Difference between revisions of "Bardo Teachings"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

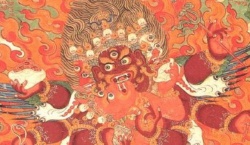

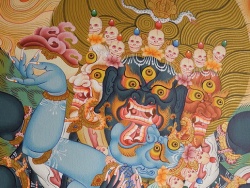

[[File:Zhi-Khro Bardo.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Zhi-Khro Bardo.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

[[Venerable]] [[Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche]] | [[Venerable]] [[Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche]] | ||

| Line 6: | Line 11: | ||

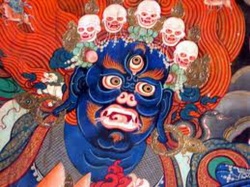

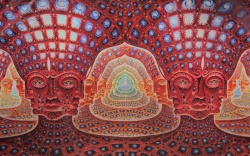

[[File:Wrat eity.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Wrat eity.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

Introduction | Introduction | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

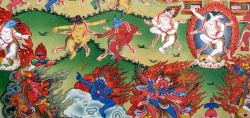

[[File:WFBardo-9.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:WFBardo-9.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | I am going to discuss the [[bardo]]. Although we often speak of [[six bardos]], here I’m only going to discuss four. These four [[bardos]] cover the whole of [[existence]], but when we use the [[word]] [[bardo]], which means ‘in-between,’ we are usually referring to the [[time]] between [[death]] and [[birth]]. Some [[people]] may think that {{Wiki|learning}} about what happens after we [[die]] while we are still alive is a waste of [[time]]. But it’s extremely important to know what will happen when we [[die]]. If, while still alive, we study what is going to happen when we [[die]], then we will be prepared to deal with the [[appearances]] that arise in the [[bardo]]. | + | I am going to discuss the [[bardo]]. Although we often speak of [[six bardos]], here I’m only going to discuss four. These four [[bardos]] cover the whole of [[existence]], but when we use the [[word]] [[bardo]], which means ‘in-between,’ we are usually referring to the [[time]] between [[death]] and [[birth]]. Some [[people]] may think that {{Wiki|learning}} about what happens after we [[die]] while we are still |

| + | |||

| + | alive is a waste of [[time]]. But it’s extremely important to know what will happen when we [[die]]. If, while still alive, we study what is going to happen when we [[die]], then we will be prepared to deal with the [[appearances]] that arise in the [[bardo]]. | ||

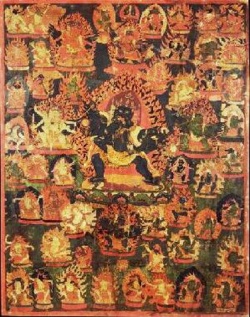

[[File:WFBardo-5.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:WFBardo-5.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

Other [[people]] may be so [[attached]] to [[life]] that they have not given the [[bardo]] any [[thought]]. They may even think they will not [[experience]] the [[bardo]]. Obviously, this is a big mistake. It’s very important to train for the [[bardo]] while still alive, because we can be 100% certain that we will [[experience]] it, and preparing for it will ensure that we will meet its challenge skilfully. | Other [[people]] may be so [[attached]] to [[life]] that they have not given the [[bardo]] any [[thought]]. They may even think they will not [[experience]] the [[bardo]]. Obviously, this is a big mistake. It’s very important to train for the [[bardo]] while still alive, because we can be 100% certain that we will [[experience]] it, and preparing for it will ensure that we will meet its challenge skilfully. | ||

[[File:WFBardo-4.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:WFBardo-4.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Yet other [[people]] may have the [[impression]] that they do not particularly need to train for the [[bardo]], that if they practice [[Dharma]] they will be fine. Or they might think that the [[bardo]] is something scary, something bad, and so they don’t want to think about it. But both these approaches are wrong. The [[appearances]] of the [[bardo]] are fleeting, so we need to train in them before they appear in order to utilize them. If we develop the capability to deal with them while alive, then we will [[recognize]] even the bad and scary things we encounter in that state as fleeting [[appearances]]. This will stop us from being afraid. If we train to [[recognize]] [[appearances]], we may even be able to attain the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] [[siddhi]] (‘[[accomplishment]]’) in the [[bardo]]. Even if we do not attain this [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] goal, we will at least be able to take a good [[birth]]. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | Yet other [[people]] may have the [[impression]] that they do not particularly need to train for the [[bardo]], that if they practice [[Dharma]] they will be fine. Or they might think that the [[bardo]] is something scary, something bad, and so they don’t want to think about it. But both these approaches are wrong. The [[appearances]] of the [[bardo]] are fleeting, so we need to train in them before they appear in order to utilize them. If we develop the capability to deal with them while alive, then we will [[recognize]] even the bad and scary things | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | we encounter in that [[state]] as fleeting [[appearances]]. This will stop us from being afraid. If we train to [[recognize]] [[appearances]], we may even be able to attain the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] [[siddhi]] (‘[[accomplishment]]’) in the [[bardo]]. Even if we do not attain this [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] goal, we will at least be able to take a good [[birth]]. | ||

[[File:WFBardo-11.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:WFBardo-11.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Lord]] [[Buddha]] and the great practitioners who appeared after him have given us instructions on how to deal with the [[bardo]]. They explained the [[appearances]] that will arise and the way we should apply ourselves when they do. Having these instructions means that when the [[time]] comes, we can follow them and by [[recognizing]] what is happening to us, we can ensure we have a good [[birth]] and not a bad one. If we don’t have this [[knowledge]] and haven’t put it into practice, we may become confused by the [[imagery]] we [[experience]] in the [[bardo]] and fall into a bad [[realm]], where we will [[experience]] a great deal of [[suffering]]. If we are familiar with what we are going to [[experience]], however, we will know how to steer ourselves towards a good [[birth]]. This is why it’s very important to listen to and reflect on these teachings. By doing this, we will remember them throughout our lifetimes and be prepared for [[death]]. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | [[Lord]] [[Buddha]] and the great practitioners who appeared after him have given us instructions on how to deal with the [[bardo]]. They explained the [[appearances]] that will arise and the way we should apply ourselves when they do. Having these instructions means that when the [[time]] comes, we can follow them and by [[recognizing]] what is happening to us, we can ensure we have a good [[birth]] and not a bad one. If we don’t have this [[knowledge]] and haven’t put it into practice, we may become confused by the [[imagery]] we [[experience]] in the | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[bardo]] and fall into a bad [[realm]], where we will [[experience]] a great deal of [[suffering]]. If we are familiar with what we are going to [[experience]], however, we will know how to steer ourselves towards a good [[birth]]. This is why it’s very important to listen to and reflect on these teachings. By doing this, we will remember them throughout our lifetimes and be prepared for [[death]]. | ||

[[File:WFBardo-10.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:WFBardo-10.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | When we teach [[people]] about the [[bardo]], it’s important to remember that not everyone will be 100% sure about the [[existence]] of {{Wiki|future}} [[lives]]. Some of you will be 100% sure and therefore understand the importance of studying these teachings. As one of these [[people]], you may think that these are the [[Buddha’s teachings]], which he taught in both the [[Sutras]] and again in the [[Tantras]] and which were taught by other [[masters]]. So you are absolutely certain of their validity. But it’s also possible that some of you are not 100% sure about this. You are not absolutely sure that there will be {{Wiki|future}} [[lives]] and a [[bardo]] between this [[life]] and the next. Still, even if you are one of these [[people]], it is still important to study the [[bardo]]. If there is any chance that there is a [[bardo]], then it is a good [[idea]] to prepare for it. It’s unlikely that anyone is 100% certain that there are no {{Wiki|future}} [[lives]]; this kind of certainty is hard to come by. If you could be 100% certain about the [[non-existence]] of {{Wiki|future}} [[lives]], you wouldn’t need to learn about the [[bardo]] or put the instructions into practice. But if you are not completely certain, if you think there is even a slim chance that there is a [[bardo]], it would be a good [[idea]] to develop some [[understanding]] of what is going to happen when you [[experience]] it. This way, if you are 100% certain that there is a [[bardo]], you will want to hear these teachings and put them into practice. And even if you aren’t 100% sure, you will still want to hear these teachings and put them into practice – just in case. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | When we teach [[people]] about the [[bardo]], it’s important to remember that not everyone will be 100% sure about the [[existence]] of {{Wiki|future}} [[lives]]. Some of you will be 100% sure and therefore understand the importance of studying these teachings. As one of these [[people]], you may think that these are the [[Buddha’s teachings]], which he [[taught]] in both the [[Sutras]] and again in the [[Tantras]] and which were [[taught]] by other [[masters]]. So you are absolutely certain of their validity. But it’s also possible that some of you are not 100% | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | sure about this. You are not absolutely sure that there will be {{Wiki|future}} [[lives]] and a [[bardo]] between this [[life]] and the next. Still, even if you are one of these [[people]], it is still important to study the [[bardo]]. If there is any chance that there is a [[bardo]], then it is a good [[idea]] to prepare for it. It’s unlikely that anyone is 100% certain that there are no {{Wiki|future}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[lives]]; this kind of {{Wiki|certainty}} is hard to come by. If you could be 100% certain about the [[non-existence]] of {{Wiki|future}} [[lives]], you wouldn’t need to learn about the [[bardo]] or put the instructions into practice. But if you are not completely certain, if you think there is even a slim chance that there is a [[bardo]], it would be a good [[idea]] to develop some [[understanding]] of what is going to | ||

| + | |||

| + | happen when you [[experience]] it. This way, if you are 100% certain that there is a [[bardo]], you will want to hear these teachings and put them into practice. And even if you aren’t 100% sure, you will still want to hear these teachings and put them into practice – just in case. | ||

[[File:Vajra Being.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Vajra Being.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

The Natural [[Bardo]] of this [[Life]] | The Natural [[Bardo]] of this [[Life]] | ||

[[File:Thumb TH31.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Thumb TH31.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

The first [[bardo]] we will discuss is the natural [[bardo of this life]]. What does this mean? It refers to the [[life]] that we are experiencing right now. This is not usually what we think of when we hear the [[word]] [[bardo]], is it? But it is in this [[life]] – between [[birth]] and [[death]] – that we can train for the [[bardo]] between [[lives]]. | The first [[bardo]] we will discuss is the natural [[bardo of this life]]. What does this mean? It refers to the [[life]] that we are experiencing right now. This is not usually what we think of when we hear the [[word]] [[bardo]], is it? But it is in this [[life]] – between [[birth]] and [[death]] – that we can train for the [[bardo]] between [[lives]]. | ||

[[File:The second bardo.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:The second bardo.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The [[bardo of this life]] begins the moment we are born. From the moment we are born, when we emerge from our mother’s [[womb]], we begin to [[experience]] all the confused [[appearances]] that constitute the [[bardo of this life]]. This [[bardo]], however, also grants us the opportunity to train for the next [[bardo]], and if we train according to the teachings, we will make it through the next [[bardo]] without any difficulties and perhaps even {{Wiki|liberate}} ourselves from [[suffering]]. If we put in the [[effort]] now, we will be rewarded by a lack of [[suffering]] in the next [[bardo]]. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | The [[bardo of this life]] begins the [[moment]] we are born. From the [[moment]] we are born, when we emerge from our mother’s [[womb]], we begin to [[experience]] all the confused [[appearances]] that constitute the [[bardo of this life]]. This [[bardo]], however, also grants us the opportunity to train for the next [[bardo]], and if we train according to the teachings, we will make it through the next [[bardo]] without | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | any difficulties and perhaps even {{Wiki|liberate}} ourselves from [[suffering]]. If we put in the [[effort]] now, we will be rewarded by a lack of [[suffering]] in the next [[bardo]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[File:T107 97.071.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:T107 97.071.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | We can do this in one of [[three ways]], depending on what sort of [[person]] we are. It’s said that there are three types of [[people]]: those who are {{Wiki|excellent}}, those who are {{Wiki|superior}}, and those who are ordinary. {{Wiki|Excellent}} [[people]] don’t need any particular instructions on the [[bardo]]; they are already great [[meditators]] and have great realizations and [[understanding]], i.e., they have [[realized]] the [[deity]]. These qualities mean that they do not need to be particularly instructed as to what to do in the [[bardo]]. But [[ordinary people]] are not like this; [[ordinary people]] even lose themselves in the course of daily [[life]]. They are plagued by [[ignorance]], so they are very [[attached]] to the [[appearances]] of this [[life]]. This [[attachment]], in turn, creates other [[negative emotions]] and more confused [[appearances]]. [[Ordinary people]] like us hang on to [[ideas]] like “me,” “you,” and “other.” We hang on to [[ideas]] about the [[self]]. We hang on to what are called “the [[eight worldly concerns]]” that keep us from the [[path]]. They are: [[attachment]] to gain, to [[pleasure]], to praise, to [[fame]], and [[aversion]] to loss, to [[pain]], to blame, and to a bad reputation. Caught up by our [[grasping]] to these [[ideas]], a year will pass by, then two, then three, then four. Before we know it, our [[life]] has passed by in a cycle of {{Wiki|confusion}} and [[grasping]]. | + | We can do this in one of [[three ways]], depending on what sort of [[person]] we are. It’s said that there are three types of [[people]]: those who are {{Wiki|excellent}}, those who are {{Wiki|superior}}, and those who are ordinary. {{Wiki|Excellent}} [[people]] don’t need any |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | particular instructions on the [[bardo]]; they are already great [[meditators]] and have great realizations and [[understanding]], i.e., they have [[realized]] the [[deity]]. These qualities mean that they do not need to be particularly instructed as to what to do in the [[bardo]]. But [[ordinary people]] are not like this; [[ordinary people]] even lose themselves in the course of daily [[life]]. They are plagued by | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[ignorance]], so they are very [[attached]] to the [[appearances]] of this [[life]]. This [[attachment]], in turn, creates other [[negative emotions]] and more confused [[appearances]]. [[Ordinary people]] like us hang on to [[ideas]] like “me,” “you,” and “other.” We hang on to [[ideas]] about the [[self]]. We hang on to what are called “the [[eight worldly concerns]]” that keep us from the [[path]]. They are: | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[attachment]] to gain, to [[pleasure]], to praise, to [[fame]], and [[aversion]] to loss, to [[pain]], to blame, and to a bad reputation. Caught up by our [[grasping]] to these [[ideas]], a year will pass by, then two, then three, then four. Before we know it, our [[life]] has passed by in a cycle of {{Wiki|confusion}} and [[grasping]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[File:Stages of the Bardo.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Stages of the Bardo.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | This way, to train ourselves during the natural [[bardo of this life]] is to follow [[Lord]] [[Buddha’s]] instructions. He explained how to do this in both [[Sutras]] and [[Tantras]], and great [[teachers]] and practitioners have written commentaries on these instructions through the ages. To train ourselves well, we need to listen to these instructions and [[contemplate]] them so that we fully understand their meaning. Usually, this means going over and over them; studying and reflecting on the [[Sutras]] and [[Tantras]] and all the oral instructions. The purpose of doing this is not merely to become learned, praised, or famous. Rather, through this process of listening and contemplating, we allow our [[mind]] to gradually [[rest]] and settle into its [[natural state]]. Yet, even this is not enough. It isn’t enough to just listen to and reflect these teachings – we need to put them into practice. As the great practitioners of the {{Wiki|past}} showed us, we need to abandon all the misdeeds of our [[body]], [[speech]], and [[mind]]. We need to stop doing anything that will create problems for us. What is more, we need to start doing [[good deeds]] - {{Wiki|physically}}, verbally, and [[mentally]]. By refraining from misdeeds and engaging in [[good deeds]], we will be putting these instructions into practice. Not only will we have developed [[knowledge]] from listening to and contemplating them, but we will also know how these instructions work practically. [[Ordinary people]], [[people]] like us, need to put into practice instructions like those of [[Shantideva’s]] “The Way of the [[Bodhisattva]].” Here it is recommended that we approach everything with [[mindfulness]], [[awareness]], and [[carefulness]]. If we put this advice into practice, our days will not be lost in a chorus of [[negative emotions]] and [[thoughts]]. | + | This way, to train ourselves during the natural [[bardo of this life]] is to follow [[Lord]] [[Buddha’s]] instructions. He explained how to do this in both [[Sutras]] and [[Tantras]], and great [[teachers]] and practitioners have written commentaries on these instructions through |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | the ages. To train ourselves well, we need to listen to these instructions and [[contemplate]] them so that we fully understand their meaning. Usually, this means going over and over them; studying and {{Wiki|reflecting}} on the [[Sutras]] and [[Tantras]] and all the [[oral instructions]]. The {{Wiki|purpose}} of doing this is not merely to become learned, praised, or famous. Rather, through this process of listening and | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[contemplating]], we allow our [[mind]] to gradually [[rest]] and settle into its [[natural state]]. Yet, even this is not enough. It isn’t enough to just listen to and reflect these teachings – we need to put them into practice. As the great practitioners of the {{Wiki|past}} showed us, we need to abandon all the [[misdeeds]] of our [[body]], [[speech]], and [[mind]]. We need to stop doing anything that will create problems for us. What is more, we need to start doing [[good deeds]] - {{Wiki|physically}}, verbally, and [[mentally]]. By refraining from | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[misdeeds]] and engaging in [[good deeds]], we will be putting these instructions into practice. Not only will we have developed [[knowledge]] from listening to and [[contemplating]] them, but we will also know how these instructions work practically. [[Ordinary people]], [[people]] like us, need to put into practice instructions like those of [[Shantideva’s]] “The Way of the [[Bodhisattva]].” Here it is recommended that we | ||

| + | |||

| + | approach everything with [[mindfulness]], [[awareness]], and [[carefulness]]. If we put this advice into practice, our days will not be lost in a chorus of [[negative emotions]] and [[thoughts]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[File:Shitro5 eities.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Shitro5 eities.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | From the {{Wiki|perspective}} of [[Vajrayana]], putting [[Dharma]] into practice means first requesting an [[empowerment]]. In this [[empowerment]], our potential will develop, we are inspired, we attain a {{Wiki|degree}} of certainty, a {{Wiki|degree}} of [[courage]] and strength that enables us to put secret [[Mantrayana]] into practice. But this [[empowerment]] by itself is not enough. We also need [[vajra]] instructions from a qualified [[Vajrayana]] [[master]]. These instructions give us the detailed know-how to engage in [[Vajrayana]] [[meditations]]. We request to be instructed, listen, and reflect on the meaning of what we have been told. Then we put the instructions into practice as well as we can. We need to try and follow the instructions 100% of the [[time]]. Even if this isn’t something we may be able to do as beginners, we need to try. This means that during the day we should keep reminding ourselves, “What is it that I need to be doing? What [[habits]] should I be forming? What do I need to give up?” This way we will stay focused. We should also try to maintain this [[mindfulness]] at night, even while asleep and dreaming. Just as we can get lost in the [[appearances]] of waking [[life]], we can also get lost in the [[imagery]] of our [[dreams]] and let all sorts of [[negative emotions]] arise. Even when we are dreaming, we are still {{Wiki|aware}} of having [[good and bad]] [[thoughts]], so we need to keep focused on developing good ones. If we keep working at it, we will be able to stay {{Wiki|aware}} and incorporate the instructions 100% of the [[time]]. To do this, we need to keep working at it and make sure we don’t get distracted or lazy. | + | From the {{Wiki|perspective}} of [[Vajrayana]], putting [[Dharma]] into practice means first requesting an [[empowerment]]. In this [[empowerment]], our potential will develop, we are inspired, we attain a {{Wiki|degree}} of {{Wiki|certainty}}, a {{Wiki|degree}} of [[courage]] and |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | strength that enables us to put secret [[Mantrayana]] into practice. But this [[empowerment]] by itself is not enough. We also need [[vajra]] instructions from a qualified [[Vajrayana]] [[master]]. These instructions give us the detailed know-how to engage in [[Vajrayana]] [[meditations]]. We request to be instructed, listen, and reflect on the meaning of what we have been told. Then we put the instructions into | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | practice as well as we can. We need to try and follow the instructions 100% of the [[time]]. Even if this isn’t something we may be able to do as beginners, we need to try. This means that during the day we should keep reminding ourselves, “What is it that I need to be doing? What [[habits]] should I be forming? What do I need to give up?” This way we will stay focused. We should also try to maintain this [[mindfulness]] at night, even while asleep and [[Wikipedia:Dream|dreaming]]. Just as we can get lost in the [[appearances]] of waking [[life]], we can also get | ||

| + | |||

| + | lost in the [[imagery]] of our [[dreams]] and let all sorts of [[negative emotions]] arise. Even when we are [[Wikipedia:Dream|dreaming]], we are still {{Wiki|aware}} of having [[good and bad]] [[thoughts]], so we need to keep focused on developing good ones. If we keep working at it, we will be able to stay {{Wiki|aware}} and incorporate the instructions 100% of the [[time]]. To do this, we need to keep working at it and make sure we don’t get distracted or lazy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[File:Shithro557.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Shithro557.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | There are other ways we can practice. We can do the common and uncommon [[preparatory practices]], the [[Ngöndro]], or we could follow the instructions of “The [[Seven Points of Mind Training]].” Actually, this last set of teachings also contains a really helpful hint regarding these practices. It says, “Of the two witnesses, hold the [[principle]] one.” What this means is that there are two witnesses to our [[Dharma]] practice, ourself and other [[people]]. But if we really want to know if we have stopped doing things that will harm ourselves and others and started doing [[good deeds]], then we have to rely on our own [[insight]]. Other [[people]] cannot see what is going on in our [[mind]]. They can’t really tell what our motives are, whether we are [[abandoning]] [[negative emotions]] or not. They cannot, but we can. We can check ourselves, examine our [[mind]], and see what is going on. Are we getting lost in our [[negative emotions]]? Are we doing [[good deeds]]? Are we [[meditating]]? Are we doing the practices that we need to do? We practice the [[Dharma]] to [[benefit]] ourselves and to bring [[happiness]] to others, not so that someone else will think we are good. We have to rely on ourself as a {{Wiki|witness}} and observe what is happening in our own [[mind]]. | + | There are other ways we can practice. We can do the common and uncommon [[preparatory practices]], the [[Ngöndro]], or we could follow the instructions of “The [[Seven Points of Mind Training]].” Actually, this last set of teachings also contains a really helpful hint regarding these practices. It says, “Of the two witnesses, hold the [[principle]] one.” What this means is that there are two witnesses to our |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Dharma]] practice, ourself and other [[people]]. But if we really want to know if we have stopped doing things that will harm ourselves and others and started doing [[good deeds]], then we have to rely on our [[own]] [[insight]]. Other [[people]] cannot see what is going on in our [[mind]]. They can’t really tell what our motives are, whether we are [[abandoning]] [[negative emotions]] or not. They cannot, but we can. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | We can check ourselves, examine our [[mind]], and see what is going on. Are we getting lost in our [[negative emotions]]? Are we doing [[good deeds]]? Are we [[meditating]]? Are we doing the practices that we need to do? We practice the [[Dharma]] to [[benefit]] ourselves and to bring [[happiness]] to others, not so that someone else will think we are good. We have to rely on ourself as a {{Wiki|witness}} and observe what is happening in our [[own]] [[mind]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[File:SH14y.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:SH14y.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | It will make us very [[happy]] in a few ways if we do these practices and incorporate them in our [[life]]. For example, if we can do these [[meditation]] practices 100% of the [[time]], we will [[experience]] great [[joy]]. Even if we can’t, we can still [[feel]] good about trying our best, are practicing [[mindfulness]], and are being attentive and careful. On the other hand, we might find ourselves caught up in events and [[experiences]] of this [[life]]. We may wake up most mornings focusing our [[attention]] on our immediate needs and ignore the [[Dharma]]. We may lose ourselves in our confused [[experiences]] and [[negative emotions]], but at some point, we may think, “I need to integrate the [[Dharma]]. I need to think about what I am doing. I need to develop [[pure]] {{Wiki|intentions}} and generate [[loving kindness]] and [[compassion]].” Having these [[thoughts]] occasionally is also something to [[feel]] really [[happy]] about. | + | It will make us very [[happy]] in a few ways if we do these practices and incorporate them in our [[life]]. For example, if we can do these [[meditation]] practices 100% of the [[time]], we will [[experience]] great [[joy]]. Even if we can’t, we can still [[feel]] good about |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | trying our best, are practicing [[mindfulness]], and are being attentive and careful. On the other hand, we might find ourselves caught up in events and [[experiences]] of this [[life]]. We may wake up most mornings focusing our [[attention]] on our immediate needs and ignore the [[Dharma]]. We may lose ourselves in our confused [[experiences]] and [[negative emotions]], but at some point, we may think, “I need to | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | integrate the [[Dharma]]. I need to think about what I am doing. I need to develop [[pure]] {{Wiki|intentions}} and generate [[loving kindness]] and [[compassion]].” Having these [[thoughts]] occasionally is also something to [[feel]] really [[happy]] about. | ||

[[File:SH-20.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:SH-20.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Another main technique that the [[Buddha]] taught is to [[meditate]] on [[impermanence]] and [[death]]. It may seem at first glance that there is no way this will make us [[happy]]. We may ask, “How will [[thinking]] about [[death]] make me [[happy]]?” Well, in many ways it won’t, because [[thinking]] about [[impermanence]] and [[death]] is depressing. But it’s not without purpose. [[Thinking]] about this [[unhappy]] topic will lead us to an even [[greater]] [[happiness]]. We don’t think about dying and [[death]] so that we are [[unhappy]], but we do this to develop a [[greater]] [[understanding]] of what will engender [[greater]] [[happiness]]. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | Another main technique that the [[Buddha]] [[taught]] is to [[meditate]] on [[impermanence]] and [[death]]. It may seem at first glance that there is no way this will make us [[happy]]. We may ask, “How will [[thinking]] about [[death]] make me [[happy]]?” Well, in many ways it won’t, because [[thinking]] about [[impermanence]] and [[death]] is depressing. But it’s not without {{Wiki|purpose}}. [[Thinking]] about this | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[unhappy]] topic will lead us to an even [[greater]] [[happiness]]. We don’t think about dying and [[death]] so that we are [[unhappy]], but we do this to develop a [[greater]] [[understanding]] of what will engender [[greater]] [[happiness]]. | ||

[[File:Refuge Bardo B.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Refuge Bardo B.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

There are [[three ways]] that [[meditating]] on [[impermanence]] can make us [[happy]]. To start with, it’s the [[condition]] that directs us towards the [[Dharma]]. If we are someone who has not entered the gate of the [[Dharma]], don’t [[meditate]], or {{Wiki|worry}} about doing the right thing and not doing the wrong thing, then the [[thought]] of [[impermanence]] may get us started. Even if we have started on the [[path]], [[meditating]] [[impermanence]] can help keep us on track. If we lack [[diligence]], become lazy, or lose our way, [[meditating]] on [[impermanence]] spurs us on. Remembering that things are [[impermanent]] and we are going to [[die]] gives us impetus to act. So it can help in the beginning and in the middle. But how will it help in the end? Even when we [[experience]] the results of our [[meditation]], the [[thought]] of [[impermanence]] is still beneficial. In the end, we will be able to look back and see how helpful it was. Then we will understand that the [[sadness]] and {{Wiki|depression}} we felt when we started to [[meditate]] on [[impermanence]] were {{Wiki|temporary}} and spurred us on to [[experience]] true [[happiness]]. | There are [[three ways]] that [[meditating]] on [[impermanence]] can make us [[happy]]. To start with, it’s the [[condition]] that directs us towards the [[Dharma]]. If we are someone who has not entered the gate of the [[Dharma]], don’t [[meditate]], or {{Wiki|worry}} about doing the right thing and not doing the wrong thing, then the [[thought]] of [[impermanence]] may get us started. Even if we have started on the [[path]], [[meditating]] [[impermanence]] can help keep us on track. If we lack [[diligence]], become lazy, or lose our way, [[meditating]] on [[impermanence]] spurs us on. Remembering that things are [[impermanent]] and we are going to [[die]] gives us impetus to act. So it can help in the beginning and in the middle. But how will it help in the end? Even when we [[experience]] the results of our [[meditation]], the [[thought]] of [[impermanence]] is still beneficial. In the end, we will be able to look back and see how helpful it was. Then we will understand that the [[sadness]] and {{Wiki|depression}} we felt when we started to [[meditate]] on [[impermanence]] were {{Wiki|temporary}} and spurred us on to [[experience]] true [[happiness]]. | ||

[[File:Pos-kltrowo.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Pos-kltrowo.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| Line 41: | Line 140: | ||

If we use our waking [[time]] to practice for the [[bardo]] and try to do [[good deeds]], then when we [[experience]] [[impermanence]] and [[death]], we will be prepared. It we practice now, if we reflect on what the instructions on the [[bardo]] mean, we will be prepared when [[death]] and the [[bardo]] happen to us. What is more, one of the instructions associated with preparing for the [[bardo]] is to get rid of our [[negative emotions]] in our daily [[life]]. Then gradually these [[afflictions]] will {{Wiki|decrease}} and we will naturally tend towards [[goodness]]. It’s very important to train ourselves in this way and become [[mindful]] and careful of what we are doing. | If we use our waking [[time]] to practice for the [[bardo]] and try to do [[good deeds]], then when we [[experience]] [[impermanence]] and [[death]], we will be prepared. It we practice now, if we reflect on what the instructions on the [[bardo]] mean, we will be prepared when [[death]] and the [[bardo]] happen to us. What is more, one of the instructions associated with preparing for the [[bardo]] is to get rid of our [[negative emotions]] in our daily [[life]]. Then gradually these [[afflictions]] will {{Wiki|decrease}} and we will naturally tend towards [[goodness]]. It’s very important to train ourselves in this way and become [[mindful]] and careful of what we are doing. | ||

[[File:Peaceful guhyagarbha.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Peaceful guhyagarbha.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Again, I should {{Wiki|emphasize}} that it’s also important to use the [[time]] while we are [[sleeping]] effectively, especially our [[dreams]]. We should try to [[dream]] about doing [[good deeds]]. We should also try and stop ourselves from being overwhelmed by negative [[states of mind]] in our [[dreams]]. When we go to [[sleep]], we should think, “Tonight I’m going to practice [[virtue]] in my [[dreams]].” Now, this wish may not result in us having positive [[dreams]] the first [[time]] we formulate it. It probably won’t even work the second [[time]] we try, but gradually by articulating this wish, we are planting positive [[seeds]] that will ripen in our [[dreams]]. Focusing on our [[dreams]] in this way also helps us maintain [[mindfulness]] and [[carefulness]] in them and therefore [[seals]] us against [[negative emotions]] that may arise while we [[dream]]. By developing positive [[mental states]] in this way and forestalling negative states through [[mindfulness]] and [[awareness]], we will gradually gain control over the [[appearances]] in our [[dreams]]. Developing this control will also enable us to see the [[illusory]] [[appearances]] of the [[bardo]] for what they are. In this way, training ourselves night and day in this [[life]] will help us attain a good [[birth]] in our {{Wiki|future}} [[lives]]. | + | Again, I should {{Wiki|emphasize}} that it’s also important to use the [[time]] while we are [[sleeping]] effectively, especially our [[dreams]]. We should try to [[dream]] about doing [[good deeds]]. We should also try and stop ourselves from being overwhelmed by negative [[states of mind]] in our [[dreams]]. When we go to [[sleep]], we should think, “Tonight I’m going to practice [[virtue]] in my [[dreams]].” Now, this wish may not result in us having positive [[dreams]] the first [[time]] we formulate it. It probably won’t even work the second [[time]] we try, but gradually by articulating this wish, we are planting positive [[seeds]] that will ripen in our [[dreams]]. Focusing on our [[dreams]] in this way also helps us maintain [[mindfulness]] and [[carefulness]] in them and therefore [[seals]] us against [[negative emotions]] that may arise while we [[dream]]. By developing positive [[mental states]] in this way and forestalling negative states through [[mindfulness]] and [[awareness]], we will gradually gain control over the [[appearances]] in our [[dreams]]. Developing this control will also enable us to see the [[illusory]] [[appearances]] of the [[bardo]] for what they are. In this way, {{Wiki|training}} ourselves night and day in this [[life]] will help us attain a good [[birth]] in our {{Wiki|future}} [[lives]]. |

[[File:Peac ities.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Peac ities.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | We may also take [[meditations]] from the [[development stage]] of [[Tantras]] and use them to prepare ourselves for the [[bardo]]. We may wish, for example, to [[visualize]] [[Noble]] [[Chenrezig]] or [[Lord]] [[Buddha]] in the sky in front of us. Based on this presence, we may then [[visualize]] ourselves making [[offerings]] to them or making aspirations to become like them. This type of [[visualization]] helps us appreciate them, to develop a strong bond with them, and to create [[merit]]. Alternately, we may [[visualize]] ourselves as one of the [[deities]] and gradually replace the [[Wikipedia:Habit (psychology)|habit]] of the impure [[appearances]] of our ordinary [[life]] with the [[pure]] [[appearances]] of the [[deity]]. | + | We may also take [[meditations]] from the [[development stage]] of [[Tantras]] and use them to prepare ourselves for the [[bardo]]. We may wish, for example, to [[visualize]] [[Noble]] [[Chenrezig]] or [[Lord]] [[Buddha]] in the sky in front of us. Based on this presence, we may then [[visualize]] ourselves making [[offerings]] to them or making [[aspirations]] to become like them. This type of [[visualization]] helps us appreciate them, to develop a strong bond with them, and to create [[merit]]. Alternately, we may [[visualize]] ourselves as one of the [[deities]] and gradually replace the [[Wikipedia:Habit (psychology)|habit]] of the impure [[appearances]] of our ordinary [[life]] with the [[pure]] [[appearances]] of the [[deity]]. |

[[File:Pea hive.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Pea hive.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Whether we are [[visualizing]] the [[meditation]] [[deities]] in front of us or ourselves as them, the [[clarity]] of our [[visualization]] may be greatly affected by the [[conditions]] of the channels and [[winds]] inside our [[body]]. For some, the state of their [[winds]] and channels leads to a very clear [[visualization]], for others the image they are trying to focus on isn’t very clear. The [[clarity]] of the image, however, isn’t that important. It’s important that we make a [[Wikipedia:Habit (psychology)|habit]] of remembering the [[deity]]. If the image itself is not very clear, we can focus on the [[deity’s]] [[body]]; we can think about its {{Wiki|color}}, its jewellery, ornaments, and implements. | + | Whether we are [[visualizing]] the [[meditation]] [[deities]] in front of us or ourselves as them, the [[clarity]] of our [[visualization]] may be greatly affected by the [[conditions]] of the [[channels]] and [[winds]] inside our [[body]]. For some, the [[state]] of their [[winds]] and [[channels]] leads to a very clear [[visualization]], for others the image they are trying to focus on isn’t very clear. The [[clarity]] of the image, however, isn’t that important. It’s important that we make a [[Wikipedia:Habit (psychology)|habit]] of remembering the [[deity]]. If the image itself is not very clear, we can focus on the [[deity’s]] [[body]]; we can think about its {{Wiki|color}}, its jewellery, ornaments, and implements. |

[[File:PBardo-9.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:PBardo-9.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

So, this is the first of the four [[bardos]], the natural [[bardo of this life]]. It’s important in this [[bardo]] to try to be [[mindful]], attentive, and careful. If you have any [[doubts]], are confused, and have questions, please ask. | So, this is the first of the four [[bardos]], the natural [[bardo of this life]]. It’s important in this [[bardo]] to try to be [[mindful]], attentive, and careful. If you have any [[doubts]], are confused, and have questions, please ask. | ||

| Line 51: | Line 150: | ||

Questions & Answers | Questions & Answers | ||

[[File:PBardo-10.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:PBardo-10.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Question: “[[Rinpoche]], is the [[teacher]] in the [[bardo]] with the student or is the student on his or her own?” [[Translator]]: “Are you talking about the [[bardo]] between [[lives]]?” Student: “Yes.” [[Thrangu Rinpoche]]: Everyone has to go through the [[bardo]], whether they are a [[Lama]] or a student. But there’s no certainty that we’ll go through the [[bardo]] at the same [[time]]. If we yearn for this to happen, however, and have much [[faith]] and [[devotion]], it’s possible to encounter the [[appearance]] of our [[Guru]] in the [[bardo]]. | + | Question: “[[Rinpoche]], is the [[teacher]] in the [[bardo]] with the [[student]] or is the [[student]] on his or her [[own]]?” [[Translator]]: “Are you talking about the [[bardo]] between [[lives]]?” [[Student]]: “Yes.” [[Thrangu Rinpoche]]: Everyone has to go through the [[bardo]], whether they are a [[Lama]] or a [[student]]. But there’s no {{Wiki|certainty}} that we’ll go through the [[bardo]] at the same [[time]]. If we yearn for this to happen, however, and have much [[faith]] and [[devotion]], it’s possible to encounter the [[appearance]] of our [[Guru]] in the [[bardo]]. |

[[File:Net-of-being.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Net-of-being.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Next question: “[[Rinpoche]], I have a question with [[respect]] to training in [[mindfulness]]. I just wanted to ask how to make sure we don’t accumulate [[negative emotions]] by judging [[people]] while we are trying to do this. I’ve heard that it’s good to develop discriminating [[awareness]], but it seems to me that a side-product of this is that it’s easy to become judgemental. Could [[Rinpoche]] give us some advice of how to [[transform]] our [[judgements]] of others?” TR: In the teachings on [[mindfulness]] and attentiveness, the focus is not really on anything external, which includes other [[people]]. If we look at the analogies by which it is taught, we can see this quite clearly. In “The Way of the [[Bodhisattva]],” [[Shantideva]] tells us that if the ground is covered with stones and thorns, we have two choices, to cover the entire [[world]] with leather or to wear shoes. In the same way, if we can {{Wiki|protect}} our own [[mind]] through [[mindfulness]], [[awareness]], and [[carefulness]], we prevent harm from [[arising]]. It doesn’t say to {{Wiki|protect}} other people’s [[minds]]. | + | Next question: “[[Rinpoche]], I have a question with [[respect]] to {{Wiki|training}} in [[mindfulness]]. I just wanted to ask how to make sure we don’t [[accumulate]] [[negative emotions]] by judging [[people]] while we are trying to do this. I’ve heard that it’s good to develop discriminating [[awareness]], but it seems to me that a side-product of this is that it’s easy to become judgemental. Could [[Rinpoche]] give us some advice of how to [[transform]] our [[judgements]] of others?” TR: In the teachings on [[mindfulness]] and attentiveness, the focus is not really on anything external, which includes other [[people]]. If we look at the analogies by which it is [[taught]], we can see this quite clearly. In “The Way of the [[Bodhisattva]],” [[Shantideva]] tells us that if the ground is covered with stones and thorns, we have two choices, to cover the entire [[world]] with leather or to wear shoes. In the same way, if we can {{Wiki|protect}} our [[own]] [[mind]] through [[mindfulness]], [[awareness]], and [[carefulness]], we prevent harm from [[arising]]. It doesn’t say to {{Wiki|protect}} other people’s [[minds]]. |

Next question: “[[Rinpoche]], you talked about the need to train in [[mindfulness]] during the daytime and our [[dreams]], but sometimes we wake in the morning and realize that we weren’t [[mindful]] in our [[dreams]]. What should we do about this?” TR: Training in [[dreams]] is a [[gradual]] process and sometimes we will have bad [[dreams]]. But if we develop the [[intention]] to have good [[dreams]], gradually they will start happening. What we need to do is maintain our positive {{Wiki|intentions}} and to keep working at it. | Next question: “[[Rinpoche]], you talked about the need to train in [[mindfulness]] during the daytime and our [[dreams]], but sometimes we wake in the morning and realize that we weren’t [[mindful]] in our [[dreams]]. What should we do about this?” TR: Training in [[dreams]] is a [[gradual]] process and sometimes we will have bad [[dreams]]. But if we develop the [[intention]] to have good [[dreams]], gradually they will start happening. What we need to do is maintain our positive {{Wiki|intentions}} and to keep working at it. | ||

| − | Q.: “I’m one of those [[people]] that don’t remember their [[dreams]]. Do you know any technique to help me remember them?” TR: This could mean that either you don’t remember your [[dreams]] or you aren’t dreaming. In either case, the best way to deal with this is to [[relax]] a little bit, i.e., wear your [[mindfulness]] and attentiveness a little more loosely. | + | Q.: “I’m one of those [[people]] that don’t remember their [[dreams]]. Do you know any technique to help me remember them?” TR: This could mean that either you don’t remember your [[dreams]] or you aren’t [[Wikipedia:Dream|dreaming]]. In either case, the best way to deal with this is to [[relax]] a little bit, i.e., wear your [[mindfulness]] and attentiveness a little more loosely. |

Q.: “What is the meaning of [[mindfulness]]?” TR: It means not {{Wiki|forgetting}} [[goodness]], i.e., constantly remembering what it is we should be doing and what we should not be doing. It means to remember as opposed to {{Wiki|forgetting}}. Those with {{Wiki|excellent}} [[mindfulness]] always remember what they should be doing and what they shouldn’t be doing. Other [[people]] may be a little less [[mindful]] and only remember every hour or so. Other [[people]] may only have a [[thought]] like, “Be good and [[compassionate]]. Try not to do anything harmful” once a day. Even if we only remember these things once a day, it’s still [[mindfulness]]. What we need to do is develop our [[mindfulness]]. We need to start reminding ourselves again and again what we should be doing and what is best to stop doing. | Q.: “What is the meaning of [[mindfulness]]?” TR: It means not {{Wiki|forgetting}} [[goodness]], i.e., constantly remembering what it is we should be doing and what we should not be doing. It means to remember as opposed to {{Wiki|forgetting}}. Those with {{Wiki|excellent}} [[mindfulness]] always remember what they should be doing and what they shouldn’t be doing. Other [[people]] may be a little less [[mindful]] and only remember every hour or so. Other [[people]] may only have a [[thought]] like, “Be good and [[compassionate]]. Try not to do anything harmful” once a day. Even if we only remember these things once a day, it’s still [[mindfulness]]. What we need to do is develop our [[mindfulness]]. We need to start reminding ourselves again and again what we should be doing and what is best to stop doing. | ||

| − | Q.: “In our {{Wiki|western}} {{Wiki|societies}}, many [[people]] are killed in car crashes or plane accidents and many of these [[people]] may not be [[Buddhists]]. Is there a particular method that we can use to help them?” TR: In this situation, the best thing to do is pray, making positive aspirations on their behalf. Will this actually help in the short term? The answer is, no. But it is planting the seed of freedom and [[liberation]]. It may not help straightaway, but in the {{Wiki|future}} this practice will ripen into great results. | + | Q.: “In our {{Wiki|western}} {{Wiki|societies}}, many [[people]] are killed in car crashes or plane accidents and many of these [[people]] may not be [[Buddhists]]. Is there a particular method that we can use to help them?” TR: In this situation, the best thing to do is pray, making positive [[aspirations]] on their behalf. Will this actually help in the short term? The answer is, no. But it is planting the seed of freedom and [[liberation]]. It may not help straightaway, but in the {{Wiki|future}} this practice will ripen into great results. |

| − | Q.: “There is a [[tradition]] of reading ‘The [[Book]] of [[Liberation]] through Hearing in the [[Bardo]]’ to [[people]] who have [[died]]. I wonder how helpful this is?” TR: When someone has [[died]] and is in the [[bardo]], they have miraculous [[powers]], e.g., they are {{Wiki|clairvoyant}}. This means that if we read this [[book]] to them, they will understand and [[experience]] it. This [[book]] is a [[pointing-out instruction]] for those who are in the [[bardo]] between [[lives]]. | + | Q.: “There is a [[tradition]] of reading ‘The [[Book]] of [[Liberation]] through Hearing in the [[Bardo]]’ to [[people]] who have [[died]]. I [[wonder]] how helpful this is?” TR: When someone has [[died]] and is in the [[bardo]], they have miraculous [[powers]], e.g., they are {{Wiki|clairvoyant}}. This means that if we read this [[book]] to them, they will understand and [[experience]] it. This [[book]] is a [[pointing-out instruction]] for those who are in the [[bardo]] between [[lives]]. |

The [[Painful]] [[Bardo]] of Dying | The [[Painful]] [[Bardo]] of Dying | ||

| − | We discussed the first of the four [[bardos]], the natural [[bardo]] of [[life]]. The [[reason]] the [[appearance]] of this [[life]] is called a [[bardo]], an ‘[[in-between state]],’ is because it covers the period of [[time]] while we have this [[body]]. This [[body]] acts as a support for us. It enables us to practice for the next [[bardo]]. After preparing for it in this [[life]], we will not be overtaken by {{Wiki|fear}} and [[suffering]] when the next [[bardo]], the state in-between [[lives]], appears to us. | + | We discussed the first of the four [[bardos]], the natural [[bardo]] of [[life]]. The [[reason]] the [[appearance]] of this [[life]] is called a [[bardo]], an ‘[[in-between state]],’ is because it covers the period of [[time]] while we have this [[body]]. This [[body]] acts as a support for us. It enables us to practice for the next [[bardo]]. After preparing for it in this [[life]], we will not be overtaken by {{Wiki|fear}} and [[suffering]] when the next [[bardo]], the [[state]] in-between [[lives]], appears to us. |

The second [[bardo]] we are going to discuss is the [[painful]] [[bardo of dying]]. The [[reason]] for this [[name]] is the particular {{Wiki|fear}}, {{Wiki|worry}}, and [[suffering]] that we [[experience]] as the [[body]] that we are so [[attached]] to begins to disintegrate. Our [[attachment]] to our [[body]] [[causes]] us {{Wiki|distinct}} [[suffering]] as we [[die]]. Training for this [[experience]] enables us to prepare ourselves by {{Wiki|learning}} what to expect. As the [[painful]] [[bardo of dying]] appears to us, we will understand what is happening and not only avoid {{Wiki|worry}} but also make the most of the opportunity it presents to us. | The second [[bardo]] we are going to discuss is the [[painful]] [[bardo of dying]]. The [[reason]] for this [[name]] is the particular {{Wiki|fear}}, {{Wiki|worry}}, and [[suffering]] that we [[experience]] as the [[body]] that we are so [[attached]] to begins to disintegrate. Our [[attachment]] to our [[body]] [[causes]] us {{Wiki|distinct}} [[suffering]] as we [[die]]. Training for this [[experience]] enables us to prepare ourselves by {{Wiki|learning}} what to expect. As the [[painful]] [[bardo of dying]] appears to us, we will understand what is happening and not only avoid {{Wiki|worry}} but also make the most of the opportunity it presents to us. | ||

| Line 75: | Line 174: | ||

There are three different types of [[people]] who [[experience]] the [[painful]] [[bardo of dying]]: those who have completely perfected their [[Dharma]] practice; those who are somewhere in the middle, they are [[yogis]] but haven’t achieved the same level of [[realization]]; and thirdly, ordinary {{Wiki|individuals}}. The first type of being, those who have perfected their [[meditation]], do not have to [[experience]] this [[bardo]]. They do not have to go through the [[painful]] process of dying but can [[manifest]] the [[pure lands]] while still connected to their [[bodies]]. The second type, the middling sort of [[yogi]], has had some [[experience]] in the [[development stage]] of [[meditation]], but they have not gone as far as they could go. This means that they must go through the process of dying, but they do not [[experience]] any [[suffering]] while this happens. The third group of [[beings]], ordinary {{Wiki|individuals}}, groups together two types of [[people]]: [[yogis]] with less [[realization]] and everyday, ordinary {{Wiki|individuals}}. It is for these [[people]] that these teachings are particularly pertinent. The [[people]] in this third group can use these teachings to prepare themselves for the [[painful]] [[bardo]] of [[death]]. If they know what is going to happen in this [[bardo]] – the [[appearances]] they are going to see, what the process of dying is going to be like –, they will be less afraid and therefore have to endure less. This is why we learn the process of the stages of [[dissolution]], so that we know what is going to happen. [[Knowing]] what will happen as we [[die]] enables us to stay [[calm]] and keep our [[mind]] {{Wiki|stable}} then. Having a {{Wiki|stable}} [[mind]] as we [[experience]] this [[bardo]] eliminates much of the [[suffering]] usually associated with it. | There are three different types of [[people]] who [[experience]] the [[painful]] [[bardo of dying]]: those who have completely perfected their [[Dharma]] practice; those who are somewhere in the middle, they are [[yogis]] but haven’t achieved the same level of [[realization]]; and thirdly, ordinary {{Wiki|individuals}}. The first type of being, those who have perfected their [[meditation]], do not have to [[experience]] this [[bardo]]. They do not have to go through the [[painful]] process of dying but can [[manifest]] the [[pure lands]] while still connected to their [[bodies]]. The second type, the middling sort of [[yogi]], has had some [[experience]] in the [[development stage]] of [[meditation]], but they have not gone as far as they could go. This means that they must go through the process of dying, but they do not [[experience]] any [[suffering]] while this happens. The third group of [[beings]], ordinary {{Wiki|individuals}}, groups together two types of [[people]]: [[yogis]] with less [[realization]] and everyday, ordinary {{Wiki|individuals}}. It is for these [[people]] that these teachings are particularly pertinent. The [[people]] in this third group can use these teachings to prepare themselves for the [[painful]] [[bardo]] of [[death]]. If they know what is going to happen in this [[bardo]] – the [[appearances]] they are going to see, what the process of dying is going to be like –, they will be less afraid and therefore have to endure less. This is why we learn the process of the stages of [[dissolution]], so that we know what is going to happen. [[Knowing]] what will happen as we [[die]] enables us to stay [[calm]] and keep our [[mind]] {{Wiki|stable}} then. Having a {{Wiki|stable}} [[mind]] as we [[experience]] this [[bardo]] eliminates much of the [[suffering]] usually associated with it. | ||

| − | The [[painful]] [[bardo]] of [[death]] is a process of [[dissolution]]. When we [[die]], this [[body]] of ours goes through a twofold [[dissolution]] process; the external [[elements]] dissolve and the internal [[mind]] dissolves. The external [[elements]] dissolve first; the [[earth]], [[fire]], [[air]], and [[consciousness]] of our [[body]] [[dies]]. When our [[bodies]] were first formed, it was through the combination of these [[elements]]. It was through the combining of [[consciousness]], [[air]], [[fire]], [[water]], and [[earth]] that our [[physical body]] came into being, and it is through the perpetuation of a relationship between these [[elements]] that we are alive now. Eventually, however, these [[elements]] will dissolve and our [[body]] will [[die]]. In the beginning, middle, and end, our [[physical]] [[existence]] is [[dependent upon]] the combination of these [[elements]]. | + | The [[painful]] [[bardo]] of [[death]] is a process of [[dissolution]]. When we [[die]], this [[body]] of ours goes through a twofold [[dissolution]] process; the external [[elements]] dissolve and the internal [[mind]] dissolves. The external [[elements]] dissolve first; the [[earth]], [[fire]], [[air]], and [[consciousness]] of our [[body]] [[dies]]. When our [[bodies]] were first formed, it was through the combination of these [[elements]]. It was through the [[combining]] of [[consciousness]], [[air]], [[fire]], [[water]], and [[earth]] that our [[physical body]] came into being, and it is through the perpetuation of a relationship between these [[elements]] that we are alive now. Eventually, however, these [[elements]] will dissolve and our [[body]] will [[die]]. In the beginning, middle, and end, our [[physical]] [[existence]] is [[dependent upon]] the combination of these [[elements]]. |

The dying process is the reversal of the process of becoming that began our [[life]]. We began this [[life]] through our {{Wiki|confusion}}. Having not [[realized]] the [[emptiness]] {{Wiki|nature}} of all [[phenomena]], confused images gradually grew clearer and clearer to us, until finally they gelled into the [[appearance]] of our [[life]]. This {{Wiki|confusion}} appears very clearly to us; it is what we [[experience]] as our [[life]]. When we [[die]], this confused apparition gradually dissolves along with the [[elements]]. The [[dissolution]] of this {{Wiki|confusion}} means that the [[emptiness]] {{Wiki|nature}} of all [[phenomena]], the [[emptiness]] {{Wiki|nature}} of our [[minds]]s clearer and clearer until finally the {{Wiki|luminous}} [[bardo of dharmata]] (‘[[dharma nature]]’) clearly appears to us. Those who have perfected their [[meditation]] [[recognize]] this [[bardo]] “like a mother meeting a child,” which is to say, quickly, easily and comfortably. Those of us who do not have this [[realization]] will not [[recognize]] this {{Wiki|luminous}} [[bardo of dharmata]]. Instead, through [[ignorance]], we’ll start to [[experience]] other confused [[imagery]], which in turn will become more intense and clear until crystallized into our next [[life]]. | The dying process is the reversal of the process of becoming that began our [[life]]. We began this [[life]] through our {{Wiki|confusion}}. Having not [[realized]] the [[emptiness]] {{Wiki|nature}} of all [[phenomena]], confused images gradually grew clearer and clearer to us, until finally they gelled into the [[appearance]] of our [[life]]. This {{Wiki|confusion}} appears very clearly to us; it is what we [[experience]] as our [[life]]. When we [[die]], this confused apparition gradually dissolves along with the [[elements]]. The [[dissolution]] of this {{Wiki|confusion}} means that the [[emptiness]] {{Wiki|nature}} of all [[phenomena]], the [[emptiness]] {{Wiki|nature}} of our [[minds]]s clearer and clearer until finally the {{Wiki|luminous}} [[bardo of dharmata]] (‘[[dharma nature]]’) clearly appears to us. Those who have perfected their [[meditation]] [[recognize]] this [[bardo]] “like a mother meeting a child,” which is to say, quickly, easily and comfortably. Those of us who do not have this [[realization]] will not [[recognize]] this {{Wiki|luminous}} [[bardo of dharmata]]. Instead, through [[ignorance]], we’ll start to [[experience]] other confused [[imagery]], which in turn will become more intense and clear until crystallized into our next [[life]]. | ||

| − | The whole process of [[dissolution]] begins at the [[navel]] centre. The structure of the [[elements]] that make up our [[body]] is influenced by the channels, [[winds]], and [[chakras]] (‘circular | + | The whole process of [[dissolution]] begins at the [[navel]] centre. The {{Wiki|structure}} of the [[elements]] that make up our [[body]] is influenced by the [[channels]], [[winds]], and [[chakras]] (‘circular [[channels]]’) within our [[bodies]]. We have five main [[chakras]]: at the {{Wiki|crown}} of our head, in our {{Wiki|throat}}, in our [[heart]] centre, in our [[navel]], and in the secret place. As the [[chakras]] are supported by the body’s [[winds]], the [[winds]]’ reversal [[causes]] them to dissolve. There are said to be five different types of [[winds]] that pass through these [[channels]]. The first to reverse and dissolve is the equally-abiding [[wind]], so called because it pervades the [[body]]. When it reverses and dissolves, our [[body]] loses its heat and we are unable to digest any [[food]]. Its [[dissolution]] is followed by the [[dissolution]] of the life-supporting [[wind]], then the downward-clearing [[wind]], and likewise the other two [[winds]], the upward-clearing [[wind]] and the [[wind]] that stabilizes warmth. |

| − | When these [[winds]] have dissolved, the [[navel]] [[chakra]] starts to dissolve. This is accompanied by external, internal, and secret [[signs]]. The external [[signs]] are those that can be [[perceived]] by others. If we were to watch another [[person]] dying, we would see these [[signs]]. We could see, for example, that their face was losing its {{Wiki|colour}}, that they had become pallid, and that their [[body]] was losing its strength. The internal [[signs]] are those [[experienced]] by the dying [[person]] himself or herself. The internal sign of the [[dissolution]] of this [[chakra]], for example, is that the [[mind]] will grow unclear and the dying [[person]] will [[feel]] depressed. The secret [[signs]] are those that can be [[recognized]] by [[meditators]]. With the [[dissolution]] of this [[chakra]], for example, the [[meditator]] would notice that the [[dharmata]] appears alternately clearly and hazily. It will be [[experienced]] like a {{Wiki|mirage}} or an [[illusion]], in and out of focus. Gradually, as the dying process progresses, the [[appearance]] of the [[dharmata]] becomes clearer and clearer. | + | When these [[winds]] have dissolved, the [[navel]] [[chakra]] starts to dissolve. This is accompanied by external, internal, and secret [[signs]]. The external [[signs]] are those that can be [[perceived]] by others. If we were to watch another [[person]] dying, we would see these [[signs]]. We could see, for example, that their face was losing its {{Wiki|colour}}, that they had become pallid, and that their [[body]] was losing its strength. The internal [[signs]] are those [[experienced]] by the dying [[person]] himself or herself. The internal sign of the [[dissolution]] of this [[chakra]], for example, is that the [[mind]] will grow unclear and the dying [[person]] will [[feel]] {{Wiki|depressed}}. The secret [[signs]] are those that can be [[recognized]] by [[meditators]]. With the [[dissolution]] of this [[chakra]], for example, the [[meditator]] would notice that the [[dharmata]] appears alternately clearly and hazily. It will be [[experienced]] like a {{Wiki|mirage}} or an [[illusion]], in and out of focus. Gradually, as the dying process progresses, the [[appearance]] of the [[dharmata]] becomes clearer and clearer. |

The next [[chakra]] to dissolve is the one at the [[heart]] centre. At this point, the [[water element]] dissolves into the [[fire element]]. The external sign of this occurrence is that the nostrils and {{Wiki|nose}} become very dry. Internally, the dying [[person]] will [[feel]] irritable and hesitant. The secret sign for [[meditators]] is a smoke-like [[appearance]]. | The next [[chakra]] to dissolve is the one at the [[heart]] centre. At this point, the [[water element]] dissolves into the [[fire element]]. The external sign of this occurrence is that the nostrils and {{Wiki|nose}} become very dry. Internally, the dying [[person]] will [[feel]] irritable and hesitant. The secret sign for [[meditators]] is a smoke-like [[appearance]]. | ||

| − | The next [[chakra]] to dissolve is the one at the {{Wiki|throat}}, and its [[dissolution]] is accompanied by the [[dissolution]] of the [[fire element]] into the [[air element]]. The external sign is that the [[body]] loses its heat. The internal sign is that the dying person’s [[mind]] is alternately clear and unclear. The secret sign is an [[appearance]] of red fireflies [[dancing]] about in the sky in front of us. This sign means that the [[dharmata]] can be [[perceived]] a little clearer than in the previous stages. | + | The next [[chakra]] to dissolve is the one at the {{Wiki|throat}}, and its [[dissolution]] is accompanied by the [[dissolution]] of the [[fire element]] into the [[air element]]. The external sign is that the [[body]] loses its heat. The internal sign is that the dying person’s [[mind]] is alternately clear and unclear. The secret sign is an [[appearance]] of [[red]] fireflies [[dancing]] about in the sky in front of us. This sign means that the [[dharmata]] can be [[perceived]] a little clearer than in the previous stages. |

Next, the [[chakra]] in the secret area of our genitals dissolves. At this [[time]], the [[air element]] dissolves into [[consciousness]]. The external sign of this is that {{Wiki|breathing}} becomes very difficult. Sometimes there is a long [[space]] between inhalations, and the inhalations are forced and difficult. The internal sign is that the [[mind]] becomes very unclear and it is very difficult to {{Wiki|perceive}} external [[forms]]. The secret sign is an image of a flaming torch. | Next, the [[chakra]] in the secret area of our genitals dissolves. At this [[time]], the [[air element]] dissolves into [[consciousness]]. The external sign of this is that {{Wiki|breathing}} becomes very difficult. Sometimes there is a long [[space]] between inhalations, and the inhalations are forced and difficult. The internal sign is that the [[mind]] becomes very unclear and it is very difficult to {{Wiki|perceive}} external [[forms]]. The secret sign is an image of a flaming torch. | ||

| Line 91: | Line 190: | ||

At this point, the [[five elements]] have all dissolved and as they were the support for the [[five senses]], we can also say that the [[senses]] have dissolved. The eye’s [[sense]] {{Wiki|faculty}} has dissolved, so we can no longer see external [[forms]]. The nose’s [[sense]] {{Wiki|faculty}} has dissolved, so we can no longer {{Wiki|smell}} and so forth. We are no longer able to {{Wiki|perceive}} the external [[world]]. Lastly, the [[consciousness]] dissolves into [[space]] and the outer [[dissolution]] is complete. This final [[dissolution]] marks the point-of-no-return. Up until this point, the process can be reversed. If the {{Wiki|illness}} or injury that [[caused]] it can be treated, the dying process can be thwarted and the [[person]] can continue to [[live]]. As we move onto the process of the internal [[dissolution]], though, there’s no possibility of reversal. This internal [[dissolution]] is the [[dissolution]] of the [[thoughts]], and after it begins we cannot be revived. | At this point, the [[five elements]] have all dissolved and as they were the support for the [[five senses]], we can also say that the [[senses]] have dissolved. The eye’s [[sense]] {{Wiki|faculty}} has dissolved, so we can no longer see external [[forms]]. The nose’s [[sense]] {{Wiki|faculty}} has dissolved, so we can no longer {{Wiki|smell}} and so forth. We are no longer able to {{Wiki|perceive}} the external [[world]]. Lastly, the [[consciousness]] dissolves into [[space]] and the outer [[dissolution]] is complete. This final [[dissolution]] marks the point-of-no-return. Up until this point, the process can be reversed. If the {{Wiki|illness}} or injury that [[caused]] it can be treated, the dying process can be thwarted and the [[person]] can continue to [[live]]. As we move onto the process of the internal [[dissolution]], though, there’s no possibility of reversal. This internal [[dissolution]] is the [[dissolution]] of the [[thoughts]], and after it begins we cannot be revived. | ||

| − | This final process of [[dissolution]] involves the white [[element]] that we received from our father, which is at the {{Wiki|crown}} of our heads, and the red [[element]] that we received from our mother, which is at our [[navel]]. While we are alive, the strength of the [[winds]] within our [[body]] keeps these two [[elements]] in place, but when the [[winds]] are weakened and reverse as we [[die]], these two [[elements]] can no longer stay apart; they begin to move towards each other. Gradually, they make their way towards each other and finally meet at the [[heart]] centre. The white [[element]] we received from our father begins this process. When it can no longer be held up, it descends slowly down towards our [[heart]] centre. As this happens, we [[experience]] the [[appearance]] of whiteness. Next, as the red [[element]] that we received from our mother can no longer be held down by these same [[winds]], it begins to rise up. This process is accompanied by the [[appearance]] of redness. When these two [[elements]] meet at the [[heart]] centre, blackness appears. It is through this process of [[dissolution]] that the internal [[thoughts]] start to dissolve. If we were to examine our [[thoughts]] very carefully, we would be able to classify them into 80 different types and again into three main categories that are associated with these three stages of [[dissolution]]. As the white [[element]] that we obtained from our father [[beings]] to descend to the [[heart]] centre, those [[states of mind]] associated with [[anger]] and [[hatred]] dissolve. As the red [[element]] that we obtained from our mother ascends, [[passionate]] [[thoughts]] dissolve. Finally, as the white and red [[elements]] come together in the [[heart]] centre and we [[experience]] blackness, [[ignorant]] [[mental]] stages dissolve. When this [[dissolution]] is finished, we [[experience]] the next [[bardo]], the {{Wiki|luminous}} [[bardo of dharmata]]. | + | This final process of [[dissolution]] involves the white [[element]] that we received from our father, which is at the {{Wiki|crown}} of our heads, and the [[red]] [[element]] that we received from our mother, which is at our [[navel]]. While we are alive, the strength of the [[winds]] within our [[body]] keeps these two [[elements]] in place, but when the [[winds]] are weakened and reverse as we [[die]], these two [[elements]] can no longer stay apart; they begin to move towards each other. Gradually, they make their way towards each other and finally meet at the [[heart]] centre. The white [[element]] we received from our father begins this process. When it can no longer be held up, it descends slowly down towards our [[heart]] centre. As this happens, we [[experience]] the [[appearance]] of whiteness. Next, as the [[red]] [[element]] that we received from our mother can no longer be held down by these same [[winds]], it begins to rise up. This process is accompanied by the [[appearance]] of redness. When these two [[elements]] meet at the [[heart]] centre, blackness appears. It is through this process of [[dissolution]] that the internal [[thoughts]] start to dissolve. If we were to examine our [[thoughts]] very carefully, we would be able to classify them into 80 different types and again into three main categories that are associated with these three stages of [[dissolution]]. As the white [[element]] that we obtained from our father [[beings]] to descend to the [[heart]] centre, those [[states of mind]] associated with [[anger]] and [[hatred]] dissolve. As the [[red]] [[element]] that we obtained from our mother ascends, [[passionate]] [[thoughts]] dissolve. Finally, as the white and [[red]] [[elements]] come together in the [[heart]] centre and we [[experience]] blackness, [[ignorant]] [[mental]] stages dissolve. When this [[dissolution]] is finished, we [[experience]] the next [[bardo]], the {{Wiki|luminous}} [[bardo of dharmata]]. |

So, how do we prepare for the [[painful]] [[bardo of dying]]? The first thing we need to do is to understand [[impermanence]] and become familiar with the [[idea]] that [[death]] is inevitable, but the [[time]] of [[death]] is unknown. [[Knowing]] what will happen to us when we [[die]] will also be helpful, so we should study the teachings on the [[bardos]]. As we begin to [[die]], there are also quite a few other things we can do. To begin with, we can let go of everything that we are [[attached]] to. We should [[imagine]] ourselves [[offering]] all our [[worldly]] {{Wiki|possessions}} to the [[Three Jewels]]. As we are dying, we may also find ourselves worrying about work that we haven’t been able to finish, but at this stage we should forget about our unfinished business. None of these things – even our relatives and friends – can help us very much at this stage anyway. We have to leave them; we have to go [[beyond]] this [[life]] without them, so being [[attached]] to them will [[cause]] us even more [[suffering]]. If we have a close [[friend]] who [[understands]] the dying practice, has the same [[samaya]] [[commitments]] as we do, and can therefore help us, we should try and keep them near. But if our relatives and friends are crying loudly and carrying on, their presence will not help us, and we should ask them to leave. This kind of {{Wiki|behaviour}} will only serve to create [[attachment]] in us and therefore [[cause]] us to [[experience]] more [[suffering]]. As we go through this process, we need to remember the instructions regarding [[death]] and try to put them into practice. We need to try and stay {{Wiki|aware}}. If we are distracted, we may be pulled towards [[suffering]] and a bad [[birth]]. | So, how do we prepare for the [[painful]] [[bardo of dying]]? The first thing we need to do is to understand [[impermanence]] and become familiar with the [[idea]] that [[death]] is inevitable, but the [[time]] of [[death]] is unknown. [[Knowing]] what will happen to us when we [[die]] will also be helpful, so we should study the teachings on the [[bardos]]. As we begin to [[die]], there are also quite a few other things we can do. To begin with, we can let go of everything that we are [[attached]] to. We should [[imagine]] ourselves [[offering]] all our [[worldly]] {{Wiki|possessions}} to the [[Three Jewels]]. As we are dying, we may also find ourselves worrying about work that we haven’t been able to finish, but at this stage we should forget about our unfinished business. None of these things – even our relatives and friends – can help us very much at this stage anyway. We have to leave them; we have to go [[beyond]] this [[life]] without them, so being [[attached]] to them will [[cause]] us even more [[suffering]]. If we have a close [[friend]] who [[understands]] the dying practice, has the same [[samaya]] [[commitments]] as we do, and can therefore help us, we should try and keep them near. But if our relatives and friends are crying loudly and carrying on, their presence will not help us, and we should ask them to leave. This kind of {{Wiki|behaviour}} will only serve to create [[attachment]] in us and therefore [[cause]] us to [[experience]] more [[suffering]]. As we go through this process, we need to remember the instructions regarding [[death]] and try to put them into practice. We need to try and stay {{Wiki|aware}}. If we are distracted, we may be pulled towards [[suffering]] and a bad [[birth]]. | ||

| − | We should also try and maintain the [[meditation]] practices that we did during our [[lifetime]]. If we practiced [[Mahamudra]] while we lived, then as we [[die]] we should try and remember that all things are the [[appearance]] of our own [[mind]] – which is by {{Wiki|nature}} emptiness-clarity – and [[rest]] our [[mind]] in the [[appearances]] we [[experience]] while dying. If we practiced [[Dzogchen]] (‘[[Great Perfection]]’), then we should remember the constitution of the drops and channels. This is also what we should bring to [[mind]] if we are a [[practitioner]] of the [[six yogas]]. If we are familiar with [[development stage]] [[yogas]], if we have a [[yidam]], then we should [[meditate]] on this. If our [[meditation]] [[deity]] is [[Chenrezig]], for example, as we [[die]] we should maintain our focus on the [[body]] of [[Chenrezig]] that abides within our [[body]]. If we haven’t done any [[meditation]] practices at this level while we were alive, we should [[concentrate]] on our aspirations, asking the [[Three Jewels]] for help and [[visualizing]] ourselves making [[offerings]] to them. | + | We should also try and maintain the [[meditation]] practices that we did during our [[lifetime]]. If we practiced [[Mahamudra]] while we lived, then as we [[die]] we should try and remember that all things are the [[appearance]] of our [[own]] [[mind]] – which is by {{Wiki|nature}} emptiness-clarity – and [[rest]] our [[mind]] in the [[appearances]] we [[experience]] while dying. If we practiced [[Dzogchen]] (‘[[Great Perfection]]’), then we should remember the constitution of the drops and [[channels]]. This is also what we should bring to [[mind]] if we are a [[practitioner]] of the [[six yogas]]. If we are familiar with [[development stage]] [[yogas]], if we have a [[yidam]], then we should [[meditate]] on this. If our [[meditation]] [[deity]] is [[Chenrezig]], for example, as we [[die]] we should maintain our focus on the [[body]] of [[Chenrezig]] that abides within our [[body]]. If we haven’t done any [[meditation]] practices at this level while we were alive, we should [[concentrate]] on our [[aspirations]], asking the [[Three Jewels]] for help and [[visualizing]] ourselves making [[offerings]] to them. |