A Situation of Transmission

He's back! The same as before: when he arrives in the Institute at his rhythmic and peaceful step, hands joined and smiling at each of us, there is no detail in excess and nothing missing either. Lama Nyigyam expresses and allows us to experience equanimity. He has no need to seduce anyone, and he does not adapt the teachings; he transmits it. His presence has nothing sentimental about it. He is here to transmit the Dharma through his speech and his example.

Furthermore, once he is seated on the throne and he has recited the introductory prayers, he begins without tangent, “I will teach the daily practice of Chod based on the commentary of Lodro Thaye. The root of all suffering is self-grasping and the goal of Chod practice is to cut off self-grasping.” So that's said. The 180 people present are naturally placed in a situation of transmission. The teacher has the commentary in front of him and reads syllable after syllable, adding words and bits of sentences that make up the key instructions for the transmission to his reading.

Julie, the translator, is still refining her craft but quite efficient. She is alert, misses nothing, notes every addition, and asks for clarification. This takes a bit of time but the slow rhythm allows each of us to settle into the instructions given and we all know that the back-and-forth is a guarantee of precision.

The sessions continue one after another (four each day: two in the morning and two in the afternoon); at times a teaching; at times practice; at times guided meditation. And so will go the seven days of the retreat. With the exception of the afternoon of the second day, which is dedicated to the transmission of the empowerment.

With Lama Nyigyam and his way of doing things, eras cross over one another. The transmission of Chod began with Machigma in Tibet in the eleventh century; it continues up to the 3rd Karmapa Rangjung Dorje in the fourteenth century. It was he who integrated Chod practice into the Kagyu lineage. From there, several lineages took form: the one we receive today is the transmission of Surmang monastery, the seat of the Trungpa lineage, which is still living.

Crossing over: What we receive today was given in the same way several centuries ago, with the same essence. What characterizes this specific transmission? The instructions given are profound and extensive, the transmission is uninterrupted, and the blessings are intact. This is what creates a situation of transmission: the teaching is authentic and the teacher is qualified. All that is left for us, as listeners, is to bring together the conditions as recipients to listen with the required motivation and a fertile presence.

Chod benefits from all projections and all fantasies. When we talk about a practice that subjugates demons, imagination easily takes hold from there. However, from the beginning, Machigma herself, the founder of the Chod transmission, tells us, “What we call demons are not materially existing entities with giant, black forms that frighten and terrorize whoever sees them; we call demons those things that hinder us from reaching liberation.” So that's what is said. On this basis, we can approach Chod practice in a more healthy manner.

If we have to summarize what these demons are, the word “grasping” pretty much covers it: grasping sense objects (all that is external to us) or grasping states of mind (all that happens within us) or grasping what validates us and what brings us bliss, or, lastly, the grasping that causes all the others, self-grasping. Such are the four demons or four mara. Now we just have to ask ourselves what “grasping” means: it is an occurrence of the mind that consists on making something exist that does not; of solidifying what is transient; of rendering concrete what has no substance. It is this process of grasping that deceives us, that tricks us and that is the cause of so much suffering without any real reason. That is the irony of samsara: so much difficulty, so much pain for nothing. Naropa said, “It is not phenomena that are the problem but the attachment to these phenomena and the belief in their permanent existence.” This grasping is precisely the target of Chod practice.

Finally, there is the ritual form of the practice: a drum and a bell; the most intoxicating melodies; improbable, repeated sounds (pet!). Even if we understand the meaning, there is still a chance of being deluded by the ritual aspects. But Chod does not let itself get fooled around with.

As this practice was originally part of its own lineage entirely, it had its own vocabulary, its own references, its own codes, and yet, beyond codes, we find the view and the conduct of the most profound Dharma.

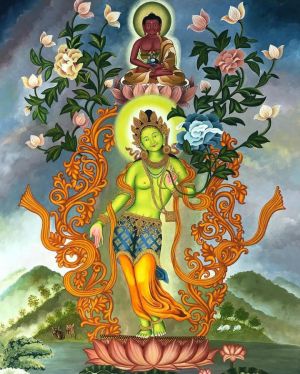

The goal of Chod is the realization of the Great Mother, Yum Chenmo in Tibetan, the mother of all Buddhas. What is this? The Great Mother is the emptiness by which each of us can realize Buddhahood. It is the most intimate thing within us; it has always been there. How do we reveal Yum Chenmo; how do we actualize emptiness? You guessed it!

Here's what Lama Nyigyam says at moment when he leaves the commentary aside and gives us the oral instructions, “If the mind is agitated, it cannot perceive its own nature. The moon cannot reflect in dirty, polluted water. We must dissipate the pollution, and calm the mind with the meditation of calm abiding. The moon can reflect on clear water; a peaceful mind can recognize its true nature, the truth of the Great Mother.” And on the basis of pacifying the mind, we can practice profound vision

(lhagtong), which definitively dissipates self-grasping, the cause of all demons. The Lama continues, “We pacify the mind, and then we contemplate what remains: calm mind and what arises in this mind; they have the same essence. We thus experience wisdom free from all fixation. In this space of wisdom, there is neither myself, nor other. This is where we come into contact with the truth of the Great Mother. Perceiving the absence of essence is seeing the Great Mother. It is mind that recognizes itself.” The true demon is thus liberated, that of dualistic grasping. The other demons then dissolve themselves.

The Quintessence of Chod

Lama Nyigyam invites us to meditate together to conclude the seven days of retreat. He gives meditation instructions, “To practice the true meaning of Chod and reveal the truth of the Great Mother (Mahamudra, emptiness, Buddhahood), we must pacify the mind using different methods to reach a state free of grasping concepts. Whatever concepts arise—pleasant or unpleasant, we must let them arise and recognize them; they all have the same nature. They have no true existence.

Through observation, instantaneous vision, we recognize concepts' absence of essence. When a thought arises, whether it is about the past, present, or future, we continue as if nothing had happened. There is nothing to add, such as, 'I'm thinking about it and that's not good, etc.' Facing what arises, we do not create anything; there is nothing to meditate. We do not give any importance to what arises by asking, 'Is it there or isn't it? Is it like this or like that?'

It is pointless to say, “We must meditate on this or on that, etc.” Whatever concept arises, we let it arise and we do not grasp it. If we can rest in this state, that is excellent. If not, we meditate on a support that helps us to pacify the mind.” The meditative silence that followed was filled with these instructions. We were happy with the fulfillment of this week of retreat, at once rich and at times trying. We were all grateful that such Dharma can still be transmitted today, for us.

If we look closely, we see that whether it's Chod, a meditation retreat, instructions on the four objects of mindfulness, or a course on impermanence, the goal is the same: to nourish discernment that clarifies and activate compassion that liberates. Here, what set this apart was the presence of an authentic practitioner: Lama Nyigyam. During a discussion, we asked him if he had completely renounced samsara or not when he took his monk's vows at age twenty-six years. He replied with conviction as

though it had been evident to him, and without an ounce of pride. He looked us right in the eyes to make sure there was no doubt, “Yes.” It sounded like, “Obviously.” This is what makes the strength of a true practitioner; this certainty born of conviction. This conviction that comes from meditation. Meditation based on reflection. Reflection rooted in the study of the Buddha's teaching. Then, all that remains is to help others do the same, as the Buddha did.

Saving Lives

Chod is a practice of generosity. It is in fact the most noble form of generosity because we offer our own bodies, that which we hold dearest, the basis of identification with a self. As we are not capable of truly doing so, we meditate in this way and symbolically carry it out through visualizations that were of course greatly taught during the retreat. To conclude the week with another act of generosity seemed only logical: life release practice.

Doubtless, we are all familiar with the words of Chatral Rinpoche:

“Consider each life as if it were your own body,

And make an effort not to kill any living creature,

Birds, fish, deer, cattle, and even tiny insects,

And task yourself instead with saving lives

By offering protection against every danger.”

Dhagpo's team organized a rescue of 8,000 crickets destined to be devoured by pet reptiles. At the end of the final session, we came together around the animals (lined up in little boxes, so we could each carry them off and free them in the best possible conditions). Jigme Rinpoche, back from the US the previous day, joined us for the occasion.

After a week of immersion in the highest tantras, instructions on Mahamudra and other rituals equally exotic in form, it felt good to concretely save lives. Thus concluded the retreat with Lama Nyigyam. He left at noon for Nice. We carried out a great offering feast that afternoon. An offering of gratitude, for there is no reason to halt the generosity.

Source

[[1]]