The Education System of Three Major Monasteries in Lhasa

I.The Education System of Monasteries Under the Yellow Sect of Lamaism

The rise of the Yellow Sect (or the dGe-lugs-pa Secti[1]) in Tibet in the 15th century was closely related to its mature system of monasteries and sound organization of personnel.

In the 13th and 14th centuries, previously thriving sects of Tibetan Buddhism, such as the Sa-skya-pa Sect[2] and the bKav-brgyud-pa Sect[3], gradually declined one after another. To exploit Tibetan Buddhism, both the Yuan and Ming Dynasties adopted favorable policies towards it. Thus almost all higher-ranking monks of the two sects focused on seeking power and their own interests, and their private lives became increasingly extravagant and corrupt. As a result, they alienated themselves farther and farther from the general population. In addition, the aristocratic clans took advantage of such loose organization of the monks and the monasteries, by infiltrating them and turning them into their private estates. For instance, the head of the Sa-skya-pa Sect was passed on from generation to generation within a clan. In other words, the monasteries of the Sa-skya-pa Sect were private temples for this clan. It was with the political and military support from the Court of the Yuan Dynasty that this clan achieved and maintained its ruling position. Though the bKavbrgyud-pa Sect did not rely on the central government as much as the Sa-skya-pa Sect, and was full of vitality for a time, it finally also fell into the hands of powerful clans[4]. As these religious sects set up a separatist regime by force of arms and their branches also fought against each other, Tibetan society entered a period of turbulence and suffering. In consequence, Tsong-kha-pa, the founder of the Yellow Sect, started his religious reforms. First, monasteries were required to rely on their own efforts rather than support from the Central Government. Second, to prevent powerful clans from taking over the management of monasteries, monks were strictly required to obey regulations and taboos. For example, monks were forbidden to marry so that they were clearly distinguished from laymen. Thus, no ambitious laymen were able to enter the society of monks to seize the property of monasteries of to have their positions inherited by their offspring or relatives. The Yellow Sect stipulated that monastery property should belong to the monastic order as a whole and democratized the administration of monasteries in an attempt to move monasteries closer to the grassroots. To promote social cohesion among monks of various classes, this sect established a monastic management system that allowed every monk, no matter what family background he had, wealthy or poor, influential or humble, to be promoted step by step in rank and enter the leadership of the monastery according to his talent and capability.

Owing to such measures adopted at an early stage, the Yellow Sect effectively removed the destructive forces both inside and outside of its organization, reformed the monastic management system and greatly enlarged their influence throughout monasticism in general. Therefore, monasteries of the Yellow Sect became a new force in Tibetan society. In contrast to other sects controlled by aristocratic clans, these monasteries won the broad support of Tibetans. After Tsong-kha-pa established the dGav-ldan Monastery, the first monastery of the Yellow Sect, the vBras-spungs, Se-ra, and bKra-shis-lhun-po Monasteries were collectively called the〝Four Major Monasteries of the Yellow Hat Sect〞[5], and laid a foundation for its success. When Both the Dalai Lama system in the vBras-spungs Monastery and Panchen Lama system in the bKra-shis-lhun-po Monastery were established and the two Lamas achieved political power, the organization of the Yellow Hat Sect was further perfected and its influence finally expanded into Xikang (Khams,) Sichuan, Yunan, Qinghai, Gansu, Mongolia, and Siberia. Up to the present day, the number of branch monasteries derived from these four major institutions is uncountable. For these reasons, the Yellow Hat Sect is considered the most important school of Tibetan Lamaism.

The core of the four major monasteries as well as all other monasteries of the Yellow Hat Sect was a complete educational system. At the same time, these four monasteries were the highest educational institutions for all monks (including Rin-po-ches) of this sect. With this system, the four monasteries effectively united all Yellow Hat Sect monasteries under a collective leadership. Therefore, it had on conflict among its internal branches as other sects did. All Rin-po-ches, eminent monks and scholars of this sect had to study in the four monasteries before they established their religious and social positions. Meanwhile, those monks who had studied and achieved degrees in four monasteries would receive more respect in areas under the Yellow Sect’s influence. Among the four, the dGav-ldan, vBras-spung, Se-ra Monasteries were under the Dalai Lama system and constituted the renowned〝three major monasteries in Lhasa〞. These three shared the same education system while the bKra-shis-lhun-po Monastery had a parallel system as it was under the Panchen system. This division was only based on an administrative hierarchical relationship. As a matter of fact, the two educational systems had no basic difference in terms of content and principle, except for distinctions in names and other minor details. By understanding the educational system of three major institutions in Lhasa, we can also know that of the bKra-shis-lhun-po Monastery. This paper will therefore only describe the system of the three major institutions.

II. dPe-cha-bas in the Three Major Monasteries in Lhasa

The three monasteries had a large number of monks and each was almost the size of a small town. The monks fell under various classifications that frequently changed. In addition, they varied greatly in age, property, and social status. In spite of the complication of their origin and background, the monks could be classified into four categories in a broad sense:

(1) Monastic administrative group. This was a big organization, including those in charge of administration, justices, executive departments, monastic property, fiefdoms, cash (funds), business and procurement. It is necessary to point out that most of these posts had a fixed term and they were probably part-time jobs for the post-holders. The three monasteries were large. They owned a great deal of agricultural land, pasture, real estate, and branch monasteries as well as having many believers. Therefore, the whole organization was very complicated and some posts, for example management of finances, business and procurement required professional expertise. Thus many monks stayed in these posts all their lives and formed a distinct group.

(2) Monks who came to the three monasteries to get professional training in particular religious fields; for instance, how to chant sutras and incantations and how to preside over various religious rites. These monks not only took positions in religious activities in monasteries, but also went out to hold religious rites for Buddhist believers, including praying for happiness, warding off disasters, hearing deathbed confessions, expiating of the sins of the dead, divining and so on.

(3) Monk artisans and those who did manual labor. The former took jobs such as copying, drawing, sculpting, carving wood blocks for printing (though part-time in most cases); the majority of the latter type was illiterate. They were either forced by others to do unpaid service or took the position of〝military monks〞 to maintain security and order in the monasteries.

(4) Student monks called dPe-cha-ba[6] in Tibetan, literally ‘scholars’. They studied courses according to an established curriculum, and were promoted grade by grade until they passed all examinations and received the highest degree.

It is necessary to point out that there was no clear-cut boundary between these four categories of monks. For example, the most important administrators of the monasteries were dPe-cha-bas with an academic degree, and secondary administrators were often monks who had been dPe-cha-bas for several years. In addition, it was possible for a non-dPe-cha-ba to become a dPe-cha-ba and vice versa. However, the monks can still be basically classified into these four groups according to the characteristics of their daily life and practice. Among the four, the percentage of dPe-cha-ba was the lowest, probably less than one quarter of the total population in each monastery.

In a broad sense, every monk learned sutras and conducted Buddhist practice after they entered the monastery. However, dPe-cha-bas of the three monasteries had to study under a more complete and intensive education system beyond hair shaving, receiving ordination and doing routine work like other monks. This system established a learning procedure for dPe-cha-bas- they must begin with Sutras(which stress Buddhist doctrines and philosophy) and then study Tantras (which emphasize practice).When studying Sutra, they were required to take formal logic first as this course would teach them methods of thinking and debating. This teaching mode was borrowed from Indian Buddhism, which had adopted it much earlier to train their monks to gain a better understanding of Buddhist doctrines. In the Tibetan language, this teaching mode, which stresses debating on Buddhist scriptures, is called mTshan-nyid.[7] Attaching importance to debating in teaching was one of the main characteristics that distinguished the monasteries of the Yellow Hat Sect from other Buddhist sects.

The abbots of the three monasteries and the other monasteries of the Yellow Hat Sect could only be selected from dPe-cha-bas who had gained an academic degree according to the above procedure. In addition, nobody but dPe-cha-bas with an academic degree had the opportunity to step on to the political stage[8] and become a leading figure. It was only dPe-cha-bas of this sort who were permitted to be promoted to the religious circle and eventually enter into the class of reincarnated Rin-po-ches. In consequence, all Rin-po-ches of the Yellow Hat Sect were dPe-cha-bas who had received the same type of training, which laid a solid foundation for their religious, political and social status. This is why we that dPe-cha-bas, as an educated group in the monasteries of the Yellow Sect, were the backbone of the monastic organization of this sect.

[[File:080mchod-khang_(Sutra_Hall)_in_the_Drepung_Monastery.jpg|thumb|300px|Decoration of the mchod-khang (Sutra Hall) in the Drepung Monastery)]

III. Types of dPe-cha-bas and Their Status in the Monasteries

Each of the vBras-spungs, Se-ra and dGav-ldan monasteries consisted of several independent components called Grwa-tshang,[9] which were like colleges in modern universities. Each Grwa-tshang included many Khams-tshans, which were similar to dormitories with roommates basically all coming from the same ares.[10] All activities in the three monasteries, including the education of dPe-cha-bas, were based on the three levels of institution, namely, monastery, Grwa-tshang and Khams-tshan. Among the three, Grwa-tshang was the most important.

The education of dPe-cha-bas was within the mKhan-po’s[11] responsibilities in Grwa-tshangs. The mKhan-po was the administrative head of a Grwa-tshang and comparable to the principal of a college. The other administrative personnel, including dBu-mdzad, gZhung-las-pa and dGe-skos,[12] helped him deal with administrative and teaching affairs (mostly the latter) in Grwa-rshangs. dBu-mdzad was the leading chanter in important chanting ceremonies. gZhung-las-pa was responsible for supervising and encouraging dPe-cha-bas to debate. The role of dGe-sKos was to help the mKhan-po manage the education of dPe-cha-bas and to test them. They were also responsible for the register of monk names, monks’ conduct and public order. The three positions altogether were called dBu-chos-gsum, meaning three heads in charge of learning sutras. Along with the mKham-po, they composed the leadership of teaching departments in the Grwa-tshangs.

The three monasteries had no restrictions over the entrance of ordinary monks and dPe-cha-bas. In principle, any man believing in Buddhism, no matter what his race, ethnic identity, education level, wealth or social status, could apply to enter the monasteries when they were over six or seven years of age. But an applicant was required to invite a monk who had been in the monastery for several years to guarantee that this applicant would conduct himself properly and obey all the monastic regulations. As a result, the dPe-cha-bas, when they first entered into the monasteries, had different education levels. Some were very knowledgeable about Buddhist scriptures; some only had preliminary knowledge; still others were totally illiterate. Grwa-tshang would place all new dPe-cha-bas into a preparatory class named bsDus-grwa, [13] regardless of their education level and age.

Grwa-tshangs would not provide dPe-cha-bas with teachers but they had a number of rights that will be described in the following. Every dPe-cha-ba had to find a tutor on his own, and he could apprentice to several tutors at the same time if he wished and had enough money. The tutors were often senior monks with an academic degree in the monasteries. The wealthy and influential monks were able to apprentice to the most eminent lamas while poor ones could only learn from lamas with less renown.

Grwa-tshangs never tested the student monks in the bsDus-grwa class. Whether they should enter into regular classes or not was completely dependent upon the suggestion of a student’s individual tutor. Since the monks in the class varied greatly in educational level, some of them could enter regular classes after a few months while some had to wait several years, as they had to start from the very beginning.

The three monasteries were slightly different in dPe-cha-bas’ grading and learning procedure. For example, the vBras-Spungs Monastery had I5 grades, the Se-ra I2 and the dGav-Idan[14] I3. They also varied in the name of these grades and the number of years required by each one. Some grades required a year; some two years and some had no time restriction-for example, the highest grade. All three monasteries called the highest grade vDzin-dang-po.[15] All dPe-cha-bas who had finished all grades except for the highest would be placed into the vDzin-dang-po. They could stay in this grade for a long time until they achieved an academic degree or left the monastery.

It would take an illiterate 20-25 years to receive an academic degree after his entry into any of the three monasteries. This procedure was similar to a modern education process from kindergarten to university.

However, this situation was only applicable to ordinary dPe-cha-bas. For the wealthy or those with Rin-po-che status, they could apply for and receive a preferential qualification named dMigs-bsal[16] after a certain procedure. With this qualification, they not only enjoyed many privileges in daily life, but were also allowed to reduce their length of study by five to six years or more.

As already mentioned, all affairs of the three monasteries wire carried out according to the three administrative levels, namely, monastery, Grwa-tshang, and Khams-tshan. As soon as a monk (including a dPe-cha-ba) entered any of the three monasteries, he would immediately have a clear relationship with the three levels in terms of rights and duties. Specifically, he had the right to receive a certain ration of subsidies in kind or money while his duties would involve doing unpaid work for the three levels and serving a fixed or temporary corvee. As this work and corvee would take much time, dPe-cha-bas would generally like to achieve the qualification of dMigs-bsal when they had enough money to do so, in order that they could be free from the work and labor. This was especially true of Rin-po-ches with higher social status.

[[File:08Loseling_Dratsang_(blo-gas_gling_grwa-tshang)_of_the_Drepung.jpg|thumb|300px|Loseling Dratsang (blo-gas gling grwa-tshang) of the Drepung Monastery)]

A monk could apply for dMigs-bsal according to his social status and financial capability at the three levels of the monastery, Grwa-tshang and Khams-tshan, as he had rights and duties at the three levels. dMigs-bsal could be classified into two types: one was sPrul-sKu[17] only offered to monks who were Rin-po-ches; the other was chos-mdzad,[18] which could be applied for by all monks with enough financial resources. Sprul-sKu and chos-mdzad could be further classified into several types at the three administrative levels.

First was Tshogs-chen sPrul-sKu.[19] Any Rin-po-ches with high status could apply for it to Dalai Lamas or Agents. Having been approved, they would give tea and alms to all monks in the Tshogs-chen Hall of the monastery. Then he would give tea and alms again in the Grwa-tshang and the Grand Hall of his Khams-tshan. After the three rites, they would officially receive the qualification of Tshogs-chen sPrul-sKu at monastery level and were free from all labor service in the monastery.

Second was Grwa-tshang sPrul-sKu. Rin-po-ches of secondary importance could apply for it to the mKhan-po or their committees of Grwa-tshang. After the application was approved, they would give tea and alms to all monks in the Grand Hall of his Grwa-tshang and in the Grand Hall of his Khams-tshan. Then they officially received the qualification of Grwa-tshang sPrul-SKu and were free from all labor service in the monastery. As all Rin-po-ches were financially quite well off, the favorable conditions for sPrul-sKu were not provided at the level of Khams-tshan but at the two levels of Tshogs-chen and Grwa-tshang. The wealthy monks who were not Rin-po-ches could get the status of chos-mdzad at the levels of Tshogs-chen, Grwa-tshang and Khams-tshan through the same procedure. However, Khams-tshan chos-mdzad was not free from the labor service at monastery level but rather at the level of Grawa-tshang.

As mentioned, the monastery authorities not only allowed dPe-cha-bas with the qualification of dMigs-bsal to be exempted from labor service, but also allowed them privilege of receiving their academic degree and graduating earlier than usual. The justification of the monastery authorities was: since dPe-cha-bas with the qualification of dMigs-bsal need not spend time on various labor services, they had more time for study, which enabled them study at a faster pace and thus shorten the number of years required.

IV. Courses and Teaching Methods

The basic teaching mode of the three monasteries was self-study and private instruction, but there was a general requirement for dPe-cha-bas’ courses, that is, they could graduate before finishing Five Great Treaties; Explanation of the Touchstones, Ornament of Clear Realization, Entrance to the doctrine of the Mean, Monastic Discipline and Treasure Chamber of the Abhidharma.[20] These were required courses for all monasteries of the Yellow Sect. The three monasteries used the same textbooks for the five courses, but different reference books and motes for each course. Even in the same monastery, the reference books varied from one Grwa-tshang to another. The basic contents of the Five Great Treaties were as follows.

1.Logic (rTags-rigs). This was the first course required by the three monasteries, as it was used to train students correct thinking mode and approach to study. Dharmakirti wrote this text with the purpose of explaining Pramana-samuch-chaya (Summary of the Meams to True Knowledge) by Dignaga. This text has four chapters and explains the major contents of rTags-rigs, which can be summarized into eight points. The first four points are about how to know truth, including: what is true perceptual knowledge; what is false perceptual knowledge; what is true rational knowledge; what is false rational knowledge. The second four points discuss how to instruct people to know truth and include: what is the correct way of establishing viewpoints; what is the incorrect way of establishing viewpoints; what is the incorrect way of criticizing others’ faults; what is the incorrect way of criticizing others’ faults. It would take about two years to complete this course.

2.Abhisamayalamkara (Ornament of Clear Realization). This text includes eight chapters and was written by an Indian master named Maitreya with the purpose of explaining the Mahaprajna sutra. The first three explain objective reality, that is, how to know and understand the world. The following four explain action, namely that how a Buddhist believer practices in the hope of being relieved from worldly cares. The last chapter explains fruition, namely fruits that a Buddhist believer can achieve. This text provides instruction on the procedures required to achieve enlightenment in the Buddhist sense and it would take two years to complete this text.

3. Entrance to the Doctrine of the Mean. Written by an Indian Master named Candrakirti, this text intends to introduce Nagarjuna’s dBu-ma (Madhyamika-shastra or The Doctrine Of the Mean). dBu-ma and Mind only (citta-matra) Philosophy are two schools of Buddhist theory and dBu-ma is the major foundation of the Yellow Hat Sect’s debating practice. Tsong-kha-pa’ development of dBu-ma theory has been considered a creative contribution. In addition, the Yellow Hat Sect believes that only they among Buddhist sects have the correct understanding of dBu-ma. This text includes ten chapters, starting from a believer’s thought of enlightenment to his achievement of Buddha’s fruits and benevolence. It would take about two years to complete this text.

4. Monastic Discipline. This was written by an India master named Gunaprabha (Yon-tan-vod-ang) and includes two parts illustrating 17 points related to the rules over Buddhist believers. These 17 points can also be divided into three aspects: how to receive the rules; how to keep celibacy after having received the rules, and how to return to the state of purity after the rules are violated. It would take five years to finish this text.

5. Abhidharmakosha (“Treasure Chamber of the Abhidharma〞 of mDzod) written by an Indian master named Vasubandhu. This text includes eight chapters, introducing cause and effect in the cycle of existence and approaches to relieving oneself from worldly cares. This text gives a general definition of hiragana. There was no time constraint for this course.

Buddhist theory is both profound and highly developed, so many words and terms have peculiar meanings, some of which are difficult to express in daily language. The five texts mentioned above provide only a sketchy introduction of this theory. What follows is a brief introduction to the debate-based teaching method adopted in Yellow Hat Sect monasteries. Generally speaking, there were two debating modes.

One is Dam-bcav-bzhag.[21] It means sutra debating, in which one of more monks questioned an individual. One characteristic of this debating mode was that answerers were in a passive position from beginning to the end, and all questions were put extemporarily. Questioners would first state a question clearly, and then question again and again according to the three aspects of logic, including Siddhanta (The Proposition of bsGrub-bya-bya), Hetu (reason of rTags) and Udaharana (examples in the form of analogy or dpe) in order to test whether the answerer’s view and reasoning was correct. In the course of debating, the questioners were requited to state questions clearly, so that the answer could answer with few words of simply give a yes/no answer. Generally speaking, answerers only gave a direct and short answer to the question and they would neither develop their views nor refute the questioners’ arguments. As a principle, answers should be clear and concise, except in some cases where a longer speech was obviously necessary.

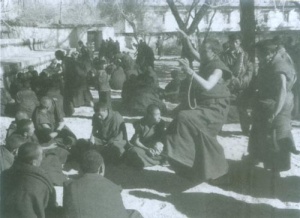

According to the tradition of the three monasteries, answerers would sit crossed-legged and have a quiet expression while questioners stood to ask questions. Sometimes they would question in a loud voice and with dynamic gestures, clapping their hands or waving their rosary. In the course of debating, the answerer remained the same one, but the questioner could be one or several who raised questions in turn. The questioned topics were restricted to the Five Great Treaties (see above) .Sometimes the topic was confined to one of the Five Great Treaties of simply a part of one text. Having a good knowledge of sutra texts was very important and the proper quotation of a piece of sutra text would frequently be decisive for one party to win a debate.

The other debating mode was called Tshogs-langs.[22] It was practiced between two monks standing face to face. When A asked B, could not refute but had to answer the questions. After doing so for a While, B began to question and A, likewise, could not refute but instead only answer. This debating rite was generally ceremonial and not as common as Dam-bcav-bzhag. All the three monasteries used Dam-bcav-bzhag rather than Tshogs-langs to test student monks.

V. Academic Semesters and Vacations

[[File:0806Champa_tongdrol_(byams-pa_mtbong-grol)_in_the_Drepung.jpg|thumb|300px|Image of Champa tongdrol (byams-pa mtbong-grol) in the Drepung Monastery)]

After dPe–cha-bas entered regular classes, they basically continued studying under their private tutors. However, they were required to come together for classes twice each day, once in the morning and once in the afternoon. The morning class was offered after the whole monastery meeting. All dPe-cha-bas had to gather at the outdoor teaching spot of their Grwa-tshang, sitting on the ground at the places arranged according to grades and waiting for the start of the class. These outdoor teaching spots were called Chosrwa, [23] which was comparable to sutra courtyard in the hinterland and was generally situated near the center of a Grwa-tshang. It was a spacious square with trees and a teaching arena. During the class time, Dge-sKos of each Grwa-tshang along with their assistants with wands in hand walked around to maintain order in class. The class included two activities. One was mKhan-po’s instruction of sutra texts. However, it was not held very frequently. When mKhan-po came to the arena and sat down with crossed legs, dPe-cha-bas would prostrate themselves on the ground before him and listen to his teaching of Sutras grade after grade. His teaching only lasted several minutes for each grade, giving a sketchy instruction of a piece of test and then waving this grade to withdraw. The next grades would take the class the same way. When there were no such teaching activities. Student monks learned to debate on their own. This was the second class activity. Two to three of five to six monks formed a group within which they used the form of Dam-bcav-bzhag to question one another. They did not go back to their Khams-tshan until noon. The second Chos-rwa held held at about five o’clock in the afternoon of the same day. dPe-cha-bas gathered at the sutra courtyard, reading sutras of practicing debates, and they were dismissed at eight or nine o’clock. Afterwards they went back to self-study of sleep at their Khams-tshans.

This was the timetable for an ordinary dPe-cha-ba. Generally speaking, the monasteries did not keep a strict supervision over dPe-cha-bas’ attendance at classes and their study performance. If some dPe-cha-bas, especially Rin-po-ches, preferred to stay at the Khams-tshan to learn under their private tutors or to self-study, this would be permitted.

Like ordinary schools, the three monasteries had two semesters for each academic year. According to the Tibetan calendar, the first semester was from the eng of the first month or the beginning of the second month to the middle of the sixth month. This semester was further divided into four sessions with a short vacation after each session. In addition, there was a 12-day religious ceremony called Tshogs-mchod[24] in the second or third ten-days of the second month. In the sixth month, all the three monasteries had one and a half month vacation called Chos-mtsams-chen-po,[25] meaning〝big vacation〞.

After this vacation, from the beginning of the eighth month to the third ten days of the twelfth month was the second semester. In the Se-ra Monastery, this semester included three sessions; in the vBras-spungs and dGav-ldan monasteries, it had four. After each session, there was a short vacation. From the second and third ten-day periods of the twelfth month was the New Year holiday. During the first days of the Tibetan New Year, the monks of the three monasteries gathered at Lhasa to attend the sMon-lam-chen-po[26] religious ceremony, which would last 21 days.

The foregoing is an introduction to the academic year and holidays of the three monasteries. As the monasteries attached great importance to rTags-rigs and debating, there were two continuation classes of rTags-rigs before or after summer and winter vacations. At Chu-shur, southwest of Lhasa, is a monastery called Rwa-stod-grwa-tshang[27] that is famous for the teaching of rTags-rigs. Every year from the beginning of the eleventh month to the second ten-day period of the twelfth month according to the Tibetan calendar, this Grwa-tshang offered a lecture on rTags-rigs, called vJam-dbyangs-dgun-mchod, namely the winter lecture at vJam-dbyangs (a place name). All dPe-cha-bas of the three monasteries could attend it. During the long vacation in summer, Rwa-stod-grwa-tshang held a lecture on rTags-rigs at bZang-po. It was called bZang-po-dbyar-mchod, namely the summer lecture at bZang-po (a place name). All dPe-cha-bas of the three monasteries could also attend it. However, dPe-cha-bas attending the winter lecture were much grater in number than those attending the summer one, as monks of the monasteries would go to practice on their own in small temples nearby every summer. Therefore, the vJam-dbyangs-dgun-mchod was more renowned than bZang-po-dbyar-mchod.

VI. dPe-cha-bas' Examination, Graduation and Academic Degree

As the three monasteries seldom tested their dPe-cha-bas in the process of their study, dPe-cha-bas’ rise in grade was only a formality. As mentioned above, dPe-cha-bas of the same grade sit in a group in the sutra courtyard. All dPe-cha-bas who entered regular classes in the same year were placed in the same grade. In every ninth Tibetan month when a new dGe-sKos (monk in charge of monastic disciplines) replaced the previous one and came into office, each dPe-cha-ba in the monasteries was promoted to a grade. In this way, a dPe-cha-ba could move up a grade every year until he reached vDzin-dang-po, the highest grade. During the process of study, if a dPe-cha-ba asked for leave because of illness or other businesses, he could be absent from the monastery for one, two or more years with the approval of his Grwa-tshang. When he came back, he was still allowed to join his original grade and the period of his absence could be considered to be valid study time.

Though dPe-cha-ba was seldom officially tested from his lowest to highest grade, gZhung-las-pa and dGe-skos frequently came to inspect them when they were learning to debate, and reported their performance to mKhan-po. In addition, each dPe-cha-ba was required to recite twice a year the sutras he was learning for at least 50 pages before the mKhan-po. When a dPe-cha-ba had studied for an adequate number of years and his performance was up to a certain standard, the mKhan-po would give him an opportunity to take Tshogs-langs and prepared him to receive an academic degree.

The student monks who were approved to receive Tshogs-langs could practice debating in any Khams-tshan of his Grwa-tshang and preside over all debates in the form of Dam-bcav-bzhag by asking other monks to question him. By doing so he could practice his debating skills with all good students in his Grwa-tshang. In addition, he had opportunities to participate in debates in other Grwa-tshangs. This type of debating activity was frequently jointly held by two closely related Grwa-tshangs. The monks from the two Grwa-tshangs learned debating skills from each other by questioning the monks from the other.

The form of debating mentioned above was Dam-bcav-bazhag, that is, many monks questioned a monk. Finally, the two Grwa-tshangs would jointly hold formal Tshogs-langs in the Tshogs-chen Grand Hall of the Monastery. The contestants were monks with the same education level from the two Grwa-tshangs, and the debating content was on the sutra book they were currently studying. After party A questioned party B for a while, B began to question A. The result of these Tshogs-langs was not an official assessment for the monks’ academic degree. However, it provided the heads and all monks of this monastery with a clear view of a monk’s academic performance and based on this decided whether a monk could have a degree or not, though it was a long time before he took formal graduation examinations.

Any dPe-cha-ba in the grade of vDzin-dang-po was qualified to take the examination for an academic degree called dGe-bshes[28] in the system of the three monasteries. The DGe-bshes degree had four grades, including Lha-rams-pa, Tshogs-rams-pa, gLing-bSres and rDo-rams-pa (in the vBras-spungs and dGav-ldan Monasteries) or Rigs-rams-pa (in the Se-ra Monastery) [29] Lha-rams-pa and Tshogs-rams-pa were the advanced dGe-shes of the monasteries. As the quota of the two degrees was limited for each year, the three monasteries had to take turns in conferring them to students. All those who applied for the two types of dGe-shes were required to take a re-examination offered by the highest authority in Lhasa and a public test in addition to the examination given by their own monastery. The other two types of dGe-shes degree were conferred within the three monasteries respectively. The quota for the two degrees each year was also decided by the monasteries and was then distributed to the Grwa-tshangs, which would offer examinations and decided which candidates should be awarded degrees.

The internal dGe-shes examinations of the three monasteries were held in the eighth Tibetan month. It was mKhan-po who selected candidates, designed the examination papers and supervised the examination. Candidates took oral examination one by one in the order of age or years of education. The examination questions for each candidate varied but the testing form was all Dam-bcav-bzhag. The mKhan-po would appoint five senior monks to question each candidate. The reason for the use of five questioners was that every question master was responsible for one of the Five Great Treaties mentioned in part IV. In this sense, it was a comprehensive test for the candidates.

When the examination was held, the examinee sat before the mKhan-po and one of the question masters went to bow before the mKhan-po permission to begin asking the questions. After the mKhan-po had told him questions, he went to question examinee until the mKhan-po thought it was proper time to end. Afterwards, the other four question masters question him one after another as before. Then the second candidate took the examination in the same manner, though facing different questions. The next day, the mKhan-po called together all the candidates to his place for the results. According to the performance in the examination, candidates were officially conferred one of the four degrees of dGe-shes. Those awarded gLing-bsres, rDo-rams-pa or Rigs-rams-pa dGe-shes need not to take further examinations, but those receiving Lha-rams-pa and Tshogs-pa dGe-shes had to take the two re-sit examination mentioned above.

The first re-sit examination was held in the tenth Tibetan month. All Lha-rams-pa and Tshogs-rams-pa dGe-shes who had passed the preliminary test offered in their monasteries went to Norbu glingkha Summer Palace of Dalai lama to take a further test in form of debating, which was supervised by dGav-ldan-khri-pa, the highest authority of sutra studies of the there monasteries and Dalai Lama’s attendant officers. The second re-sit examination was offered in the religious ceremonies of the Tibetan New Year, namely sMon-lam-chen-po and Tshogs-mchod.

During the period of the two religious ceremonies, all monks of the Yellow Sect from the three monasteries and those nearby gathered at the Jo-khang Temple to chant sutras and practice religious rites. sMon-lam-chen-po was much greater in scale than Tshogs-mchod. Each Lha-rams-pa and Tshogs-rams-pa who had passed the first re-sit examination would have a day of debating in public. The debating date for Lha-rams-pa would be arranged in the period of sMon-lam-chen-po and the date for Tshogs-rams-pa would be in the period of Tshogs-mchod. On the given date, they would conduct public debates three times. The first was in the morning and the examinee would answer questions in the teaching arena of dGav-ldan-khri-pa. The other two were held in the afternoon in the Grand Hall of Jokhang Temple and both of them were supervised by two mKhan-pos appointed by the vBras-spungs Monastery. Every year during the two ceremonies, Lhasa was filled with many monks. Any dGe-bshes and top students from the monasteries could post questions to the Lha-rams-pa and Tshogs-rams-pa in order to test their religious knowledge. Especially at the first half of sMon-lam-chen-po, there were a very large number of questioners, and most of the Lha-rams-pas arranged to debate at that time were the most knowledgeable.

Generally speaking, except for the first seven monks with Lha-rams-pa degree, monks with dGe-shes degree at each rank did not have official positions, and the positions of the first seven monks with Lha-rams-po degree were decided after the public test at sMon-lam-chen-po. According to tradition, monks who had been admitted to the dGe-shes at any rank would offer tea and rice (similar to eight-treasure rice pudding in the hinterland) to all monks at the Grand Hall of his Grwa-tshang, as ceremonial delicacies. If a monk with dGe-shes degree were sufficiently wealthy, he would give some money to all the monks of his Grwa-tshang or Khams-tshang, or donate money in the form of funding for monastery’s expenditure. On the same day, the authorities of the Grwa-tshan, or donate money in the form of funding for monastery’s expenditure. On the same day, the authorities of the Grwa-tshang would have a dedication prayer tied to a wooden arrow one zhang (3.3meters) in length and have a person hold it high and walk around once inside the hall. This ceremony was comparable to the graduation ceremony in modern schools. In addition, on this day a special seat was arranged for the monks with dGe-shes degress so that he could sit there receiving congratulations. Apart from the monks of this monastery, his relatives, friends and patrons would also come to give him presents and an auspicious scarf. Besides giving gifts in return, he would prepare meals to entertain these guests, just as people in the inter land celebrated happy events. In addition, he would give presents to all administrative officials of his Grwa-tshang or Khams-tshan, and serve them with tea and food. If the monk with dGe-shes degree was a Rin-po-che, his celebrations would be much more extravagant to match his status. Sometimes the cost of this activity was surprisingly high. However, Tibetans considered winning a dGe-shes degree in the three monasteries was a big event symbolizing an achievement in both happiness and intelligence. Therefore, it was worthwhile celebrating with ceremony.

VII. The Highest Academic Institute and Highest Achievement of dPe-cha-bas

Getting a dGe-shes degree was similar to getting an academic degree upon graduation in hinterland universities. However, monks with dGe-shes degrees need not leave the monastery immediately after getting the degree. As a matter of fact, many of them stayed in the monastery and eventually became senior monks. They could take in novice monks to teach sutras, attend and make proposals at all meetings in their Khams-tshan. With increasing seniority and reputation, they could be appointed abbot of dependant monasteries, or an important official or mKhan-po in his Grwa-tshang. In addition, monks with dGe-shes degrees who could like to continue their Buddhist studies could become graduate students in two rGyud-smad-grwa-tshang and rGud-stod-grwa-tshang.[30]

As mentioned above, novice monks of the Yellow Hat Sect began with Sutra and then studied Tantra. Both the dGav-ldan and vBras-spung monasteries had sNgags-pa Grwa-tshangs, which specialized in teaching how to chant sutras and spells, and how to hold rites to pray for gods’ blessings and to dispel evil spirits and disasters. The nature of the two sNgags-pa Grwa-tshangs was similar to that of a professional training program. They were independent systems and quite different from Sutra Grwa-tshangs in the Dgav-ldan and vBras-spung monasteries. As for rGyud-smad-grwa-tshang and rGud-stod-grwa-tshang, they were the highest Tantric research institutes of the three monasteries. All regular students of the two institutes were monks with dGe-shes degree from the three monasteries, namely student monks who had studied the Sutra for a long time, especially Lha-rams-pas, the first rank of dGe-shes.

At present, there are two types of student monks in rGyud-smad-grwa-tshang and rGud-stod-grwa-tshang. One is rDzogs-rim-pas[31], who have achieved the dGe-shes degree and go there for further study as regular students; the other is skied-rim-pas, who are irregular students of the two Grwa-tshangs and also from the three monasteries, but they have no dGe-shes degree. Renowned for their rigorous scholarship, strict discipline and stress on ascetic practice, the two Grwa-tshangs have won high praise and respect in Tibetan society. In the two Grwa-tshangs, all students are equal and even those with sPrul-sku and Chosmdzad status are not treated more favorably. However, there are slight differences in admission procedures between rDzong-rim-pas coming from monks with dGe-shes degree and skyed-rim-pas from ordinary monks.

When monks with dGe-shes degree from the three monasteries applied for the entry into the two institutes, they had first to ask a senior monk in the institutes to be a guarantor, who would then submit their application to the mKham-po via the head of the Khams-tshan. According the procedures, the applicant would be submitted three times within at least half a month. If accepted, the applicant would be allowed to put a cushion on the floor of the Grand Hall. In the rGyud-smad-grwa-tshang, the mKham-po would routinely test the new student’s sutras in person while in the rGyud-Stod-grwa-tshang, the initiate was required to submit himself to public debate in the sutra courtyard where the other monks would question him. The initiate could not be accepted officially until be passed the test. If he failed, he would be expelled immediately and his guarantor would be punished severely.

For an ordinary monk who applied to the two institutes, he would first hire a private Sutra teacher and memorise all required Tantra texts. Then he would ask a guarantor to introduce him to recite Sutras before one of the heads of the Khams-tshan. If he passed this preliminary test, the head of the Khams-tshan would recommend him to mKham-po, which could be regarded as a formal application. This procedure would also be repeated three times within a fortnight. With the mKham-po’s approval, the applicant could be on probation for two weeks as a student. During the probation period, he had to read sutras in the courtyard outside the Grand Hall when all other monks were having a rest inside. He was forbidden to sleep until tow o’ clock in the morning. When he had completed the probation period, he was required to re-sit the examination in the form of reciting Sutras, which was offered by the Grwa-tshang authorities. He could not be an official skied-rim-pa until he had passed this examination.

In light of the regulations of the two Tantric institutes, new students had to undergo a〝study tour〞 in which they traveled to some appointed places to study Tantras according to a traditional schedule. The study period was one year for rDzong-rim-pa and nine years for skied-rim-pa.

As in the institutes, the student monks were required to take classes four times in the Grand Hall each day and study their lessons as normal in other monasteries they traveled to. From the fifteenth day of the seventh Tibetan month to the end of the eighth Tibetan month was a long vacation, during which all students o the two institutes went to the appointed small temples to live and practice on their own. Around the twentieth of the eleventh Tibetan month, all administrative officials and monks got together at the dGav-Ldan Monastery to hold a religious ceremony. At the end of a Tibetan year, the students also had a short vacation and thereafter they would take part in sMon-lam-chen-po and Tshogs-mchod religious ceremonies during the first days of the Tibetan New Year, as the other monks of the three monasteries did.

The following is a brief outline of the daily schedule in the two institutes. The first Grand Hall class started very early, just after two 0’clock in the morning, including chanting Sutras together. During the class time, the monastery would offer the students tea and porridge for breakfast. In addition, students were allowed to bring rTsam-pa (barley flour) with them. After they finished their first class at seven 0’s clock, different classes of students would take turns to go to the Sutra countryard outside to listen to the mKhan-po’s instruction in sutras. This was similar to the teaching mode of the three monasteries mentioned above. If there were no mKham-po’s teaching, students would study by themselves. Around nine 0’clock in the morning, students would get together in the Grand Hall for a second time to chant Sutras for one hour. After that, the students who had been in the monastery for nine or more years could go back to their Khams-tshan to rest or self-study while others had to stay and self-study in the Sutra courtyard.

When studying in the sutra courtyard, every student had his own seat, which was a one-meter-deep pit with the capacity for one person. The bottom of the pit was paved with stone slabs on which students sat without a cushion or a cover. This was the case all year round even in windy or rainy days.

They did not have the third class until noon. When students were chanting sutras together, they were offered a second round of tea and porridge. Though students were also allowed to have their own rTsam-pa, the rTsam-jpa bags had to be taken out of the hall when the class was over, as it was stipulated that monks should not eat anything after noon. At the end of this class, rTsam-pa bags were passed down from the first monk in each row to the last who was responsible for tying them up and keeping them until the first class in the early morning of the next day.

The fourth class started at about four 0’clcok in the afternoon and they chanted Sutras together for around one hour before the end of the class. However, it would not finish until eight or nine in the evening if there were a special religious ceremony. After nine 0’ clock, all monks would get together in front of the Grand Hall of their Grwa-tshang and wait for the order of the dGe-skos. When he asked them in the monks would go into the hall one after another, take their own seat, wrap themselves with their big cloaks, and huddle themselves up, all sleeping on their right side. After the Dge-sKos’s inspection around the Hall, the door was locked until about two 0’clock in the nest morning, before the first class of the next day.

According the age and education level, the student monks of the two institutes were classified into five grades. However, in fact there was no time restriction for the students in the two institutes as there were no examination, graduation or any academic degrees for them. Most of the students would leave the two institutes automatically when they had studied there for a sufficiently long time. The main courses offered in the two institutes were Tantras of the three Tantric knife-deities, namely Gsang-ba-vdus-pa, dDe-mchog and vJigs-byed[32]. In addition, they studied Tantras on secondary Tantric knife-deities (Vajrayana) and the guardian deity. The basic textbook they used was a series of texts named rGyud-gzhung, [33] which is a Tantric Classics. In addition, they had a large number of reference texts.

Simply put, the difference between Tantra and Sutra was that the former was only taught to believers under required conditions (namely ritual instruments or one who obeys the Buddha) while the latter could be transmitted to ordinary believers. This was the reason why the Yellow Hat Sect of Buddhism believed that Sutra should be learnt before Tantra. Like other Buddhist sects, the Yellow Hat Sect also stressed that a believer could not reach the highest level of Buddhism without learning Tantra.

The two Tantric institutes had a separate promotion system for the first rank of dGe-shes (student monks with Lha-rams-pa degree) especially those at the first seven positions. The achievement of these monks represented the highest level in the process form Sutra to Tantra studies. Only this group of monks in the two institutes could be promoted rank by rank and finally reach the position of mKhan-po according to seniority and educational achievement. After retiring from this position, they could continue to be promoted to two sublime positions, that is, Shar-rtse-chos-rje and Byang-rtse-chos-rje.[34] According to tradition, Shar-rtse-chos-rje was assumed by the oldest mKhan-po retired from the rGyud-stod-grwa-tshang. Shar-rtse-chos-rje and Byang-rtse-chos-rje were completely equal in status. Every seven years, the two took turns to be dGav-ldan-Khri-pa, the highest authority of Sutra studies in the three-monastery system.

The title of dGav-ldan-Khri-pa means the successor of the seat of Dharma in the dGav-ldan Monastery, the birthplace of the Yellow Hat Sect. It is said that this monastery now still keeps the Dharma-throne of Tsong-kha-pa. After his Nirvana, this throne was taken over in turn by two of his disciples-rGyal-tshab-rje and Mkhas-grub-rje, and thereafter the tradition of passing on the Dharma-throne has been established ever since. Tsong-kha-pa, rGyal-tshab-rje and mKhas-grub-rje were greatly worshiped by all believers of the Yellow Hat Sect and they wear called〝rJe-yab-sras-gsum (three saints in the father-and-son relationship)〞.[35] It has been explained that dGav-ldan-khri-pa, Shar-rtse-chos-fje and Byang-rtse-chos-rje perfectly symbolized Tsong-kha-pa and the two disciples. All those who became dGav-ldan-khri-pa, Shar-rtse-chos-rje and Byang-rtse-chos-rje were not only worshiped and given offerings by Buddhist believers, but also generally recognized as Rin-po-ches who could be reincarnated generation after generation. In the eyes of ordinary monks, they were typical examples of a belief, that is, an ordinary person could achieve the Buddhist fruits (liberation or salvation) through all his life-long efforts in study and ascetic practice.

Footnotes

- ↑ There are two interpretations of dGe-ldan Monastery; One holds that it is the sect of dGav-ldan Monastery; the other believes that it means a virtuous sect. Scholars of Tibetology have not agreed on a final conclusion about its meaning.

- ↑ Sa-skya-pa Sect was the descendant of vKhon family. This sect had started in the mid 11th century when the Precious King dKon-mchog-rgyal-po built a monastery in the place named Sa-skya. It reached its peak in the 13th century and declined in the mid 14th century. Now the head of this sect is assumed in turn by a member from the two branches of this clan.

- ↑ Bkav-brgyud-pa Sect rose at the beginning of the 12th century and reached its peak in the 14th and 15th century. Later this sect was divided and claimed to have four major and eight sub-sects. Today this sect has three or four branches.

- ↑ The major branches of Bkav-brgyud-pa Sect, such as Tshal-pa, vBri-gung-pa and Phag-mo-grub-pa, were controlled by aristocratic clans. Rin-sprungs-pa and gTsang-pa, supporters of this sect in a later period, were all laymen. They governed Central Tibet or Western Tibet (U-gTsang region) successively. From the 14th century to the 16th century, Tibet was in turbulence and saw incessant wars.

- ↑ The〝Four Major Monasteries of the Yellow Sect〞 are called lDan-sa-bzhi in Tibetan. They were built as follows: the dGaav-ldan Monastery (1409, the 7th year of Ming Emperor Chengzu’s reign;) the VBras-Spungs Monastery (1415, the 13th year of Emperor Chengzu’s reign); the Se-ra Monastery (1418, the 16th year of Emperor Chengzu’s reign) and the bKra-shis-lhun-po Monastery (1447, the 12th year of Ming Emperor Yingzong’s reign). It is true that the establishment of the Yellow Hat Sect’s political power relied on support from the Mongols and the Qing Government, but this sect maintained a high degree of independence, which distinguished it from other sects constantly controlled by outside forces.

- ↑ In the other sects of Tibetan Buddhism, there was no such complete and well-organized structure as dPe-cha-ba. In the Yellow Hat Sect, the most important Rin-po-ches such as Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama were members of the dPe-cha-ba system.

- ↑ Attaching importance to debating is a leading characteristic of the Yellow Hat Sect. Among four colleges of the vBras-spungs Monastery, three were mTshan-nyid-based colleges. Among three colleges of the Se-ra Monastery, two were mTshan-nyid-based. Both colleges of the dGav-ldan were mTshan-nyid-based.

- ↑ Generally speaking, dPe-cha-ba did not have much chance to be an official. However, if a common monk was selected to be attendant officer and Sutra teacher of the Dalai Lama (or Panchen Erdenis) after achieving the highest academic degree, he would be likely to start a political career. For example, dGav-ldan-Khri-pa in Central Tibet was qualified to be a regent (see below). It was more common for a dPe-cha-ba who was a Rin-po-che to have political power.

- ↑ Grwa-tshang is an abbreviation of Grwa-pavi-tshang. In Tibet, ordinary monks were called Grwa-pavi while Tshang was a general title for the legal person of a group of monks and all of their property. Grwa-tshang was an independent component and some small temples were also called Grwa-tshang.

- ↑ This characteristic of Khams-tshan was not very strictly based on the place where monks came from. According to tradition, monks from different regions were frequently arranged to live in the same Khams-tshan, and monks from the same region probably lived in several Khams-tshans. In a larger Khams-tshan, there was probably a structure named Mi-tshan.

- ↑ mKhan-po is comparable to abbots of monasteries in the hinterland.

- ↑ dBu-mdzad is akin to head sutra chanter. gZhung-las-pa’s literal translation is the person who is in charge of learning affairs. DGe-sKos is partially similar to the person maintaining order in monasteries in the hinterland. The three posts are altogether called dBu-chos-gsum. (see explanation below). The name and function of the three positions in the three monasteries were similar in a general sense, though there were some differences.

- ↑ As soon as dPe-cha-bas came into bsDus-grwa classes, they began to learn basic debating skills. If some were too young or illiterate, they were apprenticed to a teacher and started with the alphabet.

- ↑ There are two interpretations of dGe-ldan Monastery; One holds that it is the sect of dGav-ldan Monastery; the other believes that it means a virtuous sect. Scholars of Tibetology have not agreed on a final conclusion about its meaning.

- ↑ The literal meaning of vDzin-dang-po is the first grade, that is, the highest grade.

- ↑ Some may not be willing to regard Rin-po-che’s favorable treatment as privileges, but this is indeed what they were. Some dPe-cha-bas had the identity of sPrul-sKu, but they were treated as Chos-mdzad (explained below). This illustrates that Rin-po-ches’ privileges were not a natural product but instead a favorable treatment gained according to social status.

- ↑ sPrul-sKu literally means incarnation

- ↑ Chos-mdzad means putting teachings into practice and being a paragon of virtue and learning

- ↑ Tshogs-chen refers to the Hall of Your Majesty in a monastery, so the organizations at monastery level are all expressed with Tshogs-chen. According to tradition, among Rin-po-ches within the system of the three monasteries, some were ranked as Tshogs-chen and some as Grwa-tshang. Their status could not change freely. Even Rin-po-ches at Tshogs-chen level were further classified into three ranks, ches at Tshogs-chen level were further classified into three ranks, namely large, medium and small, and the local government of Tibet had strict stipulation over the rank differentiation.

- ↑ The Tibetan abbreviation of the five required courses are: rTags-rigs, Phar-phyin, dBu-ma, vDul-ba, and mDzod.

- ↑ “bZhag〞 in〝Dam-bcav-bzhag〞 is a verb, which means〝practice〞 in〝practicing debating〞. In the Chinese language, this debating mode is called〝practicing Dam-bcav〞.

- ↑ Tshogs-langs literally means standing in meeting. Here it means debating.

- ↑ Chos-rwa were religious gardens in hinterland monasteries. This term was also used in Tibetan monasteries to refer to having classes.

- ↑ The literal meaning of Tshogs-mchod is Prayer Ceremony.

- ↑ Chos-mtsams-chen-po is similar to the summer vacation of modern schools, during which monks generally went to a small temple to practice meditation in seclusion.

- ↑ sMon-lam-chen-po literally means Greater Prayer Ceremony. Both Greater Prayer Ceremony and lesser Prayer Ceremony were held in the gTsug-lag-khang Monastery of Lasha.

- ↑ Rwa-stod-grwa-tshang was an independent Grwa-tshang, but it was within the system of the three monasteries and had a close relationship with the vBras-spungs Monastery. The three monasteries allowed it to test dGe-bshes (see below).

- ↑ The literal meaning of dGe-bshes is expert of knowledge, which is an abbreviation of dGe-bavi-bsheis-gnyen.

- ↑ The five degrees of dGe-bshes: Lha-rams-pa, Tshogs-rams-pa, gLing-bSres, rDo-rams-pa, and Rigs-rams-pa.

- ↑ rGyud-smad-grwa-tshang means the Lower Tantra Institute while rGyud-stod-grwa-tshang means the Upper Tantra Institute. The two translations may cause misunderstanding regarding the academic level of the two institutes. In fact, they are of equal status, though rGyud-smad was established earlier than rGyud-stod. In Tibet,〝Smad〞 and〝Stod〞 express northeast and southwest, so some people explain that rGyud-smad and rGyud-stod got their names for their location at the northeast and the southwest of Lhasa. Theoretically speaking, the two Grwa-tshang belonged to the dGav-ldan Monastery, but it actually had equally close relationships with the other two monasteries.

- ↑ rDzogs-rim-pa means practicing for achievement, which is the highest stage of Tantra (Esoteric Buddhism).

- ↑ Gsang-ba-vdus-pa, Dde-mchog, and vJigs-byed are the names of three Tantric knife-deities in the Tantric institutes. They are generally abbreviated to gSang-dbe-vjigs-gsum. As seen in ordinary monasteries, gSang-ba-vdus-pa and dDe-mchog are double-bodied statues, and vJigs-byed is a statue with an ox head and a wrathful face.

- ↑ rGyud-gzhung is a classic of gSang-ba-vdus-pa, or a collection of Tantric essentials.

- ↑ “Shar-rtse〞 in Shar-rtse-chos-rje and〝Byang-rtse〞 in Byang-rtse-chos-rje were the names of two Grwa-tshangs in the dGav-ldan Monastery and meant east mountain peaks〞 and north mountain peaks〞 and〝north mountain peaks〞, as the first Grwa-tshang of the monastery was built on the east peak and second on the north peak. The meaning of〝chos-rje〞 is〝religious saint〞. The two saints were named after the two Grwa-tshang of the dGav-ldan Monastery representing the original relationship between the two Tantric institutes and the dGav-ldan Monastery.

- ↑ The term of〝rJe-yab-Sras-gsum〞 uses the father-and-son relationship to express the relationship between teacher and students. This comparison is common in Buddhism.