Mahayana by Arnie Kozak, Ph.D.

Mahayana Buddhism is the vehicle most familiar to Americans in the form of Zen. Mahayana has been around since the Second Council, but Mahayana can also argue a direct descent to the Buddha's teachings. Mahayana Buddhists believe they split off from the Theravada tradition in order to reform the teachings and take them back to a purer form the Buddha had originally taught, although the Mahayana sutras such as the Perfection of Wisdom and Heart Sutra are not directly attributed to the Buddha.

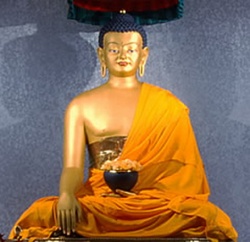

Manjushri is the bodhisattva of wisdom — he symbolizes the wisdom one needs in order to seek the truth. In artworks depicting Manjushri, he is often portrayed with one hand holding a sword, which is needed to cut through illusion to the heart of wisdom. In the other hand he holds the sacred text of wisdom, the Prajna-Paramita Sutra.

If you think Buddhism lacks prophecies, think again. Buddhist scholar Mark Blum describes the Mahayana belief in the “Period of the Final Law.” This period of dark decline for humanity (know, as mofa in Chinese and mappo in Japanese) had come about somewhere between the sixth and eleventh centuries because too much time had elapsed since the death of the Buddha, and fewer and fewer people understood his teaching. “This final period could last up to ten thousand years and all sorts of dire consequences were described, such as increased corruption, conflict, and even a shortening of human life. But the end of this age was unambiguously marked by the advent of a new buddha Maitreya, who will usher in a new era of peace and enlightenment.” Emptiness

The cardinal emphasis of Mahayana is on shunyata, often translated as “emptiness” or “the void.” The Buddha's early teachings discuss the emptiness of self (anatman, anatta) and in the Mahayana this concept is expanded to everything.

Shunyata is, perhaps, the most confusing and mystical of the Buddhist concepts and the most difficult for the Western mind to grasp. Truth goes beyond dualistic distinctions and thus “emptiness is form” and “form is emptiness.” Huh? This is a departure from the earlier concepts presented in the Abhidharma that did not hold to this notion of emptiness.

These distinctions can get you bogged down in subtle philosophical arguments. Is the world real? And what does it mean to be real? To further clarify things (or complicate things), things can be seen as conventionally real, but there is an ultimate reality that underlies what is perceived. Confused yet?

In Mahayana tradition, when one wakes up one realizes that the whole world is emptiness, that emptiness is not just the self but all things, and form and emptiness are the same thing, indistinguishable from one another. Or as stated in the Heart Sutra: “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form.” It is hard to grasp this conceptually. The best way is to practice meditation and experience it for yourself.

Like the self, everything has the quality of space and energy and change. Further Explanations

Stephen Batchelor tries to cut through this confusion by going back to basics. According to Bachelor, the Buddha's original teachings did not make these distinctions between relative and ultimate reality (which themselves are at risk for creating a duality). Things are constantly changing, he taught, and he cautioned his followers not to cling to anything. Everything that occurs does so in dependence upon something else (the doctrine of dependent origination).

But is there really a duality here? Conventional reality is necessary so that you know your name and know how to find your way home. Ultimate reality refers to something else. When you meditate you will experience these conventional things in a different way — this is where language breaks down — such that some deeper or more ultimate sense of things will be experienced. Reaching Enlightenment

It's hard to describe in language and has to be experienced for yourself. When all these concepts cease to function, you have reached enlightenment. When you go beyond dualistic categories such as self and world, you are liberated. This is what all Buddhists strive for. The aim is to get beyond all your preconceived notions of reality, including those about yourself. Beware! You can become attached to the concept of emptiness itself, and through the back door you will once again be trapped in the world of concepts and miss out on liberation. Don't worry though. Of course in the next moment you'll have another chance!

Vipassana practice plays a more central role in the Theravada than in the Mahayana where vipashyana (Sanskrit for vipassana; Mahayana sutras were written in Sanskrit and they therefore use the Sanskrit version of terms over the Pali. That is, dharma instead of dhamma, nirvana instead of nibbana) is combined with elaborate imagery, chanting, and other practices that developed in the centuries after the Buddha. In the Mahayana, prajna (wisdom) may be represented by Manjushri, who yields a sword that cuts through delusion and desire. Ox-Herding Pictures

The Mahayana Path is captured in the traditional sequence of painting in the Chan and Zen traditions. The ox, an animal sacred in India, represents buddha-nature, and the boy in the illustrations represents the self.

“Seeking the Ox.” Here you are lost in samsara, but having been exposed to the teaching of the Buddha, you are pulled towards a higher truth.

“Finding the Tracks.” Here you engage with listening to teachings and finding the path.

“First Glimpse of the Ox.” Meditation practice provides the vehicle to start realizing a taste of prajna (wisdom).

“Catching the Ox.” Comes when you have a deeper grasping of the kleshas or three poisons (greed, hatred, and delusion), and the limitations that come with regarding the self as a solid object worthy of protection (anatta).

“Taming the Ox.” This occurs when you start to have peeks at the peak experience of satori.

“Riding the Ox Home.” When you have a complete experience of satori.

“Both Ox and Self Forgotten.” This comes when you can now experience life with the freedom that satori provides.

“Both Ox and Self Forgotten.” Here you go beyond even the concepts of dharma and the tradition you studied within. The Buddha likened this to the raft that carries you across the river of samsara, once you've reached the other side you don't keep carrying the raft.

“Returning to the Source.” From this place you realize that the entire natural world is the embodiment of enlightenment.

“Entering the market with Helping Hands.” This makes the bodhisattva path explicit. Having gotten to this place you now work for the betterment of everyone else.