Difference between revisions of "Exorcising the Mandala: Kālacakra and the Neo-Pentecostal Response"

(Created page with " Laura Harrington Boston University Department of Religion Abstract Since the late 1990s, the Dalai Lama's "Kalachakra for World Peace" initiation has emer...") |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

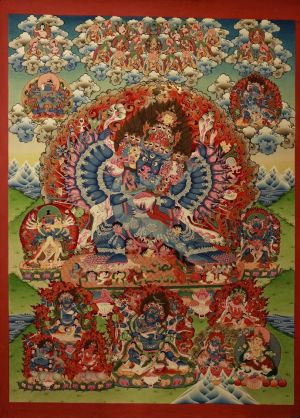

| + | [[File:Yamantaka Vajrabhairava Yab-Yum with main Lamas, Yidams and protectors of Gelugpa tradition.jpg|thumb]] | ||

| Line 6: | Line 7: | ||

| + | by Laura Harrington | ||

| − | + | {{Wiki|Boston University}} | |

| − | + | Department of [[Religion]] | |

| − | |||

| + | ===Abstract=== | ||

| − | |||

| + | Since the late 1990s, the [[Dalai Lama's]] "[[Kalachakra]] for [[World Peace]]" [[initiation]] has emerged as a central site where [[Tibetan Buddhism]] and its relationship to the [[West]] have been [[imagined]] and acted upon by a {{Wiki|movement}} within evangelical [[Christianity]] called [[Spiritual]] Mapping. In Mapping [[understanding]], the [[Kalacakra]] | ||

| − | + | is a [[vehicle]] by which the current [[Dalai Lama]] prepares for the end times by seeking to [[transform]] [[America]] into "a [[universal]] Buddhocracy" called the [[Kingdom of Shambhala]]. [[Tibetan Buddhism]] is, in short, a {{Wiki|missionary}} competitor for global [[religious]] {{Wiki|domination}}. Here, the Tibetan-evangelical encounter is presented | |

| − | + | as the by-product of the simultaneous globalizations of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] and Evangelicalism with the [[human rights]] [[discourse]] in late twentieth century [[America]]. The "[[exorcism]] of the [[mandala]]" is read as both by-product and critique of globalization, and to engender a thoughtful re-evaluation of long-standing [[Buddhist Studies]] analytics. | |

| − | |||

| + | n the spring of 2004, 5,000 [[people]] from around the [[world]] [[gathered]] in {{Wiki|Toronto}}, [[Canada]] to attend the largest public [[Buddhist ritual]] in the contemporary [[world]]: the "[[Kalachakra]] for [[World Peace]]," an eleven day program comprising [[Tibetan Buddhist]] teachings, [[ritual dances]] and [[esoteric ritual]] [[empowerments]] that would authorize their participants to practice the advanced [[meditations]] of the [[Kālacakra]] [[Tantras]]. Few members of its audience were [[skilled]] enough to engage | ||

| − | + | in such practices. Rather, they were there to watch and learn from its presiding [[lama]]: [[His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama]] of [[Tibet]]. | |

| + | The [[visual]] centerpiece of the [[initiation]] was a multi-colored, nine-foot [[sand mandala]]: "a [[symbolic]] [[representation]] of the [[Kalachakra deity]], his palace, and | ||

| − | + | 721 surrounding [[deities]]" (Capital Area [[Tibetan]] Association, 2011) publically [[constructed]] by a team of [[monks]] from the [[Dalai Lama's]] [[own]] [[Namgyal monastery]] (Fig 1 and 2). On the final day of the program, its colored sand particles—"blessed by the [[Buddhas]] residing in the mandala"—were poured by [[His Holiness]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | into the waters of Lake [[Ontario]] "in an act of [[blessing]] the surrounding" and to further the [[Kālacakra's]] broader [[mission]] to "serve(s) as a [[universal]] [[prayer]] for the [[development]] of the [[ethics]] of [[peace]] and [[harmony]] within one's [[self]] and [[humanity]]" ([[Canadian]] [[Tibetan]] Association of {{Wiki|Toronto}}, 2004) . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | EXCORCISING THE MANDALA | + | ===[[EXCORCISING THE MANDALA]]=== |

| − | Across the Great Lakes, the creation and disbursement of the Kālacakra sand mandala was invoking a very different reception. A Pentecostal Christian minister named Apostle Jim Gosa1 was leading a team in a chain of prayer sessions around the perimeter of the Lake to prevent the Tibetan spirits that would be poured into the waters from being dispersed into the adjacent lands. "With the authority and dominion by God" and "in the name of the Holy | + | Across the Great Lakes, the creation and disbursement of the [[Kālacakra]] [[sand mandala]] was invoking a very different {{Wiki|reception}}. A Pentecostal [[Christian]] [[minister]] named Apostle Jim Gosa1 was leading a team in a chain of [[prayer]] sessions around the perimeter of the Lake to prevent the [[Tibetan]] [[spirits]] that would be poured into the waters from being dispersed into the adjacent lands. "With the authority and dominion by [[God]]" and "in the [[name]] of the {{Wiki|Holy}} |

| − | Spirit," Apostle Gosa later explained, "I commanded the spirits of the lake to shut their mouths…." (Gosa, 2008). These self-avowed Spiritual Warriors were seeking to avert the increased "territorial power of Buddhism" (The Original World Changers International, n.d.) and anti-Christian sentiment posed by Tibetan Buddhism in general, and by the Kālacakra initiation in particular.2 | + | [[Spirit]]," Apostle [[Gosa]] later explained, "I commanded the [[spirits]] of the lake to shut their mouths…." ([[Gosa]], 2008). These self-avowed [[Spiritual]] [[Warriors]] were seeking to avert the increased "territorial power of [[Buddhism]]" (The Original [[World]] Changers International, n.d.) and anti-Christian sentiment posed by [[Tibetan Buddhism]] in general, and by the [[Kālacakra initiation]] in particular.2 |

| − | Fig. 1: Kālacakra sand mandala. Photograph by Martin Brauen. Reproduced with permission. | + | Fig. 1: [[Kālacakra]] [[sand mandala]]. Photograph by Martin Brauen. Reproduced with permission. |

| − | 1 "Jim Gosa" is a pseudonym. 2 The larger history of Christian missionary engagement with Tibetan Buddhism is complex and outside of the scope of this work. One important strand of missionary perception saw Tibet as largely impervious to Christian conversion; even in the heyday of Western missions to Asia | + | 1 "Jim [[Gosa]]" is a pseudonym. 2 The larger history of [[Christian]] {{Wiki|missionary}} engagement with [[Tibetan Buddhism]] is complex and outside of the scope of this work. One important strand of {{Wiki|missionary}} [[perception]] saw [[Tibet]] as largely impervious to [[Christian]] [[conversion]]; even in the heyday of [[Western]] missions to {{Wiki|Asia}} |

| − | (1850 to 1950), "no mission society was able to establish a lasting base in central Tibet" (Bray in Dodin 2001, 21). Contemporary Christian missions continue missionary efforts in Tibet proper and towards Tibetan immigrants in the United States. Interestingly, some of the most vigorous efforts are by Asian missionaries.; for example, the Majority World movement of South Korea (Wan 2009). | + | (1850 to 1950), "no [[mission]] [[society]] was able to establish a lasting base in [[central Tibet]]" (Bray in Dodin 2001, 21). Contemporary [[Christian]] missions continue {{Wiki|missionary}} efforts [[in Tibet]] proper and towards [[Tibetan]] immigrants in the [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]]. Interestingly, some of the most vigorous efforts are by {{Wiki|Asian}} [[missionaries]].; for example, the Majority [[World]] {{Wiki|movement}} of {{Wiki|South Korea}} (Wan 2009). |

| − | This group was not acting alone. In communities throughout the United States, Kālacakra-centered exorcisms and prayer events were being staged by participants of a global movement in Neo-Pentecostal evangelical Christianity called "Spiritual Mapping" or "Spiritual Warfare."3 In anticipation of the end time, its adherents are committed to "[taking] the whole gospel to the whole world" by "breaking the spiritual strongholds" (The Lausanne Movement, | + | This group was not acting alone. In communities throughout the [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]], Kālacakra-centered exorcisms and [[prayer]] events were being staged by participants of a global {{Wiki|movement}} in Neo-Pentecostal evangelical [[Christianity]] called "[[Spiritual]] Mapping" or "[[Spiritual]] Warfare."3 In anticipation of the end time, its {{Wiki|adherents}} are committed to "[taking] the whole {{Wiki|gospel}} to the whole [[world]]" by "breaking the [[spiritual]] strongholds" (The Lausanne {{Wiki|Movement}}, |

| − | 2011) of a hierarchy of invisible, demonic spirits that hold specific geographical centers and ethnic populations in their grip. Its leaders are considered apostles and prophets, gifted by God, and adept in the practice of locating these beings and using exorcism and other religious techniques to wage a | + | 2011) of a {{Wiki|hierarchy}} of {{Wiki|invisible}}, {{Wiki|demonic}} [[spirits]] that hold specific geographical centers and {{Wiki|ethnic}} populations in their [[grip]]. Its leaders are considered {{Wiki|apostles}} and {{Wiki|prophets}}, gifted by [[God]], and {{Wiki|adept}} in the practice of locating these [[beings]] and using [[exorcism]] and other [[religious]] [[techniques]] to wage a |

| − | territorial spiritual war against them. In the United States, some of their most visible adherents avowedly seek dominion over politics, business and culture in preparation for the end times and the return of Jesus (Fresh Air from WHYY, 4 August 2011). The movement came to the attention of the non- | + | territorial [[spiritual]] [[war]] against them. In the [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]], some of their most [[visible]] {{Wiki|adherents}} avowedly seek dominion over {{Wiki|politics}}, business and {{Wiki|culture}} in preparation for the end times and the return of {{Wiki|Jesus}} (Fresh [[Air]] from WHYY, 4 August 2011). The {{Wiki|movement}} came to the [[attention]] of the non- |

| − | Christian American media in 2008, when an African Pastor named Apostle Thomas Muthee visited America and prayed over vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin (Blumenthal, 2008), and more recently, when Presidential candidates Rick Perry (Posner, 2011) and Michele Bachmann (Lizza, 2011) affirmed their own affiliation. | + | [[Christian]] [[American]] media in 2008, when an African Pastor named Apostle Thomas Muthee visited [[America]] and prayed over vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin (Blumenthal, 2008), and more recently, when Presidential candidates Rick Perry (Posner, 2011) and Michele Bachmann (Lizza, 2011) [[affirmed]] their [[own]] affiliation. |

| − | Fig. 2: Dalai Lama ritually disassembling mandala. Photograph by Don Farber. Reproduced with permission. | + | Fig. 2: [[Dalai Lama]] [[ritually]] disassembling [[mandala]]. Photograph by Don Farber. Reproduced with permission. |

| − | Since the late 1990s, the Dalai Lama's "Kalachakra for World Peace" initiation has emerged as a central site where Tibetan Buddhism and its relationship to the West have | + | Since the late 1990s, the [[Dalai Lama's]] "[[Kalachakra]] for [[World Peace]]" [[initiation]] has emerged as a central site where [[Tibetan Buddhism]] and its relationship to the [[West]] have |

| − | 3 According to Holvast (2009), "spiritual mapping as a "movement" originated in the 1980s in Colorado Springs. He argues that, while it is no longer a formal "movement," it is a worldwide practice among multiple Evangelical denominations, with especial influence in sub-Sahara African and South American | + | 3 According to Holvast (2009), "[[spiritual]] mapping as a "{{Wiki|movement}}" originated in the 1980s in [[Colorado Springs]]. He argues that, while it is no longer a formal "{{Wiki|movement}}," it is a worldwide practice among multiple Evangelical denominations, with especial influence in sub-Sahara African and [[South]] [[American]] |

| − | Pentecostal and charismatic missions. Here, I use the term "movement" to denote a population that shares 1) a practical theology; 2) a corollary set of religious practices, and 3) a sense of community identity. In the United States, the practices of spiritual warfare and mapping have become identified with | + | Pentecostal and {{Wiki|charismatic}} missions. Here, I use the term "{{Wiki|movement}}" to denote a population that shares 1) a {{Wiki|practical}} {{Wiki|theology}}; 2) a corollary set of [[religious]] practices, and 3) a [[sense]] of {{Wiki|community}} [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]]. In the [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]], the practices of [[spiritual]] warfare and mapping have become identified with |

| − | the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR), headed by C. Peter Wagner, and so is again approaching "movement" status in Holfast's terms. For other cultural contexts, see Bernardi 1999; Jorgenson 2005; McAlister 2012a, 2012b. | + | the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR), headed by C. Peter Wagner, and so is again approaching "{{Wiki|movement}}" {{Wiki|status}} in Holfast's terms. For other {{Wiki|cultural}} contexts, see Bernardi 1999; Jorgenson 2005; McAlister 2012a, 2012b. |

| − | been imagined and acted upon by this segment of evangelical Christians. In Spiritual Warfare parlance, the Kālacakra is not only the key initiation rite into tantric or Tibetan Buddhism, it is the primary vehicle by which the current Dalai Lama prepares for the end times by seeking to transform America—and the world—into "a universal Buddhocracy" (Truthspeaker, 2011) called the Kingdom of Shambhala. Tibetan Buddhism is, in short, a missionary competitor for global religious domination.4 | + | been [[imagined]] and acted upon by this segment of evangelical [[Christians]]. In [[Spiritual]] Warfare parlance, the [[Kālacakra]] is not only the key [[initiation]] [[rite]] into [[tantric]] or [[Tibetan Buddhism]], it is the primary [[vehicle]] by which the current [[Dalai Lama]] prepares for the end times by seeking to [[transform]] America—and the world—into "a [[universal]] Buddhocracy" (Truthspeaker, 2011) called the [[Kingdom of Shambhala]]. [[Tibetan Buddhism]] is, in short, a {{Wiki|missionary}} competitor for global [[religious]] domination.4 |

| − | There are a number of analytics historians of Buddhism routinely use to make sense of Buddhist-Christian encounters such as this. We might, for example write our analysis as a chapter in the longer history of Buddhist Modernism in its American incarnations.5 Alternately, we might contextualize the | + | There are a number of analytics {{Wiki|historians}} of [[Buddhism]] routinely use to make [[sense]] of Buddhist-Christian encounters such as this. We might, for example write our analysis as a [[chapter]] in the longer history of [[Buddhist Modernism]] in its [[American]] incarnations.5 Alternately, we might contextualize the |

| − | "exorcism of the mandala" within the broader history of Christian imaginings about Tibetan Buddhism—perhaps analogize the contemporary Spiritual Mappers' reading to previous instances of Christian missionaries "finding" in Tibetan Buddhists a dark counter version of themselves. These perspectives have their place, and inform the following discussion. | + | "[[exorcism]] of the [[mandala]]" within the broader history of [[Christian]] imaginings about [[Tibetan]] Buddhism—perhaps analogize the contemporary [[Spiritual]] Mappers' reading to previous instances of {{Wiki|Christian missionaries}} "finding" in [[Tibetan Buddhists]] a dark counter version of themselves. These perspectives have their place, and inform the following [[discussion]]. |

| − | Yet the Tibetan-Evangelical encounter is more than another instance of strategic rhetoricizing or fantasizing by either of our protagonists. Its analysis opens a small yet compelling window into a larger study of how "globalization" shapes their shared experience. Over the last decades, the world has seen dramatic reconfigurations of social geography, marked by the growth of transplanetary or "supraterritorial" connections between various peoples (Scholte, 2005: 8). These connections, I argue at length elsewhere,6 palpably shape the content and reception of Tibetan Buddhist ritual in diaspora, and demand to be considered more fully than traditional analytics allow. | + | Yet the Tibetan-Evangelical encounter is more than another instance of strategic rhetoricizing or fantasizing by either of our protagonists. Its analysis opens a small yet compelling window into a larger study of how "globalization" shapes their shared [[experience]]. Over the last decades, the [[world]] has seen dramatic reconfigurations of {{Wiki|social}} {{Wiki|geography}}, marked by the growth of transplanetary or "supraterritorial" connections between various peoples (Scholte, 2005: 8). These connections, I argue at length elsewhere,6 palpably shape the content and {{Wiki|reception}} of [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[ritual]] in {{Wiki|diaspora}}, and demand to be considered more fully than [[traditional]] analytics allow. |

| − | Accordingly, I take a different approach. Here, I present the "exorcism of the mandala" as the by-product of the simultaneous globalizations of Tibetan | + | Accordingly, I take a different approach. Here, I {{Wiki|present}} the "[[exorcism]] of the [[mandala]]" as the by-product of the simultaneous globalizations of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] and Evangelicalism with the [[human rights]] [[discourse]] that emerged in late twentieth century [[America]]. I begin with a brief genealogy of the [[Kālacakra initiation]], highlighting its historical function as a [[vehicle]] by which [[Tibetans]] abroad have promoted models of [[Tibetan]] autonomy. Following its trail to the |

| + | |||

| + | [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]] in 1981, I argue that the association of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] and the "[[Kalachakra]] for [[World Peace]]" with [[human rights]] {{Wiki|politics}} in the 1980s was articulated with three {{Wiki|interrelated}} {{Wiki|processes}}: the globalization of [[Tibetan Buddhism]], the [[transformation]] of [[Tibetan]] [[nationalism]] into an international {{Wiki|movement}}, and the entry of [[Tibet]] and [[His Holiness the Dalai Lama]] into 'global {{Wiki|civil society}}.' It was this final process, I will suggest, that especially | ||

| + | |||

| + | attracted the [[attention]] of the [[Spiritual]] Mapping {{Wiki|movement}}, for whom global {{Wiki|civil society}} is largely {{Wiki|synonymous}} with liberal, anti-Christian {{Wiki|politics}} and policies. From this {{Wiki|perspective}}, I suggest that the "[[exorcism]] of the [[mandala]]" may be read as both by-product and critique of globalization, and so underscores the need for a thoughtful re-evaluation of long-standing [[Buddhist Studies]] analytics. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4 On [[Buddhisms]] as/and contemporary {{Wiki|missionary}} [[traditions]], see Learman 2005. 5 McMahan characterizes [[Buddhist Modernism]] as "an actual new [[form]] of [[Buddhism]] that is the result of [[modernization]], westernization, reinterpretation, image-making, revitalization, and reform..." (2008: p. 5). 6 Harrington and McAlister, forthcoming. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===[[The Kālacakra Tantra and the Globalization of Tibetan Buddhism]]=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The "[[Kalachakra]] for [[World Peace]]" [[initiation]] so inimical to [[Spiritual]] Mappers has its textual origins in the [[Kālacakra Tantra]] ("[[Wheel of Time]]"; Tib., dus kyi 'khor): an [[Indian Buddhist]] [[esoteric]] treatise belonging to the class of unexcelled [[yoga-tantras]] (Skt. Anuttara-yoga-tantra).7 Dating to the early decades of eleventh century C.E., the work is composed of five chapters that [[Tibetan tradition]] characterizes into [[three divisions]]: the [[Outer Kālacakra]] | ||

| − | + | (Tib. phyi'i dus 'khor), dealing with its unique [[cosmology]] and [[astrology]]; the [[Inner Kālacakra]] ([[nang]] gi dus 'khor), centering on [[human]] psychophysiology and embryology, and the Alternative [[Kālacakra]] ([[gzhan]] gyi dus 'khor), dedicated to the [[Kālacakra's]] particular [[six-limbed yoga]] practice. It is in this final | |

| + | [[division]] that we find reference to the requisite [[initiation]] into the practice by means of its sand mandala.8 | ||

| + | It is in the first two divisions of the [[Kālacakra Tantra]] that we find the textual source of the [[Spiritual]] Mapper's notion of [[Tibetan Buddhism's]] "end times," the [[Kālacakra's]] [[connection]] to a "Buddhocracy," and of the [[Dalai Lama's]] hidden commitment to warfare and [[world]] {{Wiki|domination}}. According to its first | ||

| − | + | [[chapter]], the [[Buddha]] [[taught]] the [[Kālacakra]] in [[India]] to [[King Sucandra]], the [[enlightened]] [[ruler]] of a vast [[hidden kingdom]] named [[Śambhala]]. There, the [[Kālacakra]] has been quietly preserved and propagated by a line of devout [[kings]] and [[kalkins]] (chieftains) to this very day. However, at the end of this world's current [[age of degeneration]], [[Śambhala]] and its [[Kālacakra teachings]] will rise to global prominence: a great [[war]] will erupt, and the twenty-fifth [[Kalkin]] of [[Śambhala]] will | |

| − | + | lead his armies in a triumphant {{Wiki|battle}} against hordes of [[barbarian]] invaders. This will usher in a new golden age, in which [[peace]], [[harmony]] and the [[dharma]] will flourish, and those affiliated with the [[Kālacakra tradition]] will be [[reborn]] in [[Śambhala]] to partake in its benefits: | |

| − | + | When eight [[Kalkins]] have reigned, the [[barbarian]] [[religion]] will certainly appear in the land of [[Mecca]]. Then, at the time of the [[wrathful]] [[Kalkin]] Cakrin and the | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | vicious [[barbarian]] lord, a fierce {{Wiki|battle}} will occur on [[earth]]. | |

| − | + | At the end of the age Cakrin, the [[universal]] [[emperor]], will come out from [[Kalāpa]], the city the [[gods]] built on Mount [[Kailāsa]]. He will attack the [[barbarians]] with his four-division {{Wiki|army}}… | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | [[Kalkin]], with [[Viṣṇu]] and [[Śiva]], will destroy the [[barbarians]] in {{Wiki|battle}} with his {{Wiki|army}}. Then Cakrin will return to his home in [[Kalāpa]], the city the [[gods]] built on Mount [[Kailāsa]]. At that time, everyone on [[earth]] will be fulfilled with [[religion]], [[pleasure]], and [[prosperity]]. Grain will grow in the wild, and [[trees]] will [[bow]] | ||

| − | + | with everlasting fruit—these things will occur. (Newman, 1995: 288–289) 7 According to its first [[chapter]], the [[existing]] version of the [[Kālacakra Tantra]] is an abridged version of a larger original [[Tantra]] entitled the [[Paramādibuddhatantra]], | |

| − | + | reportedly consisting of twelve thousand verses. Little of that work is extant. The version I refer to throughout as the [[Kālacakra Tantra]] is more formally | |

| − | entitled the Laghukālacakrarajatantra, and is comprised of approximately 1,050 verses. For Sanskrit and Tibetan edition, see Vira & Chandra, 1966. For discussion of the Tantra's textual history, see Wallace, 2001: 3–4; Newman, 1987. 8 The initiation and the sand mandala are referenced in the third | + | entitled the Laghukālacakrarajatantra, and is comprised of approximately 1,050 verses. For [[Sanskrit]] and [[Tibetan]] edition, see [[Vira]] & [[Chandra]], 1966. For [[discussion]] of the [[Tantra's]] textual history, see Wallace, 2001: 3–4; Newman, 1987. 8 The [[initiation]] and the [[sand mandala]] are referenced in the third |

| − | "Empowerment Chapter" (Skt. Abhi ṣ ekapa ṭ ala; Tib. mngon par dbang bskur ba). However, substantive explication of the mandala and the initiation are traditionally derived from commentaries, most notably the Vimalaprabhā. For Sanskrit edition, see Upādhyāya et al., 1986. | + | "[[Empowerment]] [[Chapter]]" (Skt. [[Abhi]] ṣ ekapa ṭ ala; Tib. mngon par [[dbang bskur]] ba). However, substantive explication of the [[mandala]] and the [[initiation]] are [[traditionally]] derived from commentaries, most notably the [[Vimalaprabhā]]. For [[Sanskrit]] edition, see [[Upādhyāya]] et al., 1986. |

| − | The root text however, does not stop there. In a substantial auto-commentary in the Kālacakra Tantra's second chapter (II.48–50), the composer(s) re-frame the routing of the barbarians.9 The war, they contend, is an allegory for the Kālacakra yogin's inner experience. It is the individual who is the | + | The [[root text]] however, does not stop there. In a substantial auto-commentary in the [[Kālacakra]] [[Tantra's]] second [[chapter]] (II.48–50), the composer(s) re-frame the routing of the barbarians.9 The [[war]], they contend, is an allegory for the [[Kālacakra]] [[yogin's]] inner [[experience]]. It is the {{Wiki|individual}} who is the |

| − | "battlefield" wherein "Kalki," the individual's correct knowledge, wages battle with the vicious king of the Barbarians, the path of non-virtue: | + | "battlefield" wherein "[[Kalki]]," the individual's [[correct knowledge]], wages {{Wiki|battle}} with the vicious [[king]] of the [[Barbarians]], the [[path]] of [[non-virtue]]: |

| − | Cakrin is adamantine mind in one's body; Kalkin is true gnosis…the demon army is the fourfold host of Death: malice, ill will, jealousy, and attachment and aversion. Their defeat in battle is the destruction of the terror of existence. Splendid victory is the path to liberation…Thus, the war with the barbarian | + | Cakrin is [[adamantine]] [[mind]] in one's [[body]]; [[Kalkin]] is true gnosis…the {{Wiki|demon}} {{Wiki|army}} is the fourfold host of [[Death]]: [[malice]], [[ill will]], [[jealousy]], and [[attachment]] and [[aversion]]. Their defeat in {{Wiki|battle}} is the destruction of the {{Wiki|terror}} of [[existence]]. Splendid victory is the [[path]] to liberation…Thus, the [[war]] with the [[barbarian]] |

| − | lord definitely occurs within a living being's body; but the illusory, external war with the barbarians in the land of Mecca is certainly not a war. (Newman, 1995: p. 289) | + | lord definitely occurs within a living being's [[body]]; but the [[illusory]], external [[war]] with the [[barbarians]] in the land of [[Mecca]] is certainly not a [[war]]. (Newman, 1995: p. 289) |

| − | In short, the routing of the barbarians symbolizes the victory of gnosis over ignorance. It is not an act of war, but "a mere magical show the Kalkin emanates to convert, not destroy, the Muslims" (Newman, 1995: 286). This interpretive emphasis on non-violence—on compassionate conversion over physical | + | In short, the routing of the [[barbarians]] [[symbolizes]] the victory of [[gnosis]] over [[ignorance]]. It is not an act of [[war]], but "a mere [[magical]] show the [[Kalkin]] [[emanates]] to convert, not destroy, the {{Wiki|Muslims}}" (Newman, 1995: 286). This interpretive {{Wiki|emphasis}} on non-violence—on [[compassionate]] [[conversion]] over [[physical]] |

| − | force—is one reason that, as in the current Dalai Lama's view, the Kālacakra and its Śambhala myth are understood to promote world peace. | + | force—is one [[reason]] that, as in the current [[Dalai Lama's]] view, the [[Kālacakra]] and its [[Śambhala]] [[myth]] are understood to promote [[world peace]]. |

| − | The Kālacakra and its richly interpretable Śambhala narrative were transmitted from India to Tibet in the eleventh century. It gained particular prominence | + | The [[Kālacakra]] and its richly interpretable [[Śambhala]] {{Wiki|narrative}} were transmitted from [[India]] to [[Tibet]] in the eleventh century. It gained particular prominence |

| − | in the late thirteenth and fourteenth century when Tibet was under Mongol rule,10 and from that time forwards was disseminated and practiced within the Sakya, Kagyu, and Jonang traditions. By the sixteenth century however, the Kālacakra was especially identified with Geluk tradition, in part because | + | in the late thirteenth and fourteenth century when [[Tibet]] was under {{Wiki|Mongol}} rule,10 and from that time forwards was disseminated and practiced within the [[Sakya]], [[Kagyu]], and [[Jonang traditions]]. By the sixteenth century however, the [[Kālacakra]] was especially identified with [[Geluk tradition]], in part because |

| − | several Panchen Lamas and Dalai Lamas gave public Kālacakra teachings and initiations—a notable departure from general Tantric practice, in which initiations are usually restricted to a select group of initiates.11 | + | several [[Panchen Lamas]] and [[Dalai Lamas]] gave public [[Kālacakra teachings]] and initiations—a notable departure from general [[Tantric practice]], in which [[initiations]] are usually restricted to a select group of initiates.11 |

| − | Significantly, Geluk masters publically disseminated the Kālacakra outside of Tibet proper. Between 1925 and 1932, the ninth Panchen Lama repeatedly transmitted Śambhala prayers and gave Kālacakra initiations in large public rituals in Inner Mongolia and China.12 In 1932, he travelled to Beijing's Forbidden City and gave the Kālacakra initiation to an audience of more than 100,000 people from the "Hall of Great Peace"—an | + | Significantly, [[Geluk]] [[masters]] publically disseminated the [[Kālacakra]] outside of [[Tibet]] proper. Between 1925 and 1932, the ninth [[Panchen Lama]] repeatedly transmitted [[Śambhala]] [[prayers]] and gave [[Kālacakra initiations]] in large public [[rituals]] in [[Inner Mongolia]] and China.12 In 1932, he travelled to [[Beijing's]] Forbidden City and gave the [[Kālacakra initiation]] to an audience of more than 100,000 [[people]] from the "Hall of Great Peace"—an |

| − | 9 For a more general discussion of the commentarial strategies of the Kālacakra tradition, see Broido, 1988. 10 Central to its popularization at this time were the works of the Jonang master Dolpopa (Dol po pa Shes rab Rgyal mtshan, 1292–1361), who ordered a revised translation of both the root text and its | + | 9 For a more general [[discussion]] of the {{Wiki|commentarial}} strategies of the [[Kālacakra tradition]], see Broido, 1988. 10 Central to its popularization at this time were the works of the [[Jonang]] [[master]] [[Dolpopa]] ([[Dol po pa]] [[Shes rab]] [[Rgyal mtshan]], 1292–1361), who ordered a revised translation of both the [[root text]] and its |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | primary commentary, and the contemporaneous [[Sakya master]] Buton ([[Bu ston]] [[Rin chen]] Grub, 1290–1363), who annotated and wrote extensively on the [[Tantra]]. 11 [[Edward Henning]] has suggested that [[Dolpopa]] was the first [[master]] to [[conceive]] of the [[idea]] of giving the [[Kālacakra initiation]] as a public event. See Gyatso & | |

| − | + | Kilty, 2004: 3. 12 The ninth [[Panchen Lama]], [[Losang]] [[Thubten Choekyi Nyima]] (Blo [[sangs]] Thub bstan [[Chos kyi]] [[Nyi ma]], 1883–1937) fled to [[China]] in 1924 in search of outside support for his bid to maintain a local {{Wiki|rule}}, {{Wiki|independent}} of the central [[Tibetan government]]. There, he was welcomed by a Nationalist government | |

| + | intent upon incorporating a {{Wiki|de facto}} {{Wiki|independent}} [[Tibet]] and [[Mongolia]] by re-framing [[Buddhism]] as a unified pan-Asian [[religion]]; a single [[tree]] with multiple, peacefully-coexisting {{Wiki|ethnic}} branches, growing in the soil of the {{Wiki|modern}} {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|nation}} [[state]]. See Tuttle, 2007: 68 ff. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | event punctuated by the construction of the [[Kālacakra]] [[sand mandala]], there dubbed the "[[Peace]] [[Mandala]] of [[Shambhala]]." Two years later, he [[offered]] a [[Kālacakra initiation]] in {{Wiki|Hangzhou}}, where he "prayed for [[world peace]]" and [[initiated]] an audience of up to 70,000 into the [[Kālacakra tradition]]. These gatherings | |

| − | + | furthered his efforts to advocate for a [[Tibetan]] [[vision]] of governance, characterized by a [[peaceful]] merging of [[religion]] and {{Wiki|politics}} ([[chos]] srid [[zung]] 'grel) (Tuttle, 2008: 313, 318 ff; Tuttle, 2005: 227). In short, the [[Kālacakra initiation]] was a [[vehicle]] used by [[Tibetans]] abroad to promote a [[vision]] of [[Tibetan]] autonomy (Tuttle, 2007: 171; Tuttle, 2005: 212). It would reprise this role a half century later when [[Tibetan Buddhism]] came [[west]]. | |

| − | in Exile: Tenzin Gyatso, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. | + | The [[Kālacakra initiation]] came to the [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]] as part of the larger globalization of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] that followed [[China's]] {{Wiki|occupation}} of [[Tibet]] in 1951, and the subsequent {{Wiki|diaspora}} of hundreds of thousands of [[Tibetans]] after 1959. In the 1960s and 70s, a growing number of [[Tibetan lamas]] came to [[America]] and established [[dharma]] centers.13 In 1979, however, [[America]] was visited by a [[Geluk]] [[lama]] who was both a [[Kālacakra]] [[master]] and head of the [[Tibetan Government in Exile]]: [[Tenzin Gyatso]], [[His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama]]. |

| − | The Dalai Lama's dual identity as religious and political authority would become central to the characterization of Tibetan Buddhism by the Spiritual Mapping movement. It also framed his early activities in Euro-America. In his capacity as head of the Tibetan Government in Exile, the Dalai Lama traveled | + | The [[Dalai Lama's]] dual [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] as [[religious]] and {{Wiki|political}} authority would become central to the characterization of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] by the [[Spiritual]] Mapping {{Wiki|movement}}. It also framed his early [[activities]] in Euro-America. In his capacity as head of the [[Tibetan Government in Exile]], the [[Dalai Lama]] traveled |

| − | and lectured widely over the next decade to raise public awareness of Tibet's political situation, and to advocate for Tibetan freedom. In his role as Buddhist scholar and ritual specialist, His Holiness gave teachings on Tibetan Buddhism and offered public rituals. These latter events were an occasion for His Holiness to explicate his decidedly globalized vision of Tibetan Buddhism. In academic circles, this is sometimes characterized as a form of | + | and lectured widely over the next decade to raise public [[awareness]] of [[Tibet's]] {{Wiki|political}} situation, and to advocate for [[Tibetan]] freedom. In his role as [[Buddhist scholar]] and [[ritual]] specialist, [[His Holiness]] gave teachings on [[Tibetan Buddhism]] and [[offered]] public [[rituals]]. These [[latter]] events were an occasion for [[His Holiness]] to explicate his decidedly globalized [[vision]] of [[Tibetan Buddhism]]. In {{Wiki|academic}} circles, this is sometimes characterized as a [[form]] of |

| − | "Buddhist Modernism" insofar as it highlights Tibetan Buddhism's respect for reason and experience; its compatibility with democracy and modern science; its commitment to interfaith dialogue and rejection of religious conversion movements.14 | + | "[[Buddhist Modernism]]" insofar as it highlights [[Tibetan Buddhism's]] [[respect]] for [[reason]] and [[experience]]; its compatibility with {{Wiki|democracy}} and {{Wiki|modern science}}; its commitment to interfaith {{Wiki|dialogue}} and rejection of [[religious]] [[conversion]] movements.14 |

| − | For our purposes, the most salient feature of His Holiness' vision was its dual emphasis on global social engagement and world peace. His Holiness drew from the Buddhist notion of compassion—a "universal human responsibility"—to promote a secular ethics grounded on non-violence that could serve as a tool | + | For our purposes, the most salient feature of [[His Holiness]]' [[vision]] was its dual {{Wiki|emphasis}} on global {{Wiki|social}} engagement and [[world peace]]. [[His Holiness]] drew from the [[Buddhist]] notion of compassion—a "[[universal]] [[human]] responsibility"—to promote a {{Wiki|secular}} [[ethics]] grounded on [[non-violence]] that could serve as a tool |

| − | for global social transformation. Such an ethic presumed a supra-territorial vision of humanity – one that subsumed familial or national identity to a global one. Its cultivation was, in turn, intrinsic to the development of world peace. "Internal peace," he explained "is an essential first step to achieving peace in the world, true and lasting peace." How does one cultivate it? | + | for global {{Wiki|social}} [[transformation]]. Such an [[ethic]] presumed a supra-territorial [[vision]] of [[humanity]] – one that subsumed familial or national [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] to a global one. Its [[cultivation]] was, in turn, intrinsic to the [[development]] of [[world peace]]. "Internal [[peace]]," he explained "is an [[essential]] first step to achieving [[peace]] in the [[world]], true and lasting [[peace]]." How does one cultivate it? |

| − | 13 Among the most famous lineage holders that came to the West in the 1970s are the Kagyu (bKa' brgyud) teacher Kalu Rimpoche (1975); the Nyigma (rNying-ma) Dujom Rimpoche(1972); Sakya Trizin Rinpoche (1974); and the Gyalwa Karmapa, head of the Karma bKa' brgyud school (1974). By 1987, there were approximately 180 Tibetan Tantric centers in North America alone. By 1997, that number has more than doubled. See Cabezon, 2006: 98-95; Batchelor, 1994: chapter 8. 14 On the Dalai Lama and Tibetan Buddhism in the West as Buddhist Modernist, see Lopez, 1999: 185 ff. For a critique of Lopez' characterization, see Dreyfus, 2005: 4 ff. | + | 13 Among the most famous [[lineage holders]] that came to the [[West]] in the 1970s are the [[Kagyu]] ([[bKa' brgyud]]) [[teacher]] Kalu [[Rimpoche]] (1975); the [[Nyigma]] ([[rNying-ma]]) Dujom Rimpoche(1972); [[Sakya Trizin]] [[Rinpoche]] (1974); and the [[Gyalwa Karmapa]], head of the [[Karma bKa' brgyud]] school (1974). By 1987, there were approximately 180 [[Tibetan]] [[Tantric]] centers in [[North America]] alone. By 1997, that number has more than doubled. See [[Cabezon]], 2006: 98-95; [[Batchelor]], 1994: [[chapter]] 8. 14 On the [[Dalai Lama]] and [[Tibetan Buddhism]] in the [[West]] as [[Buddhist]] Modernist, see [[Lopez]], 1999: 185 ff. For a critique of [[Lopez]]' characterization, see [[Dreyfus]], 2005: 4 ff. |

| − | It's very simple. In the first place, by realising clearly that all mankind is one, that human beings in every country are members of one and the same family. In other words, all these quarrels between countries and blocs are family quarrels and should not go beyond certain limits. Just as there can be | + | It's very simple. In the first place, by realising clearly that all mankind is one, that [[human beings]] in every country are members of one and the same [[family]]. In other words, all these quarrels between countries and blocs are [[family]] quarrels and should not go beyond certain limits. Just as there can be |

| − | friction, disputes between man and wife in a union, but within specific limits, as each party knows deep down in the heart that they are bound together by a far more important sentiment. Next, it is important to grasp the real meaning of this brotherhood based on love and | + | friction, [[disputes]] between man and wife in a union, but within specific limits, as each party [[knows]] deep down in the [[heart]] that they are [[bound]] together by a far more important sentiment. Next, it is important to [[grasp]] the real meaning of this brotherhood based on [[love]] and [[kindness]]…. (Cited in Mills, 2009: 197) |

| − | These emphases on global engagement and world peace would come to infuse the ideological backdrop of the nine Western-based public initiations into Kālacakra practice.15 His Holiness offered the first in 1981 to an audience of a few hundred in Deer Park Center, Wisconsin. Over its three-day period, its | + | These emphases on global engagement and [[world peace]] would come to infuse the {{Wiki|ideological}} backdrop of the nine Western-based public [[initiations]] into [[Kālacakra]] practice.15 [[His Holiness]] [[offered]] the first in 1981 to an audience of a few hundred in [[Deer Park]] [[Center]], [[Wisconsin]]. Over its three-day period, its |

| − | Western initiates learned that "[t]he Kalachakra has a special connection with all the people of the planet" but most particularly "with one land on this | + | [[Western]] [[initiates]] learned that "[t]he [[Kalachakra]] has a special [[connection]] with all the [[people]] of the {{Wiki|planet}}" but most particularly "with one land on this [[earth]]… [[Shambhala]]," where the [[Tantra]] had been preserved and propagated since the time of the [[Buddha]]" (Bstan-ʾdzin-rgya-mtsho, 1981).16 In 1985, a crowd of |

| − | thousands gathered in Rinkon, Switzerland to attend an event explicitly billed as "The Kalachakra Initiation for World Peace," and featuring the now ubiquitous Kālacakra sand mandala. His Holiness pointedly highlighted a "special connection" between the Tantra, Śambhala, and this world, and "the special | + | thousands [[gathered]] in Rinkon, [[Switzerland]] to attend an event explicitly billed as "The [[Kalachakra Initiation]] for [[World Peace]]," and featuring the now {{Wiki|ubiquitous}} [[Kālacakra]] [[sand mandala]]. [[His Holiness]] pointedly highlighted a "special [[connection]]" between the [[Tantra]], [[Śambhala]], and this [[world]], and "the special |

| − | significance of the initiation as a powerful force for the realization and preservation of world peace in this present time. Through participating in the initiation we ourselves can become vehicles for the peace-creating energies contained in this teaching."(n.a., 1985) | + | significance of the [[initiation]] as a powerful force for the [[realization]] and preservation of [[world peace]] in this {{Wiki|present}} time. Through participating in the [[initiation]] we ourselves can become vehicles for the peace-creating energies contained in this teaching."(n.a., 1985) |

| − | In the summer of 1989, when His Holiness offered the third Western-based Kālacakra initiation to an audience of more than three thousand participants in Los Angeles California, the vision of a free Tibet as a "Zone of Peace" that he had presented to a U. S Congressional Human Rights Caucus had been | + | In the summer of 1989, when [[His Holiness]] [[offered]] the third Western-based [[Kālacakra initiation]] to an audience of more than three thousand participants in [[Los Angeles]] [[California]], the [[vision]] of a free [[Tibet]] as a "Zone of [[Peace]]" that he had presented to a U. S Congressional [[Human Rights]] Caucus had been |

| − | circulating in Tibet-centered communities and web sites for two years.17 Inevitably, a "Free Tibet" as a "Zone of Peace" and the legendary land of Shambhala were increasingly associated in the imagination of its American initiates. This connection was re-enforced in 1991 when His Holiness conferred the "Kalachakra for World Peace" to four thousand people in Madison Square Garden's Paramount Theater, and in 1999 when the "Kalachakra for World Peace" | + | circulating in Tibet-centered communities and web sites for two years.17 Inevitably, a "{{Wiki|Free Tibet}}" as a "Zone of [[Peace]]" and the legendary land of [[Shambhala]] were increasingly associated in the [[imagination]] of its [[American]] [[initiates]]. This [[connection]] was re-enforced in 1991 when [[His Holiness]] conferred the "[[Kalachakra]] for [[World Peace]]" to four thousand [[people]] in [[Madison]] [[Square]] Garden's [[Paramount]] Theater, and in 1999 when the "[[Kalachakra]] for [[World Peace]]" |

| − | 15 It should be noted that His Holiness' Kālacakra initiations were not limited to North America. These rituals have been no less important to the building of a pan-Tibetan identity in exile, and to sustaining positive relations with culturally Tibetan residents of the Himalayan borderlands. 16 This was not | + | 15 It should be noted that [[His Holiness]]' [[Kālacakra initiations]] were not limited to [[North America]]. These [[rituals]] have been no less important to the building of a pan-Tibetan [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] in exile, and to sustaining positive relations with culturally [[Tibetan]] residents of the [[Himalayan]] borderlands. 16 This was not |

| + | |||

| + | the first time Euro-American audiences had learned about this association of [[Shambhala]]: [[Madame Blavatsky]] (1831–1891) and [[Nicholas Roerich]] (1874–1947) had promulgated a comparable [[vision]]. 17 "The [[Tibetan people]] are eager to contribute to regional and [[world peace]], and I believe they are in a unique position | ||

| − | + | to do so. [[Traditionally]], [[Tibetans]] are a [[peace]] [[loving]] and non-violent [[people]]. Since [[Buddhism]] was introduced to [[Tibet]] over one thousand years ago, [[Tibetans]] have practiced [[non-violence]] with [[respect]] to all [[forms]] of [[life]]… But for [[China's]] {{Wiki|occupation}}, [[Tibet]] would still, today, fulfill its natural role as a buffer | |

| − | + | [[state]] maintaining and promoting [[peace]] in {{Wiki|Asia}}. It is my {{Wiki|sincere}} [[desire]], as well as that of the [[Tibetan people]], to restore to [[Tibet]] her invaluable role, by converting the entire country—comprising the three provinces of [[U-Tsang]], [[Kham]] and Amdo—once more into a place of stability, [[peace]] and [[harmony]]. In the best of [[Buddhist tradition]], [[Tibet]] would extend its services and [[hospitality]] to all who further the [[cause]] of [[world peace]] and the well-being of mankind and the natural {{Wiki|environment}} we share." (T. Gyatso, 1987) | |

| − | |||

| + | travelled to [[Bloomington]], [[Indiana]]. By 2004, when our [[Spiritual]] [[Warriors]] were [[gathering]] on the banks of Lake [[Ontario]] to combat the [[mandala]] "[[spirits]]," the [[Dalai Lama's]] [[Kālacakra initiation]] had been associated in contemporary popular [[American]] [[thought]] with [[world peace]] and [[Tibetan]] [[nationalism]] for almost two decades. | ||

| − | |||

| + | ===[[Human Rights Politics: Globalizing Sovereignty]]=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | It was not only Tibetan Buddhism that was being globalized during this time. As the basic civil and political rights under contention in America were projected onto the global landscape, the United States had seen the emergence of a newly global discourse of human rights; a shift in concern for the | + | It was not only [[Tibetan Buddhism]] that was being globalized during this time. As the basic civil and {{Wiki|political}} rights under contention in [[America]] were {{Wiki|projected}} onto the global landscape, the [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]] had seen the [[emergence]] of a newly global [[discourse]] of [[human rights]]; a shift in [[concern]] for the |

| − | sovereignty of the people (Sassen, 1996) to "the inherent dignity and the equal and inalienable rights of the members of the human family."18 By 1977, this trend was formalized in the idea of "third generation rights" – those associated with such rights as a right to national self-determination, a clean environment and, significantly, the rights of indigenous minorities.19 Thus it was that by the 1980s, when the Dalai Lama began to travel around the West | + | {{Wiki|sovereignty}} of the [[people]] (Sassen, 1996) to "the [[inherent]] [[dignity]] and the {{Wiki|equal}} and inalienable rights of the members of the [[human]] family."18 By 1977, this trend was formalized in the [[idea]] of "third generation rights" – those associated with such rights as a right to national [[self-determination]], a clean {{Wiki|environment}} and, significantly, the rights of indigenous minorities.19 Thus it was that by the 1980s, when the [[Dalai Lama]] began to travel around the [[West]] |

| − | to advocate for Tibetan freedom, this vision of human and minority rights had assumed its stature as the ultimate moral arbiter of international conduct. | + | to advocate for [[Tibetan]] freedom, this [[vision]] of [[human]] and minority rights had assumed its stature as the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] [[moral]] arbiter of international conduct. |

| − | This discursive shift took institutional form in an explosion of trans-national networks. American activists, working with partners around the world, had | + | This discursive shift took institutional [[form]] in an explosion of trans-national networks. [[American]] activists, working with partners around the [[world]], had |

| − | devised ways to collect accurate accounts of some of the vilest behavior on earth that no one had bothered to document before. They invented ways to move this information to wherever activists had some chance to shame and pressure the perpetrators. Theirs was a politics of the global flow of key bits of fact (Cmiel, 1999: 1232).20 | + | devised ways to collect accurate accounts of some of the vilest {{Wiki|behavior}} on [[earth]] that no one had bothered to document before. They invented ways to move this [[information]] to wherever activists had some chance to [[shame]] and pressure the perpetrators. Theirs was a {{Wiki|politics}} of the global flow of key bits of fact (Cmiel, 1999: 1232).20 |

| − | These networks were formalized in a vast assemblage of non-governmental organizations that saw themselves as a "global civil society" dedicated to a range of progressive social and economic projects: the establishment of more equitable relations between the global North and South, the protection of global environments, women's issues and, of course, human rights. Global civil society thus challenged the claims of market globalism and its | + | These networks were formalized in a vast assemblage of non-governmental organizations that saw themselves as a "global {{Wiki|civil society}}" dedicated to a range of progressive {{Wiki|social}} and economic projects: the establishment of more equitable relations between the global [[North]] and [[South]], the [[protection]] of global environments, women's issues and, of course, [[human rights]]. Global {{Wiki|civil society}} thus challenged the claims of market globalism and its |

| − | 18 Here, I am drawing on the language of the preamble to The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) adopted by the UN General Assembly on December 10, 1948. Despite this mid-century pedigree, it is clear that the contemporary human rights movement only took off in the 1970s. See Moyn, 2010:200; Cmiel, | + | 18 Here, I am drawing on the [[language]] of the preamble to The [[Universal]] Declaration of [[Human Rights]] (UDHR) adopted by the UN General Assembly on December 10, 1948. Despite this mid-century pedigree, it is clear that the contemporary [[human rights]] {{Wiki|movement}} only took off in the 1970s. See Moyn, 2010:200; Cmiel, |

| − | 2004; Cushman, 2011. 19 The concept of so-called "third-generation human rights" is associated with French jurist Karel Vasak, former director of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)'s Division of Human Rights and Peace. In November 1977 at UNESCO, in a speech | + | 2004; Cushman, 2011. 19 The {{Wiki|concept}} of so-called "third-generation [[human rights]]" is associated with {{Wiki|French}} jurist Karel Vasak, former director of the {{Wiki|United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization}} (UNESCO)'s [[Division]] of [[Human Rights]] and [[Peace]]. In November 1977 at [[UNESCO]], in a {{Wiki|speech}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | + | commemorating the thirtieth anniversary of the passing of the [[Universal]] Declaration of [[Human Rights]], Vasak summarized the [[development]] of international [[human rights]] and made first mention of the {{Wiki|concept}} of third-generation [[human rights]]. He pointed out that third-generation [[human rights]] are those born to |

| − | + | the obvious brotherhood of men and their indispensable solidarity, and provide that "everyone is entitled to a {{Wiki|social}} and international order in which the rights set forth in this Declaration can be fully [[realized]]" (Vasak, 1977: 29). 20 The [[human rights]] {{Wiki|movement}} was, in this [[sense]], co-emergent with what | |

| + | Manuel Castells calls "the rise of the network [[society]]" where "the key {{Wiki|social}} structures and [[activities]] are organized around electronically processed [[information]] networks" (Castells, 2001). | ||

| − | |||

| − | International was arguably the most influential member of the human rights NGOs. It was however, only one of more than two hundred groups working on human rights in the United States by the end of the seventies.21 | + | neoliberal underpinnings. For these "justice globalists" (Steger, 2008), "another [[world]] is possible:" a "new [[world]] order based on a global redistribution of [[wealth]] and a "non-violent {{Wiki|social}} resistance to the process of dehumanization the [[world]] is undergoing..." ([[World]] {{Wiki|Social}} Forum, 2002). [[Amnesty International]] was arguably the most influential member of the [[human rights]] NGOs. It was however, only one of more than two hundred groups working on [[human rights]] in the [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]] by the end of the seventies.21 |

| − | This backdrop had important consequences for Tibetan Buddhism and for the later Spiritual Warfare critique of the Kālacakra initiation. The Dalai Lama's unceasing advocacy of a peaceful resolution to Tibet's political situation—and by extension, to the suffering of all members of the human family – helped | + | This backdrop had important {{Wiki|consequences}} for [[Tibetan Buddhism]] and for the later [[Spiritual]] Warfare critique of the [[Kālacakra initiation]]. The [[Dalai Lama's]] unceasing advocacy of a [[peaceful]] resolution to [[Tibet's]] {{Wiki|political}} situation—and by extension, to the [[suffering]] of all members of the [[human]] [[family]] – helped |

| − | re-frame Tibetan Buddhism into an engaged Buddhism—a form of "justice globalism"—and his well-known notion of "universal human responsibility" as an | + | re-frame [[Tibetan Buddhism]] into an engaged Buddhism—a [[form]] of "justice globalism"—and his well-known notion of "[[universal]] [[human]] {{Wiki|responsibility}}" as an |

| − | iteration of "universal human rights."22 This latter association was galvanized in early 1987, when Roberta Cohen, formerly Carter's advisor on human rights, called for the human rights principle to be applied to the People's Republic of China (Cohen, 1987: 451). At about that time, the exiled leaders of the Tibetan Government in exile decided that the main principle to which the Dalai Lama would appeal in his foreign speeches would be the principle of human rights (Barnett, 2001: 310). | + | iteration of "[[universal]] [[human]] rights."22 This [[latter]] association was galvanized in early 1987, when Roberta Cohen, formerly Carter's advisor on [[human rights]], called for the [[human rights]] [[principle]] to be applied to the [[People's Republic of China]] (Cohen, 1987: 451). At about that time, the exiled leaders of the {{Wiki|Tibetan Government in exile}} decided that the main [[principle]] to which the [[Dalai Lama]] would appeal in his foreign speeches would be the [[principle]] of [[human rights]] (Barnett, 2001: 310). |

| − | Within a year, "Tibet" was formally inducted into global civil society. Human Rights Watch in New York published its first reports dedicated to Tibet in 1988. Amnesty International followed soon after. The Tibet Information Network (TIN) was officially constituted in London in 1988 as a non-political | + | Within a year, "[[Tibet]]" was formally inducted into global {{Wiki|civil society}}. [[Human Rights Watch]] in [[New York]] published its first reports dedicated to [[Tibet]] in 1988. [[Amnesty International]] followed soon after. The [[Tibet]] [[Information]] Network (TIN) was officially constituted in [[London]] in 1988 as a non-political |

| − | research body. The Tibetan Government in Exile set up a Human Rights Desk within its Department of Information and International Relations (Barnett, 2001: 310). In 1989, this entry yielded what many supporters considered to be a long-overdue result: His Holiness was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for "peaceful | + | research [[body]]. The [[Tibetan Government in Exile]] set up a [[Human Rights]] Desk within its Department of [[Information]] and International Relations (Barnett, 2001: 310). In 1989, this entry yielded what many supporters considered to be a long-overdue result: [[His Holiness]] was awarded the [[Nobel Peace Prize]] for "[[peaceful]] |

| − | solutions based upon tolerance and mutual respect in order to preserve the historical and cultural heritage of his people."23 | + | solutions based upon [[tolerance]] and mutual [[respect]] in order to preserve the historical and {{Wiki|cultural}} heritage of his people."23 |

| − | For Spiritual Mappers, however, the Dalai Lama's award would come to epitomize the hypocrisy of liberal thought, and the invidious workings of the Kālacakra initiation. To appreciate these concerns, let us turn to the roots and logic of the Spiritual Mapping | + | For [[Spiritual]] Mappers, however, the [[Dalai Lama's]] award would come to epitomize the {{Wiki|hypocrisy}} of liberal [[thought]], and the invidious workings of the [[Kālacakra initiation]]. To appreciate these concerns, let us turn to the [[roots]] and [[logic]] of the [[Spiritual]] Mapping |

| − | 21 For example, the Ford Foundation began funding human rights work in 1973; the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights dates itself to 1975. Human Rights Watch opened in 1978. 22 "We must complement the human rights ideal by developing a widespread practice of universal human responsibility," he said. "This | + | 21 For example, the Ford Foundation began funding [[human rights]] work in 1973; the Lawyers Committee for [[Human Rights]] dates itself to 1975. [[Human Rights Watch]] opened in 1978. 22 "We must complement the [[human rights]] {{Wiki|ideal}} by developing a widespread practice of [[universal]] [[human]] {{Wiki|responsibility}}," he said. "This |

| − | is not a religious matter. It arises from what I call the 'Common Human Religion'—that of love, the will to others' happiness, and compassion, the will to others' freedom from | + | is not a [[religious]] {{Wiki|matter}}. It arises from what I call the 'Common [[Human]] Religion'—that of [[love]], the will to others' [[happiness]], and [[compassion]], the will to others' freedom from [[suffering]]…." Cited in Fields, 1992: 379. 23 It should be noted that this [[concern]] with [[human rights]] was also playing out [[in Tibet]] |

| − | proper. Ron Schwartz notes that "posters and pamphlets appearing around Lhasa from the autumn of 1988 onwards increasingly stress the theme of human rights ("gro ba mi'I thob thang"). Tibetans described their protests not merely as a struggle for democracy and independence, but as a fight for human rights. The | + | proper. Ron Schwartz notes that "posters and pamphlets appearing around [[Lhasa]] from the autumn of 1988 onwards increasingly [[stress]] the theme of [[human rights]] ("gro ba mi'I [[thob thang]]"). [[Tibetans]] described their protests not merely as a struggle for {{Wiki|democracy}} and {{Wiki|independence}}, but as a fight for [[human rights]]. The |

| − | continuing flow of information from the outside world on democracy, human rights and other national struggles has provided Tibetans with an alternate point of reference, and an alternative vocabulary, to the Chinese. Thus they have come to regard their own struggle against Chinese rule in Tibet as representative of a contemporary worldwide movement. See Schwartz, 1994: 128. movement. | + | continuing flow of [[information]] from the outside [[world]] on {{Wiki|democracy}}, [[human rights]] and other national struggles has provided [[Tibetans]] with an alternate point of reference, and an alternative vocabulary, to the {{Wiki|Chinese}}. Thus they have come to regard their [[own]] struggle against {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|rule}} [[in Tibet]] as representative of a contemporary worldwide {{Wiki|movement}}. See Schwartz, 1994: 128. {{Wiki|movement}}. |

| + | ===[[Spiritual Mapping in the U.S.A]]=== | ||

| − | |||

| + | ===[[Globalizing Pentecostalism]]=== | ||

| − | |||

| + | Three months before [[His Holiness]] flew to {{Wiki|Stockholm}} to accept the 1989 [[Peace]] Prize, 4,400 [[Christians]] from 173 countries traveled to Manila to attend the Second International Congress on [[World]] Evangelization, often called Lausanne II.24 This [[gathering]] lasted for ten days and presented a range of {{Wiki|missionary}} | ||

| − | + | strategies and theories in support of the conference's stated {{Wiki|purpose}}: "to focus the whole {{Wiki|church}} of {{Wiki|Jesus Christ}} in a fresh way on the task of taking the whole {{Wiki|gospel}} to the whole [[world]]" (The Lausanne {{Wiki|Movement}}, 2011). It was here that "[[spiritual]] warfare" and "[[spiritual]] mapping" were put firmly on the international Evangelical {{Wiki|missionary}} agenda, and the [[seeds]] planted for its {{Wiki|modern}} {{Wiki|demonization}} of the [[Kālacakra Tantra]] (Holvast, 2009: 60). | |

| − | |||

| + | Lausanne II was in part an outgrowth of "{{Wiki|Church}} Growth," an Evangelical {{Wiki|movement}} that seeks to improve the effectiveness of its efforts by integrating detailed {{Wiki|sociological}} [[information]] about target populations into its {{Wiki|missionary}} strategies. It gained considerable momentum from the [[information]] explosion | ||

| − | + | that swept [[America]] from the 1970s; as such, {{Wiki|Church}} Growth—and as we will see, the [[Spiritual]] Mapping movement—was every bit as much "a {{Wiki|politics}} of the global flow of key bits of fact" as was the contemporaneous [[human rights]] movement.25 | |

| − | |||

| + | The [[Spiritual]] Warfare/Spiritual Mapping model presented at Lausanne II extended {{Wiki|Church}} Growth [[logic]] and practice. The [[Spiritual]] Mappers at Lausanne II | ||

| − | + | concurred that {{Wiki|sociological}} {{Wiki|data}} was important to successful evangelization; it was however, incomplete. The [[visible]] [[world]] also has an unseen [[supernatural]] [[dimension]] outside the purview of {{Wiki|sociological}} research: a {{Wiki|hierarchy}} of [[spirits]] that serve under the [[leadership]] of [[Satan]] (McAlister, 2012: 15–18; Holvast, | |

| − | + | 2009: [[chapter]] 3). In these end times—determined to be the 1990s – [[God]] has given a unique strategy to "break their domain," namely [[spiritual]] mapping. The {{Wiki|demons}} needed to be researched, identified and {{Wiki|physically}} located—literally "[[spiritually]] mapped"—and then exorcised by {{Wiki|apostles}} who channeled the {{Wiki|Holy}} | |

| − | + | [[Spirit]]. This would be a global [[effort]] whose central focus would be the "Resistance Belt": a band stretching across the eastern {{Wiki|hemisphere}} whose inhabitants are primarily non-Christian and most resistant to evangelization. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | 24 This timing reminds us that in the [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]], [[human rights]] [[discourse]] and the explosion of {{Wiki|Protestant}} evangelical {{Wiki|political}} [[activity]] entered into the {{Wiki|mainstream}} almost simultaneously. Recent {{Wiki|scholarship}} has suggested that it was the 1977 inauguration {{Wiki|speech}} of [[President]] Jimmy Carter—whose election | |

| − | + | prompted Time Magazine to dub 1976 the "Year of the Evangelical"—that placed "[[human rights]]" before the [[American]] public for the first time. 25 While the [[Spiritual]] Mapping {{Wiki|movement}} is profitably contextualized within the broader politicization of [[American]] evangelicalism that began under the Carter | |

| − | + | administration, it should not be conflated with contemporaneous evangelical efforts that self-consciously organize themselves as [[human rights]] themes. For more on these, see Castelli, 2004: [[chapter]] 6; Castelli, 2007. Similarly, the weakening of the [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Cold War}} [[enmity]] between the Eastern Bloc and the | |

| − | + | [[West]] altered the {{Wiki|political}} and global [[visions]] of many US evangelicals. Zoe Knox notes for many evangelicals and especially for SW practitioners, Islam—and the conflicts surrounding {{Wiki|Israel}} and the Middle East—filled the slot once occupied by the {{Wiki|Soviet Union}}. (Knox, 2011) | |

| − | |||

| + | [[Spiritual]] Warfare thus conceptualizes evangelism—quite graphically—as the re-appropriation of demonically colonized territory; as McAlister notes, "[[Satan]] becomes the colonial power who must be overthrown" (McAlister, 2012: 1). This counter-colonization [[effort]] was promulgated at several fronts over the next | ||

| − | Spiritual | + | decade. Lausanne's [[Spiritual]] Mappers met with the developer of an early PC-based Geographic [[Information]] Systems (GIS) {{Wiki|software}} and mapped a box between 10 and 40 degrees [[north]] latitude that became renowned in [[Spiritual]] Mapping circles as "the 10/40 Window." These were the central territories that needed to be |

| − | + | re-taken—regions in which the majority of its residents were "enslaved by {{Wiki|Islam}}, [[Hinduism]] and [[Buddhism]]" (cited in Judy Han, Ju [[Hui]], 2010: 186). Its {{Wiki|data}} was digitally integrated into a Mercator projection of the 10/40 Window, which was uploaded onto an enormous on-line network of [[prayer]] sites and | |

| − | + | [[information]] clearinghouses. [[Spiritual]] Mapping was graduating from a [[conversion]] strategy to a global {{Wiki|movement}}. | |

| + | By 1991, the technique of [[spiritual]] mapping was being prescribed for areas outside the 10/40 Window. In the [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]], these efforts were most commonly | ||

| − | + | directed at urban neighborhoods whose high rates of [[crime]], [[prostitution]], and {{Wiki|drug}} use were seen to bespeak the presence of unseen {{Wiki|demonic}} residents.26 [[Spiritual]] Mapping thus tacitly framed itself as a [[form]] of {{Wiki|community}} [[development]], though its leaders pointedly subsumed {{Wiki|social}} concerns to evangelical progress. | |

| − | |||

| − | It was two years later that the movement began to give greater attention to a different breed of domestic demon: those evidenced by the growth of non-Christian beliefs and practices in "the West." A 1993 Intersession Working Group identified the key changes in Western society that fed this trend: "An | + | It was two years later that the {{Wiki|movement}} began to give greater [[attention]] to a different breed of domestic {{Wiki|demon}}: those evidenced by the growth of non-Christian [[beliefs]] and practices in "the [[West]]." A 1993 Intersession Working Group identified the key changes in [[Western]] [[society]] that fed this trend: "An |

| − | Increased interest in Eastern Religion," the "Influx of Non-Christian Worldview" resulting from "the massive migrations of people from the Third World" and the "Sensationalization of the Occult" (Holvast, 2009: 231– 234.) It was in this final category that Tibetan Buddhism was specifically referenced. | + | Increased [[interest]] in {{Wiki|Eastern Religion}}," the "[[Influx]] of Non-Christian Worldview" resulting from "the massive migrations of [[people]] from the Third [[World]]" and the "Sensationalization of the [[Occult]]" (Holvast, 2009: 231– 234.) It was in this final category that [[Tibetan Buddhism]] was specifically referenced. |

| − | In 1996, The Dalai Lama travelled to Sydney, Australia to perform the "Kalachakra for World Peace." For the first time, the initiation was a source of active concern to a handful of local Spiritual Mappers. During that visit, | + | In 1996, [[The Dalai Lama]] travelled to {{Wiki|Sydney}}, [[Australia]] to perform the "[[Kalachakra]] for [[World Peace]]." For the first time, the [[initiation]] was a source of active [[concern]] to a handful of local [[Spiritual]] Mappers. During that visit, |

| − | the Dalai Lama was involved in a number of ceremonies that involved the completion of several sand based murals which upon completion were thrown into Sydney Harbour as a means of "blessing" the city. There was limited response only from a few experienced Intercessors. That response was basically limited | + | the [[Dalai Lama]] was involved in a number of {{Wiki|ceremonies}} that involved the completion of several sand based murals which upon completion were thrown into {{Wiki|Sydney}} Harbour as a means of "[[blessing]]" the city. There was limited response only from a few [[experienced]] Intercessors. That response was basically limited |

| − | to following the Dalai Lama as he journeyed around Sydney cleansing the places he visited through prayer, and where water was involved the casting of salt into the water to purify and cleanse the waters according to the Biblical principle in 2 Kings 2: 19–22. (B. Pickering, 12 March 2012, personal communication) | + | to following the [[Dalai Lama]] as he journeyed around {{Wiki|Sydney}} cleansing the places he visited through [[prayer]], and where [[water]] was involved the casting of [[salt]] into the [[water]] to {{Wiki|purify}} and cleanse the waters according to the {{Wiki|Biblical}} [[principle]] in 2 [[Kings]] 2: 19–22. (B. Pickering, 12 March 2012, personal [[communication]]) |

| − | 26 In the United States, the demand to "liberate" particular neighborhoods has spawned a cottage industry in guidebooks and video resources. See especially Cindy Jacobs' Possessing the Gates of the Enemy: A Training Manual for Militant Intersession (1991); John Dawson, Taking Our Cities for God: How to Break Spiritual Strongholds (1990); George Otis Jr., Informed Intersession: Transforming Your Community Through Spiritual Mapping and Strategic Prayer (1999) and his Transformations video series. | + | 26 In the [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]], the demand to "{{Wiki|liberate}}" particular neighborhoods has spawned a cottage industry in guidebooks and video resources. See especially Cindy Jacobs' Possessing the Gates of the Enemy: A Training Manual for Militant Intersession (1991); John Dawson, Taking Our Cities for [[God]]: How to Break [[Spiritual]] Strongholds (1990); George Otis Jr., Informed Intersession: [[Transforming]] Your {{Wiki|Community}} Through [[Spiritual]] Mapping and Strategic [[Prayer]] (1999) and his Transformations video series. |

| + | |||

| + | [[Spiritual]] Mapping [[anxiety]] about the [[Kālacakra]] blossomed three years later. In 1999, Victor and Victoria Trimondi (formerly Herbert and Victoria Röttgen) published a now infamous manifesto against [[Tibetan Buddhism]] and the [[Dalai Lama]] which placed especial {{Wiki|emphasis}} on the [[Kālacakra tradition]]. In the Trimondi's | ||

| − | + | highly rhetoricized and unscholarly presentation, "the [[Kalachakra Tantra]] and the [[Shambhala]] [[myth]] associated" are "the basis for the policy on [[religions]] of the [[Dalai Lama]]." Its goals included "the linking of [[religious]] and [[state]] power" and "the establishment of a global Buddhocracy via manipulative and warlike | |

| − | + | means." The "[[Kalachakra]] for [[World Peace]]" in {{Wiki|New York City}} served as exemplar of the [[initiation]], and had, they noted, explicitly anti-Christian undertones: "{{Wiki|Christ}} is named in the [[Kalachakra Tantra]] as one the '{{Wiki|heretics}}'" though the [[Dalai Lama]] "[[knows]] only too well that open to {{Wiki|integration}} of the {{Wiki|archetype}} of | |

| − | + | {{Wiki|Christ}} into his [[tantric]] [[pantheon]] would only lead to strong protests from the [[Christian]] (Trimondi, 2003). | |

| + | The Trimondis' piece (Victor Trimondi and Victoria Trimondi, 1999) began to circulate at roughly the same time as the 1999 "[[Kalachakra]] for [[World Peace]]" in | ||

| − | + | [[Bloomington]], [[Indiana]]. Subsequently, an English translation (Victor Trimondi and Victoria Trimondi, 2003) proliferated across the internet which would be repeatedly quoted (though less-often attributed) in [[Spiritual]] Mapping {{Wiki|literature}} over the next half decade. By the time our [[Spiritual]] [[Warriors]] [[gathered]] on the shores of Lake [[Ontario]] in 2004, the Trimondi's reading of the [[Kālacakra's]] putative {{Wiki|political}} agenda had been naturalized into Mapping conceptions. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ===[[Unpacking the Logic]]=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | The Spiritual Mapping equation of Tibetan Buddhism with "the Occult" underscores an important point: in Mapping thought, Tibetan Buddhism does not connote the rationality and ecumenicism of Buddhist Modernism, but its rhetorical opposite: "a belief in spirits and demons, secret sexual practices, [and] | + | The [[Spiritual]] Mapping equation of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] with "the [[Occult]]" underscores an important point: in Mapping [[thought]], [[Tibetan Buddhism]] does not connote the {{Wiki|rationality}} and ecumenicism of [[Buddhist Modernism]], but its [[Wikipedia:Rhetoric|rhetorical]] opposite: "a [[belief]] in [[spirits]] and {{Wiki|demons}}, secret {{Wiki|sexual}} practices, [and] |

| − | occultism" ruled by a "God-King" (Truthspeaker, 2011). Here, Tibetan Buddhism is placed in rhetorical opposition to the modern Spiritual Mapper armed with social science methods and cutting-edge GPS technology. The Spiritual Warriors are apparently taking back the upper hand of modernity by re-casting Tibetan Buddhism as the primitive "Lamaism" of their 19th century missionary predecessors. | + | [[occultism]]" ruled by a "[[God-King]]" (Truthspeaker, 2011). Here, [[Tibetan Buddhism]] is placed in [[Wikipedia:Rhetoric|rhetorical]] [[opposition]] to the {{Wiki|modern}} [[Spiritual]] Mapper armed with {{Wiki|social science}} [[methods]] and cutting-edge GPS technology. The [[Spiritual]] [[Warriors]] are apparently taking back the upper hand of modernity by re-casting [[Tibetan Buddhism]] as the primitive "[[Lamaism]]" of their 19th century {{Wiki|missionary}} predecessors. |

| − | Yet their relegation of Tibetan Buddhism to the occult underscores a more telling perception. Buddhism's danger lies less in its religious teachings than in its ritual technology: it is by means of the sand mandala by which Tibetan Buddhists are waging battle for American territorial domination.27 What is the thinking behind this conviction? Previously, I noted that Spiritual Mapping conceptualizes evangelism as the | + | Yet their relegation of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] to the [[occult]] underscores a more telling [[perception]]. [[Buddhism's]] [[danger]] lies less in its [[religious]] teachings than in its [[ritual]] technology: it is by means of the [[sand mandala]] by which [[Tibetan Buddhists]] are waging {{Wiki|battle}} for [[American]] territorial domination.27 What is the [[thinking]] behind this conviction? Previously, I noted that [[Spiritual]] Mapping conceptualizes evangelism as the |

| − | 27 It should be noted that this symbolic association of Tibetan nationalism, world peace and land inhabitation was buttressed by a number of other territory-centric world peace projects by Tibetan Buddhists in diaspora. The World Peace Vase Project, introduced in 1987, involved the consecration of | + | 27 It should be noted that this [[symbolic]] association of [[Tibetan]] [[nationalism]], [[world peace]] and land inhabitation was buttressed by a number of other territory-centric [[world peace]] projects by [[Tibetan Buddhists]] in {{Wiki|diaspora}}. The [[World Peace]] [[Vase]] Project, introduced in 1987, involved the [[consecration]] of |

| − | 6,200 "peace vases" to be buried across the globe. The World Peace Ceremonies, performed from 1989 onwards, included large scale prayers for World Peace at four principal pilgrimage sites associated with the Buddha's life. Since 1990, Stupas for World Peace constructed stupas at specific spots close to Tibetan monasteries in India and near various Tibetan religious establishments around the world. See Mills, 2009: 95–114. | + | 6,200 "[[peace]] vases" to be [[Wikipedia:burial|buried]] across the {{Wiki|globe}}. The [[World Peace]] {{Wiki|Ceremonies}}, performed from 1989 onwards, included large scale [[prayers]] for [[World Peace]] at four [[principal]] [[pilgrimage sites]] associated with the [[Buddha's life]]. Since 1990, [[Stupas]] for [[World Peace]] [[constructed]] [[stupas]] at specific spots close to [[Tibetan monasteries]] in [[India]] and near various [[Tibetan]] [[religious establishments]] around the [[world]]. See Mills, 2009: 95–114. |

| − | re-appropriation of demonically colonized territory. I used the term "colonization" deliberately; concerns about the legitimacy of territorial rule are central to Spiritual Warfare literature, which is infused with the language and logic of legality.28 The practice of Spiritual Warfare is constrained by | + | re-appropriation of demonically colonized territory. I used the term "colonization" deliberately; concerns about the legitimacy of territorial {{Wiki|rule}} are central to [[Spiritual]] Warfare {{Wiki|literature}}, which is [[infused]] with the [[language]] and [[logic]] of legality.28 The practice of [[Spiritual]] Warfare is constrained by |

| − | "the laws of protocol"—what one might call Biblically derived "rules of engagement." Demons are not squatters to be evicted. They have been "invited" through the sinful actions of its residents, and so are considered to have legal dominion over the lands they inhabit, granted to them by Satan himself.29 | + | "the laws of protocol"—what one might call Biblically derived "{{Wiki|rules}} of engagement." {{Wiki|Demons}} are not squatters to be evicted. They have been "invited" through the sinful [[actions]] of its residents, and so are considered to have legal dominion over the lands they inhabit, granted to them by [[Satan]] himself.29 |

It is only in accordance with these laws of protocol that they can be removed—and supplanted—by an authority with greater legal claim than they. | It is only in accordance with these laws of protocol that they can be removed—and supplanted—by an authority with greater legal claim than they. | ||

| − | In Spiritual Mapping understanding, the Dalai Lama is himself a high authority. The "God-King" of an "occult" tradition with geographical roots in the | + | In [[Spiritual]] Mapping [[understanding]], the [[Dalai Lama]] is himself a high authority. The "[[God-King]]" of an "[[occult]]" [[tradition]] with geographical [[roots]] in the |