A Zen Nazi in Wartime Japan: Count Dürckheim and his Sources—D.T. Suzuki, Yasutani Haku’un and Eugen Herrigel

A Zen Nazi in Wartime Japan: Count Dürckheim and his Sources—D.T. Suzuki, Yasutani Haku’un and Eugen Herrigel

戦中日本におけるあるナチス禅宗徒 デュルクハイム伯爵の情報源 鈴木大拙、安谷白雲、オイゲン・ヘリゲル

Brian Daizen Victoria

Introduction

By the late 1930s Japan was well on the way to becoming a totalitarian society. True, in Japan there was no charismatic dictator like Hitler or Mussolini, but there was nevertheless a powerful “divine presence,” i.e., Emperor Hirohito.

Although seldom seen and never heard, he occasionally issued imperial edicts, serving to validate the actions of those political and military figures claiming to act on his behalf.

At least in theory, such validation was absolute and leftwing challenges to government policies, whether on the part of Communists, socialists or merely liberals, were mercilessly suppressed. For example, between 1928 and 1937 some 60,000 people were arrested under suspicion of harboring “dangerous thoughts,” i.e., anything that could conceivably undermine Japan’s colonial expansion abroad and repressive domestic policies at home. Added to this was the fact that Japan had begun its full-scale invasion of China on July 7, 1937.

Japan’s relationship with Germany was in flux according to the changing political interests of both countries.[1] Because of negative international reactions to the Anti-Comintern pact of November 1936, resistance against it increased in Japan soon after it was made, and the Japanese froze their policy of closer ties. However, in 1938 it became clear to Japan that the war against China would last longer than expected.

Thus, Japanese interest in a military alliance with Germany and Italy reemerged. On the German side, Joachim von Ribbentrop]] had become Foreign Minister in February 1938, and as he had long been a proponent of closer ties with Japan, negotiations between the two countries resumed in the summer of 1938.

Count Karlfried Dürckheim´s first Japan trip was probably connected with the beginning of this thaw in German-Japanese relations.

The birth of “total war” in the wake of World War I and even earlier had demonstrated that victory could not be achieved without the strong support and engagement of civilian populations, one aspect of which was not simply knowledge of potential adversaries but of one’s allies as well.

This meant enhanced cultural relations and mutual understanding between the citizens of allied nations.

It was under these circumstances that Dürckheim undertook what was portrayed as an education-related mission to Japan, a mission that would impact on him profoundly for the remainder of his life.

This was not the first such mission Dürckheim had undertaken on behalf of Foreign Minister Von Ribbentrop and Education Minister Bernhard Rust, for he had previously made somewhat similar trips to other countries, including South Africa and Britain. Dürckheim’s trip to South Africa took place from May thru October 1934 on behalf of Rust.

He conducted research on the cultural, political and educational situation of Germans in South Africa while at the same time promoting the new regime.

During his work in Ribbentrop’s office from 1935 to 1937, Dürckheim was a frequent visitor to Britain, around 20 times altogether. His task was to gather information about the image of National Socialism in Britain while at the same time promoting the “new Germany.”

Toward this end, he met such notables as King Edward VII and Winston Churchill and arranged a meeting between Hitler and Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Evening Standard. This was part of Hitler’s ultimately unsuccessful plan to form a military alliance with Britain directed against the Soviet Union. Dürckheim’s work officially ended on December 31, 1937.

Dürckheim’s First Visit to Japan

Dürckheim began his journey to Japan on June 7, 1938 and did not return to Germany until early 1939. According to his biographer, Gerhard Wehr, Dürckheim initially received a research assignment from the German Ministry of Education that consisted of two tasks:

first, to describe the development of Japanese national education including the so-called social question,[2] and second, to investigate the possibility of using cultural activities to promote Germany’s political aims both within Japan and those areas of Asia under Japanese influence.[3] Dürckheim arrived by boat and travelled extensively within Japan as well as undertaking trips to Korea, Manchukuo (Japan’s puppet state in Manchuria) and northern China. During his travels Dürckheim remained in close contact with the local NSDAP (Nazi) offices and the Japan-based division of the National Socialist Teachers Association.

Dürckheim Meets D.T. Suzuki

Dürckheim described his arrival in Japan as follows:

- I was sent there in 1938 with a particular mission that I had chosen: to study the spiritual background of Japanese education. As soon as I arrived at the embassy, an old man came to greet me. I did not know him. “Suzuki,” he stated. He was the famous Suzuki who was here to meet a certain Mister Dürckheim arriving from Germany to undertake certain studies.

- Suzuki is one of the greatest contemporary Zen Masters. I questioned him immediately on the different stages of Zen. He named the first two, and I added the next three.

Then he exclaimed: "Where did you learn this?" "In the teaching of Meister Eckhart!" "I must read him again...” (though he knew him well already). . . . It is under these circumstances that I discovered Zen. I would see Suzuki from time to time.[4]

Although the exact sequence of events leading up to their meeting is unknown, a few points can be surmised.

First, while Dürckheim states he had been sent to Japan on an educational mission, specifically to study “the spiritual foundations of Japanese education,”[5] it should be understood that within the context of Nazi ideology, education referred not only to formal academic,

classroom learning but, more importantly, to any form of “spiritual training/discipline” that produced loyal citizens ready to sacrifice themselves for the fatherland. Given this, it is unsurprising that following Dürckheim’s return to Germany in 1939 the key article he wrote was entitled “The Secret of Japanese Power” (Geheimnis der Japanisher Kraft).

Additionally, it should come as no surprise to read that Dürckheim was clearly aware of, and interested in, Suzuki’s new book. Wehr states: “In records from his first visit [to Japan) Dürckheim occasionally mentions Zen including, among others, D. T. Suzuki’s recently published book, Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture. In this connection, Dürckheim comments:

‘Zen is above all a religion of will and willpower; it is profoundly averse to intellectual philosophy and discursive thought, relying, instead, on intuition as the direct and immediate path to truth.’”[6] [[File:DTSUSUKI22.jpg|thumb|left|250px|D.T. Suzuki)]

In claiming this is it possible that Dürckheim had misunderstood the import of Suzuki’s writings? That is to say, had he in fact begun what might be called the ‘Nazification’ of Zen, i.e., twisting it to fit the ideology of National Socialism. In fact he had not, for in his 1938 book, Suzuki wrote: “Good fighters are generally ascetics or stoics, which means to have an iron will. When needed Zen supplies them with this.”[7] Suzuki futher explained:

"From the philosophical point of view, Zen upholds intuition against intellection, for intuition is the more direct way of reaching the Truth...Besides its direct method of reaching final faith, Zen is a religion of will-power, and will-power is what is urgently needed by the warriors, though it ought to be enlightened by intuition."[8]

In light of these quotes, and many others like them, whatever other faults the wartime Dürckheim may have had, misunderstanding Suzuki’s explication of Zen was not one of them.

And, significantly, Suzuki was not content in his book to simply link Zen as a religion of will to Japanese medieval warriors. He was equally intent to show that the same self-sacrificial, death-embracing spirit of the samurai had become the modern martial spirit of the Japanese people as a whole:

- The Japanese may not have any specific philosophy of life, but they have decidedly one of death which may sometimes appear to be that of recklessness.

The spirit of the samurai deeply breathing Zen into itself propagated its philosophy even among the masses. The latter, even when they are not particularly trained in the way of the warrior, have imbibed his spirit and are ready to sacrifice their lives for any cause they think worthy.

This has repeatedly been proved in the wars Japan has so far had to go through for one reason or another. A foreign writer on Japanese Buddhism aptly remarks that Zen is the Japanese character.[9]

Given these words, Dürckheim could not fail to have been interested in learning more about a Zen tradition that had allegedly instilled death-embracing values into the entire Japanese people. Hitler himself is recorded as having lamented, “You see, it’s been our misfortune to have the wrong religion.

Why didn’t we have the religion of the Japanese, who regard sacrifice for the Fatherland as the highest good?”[10] Thus Dürckheim’s mission may best be understood as unlocking the secret of the Japanese people’s power as manifested in the Zen-Bushidō ideology Suzuki promoted. No doubt, his superiors were deeply interested in duplicating, within the context of a German völkisch faith, this same spirit of unquestioning sacrifice for the Fatherland.

It is unlikely that Dürckheim had read Suzuki’s book prior to his arrival. Written in English, the Eastern Buddhist Society of Ōtani College didn’t publish it in Japan until May 1938. Suzuki reports that he first received copies of his book on May 20, 1938.[11]

This suggests that it was Embassy personnel, knowing of Dürckheim’s interests and Suzuki’s reputation, who requested Suzuki’s presence. Yet another possibility is that Dürckheim had heard about Suzuki during his frequent trips to Britain, since much of the material in Suzuki’s 1938 book consisted of lectures first delivered in Britain in 1936.

It is noteworthy that the first conversation between the two men centered on Meister Eckhart, the thirteenth century German theologian and mystic. On the surface this exchange seems totally innocuous, the very antithesis of Nazism. Yet, as discussed in Part II, Meister Eckhart was the embodiment of one major current in Nazi spirituality.

That is to say, within German völkisch religious thought Eckhart represented the very essence of a truly Germanic faith. [[File:Meister-Eckhart.jpg|thumb|250px|Meister Eckhart]]

Meister Eckhart's reception in Germany had undergone many changes over time, with Eckhart becoming linked to German nationalism by the early 19th century as a result of Napoleon's occupation of large parts of Germany. Many romanticists and adherents of German idealism regarded [[Wikipedia:

Meister Eckhart|Eckhart]] as a uniquely German mystic and admired him for having written in German instead of Latin and daring to oppose the Latin speaking world of scholasticism and the hierarchy of the Catholic Church.

In the 20th century, National Socialism - or at least some leading National Socialists - appropriated Eckhart as an early exponent of a specific Germanic Weltanschauung.

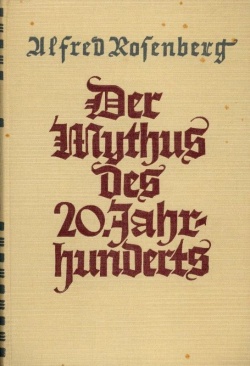

In particular, Alfred Rosenberg regarded Eckhart as the German mystic who had anticipated his own ideology and thus represented a key figure in Germanic cultural history. As a result, Rosenberg included a long chapter on Eckhart, entitled "Mysticism and Action,” in his book The Myth of the Twentieth Century.

Rosenberg was one of the Nazi’s chief ideologists and The Myth of the Twentieth Century was second in importance only to Hitler’s Mein Kampf. By 1944 more than a million copies had been sold. Rosenberg was attracted to Eckhart as one of the earliest exponents of the idea of “will” as supreme:

- Reason perceives all things, but it is the will, Eckhart comments, which can do all things. Thus where reason can go no further, the superior will flies upward into the light and into the power of faith. Then the will wishes to be above all perception. That is its highest achievement.[12]

Suzuki would no doubt have readily agreed with these sentiments, for, as we have already seen, he, too, placed great emphasis on will, identifying it as the very essence of Zen.

Rosenberg also included this almost Zen-like description of “Nordic Germanic man”:

- Nordic Germanic man is the antipode of both directions, grasping for both poles of our existence, combining mysticism and a life of action, being borne up by a dynamic vital feeling, being uplifted by the belief in the free creative will and the noble soul. Meister Eckhart wished to become one with himself. This is certainly our own ultimate desire.[13]

This said, the fact that there were similarities between Rosenberg’s description of Eckhart and Suzuki’s descriptions of Zen by no means demonstrates that Suzuki’s interest in Eckhart was identical with Rosenberg’s racist or fascist interpretation. In fact, Suzuki’s interest in Eckhart can be traced back to his interest in Theosophy in the 1920s.

Nevertheless, there is a clear and compelling parallel in the totalitarian nature of völkisch Nazi thought as represented by Rosenberg, as well as Dürckheim, and Suzuki’s own thinking.

As pointed out in Part II, one of the key components of Nazi thought was that “individualism” was an enemy that had to be overcome in order for the “parts” (i.e., a country’s citizens) to be ever willing to sacrifice themselves for the Volk, i.e., the “whole,” as ordered by the state.

Rudolph Hess, Hitler’s Deputy Führer, not only recognized the importance of this struggle but also admitted that the Japanese were ahead of the Nazis in this respect. Hess wrote:

- We, too, [like the Japanese) are battling to destroy individualism. We are struggling for a new Germany based on the new idea of totalitarianism. In Japan this way of thinking comes naturally to the people.[14]

Just how “naturally” (or even whether) the Japanese people rejected individualism and embraced totalitarianism is open to debate. Yet, we find Suzuki adopting an analogous position beginning with the publication of his very first book in 1896, i.e., Shin Shūkyō-ron (A Treatise on the New [Meaning of] Religion). Suzuki wrote:

- At the time of the commencement of hostilities with a foreign country, then marines fight on the sea and soldiers fight in the fields, swords flashing and cannon-smoke belching, moving this way and that.

In so doing, our soldiers regard their own lives as being as light as goose feathers while their devotion to duty is as heavy as Mt. Tai in China. Should they fall on the battlefield they have no regrets. This is what is called “religion in a national emergency.”[15]

Suzuki was only twenty-six years old when he wrote these lines, i.e., long before the emergence of the Nazis. Yet, he anticipated the Nazi’s demand that in wartime all citizens must discard attachment to their individual well-being and be ever ready to sacrifice themselves for the state, regarding their own lives “as light as goose feathers.”

During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, Suzuki exhorted Japanese soldiers as follows: “Let us then shuffle off this mortal coil whenever it becomes necessary, and not raise a grunting voice against the fates. . . .

Resting in this conviction, Buddhists carry the banner of Dharma over the dead and dying until they gain final victory.”[16]

Given these sentiments there clearly was no need for the Nazis to inculcate völkisch values, emphasizing self-sacrifice for the state, into Suzuki’s thought, for they had long been present.

In any event, the content of the initial conversation between Suzuki and Dürckheim does suggest why, from the outset, these two men found they shared so much in common. For his part, like “Nordic man” in the preceding quotation, Suzuki frequently equated Zen with the Japanese character.[17] In other words, within one of the two major strands of Nazi religiosity, Dürckheim would perhaps have understood, and welcomed, Suzuki as a völkisch proponent of a religion, i.e., Zen, dedicated to, and shaped by, the Japanese Volk. This may well explain what initially drew the two men together and led to their ongoing relationship.

It should also be noted that Suzuki was not the first to recognize affinities between Eckhart and Buddhism. In the 19th century the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer had postulated this connection. He wrote:

- If we turn from the forms, produced by external circumstances, and go to the root of things, we shall find that Buddha Shākyamuni and Meister Eckhart teach the same thing; only that the former dared to express his ideas plainly and positively, whereas [[Wikipedia:

Meister Eckhart|Eckhart]] is obliged to clothe them in the garment of the Christian myth, and to adapt his expressions thereto.[18]

As for Dürckheim, his interest in Eckhart, as noted in Part II, can be traced back to the 1920s when he began to practice meditation together with his friend Ferdinand Weinhandl, the Austrian philosopher who later became a professor in Kiel and another strong proponent of National Socialism.

Additionally, the Swiss psychologist C. G. Jung identified Eckhart as the most important thinker of his time.

Suzuki’s View of Nazi Germany

There is one vital question that warrants our attention, i.e., why had Suzuki accepted an invitation to come to a German Embassy so firmly under Nazi control? In the context of the times, this may not seem so surprising, but it is in fact a very surprising turn of events.

Very surprising, that is, if one believes the testimony of Satō Gemmyō Taira, a Shin (True Pure Land) Buddhist priest who, readers of Part I of this article will recall, identifies himself as one of Suzuki’s disciples in the postwar period.

Satō claims:

- Although Suzuki recognized that the Nazis had, in 1936, brought stability to Germany and although he was impressed by their youth activities (though not by the militaristic tone of these activities), he clearly had little regard for the Nazi leader, disapproved of their violent attitudes, and opposed the policies espoused by the party. His distaste for totalitarianism of any kind is unmistakable.[19]

If, as Satō asserts, Suzuki “opposed the policies espoused by the [[[Wikipedia:Nazi|Nazi]]] party,” etc. why would he have a

Source

- ↑ For the development of the political relationship between Germany and Japan, see Krebs, Gerhard. “Von Hitlers Machtübernahme zum Pazifischen Krieg (1933-1941)“ in Krebs, Gerhard / Martin, Bernd (ed.): Formierung und Fall der Achse Berlin-Tokyo. München: Iudicium 1994, pp. 11-26.

- ↑ The term “social question“ usually refers to all of the social wrongs connected to the industrial revolution, especially the emergence of class struggles that threaten the unity of a society. In Germany, the concept of “Volksgemeinschaft“ (a community of the people) was promoted as the Nazi alternative to deep divisions within modern society. Thus, the Nazis were interested in learning how their Anti-Comintern partner Japan dealt with this issue.

- ↑ Wehr, “Graf Durkheim Becoming Real.pdf The Life and Work of Karlfried Graf Durckheim.” Available on the Web. (accessed October 23, 2013).

- ↑ Goettmann, The Path of Initiation: An Introduction to the Life and Thought of Karlfried Graf Durckheim, p. 29.

- ↑ Wehr, “Graf Durkheim Becoming Real.pdf The Life and Work of Karlfried Graf Durckheim.” Available on the Web. (accessed October 23, 2013).

- ↑ Wehr, Karlfried Graf Dürckheim. Ein Leben im Zeichen der Wandlung, p. 96.

- ↑ Suzuki, Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture, p.35

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 34-37.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 64-65.

- ↑ Speer, Inside the Third Reich, p.96.

- ↑ Suzuki, “English Diaries,” No. 25, 2011, p. 60.

- ↑ Rosenberg, The Myth of the Twentieth Century, p. 55.

- ↑ Rosenberg, The Myth of the Twentieth Century, frontispiece.

- ↑ Quoted in Victoria, Zen War Stories, frontispiece. See Otto Tolischus, Tokyo Record.

- ↑ Quoted in Victoria, Zen at War, p. 25.

- ↑ Suzuki, “A Buddhist View of War.” Light of Dharma 4, 1904, pp. 181–82.

- ↑ See, for example, Suzuki’s frequent references to the identity of Zen and Japanese character in “Zen as a Cult of Death in the Wartime Writings of D.T. Suzuki.” Available on the Web.

- ↑ Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, Vol 2, Ch. XLVIII.

- ↑ Satō, “Brian Victoria and the Question of Scholarship,” p. 150.