A study of rain deities and rain wizards of Japan

In James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, at p. 73a he writes of a Japanese rain ritual of sacrifice dedicated to the dragon divinity:

“Among the high mountains of Japan there is a district in which, if rain has not fallen for a long time, a party of villagers goes in procession to the bed of a mountain torrent, headed by a priest, who leads a black dog. At the chosen spot they tether the beast to a stone, and make it a target for their bullets and arrows. When its life-blood bespatters the rocks, the peasants throw down their weapons and lift up their voices in supplication to the dragon divinity of the stream, exhorting him to send down forthwith a shower to cleanse the spot from its defilement. Custom has prescribed that on these occasions the colour of the victim shall be black, as an emblem of the wished-for rain-clouds. But if fine weather is wanted, the victim must be white, without a spot.“

In another passage of the same book by the author,

“In a Japanese village, when the guardian divinity had long been deaf to the peasants’ prayers for rain, they at last threw down his image and, with curses loud and long, hurled it head foremost into a stinking rice-field. “There,” they said, “you may stay yourself for a while, to see how you will feel after a few days’ scorching in this broiling sun that is burning the life from our cracking fields.” In the like circumstances the Feloupes of Senegambia cast down their fetishes and drag them about the fields, cursing them till rain falls.”

White horse-black horse and horse ema offerings

Kifune-jinja in Sakyo-ku, Kyoto (pictured above) is the headquarters for around 500 other Kifune shrines located across the country. Built some 1,600 years ago, the shrine’s legend has it that the goddess Tamayori-hime appeared on a yellow boat in Osaka Bay and said, “Build a sanctuary at the place where this boat stops and deify the spirit of the locality, and the country will prosper.” The boat floated up the rivers of the Yodo-gawa to the Kamo-gawa, stopping at the head of the stream. The deities enshrined here are Takaokami-no-Kami and Kuraokami-no-Kami. They are believed to be the gods of water, and people pray to them for rain during times of drought, and to stop rain during floods. A certain emperor dedicated a black horse in a drought, and a white horse during a prolonged spell of rain. This is why people now offer up votive plates with the image of a horse which are called “ema” (literally “picture horses”). (Source: Kifune-jinja, Kyoto)

Water spirits and dragon tutelary deities

Kuraokami no Kami and Takaokami no Kami are believed to be the same god, or a pair of gods, and Okami no Kami is considered the generic name, according to the Encyclopedia of Shinto

Kuraokami, Takaokami, Kuramitsuha, Encyclopedia of Shinto

(Nihongi)

Other names: Kuraokami no kami, Takaokami no kami(Kojiki)

Kami produced from the blood that dripped from Izanagi’s sword when he killed the kami of fire, Kagutsuchi. When Izanagi’s consort Izanami gave birth to the kami of fire, she was burned and died. Enraged and saddened at the loss of his wife, Izanagi beheaded Kagutsuchi with his “ten-span sword,” and numerous deities were produced from Kagutsuchi’s blood. According to Kojiki, Kuraokami and Kuramitsuha were produced from the blood as it collected on the hilt of Izanagi’s sword and dripped through his fingers. According to an “alternate writing” related by Nihongi, Izanagi killed Kagutsuchi by cutting him into three pieces, thus creating the three kami Ikazuchi no kami, Ōyamatsumi, and Takaokami. The word kura is said to mean a narrow gorge beneath a cliff, while okami refers to the dragon tutelary of water, and mitsuha suggests the water as it begins to emerge, or a water-spirit.- Yumiyama Tatsuya

The word kura is said to mean a narrow gorge beneath a cliff, while okami refers to the dragon tutelary of water, and mitsuha suggests the water as it begins to emerge, or a water-spirit.

Rain doctors and rain-making mountains

Afuri jinja People in Kanagawa and western Tokyo believed that if the top of the mountain was veiled by clouds, it would rain momentarily. During a long spell of dry weather, they offered a prayer and petition for rainfall to Sekison enshrined at the top of the mountain as if Sekison had been a rain doctor. Hence the Shrine was called Afurisan, or rainmaker-mountain. Incidentally, the present nameAfuri of Afuri Jinja is also short for a rainfall in Japanese.

In the early times, there was a shrine called Sekison atop Mt. Oyama, which is 1252 meters above sea level, enshrining a natural, giant and holy stone* as its principal object of worship. (Seki is a stone and son is a honorific suffix). Halfway up the mountain, they built a temple sacred to Fudo Myo-o in association with the stone statue Priest Roben had found.*** In other words, it had a Shinto shrine on the top, and Buddhist (Shingon) temple in the mid-slope of the mountain. Like other temple/shrine complex, however, Buddhist elements were more pronounced in this complex as well, and it was Buddhist priests, if anything, who controlled the institution. In the Shrine’s case, Shingon Esoteric Buddhism prevailed under the name of Afurisan Oyamadera, which, is literally a “rainfall-inducing-great-mountain” temple and Sekison was called Sekison Daigongen. (Gongen denotes manifestation of Buddha).

Oyama Afuri Jinja Shrine and Roben

***Priest Roben, who was de facto founding priest of Todaiji, came back to Kanagawa in 752 at the age of 48, shortly after the consecrating ceremony of the Great Buddha at Todaiji was over. First thing he did in Kanagawa was to climb Mt. Oyama, literally “a great mountain” and highly revered by the locals, where he found a stone statue of Fudo Myo-o, or Acala-vidyaraja in Skt. Interpreting it was a divine revelation, he made up his mind to found a temple (not a shrine) right on top of the mountain. He practiced asceticism in the mountain for three years. Getting the emperor’s approval, he finally built a temple and named it Afurisan Oyamadera. – Source: Oyama Afuri Jinja Shrine

The Wikipedia on Oyama Afuri Jinja Shrine and Roben:

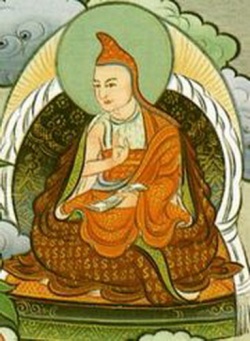

Roben In 740, the twelfth year of the Tenpyō era, an eminent Korean monk of the Silla kingdom (57 BC – 935 AD) named Simsang (審祥), known as Shinjō in Japan, was invited by Rōben to Japan to help establish a new sect based on the Huayan school of thought. This led to the foundation of the Kegon school of Buddhism with permission from Emperor Shōmu. Rōben subsequently became the second patriarch of the Kegon school. Rōben first studied Hossō Buddhism under the monk Gien (義淵) (d. 728). Gien and his disciples Rōben and Gyōgi are considered to have created the foundation of Japanese Buddhism at the beginning of the Nara period. In 733, the fifth year of the Tenpyō era, Rōben oversaw expansion and construction of Kinshō-ji (金鐘寺) and the massive bronze statue of Vairocana Buddha under the patronage of Emperor Shōmu (724 – 749). Kinshō-ji is now the Hokke-dō hall of Tōdai-ji.

The rain-maker’s sacred rain-stones*, parallels with cultural practices from other countries:

Stones are often supposed to possess the property of bringing on rain, provided they be dipped in water or sprinkled with it, or treated in some other appropriate manner. In a Samoan village a certain stone was carefully housed as the representative of the rainmaking god, and in time of drought his priests carried the stone in procession and dipped it in a stream.

Among the Ta-ta-thi tribe of New South Wales, the rain-maker breaks off a piece of quartz-crystal and spits it towards the sky; the rest of the crystal he wraps in emu feathers, soaks both crystal and feathers in water, and carefully hides them. In the Keramin tribe of New South Wales the wizard retires to the bed of a creek, drops water on a round flat stone, then covers up and conceals it. Among some tribes of North-western Australia the rain-maker repairs to a piece of ground which is set apart for the purpose of rain-making. There he builds a heap of stones or sand, places on the top of it his magic stone, and walks or dances round the pile chanting his incantations for hours, till sheer exhaustion obliges him to desist, when his place is taken by his assistant. Water is sprinkled on the stone and huge fires are kindled. No layman may approach the sacred spot while the mystic ceremony is being performed. When the Sulka of New Britain wish to procure rain they blacken stones with the ashes of certain fruits and set them out, along with certain other plants and buds, in the sun. Then a handful of twigs is dipped in water and weighted with stones, while a spell is chanted. After that rain should follow. In Manipur, on a lofty hill to the east of the capital, there is a stone which the popular imagination likens to an umbrella. When rain is wanted, the rajah fetches water from a spring below and sprinkles it on the stone. At Sagami in Japan there is a stone which draws down rain whenever water is poured on it.

… In New Caledonia when a wizard desires to make sunshine, he takes some plants and corals to the burial-ground, and fashions them into a bundle, adding two locks of hair cut from a living child of his family, also two teeth or an entire jawbone from the skeleton of an ancestor. He then climbs a mountain whose top catches the first rays of the morning sun.

Here he deposits three sorts of plants on a flat stone, places a branch of dry coral beside them, and hangs the bundle of charms over the stone. Next morning he returns to the spot and sets fire to the bundle at the moment when the sun rises from the sea. As the smoke curls up, he rubs the stone with the dry coral, invokes his ancestors and says: “Sun! I do this that you may be burning hot, and eat up all the clouds in the sky.” The same ceremony is repeated at sunset. The New Caledonians also make a drought by means of a discshaped stone with a hole in it. At the moment when the sun rises, the wizard holds the stone in his hand and passes a burning brand repeatedly into the hole, while he says: “I kindle the sun, in order that he may eat up the clouds and dry up our land, so that it may produce nothing.” The Banks Islanders make sunshine by means of a mock sun. They take a very round stone, called a vat loa or sunstone, wind red braid about it, and stick it with owls’ feathers to represent rays, singing the proper spell in a low voice. Then they hang it on some high tree, such as a banyan or a casuarina, in a sacred place…

— p. 75b James Frazer, The Golden Bough

The “Dark Rain Dragon” as recorded in the Nihongi

The ca. 720 CE Nihongi writes Kuraokami with kanji as 闇龗 “dark rain-dragon”. In the Nihongi version, Izanagi killed Kagutsuchi by cutting him into three pieces, each of which became a god: Kuraokami, Kurayamatsumi 闇山祇 “dark mountain respect”, and Kuramitsuha 闇罔象 “dark water-sprit”. This mitsuha罔象 is a variant of mōryō 魍魎 “demon; evil spirit” (written with the “ghost radical” 鬼). Kurayamatsumi is alternately written Takaokami 高靇 “high rain-dragon”. Visser (1913:136) says, “This name is explained by one of the commentators as “the dragon-god residing on the mountains”, in distinction from Kura-okami, “the dragon-god of the valleys”.

At length he drew the ten-span sword with which he was girt, and cut Kagu tsuchi into three pieces, each of which became changed into a God. Moreover, the blood which dripped from the edge of the sword became the multitudinous rocks which are in the bed of the Easy-River of Heaven. This God was the father of Futsu-nushi no Kami. Moreover, the blood which dripped from the hilt-ring of the sword spurted out and became deities, whose names were Mika no Haya-hi no Kami and next Hi no Haya-hi no Kami. This Mika no Haya-hi no Kami was the parent of ppTake-mika-suchi no Kami)].

Another version is: “ppMika no haya-hi no Mikoto[[, next ppHi no haya-hi no Mikoto, and next ppTake-mika-tsuchi no Kami. Moreover, the blood which dripped from the point of the sword spurted out and became deities, who were called ppIha-saku no Kami)], after him Ne-saku no Kami, and next Iha-tsutsu-wo no Mikoto. This Iha-saku no Kami was the father of Futsu-nushi no Kami.”

One account says: “Iha-tsutsu-wo no Mikoto, and next Iha-tsutsu-me no Mikoto. Moreover, the blood which dripped from the head of the sword spurted out and became deities, who were called Kura o Kami no Kami, next Kura-yamatsumi no Kami, and next Kura-midzu-ha no Kami. (tr. Aston 1896:23)

William George Aston (1896:24) footnotes translations for these kami names: Kuraokami “Dark-god”, Kurayamatsumi “Dark-mountain-body-god”, and Kuramitsuha “Dark-water-goddess”. De Visser (1913:136-7) says (Kuramitsuha could be translated “Dark-water-snake”, “Valley-water-snake”, or “Female-water-snake.”

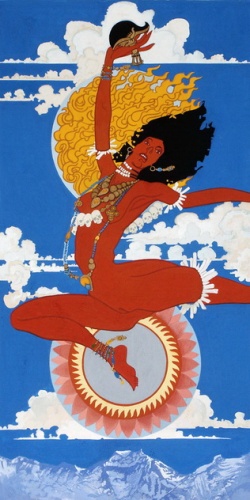

Kuraokami (闇龗), Okami (龗), or Okami no kami (淤加美神) is a legendary Japanese dragon and Shinto deity of rain and snow. In Japanese mythology, the sibling progenitors Izanagi and Izanami gave birth to the islands and gods of Japan. After Izanami died from burns during the childbirth of the fire deity Kagutsuchi, Izanagi was enraged and killed his son. Kagutsuchi’s blood or body, according to differing versions of the legend, created several other deities, including Kuraokami.

The name Kuraokami combines kura 闇 ”dark; darkness; closed” and okami 龗 ”dragon tutelary of water”. This uncommon kanji (o)kami or rei 龗, borrowed from the Chinese character ling 龗 ”rain-dragon; mysterious” (written with the “rain” radical 雨, 3 口 ”mouths”, and a phonetic of long 龍 ”dragon”) is a variant Chinese character for Japanese rei < Chinese ling 靈 ”rain-prayer; supernatural; spiritual” (with 2 巫 ”shamans” instead of a “dragon”). Compare this 33-stroke 龗 logograph with the simpler 24-stroke variant 靇 (“rain” and “dragon” without the “mouths”), read either rei < ling 靇 “rain prayer; supernatural” or ryō < long 靇 “sound of thunder”, when used for ryo < long 隆 reduplicated in ryōryō < longlong 隆隆 “rumble; boom”.

From the Wikipedia entry on the Suijin watergod, Okami and ~okami rain gods, and the Japanese rain-dragon, Kuraokama a.k.a. Takaokami:

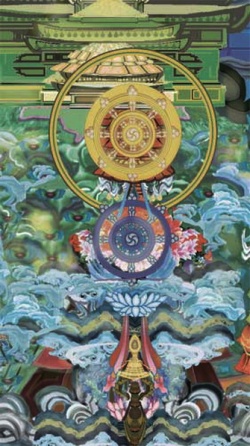

The diverse Japanese kami of water and rainfall, such as Suijin 水神 “water god” and Okami, are worshipped at Shinto shrines, especially during times of drought. For instance, Niukawakami Jinja 丹生川上神社 in Kawakami, Nara is a center of prayers for Kuraokami, Takaokami, and Mizuhanome 罔象女. There are over 2000 shrines that incorporate the ‘okami’ of the enshrined deity’s name into the shrine name (Takaokami-jinja Shrine, Okami-jinja Shrine, Kuraokami-jinja Shrine, etc.).

Okami associations with the snake dragon:

Marinus Willem de Visser (1913:136) cites the 713 CE Bungo Fudoki 豊後風土記 that okami is written 蛇龍 “snake dragon” in a context about legendary Emperor Keikō seeing an okami dragon in a well, and concludes, “This and later ideas about Kura-okami show that this divinity is a dragon or snake”.

Some other examples of shrines to Okami are:

Okami Jinja 龗神社 in Daitō, Osaka

Okami Jinja 於加美神社 in Minamiaizu, Fukushima

Okami Jinja 意加美神社 in Hirakata and Izumisano, Osaka

Kuraokami Jinja 闇龗神社 in Ichikai, Tochigi

Takaokami Jinja 高龗神社 on Mount Miwa

Takaokami Jinja 多加意加美神社 in Shōbara, Hiroshima

Kunitsu Okami Jinja 國津意加美神社 on Iki Island

In addition, the water-god Takaokami is worshipped at various shrines named Kibune Jinja 貴船神社, found in places such as Sakyō-ku, Kyoto and Manazuru, Kanagawa. See source readings below:

Smith, G. Elliot. 1919. The Evolution of the Dragon. Longmans, Green & Company. Pdf version

Visser, Marinus Willern de. 1913. The Dragon in China and Japan. J. Müller

Aston, William George, tr. 1896. Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. 2 vols. Kegan Paul.

Chamberlain, Basil H., tr. 1919. The Kojiki, Records of Ancient Matters.