 of 13, translated in Great Treatise on the Stages of Mantra: Chapters XI–XII (The Creation Stage), Columbia University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-1-935011-01-9

- The Six Yogas of Naropa: Tsongkhapa's Commentary, Snow Lion Publications, ISBN 1-55939-234-7

- Lamp of the Five Stages

- Brilliant Illumination of the Lamp of the Five Stages, Columbia University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1-93-501100-2

- A Lamp to Illuminate the Five Stages, Library of Tibetan Classics, 2013, ISBN 0-86171-454-7

- Ocean of Eloquence: Tsong Kha Pa’s Commentary on the Yogacara Doctrine of Mind, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-1479-5

- Other

- The Splendor of an Autumn Moon: The Devotional Verse of Tsongkhapa Wisdom Publications, ISBN 978-0-86171-192-5

- Three Principal Aspects of the Path, Tharpa Publications

- Stairway to Nirvāṇa: A Study of the Twenty Saṃghas based on the works of Tsong-kha-pa, James B. Apple, State University of New York Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0791473764