Difference between revisions of "The Jhanas in Theravada Buddhist Meditation by Bhikkhu Henepola Gunaratana"

(Created page with "thumb|250px| <poem> The Jhanas in Theravada Buddhist Meditation by Bhikkhu Henepola Gunaratana Chapter 1 Introduction The Doct...") |

m (Text replacement - "]]]" to "]])") |

||

| (26 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{DisplayImages|21|3188|1758|1884|1992|1760|3363|891|3345|2402|1790|3110|2557|433|2370|2783|2581|2587|1302|664|3269|858|526|3036|1155|2797|933|766|3111|1904|619|1934|83|3242|570|34|397|1769|659|1373|486|3491|1433|2604|549|2873|2196|1566|2880|3090|1119|424|2894|3037|2577|2238}} | |

| − | < | + | {{Centre|<big><big>The Jhanas in Theravada Buddhist Meditation</big></big><br/> |

| − | The Jhanas in Theravada Buddhist Meditation | + | <big>by Bhikkhu Henepola Gunaratana</big><br/><br/> |

| − | by Bhikkhu Henepola Gunaratana | + | The Wheel Publication No. 351/353,<br/> |

| + | Buddhist Publication Society, Sri Lanka<br/> | ||

| + | Copyright 1988 by Henepola Gunaratana}}<br/><br/> | ||

| − | + | ==[[Chapter]] 1<br/>Introduction== | |

| − | + | ===The [[Doctrinal]] Context of [[Jhana]]=== | |

| − | + | The [[Buddha]] says that just as in the great ocean there is but one {{Wiki|taste}}, the {{Wiki|taste}} of [[salt]], so in his [[doctrine]] and [[discipline]] there is but one {{Wiki|taste}}, the {{Wiki|taste}} of freedom. The {{Wiki|taste}} of freedom that pervades the [[Buddha's teaching]] is the {{Wiki|taste}} of [[spiritual]] freedom, which from the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|perspective}} means freedom from [[suffering]]. | |

| − | + | In the process leading to [[deliverance]] from [[suffering]], [[meditation]] is the means of generating the inner [[awakening]] required for [[liberation]]. The methods of [[meditation]] [[taught]] in the [[Theravada]] [[Buddhist tradition]] are based on the [[Buddha's]] [[own]] [[experience]], forged by him in the course of his [[own]] quest for [[enlightenment]]. | |

| − | + | They are designed to re-create in the [[disciple]] who practices them the same [[essential]] [[enlightenment]] that the [[Buddha]] himself [[attained]] when he sat beneath the [[Bodhi tree]], the [[awakening]] to the [[Four Noble Truths]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The various [[subjects]] and methods of [[meditation]] expounded in the [[Theravada]] [[Buddhist scriptures]] -- the [[Pali Canon]] and its commentaries -- divide into two inter-related systems. One is called the [[development of serenity]] ([[samathabhavana]]), the other the [[development of insight]] ([[vipassanabhavana]]). The former also goes under the [[name]] of [[development of concentration]] ([[samadhibhavana]]), the [[latter]] the [[development of wisdom]] ([[pannabhavana]]). The practice of [[serenity]] [[meditation]] aims at developing a [[calm]], [[concentrated]], unified [[mind]] as a means of experiencing [[inner peace]] and as a basis for [[wisdom]]. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The practice of [[insight]] [[meditation]] aims at gaining a direct [[understanding]] of the real [[nature]] of [[phenomena]]. Of the two, the [[development of insight]] is regarded by [[Buddhism]] as the [[essential]] key to [[liberation]], the direct antidote to the [[ignorance]] underlying bondage and [[suffering]]. Whereas [[serenity]] [[meditation]] is [[recognized]] as common to both [[Buddhist]] and [[non-Buddhist]] {{Wiki|contemplative}} [[disciplines]], [[insight]] [[meditation]] is held to be the unique discovery of the [[Buddha]] and an unparalleled feature of his [[path]]. | |

| − | + | However, because the growth of [[insight]] presupposes a certain [[degree]] of [[concentration]], and [[serenity]] [[meditation]] helps to achieve this, the [[development of serenity]] also claims an incontestable place in the [[Buddhist]] [[meditative]] process. Together the two types of [[meditation]] work to make the [[mind]] a fit instrument for [[enlightenment]]. With his [[mind]] unified by means of the [[development of serenity]], made sharp and bright by the [[development of insight]], the [[meditator]] can proceed unobstructed to reach the end of [[suffering]], [[Nibbana]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Pivotal to both systems of [[meditation]], though belonging inherently to the side of [[serenity]], is a set of [[meditative]] [[attainments]] called the [[jhanas]]. Though [[translators]] have [[offered]] various renderings of this [[word]], ranging from the feeble "musing" to the misleading "[[trance]]" and the {{Wiki|ambiguous}} "[[meditation]]," we prefer to leave the [[word]] untranslated and to let its meaning emerge from its contextual usages. | |

| − | + | From these it is clear that the [[jhanas]] are states of deep [[mental]] unification which result from the centering of the [[mind]] upon a single [[object]] with such power of [[attention]] that a total immersion in the [[object]] takes place. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The early [[suttas]] speak of four [[jhanas]], named simply after their numerical position in the series: the [[first jhana]], the [[second jhana]], the [[third jhana]] and the [[forth jhana]]. In the [[suttas]] the four repeatedly appear each described by a standard [[formula]] which we will examine later in detail. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The importance of the [[jhanas]] in the [[Buddhist path]] can readily be gauged from the frequency with which they are mentioned throughout the [[suttas]]. The [[jhanas]] figure prominently both in the [[Buddha's]] [[own]] [[experience]] and in his exhortation to [[disciples]]. In his childhood, while attending an annual [[ploughing festival]], the [[future Buddha]] spontaneously entered the [[first jhana]]. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | It was the [[memory]] of this childhood incident, many years later after his futile pursuit of austerities, that revealed to him the way to [[enlightenment]] during his period of deepest [[despondency]] (M.i, 246-47). After taking his seat beneath the [[Bodhi tree]], the [[Buddha]] enter the four [[jhanas]] immediately before [[direction]] his [[mind]] to the [[threefold knowledge]] that issued in his [[enlightenment]] (M.i.247-49). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Throughout his active career the four [[jhanas]] remained "his [[heavenly]] dwelling" (D.iii,220) to which he resorted in order to live happily here and now. His [[understanding]] of the corruption, [[purification]] and [[emergence]] in the [[jhanas]] and other [[meditative]] [[attainments]] is one of the [[Tathagata's]] [[ten powers]] which enable him to turn the matchless [[wheel]] of the [[Dhamma]] (M.i,70). Just before his passing away the [[Buddha]] entered the [[jhanas]] in direct and reverse order, and the passing away itself took place directly from the [[fourth jhana]] (D.ii,156). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Buddha]] is constantly seen in the [[suttas]] encouraging his [[disciples]] to develop [[jhana]]. The four [[jhanas]] are invariably included in the complete course of {{Wiki|training}} laid down for [[disciples]].<ref>See for example, the [[Samannaphala Sutta]] (D. 2), the [[Culahatthipadopama Sutta]] (M. 27),etc.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | They figure in the {{Wiki|training}} as the [[discipline]] of [[higher consciousness]] ([[adhicittasikkha]]), [[right concentration]] ([[sammasamadhi]]) of the [[Noble Eightfold Path]], and the {{Wiki|faculty}} and power of [[concentration]] ([[samadhindriya]], [[samadhibala]]). Though a [[vehicle]] of dry [[insight]] can be found, indications are that this [[path]] is not an easy one, lacking the aid of the powerful [[serenity]] available to the [[practitioner]] of [[jhana]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The way of the [[jhana]] attainer seems by comparison smoother and more [[pleasurable]] (A.ii,150-52). The [[Buddha]] even refers to the four [[jhanas]] figuratively as a kind of [[Nibbana]]: he calls them immediately [[visible]] [[Nibbana]], factorial [[Nibbana]], [[Nibbana]] here and now (A.iv,453-54). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | To attain the [[jhanas]], the [[meditator]] must begin by eliminating the [[unwholesome]] [[mental states]] obstructing inner collectedness, generally grouped together as the [[five hindrances]] ([[pancanivarana]]): [[sensual desire]], [[ill will]], [[sloth and torpor]], [[restlessness]] and {{Wiki|worry}} and [[doubt]].<ref>[[Kamacchanda]], [[byapada]], [[thinamiddha]], [[uddhaccakukkucca]], [[vicikiccha]]. </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[mind's]] [[absorption]] on its [[object]] is brought about by five opposing [[mental states ]]-- applied [[thought]], sustained [[thought]], [[rapture]], [[happiness]] and [[one pointedness]]<ref>[[Vitakka]], [[vicara]], [[piti]], [[sukha]], [[ekaggata]]. </ref> -- called the [[jhana]] factors ([[jhanangani]]) because they lift the [[mind]] to the level of the [[first jhana]] and remain there as its defining components. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | After reaching the [[first jhana]] the ardent [[meditator]] can go on to reach the higher [[jhanas]], which is done by eliminating the coarser factors in each [[jhana]]. Beyond the four [[jhanas]] lies another fourfold set of higher [[meditative]] states which deepen still further the [[element]] of [[serenity]]. These [[attainments]] ([[aruppa]]), are the base of [[boundless space]], the base of [[boundless consciousness]], the base of [[nothingness]], and the base of [[neither-perception-nor-non-perception]].<ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Akasanancayatana]], [[vinnanancayatana]], [[akincannayatana]], [[nevasannanasannayatana]]. </ref> In the [[Pali commentaries]] these come to be called the four {{Wiki|immaterial}} [[jhanas]] ([[arupajhana]]), the four preceding states being renamed for the [[sake]] of clarity, the four fine-material [[jhanas]] ([[rupajhana]]). Often the two sets are joined together under the collective title of the eight [[jhanas]] or the [[eight attainments]] ([[atthasamapattiyo]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The four [[jhanas]] and the four {{Wiki|immaterial}} [[attainments]] appear initially as [[mundane]] states of deep [[serenity]] pertaining to the preliminary stage of the [[Buddhist path]], and on this level they help provide the base of [[concentration]] needed for [[wisdom]] to arise. But the four [[jhanas]] again reappear in a later stage in the [[development]] of the [[path]], in direct association with liberating [[wisdom]], and they are then designated the [[supramundane]] ([[lokuttara]]) [[jhanas]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These [[supramundane jhanas]] are the levels of [[concentration]] pertaining to the four degrees of [[enlightenment]] [[experience]] called the [[supramundane paths]] ([[magga]]) and the [[stages of liberation]] resulting [[form]] them, the four {{Wiki|fruits}} ([[phala]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Finally, even after full [[liberation]] is achieved, the [[mundane]] [[jhanas]] can still remain as [[attainments]] available to the fully {{Wiki|liberated}} [[person]], part of his untrammeled {{Wiki|contemplative}} [[experience]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==={{Wiki|Etymology}} of [[Jhana]]=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The great [[Buddhist]] commentator [[Buddhaghosa]] traces the [[Pali]] [[word]] "[[jhana]]" (Skt. [[dhyana]]) to two [[verbal]] [[forms]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One, the {{Wiki|etymologically}} correct derivation, is the verb [[jhayati]], meaning to think or [[meditate]]; the other is a more playful derivation, intended to [[illuminate]] its [[function]] rather than its [[verbal]] source, from the verb [[jhapeti]] meaning to burn up. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He explains: "It burns up opposing states, thus it is [[jhana]]" (Vin.A. i, 116), the purport being that [[jhana]] "burns up" or destroys the [[mental defilements]] preventing the developing the [[development of serenity]] and [[insight]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In the same passage [[Buddhaghosa]] says that [[jhana]] has the [[characteristic]] mark of contemplation ([[upanijjhana]]). Contemplation, he states, is twofold: the contemplation of the [[object]] and the contemplation of the [[characteristics]] of [[phenomena]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The former is exercised by the [[eight attainments]] of [[serenity]] together with their access, since these [[contemplate]] the [[object]] used as the basis for developing [[concentration]]; for this [[reason]] these [[attainments]] are given the [[name]] "[[jhana]]" in the {{Wiki|mainstream}} of [[Pali]] [[meditative]] [[exposition]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, [[Buddhaghosa]] also allows that the term "[[jhana]]" can be extended loosely to [[insight]] ([[vipassana]]), the [[paths]] and the {{Wiki|fruits}} on the ground that these perform the work of contemplating the [[characteristics]] of things the three marks of [[impermanence]], [[suffering]] and [[non-self]] in the case of [[insight]], [[Nibbana]] in the case of the [[paths]] and {{Wiki|fruits}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In brief the twofold meaning of [[jhana]] as "contemplation" and "burning up" can be brought into connection with the [[meditative]] process as follows. By fixing his [[mind]] on the [[object]] the [[meditator]] reduces and eliminates the lower [[mental]] qualities such as the [[five hindrances]] and promotes the growth of the higher qualities such as the [[jhana]] factors, which lead the [[mind]] to complete [[absorption]] in the [[object]]. Then by contemplating the [[characteristics]] of [[phenomena]] with [[insight]], the [[meditator]] eventually reaches the [[supramundane]] [[jhana]] of the four [[paths]], and with this [[jhana]] he burns up the [[defilements]] and attains the liberating [[experience]] of the {{Wiki|fruits}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===[[Jhana]] and [[Samadhi]]=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In the vocabulary of [[Buddhist meditation]] the [[word]] "[[jhana]]" is closely connected with another [[word]], "[[samadhi]]" generally rendered by "[[concentration]]." [[Samadhi]] derives from the prefixed [[verbal]] [[root]] [[sam-a-dha]], meaning to collect or to bring together, thus suggesting the [[concentration]] or unification of the [[mind]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[word]] "[[samadhi]]" is almost interchangeable with the [[word]] "[[samatha]]," [[serenity]], though the [[latter]] comes from a different [[root]], sam, meaning to become [[calm]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In the [[suttas]] [[samadhi]] is defined as [[mental]] [[one-pointedness]], (cittass'ekaggata M.i,301) and this [[definition]] is followed through rigorously in the [[Abhidhamma]]. The [[Abhidhamma]] treats [[one-pointedness]] as a {{Wiki|distinct}} [[mental factor]] {{Wiki|present}} in every [[state of consciousness]], exercising the [[function]] of unifying the [[mind]] on its [[object]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | From this strict [[psychological]] standpoint [[samadhi]] can be {{Wiki|present}} in [[unwholesome]] states of [[consciousness]] as well as in [[wholesome]] an [[neutral]] states. In its [[unwholesome]] [[forms]] it is called "[[wrong concentration]]" ([[micchasamadhi]]), In its [[wholesome]] [[forms]] "[[right concentration]]" ([[sammasamadhi]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In [[expositions]] on the practice of [[meditation]], however, [[samadhi]] is limited to [[one-pointedness of mind]] (Vism.84-85; PP.84-85), and even here we can understand from the context that the [[word]] means only the [[wholesome]] [[one-pointedness]] involved in the deliberate transmutation of the [[mind]] to a heightened level of [[calm]]. Thus [[Buddhaghosa]] explains [[samadhi]] {{Wiki|etymologically}} as "the centering of [[consciousness]] and [[consciousness]] [[concomitants]] evenly and rightly on a single [[object]] ... the [[state]] in [[virtue]] of which [[consciousness]] and its [[concomitants]] remain evenly and rightly on a single [[object]], undistracted and unscattered" (Vism.84-85; PP.85). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | However, despite the commentator's bid for [[consistency]], the [[word]] [[samadhi]] is used in the [[Pali literature]] on [[meditation]] with varying degrees of specificity of meaning. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the narrowest [[sense]], as defined by [[Buddhaghosa]], it denotes the particular [[mental factor]] responsible for the {{Wiki|concentrating}} of the [[mind]], namely, [[one-pointedness]]. In a wider [[sense]] it can signify the states of unified [[consciousness]] that result from the strengthening of [[concentration]], i.e. the [[meditative]] [[attainments]] of [[serenity]] and the stages leading up to them. | ||

| + | |||

| + | And in a still wider [[sense]] the [[word]] [[samadhi]] can be applied to the method of practice used to produce and cultivate these refined states of [[concentration]], here being {{Wiki|equivalent}} to the [[development of serenity]]. It is in the second [[sense]] that [[samadhi]] and [[jhana]] come closest in meaning. The [[Buddha]] explains [[right concentration]] as the four [[jhanas]] (D.ii,313), and in doing so allows [[concentration]] to encompass the [[meditative]] [[attainments]] signified by the [[jhanas]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, even though [[jhana]] and [[samadhi]] can overlap in denotation, certain differences in their suggested and contextual meanings prevent unqualified identification of the two terms. First behind the [[Buddha's]] use of the [[jhana]] [[formula]] to explain [[right concentration]] lies a more technical [[understanding]] of the terms. | ||

| + | |||

| + | According to this [[understanding]] [[samadhi]] can be narrowed down in range to signify only one [[mental factor]], the most prominent in the [[jhana]], namely, [[one-pointedness]], while the [[word]] "[[jhana]]" itself must be seen as encompassing the [[state of consciousness]] in its entirety, or at least the whole group of [[mental factors]] individuating that [[meditative]] [[state]] as a [[jhana]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | In the second place, when [[samadhi]] is considered in its broader meaning it involves a wider range of reference than [[jhana]]. The [[Pali]] {{Wiki|exegetical}} [[tradition]] [[recognizes]] three levels of [[samadhi]]: [[preliminary concentration]] ([[parikammasamadhi]]), which is produced as a result of the [[meditator's]] initial efforts to focus his [[mind]] on his [[meditation]] [[subject]]; [[access concentration]] ([[upacarasamadhi]]), marked by the suppression of the [[five hindrances]], | ||

| + | |||

| + | the [[manifestation of the jhana]] factors, and the [[appearance]] of a {{Wiki|luminous}} [[mental]] replica of the [[meditation]] [[object]] called the [[counterpart sign]] ([[patibhaganimitta]]); and [[absorption]] [[concentration]] ([[appanasamadhi]]), the complete immersion of the [[mind]] in its [[object]] effected by the full {{Wiki|maturation}} of the [[jhana]] factors.<ref>See [[Narada]], A [[Manual of Abhidhamma]]. 4th ed. ({{Wiki|Kandy}}: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Buddhist Publication Society]], 1980), pp.389, 395-96 </ref> [[Absorption]] [[concentration]] comprises the [[eight attainments]], the four {{Wiki|immaterial}} [[attainments]], and to this extent [[jhana]] and [[samadhi]] coincide. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, [[samadhi]] still has a broader scope than [[jhana]], since it includes not only the [[jhanas]] themselves but also the two preparatory degrees of [[concentration]] leading up to them. Further, [[samadhi]] also covers a still different type of [[concentration]] called [[momentary concentration]] ([[khanikasamadhi]]), the mobile [[mental]] stabilization produced in the course of [[insight]] contemplation of the passing flow of [[phenomena]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==[[Chapter]] 2<br/>The Preparation for [[Jhana]]== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The [[jhanas]] do not arise out of a [[void]] but in [[dependence]] on the right [[conditions]]. They come to growth only when provided with the [[nutriments]] conductive to their [[development]]. Therefore, prior to beginning [[meditation]], the aspirant to the [[jhanas]] must prepare a groundwork for his practice by fulfilling certain preliminary requirements. | ||

| + | |||

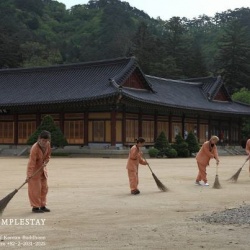

| + | He first must endeavor to {{Wiki|purify}} his [[moral]] [[virtue]], sever the outer impediments to practice, and place himself under a qualified [[teacher]] who will assign him a suitable [[meditation]] [[subject]] and explain to him the methods of developing it. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After {{Wiki|learning}} these the [[disciple]] must then seek out a congenial dwelling and diligently strive for [[success]]. In this [[chapter]] we will examine in order each of the preparatory steps that have to be fulfilled before commencing to develop [[jhana]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===The [[Moral]] Foundation for [[Jhana]]=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | A [[disciple]] aspiring to the [[jhanas]] first has to lay a solid foundation of [[moral discipline]]. [[Moral]] [[purity]] is indispensable to [[meditative]] progress for several deeply [[psychological]] [[reasons]]. It is needed first, in order to safeguard against the [[danger]] of {{Wiki|remorse}}, the nagging [[sense]] of [[guilt]] that arises when the basic {{Wiki|principles}} of [[morality]] are ignored or deliberately violated. Scrupulous conformity to [[virtuous]] {{Wiki|rules}} of conduct protects the [[mediator]] from this [[danger]] disruptive to inner [[calm]], and brings [[joy]] and [[happiness]] when the [[mediator]] reflects upon the [[purity]] of his conduct (see A.v,1-7). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | A second [[reason]] a [[moral]] foundation is needed for [[meditation]] follows from an [[understanding]] of the {{Wiki|purpose}} of [[concentration]]. [[Concentration]], in the [[Buddhist]] [[discipline]], aims at providing a base for [[wisdom]] by cleansing the [[mind]] of the dispersive influence of the [[defilements]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | But in order for the [[concentration]] exercises to effectively combat the [[defilements]], the coarser {{Wiki|expressions}} of the [[latter]] through [[bodily]] and [[verbal]] [[action]] first have to be checked. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Moral]] transgressions being invariably motivated by [[defilements]] -- by [[greed]], [[hatred]] and [[delusion]] -- when a [[person]] acts in {{Wiki|violation}} of the [[precepts]] of [[morality]] he excites and reinforces the very same [[mental factors]] his practice of [[meditation]] is intended to eliminate. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This involves him in a crossfire of incompatible aims which renders his attempts at [[mental]] [[purification]] ineffective. The only way he can avoid [[frustration]] in his endeavor to {{Wiki|purify}} the [[mind]] of its subtler [[defilements]] is to prevent the [[unwholesome]] inner {{Wiki|impulses}} from [[breathing]] out in the coarser [[form]] of [[unwholesome]] [[bodily]] and [[verbal]] [[deeds]]. Only when he establishes control over the outer expression of the [[defilements]] can he turn to deal with them inwardly as [[mental]] {{Wiki|obsessions}} that appear in the process of [[meditation]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The practice of [[moral discipline]] consists negatively in [[abstinence]] from [[immoral]] [[actions]] of [[body]] and {{Wiki|speech}} and positively in the [[observance]] of [[ethical]] {{Wiki|principles}} promoting [[peace]] within oneself and [[harmony]] in one's relations with others. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The basic code of [[moral discipline]] [[taught]] by the [[Buddha]] for the guidance of his lay followers is the [[five precepts]]: [[abstinence]] from taking [[life]], from [[stealing]], from {{Wiki|sexual}} {{Wiki|misconduct}}, from false {{Wiki|speech}}, and from [[intoxicating]] [[drugs]] and drinks. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These {{Wiki|principles}} are bindings as minimal [[ethical]] obligations for all practitioners of the [[Buddhist path]], and within their bounds considerable progress in [[meditation]] can be made. However, those aspiring to reach the higher levels of [[jhanas]] and to pursue the [[path]] further to the stages of [[liberation]], are encouraged to take up the more complete [[moral discipline]] pertaining to the [[life]] of [[renunciation]]. [[Early Buddhism]] is unambiguous in its {{Wiki|emphasis}} on the limitations of [[household life]] for following the [[path]] in its fullness and [[perfection]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Time]] and again the texts say that the [[household life]] is confining, a "[[path]] for the dust of [[passion]]," while the [[life]] of homelessness is like open [[space]]. Thus a [[disciple]] who is fully intent upon making rapid progress towards [[Nibbana]] will when outer [[conditions]] allow for it, "shave off his [[hair]] and beard, put on the [[yellow robe]], and go forth from the [[home]] [[life]] into homelessness" (M.i,179). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The [[moral]] {{Wiki|training}} for the [[bhikkhus]] or [[monks]] has been arranged into a system called the fourfold [[purification of morality]] ([[catuparisuddhisila]]).<ref>A full description of the fourfold [[purification of morality]] will be found in the [[Visuddhimagga]], [[Chapter]] 1. </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first component of this scheme, its {{Wiki|backbone}}, consists in the [[morality]] of {{Wiki|restraint}} according to the [[Patimokkha]], the code of 227 {{Wiki|training}} [[precepts]] promulgated by the [[Buddha]] to regulate the conduct of the [[Sangha]] or [[monastic order]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Each of these {{Wiki|rules}} is in some way intended to facilitate control over the [[defilements]] and to induce a mode of living marked by [[harmlessness]], [[contentment]] and [[simplicity]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The second aspect of the [[monk's]] [[moral discipline]] is {{Wiki|restraint}} of the [[senses]], by which the [[monk]] maintains close watchfulness over his [[mind]] as he engages in [[sense]] contacts so that he does not give rise to [[desire]] for [[pleasurable]] [[objects]] and [[aversion]] towards repulsive ones. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Third, the [[monk]] is to live by a [[purified]] [[livelihood]], obtaining his basic requisites such as [[robes]] [[food]], lodgings and {{Wiki|medicines}} in ways consistent with his vocation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The fourth factor of the [[moral]] {{Wiki|training}} is proper use of the requisites, which means that the [[monk]] should reflect upon the purposes for which he makes use of his requisites and should employ them only for maintaining his [[health]] and {{Wiki|comfort}}, not for {{Wiki|luxury}} and [[enjoyment]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | After establishing a foundation of [[purified]] [[morality]], the aspirant to [[meditation]] is advised to cut off any outer impediments (palibodha) that may hinder his efforts to lead a {{Wiki|contemplative}} [[life]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These impediments are numbered as ten: a dwelling, which becomes an impediment for those who allow their [[minds]] to become preoccupied with its upkeep or with its appurtenances; | ||

| + | |||

| + | a [[family]] of relatives or supporters with whom the aspirant may become [[emotionally]] involved in ways that hinder his progress; gains, which may bind the [[monk]] by {{Wiki|obligation}} to those who offer them; a class of students who must be instructed; building work, which demands [[time]] and [[attention]]; | ||

| + | |||

| + | travel; kin, meaning [[parents]], [[teachers]], pupils or close friends; {{Wiki|illness}}; the study of [[scriptures]]; and [[supernormal powers]], which are an impediment to [[insight]] (Vism.90-97; PP.91-98). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===The [[Good Friend]] and the [[Subject]] of [[Meditation]]=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

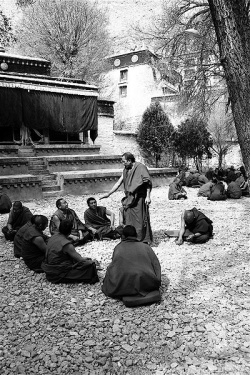

| + | The [[path]] of practice leading to the [[jhanas]] is an arduous course involving precise techniques and skillfulness is needed in dealing with the pitfalls that lie along the way. The [[knowledge]] of how to attain the [[jhanas]] has been transmitted through a [[lineage]] of [[teachers]] going back to the [[time]] of the [[Buddha]] himself. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A prospective [[meditator]] is advised to avail himself of the living heritage of [[accumulated]] [[knowledge]] and [[experience]] by placing himself under the care of a qualified [[teacher]], described as a "[[good friend]]" ([[kalyanamitta]]), one who gives guidance and [[wise]] advice rooted in his [[own]] practice and [[experience]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the basis of either of the power of penetrating others [[minds]], or by personal observation, or by questioning, the [[teacher]] will size up the {{Wiki|temperament}} of his new pupil and then select a [[mediation]] [[subject]] for him appropriate to his {{Wiki|temperament}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The various [[meditation]] [[subjects]] that the [[Buddha]] prescribed for the [[development of serenity]] have been collected in the commentaries into a set called the forty [[kammatthana]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This [[word]] means literally a place of work, and is applied to the [[subject]] of [[meditation]] as the place where the [[meditator]] undertakes the work of [[meditation]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The forty [[meditation]] [[subjects]] are distributed into seven categories, enumerated in the [[Visuddhimagga]] as follows: ten [[kasinas]], ten kinds of [[foulness]], ten [[recollections]], four [[divine]] abidings, four {{Wiki|immaterial}} states, one [[perception]], and one defining.<ref>The following [[discussion]] is based on Vism.110-115; PP.112-118.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | A [[kasina]] is a device representing a particular [[quality]] used as a support for [[concentration]]. The ten [[kasinas]] are those of [[earth]], [[water]], [[fire]] and [[air]]; four {{Wiki|color}} [[kasinas]] -- blue, [[yellow]], [[red]] and white; the {{Wiki|light}} [[kasina]] and the limited [[space]] [[kasina]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[kasina]] can be either a naturally occurring [[form]] of the [[element]] or {{Wiki|color}} chosen, or an {{Wiki|artificially}} produced device such as a disk that the [[meditator]] can use at his convenience in his [[meditation]] quarters. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The ten kinds of [[foulness]] are [[ten stages]] in the decomposition of a corpse: the bloated, the livid, the festering, the cut-up, the gnawed, the scattered, the hacked and scattered, the bleeding, the worm-infested and a skeleton. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The primary {{Wiki|purpose}} of these [[meditations]] is to reduce {{Wiki|sensual}} [[lust]] by gaining a clear [[perception]] of the repulsiveness of the [[body]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The ten [[recollections]] are the [[recollections]] of the [[Buddha]], the [[Dhamma]], the [[Sangha]], [[morality]], [[generosity]] and the [[deities]], [[mindfulness]] of [[death]], [[mindfulness]] of the [[body]], [[mindfulness of breathing]], and the [[recollection]] of [[peace]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first three are devotional contemplations on the [[sublime]] qualities of the "[[Three Jewels]]," the primary [[objects]] of [[Buddhist]] [[virtues]] and on the [[deities]] inhabiting the [[heavenly]] [[worlds]], intended principally for those still intent on a higher [[rebirth]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Mindfulness]] of [[death]] is {{Wiki|reflection}} on the inevitably of [[death]], a [[constant]] spur to [[spiritual]] {{Wiki|exertion}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Mindfulness]] of the [[body]] involves the [[mental]] dissection of the [[body]] into thirty-two parts, undertaken with a [[view]] to perceiving its unattractiveness. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Mindfulness of breathing]] is [[awareness]] of the in-and-out {{Wiki|movement}} of the [[breath]], perhaps the most fundamental of all [[Buddhist meditation]] [[subjects]]. And the [[recollection]] of [[peace]] is {{Wiki|reflection}} on the qualities of [[Nibbana]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

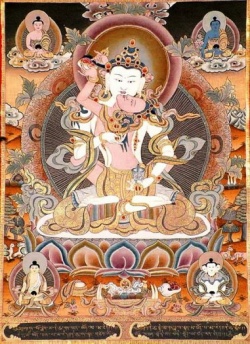

| + | The four [[divine]] abidings ([[brahmavihara]]) are the [[development]] of [[boundless]] [[loving-kindness]], [[compassion]], [[sympathetic joy]] and [[equanimity]]. These [[meditations]] are also called the "[[immeasurables]]" ([[appamanna]]) because they are to be developed towards all [[sentient beings]] without qualification or exclusiveness. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The four {{Wiki|immaterial}} states are the base of [[boundless space]], the base of [[boundless consciousness]], the base of [[nothingness]], and the base of [[neither-perception-nor-non-perception]]. These are the [[objects]] leading to the corresponding [[meditative]] [[attainments]], the {{Wiki|immaterial}} [[jhanas]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The one [[perception]] is the [[perception]] of the repulsiveness of [[food]]. The one defining is the defining of the [[four elements]], that is, the analysis of the [[physical body]] into the [[elemental]] modes of {{Wiki|solidity}}, {{Wiki|fluidity}}, heat and oscillation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The forty [[meditation]] [[subjects]] are treated in the {{Wiki|commentarial}} texts from two important angles -- one their ability to induce different levels of [[concentration]], the other their suitability for differing temperaments. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Not all [[meditation]] [[subjects]] are equally effective in inducing the deeper levels of [[concentration]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | They are first {{Wiki|distinguished}} on the basis of their capacity for inducing only [[access concentration]] or for inducing full [[absorption]]; those capable of inducing [[absorption]] are then {{Wiki|distinguished}} further according to their ability to induce the different levels of [[jhana]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Of the forty [[subjects]], ten are capable of leading only to [[access concentration]]: eight [[recollections]] -- i.e. all except [[mindfulness]] of the [[body]] and [[mindfulness of breathing]] -- plus the [[perception]] of repulsiveness in nutriment and the defining of the [[four elements]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | These, because they are occupied with a diversity of qualities and involve and active application of discursive [[thought]], cannot lead beyond access. The other thirty [[subjects]] can all lead to [[absorption]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The ten [[kasinas]] and [[mindfulness of breathing]], owing to their [[simplicity]] and freedom from [[thought]] construction, can lead to all four [[jhanas]]. The ten kinds of [[foulness]] and [[mindfulness]] of the [[body]] lead only to the [[first jhana]], being limited because the [[mind]] can only hold onto them with the aid of applied [[thought]] ([[vitakka]]) which is absent in the second and higher [[jhanas]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first three [[divine]] abidings can induce the lower three [[jhanas]] but the fourth, since they arise in association with [[pleasant]] [[feeling]], while the [[divine]] abiding of [[equanimity]] occurs only at the level of the [[fourth jhana]], where [[neutral]] [[feeling]] gains ascendency. The four {{Wiki|immaterial}} states conduce to the respective {{Wiki|immaterial}} [[jhanas]] corresponding to their names. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The forty [[subjects]] are also differentiated according to their appropriateness for different [[character]] types. Six main [[character]] types are [[recognized]] -- the [[greedy]], the hating, the deluded, the faithful, the {{Wiki|intelligent}} and the speculative -- this oversimplified [[typology]] being taken only as a {{Wiki|pragmatic}} guideline which in practice admits various shades and combinations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The ten kind of [[foulness]] and [[mindfulness]] of the [[body]], clearly intended to attenuate [[sensual desire]], are suitable for those of [[greedy]] {{Wiki|temperament}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Eight [[subjects]] -- the four [[divine]] abidings and four {{Wiki|color}} [[kasinas]] -- are appropriate for the hating {{Wiki|temperament}}. [[Mindfulness of breathing]] is suitable for those of the deluded and the speculative {{Wiki|temperament}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first [[six recollections]] are appropriate for the faithful {{Wiki|temperament}}. [[Four subjects]] -- [[mindfulness]] of [[death]], the [[recollection]] of [[peace]], the defining of the [[four elements]], and the [[perception]] of the repulsiveness in nutriment -- are especially effective for those of {{Wiki|intelligent}} {{Wiki|temperament}}. The remaining six [[kasinas]] and the {{Wiki|immaterial}} states are suitable for all kinds of temperaments. But the [[kasinas]] should be limited in size for one of speculative {{Wiki|temperament}} and large in size for one of deluded {{Wiki|temperament}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Immediately after giving this breakdown [[Buddhaghosa]] adds a proviso to prevent {{Wiki|misunderstanding}}. He states that this [[division]] by way of {{Wiki|temperament}} is made on the basis of direct [[opposition]] and complete suitability, but actually there is no [[wholesome]] [[form]] of [[meditation]] that does not suppress the [[defilements]] and strengthen the [[virtuous]] [[mental factors]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Thus an {{Wiki|individual}} [[mediator]] may be advised to [[meditate]] on [[foulness]] to abandon [[lust]], on [[loving-kindness]] to abandon [[hatred]], on [[breathing]] to cut off discursive [[thought]], and on [[impermanence]] to eliminate the [[conceit]] "I am" (A.iv,358). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===Choosing a Suitable Dwelling=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The [[teacher]] assigns a [[meditation]] [[subject]] to his pupil appropriate to his [[character]] and explains the methods of developing it. He can teach it gradually to a pupil who is going to remain in close proximity to him, or in detail to one who will go to practice it elsewhere. If the [[disciple]] is not going to stay with his [[teacher]] he must be careful to select a suitable place for [[meditation]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The texts mention eighteen kinds of [[monasteries]] unfavorable to the [[development]] of [[jhana]]: a large [[monastery]], a new one, a dilapidated one, one near a road, one with a pond, leaves, [[flowers]] or {{Wiki|fruits}}, one sought after by many [[people]], | ||

| + | |||

| + | one in cities, among timber of fields, where [[people]] quarrel, in a port, in border lands, on a frontier, a haunted place, and one without access to a [[spiritual teacher]] (Vism. 118-121; PP122-125). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The factors which make a dwelling favorable to [[meditation]] are mentioned by the [[Buddha]] himself. If should not be too far from or too near a village that can be relied on as an [[alms]] resort, and should have a clear [[path]]: it should be quiet and secluded; it should be free from rough weather and from harmful {{Wiki|insects}} and [[animals]]; one should be [[able]] to obtain one's [[physical]] requisites while dwelling there; and the dwelling should provide ready access to learned [[elders]] and [[spiritual]] friends who can be consulted when problems arise in [[meditation]] (A.v,15). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The types of dwelling places commended by the [[Buddha]] most frequently in the [[suttas]] as conductive to the [[jhanas]] are a secluded dwelling in the {{Wiki|forest}}, at the foot of a [[tree]], on a mountain, in a cleft, in a {{Wiki|cave}}, in a [[cemetery]], on a wooded flatland, in the open [[air]], or on a heap of straw (M.i,181). Having found a suitable dwelling and settled there, the [[disciple]] should maintain scrupulous [[observance]] of the {{Wiki|rules}} of [[discipline]], He should be content with his simple requisites, exercise control over his [[sense faculties]], be [[mindful]] and discerning in all [[activities]], and practice [[meditation]] diligently as he was instructed. It is at this point that he meets the first great challenge of his {{Wiki|contemplative}} [[life]], the {{Wiki|battle}} with the [[five hindrances]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==[[Chapter]] 3<br/>The [[First Jhana]] and Its Factors== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The [[attainment]] of any [[jhana]] comes about through a twofold process of [[development]]. On one side the states obstructive to it, called its factors of [[abandonment]], have to be eliminated, on the other the states composing it, called its factors of possession, have to be acquired. In the case of the [[first jhana]] the factors of [[abandonment]] are the [[five hindrances]] and the factors of possession the five basic [[jhana]] factors. Both are alluded to in the standard [[formula]] for the [[first jhana]], the opening [[phrase]] referring to the [[abandonment]] of the [[hindrances]] and the subsequent portion enumerating the [[jhana]] factors: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Quite secluded from [[sense]] [[pleasures]], secluded from [[unwholesome]] [[states of mind]], he enters and dwells in the [[first jhana]], which is accompanied by applied [[thought]] and sustained [[thought]] with [[rapture]] and [[happiness]] born of [[seclusion]]. (M.i,1818; Vbh.245) | ||

| + | |||

| + | In this [[chapter]] we will first discuss the [[five hindrances]] and their [[abandonment]], then we will investigate the [[jhana]] factors both individually and by way of their combined contribution to the [[attainment]] of the [[first jhana]]. We will close the [[chapter]] with some remarks on the ways of perfecting the [[first jhana]], a necessary preparation for the further [[development of concentration]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The [[Abandoning]] of the [[Hindrances]]=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[five hindrances]] ([[pancanivarana]]) are [[sensual desire]], [[ill will]], [[sloth and torpor]], [[restlessness]] and {{Wiki|worry}}, and [[doubt]]. This group, the [[principal]] {{Wiki|classification}} the [[Buddha]] uses for the [[obstacles]] to [[meditation]], receives its [[name]] because its five members hinder and envelop the [[mind]], preventing [[meditative]] [[development]] in the two [[spheres]] of [[serenity]] and [[insight]]. Hence the [[Buddha]] calls them "obstructions, [[hindrances]], [[corruptions]] of the [[mind]] which weaken wisdom"(S.v,94). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[hindrance]] of [[sensual desire]] ([[kamachanda]]) is explained as [[desire]] for the "five [[strands]] of [[sense]] [[pleasure]]," that is, for [[pleasant]] [[forms]], {{Wiki|sounds}}, {{Wiki|smells}}, {{Wiki|tastes}} and tangibles. It ranges from {{Wiki|subtle}} liking to powerful [[lust]]. The [[hindrance]] of [[ill will]] ([[byapada]]) {{Wiki|signifies}} [[aversion]] directed towards [[disagreeable]] persons or things. It can vary in range from mild [[annoyance]] to overpowering [[hatred]]. Thus the first [[two hindrances]] correspond to the first two [[root]] [[defilements]], [[greed]] and [[hate]]. The third [[root]] [[defilement]], [[delusion]], is not enumerated separately among the [[hindrances]] but can be found underlying the remaining three. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Sloth and torpor]] is a compound [[hindrance]] made up of two components: [[sloth]] ([[thina]]), which is [[dullness]], {{Wiki|inertia}} or [[mental]] stiffness; and {{Wiki|torpor}} ([[middha]]), which is indolence or [[drowsiness]]. [[Restlessness]] and {{Wiki|worry}} is another double [[hindrance]], [[restlessness]] ([[uddhacca]]) being explained as [[excitement]], [[agitation]] or disquietude, {{Wiki|worry}} ([[kukkucca]]) as the [[sense]] of [[guilt]] aroused by [[moral]] transgressions. Finally, the [[hindrance]] of [[doubt]] ([[vicikiccha]]) is explained as uncertainty with regard to the [[Buddha]], the [[Dhamma]], the [[Sangha]] and the {{Wiki|training}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Buddha]] offers two sets of similes to illustrate the detrimental effect of the [[hindrances]]. The first compares the [[five hindrances]] to five types of calamity: [[sensual desire]] is like a debt, [[ill will]] like a {{Wiki|disease}}, [[sloth and torpor]] like imprisonment, restless and {{Wiki|worry}} like [[slavery]], and [[doubt]] like being lost on a desert road. [[Release]] from the [[hindrances]] is to be seen as freedom from debt, good [[health]], [[release]] from {{Wiki|prison}}, {{Wiki|emancipation}} from [[slavery]], and arriving at a place of safety (D.i,71-73). The second set of similes compares the [[hindrances]] to five kinds of [[impurities]] affecting a [[bowl]] of [[water]], preventing a keen-sighted man from [[seeing]] his [[own]] {{Wiki|reflection}} as it really is. [[Sensual desire]] is like a [[bowl]] of [[water]] mixed with brightly colored paints, [[ill will]] like a [[bowl]] of boiling [[water]], [[sloth and torpor]] like [[water]] covered by mossy [[plants]], [[restlessness]] and {{Wiki|worry}} like [[water]] blown into ripples by the [[wind]], and [[doubt]] like muddy [[water]]. Just as the keen-eyed man would not be [[able]] to see his {{Wiki|reflection}} in these five kinds of [[water]], so one whose [[mind]] is [[obsessed]] by the [[five hindrances]] does not know and see as it is his [[own]] good, the good of others or the good of both (S.v,121-24). Although there are numerous [[defilements]] opposed to the [[first jhana]] the [[five hindrances]] alone are called its factors of [[abandoning]]. One [[reason]] according to the [[Visuddhimagga]], is that the [[hindrances]] are specifically obstructive to [[jhana]], each [[hindrance]] impeding in its [[own]] way the [[mind's]] capacity for [[concentration]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[mind]] affected through [[lust]] by [[greed]] for varied [[objective]] fields does not become [[concentrated]] on an [[object]] consisting in {{Wiki|unity}}, or being overwhelmed by [[lust]], it does not enter on the way to [[abandoning]] the [[sense-desire]] [[element]]. When pestered by [[ill will]] towards an [[object]], it does not occur uninterruptedly. When overcome by stiffness and {{Wiki|torpor}}, it is unwieldy. When seized by [[agitation]] and {{Wiki|worry}}, it is unquiet and buzzes about. When stricken by uncertainty, it fails to mount the way to [[accomplish]] the [[attainment]] of [[jhana]]. So it is these only that are called factors of [[abandonment]] because they are specifically obstructive to jhana.(Vism.146: PP.152) | ||

| + | |||

| + | A second [[reason]] for confining the first jhana's factors of [[abandoning]] to the [[five hindrances]] is to permit a direct alignment to be made between the [[hindrances]] and the [[jhanic]] factors. [[Buddhaghosa]] states that the [[abandonment]] of the [[five hindrances]] alone is mentioned in connection with [[jhana]] because the [[hindrances]] are the direct enemies of the five [[jhana]] factors, which the [[latter]] must eliminate and abolish. To support his point the commentator cites a passage demonstrating a one-to-one [[correspondence]] between the [[jhana]] factors and the [[hindrances]]: [[one-pointedness]] is opposed to [[sensual desire]], [[rapture]] to [[ill will]], applied [[thought]] to [[sloth and torpor]], [[happiness]] to [[restlessness]] and {{Wiki|worry}}, and sustained [[thought]] to [[doubt]] (Vism. 141; PP.147).<ref>[[Buddhaghosa]] ascribes the passage he cites in support of the [[correspondence]] to the "Petaka," but it cannot be traced anywhere in the {{Wiki|present}} [[Tipitaka]], nor in the {{Wiki|exegetical}} work named [[Petakopadesa]].</ref> Thus each [[jhana]] factor is seen as having the specific task of eliminating a particular obstruction to the [[jhana]] and to correlate these obstructions with the five [[jhana]] factors they are collected into a scheme of [[five hindrances]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The standard passage describing the [[attainment]] of the [[first jhana]] says that the [[jhana]] is entered upon by one who is "secluded from [[sense]] [[pleasures]], secluded from [[unwholesome]] [[states of mind]]." The [[Visuddhimagga]] explains that there are three kinds of [[seclusion]] relevant to the {{Wiki|present}} context -- namely, [[bodily]] [[seclusion]] ([[kayaviveka]]), [[mental]] [[seclusion]] ([[cittaviveka]]), and [[seclusion]] by suppression ([[vikkhambhanaviveka]]) (Vism. 140; PP.145). These three terms allude to two {{Wiki|distinct}} sets of {{Wiki|exegetical}} categories. The first two belong to a threefold arrangement made up of [[bodily]] [[seclusion]], [[mental]] [[seclusion]], and "[[seclusion]] from the [[substance]]" ([[upadhiviveka]]). The first means [[physical]] withdrawal from active {{Wiki|social}} engagement into a [[condition]] of [[solitude]] for the {{Wiki|purpose}} of devoting [[time]] and [[energy]] to [[spiritual]] [[development]]. The second, which generally presupposes the first, means the [[seclusion]] of the [[mind]] from its entanglement in [[defilements]]; it is in effect {{Wiki|equivalent}} to [[concentration]] of at least the access level. The third, "[[seclusion]] from the [[substance]]," is [[Nibbana]], [[liberation]] from the [[elements]] of [[phenomenal existence]]. The [[achievement]] of the [[first jhana]] does not depend on the third, which is its outcome rather than prerequisite, but it does require [[physical]] [[solitude]] and the separation of the [[mind]] from [[defilements]], hence [[bodily]] and [[mental]] [[seclusion]]. The third type of [[seclusion]] pertinent to the context, [[seclusion]] by suppression, belongs to a different scheme generally discussed under the heading of "[[abandonment]]" ([[pahana]]) rather than "[[seclusion]]." The type of [[abandonment]] required for the [[attainment]] of [[jhana]] is [[abandonment]] by suppression, which means the removal of the [[hindrances]] by force of [[concentration]] similar to the pressing down of weeds in a pond by means of a porous pot.<ref>The other two types of [[abandoning]] are by substitution of opposites ([[tadangappahana]]), which means the replacement of [[unwholesome]] states by [[wholesome]] ones specifically opposed to them, and [[abandoning]] by eradication ([[samucchedappahana]]), the final destruction of [[defilements]] by the [[supramundane paths]]. See Vism.693-96;PP.812-16. </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The work of [[overcoming]] the [[five hindrances]] is accomplished through the [[gradual training]] ([[anupubbasikkha]]) which the [[Buddha]] has laid down so often in the [[suttas]], such as the [[Samannaphala Sutta]] and the [[Culahatthipadopama Sutta]]. The [[gradual training]] is a step-by-step process designed to lead the [[practitioner]] gradually to [[liberation]]. The {{Wiki|training}} begins with [[moral discipline]], the {{Wiki|undertaking}} and [[observance]] of specific {{Wiki|rules}} of conduct which enable the [[disciple]] to control the coarser modes of [[bodily]] and [[verbal]] {{Wiki|misconduct}} through which the [[hindrances]] find an outlet. With [[moral discipline]] as a basis, the [[disciple]] practices the {{Wiki|restraint}} of the [[senses]]. He does not seize upon the general [[appearances]] of the beguiling features of things, but guards and [[masters]] his [[sense faculties]] so that {{Wiki|sensual}} attractive and repugnant [[objects]] no longer become grounds for [[desire]] and [[aversion]]. Then, endowed with the self-restraint, he develops [[mindfulness]] and [[discernment]] ([[sati-sampajanna]]) in all his [[activities]] and [[postures]], examining everything he does with clear [[awareness]] as to its {{Wiki|purpose}} and suitability. He also cultivates [[contentment]] with a minimum of [[robes]], [[food]], [[shelter]] and other requisites. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Once he has fulfilled these preliminaries the [[disciple]] is prepared to go into [[solitude]] to develop the [[jhanas]], and it is here that he directly confronts the [[five hindrances]]. The elimination of the [[hindrances]] requires that the [[meditator]] honestly appraises his [[own]] [[mind]]. When [[sensuality]], [[ill will]] and the other [[hindrances]] are {{Wiki|present}}, he must [[recognize]] that they are {{Wiki|present}} and he must investigate the [[conditions]] that lead to their [[arising]]: the [[latter]] he must scrupulously avoid. The [[meditator]] must also understand the appropriate [[antidotes]] for each of the [[five hindrances]]. The [[Buddha]] says that all the [[hindrances]] arise through unwise [[consideration]] ([[ayoniso manasikara]]) and that they can be eliminated by [[wise]] [[consideration]] ([[yoniso manasikara]]). Each [[hindrance]], however, has its [[own]] specific antidote. Thus [[wise]] [[consideration]] of the repulsive feature of things is the antidote to [[sensual desire]]; [[wise]] [[consideration]] of [[loving-kindness]] counteracts [[ill will]]; [[wise]] [[consideration]] of the [[elements]] of [[effort]], {{Wiki|exertion}} and striving opposes [[sloth and torpor]]; [[wise]] [[consideration]] of [[tranquillity]] of [[mind]] removes [[restlessness]] and {{Wiki|worry}}; and [[wise]] [[consideration]] of the real qualities of things eliminates [[doubt]] (S.v,105-106). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Having given up covetousness [i.e. [[sensual desire]]) with regard to the [[world]], he dwells with a [[heart]] free of covetousness; he cleanses his [[mind]] from covetousness. Having given up the blemish of [[ill will]], he dwells without [[ill will]]; friendly and [[compassionate]] towards [[all living beings]], he cleanses his [[mind]] from the blemishes of [[ill will]]. Having given up [[sloth and torpor]], he dwells free from [[sloth and torpor]], in the [[perception]] of {{Wiki|light}}; [[mindful]] and clearly comprehending, he cleanses his [[mind]] from [[sloth and torpor]]. Having given up [[restlessness]] and {{Wiki|worry}}, he dwells without [[restlessness]]; his [[mind]] being [[calmed]] within, he cleanses it from [[restlessness]] and {{Wiki|worry}}. Having given up [[doubt]], he dwells as one who has passed beyond [[doubt]]; being free from uncertainty about [[wholesome]] things, he cleanses his [[mind]] from [[doubt]] .... | ||

| + | |||

| + | And when he sees himself free of these [[five hindrances]], [[joy]] arises; in him who is [[joyful]], [[rapture]] arises; in him whose [[mind]] is enraptured, the [[body]] is stilled; the [[body]] being stilled, he [[feels]] [[happiness]]; and a [[happy]] [[mind]] finds [[concentration]]. Then, quite secluded from [[sense]] [[pleasures]], secluded from [[unwholesome]] [[states of mind]], he enters and dwells in the [[first jhana]], which is accompanied by applied [[thought]] and sustained [[thought]], with [[rapture]] and [[happiness]] born of [[seclusion]]. (D.i,73-74)<ref>Adapted from [[Nyanaponika Thera]], The [[Five Mental Hindrances]] and Their Conquest ([[Wheel]] No. 26). This booklet contains a full compilation of texts on the [[hindrances]]. </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The Factors of the [[First Jhana]]=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[first jhana]] possesses five component factors: applied [[thought]], sustained [[thought]], [[rapture]], [[happiness]] and [[one-pointedness of mind]]. Four of these are explicitly mentioned in the [[formula]] for the [[jhana]]; the fifth, [[one-pointedness]], is mentioned elsewhere in the [[suttas]] but is already suggested by the notion of [[jhana]] itself. These five states receive their [[name]], first because they lead the [[mind]] from the level of ordinary [[consciousness]] to the [[jhanic]] level, and second because they constitute the [[first jhana]] and give it its {{Wiki|distinct}} [[definition]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[jhana]] factors are first aroused by the [[meditator's]] initial efforts to [[concentrate]] upon one of the prescribed [[objects]] for developing [[jhana]]. As he fixes his [[mind]] on the preliminary [[object]], such as a [[kasina]] disk, a point is eventually reached where he can {{Wiki|perceive}} the [[object]] as clearly with his [[eyes]] closed as with them open. This [[visualized]] [[object]] is called the {{Wiki|learning}} sign ([[uggahanimitta]]). As he [[concentrates]] on the {{Wiki|learning}} sign, his efforts call into play the embryonic [[jhana]] factors, which grow in force, duration and prominence as a result of the [[meditative]] {{Wiki|exertion}}. These factors, being incompatible with the [[hindrances]], attenuate them, exclude them, and hold them at bay. With continued practice the {{Wiki|learning}} sign gives rise to a [[purified]] {{Wiki|luminous}} replica of itself called the [[counterpart sign]] ([[patibhaganimitta]]), the [[manifestation]] of which marks the complete suppression of the [[hindrances]] and the [[attainment]] of [[access concentration]] ([[upacarasamadhi]]). All three events-the suppression of the [[hindrances]], the [[arising]] of the [[counterpart sign]], and the [[attainment]] of [[access concentration]] -- take place at precisely the same [[moment]], without {{Wiki|interval}} (Vism. 126; PP.131). And though previously the process of [[mental]] [[cultivation]] may have required the elimination of different [[hindrances]] at different times, when access is achieved they all subside together: | ||

| + | |||

| + | Simultaneously with his acquiring the [[counterpart sign]] his [[lust]] is abandoned by suppression owing to his giving no [[attention]] externally to [[sense desires]] (as [[object]]). And owing to his [[abandoning]] of approval, [[ill will]] is abandoned too, as pus is with the [[abandoning]] of {{Wiki|blood}}. Likewise stiffness and {{Wiki|torpor}} is abandoned through {{Wiki|exertion}} of [[energy]], [[agitation]] and {{Wiki|worry}} is abandoned through [[devotion]] to [[peaceful]] things that [[cause]] no {{Wiki|remorse}}; and uncertainty about the [[Master]] who teaches the way, about the way, and about the fruit of the way, about the way, and about the fruit of the way, is abandoned through the actual [[experience]] of the {{Wiki|distinction}} [[attained]]. So the [[five hindrances]] are abandoned. (Vism. 189; PP.196) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though the [[mental factors]] {{Wiki|determinative}} of the [[first jhana]] are {{Wiki|present}} in [[access concentration]], they do not as yet possess sufficient strength to constitute the [[jhana]], but are strong enough only to exclude the [[hindrances]]. With continued practice, however, the nascent [[jhana]] factors grow in strength until they are capable of issuing in [[jhana]]. Because of the instrumental role these factors play both in the [[attainment]] and constitution of the [[first jhana]] they are deserving of closer {{Wiki|individual}} {{Wiki|scrutiny}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Applied [[Thought]] ([[vitakka]])=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[word]] [[vitakka]] frequently appears in the texts in {{Wiki|conjunction}} with the [[word]] [[vicara]]. The pair signify two interconnected but {{Wiki|distinct}} aspects of the [[thought]] process, and to bring out the difference between them (as well as their common [[character]]), we translate the one as applied [[thought]] and the other as sustained [[thought]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In both the [[suttas]] and the [[Abhidhamma]] applied [[thought]] is defined as the application of the [[mind]] to its [[object]] ([[cetaso abhiniropana]]), a [[function]] which the [[Atthasalini]] illustrates thus: "Just as someone ascends the king's palace in [[dependence]] on a [[relative]] of [[friend]] dear to the [[king]], so the [[mind]] ascends the [[object]] in [[dependence]] on applied [[thought]]" (Dhs.A.157). This [[function]] of applying the [[mind]] to the [[object]] is common to the wide variety of modes in which the [[mental factor]] of applied [[thought]] occurs, ranging from [[sense]] {{Wiki|discrimination}} to [[imagination]], {{Wiki|reasoning}} and {{Wiki|deliberation}} and to the practice of [[concentration]] culminating in the [[first jhana]]. Applied [[thought]] can be [[unwholesome]] as in [[thoughts]] of [[sensual pleasure]], [[ill will]] and [[cruelty]], or [[wholesome]] as in [[thoughts]] of [[renunciation]], [[benevolence]] and [[compassion]] (M.i,116). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In [[jhana]] applied through is invariably [[wholesome]] and its [[function]] of directing the [[mind]] upon its [[object]] stands forth with special clarity. To convey this the [[Visuddhimagga]] explains that in [[jhana]] the [[function]] of applied [[thought]] is "to strike at and thresh -- for the [[meditator]] is said, in [[virtue]] of it, to have the [[object]] struck at by applied [[thought]], threshed by applied [[thought]]" (Vism.142;PP148). The [[Milindapanha]] makes the same point by defining applied [[thought]] as [[absorption]] ([[appana]]): "Just as a {{Wiki|carpenter}} drives a well-fashioned piece of [[wood]] into a joint, so applied [[thought]] has the [[characteristic]] of [[absorption]]" (Miln.62). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[object]] of [[jhana]] into which [[vitakka]] drives the [[mind]] and its [[concomitant]] states is the [[counterpart sign]], which emerges from the {{Wiki|learning}} sign as the [[hindrances]] are suppressed and the [[mind]] enters [[access concentration]]. The [[Visuddhimagga]] explains the difference between the two [[signs]] thus: | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the {{Wiki|learning}} sign any fault in the [[kasina]] is apparent. But the [[counterpart sign]] appears as if breaking out from the {{Wiki|learning}} sign, and a hundred times, a thousand times more [[purified]], like a looking-glass disk drawn from its case, like a mother-of-pearl dish well washed, like the [[moon's]] disk coming out from behind a cloud, like cranes against a [[thunder]] cloud. But it has neither {{Wiki|color}} nor shape; for if it had, it would be cognizable by the [[eye]], gross, susceptible of [[comprehension]] (by [[insight]]) and stamped with the [[three characteristics]]. But it is not like that. For it is born only of [[perception]] in one who has obtained [[concentration]], being a mere mode of [[appearance]] (Vism. 125-26; PP.130) | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[counterpart sign]] is the [[object]] of both [[access concentration]] and [[jhana]], which differ neither in their [[object]] nor in the removal of the [[hindrances]] but in the strength of their respective [[jhana]] factors. In the former the factors are still weak, not yet fully developed, while in the [[jhana]] they are strong enough to make the [[mind]] fully absorbed in the [[object]]. In this process applied [[thought]] is the factor primarily responsible for directing the [[mind]] towards the [[counterpart sign]] and thrusting it in with the force of full [[absorption]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Sustained [[Thought]] ([[vicara]])=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Vicara]] seems to represent a more developed phase of the [[thought]] process than [[vitakka]]. The commentaries explain that it has the [[characteristic]] of "continued pressure" on the [[object]] (Vim. 142; PP.148). Applied [[thought]] is described as the first impact of the [[mind]] on the [[object]], the gross inceptive phase of [[thought]]; sustained [[thought]] is described as the act of anchoring the [[mind]] on the [[object]], the {{Wiki|subtle}} phase of continued [[mental]] pressure. [[Buddhaghosa]] illustrates the difference between the two with a series of similes. Applied [[thought]] is like striking a [[bell]], sustained [[thought]] like the ringing; applied [[thought]] is like a bee's flying towards a [[flower]], sustained [[thought]] like its buzzing around the [[flower]]; applied [[thought]] is like a {{Wiki|compass}} pin that stays fixed to the center of a circle, sustained [[thought]] like the pin that revolves around (Vism. 142-43; PP.148-49). | ||

| + | |||

| + | These similes make it clear that applied [[thought]] and sustained [[thought]] functionally associated, perform different tasks. Applied [[thought]] brings the [[mind]] to the [[object]], sustained [[thought]] fixes and anchors it there. Applied [[thought]] focuses the [[mind]] on the [[object]], sustained [[thought]] examines and inspects what is focused on. Applied [[thought]] brings a deepening of [[concentration]] by again and again leading the [[mind]] back to the same [[object]], sustained [[thought]] sustains the [[concentration]] achieved by keeping the [[mind]] anchored on that [[object]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===[[Rapture]] ([[piti]])=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The third factor {{Wiki|present}} in the [[first jhana]] is [[piti]], usually translated as [[joy]] or [[rapture]].<ref>Ven [[Nanamoli]], in his translation of the [[Visuddhimagga]], renders [[piti]] by "[[happiness]]," but this rendering can be misleading since most [[translators]] use "[[happiness]]" as a rendering for [[sukha]], the [[pleasurable]] [[feeling]] {{Wiki|present}} in the [[jhana]]. We will render [[piti]] by "[[rapture]]," thus maintaining the connection of the term with {{Wiki|ecstatic}} [[meditative]] [[experience]]. </ref> In the [[suttas]] [[piti]] is sometimes said to arise from another [[quality]] called [[pamojja]], translated as [[joy]] or gladness, which springs up with the [[abandonment]] of the [[five hindrances]]. When the [[disciple]] sees the [[five hindrances]] abandoned in himself "gladness arises within him; thus gladdened, [[rapture]] arises in him; and when he is rapturous his [[body]] becomes [[tranquil]]" (D.i,73). [[Tranquillity]] in turn leads to [[happiness]], on the basis of which the [[mind]] becomes [[concentrated]]. Thus [[rapture]] precedes the actual [[arising]] of the [[first jhana]], but persists through the remaining stages up to the [[third jhana]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Vibhanga]] defines [[piti]] as "gladness, [[joy]], [[joyfulness]], mirth, merriment, [[exultation]], exhilaration, and [[satisfaction]] of [[mind]]" (Vbh. 257). The commentaries ascribe to it the [[characteristic]] of endearing, the [[function]] of refreshing the [[body]] and [[mind]] or pervading with [[rapture]], and the [[manifestation]] as {{Wikidictionary|elation}} (Vism.143; PP.149). [[Shwe Zan Aung]] explains that "[[piti]] abstracted means [[interest]] of varying degrees of intensity, in an [[object]] felt as desirable or as calculated to bring [[happiness]]."<ref>[[Shwe Zan Aung]], Compendium of [[Philosophy]] ({{Wiki|London}}: [[Pali Text Society]], 1960), p243. </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | When defined in terms of agency, [[piti]] is that which creates [[interest]] in the [[object]]; when defined in terms of its [[nature]] it is the [[interest]] in the [[object]]. Because it creates a positive [[interest]] in the [[object]], the [[jhana]] factor of [[rapture]] is [[able]] to counter and suppress the [[hindrance]] of [[ill will]], a [[state]] of [[aversion]] implying a negative {{Wiki|evaluation}} of the [[object]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Rapture]] is graded into five categories: minor [[rapture]], momentary [[rapture]], showering [[rapture]], uplifting [[rapture]] and pervading [[rapture]].<ref>[[Khuddhikapiti]], [[khanikapiti]], [[okkantikapiti]], [[ubbega piti]] and [[pharana piti]]. Vism 143-44; PP. 149-51. Dhs.A.158. </ref> Minor [[rapture]] is generally the first to appear in the progressive [[development]] of [[meditation]]; it is capable of causing the hairs of the [[body]] to rise. Momentary [[rapture]], which is like {{Wiki|lightning}}, comes next but cannot be sustained for long. Showering [[rapture]] runs through the [[body]] in waves, producing a thrill but without leaving a lasting impact. Uplifting [[rapture]], which can [[cause]] [[levitation]], is more sustained but still tends to disturb [[concentration]], The [[form]] of [[rapture]] most conductive to the [[attainment]] of [[jhana]] is all-pervading [[rapture]], which is said to suffuse the whole [[body]] so that it becomes like a full bladder or like a mountain cavern inundated with a mighty flood of [[water]]. The [[Visuddhimagga]] states that what is intended by the [[jhana]] factor of [[rapture]] is this all-pervading [[rapture]] "which is the [[root]] of [[absorption]] and comes by growth into association with [[absorption]]" (Vism.144; PP.151) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===[[Happiness]] ([[sukha]])=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | As a factor of the [[first jhana]], [[sukha]] {{Wiki|signifies}} [[pleasant]] [[feeling]]. The [[word]] is explicitly defined in the [[sense]] by the [[Vibhanga]] in its analysis of the [[first jhana]]: "Therein, what is [[happiness]]? [[Mental]] [[pleasure]] and [[happiness]] born of [[mind-contact]], the felt [[pleasure]] and [[happiness]] born of [[mind-contact]], [[pleasurable]] and [[happy]] [[feeling]] born of [[mind]] [[contact]] -- this is called '[[happiness]]' " (Vbh.257). The [[Visuddhimagga]] explains that [[happiness]] in the [[first jhana]] has the [[characteristic]] of gratifying, the [[function]] of intensifying associated states, and as [[manifestation]], the rendering of aid to its associated states (Vism. 145; PP.151). | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Rapture]] and [[happiness]] link together in a very close relationship, but though the two are difficult to distinguish, they are not [[identical]]. [[Happiness]] is a [[feeling]] ([[vedana]]);, [[rapture]] a [[mental formation]] ([[sankhara]]). [[Happiness]] always accompanies [[rapture]], so that when [[rapture]] is {{Wiki|present}} [[happiness]] must always be {{Wiki|present}}; but [[rapture]] does not always accompany [[happiness]], for in the [[third jhana]], as we will see, there is [[happiness]] but no [[rapture]]. The [[Atthasalini]], which explains [[rapture]] as "[[delight]] in the [[attaining]] of the [[desired]] [[object]]" and [[happiness]] as "the [[enjoyment]] of the {{Wiki|taste}} of what is required," illustrates the difference by means of a simile: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Rapture]] is like a weary traveler in the desert in summer, who hears of, or sees [[water]] of a shady [[wood]]. Ease ([[happiness]]) is like his enjoying the [[water]] of entering the {{Wiki|forest}} shade. For a man who, traveling along the [[path]] through a great desert and overcome by the heat, is thirsty and desirous of drink, if he saw a man on the way, would ask 'Where is [[water]]?' The other would say, 'Beyond the [[wood]] is a dense {{Wiki|forest}} with a natural [[lake]]. Go there, and you will get some.' He, hearing these words, would be glad and [[delighted]] and as he went would see [[lotus]] leaves, etc., fallen on the ground and become more glad and [[delighted]]. Going onwards, he would see men with wet [[clothes]] and [[hair]], hear the {{Wiki|sounds}} of wild fowl and pea-fowl, etc., see the dense {{Wiki|forest}} of [[green]] like a net of [[jewels]] growing by the edge of the natural [[lake]], he would see the [[water]] lily, the [[lotus]], the white lily, etc., growing in the [[lake]], he would see the clear transparent [[water]], he would be all the more glad and [[delighted]], would descend into the natural [[lake]], bathe and drink at [[pleasure]] and, his oppression being allayed, he would eat the fibers and stalks of the lilies, adorn himself with the [[blue lotus]], carry on his shoulders the [[roots]] of the mandalaka, ascend from the [[lake]], put on his [[clothes]], dry the [[bathing cloth]] in the {{Wiki|sun}}, and in the cool shade where the breeze blew ever so gently lay himself down and saw: 'O [[bliss]]! O [[bliss]]!' Thus should this illustration be applied. The [[time]] of gladness and [[delight]] from when he heard of the natural [[lake]] and the dense {{Wiki|forest}} till he say the [[water]] is like [[rapture]] having the [[manner]] of gladness and [[delight]] at the [[object]] in [[view]]. The [[time]] when, after his bath and dried he laid himself down in the cool shade, saying, 'O [[bliss]]! O [[bliss]]!' etc., is the [[sense]] of ease ([[happiness]]) grown strong, established in that mode of enjoying the {{Wiki|taste}} of the [[object]].<ref>Dhs.A.160-61. Translation by [[Maung Tin]], The [[Expositor]] ([[Atthasalini]]) ({{Wiki|London}}: [[Pali Text Society]], 1921), i.155-56. </ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Since [[rapture]] and [[happiness]] co-exist in the [[first jhana]], this simile should not be taken to imply that they are mutually exclusive. Its purport is to suggest that [[rapture]] gains prominence before [[happiness]], for which it helps provide a causal foundation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the description of the [[first jhana]], [[rapture]] and [[happiness]] are said to be "born of [[seclusion]]" and to suffuse the whole [[body]] of the [[meditator]] in such a way that there is no part of his [[body]] which remains unaffected by them: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Monks]], secluded from [[sense]] [[pleasure]] ... a [[monk]] enters and dwells in the [[first jhana]]. He steeps, drenches, fills and suffuses his [[body]] with the [[rapture]] and [[happiness]] born of [[seclusion]], so that there is no part of his entire [[body]] that is not suffused with this [[rapture]] and [[happiness]]. Just as a [[skilled]] bath-attendant or his apprentice might strew bathing powder in a {{Wiki|copper}} basin, sprinkle it again and again with [[water]], and knead it together so that the {{Wiki|mass}} of bathing soap would be pervaded, suffused, and saturated with [[moisture]] inside and out yet would not ooze [[moisture]], so a [[monk]] steeps, drenches, fills and suffuses his [[body]] with the [[rapture]] and [[happiness]] born of [[seclusion]], so that, there is no part of his entire [[body]] that is not suffused with this [[rapture]] and [[happiness]] born of [[seclusion]]. (D.i,74) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===[[One-pointedness]] ([[ekaggata]])=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Unlike the previous four [[jhana]] factors, [[one-pointedness]] is not specifically mentioned in the standard [[formula]] for the [[first jhana]], but it is included among the [[jhana]] factors by the [[Mahavedalla Sutta]] (M.i,294) as well as in the [[Abhidhamma]] and the commentaries. [[One-pointedness]] is a [[universal]] [[mental]] [[concomitant]], the factor by [[virtue]] of which the [[mind]] is centered upon its [[object]]. It brings the [[mind]] to a single point, the point occupied by the [[object]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[One-pointedness]] is used in the text as a {{Wiki|synonym}} for [[concentration]] ([[samadhi]]) which has the [[characteristic]] of non-distraction, the [[function]] of eliminating {{Wiki|distractions}}, non-wavering as its [[manifestation]], and [[happiness]] as its proximate [[cause]] (Vism.85; PP.85). As a [[jhana]] factor [[one-pointedness]] is always directed to a [[wholesome]] [[object]] and wards off [[unwholesome]] [[influences]], in particular the [[hindrance]] of [[sensual desire]]. As the [[hindrances]] are absent in [[jhana]] [[one-pointedness]] acquires special strength, based on the previous sustained [[effort]] of [[concentration]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Besides the five [[jhana]] factors, the [[first jhana]] contains a great number of other [[mental factors]] functioning in [[unison]] as coordinate members of a single [[state of consciousness]]. Already the [[Anupada Sutta]] lists such additional components of the [[first jhana]] as [[contact]], [[feeling]], [[perception]], [[Wikipedia:Volition (psychology)|volition]], [[consciousness]], [[desire]], [[decision]], [[energy]], [[mindfulness]], [[equanimity]] and [[attention]] (M.iii,25). In the [[Abhidhamma]] {{Wiki|literature}} this is extended still further up to [[thirty-three]] indispensable components. Nevertheless, only five states are called the factors of the [[first jhana]], for only these have the functions of inhibiting the [[five hindrances]] and fixing the [[mind]] in [[absorption]]. For the [[jhana]] to arise all these five factors must be {{Wiki|present}} simultaneously, exercising their special operations: | ||

| + | |||

| + | But applied [[thought]] directs the [[mind]] onto the [[object]]; sustained [[thought]] keeps it anchored there. [[Happiness]] ([[rapture]]) produced by the [[success]] of the [[effort]] refreshes the [[mind]] whose [[effort]] has succeeded through not being distracted by those [[hindrances]]; and [[bliss]] ([[happiness]]) intensifies it for the same [[reason]]. Then unification aided by this directing onto, this anchoring, this refreshing and this intensifying, evenly and rightly centers the [[mind]] with its remaining associated states on the [[object]] consisting in {{Wiki|unity}}. Consequently possession of five factors should be understood as the [[arising]] of these five, namely, applied [[thought]], sustained [[thought]], [[happiness]] ([[rapture]]), [[bliss]] ([[happiness]]), and unification of [[mind]]. For it is when these are arisen that [[jhana]] is said to be arisen, which is why they are called the five factors of possession. (Vism.146;PP.152) | ||

| + | |||

| + | Each [[jhana]] factor serves as support for the one which succeeds it. Applied [[thought]] must direct the [[mind]] to its [[object]] in order for sustained [[thought]] to anchor it there. Only when the [[mind]] is anchored can the [[interest]] develop which will culminate in [[rapture]]. As [[rapture]] develops it brings [[happiness]] to maturity, and this [[spiritual]] [[happiness]], by providing an alternative to the fickle [[pleasures]] of the [[senses]], aids the growth of [[one-pointedness]]. In this way, as [[Nagasena]] explains, all the other [[wholesome]] states lead to [[concentration]], which stands at their head like the apex on the roof of a house (Miln. 38-39). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Perfecting the [[First Jhana]]=== | ||