The Story of the Horse-King and the Merchant Siṃhala in Buddhist Texts

Naomi Appleton

DPhil. candidate in Buddhist Studies,

Oriental Institute, Oxford University

naomi.appleton@orinst.ox.ac.uk

ABSTRACT: The Aśvarāja story relates the adventures of a caravan of merchants ship- wrecked on an island of demonesses and rescued by a fl ying horse, the aśvarāja , ‘king of horses’. The Siṃhala story continues this narrative to include the chief merchant, Siṃhala, being followed home by a demoness, who tries to get him back before seducing and eating the king. Siṃhala is crowned king and invades the island. Each story has many versions, both Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna.

This paper examines fi ve key versions: birth story with ‘ocean of saṃsāra ’ metaphor; political and quasi-historical narrative of the invasion of Sri Lanka by the Sinhalese; warning that ‘all women are demonesses’; glorifi cation of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara; and Newar warning of the dangers of travelling to Tibet. Each version reveals some of the issues that its community is preoccupied with.

The Aśvarāja story, and its extended version the Siṃhala story, are found in over twenty versions in Buddhist texts alone, in many different languages and both Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna forms. Like many Buddhist narratives, the stories have received rather uneven scholarly attention. Translators and editors of individual versions have freely commented upon their own text, with some interesting suggestions, but without a sufficiently broad awareness of the different versions. The only comprehensive study of any one version is by Lewis, who examines the tradition surrounding the Siṃhala story in Nepal (Lewis, 1995, 2000).

Lienhard too addresses this in his translation of a painted Nepalese scroll of the story, where he also indulges in a broad survey of the story’s occurrence within Asian literature, although his comments in this area are predominantly descriptive rather than analytical (Lienhard, 1985). To my knowledge no scholar has attempted a full comparison of the different versions, although Grey and Panglung both off er 1.

This article is drawn from my MPhil. thesis and has seen several incarnations as conference papers, including one presented at the 2006 UKABS conference. My thanks go to everyone who has commented on both the thesis and earlier versions of this article, but most especially to my

inspiring and ever supportive supervisor Dr Andrew Skilton.

BUDDHIST STUDIES REVIEW

incomplete concordances of versions (Grey, 2000; Panglung, 1981). Grey’s list of sources is indicative of the lack of scholarly interest in the story: most references are either to studies of Asian art, or to the Valāhassa-jātaka of the Jātakatthavaṇṇanā , which is frequently but erroneously cited as the ‘original’ version. 2

In this article I will not provide a comprehensive analysis of this story cycle, 3 but I will brie fl y present the development of the plot and characters over time, focusing upon fi ve particularly revealing forms that the stories take. First I will present the basic form of the Aśvarāja story, which is a standard Buddhist birth story with an ocean of saṃsāra metaphor.

Secondly I will look at how the Siṃhala story presents a political and quasi-historical narrative of the invasion of Sri Lanka by the Sinhalese people, which forms an alternative origin myth to that found in the chronicles of the island. Thirdly I will examine the declaration within some versions of the story that ‘all women are demonesses’.

Fourthly I will exam- ine the appropriation of both stories by Mahāyāna Buddhism in order to glorify the compassionate bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara.

Finally I will present the Newar versions, which geographically transplant the story in order to transform it into a warning to merchants of the dangers of travelling to Tibet, and in particular the folly of taking a Tibetan woman as a wife. In The Folktale , Stith Thompson (1977: 10) observes that ‘the plot structure of the tale is much more stable and more persistent than its form’.

This statement forms the backbone of this article, which will examine how the subtle changes in detail, in a story where the main events are fi xed, can reveal the needs and preoc- cupations of the redactors and audiences. Such preoccupations include some of the most fundamental issues that humanity has to deal with, relating to soteriology, self-control, the need for a saviour, gender, politics, and race.

Even by restricting my study to fi ve versions and a text-historical methodology, I hope to demonstrate that narrative can reveal much about social, cultural and religious contexts, and thus that a study of narrative is a crucial ingredient in the study of Buddhism. 4

Before we begin our analysis of the narrative cycle through its five significant forms, it will be helpful to outline the stories and the texts that contain them. Any categorisation of this cycle of narratives will be in some way inadequate, since there is great variation between versions.

The drawing of boundaries between this and other cycles of narrative drawn from common elements is a delicate endeavour, and to complicate matters further, some texts contain more than one version. However, the stories do broadly fall into two categories, the short and the long form, which I term the Aśvarāja and Siṃhala stories respectively.

Each of these also has a Mahāyāna form, thus we have four basic stories contained within the cycle. 2. See note 9 below. 3. To a certain extent this is found in my MPhil thesis, although it is also an ongoing project. For example, Dr Ulrike Roesler recently brought two more versions to my attention, in Tibetan commentaries from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries. 4.

My text-historical approach is partly limited by the lack of evidence about the uses of versions of the stories in Buddhist societies, with the exception of the Newar situation, studied by Todd Lewis (1995, 2000).

In the Aśvarāja story, some merchants are shipwrecked on an island where they are seduced by demonesses who are disguised as beautiful maidens. They unwit- tingly settle down with the demonesses as wives, and enjoy the riches of the island.

The chief merchant is suspicious at a prohibition to take the road south and, upon taking it, discovers a fortress imprisoning many merchants. These reveal to him the danger he and his men are in. The chief merchant leads his companions to the shore where they fi nd a magical horse, the aśvarāja , ‘horse-king’, who is the Bodhisatta .

The horse tells them not to look back towards the island, and carries them safely to India. The Aśvarāja story in this form is found in the Abhiniṣkramaṇa Sūtra , 5 and the Bhaiṣajyavastu of the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya . 6 In the versions in the Mahāvastu 7 and the Lie Du Ji Jing 8 some of the merchants look back and fall into the ocean to be devoured by the demonesses.

In the Valāhassa-jātaka of the Jātakatthavaṇṇanā , some merchants instead stay behind, refusing to believe their chief ’s declaration about the true nature of their new wives. 9

In addition to these full tellings, there are references to the Aśvarāja story in the Lalitavistara , 10 Rāstrapālaparipṛcchā , 11 and Khotanese Jātakastava, 12 as well as two verses in the Udānavarga 13 that parallel those in the Jātakatthavaṇṇanā and Mahāvastu . 5. This primarily biographical text was translated into Chinese (T190) from a Sanskrit original in the sixth century (Beal, 1985 [1875]: 332–40). 6.

This is available in Tibetan; the Sanskrit is not extant. A summary is found in Panglung (1981: 41–2).

7. A Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit text containing a mixture of biographical stories, probably compiled

between the second century BCE and the fourth century CE (Senart, 1882–97: III, 67–90; Jones,

1949–56: III, 70–93).

8. This is a collection of jātaka stories exemplifying the Bodhisatta ’s acquisition of the six perfections which were translated into Chinese (T152) in the third century CE (Chavannes, 1962: I, 224–6 [no. 59]). The above title is in the Pinyin form (Wade-Giles form Liu Tu Chi Ching ); Chavannes transcribes it using the French EEEO method, as Lieou Tou Tsi King . 9.

Only the verses of this Theravāda text are considered to be canonical, though the text as a whole, which reached its fi nal form in the fi fth century, is held in high regard (Fausbøll, 1877–96: II, 127–30; Cowell, et al. 1895–1907: II, 89–91).

Although perhaps the best known version, the Valāhassa-jātaka contains a barely coherent narrative with several indications that it is in fact a crude and clumsy abbreviation badly aff ected by confusion between diff erent versions. One piece of evidence for this is the fact that the merchants’ refusal to listen to their chief is inconsistent with the (canonical) verse, which speaks of merchants refusing to listen to the horse.

A full discussion of this may be found in my thesis (Appleton, 2004: 61ff .). 10. A primarily biographical text from around the fi rst century CE that survives in Sanskrit and Tibetan (Bays, 1983: I, 253). 11. This is a Mahāyāna text in a mixture of Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit verse and Sanskrit prose from around the sixth century.

The text as a whole deals with what it means to be a good and bad monk, but the fi rst chapter contains 50 verses each relating a jātaka , to illustrate the virtues acquired by the Buddha (Finot, 1957: 26; Ensink, 1952: 27). There are also two Chinese transla- tions (6th and 10th century), one Tibetan, and one Mongolian. 12.

This Khotanese verse text, probably translated from a (lost) Sanskrit original in around the tenth century, consists of fi fty jātaka stories, told brie fl y (in a couple of verses each), with a prologue and words of homage to the Buddha (Dresden, 1955: 425, vv. 24–6). 13. Bernhard (1965: 282, vv. 14–15); Rockhill (1883: 92, vv. 10–11). The full story is apparently found in the Chinese commentary (T212) although I have not been able to access this.

The Siṃhala story begins in the same way as the Aśvarāja story, but the chief merchant, who is called Siṃhala, is the Bodhisatta . He is the only merchant stead- fast enough to make it home; all his companions weakly look back, fall into the ocean and are devoured by their former wives. Siṃhala is followed home by a demoness, who poses as his wife and creates an illusory child to garner sympathy from his parents.

When she fails to win him back, she goes to the king and seduces him, before summoning her friends and devouring the entire royal household. Siṃhala chases the demonesses from the palace, is crowned king and invades the island, expelling or killing the demonesses.

The Siṃhala story is found in almost identical versions in the Vinayavibhaṅga of the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya and the Divyāvadāna , though in the latter text the Aśvarāja story is abbreviated. 14 The Xi- you-ji 15 by Xuanzang tells a simpler version as part of a narrative of the arrival of the Sinhalese people on Sri Lanka, whereas the Lie Du Ji Jing contains a version that omits the invasion of the island altogether. 16 The Rāstrapālaparipṛcchā contains a reference to the Siṃhala story, in addition to its reference to the Aśvarāja

story. 17

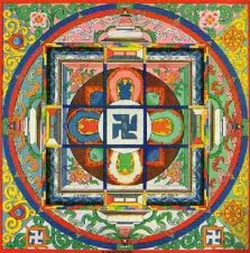

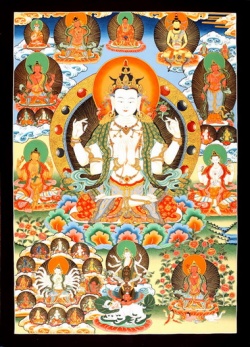

The Mahāyāna Aśvarāja story is much the same as the non-Mahāyāna form, except that the merchant is identi fi ed as the Buddha-to-be and the horse is the compassionate Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara. Rather than discovering it for him- self, the truth about the women on the island is revealed to Siṃhala by either Avalokiteśvara or one of the demonesses. 18

The Mahāyāna Aśvarāja story is fi rst found in the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra , 19 which then forms the source for versions in the rGyal-rabs gsal-ba’i me-long 20 and Ma-ni bka’-‘bum . 21 It is clearly told in awareness of 14. An edition of the Divyāvadāna is provided by Cowell & Neil (1886: 523–8), and the partial transla- tion by Tatelman contains this story (2005: 309–415).

Huber (1906: 22–4) and Schlingloff (1988: 257–63) provide summary translations based on both the Divyāvadāna and Vinayavibhaṅga , the former as part of an argument that stories in the Divyāvadāna are extracted from the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya . 15. A seventh-century travelogue by a Chinese pilgrim (Beal, 1981 [1884]: II, 240–46). 16. Chavannes (1962: I, 122–6 [no.

37]). The version of the Siṃhala story in the Lie Du Ji Jing also omits the crowning of the chief merchant – who is not named – as king. It is possible that this represents the story mid-point in its development from Aśvarāja to Siṃhala story, although it could equally easily be an abbreviation. The frame story is the same as in the Vinayavibhaṅga and Divyāvadāna , though the characters are not named. 17.

Finot (1957: 23); Ensink (1952: 24). 18. In the earlier Mahāyāna versions Avalokiteśvara appears in a lamp to warn Siṃhala. However, when the story (in the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra ) was translated into Tibetan there was some confusion over the term used for lamp ( ratikara ) so the Tibetan versions instead have either a voice from nowhere or a demoness speaking in her sleep.

Regamey (1965) and Lienhard (1993) provide a full discussion of the etymology of the term, and the whole situation is discussed in full in my thesis (Appleton, 2004: 90–93). 19. A Sanskrit prose text from no later than the sixth century (Burnouf, 1890; Mette, 1997: 50-60 [1607b–1612b]; Vaidya, 1961: 284–8).

A critical edition and translation of the story from this text may be found in my thesis (Appleton 2004: 21–52). 20. A fourteenth-century chronicle by Bla-ma dam-pa bSod-nams rgyal-tshan (Kuznetsov, 1997: 36–41; Sørensen, 1994: 117–24; Wenzel, 1888: 504–9). 21. An apocryphal ( gter-ma ) text from around the twelfth century, ascribed to Srong-btsan sgam-po.

the Siṃhala story, and may even be a conscious abbreviation of a version such as that in the Vinayavibhaṅga of the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya . 22 The Mahāyāna Siṃhala story again identi fi es the horse with Avalokiteśvara, who also appears in a lamp to warn Siṃhala of his predicament. The story continues as in the non-Mahāyāna form.

This version is fi rst found in the Guṇakāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra , which borrows much of its content from the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra , although in this case it must also have used a version of the Siṃhala story. 23 The Guṇakāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra became a source for many re-tellings by the Newars of the Kathmandu valley, 24 whilst Xuanzang’s travelogue inspired Japanese versions in the Uji Shūi Monogatari and Konjaku Monogatari . 25 THE JĀTAKA OF THE HORSE-KING We may begin our survey of versions with the simple birth story, or jātaka , which is the basic form of the Aśvarāja story. As a jātaka , one of the characters must be identi fi ed as the Bodhisatta , and in this case it is the horse who is the Buddha-to- be.

He is not only compassionate in off ering the merchants a way of leaving the island, but is also a teacher, warning the merchants that they can only escape if they remain untempted by the demonesses ( rakkhasīs ) and steadfastly look ahead.

The (canonical) verses of the jātaka in the Jātakatthavaṇṇanā read: Those people who will not observe the Buddha’s instructions, shall have misfortune, as the merchants did on account of the demonesses. And those who will observe the Buddha’s instructions, shall go safely to the other shore, as the merchants did by means of Valāha.

26 Sørensen (1994) provides some comment on the ways in which this version diff ers from that in the rGyal-rabs gsal-ba’i me-long .

22. The likely sources for the story in the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra and Guṇakāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra are discussed in my thesis (Appleton, 2004: 86ff .).

23. A fi fteenth-century Sanskrit verse text (Chandra, 1999: 158–202; Iwamoto, 1967: 321–36). Iwamoto’s edition is much more reliable. See Tuladhar-Douglas (2006) for a discussion of the sources for the Guṇakāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra and its relation to the Kāraṇḍavyūha Sūtra . I suspect the

Vinayavibhaṅga or Divyāvadāna is the source for the extra material in this story (see previous note).

24. Lewis (1995: 153–69; 2000: 54–80); Lienhard (1985). Lienhard’s bibliography contains references to more versions in later Newari texts.

25. The Uji Shūi Monogatari , a compilation from the thirteenth century (Mills, 1970: 266–9), and itstwelfth-century predecessor the Konjaku Monogatari , contain practically identical versions of the Siṃhala story.

26. Valāha is the name of the horse in this version (my translation from Fausbøll, 1877–96: II, 130: ye na kāhanti ovādaṃ narā Buddhena desitaṃ / vyasanan te gamissanti rakkhasīhi va vāṇijā // ye cakāhanti ovādaṃ narā Buddhena desitaṃ / sotthiṃ pāraṃ gamissanti vālāheneva vāṇijā /). The verses have parallels in the Mahāvastu (Senart, 1977: III, 89) and Udānavarga (Bernhard, 1965: 282). These verses diff er from the Pāli in two main ways: the people ‘have faith in the word of the Buddha’ ( śraddhāsyanti … buddhasya śāsanam (UV) śraddadhiṣyanti vacanaṃ dharmarājino (MV)) rather than