Difference between revisions of "Chod"

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | '''[[Chöd]]''' ([[Tibetan]]: {{BigTibetan|[[གཅོད]]}}, [[Wylie]]: [[gcod]] lit. 'to sever'), is a [[spiritual]] practice found primarily in [[Tibetan Buddhism]]. Also known as "[[Cutting Through the Ego]]," the practice is based on the [[Prajñāpāramitā sutra|Prajñāpāramitā sutra]]. It combines [[prajñapāramitā]] [[philosophy]] with specific [[meditation]] methods and a [[tantric]] [[ritual]]. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | '''[[Chöd]]''' ([[Tibetan]]: {{BigTibetan|[[གཅོད]]}}, [[Wylie]]: [[gcod]] lit. 'to sever'), is a [[spiritual]] practice found primarily in [[Tibetan Buddhism]]. Also known as "[[Cutting Through the Ego]]," the practice is based on the [[Prajñāpāramitā sutra|Prajñāpāramitā sutra]]. It combines [[prajñapāramitā]] [[philosophy]] with specific [[meditation]] [[methods]] and a [[tantric]] [[ritual]]. | ||

| + | |||

== Nomenclature, {{Wiki|orthography}} and {{Wiki|etymology}} == | == Nomenclature, {{Wiki|orthography}} and {{Wiki|etymology}} == | ||

| + | |||

([[Tibetan]]: {{BigTibetan|[[གཅོད་སྒྲུབ་ཐབས་]]}} [[gcod sgrub thabs]]; [[Sanskrit]]: [[छेद साधना]] [[cheda-sādhana]]; both literally "[[cutting practice]]"), pronounced [[chö]] (the d is [[silent]]). | ([[Tibetan]]: {{BigTibetan|[[གཅོད་སྒྲུབ་ཐབས་]]}} [[gcod sgrub thabs]]; [[Sanskrit]]: [[छेद साधना]] [[cheda-sādhana]]; both literally "[[cutting practice]]"), pronounced [[chö]] (the d is [[silent]]). | ||

| + | |||

== [[Indian]] Antecedents == | == [[Indian]] Antecedents == | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

:“...[[Chöd]] was never a unique, monolithic [[tradition]]. One should really speak of [[Chöd]] [[traditions]] and [[lineages]] since [[Chöd]] has never constituted a school.” | :“...[[Chöd]] was never a unique, monolithic [[tradition]]. One should really speak of [[Chöd]] [[traditions]] and [[lineages]] since [[Chöd]] has never constituted a school.” | ||

| − | A [[form]] of [[Chöd]] was practiced in [[India]] by [[Buddhist]] [[mahāsiddhas]], prior to the 10th Century. However, [[Chöd]] as practiced today developed from the {{Wikidictionary|entwined}} [[traditions]] of the early [[Indian]] [[tantric practices]] transmitted to [[Tibet]] and the [[Bonpo]] and [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[Vajrayāna]] [[lineages]]. Besides the [[Bonpo]], there are two main [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[Chöd]] | + | A [[form]] of [[Chöd]] was practiced in [[India]] by [[Buddhist]] [[mahāsiddhas]], prior to the 10th Century. However, [[Chöd]] as practiced today developed from the {{Wikidictionary|entwined}} [[traditions]] of the early [[Indian]] [[tantric practices]] transmitted to [[Tibet]] and the [[Bonpo]] and [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[Vajrayāna]] [[lineages]]. Besides the [[Bonpo]], there are two main [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[Chöd]] |

| − | The [[Chöd]], as an internalization of an outer [[ritual]], involves a [[form]] of self-sacrifice: the [[practitioner]] [[visualizes]] their [[own]] [[body]] as the [[offering]] at a [[ganachakra]] or [[tantric]] feast. The {{Wiki|purpose}} of the practice is to engender a [[sense]] of victory and [[fearlessness]]. These two qualities are represented iconographically by the [[dhvaja]], or [[victory banner]] and the [[kartika]], or [[ritual]] knife. The [[banner]] [[symbolizes]] [[overcoming]] {{Wiki|obstacles}} and the knife [[symbolizes]] cutting through the [[ego]]. Since {{Wiki|fearful}} or [[painful]] situations help the practitioner's work of cutting through [[attachment]] to the [[self]], such situations may be cultivated. [[Machig Labdrön]] said: "To consider adversity as a [[friend]] is the instruction of [[Chöd]]". | + | [[traditions]], the "Mother" and "Father" [[lineages]]. In [[Tibetan tradition]], [[Dampa Sangye]] is known as the [[Father of Chöd]] and [[Machig Labdron]], founder of the [[Mahāmudra]] [[Chöd lineages]], as the [[Mother of Chöd]]. [[Chöd]] developed outside the [[monastic]] system. It was subsequently adopted by the four main [[schools of Tibetan Buddhism]]. |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | The [[Chöd]], as an internalization of an outer [[ritual]], involves a [[form]] of self-sacrifice: the [[practitioner]] [[visualizes]] their [[own]] [[body]] as the [[offering]] at a [[ganachakra]] or [[tantric]] feast. The {{Wiki|purpose}} of the practice is to engender a [[sense]] of victory and [[fearlessness]]. These two qualities are represented iconographically by the [[dhvaja]], or [[victory banner]] and the [[kartika]], or | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[ritual]] knife. The [[banner]] [[symbolizes]] [[overcoming]] {{Wiki|obstacles}} and the knife [[symbolizes]] cutting through the [[ego]]. Since {{Wiki|fearful}} or [[painful]] situations help the practitioner's work of cutting through [[attachment]] to the [[self]], such situations may be cultivated. [[Machig Labdrön]] said: "To consider adversity as a [[friend]] is the instruction of [[Chöd]]". | ||

| Line 18: | Line 39: | ||

: "{{BigTibetan|[[ཀུ་སུ་ལུ་པ]]}} [[ku-su-lu-pa]] ¿ is a [[word]] of [[Tantrik mysticism]], its proper [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|equivalent}} being {{BigTibetan|[[གཅོད་པ]]}} [[gcod-pa]], the [[art of exorcism]]. The [[mystic Tantrik rites]] of the [[Avadhauts]], called [[Avadhūtipa]] in [[Tibet]], [[exist]] in [[India]]." | : "{{BigTibetan|[[ཀུ་སུ་ལུ་པ]]}} [[ku-su-lu-pa]] ¿ is a [[word]] of [[Tantrik mysticism]], its proper [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|equivalent}} being {{BigTibetan|[[གཅོད་པ]]}} [[gcod-pa]], the [[art of exorcism]]. The [[mystic Tantrik rites]] of the [[Avadhauts]], called [[Avadhūtipa]] in [[Tibet]], [[exist]] in [[India]]." | ||

| + | |||

NB: ¿ = [[kusulu]] or [[kusulupa]] ([[Sanskrit]]; [[Tibetan]] loanword) that is studying texts rarely whilst focusing on [[meditation]] and praxis. Often used disparagingly by [[pandits]]. | NB: ¿ = [[kusulu]] or [[kusulupa]] ([[Sanskrit]]; [[Tibetan]] loanword) that is studying texts rarely whilst focusing on [[meditation]] and praxis. Often used disparagingly by [[pandits]]. | ||

| + | |||

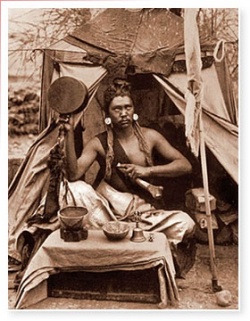

[[Avadhūtas]], or '[[mad saints]],' are well known for their '[[crazy wisdom]].' [[Chöd]] practitioners ([[chödpas]]) are a type of [[avadhūta]] particularly respected, detested, feared or held in awe due to their role as denizens of the [[charnel ground]]. Edou says they were often associated with the role of {{Wiki|shaman}} and {{Wiki|exorcist}}: | [[Avadhūtas]], or '[[mad saints]],' are well known for their '[[crazy wisdom]].' [[Chöd]] practitioners ([[chödpas]]) are a type of [[avadhūta]] particularly respected, detested, feared or held in awe due to their role as denizens of the [[charnel ground]]. Edou says they were often associated with the role of {{Wiki|shaman}} and {{Wiki|exorcist}}: | ||

| + | |||

: "The [[Chödpa's]] very [[lifestyle]] on the fringe of {{Wiki|society}} - dwelling in the [[solitude]] of [[burial grounds]] and haunted places, added to the mad {{Wiki|behavior}} and [[contact]] with the [[world]] of {{Wiki|darkness}} and {{Wiki|mystery}} - was enough for credulous [[people]] to [[view]] the [[Chödpa]] in a role usually attributed to {{Wiki|shamans}} and other exorcists, an assimilation which also happened to {{Wiki|medieval European}} shepherds. Only someone who has visited one of {{Wiki|Tibet's}} charnel fields and witnessed the [[offering]] of a corpse to the vultures may be able to understand the full impact of what the [[Chöd]] [[tradition]] refers to as places that inspire {{Wiki|terror}}. | : "The [[Chödpa's]] very [[lifestyle]] on the fringe of {{Wiki|society}} - dwelling in the [[solitude]] of [[burial grounds]] and haunted places, added to the mad {{Wiki|behavior}} and [[contact]] with the [[world]] of {{Wiki|darkness}} and {{Wiki|mystery}} - was enough for credulous [[people]] to [[view]] the [[Chödpa]] in a role usually attributed to {{Wiki|shamans}} and other exorcists, an assimilation which also happened to {{Wiki|medieval European}} shepherds. Only someone who has visited one of {{Wiki|Tibet's}} charnel fields and witnessed the [[offering]] of a corpse to the vultures may be able to understand the full impact of what the [[Chöd]] [[tradition]] refers to as places that inspire {{Wiki|terror}}. | ||

| + | |||

=={{Wiki|Iconography}} == | =={{Wiki|Iconography}} == | ||

| + | |||

In [[Chöd]], the {{Wiki|adept}} [[symbolically]] offers the flesh of their [[body]] in a [[form]] of [[gaṇacakra]] or [[tantric feast]]. Iconographically, the {{Wiki|skin}} of the practitioner's [[body]] may represent surface [[reality]] or [[maya]]. It is cut from [[bones]] that represent the true [[reality]] of the [[mindstream]]. Some commentators see the [[Chöd]] [[ritual]] as {{Wiki|cognate}} with the prototypical [[initiation]] of a {{Wiki|shaman}}. [[Traditionally]], [[Chöd]] is regarded as challenging, potentially [[dangerous]] and inappropriate for some practitioners. | In [[Chöd]], the {{Wiki|adept}} [[symbolically]] offers the flesh of their [[body]] in a [[form]] of [[gaṇacakra]] or [[tantric feast]]. Iconographically, the {{Wiki|skin}} of the practitioner's [[body]] may represent surface [[reality]] or [[maya]]. It is cut from [[bones]] that represent the true [[reality]] of the [[mindstream]]. Some commentators see the [[Chöd]] [[ritual]] as {{Wiki|cognate}} with the prototypical [[initiation]] of a {{Wiki|shaman}}. [[Traditionally]], [[Chöd]] is regarded as challenging, potentially [[dangerous]] and inappropriate for some practitioners. | ||

| + | |||

=== [[Ritual]] [[objects]] === | === [[Ritual]] [[objects]] === | ||

| + | |||

Practitioners of the [[Chöd]] [[ritual]], [[Chödpa]], use a [[kangling]] or [[human thighbone trumpet]], and a [[Chöd drum]], a [[hand drum]] similar to but larger than the [[ḍamaru]] commonly used in [[Tibetan]] [[ritual]]. In a version of the [[Chöd]] [[sādhana]] of [[Jigme Lingpa]] from the [[Longchen Nyingthig]] [[terma]], five [[ritual]] knives ([[phurbas]]), are employed to demarcate the [[maṇḍala]] of the [[offering]] and to affix the [[five wisdoms]]. | Practitioners of the [[Chöd]] [[ritual]], [[Chödpa]], use a [[kangling]] or [[human thighbone trumpet]], and a [[Chöd drum]], a [[hand drum]] similar to but larger than the [[ḍamaru]] commonly used in [[Tibetan]] [[ritual]]. In a version of the [[Chöd]] [[sādhana]] of [[Jigme Lingpa]] from the [[Longchen Nyingthig]] [[terma]], five [[ritual]] knives ([[phurbas]]), are employed to demarcate the [[maṇḍala]] of the [[offering]] and to affix the [[five wisdoms]]. | ||

| + | |||

Key to the {{Wiki|iconography}} of [[Chöd]] is the hooked knife or {{Wiki|skin}} flail ([[kartika]]). A flail is an agricultural tool used for threshing to separate grains from their husks. Similarly, the [[kartika]] [[symbolically]] separates the [[body]] [[mind]] from the [[mindstream]]. The [[kartika]] [[imagery]] in the [[Chöd]] [[ritual]] provides the [[practitioner]] with an opportunity to realize [[Buddhist doctrine]]: | Key to the {{Wiki|iconography}} of [[Chöd]] is the hooked knife or {{Wiki|skin}} flail ([[kartika]]). A flail is an agricultural tool used for threshing to separate grains from their husks. Similarly, the [[kartika]] [[symbolically]] separates the [[body]] [[mind]] from the [[mindstream]]. The [[kartika]] [[imagery]] in the [[Chöd]] [[ritual]] provides the [[practitioner]] with an opportunity to realize [[Buddhist doctrine]]: | ||

[[File:Kartika_Knife.jpg|thumb|250px|Kartika or curved knife]] | [[File:Kartika_Knife.jpg|thumb|250px|Kartika or curved knife]] | ||

| + | |||

: The [[Kartika]] (Skt.) or [[curved knife]] [[symbolizes]] the cutting of [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[wisdom]] by the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] [[insight]] into [[emptiness]]. It is usually {{Wiki|present}} as a pair, together with the [[skullcup]], filled with [[wisdom]] [[nectar]]. On a more simple level, the [[skull]] is a reminder of (our) [[impermanence]]. Between the knife and the handle is a [[makara]]-head, a [[mythical]] monster. | : The [[Kartika]] (Skt.) or [[curved knife]] [[symbolizes]] the cutting of [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[wisdom]] by the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] [[insight]] into [[emptiness]]. It is usually {{Wiki|present}} as a pair, together with the [[skullcup]], filled with [[wisdom]] [[nectar]]. On a more simple level, the [[skull]] is a reminder of (our) [[impermanence]]. Between the knife and the handle is a [[makara]]-head, a [[mythical]] monster. | ||

| + | |||

=== [[Bone ornaments]] === | === [[Bone ornaments]] === | ||

| + | |||

A recurrent theme in the {{Wiki|iconography}} of the [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[tantras]] is a group of five or six [[bone ornaments]] ornamenting the [[bodies]] of various [[enlightened beings]] who appear in the texts. The [[Sanskrit]] includes the term [[mudrā]], meaning "[[seal]]". The [[Hevajra tantra]] associates the [[bone ornaments]] directly with the [[five wisdoms]], which also appear as the [[Five Dhyani Buddhas]]. These are explained in a commentary to the [[Hevajra tantra]] by [[Jamgön Kongtrul]]: | A recurrent theme in the {{Wiki|iconography}} of the [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[tantras]] is a group of five or six [[bone ornaments]] ornamenting the [[bodies]] of various [[enlightened beings]] who appear in the texts. The [[Sanskrit]] includes the term [[mudrā]], meaning "[[seal]]". The [[Hevajra tantra]] associates the [[bone ornaments]] directly with the [[five wisdoms]], which also appear as the [[Five Dhyani Buddhas]]. These are explained in a commentary to the [[Hevajra tantra]] by [[Jamgön Kongtrul]]: | ||

| + | |||

* the wheel-like {{Wiki|crown}} ornament (sometimes called "{{Wiki|crown}} [[jewel]]"), [[symbolic]] of [[Akṣobhya]] and [[mirror-like pristine awareness]] | * the wheel-like {{Wiki|crown}} ornament (sometimes called "{{Wiki|crown}} [[jewel]]"), [[symbolic]] of [[Akṣobhya]] and [[mirror-like pristine awareness]] | ||

| + | |||

* the earrings representing [[Amitābha]] and the [[pristine awareness]] of [[discernment]] | * the earrings representing [[Amitābha]] and the [[pristine awareness]] of [[discernment]] | ||

| + | |||

* the necklace [[symbolizing]] [[Ratnasambhāva]] and the [[pristine awareness]] of total [[sameness]] | * the necklace [[symbolizing]] [[Ratnasambhāva]] and the [[pristine awareness]] of total [[sameness]] | ||

| + | |||

* the bracelets and anklets [[symbolic]] of [[Vairocāna]] and the [[pristine awareness]] of the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] [[dimension]] of [[phenomena]] | * the bracelets and anklets [[symbolic]] of [[Vairocāna]] and the [[pristine awareness]] of the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] [[dimension]] of [[phenomena]] | ||

| + | |||

* the girdle [[symbolizing]] [[Amoghasiddhi]] and the accomplishing [[pristine awareness]] | * the girdle [[symbolizing]] [[Amoghasiddhi]] and the accomplishing [[pristine awareness]] | ||

| + | |||

* The sixth ornament sometimes referred to is ash from a [[cremation ground]] smeared on the [[body]]. | * The sixth ornament sometimes referred to is ash from a [[cremation ground]] smeared on the [[body]]. | ||

| + | |||

==Origins of the practice== | ==Origins of the practice== | ||

| − | Sources such as [[Stephen Beyer]] have described [[Machig Labdrön]] as the founder of the practice of [[Chöd]]. This is accurate in that she is the founder of the [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[Mahamudrā]] [[Chöd lineages]]. [[Machig Labdrön]] is credited with providing the [[name]] "[[Chöd]]" and developing unique approaches to the practice. {{Wiki|Biographies}} suggest it was transmitted to her via sources of the [[mahāsiddha]] and [[Tantric]] [[traditions]]. She did not found the [[Dzogchen]] [[lineages]], although they do [[recognize]] her, and she does not appear at all in the [[Bön]] [[Chöd lineages]]. Among the formative [[influences]] on [[Mahamudrā]] [[Chöd]] was [[Dampa Sangye's]] 'Pacification of [[Suffering]]'. | + | Sources such as [[Stephen Beyer]] have described [[Machig Labdrön]] as the founder of the practice of [[Chöd]]. This is accurate in that she is the founder of the [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[Mahamudrā]] [[Chöd lineages]]. [[Machig Labdrön]] is credited with providing the [[name]] "[[Chöd]]" and |

| + | |||

| + | developing unique approaches to the practice. {{Wiki|Biographies}} suggest it was transmitted to her via sources of the [[mahāsiddha]] and [[Tantric]] [[traditions]]. She did not found the [[Dzogchen]] [[lineages]], although they do [[recognize]] her, and she does not appear at all in the [[Bön]] [[Chöd lineages]]. Among the formative [[influences]] on [[Mahamudrā]] [[Chöd]] was [[Dampa Sangye's]] 'Pacification of [[Suffering]]'. | ||

| + | |||

===The [[transmission]] of [[Chöd]] to [[Tibet]]=== | ===The [[transmission]] of [[Chöd]] to [[Tibet]]=== | ||

| − | There are several [[Wikipedia:Hagiography|hagiographic]] accounts of how [[Chöd]] came to [[Tibet]]. One [[spiritual]] {{Wiki|biography}} asserts that shortly after [[Kamalaśīla]] won his famous [[debate]] with [[Moheyan]] as to whether [[Tibet]] should adopt the "sudden" route to [[enlightenment]] or his "[[gradual]]" route, [[Kamalaśīla]] used the technique of [[phowa]], transferring his [[mindstream]] to animate a corpse polluted with contagion in order to safely move the hazard it presented. As the [[mindstream]] of [[Kamalaśīla]] was otherwise engaged, a [[mahasiddha]] by the [[name]] of [[Padampa Sangye]] came across the vacant "[[physical]] basis" of [[Kamalaśīla]]. [[Padampa Sangye]], was not [[karmically]] blessed with an {{Wiki|aesthetic}} corporeal [[form]], and upon finding the very handsome and healthy [[empty]] [[body]] of [[Kamalaśīla]], which he assumed to be a newly [[dead]] fresh corpse, used [[phowa]] to transfer his [[own]] [[mindstream]] into [[Kamalaśīla's]] [[body]]. [[Padampa Sangye's]] [[mindstream]] in [[Kamalaśīla's]] [[body]] continued the [[ascent]] to the [[Himalaya]] and thereby transmitted the Pacification of [[Suffering]] teachings and the [[Indian]] [[form]] of [[Chöd]] which contributed to the [[Mahamudra]] [[Chöd]] of [[Machig Labdrön]]. The [[mindstream]] of [[Kamalaśīla]] was unable to return to his [[own]] [[body]] and so was forced to enter the vacant [[body]] of [[Padampa Sangye]]. | + | |

| + | There are several [[Wikipedia:Hagiography|hagiographic]] accounts of how [[Chöd]] came to [[Tibet]]. One [[spiritual]] {{Wiki|biography}} asserts that shortly after [[Kamalaśīla]] won his famous [[debate]] with [[Moheyan]] as to whether [[Tibet]] should adopt the "sudden" route to | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[enlightenment]] or his "[[gradual]]" route, [[Kamalaśīla]] used the technique of [[phowa]], transferring his [[mindstream]] to animate a corpse polluted with contagion in order to safely move the hazard it presented. As the [[mindstream]] of [[Kamalaśīla]] was otherwise engaged, a | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[mahasiddha]] by the [[name]] of [[Padampa Sangye]] came across the vacant "[[physical]] basis" of [[Kamalaśīla]]. [[Padampa Sangye]], was not [[karmically]] blessed with an {{Wiki|aesthetic}} corporeal [[form]], and upon finding the very handsome and healthy [[empty]] [[body]] of | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Kamalaśīla]], which he assumed to be a newly [[dead]] fresh corpse, used [[phowa]] to transfer his [[own]] [[mindstream]] into [[Kamalaśīla's]] [[body]]. [[Padampa Sangye's]] [[mindstream]] in [[Kamalaśīla's]] [[body]] continued the [[ascent]] to the [[Himalaya]] and thereby transmitted the | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pacification of [[Suffering]] teachings and the [[Indian]] [[form]] of [[Chöd]] which contributed to the [[Mahamudra]] [[Chöd]] of [[Machig Labdrön]]. The [[mindstream]] of [[Kamalaśīla]] was unable to return to his [[own]] [[body]] and so was forced to enter the vacant [[body]] of [[Padampa Sangye]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

=== [[Third Karmapa]]: [[systematizer of Chöd]] === | === [[Third Karmapa]]: [[systematizer of Chöd]] === | ||

| + | |||

[[Chöd]] was a marginal and peripheral [[sādhana]], practiced outside [[traditional]] [[Tibetan Buddhist]] and [[Indian]] [[Tantric]] {{Wiki|institutions}} with a contraindication as caveat of praxis upon all but the most advanced practitioners. Edou foregrounds the textual exclusivity and rarity of the early [[tradition]]. Indeed, due to the itinerant and [[nomadic]] lifestyles of practitioners, they could carry few texts. Hence they were also known as [[kusulu]] or [[kusulupa]]: that is, studying texts rarely whilst focusing on [[meditation]] and praxis: | [[Chöd]] was a marginal and peripheral [[sādhana]], practiced outside [[traditional]] [[Tibetan Buddhist]] and [[Indian]] [[Tantric]] {{Wiki|institutions}} with a contraindication as caveat of praxis upon all but the most advanced practitioners. Edou foregrounds the textual exclusivity and rarity of the early [[tradition]]. Indeed, due to the itinerant and [[nomadic]] lifestyles of practitioners, they could carry few texts. Hence they were also known as [[kusulu]] or [[kusulupa]]: that is, studying texts rarely whilst focusing on [[meditation]] and praxis: | ||

| + | |||

: The nonconventional [[attitude]] of living on the fringe of {{Wiki|society}} kept the [[Chödpas]] aloof from the wealthy [[monastic]] {{Wiki|institutions}} and [[printing]] houses. As a result, the original [[Chöd]] texts and commentaries, often copied by hand, never enjoyed any wide circulation, and many have been lost forever. | : The nonconventional [[attitude]] of living on the fringe of {{Wiki|society}} kept the [[Chödpas]] aloof from the wealthy [[monastic]] {{Wiki|institutions}} and [[printing]] houses. As a result, the original [[Chöd]] texts and commentaries, often copied by hand, never enjoyed any wide circulation, and many have been lost forever. | ||

| − | [[Rangjung Dorje]], [[3rd Karmapa]] [[Lama]], (1284–1339) was a very important systematizer of [[Chöd]] teachings and significantly assisted in their promulgation within the {{Wiki|literary}} and practice [[lineages]] of the [[Kagyu]], [[Nyingma]] and particularly [[Dzogchen]]. It is in this transition from the outer [[charnel ground]] to the {{Wiki|institutions}} of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] that the [[rite]] of the [[Chöd]] becomes more imaginal, an inner practice, that is, the [[charnel ground]] becomes an internal imaginal {{Wiki|environment}}. Schaeffer conveys that the [[Third Karmapa]] was a systematizer of the [[Chöd]] developed by [[Machig Labdrön]] and lists a number of his works on [[Chöd]] consisting of redactions, outlines and commentaries amongst others: | + | |

| + | [[Rangjung Dorje]], [[3rd Karmapa]] [[Lama]], (1284–1339) was a very important systematizer of [[Chöd]] teachings and significantly assisted in their promulgation within the {{Wiki|literary}} and practice [[lineages]] of the [[Kagyu]], [[Nyingma]] and particularly [[Dzogchen]]. It is in this transition from the outer [[charnel ground]] to the {{Wiki|institutions}} of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] that the [[rite]] of the [[Chöd]] becomes | ||

| + | |||

| + | more imaginal, an inner practice, that is, the [[charnel ground]] becomes an internal imaginal {{Wiki|environment}}. Schaeffer conveys that the [[Third Karmapa]] was a systematizer of the [[Chöd]] developed by [[Machig Labdrön]] and lists a number of his works on [[Chöd]] consisting of redactions, outlines and commentaries amongst others: | ||

| + | |||

: [[Rang byung]] was renowned as a systematizer of the [[Gcod]] teachings developed by [[Ma gcig lab sgron]]. His texts on [[Gcod]] include the [[Gcod kyi khrid yig]]; the [[Gcod bka' tshoms chen mo'i sa bcad]] which consists of a topical outline of and commentary on [[Ma gcig lab sgron's Shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa zab mo gcod kyi man ngag gi gzhung bka' tshoms chen mo]] ; the [[Tshogs las yon tan kun 'byung]] ; the lengthy [[Gcod]] kyi [[tshogs]] las rin po che'i phrenb ba 'don bsgrigs bltas chog tu bdod pa [[gcod]] kyi [[lugs]] sor [[bzhag]]; the Ma [[lab sgron]] la gsol ba 'deb pa'i mgur ma; the Zab mo [[bdud]] kyi [[gcod]] yil kyi [[khrid yig]], and finally the [[Gcod]] kyi [[nyams]] len. | : [[Rang byung]] was renowned as a systematizer of the [[Gcod]] teachings developed by [[Ma gcig lab sgron]]. His texts on [[Gcod]] include the [[Gcod kyi khrid yig]]; the [[Gcod bka' tshoms chen mo'i sa bcad]] which consists of a topical outline of and commentary on [[Ma gcig lab sgron's Shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa zab mo gcod kyi man ngag gi gzhung bka' tshoms chen mo]] ; the [[Tshogs las yon tan kun 'byung]] ; the lengthy [[Gcod]] kyi [[tshogs]] las rin po che'i phrenb ba 'don bsgrigs bltas chog tu bdod pa [[gcod]] kyi [[lugs]] sor [[bzhag]]; the Ma [[lab sgron]] la gsol ba 'deb pa'i mgur ma; the Zab mo [[bdud]] kyi [[gcod]] yil kyi [[khrid yig]], and finally the [[Gcod]] kyi [[nyams]] len. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

== Key [[elements]] of the Practice == | == Key [[elements]] of the Practice == | ||

| + | |||

[[Chöd]] literally means "cutting through". It cuts through [[hindrances]] and {{Wiki|obscuration}}, sometimes called '{{Wiki|demons}}' or '[[gods]]'. Examples of {{Wiki|demons}} are [[ignorance]], [[anger]] and, in particular, the [[dualism]] of perceiving the [[self]] as inherently meaningful, contrary to the [[Buddhist doctrine of no-self]]. The [[practitioner]] is fully immersed in the [[ritual]]: "With a stunning array of [[visualizations]], song, {{Wiki|music}}, and [[prayer]], it engages every aspect of one’s being and effects a powerful [[transformation]] of the interior landscape." | [[Chöd]] literally means "cutting through". It cuts through [[hindrances]] and {{Wiki|obscuration}}, sometimes called '{{Wiki|demons}}' or '[[gods]]'. Examples of {{Wiki|demons}} are [[ignorance]], [[anger]] and, in particular, the [[dualism]] of perceiving the [[self]] as inherently meaningful, contrary to the [[Buddhist doctrine of no-self]]. The [[practitioner]] is fully immersed in the [[ritual]]: "With a stunning array of [[visualizations]], song, {{Wiki|music}}, and [[prayer]], it engages every aspect of one’s being and effects a powerful [[transformation]] of the interior landscape." | ||

| + | |||

[[Dzogchen]] [[forms]] of [[Chöd]] enable the [[practitioner]] to maintain [[primordial awareness]] ([[rigpa]]) free from {{Wiki|fear}}. Here, the [[Chöd]] [[ritual]] essentialises [[elements]] of [[phowa]], [[gaṇacakra]], [[pāramitā]] and [[lojong]] [[gyulu]], [[kyil khor]], [[brahmavihāra]], [[ösel]] and [[tonglen]]. | [[Dzogchen]] [[forms]] of [[Chöd]] enable the [[practitioner]] to maintain [[primordial awareness]] ([[rigpa]]) free from {{Wiki|fear}}. Here, the [[Chöd]] [[ritual]] essentialises [[elements]] of [[phowa]], [[gaṇacakra]], [[pāramitā]] and [[lojong]] [[gyulu]], [[kyil khor]], [[brahmavihāra]], [[ösel]] and [[tonglen]]. | ||

| − | [[Chöd]] usually commences with [[phowa]] in which the [[practitioner]] [[visualises]] their [[mindstream]] as the [[five pure lights]] leaving the [[body]] through the aperture of the [[sahasrara]] at the top of the head. This is said to ensure [[psychic]] [[integrity]] of, and [[compassion]] for the [[practitioner]] of the [[rite]] ([[sādhaka]]). In most versions of the [[sādhana]], the [[mindstream]] precipitates into a [[tulpa]] {{Wiki|simulacrum}} of the [[dākinī]] [[Vajrayoginī]]. In the [[body]] of [[enjoyment]] [[attained]] through [[visualization]], the [[sādhaka]] offers the [[ganacakra]] of their [[own]] [[physical body]], to the 'four' guests: [[Triratna]], [[ḍākiṇīs]], [[dharmapalas]], [[beings]] of the [[bhavachakra]], the ever {{Wiki|present}} genius loci and [[pretas]]. The [[rite]] may be protracted with separate [[offerings]] to each [[maṇḍala]] of guests, or significantly abridged. Many variations of the [[sādhana]] still [[exist]]. | + | |

| + | [[Chöd]] usually commences with [[phowa]] in which the [[practitioner]] [[visualises]] their [[mindstream]] as the [[five pure lights]] leaving the [[body]] through the aperture of the [[sahasrara]] at the top of the head. This is said to ensure [[psychic]] [[integrity]] of, and [[compassion]] for the [[practitioner]] of the [[rite]] ([[sādhaka]]). In most versions of the [[sādhana]], the [[mindstream]] precipitates into a [[tulpa]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | {{Wiki|simulacrum}} of the [[dākinī]] [[Vajrayoginī]]. In the [[body]] of [[enjoyment]] [[attained]] through [[visualization]], the [[sādhaka]] offers the [[ganacakra]] of their [[own]] [[physical body]], to the 'four' guests: [[Triratna]], [[ḍākiṇīs]], [[dharmapalas]], [[beings]] of the [[bhavachakra]], the ever {{Wiki|present}} genius loci and [[pretas]]. The [[rite]] may be protracted with separate [[offerings]] to each [[maṇḍala]] of guests, or significantly abridged. Many variations of the [[sādhana]] still [[exist]]. | ||

| + | |||

[[Chöd]], like all [[tantric]] systems, has outer, inner and secret aspects. They are described in an {{Wiki|evocation}} sung to [[Nyam Paldabum]] by [[Milarepa]]: | [[Chöd]], like all [[tantric]] systems, has outer, inner and secret aspects. They are described in an {{Wiki|evocation}} sung to [[Nyam Paldabum]] by [[Milarepa]]: | ||

| + | |||

: External [[chod]] is to wander in {{Wiki|fearful}} places where there are [[deities]] and {{Wiki|demons}}. Internal [[chod]] is to offer one's [[own]] [[body]] as [[food]] to the [[deities]] and {{Wiki|demons}}. [[Ultimate]] [[chod]] is to realize the [[true nature]] of the [[mind]] and cut through the fine strand of [[hair]] of {{Wiki|subtle}} [[ignorance]]. I am the [[yogi]] who has these three kinds of [[chod]] practice. | : External [[chod]] is to wander in {{Wiki|fearful}} places where there are [[deities]] and {{Wiki|demons}}. Internal [[chod]] is to offer one's [[own]] [[body]] as [[food]] to the [[deities]] and {{Wiki|demons}}. [[Ultimate]] [[chod]] is to realize the [[true nature]] of the [[mind]] and cut through the fine strand of [[hair]] of {{Wiki|subtle}} [[ignorance]]. I am the [[yogi]] who has these three kinds of [[chod]] practice. | ||

| + | |||

The [[Chöd]] is now a staple of the advanced [[sādhana]] of [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[traditions]]. It is practiced worldwide following dissemination by the [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|diaspora}}. | The [[Chöd]] is now a staple of the advanced [[sādhana]] of [[Tibetan Buddhist]] [[traditions]]. It is practiced worldwide following dissemination by the [[Tibetan]] {{Wiki|diaspora}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

== {{Wiki|Western}} reports on [[Chöd]] practices == | == {{Wiki|Western}} reports on [[Chöd]] practices == | ||

| − | [[Chöd]] was mostly practised outside the [[Tibetan]] [[monastery]] system by [[chödpas]], who were [[yogis]], yogiṇīs and [[ngagpas]] rather than [[bhikṣus]] and [[bhikṣuṇīs]]. Because of this, material on [[Chöd]] has been less widely available to {{Wiki|Western}} readers than some other [[tantric]] [[Buddhist practices]]. The first {{Wiki|Western}} reports of [[Chöd]] came from a {{Wiki|French}} adventurer who lived in [[Tibet]], {{Wiki|Alexandra David-Néel}} in her travelogue [[Magic]] and {{Wiki|Mystery}} in [[Tibet]], published in 1932. Walter {{Wiki|Evans-Wentz}} published the first translation of a [[Chöd]] liturgy in his 1935 [[book]] [[Tibetan]] [[Yoga]] and Secret [[Doctrines]]. [[Anila Rinchen]] [[Palmo]] translated several {{Wiki|essays}} about [[Chöd]] in the 1987 collection Cutting Through [[Ego-Clinging]]. Giacomella Orofino's piece entitled "The [[Great Wisdom]] Mother" was included in [[Tantra]] in Practice in 2000 and in addition she published articles on [[Machig Labdrön]] in {{Wiki|Italian}}. | + | |

| + | [[Chöd]] was mostly practised outside the [[Tibetan]] [[monastery]] system by [[chödpas]], who were [[yogis]], yogiṇīs and [[ngagpas]] rather than [[bhikṣus]] and [[bhikṣuṇīs]]. Because of this, material on [[Chöd]] has been less widely available to {{Wiki|Western}} readers than some other | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[tantric]] [[Buddhist practices]]. The first {{Wiki|Western}} reports of [[Chöd]] came from a {{Wiki|French}} adventurer who lived in [[Tibet]], {{Wiki|Alexandra David-Néel}} in her travelogue [[Magic]] and {{Wiki|Mystery}} in [[Tibet]], published in 1932. Walter {{Wiki|Evans-Wentz}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | published the first translation of a [[Chöd]] liturgy in his 1935 [[book]] [[Tibetan]] [[Yoga]] and Secret [[Doctrines]]. [[Anila Rinchen]] [[Palmo]] translated several {{Wiki|essays}} about [[Chöd]] in the 1987 collection Cutting Through [[Ego-Clinging]]. Giacomella Orofino's piece entitled "The [[Great Wisdom]] Mother" was included in [[Tantra]] in Practice in 2000 and in addition she published articles on [[Machig Labdrön]] in {{Wiki|Italian}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

{{W}} | {{W}} | ||

| − | |||

[[Category:Tantric practices]] | [[Category:Tantric practices]] | ||

{{TibetanTerminology}} | {{TibetanTerminology}} | ||

[[Category:Tibetan Buddhist practices]] | [[Category:Tibetan Buddhist practices]] | ||

[[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | [[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Chöd]] | [[Category:Chöd]] | ||

Latest revision as of 09:54, 30 November 2023

Chöd (Tibetan: གཅོད, Wylie: gcod lit. 'to sever'), is a spiritual practice found primarily in Tibetan Buddhism. Also known as "Cutting Through the Ego," the practice is based on the Prajñāpāramitā sutra. It combines prajñapāramitā philosophy with specific meditation methods and a tantric ritual.

Nomenclature, orthography and etymology

(Tibetan: གཅོད་སྒྲུབ་ཐབས་ gcod sgrub thabs; Sanskrit: छेद साधना cheda-sādhana; both literally "cutting practice"), pronounced chö (the d is silent).

Indian Antecedents

- “...Chöd was never a unique, monolithic tradition. One should really speak of Chöd traditions and lineages since Chöd has never constituted a school.”

A form of Chöd was practiced in India by Buddhist mahāsiddhas, prior to the 10th Century. However, Chöd as practiced today developed from the entwined traditions of the early Indian tantric practices transmitted to Tibet and the Bonpo and Tibetan Buddhist Vajrayāna lineages. Besides the Bonpo, there are two main Tibetan Buddhist Chöd

traditions, the "Mother" and "Father" lineages. In Tibetan tradition, Dampa Sangye is known as the Father of Chöd and Machig Labdron, founder of the Mahāmudra Chöd lineages, as the Mother of Chöd. Chöd developed outside the monastic system. It was subsequently adopted by the four main schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

The Chöd, as an internalization of an outer ritual, involves a form of self-sacrifice: the practitioner visualizes their own body as the offering at a ganachakra or tantric feast. The purpose of the practice is to engender a sense of victory and fearlessness. These two qualities are represented iconographically by the dhvaja, or victory banner and the kartika, or

ritual knife. The banner symbolizes overcoming obstacles and the knife symbolizes cutting through the ego. Since fearful or painful situations help the practitioner's work of cutting through attachment to the self, such situations may be cultivated. Machig Labdrön said: "To consider adversity as a friend is the instruction of Chöd".

Sarat Chandra Das equated the Chöd practitioner (Tibetan: གཅོད་པ, Wylie: chod pa) with avadhūta:

- "ཀུ་སུ་ལུ་པ ku-su-lu-pa ¿ is a word of Tantrik mysticism, its proper Tibetan equivalent being གཅོད་པ gcod-pa, the art of exorcism. The mystic Tantrik rites of the Avadhauts, called Avadhūtipa in Tibet, exist in India."

NB: ¿ = kusulu or kusulupa (Sanskrit; Tibetan loanword) that is studying texts rarely whilst focusing on meditation and praxis. Often used disparagingly by pandits.

Avadhūtas, or 'mad saints,' are well known for their 'crazy wisdom.' Chöd practitioners (chödpas) are a type of avadhūta particularly respected, detested, feared or held in awe due to their role as denizens of the charnel ground. Edou says they were often associated with the role of shaman and exorcist:

- "The Chödpa's very lifestyle on the fringe of society - dwelling in the solitude of burial grounds and haunted places, added to the mad behavior and contact with the world of darkness and mystery - was enough for credulous people to view the Chödpa in a role usually attributed to shamans and other exorcists, an assimilation which also happened to medieval European shepherds. Only someone who has visited one of Tibet's charnel fields and witnessed the offering of a corpse to the vultures may be able to understand the full impact of what the Chöd tradition refers to as places that inspire terror.

Iconography

In Chöd, the adept symbolically offers the flesh of their body in a form of gaṇacakra or tantric feast. Iconographically, the skin of the practitioner's body may represent surface reality or maya. It is cut from bones that represent the true reality of the mindstream. Some commentators see the Chöd ritual as cognate with the prototypical initiation of a shaman. Traditionally, Chöd is regarded as challenging, potentially dangerous and inappropriate for some practitioners.

Ritual objects

Practitioners of the Chöd ritual, Chödpa, use a kangling or human thighbone trumpet, and a Chöd drum, a hand drum similar to but larger than the ḍamaru commonly used in Tibetan ritual. In a version of the Chöd sādhana of Jigme Lingpa from the Longchen Nyingthig terma, five ritual knives (phurbas), are employed to demarcate the maṇḍala of the offering and to affix the five wisdoms.

Key to the iconography of Chöd is the hooked knife or skin flail (kartika). A flail is an agricultural tool used for threshing to separate grains from their husks. Similarly, the kartika symbolically separates the body mind from the mindstream. The kartika imagery in the Chöd ritual provides the practitioner with an opportunity to realize Buddhist doctrine:

- The Kartika (Skt.) or curved knife symbolizes the cutting of conventional wisdom by the ultimate insight into emptiness. It is usually present as a pair, together with the skullcup, filled with wisdom nectar. On a more simple level, the skull is a reminder of (our) impermanence. Between the knife and the handle is a makara-head, a mythical monster.

Bone ornaments

A recurrent theme in the iconography of the Tibetan Buddhist tantras is a group of five or six bone ornaments ornamenting the bodies of various enlightened beings who appear in the texts. The Sanskrit includes the term mudrā, meaning "seal". The Hevajra tantra associates the bone ornaments directly with the five wisdoms, which also appear as the Five Dhyani Buddhas. These are explained in a commentary to the Hevajra tantra by Jamgön Kongtrul:

- the wheel-like crown ornament (sometimes called "crown jewel"), symbolic of Akṣobhya and mirror-like pristine awareness

- the earrings representing Amitābha and the pristine awareness of discernment

- the necklace symbolizing Ratnasambhāva and the pristine awareness of total sameness

- the bracelets and anklets symbolic of Vairocāna and the pristine awareness of the ultimate dimension of phenomena

- the girdle symbolizing Amoghasiddhi and the accomplishing pristine awareness

- The sixth ornament sometimes referred to is ash from a cremation ground smeared on the body.

Origins of the practice

Sources such as Stephen Beyer have described Machig Labdrön as the founder of the practice of Chöd. This is accurate in that she is the founder of the Tibetan Buddhist Mahamudrā Chöd lineages. Machig Labdrön is credited with providing the name "Chöd" and

developing unique approaches to the practice. Biographies suggest it was transmitted to her via sources of the mahāsiddha and Tantric traditions. She did not found the Dzogchen lineages, although they do recognize her, and she does not appear at all in the Bön Chöd lineages. Among the formative influences on Mahamudrā Chöd was Dampa Sangye's 'Pacification of Suffering'.

The transmission of Chöd to Tibet

There are several hagiographic accounts of how Chöd came to Tibet. One spiritual biography asserts that shortly after Kamalaśīla won his famous debate with Moheyan as to whether Tibet should adopt the "sudden" route to

enlightenment or his "gradual" route, Kamalaśīla used the technique of phowa, transferring his mindstream to animate a corpse polluted with contagion in order to safely move the hazard it presented. As the mindstream of Kamalaśīla was otherwise engaged, a

mahasiddha by the name of Padampa Sangye came across the vacant "physical basis" of Kamalaśīla. Padampa Sangye, was not karmically blessed with an aesthetic corporeal form, and upon finding the very handsome and healthy empty body of

Kamalaśīla, which he assumed to be a newly dead fresh corpse, used phowa to transfer his own mindstream into Kamalaśīla's body. Padampa Sangye's mindstream in Kamalaśīla's body continued the ascent to the Himalaya and thereby transmitted the

Pacification of Suffering teachings and the Indian form of Chöd which contributed to the Mahamudra Chöd of Machig Labdrön. The mindstream of Kamalaśīla was unable to return to his own body and so was forced to enter the vacant body of Padampa Sangye.

Third Karmapa: systematizer of Chöd

Chöd was a marginal and peripheral sādhana, practiced outside traditional Tibetan Buddhist and Indian Tantric institutions with a contraindication as caveat of praxis upon all but the most advanced practitioners. Edou foregrounds the textual exclusivity and rarity of the early tradition. Indeed, due to the itinerant and nomadic lifestyles of practitioners, they could carry few texts. Hence they were also known as kusulu or kusulupa: that is, studying texts rarely whilst focusing on meditation and praxis:

- The nonconventional attitude of living on the fringe of society kept the Chödpas aloof from the wealthy monastic institutions and printing houses. As a result, the original Chöd texts and commentaries, often copied by hand, never enjoyed any wide circulation, and many have been lost forever.

Rangjung Dorje, 3rd Karmapa Lama, (1284–1339) was a very important systematizer of Chöd teachings and significantly assisted in their promulgation within the literary and practice lineages of the Kagyu, Nyingma and particularly Dzogchen. It is in this transition from the outer charnel ground to the institutions of Tibetan Buddhism that the rite of the Chöd becomes

more imaginal, an inner practice, that is, the charnel ground becomes an internal imaginal environment. Schaeffer conveys that the Third Karmapa was a systematizer of the Chöd developed by Machig Labdrön and lists a number of his works on Chöd consisting of redactions, outlines and commentaries amongst others:

- Rang byung was renowned as a systematizer of the Gcod teachings developed by Ma gcig lab sgron. His texts on Gcod include the Gcod kyi khrid yig; the Gcod bka' tshoms chen mo'i sa bcad which consists of a topical outline of and commentary on Ma gcig lab sgron's Shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa zab mo gcod kyi man ngag gi gzhung bka' tshoms chen mo ; the Tshogs las yon tan kun 'byung ; the lengthy Gcod kyi tshogs las rin po che'i phrenb ba 'don bsgrigs bltas chog tu bdod pa gcod kyi lugs sor bzhag; the Ma lab sgron la gsol ba 'deb pa'i mgur ma; the Zab mo bdud kyi gcod yil kyi khrid yig, and finally the Gcod kyi nyams len.

Key elements of the Practice

Chöd literally means "cutting through". It cuts through hindrances and obscuration, sometimes called 'demons' or 'gods'. Examples of demons are ignorance, anger and, in particular, the dualism of perceiving the self as inherently meaningful, contrary to the Buddhist doctrine of no-self. The practitioner is fully immersed in the ritual: "With a stunning array of visualizations, song, music, and prayer, it engages every aspect of one’s being and effects a powerful transformation of the interior landscape."

Dzogchen forms of Chöd enable the practitioner to maintain primordial awareness (rigpa) free from fear. Here, the Chöd ritual essentialises elements of phowa, gaṇacakra, pāramitā and lojong gyulu, kyil khor, brahmavihāra, ösel and tonglen.

Chöd usually commences with phowa in which the practitioner visualises their mindstream as the five pure lights leaving the body through the aperture of the sahasrara at the top of the head. This is said to ensure psychic integrity of, and compassion for the practitioner of the rite (sādhaka). In most versions of the sādhana, the mindstream precipitates into a tulpa

simulacrum of the dākinī Vajrayoginī. In the body of enjoyment attained through visualization, the sādhaka offers the ganacakra of their own physical body, to the 'four' guests: Triratna, ḍākiṇīs, dharmapalas, beings of the bhavachakra, the ever present genius loci and pretas. The rite may be protracted with separate offerings to each maṇḍala of guests, or significantly abridged. Many variations of the sādhana still exist.

Chöd, like all tantric systems, has outer, inner and secret aspects. They are described in an evocation sung to Nyam Paldabum by Milarepa:

- External chod is to wander in fearful places where there are deities and demons. Internal chod is to offer one's own body as food to the deities and demons. Ultimate chod is to realize the true nature of the mind and cut through the fine strand of hair of subtle ignorance. I am the yogi who has these three kinds of chod practice.

The Chöd is now a staple of the advanced sādhana of Tibetan Buddhist traditions. It is practiced worldwide following dissemination by the Tibetan diaspora.

Western reports on Chöd practices

Chöd was mostly practised outside the Tibetan monastery system by chödpas, who were yogis, yogiṇīs and ngagpas rather than bhikṣus and bhikṣuṇīs. Because of this, material on Chöd has been less widely available to Western readers than some other

tantric Buddhist practices. The first Western reports of Chöd came from a French adventurer who lived in Tibet, Alexandra David-Néel in her travelogue Magic and Mystery in Tibet, published in 1932. Walter Evans-Wentz

published the first translation of a Chöd liturgy in his 1935 book Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrines. Anila Rinchen Palmo translated several essays about Chöd in the 1987 collection Cutting Through Ego-Clinging. Giacomella Orofino's piece entitled "The Great Wisdom Mother" was included in Tantra in Practice in 2000 and in addition she published articles on Machig Labdrön in Italian.