Difference between revisions of "The Paradox of Causality in Mādhyamika By David Loy"

m (1 revision: Robo text replace 30 sept) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

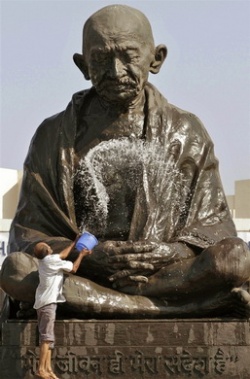

[[File:Ess.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Ess.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | THE PROBLEM of [[causality]] is central to all schools of [[Buddhism]], and this is especially true of [[Mādhyamika]]. But at first glance there seems to be a contradiction in the [[Mādhyamika]] analysis. On the one hand, [[causal]] [[interdependence]] is clearly a crucial {{Wiki|concept}}, so important that [[Nāgārjuna]] identifies it with the most important {{Wiki|concept}}, [[śunyatā]]: "We interpret the [[dependent arising]] of all things ([[pratītyasamutpāda]]) as the absence of [[being]] in them ([[śunyatā]])." [1] This emphasis on [[interdependence]] develops to completion the early [[Buddhist doctrine]] of [[impermanence]]: there are no [[unconditioned]] [[elements]] of [[existence]] ([[dharmas]]), for all things arise and pass away according to [[conditions]]. The undeniable relativity of everything is the means by which self-existence ([[svabhāva]]) is refuted. | + | THE PROBLEM of [[causality]] is central to all schools of [[Buddhism]], and this is especially true of [[Mādhyamika]]. But at first glance there seems to be a {{Wiki|contradiction}} in the [[Mādhyamika]] analysis. On the one hand, [[causal]] [[interdependence]] is clearly a crucial {{Wiki|concept}}, so important that [[Nāgārjuna]] identifies it with the most important {{Wiki|concept}}, [[śunyatā]]: "We interpret the [[dependent arising]] of all things ([[pratītyasamutpāda]]) as the absence of [[being]] in them ([[śunyatā]])." [1] This {{Wiki|emphasis}} on [[interdependence]] develops to completion the early [[Buddhist doctrine]] of [[impermanence]]: there are no [[unconditioned]] [[elements]] of [[existence]] ([[dharmas]]), for all things arise and pass away according to [[conditions]]. The undeniable [[relativity]] of everything is the means by which self-existence ([[svabhāva]]) is refuted. |

| − | At the same [[time]], [[Nāgārjuna]] redefines [[pratītyasamutpāda]] in such a way as to negate [[causality]] altogether. This is apparent even in the prefatory [[dedication]] of the Mūlamādhyamikakārikās, in the eight negations which [[Nāgārjuna]] attributes to the [[Buddha]]: | + | At the same [[time]], [[Nāgārjuna]] redefines [[pratītyasamutpāda]] in such a way as to negate [[causality]] altogether. This is apparent even in the prefatory [[dedication]] of the Mūlamādhyamikakārikās, in the [[eight negations]] which [[Nāgārjuna]] [[attributes]] to the [[Buddha]]: |

| − | Neither perishing nor arising in [[time]], | + | Neither perishing nor [[arising]] in [[time]], |

neither terminable nor [[eternal]], | neither terminable nor [[eternal]], | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

Such [[pratītyasamutpāda]].. . .[2] | Such [[pratītyasamutpāda]].. . .[2] | ||

| − | Consistent with this, the first and most important chapter of the Kārikās concludes that the [[causal]] relation is inexplicable, and later chapters go further to claim that [[causation]] is like [[māyā]]. "Origination, [[existence]], and [[destruction]] are of the nature of [[māyā]], [[dreams]], or a fairy castle." [3] The last chapters seize on this issue as one way to crystallize the [[difference]] between [[saṁsāra]] and [[nirvāna]]. The [[nirvāna]] chapter distinguishes between them by attributing [[causal]] relations only to [[saṁsāra]]: "That which, taken as [[causal]] or dependent, is the process of [[being]] born and passing on, is, taken non-causally and beyond all dependence, declared to be [[nirvāna]]." [4] In his commentary on the previous chapter, [[Candrakirti]] defines saṁvṛti and [[duḥkha]] in the same way: ". . .to be reciprocally dependent in [[existence]], that is, for things to be based on | + | Consistent with this, the first and most important [[chapter]] of the [[Kārikās]] concludes that the [[causal]] [[relation]] is inexplicable, and later chapters go further to claim that [[causation]] is like [[māyā]]. "Origination, [[existence]], and [[destruction]] are of the [[nature]] of [[māyā]], [[dreams]], or a fairy castle." [3] The last chapters seize on this issue as one way to crystallize the [[difference]] between [[saṁsāra]] and [[nirvāna]]. The [[nirvāna]] [[chapter]] distinguishes between them by attributing [[causal]] relations only to [[saṁsāra]]: "That which, taken as [[causal]] or dependent, is the process of [[being]] born and passing on, is, taken non-causally and beyond all [[dependence]], declared to be [[nirvāna]]." [4] In his commentary on the previous [[chapter]], [[Candrakirti]] defines saṁvṛti and [[duḥkha]] in the same way: ". . .to be reciprocally dependent in [[existence]], that is, for things to be based on |

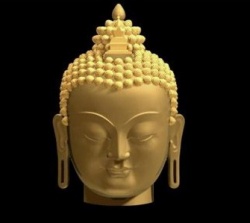

[[File:F1qz6.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:F1qz6.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [1] Mūlamādhyamikakārikās (hereafter "MMK') XXIV 18, in Lucid Exposition of the [[Middle Way]]: The [[Essential]] Chapters from [he Prasannapada of andrakirti, trans. Mervyn Sprung (Boulder: [[Prajña]] Press, 1979), p. 238. This identification must be kept in [[mind]] to avoid Śaṅkara's error of misinterpreting sunyaia as non-being and making [[Mādhyamika]] into a [[nihilism]]. | + | [1] Mūlamādhyamikakārikās (hereafter "MMK') XXIV 18, in Lucid [[Exposition]] of the [[Middle Way]]: The [[Essential]] Chapters from [he [[Prasannapada]] of andrakirti, trans. Mervyn Sprung (Boulder: [[Prajña]] Press, 1979), p. 238. This identification must be kept in [[mind]] to avoid [[Śaṅkara's]] error of misinterpreting sunyaia as [[non-being]] and making [[Mādhyamika]] into a [[nihilism]]. |

[2] I bid., pp. 32-33, 35. For [[pratītyasamutpāda]] Sprung gives "the true way of things." | [2] I bid., pp. 32-33, 35. For [[pratītyasamutpāda]] Sprung gives "the true way of things." | ||

| − | [3] MMK VII 34, as quoted in T. R. V. Murti, The Central [[Philosophy]] of [[Buddhism]] ({{Wiki|London}}: Allen and Unwin, 1960), p. 177. | + | [3] MMK VII 34, as quoted in T. R. V. [[Murti]], The Central [[Philosophy]] of [[Buddhism]] ({{Wiki|London}}: Allen and Unwin, 1960), p. 177. |

| − | [4] MMK XXV 9, in Sprung, p. 255. In my opinion this is the most important verse in the Kārikās. | + | [4] MMK XXV 9, in Sprung, p. 255. In my opinion this is the most important verse in the [[Kārikās]]. |

p64 | p64 | ||

| − | each other in utter reciprocity, is saṁvṛti." ". . it is precisely what arises in dependence that constitutes [[duḥkha]], not what does not arise in dependence." [5] | + | each other in utter reciprocity, is saṁvṛti." ". . it is precisely what arises in [[dependence]] that constitutes [[duḥkha]], not what does not arise in [[dependence]]." [5] |

| − | How are we to understand this obvious contradiction? That is, how do we get from interpreting [[pratītyasamutpāda]] as "[[dependent origination]]" to "non-dependent non-origination," and, what is more, reconcile the two? Explanations which differentiate between two different types of [[sutras]] ([[exoteric]] [[neyārtha]] and [[esoteric]] [[nītārtha]]), or which refer to the two-truths {{Wiki|theory}}, just raise the same question in a different [[form]], for we need to know how such contradictory [[truths]] can both be true, i.e., how these two are related to each other. | + | How are we to understand this obvious {{Wiki|contradiction}}? That is, how do we get from interpreting [[pratītyasamutpāda]] as "[[dependent origination]]" to "non-dependent [[non-origination]]," and, what is more, reconcile the two? Explanations which differentiate between two different types of [[sutras]] ([[exoteric]] [[neyārtha]] and [[esoteric]] [[nītārtha]]), or which refer to the two-truths {{Wiki|theory}}, just raise the same question in a different [[form]], for we need to know how such [[contradictory]] [[truths]] can both be true, i.e., how these two are related to each other. |

| − | This paper will offer one way (perhaps not the only way) of resolving this problem, which may more properly be said to be a [[paradox]]. I shall argue that complete conditionality is phenomenologically equivalent to a denial of all [[causal]] [[conditions]]. That is, a [[view]] which is so radical as to analyze things away into "their" [[conditions]] is [[offering]] an interpretation of [[experience]] which becomes indistinguishable from a [[view]] that negates [[causality]] altogether. If this is true, we have another instance where it becomes very difficult to distinguish the [[Mādhyamika]] [[nonduality]] from that of Śaṅkara's {{Wiki|Advaita Vedānta}}. [6] The argument will be made in two steps. We shall see that there is a [[dialectic]] inherent in the [[Mādhyamika]] analysis. The first stage (discussed in Part I) is apparent: looking at the {{Wiki|common-sense}} distinction between things and their [[cause-and-effect]] relationships, [[Nāgārjuna]] uses the latter to "dissolve" the former and deny that there are things. Less obvious is the second stage (Part II), which reverses the analysis: as we shall see, the lack of "thingness" in things implies a way of experiencing in which there is no [[awareness]] of [[cause and effect]]. Things and their [[causal]] relations stand and fall together, because our notion of [[cause-and-effect]] is dependent on that of things, which [[cause]] and are affected. If one collapses, so does the other. The basic problem is that any [[dualism]] between them is untenable. It is the delusive bifurcation between them that [[Nāgārjuna]] is concerned to negate, and the two ways to do this are to use each pole to "deconstruct" the other. Consistent with the general [[Mādhyamika]] project, this is {{Wiki|criticism}} without affirming any [[philosophical]] position: having conflated the [[duality]], [[Nāgārjuna]] does not offer any [[view]] about [[causality]], because [[nothing]] remains to be related to anything else. Part III compares this conclusion with the Advaitic position regarding [[causality]]. | + | This paper will offer one way (perhaps not the only way) of resolving this problem, which may more properly be said to be a [[paradox]]. I shall argue that complete [[conditionality]] is phenomenologically {{Wiki|equivalent}} to a {{Wiki|denial}} of all [[causal]] [[conditions]]. That is, a [[view]] which is so radical as to analyze things away into "their" [[conditions]] is [[offering]] an [[interpretation]] of [[experience]] which becomes indistinguishable from a [[view]] that negates [[causality]] altogether. If this is true, we have another instance where it becomes very difficult to distinguish the [[Mādhyamika]] [[nonduality]] from that of [[Śaṅkara's]] {{Wiki|Advaita Vedānta}}. [6] The argument will be made in two steps. We shall see that there is a [[dialectic]] [[inherent]] in the [[Mādhyamika]] analysis. The first stage (discussed in Part I) is apparent: looking at the {{Wiki|common-sense}} {{Wiki|distinction}} between things and their [[cause-and-effect]] relationships, [[Nāgārjuna]] uses the [[latter]] to "dissolve" the former and deny that there are things. Less obvious is the second stage (Part II), which reverses the analysis: as we shall see, the lack of "thingness" in things implies a way of experiencing in which there is no [[awareness]] of [[cause and effect]]. Things and their [[causal]] relations stand and fall together, because our notion of [[cause-and-effect]] is dependent on that of things, which [[cause]] and are affected. If one collapses, so does the other. The basic problem is that any [[dualism]] between them is untenable. It is the delusive [[bifurcation]] between them that [[Nāgārjuna]] is concerned to negate, and the two ways to do this are to use each pole to "deconstruct" the other. Consistent with the general [[Mādhyamika]] project, this is {{Wiki|criticism}} without [[affirming]] any [[philosophical]] position: having conflated the [[duality]], [[Nāgārjuna]] does not offer any [[view]] about [[causality]], because [[nothing]] remains to be related to anything else. Part III compares this conclusion with the [[Advaitic]] position regarding [[causality]]. |

I | I | ||

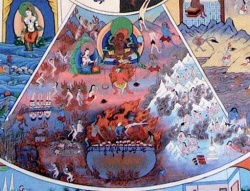

[[File:Gns.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Gns.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | In [[order]] to understand the [[Mādhyamika]] critique, we must begin with a clear [[sense]] of what it is that is [[being]] criticized. This is our {{Wiki|common-sense}} understanding of the [[world]], which sees it as a collection of discrete entities (including myself) interacting [[causally]] "in" {{Wiki|space and time}}. Just as {{Wiki|space and time}}, if they are to [[function]] as "containers," require something understood as nonspatial and nontemporal to "contain," so the [[causal]] relation is normally used to explain the interaction between things which | + | In [[order]] to understand the [[Mādhyamika]] critique, we must begin with a clear [[sense]] of what it is that is [[being]] criticized. This is our {{Wiki|common-sense}} [[understanding]] of the [[world]], which sees it as a collection of discrete entities (including myself) interacting [[causally]] "in" {{Wiki|space and time}}. Just as {{Wiki|space and time}}, if they are to [[function]] as "containers," require something understood as nonspatial and nontemporal to "contain," so the [[causal]] [[relation]] is normally used to explain the interaction between things which |

[5] Sprung,pp. 230, 236. | [5] Sprung,pp. 230, 236. | ||

| − | [6] I have argued for this equivalence in two other papers. "[[Enlightenment in Buddhism]] and {{Wiki|Advaita Vedanta}}: Are [[Nirvāna]] and [[Moksha]] the Same?" International [[Philosophical]] Quarterly, 22 (1982), 65-74, claims that the [[no-self]] modal-view of [[Buddhism]] is indistinguishable from the all-Self substance-view of [[Advaita]]. See my paper "The [[Mahayana]] Deconstruction of [[Time]]" (unpublished) which maintains that the [[nonduality]] between things and [[time]] amounts to making the same claim regarding temporality: if there is only [[time]], this is phenemenologically equivalent to a nunc stans ("[[eternal]] now"). | + | [6] I have argued for this equivalence in two other papers. "[[Enlightenment in Buddhism]] and {{Wiki|Advaita Vedanta}}: Are [[Nirvāna]] and [[Moksha]] the Same?" International [[Philosophical]] Quarterly, 22 (1982), 65-74, claims that the [[no-self]] modal-view of [[Buddhism]] is indistinguishable from the all-Self substance-view of [[Advaita]]. See my paper "The [[Mahayana]] Deconstruction of [[Time]]" (unpublished) which maintains that the [[nonduality]] between things and [[time]] amounts to making the same claim regarding temporality: if there is only [[time]], this is phenemenologically {{Wiki|equivalent}} to a nunc stans ("[[eternal]] now"). |

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

p65 | p65 | ||

| − | are distinct from each other. [[Nāgārjuna]] attacks more than the [[philosophical]] fancies of [[Indian]] metaphysicians, for there is a [[metaphysics]] inherent in our {{Wiki|common-sense}} [[view]]. This {{Wiki|common-sense}} understanding (one or the other aspect of which is absolutized in systematic [[metaphysics]]) is what makes the everyday [[world]] saṁsara for us, and it is this saṁsara that [[Nāgārjuna]] is concerned to "deconstruct." This is why one must beware of making [[Mādhyamika]] into an "ordinary [[language]]" [[philosophy]] by interpreting [[śunyatā]] merely as a "meta-system" term denying a correspondence {{Wiki|theory}} of [[truth]]. By no means does the end of [[philosophical]] language-games "leave everything as it is" for [[Nāgārjuna]], except in the [[sense]] that saṁsara has always really been [[nirvāṇa]]. | + | are {{Wiki|distinct}} from each other. [[Nāgārjuna]] attacks more than the [[philosophical]] fancies of [[Indian]] {{Wiki|metaphysicians}}, for there is a [[metaphysics]] [[inherent]] in our {{Wiki|common-sense}} [[view]]. This {{Wiki|common-sense}} [[understanding]] (one or the other aspect of which is absolutized in systematic [[metaphysics]]) is what makes the everyday [[world]] [[saṁsara]] for us, and it is this [[saṁsara]] that [[Nāgārjuna]] is concerned to "deconstruct." This is why one must beware of making [[Mādhyamika]] into an "ordinary [[language]]" [[philosophy]] by interpreting [[śunyatā]] merely as a "meta-system" term denying a [[correspondence]] {{Wiki|theory}} of [[truth]]. By no means does the end of [[philosophical]] language-games "leave everything as it is" for [[Nāgārjuna]], except in the [[sense]] that [[saṁsara]] has always really been [[nirvāṇa]]. |

[[File:Gold.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Gold.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Why do we [[experience]] the [[world]] as saṁsara, if that is delusive? Why don't we [[experience]] it as it is? The [[traditional]] [[Buddhist]] answer points to [[craving]] and [[ignorance]], but [[Nāgārjuna]] focuses on a particular type of [[mental]] [[attachment]], that which makes all other [[attachment]] possible: [[prapañca]]. The [[nirvāṇa]] chapter of the Kārikās concludes by characterizing [[nirvāṇa]], negatively, as "the coming to rest of all ways of taking things, the [[repose]] of named things (prapañcopaśama)The precise meaning of [[prapañca]] is, unfortunately, unclear. Sprung defines it as "the [[world]] of named things; the [[visible]] manifold." [8] It refers to some {{Wiki|indeterminate}} "interface" between our concepts and our [[perceptions]]: that our categories of [[thinking]] are somehow responsible for our perceiving "the [[visible]] [[world]]" as "manifold." The consequence of [[prapañca]] is that I now perceive the room I am [[writing]] in, not as it really is, nondually, but as a collection of [[books]] and chair and pens and paper. . .and me, each of which is in some {{Wiki|naive}} fashion taken to (1) be distinct from the others and (2) persist unchanged unless affected by something else.[9] | + | Why do we [[experience]] the [[world]] as [[saṁsara]], if that is delusive? Why don't we [[experience]] it as it is? The [[traditional]] [[Buddhist]] answer points to [[craving]] and [[ignorance]], but [[Nāgārjuna]] focuses on a particular type of [[mental]] [[attachment]], that which makes all other [[attachment]] possible: [[prapañca]]. The [[nirvāṇa]] [[chapter]] of the [[Kārikās]] concludes by characterizing [[nirvāṇa]], negatively, as "the coming to rest of all ways of taking things, the [[repose]] of named things (prapañcopaśama)The precise meaning of [[prapañca]] is, unfortunately, unclear. Sprung defines it as "the [[world]] of named things; the [[visible]] manifold." [8] It refers to some {{Wiki|indeterminate}} "interface" between our [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] and our [[perceptions]]: that our categories of [[thinking]] are somehow responsible for our perceiving "the [[visible]] [[world]]" as "manifold." The consequence of [[prapañca]] is that I now {{Wiki|perceive}} the room I am [[writing]] in, not as it really is, nondually, but as a collection of [[books]] and chair and pens and paper. . .and me, each of which is in some {{Wiki|naive}} fashion taken to (1) be {{Wiki|distinct}} from the others and (2) persist unchanged unless affected by something else.[9] |

| − | This point about [[prapañca]] is important because without it one might conclude that [[Nāgārjuna's]] critique of self-existence ([[svabhāva]]) is a refutation of something that no one believes in anyway. But one does not escape his critique by defining entities in a more {{Wiki|common-sense}} fashion as coming-into and passing-out-of [[existence]]. There is no tenable middle ground between self-existence independent of all conditions—an [[empty]] set, for there are no such entities—and the complete conditionality of [[śunyatā]]. The implication of [[Nāgārjuna's]] arguments against self-existence (e.g., MMK chapters I, XV) is to point out the inconsistency in our everyday way of "taking" the [[world]]: we accept that things change, and at the same [[time]] we assume that somehow they also remain the same—which is necessary if there are to be "things" at all. Other [[philosophers]], recognizing this inconsistency, have tried to solve it by absolutizing one of these at the expense of the other; so the satkāryavāda substance-view of {{Wiki|Samkhya}} emphasizes permanence at the price of not being able to account for change, and the asatkāryavāda modal-view of [[early Buddhism]] has the opposite problem of not being able to account for continuity. [[Nāgārjuna]] arranges these and the other solutions that have been proposed into a "[[tetralemma]]" which exhausts the possible [[philosophical]] alternatives; then he proceeds to refute them all. The basic difficulty is that any understanding of [[cause and effect]] which tries to relate two separate things together can be reduced to the contradiction of both asserting and denying identity. Nor can one respond to this simply by denying [[causality]], for that is likewise contradicted by our [[experience]]. So [[Nāgārjuna]] concludes that the "relationship" between [[cause and effect]] is incomprehensible. | + | This point about [[prapañca]] is important because without it one might conclude that [[Nāgārjuna's]] critique of self-existence ([[svabhāva]]) is a refutation of something that no one believes in anyway. But one does not escape his critique by defining entities in a more {{Wiki|common-sense}} fashion as coming-into and passing-out-of [[existence]]. There is no tenable middle ground between self-existence {{Wiki|independent}} of all conditions—an [[empty]] set, for there are no such entities—and the complete [[conditionality]] of [[śunyatā]]. The implication of [[Nāgārjuna's]] arguments against self-existence (e.g., MMK chapters I, XV) is to point out the inconsistency in our everyday way of "taking" the [[world]]: we accept that things change, and at the same [[time]] we assume that somehow they also remain the same—which is necessary if there are to be "things" at all. Other [[philosophers]], [[recognizing]] this inconsistency, have tried to solve it by absolutizing one of these at the expense of the other; so the satkāryavāda substance-view of {{Wiki|Samkhya}} emphasizes [[permanence]] at the price of not being able to account for change, and the asatkāryavāda modal-view of [[early Buddhism]] has the opposite problem of not being able to account for continuity. [[Nāgārjuna]] arranges these and the other solutions that have been proposed into a "[[tetralemma]]" which exhausts the possible [[philosophical]] alternatives; then he proceeds to refute them all. The basic difficulty is that any [[understanding]] of [[cause and effect]] which tries to relate two separate things together can be reduced to the {{Wiki|contradiction}} of both asserting and denying [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]]. Nor can one respond to this simply by denying [[causality]], for that is likewise contradicted by our [[experience]]. So [[Nāgārjuna]] concludes that the "relationship" between [[cause and effect]] is incomprehensible. |

[[File:Goldenbuddha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Goldenbuddha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

[7]''MMKXXV 24, in Sprung p. 264. | [7]''MMKXXV 24, in Sprung p. 264. | ||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

[8]"Ibid., p. 273. | [8]"Ibid., p. 273. | ||

| − | [9] The role of [[prapañca]] in our [[experience]] cannot be fully understood without relating it to our intentions. The relations among [[craving]], [[conceptualizing]], and [[causality]] have been discussed in "The [[Difference]] between saṁsara and [[Nirvāṇa]]," [[Philosophy]] East and West, 33 (1983), 355-365. | + | [9] The role of [[prapañca]] in our [[experience]] cannot be fully understood without relating it to our {{Wiki|intentions}}. The relations among [[craving]], [[conceptualizing]], and [[causality]] have been discussed in "The [[Difference]] between [[saṁsara]] and [[Nirvāṇa]]," [[Philosophy]] [[East]] and [[West]], 33 (1983), 355-365. |

p66 | p66 | ||

| − | But the problem is not resolved simply by criticizing such positions, for the difficulty is fundamentally not abstract and [[philosophical]] but very personal: it is our [[lives]], not just our theories, which are inconsistent in "taking" the [[world]] as a collection of discrete "self-existing" things which yet change. Although during, a [[philosophy]] seminar I may accept the complete conditionality and contingency of all [[experience]], as soon as the seminar ends I {{Wiki|unconsciously}} assume that the colleague I join for lunch is the same [[person]] whom I spoke with before the seminar—although ever-so-slightly different, due to a relatively extraneous change of mood, etc. This constitutes saṁsara because it is by reifying such "thingness" out of the flux of [[experience]] that we become attached to things. (Of course, other hypostatizations of self-existence— my wife, my car and, most of all, myself—tend to be more problematic loci for [[attachment]], but the problem is the same in each case: we [[cling]] to things which dissolve as we try to [[grasp]] them.) | + | But the problem is not resolved simply by criticizing such positions, for the difficulty is fundamentally not abstract and [[philosophical]] but very personal: it is our [[lives]], not just our theories, which are inconsistent in "taking" the [[world]] as a collection of discrete "[[self-existing]]" things which yet change. Although during, a [[philosophy]] seminar I may accept the complete [[conditionality]] and contingency of all [[experience]], as soon as the seminar ends I {{Wiki|unconsciously}} assume that the colleague I join for lunch is the same [[person]] whom I spoke with before the seminar—although ever-so-slightly different, due to a relatively extraneous change of [[mood]], etc. This constitutes [[saṁsara]] because it is by reifying such "thingness" out of the flux of [[experience]] that we become [[attached]] to things. (Of course, other hypostatizations of self-existence— my wife, my car and, most of all, myself—tend to be more problematic loci for [[attachment]], but the problem is the same in each case: we [[cling]] to things which dissolve as we try to [[grasp]] them.) |

| − | It does not suffice to answer this Humean critique of identity [10] with an "ordinary [[language]]" rejoinder that we should become more sensitive to the ways we use our permanence-and-change vocabulary, for the [[Mādhyamika]] position is that our usual everyday [[experience]] is deluded and this ordinary use of [[language]] is deluding. As the first prong of his attack, [[Nāgārjuna]] refutes our {{Wiki|common-sense}} distinction between things and their [[causal]] relations simply by sharpening the distinction to absurdity: if things are to be "self-existent" then they must be separable from their [[conditions]], but their [[existence]] is clearly contingent upon the [[conditions]] that bring them into [[being]] and eventually (when those [[conditions]] no longer operate) [[cause]] them to disappear. If it is objected that one cannot [[live]] without reifying such fictitious entities, at least to some extent, then the [[Mādhyamika]] response is to agree. The "lower [[truth]]", saṁvṛti, is not negated altogether—it is a truth—but it must not be taken as "the higher [[truth]]," as a correct understanding of the way things really are. | + | It does not suffice to answer this Humean critique of [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] [10] with an "ordinary [[language]]" rejoinder that we should become more [[sensitive]] to the ways we use our permanence-and-change vocabulary, for the [[Mādhyamika]] position is that our usual everyday [[experience]] is deluded and this ordinary use of [[language]] is deluding. As the first prong of his attack, [[Nāgārjuna]] refutes our {{Wiki|common-sense}} {{Wiki|distinction}} between things and their [[causal]] relations simply by sharpening the {{Wiki|distinction}} to absurdity: if things are to be "[[self-existent]]" then they must be separable from their [[conditions]], but their [[existence]] is clearly contingent upon the [[conditions]] that bring them into [[being]] and eventually (when those [[conditions]] no longer operate) [[cause]] them to disappear. If it is objected that one cannot [[live]] without reifying such fictitious entities, at least to some extent, then the [[Mādhyamika]] response is to agree. The "lower [[truth]]", saṁvṛti, is not negated altogether—it is a truth—but it must not be taken as "the higher [[truth]]," as a correct [[understanding]] of [[the way things really are]]. |

[[File:GoldenChild JadeOne.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:GoldenChild JadeOne.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | So the first stage of the [[Mādhyamika]] critique uses the complete [[interdependence]] of all things to refute their "thingness." The distinction between things and their [[causal]] relations is negated by adopting the latter as a means to "deconstruct" the former. This completes the early [[Buddhist]] attack on [[substance]]. But this absolutizing of [[conditions]] is only the first step. Now the critique dialectically reverses to use the perspective of the deconstructed thing in [[order]] to deny the [[reality]] of [[causal]] [[conditions]]. In the delusive bifurcation between things and their [[causal]] relations, the category of [[causality]] turns out to be just as dependent on things as things are on their [[causal]] [[conditions]]. Our {{Wiki|concept}} of [[causality]] presupposes a set of discrete entities, whose interrelation we explain as [[causation]]. Cause-and-effect requires something to [[cause]] and something to be effected. If this is so, then a complete conditionality which is so radical that it "dissolves" all things must also dissolve itself. | + | So the first stage of the [[Mādhyamika]] critique uses the complete [[interdependence]] of all things to refute their "thingness." The {{Wiki|distinction}} between things and their [[causal]] relations is negated by adopting the [[latter]] as a means to "deconstruct" the former. This completes the early [[Buddhist]] attack on [[substance]]. But this absolutizing of [[conditions]] is only the first step. Now the critique dialectically reverses to use the {{Wiki|perspective}} of the deconstructed thing in [[order]] to deny the [[reality]] of [[causal]] [[conditions]]. In the delusive [[bifurcation]] between things and their [[causal]] relations, the category of [[causality]] turns out to be just as dependent on things as things are on their [[causal]] [[conditions]]. Our {{Wiki|concept}} of [[causality]] presupposes a set of discrete entities, whose interrelation we explain as [[causation]]. [[Cause-and-effect]] requires something to [[cause]] and something to be effected. If this is so, then a complete [[conditionality]] which is so radical that it "dissolves" all things must also dissolve itself. |

| − | In [[order]] to make this point, it is helpful to transpose the argument from the too-general category of [[causal]] [[conditions]] to the more specific one of motion-and-rest. [[Nāgārjuna]] analyzes motion and rest in chapter two of the Kārikās, immediately after his initial treatment of [[conditions]], and it is clear that the second chapter is meant to apply the general {{Wiki|conclusions}} of chapter one to a particular case. The additional advantage of shifting to motion-and-rest is that we [[illuminate]] what is otherwise a very puzzling chapter. The basic problem is that it is not clear what [[Nāgārjuna]] is actually doing in chapter two. Like Zeno, he denies the [[reality]] of motion, but this is not done | + | In [[order]] to make this point, it is helpful to transpose the argument from the too-general category of [[causal]] [[conditions]] to the more specific one of motion-and-rest. [[Nāgārjuna]] analyzes {{Wiki|motion}} and rest in [[chapter]] two of the [[Kārikās]], immediately after his initial treatment of [[conditions]], and it is clear that the second [[chapter]] is meant to apply the general {{Wiki|conclusions}} of [[chapter]] one to a particular case. The additional advantage of shifting to motion-and-rest is that we [[illuminate]] what is otherwise a very puzzling [[chapter]]. The basic problem is that it is not clear what [[Nāgārjuna]] is actually doing in [[chapter]] two. Like Zeno, he denies the [[reality]] of {{Wiki|motion}}, but this is not done |

| − | [10] See Hume's Enquiry Concerning [[Human]] Understanding, Section IV, Parts I and II. | + | [10] See [[Hume's]] Enquiry Concerning [[Human]] [[Understanding]], Section IV, Parts I and II. |

p67 | p67 | ||

| − | to assert an [[unchanging]] Parmenidean "block-universe," for {{Wiki|Vedantic}} permanence (i.e., "rest") is also denied. As a result, [[Nāgārjuna]] has been criticized for an arid play on words which "resembles the shell game" in [[being]] a [[logical]] sleight-of-hand" [11]— that is, for basing his argument on a subtle distinction between words which are meaningless because they have no [[empirical]] referent—and for committing the [[fallacy]] of composition in arguing that what is true for the parts (in this case, traversed, traversing, and to-be-traversed) must be true for the whole. [12] But I think such criticisms miss the point of [[Nāgārjuna's]] arguments. Their import is that our usual way of understanding motion, which distinguishes the "mover" from "the act of moving," simply does not make [[sense]], because the [[interdependence]] of "mover" and "motion" shows that the {{Wiki|hypostatization}} of either is delusive. (Here "mover" means, not "that which [[causes]] motion", but "that thing which moves"; and "motion" is "the movement that happens to the thing") [[Nāgārjuna's]] [[logic]] in [[stanzas]] two through eleven demonstrates that once we have reified a distinction between them, it becomes impossible to relate them back together again—a quandary familiar to students of the Western {{Wiki|mind-body problem}}, which is the result of another reified bifurcation. The difficulty is shown by isolating this hypostatized mover and inquiring into its status. [[Nāgārjuna]] asks: In itself, is it a mover, or not? That is, is the predicate "moves" intrinsic to this mover, or contingent? The dilemma is that neither way of understanding the situation is satisfactory. If the "mover" in and of itself already moves, then there is no need to add an "act of motion" later; the predication of such a "second motion" would be redundant. But the other alternative—that the "mover" by itself is a non-mover—does not work either because we cannot thereafter add the predicate: it is a contradiction for a non-mover to move. In neither way can we make [[sense]] out of the relation between them. It follows that the "mover" cannot have an [[existence]] of its own apart from the "moving," which means that our usual [[dualistic]] way of understanding motion is untenable. To summarize this in contemporary terms, [[Nāgārjuna]] is pointing out a flaw in the everyday [[language]] we use to describe (and hence our ways of [[thinking]] about) motion: our ascription of motion predicates to substantive [[objects]] is unintelligible. | + | to assert an [[unchanging]] [[Wikipedia:Parmenides|Parmenidean]] "block-universe," for {{Wiki|Vedantic}} [[permanence]] (i.e., "rest") is also denied. As a result, [[Nāgārjuna]] has been criticized for an arid play on words which "resembles the shell game" in [[being]] a [[logical]] sleight-of-hand" [11]— that is, for basing his argument on a {{Wiki|subtle}} {{Wiki|distinction}} between words which are meaningless because they have no [[empirical]] referent—and for committing the [[fallacy]] of composition in arguing that what is true for the parts (in this case, traversed, traversing, and to-be-traversed) must be true for the whole. [12] But I think such {{Wiki|criticisms}} miss the point of [[Nāgārjuna's]] arguments. Their import is that our usual way of [[understanding]] {{Wiki|motion}}, which distinguishes the "mover" from "the act of moving," simply does not make [[sense]], because the [[interdependence]] of "mover" and "{{Wiki|motion}}" shows that the {{Wiki|hypostatization}} of either is delusive. (Here "mover" means, not "that which [[causes]] {{Wiki|motion}}", but "that thing which moves"; and "{{Wiki|motion}}" is "the {{Wiki|movement}} that happens to the thing") [[Nāgārjuna's]] [[logic]] in [[stanzas]] two through eleven demonstrates that once we have reified a {{Wiki|distinction}} between them, it becomes impossible to relate them back together again—a quandary familiar to students of the [[Western]] {{Wiki|mind-body problem}}, which is the result of another reified [[bifurcation]]. The difficulty is shown by isolating this [[Wikipedia:Hypostasis (philosophy and religion)|hypostatized]] mover and inquiring into its {{Wiki|status}}. [[Nāgārjuna]] asks: In itself, is it a mover, or not? That is, is the predicate "moves" intrinsic to this mover, or contingent? The {{Wiki|dilemma}} is that neither way of [[understanding]] the situation is satisfactory. If the "mover" in and of itself already moves, then there is no need to add an "act of {{Wiki|motion}}" later; the predication of such a "second {{Wiki|motion}}" would be redundant. But the other alternative—that the "mover" by itself is a non-mover—does not work either because we cannot thereafter add the predicate: it is a {{Wiki|contradiction}} for a non-mover to move. In neither way can we make [[sense]] out of the [[relation]] between them. It follows that the "mover" cannot have an [[existence]] of its [[own]] apart from the "moving," which means that our usual [[dualistic]] way of [[understanding]] {{Wiki|motion}} is untenable. To summarize this in contemporary terms, [[Nāgārjuna]] is pointing out a flaw in the everyday [[language]] we use to describe (and hence our ways of [[thinking]] about) {{Wiki|motion}}: our ascription of {{Wiki|motion}} predicates to substantive [[objects]] is unintelligible. |

[[File:Graph2.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Graph2.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | At first encounter the above argument may be unconvincing. The options seem so extreme that we suspect there must be some middle ground between them. Of course we can't accept a double movement, but is it really a contradiction for a non-mover to move? What else could move? But, again, no such appeal to our everyday intuitions, or to the ordinary [[language]] which shapes and [[embodies]] them, is successful against the [[Mādhyamika]] critique of those intuitions, which seizes on the inconsistency that is ignored (and to some extent must be ignored) in daily [[life]]. We can elaborate upon this by applying the [[logic]] that was used earlier to deconstruct the [[difference]] between things and their [[causal]] relations. Just as (general rule) complete [[interdependence]] dissolves the thing into its [[rational]] [[conditions]], with no residue of [[substance]] remaining, so (specific case) the [[completeness]] of movement—the fact that no part of "me" stays unmoved in the chair when "I" go to lunch—means that no self-existing and hence [[unchanging]] "thing" remains to move. As with [[time]] and with [[space]], we think of the relation between mover and moving with the {{Wiki|metaphor}} of container and contained, and in all three instances the bifurcation is delusive. In [[order]] to expose the absurdity of this, [[Nāgārjuna]] needs only to sharpen the dichotomy. Despite our intuitions, which | + | At first encounter the above argument may be unconvincing. The options seem so extreme that we suspect there must be some middle ground between them. Of course we can't accept a double {{Wiki|movement}}, but is it really a {{Wiki|contradiction}} for a non-mover to move? What else could move? But, again, no such appeal to our everyday intuitions, or to the ordinary [[language]] which shapes and [[embodies]] them, is successful against the [[Mādhyamika]] critique of those intuitions, which seizes on the inconsistency that is ignored (and to some extent must be ignored) in daily [[life]]. We can elaborate upon this by applying the [[logic]] that was used earlier to deconstruct the [[difference]] between things and their [[causal]] relations. Just as (general {{Wiki|rule}}) complete [[interdependence]] dissolves the thing into its [[rational]] [[conditions]], with no residue of [[substance]] remaining, so (specific case) the [[completeness]] of movement—the fact that no part of "me" stays unmoved in the chair when "I" go to lunch—means that no [[self-existing]] and hence [[unchanging]] "thing" remains to move. As with [[time]] and with [[space]], we think of the [[relation]] between mover and moving with the {{Wiki|metaphor}} of container and contained, and in all three instances the [[bifurcation]] is delusive. In [[order]] to expose the absurdity of this, [[Nāgārjuna]] needs only to sharpen the {{Wiki|dichotomy}}. Despite our intuitions, which |

| − | [11] "Richard Robinson, "Did [[Nāgārjuna]] Really Refute All [[Philosophical]] [[Views]]?" [[Philosophy]] East and West, 22 (1972), 325. | + | [11] "Richard Robinson, "Did [[Nāgārjuna]] Really Refute All [[Philosophical]] [[Views]]?" [[Philosophy]] [[East]] and [[West]], 22 (1972), 325. |

| − | [12] Hsueh-li Cheng, "Motion and Rest in the Middle Treatise," J. of [[Chinese Philosophy]], 1 (1980) 235 ff. | + | [12] Hsueh-li Cheng, "{{Wiki|Motion}} and Rest in the [[Middle Treatise]]," J. of [[Chinese Philosophy]], 1 (1980) 235 ff. |

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

p68 | p68 | ||

| − | inconsistently want to postulate some "[[unchanging]] core" in [[order]] to save the mover, there is no middle ground between a self-existent and hence unmoving thing, and the complete [[dissolution]] of the thing that does the moving. Understood in this way, it becomes obvious why his arguments also work just as well against the intelligibility of rest: the bifurcation between the thing and its [[being]] at rest is just as delusive, and for precisely the same [[reason]]. | + | inconsistently want to postulate some "[[unchanging]] core" in [[order]] to save the mover, there is no middle ground between a [[self-existent]] and hence unmoving thing, and the complete [[dissolution]] of the thing that does the moving. Understood in this way, it becomes obvious why his arguments also work just as well against the intelligibility of rest: the [[bifurcation]] between the thing and its [[being]] at rest is just as delusive, and for precisely the same [[reason]]. |

[[File:Great Departure.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Great Departure.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

II | II | ||

| − | So far, we have effected only the first stage of the [[dialectic]], both in the general analysis of [[causal]] [[conditions]] and this more specific case of motion-and-rest. We have dissolved the thing which moves / is [[caused]] and are left with a changing [[world]] of [[causal]] [[conditions]]. The second stage of the [[dialectic]] is easy to state but harder to understand: granted, if there is only movement, then there is no mover; but if there is [[nothing]] to move, then likewise there can be no movement. Implicit in our {{Wiki|concept}} of change is the notion that a thing is becoming other than it was, so unless one reifies something self-existent (cf. atemporal) in [[order]] to provide continuity between these different [[conditioned]] (temporal) states, there is [[nothing]] outside the changing [[conditions]] to be changed. The {{Wiki|concept}} of change (here a general term to include both conditionality and movement) needs something to "bite" on, but the first stage of the [[dialectic]] leaves [[nothing]] [[unconditioned]] to chew. If the colleague I join for lunch is not in any [[sense]] the same [[person]] I spoke with earlier, because there is no [[substratum]] of permanence to "him," then it makes no [[sense]] to say that "he" has changed. Without a contained, there can be no container; as the bifurcation dissolves, the poles conflate into a whole which, as [[Nāgārjuna]] knew, cannot be represented but remains {{Wiki|philosophically}} {{Wiki|indeterminate}}, since [[language]], in [[order]] to describe at all, must dualize between [[subject]] and predicate, mover and moved, [[cause and effect]]. | + | So far, we have effected only the first stage of the [[dialectic]], both in the general analysis of [[causal]] [[conditions]] and this more specific case of motion-and-rest. We have dissolved the thing which moves / is [[caused]] and are left with a changing [[world]] of [[causal]] [[conditions]]. The second stage of the [[dialectic]] is easy to [[state]] but harder to understand: granted, if there is only {{Wiki|movement}}, then there is no mover; but if there is [[nothing]] to move, then likewise there can be no {{Wiki|movement}}. Implicit in our {{Wiki|concept}} of change is the notion that a thing is becoming other than it was, so unless one reifies something [[self-existent]] (cf. atemporal) in [[order]] to provide continuity between these different [[conditioned]] ({{Wiki|temporal}}) states, there is [[nothing]] outside the changing [[conditions]] to be changed. The {{Wiki|concept}} of change (here a general term to include both [[conditionality]] and {{Wiki|movement}}) needs something to "bite" on, but the first stage of the [[dialectic]] leaves [[nothing]] [[unconditioned]] to chew. If the colleague I join for lunch is not in any [[sense]] the same [[person]] I spoke with earlier, because there is no [[substratum]] of [[permanence]] to "him," then it makes no [[sense]] to say that "he" has changed. Without a contained, there can be no container; as the [[bifurcation]] dissolves, the poles conflate into a whole which, as [[Nāgārjuna]] knew, cannot be represented but remains {{Wiki|philosophically}} {{Wiki|indeterminate}}, since [[language]], in [[order]] to describe at all, must dualize between [[subject]] and predicate, mover and moved, [[cause and effect]]. |

| − | But nonetheless, unless we can get a [[sense]] of what such a way of experiencing would be like, the above argument will be at best {{Wiki|philosophically}} {{Wiki|persuasive}} yet will seem irrelevant to daily [[life]]. What consequences does all this have for the way we actually [[experience]] the [[world]]? In particular, it is still unclear how, except by some "[[logical]] sleight of hand," all-conditionality can be phenomenologically identified with no-conditionality, as we claimed at the beginning of this paper. | + | But nonetheless, unless we can get a [[sense]] of what such a way of experiencing would be like, the above argument will be at best {{Wiki|philosophically}} {{Wiki|persuasive}} yet will seem irrelevant to daily [[life]]. What {{Wiki|consequences}} does all this have for the way we actually [[experience]] the [[world]]? In particular, it is still unclear how, except by some "[[logical]] sleight of hand," all-conditionality can be phenomenologically identified with no-conditionality, as we claimed at the beginning of this paper. |

| − | Let me try to satisfy these questions with the help of a well-known [[Ch'an]] ([[Zen]]) story.[13] The following example discusses the [[causal]] relations of a [[physical]] [[action]], but what is said may be applied just as well to sense-perception (e.g., to the [[nondual]] [[sound]] of a pebble striking {{Wiki|bamboo}}, which [[awakened]] Hsiang-yen, or to the [[nondual]] [[pain]] when Yün-mên broke his ankle) and to [[thought]] (Hui Neng: "If we allow our [[thoughts]], past, present and future, to link up in a series, we put ourselves under restraint. On the other hand, if we never let our [[mind]] attach to anything, we shall gain [[liberation]]."). | + | Let me try to satisfy these questions with the help of a well-known [[Ch'an]] ([[Zen]]) story.[13] The following example discusses the [[causal]] relations of a [[physical]] [[action]], but what is said may be applied just as well to [[sense-perception]] (e.g., to the [[nondual]] [[sound]] of a pebble striking {{Wiki|bamboo}}, which [[awakened]] Hsiang-yen, or to the [[nondual]] [[pain]] when Yün-mên broke his ankle) and to [[thought]] ([[Hui Neng]]: "If we allow our [[thoughts]], {{Wiki|past}}, {{Wiki|present}} and {{Wiki|future}}, to link up in a series, we put ourselves under restraint. On the other hand, if we never let our [[mind]] attach to anything, we shall gain [[liberation]]."). |

[[File:Guides.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Guides.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Lin-chi was a [[monk]] in the [[monastery]] of Huang-po. Three times Lin-chi asked the [[Master]]: "What is the real meaning of [[Bodhidharma]] coming from the West?" and each [[time]] Huang-po immediately struck him. Thereupon, discouraged, he decided to leave | + | [[Lin-chi]] was a [[monk]] in the [[monastery]] of [[Huang-po]]. Three times [[Lin-chi]] asked the [[Master]]: "What is the real meaning of [[Bodhidharma]] coming from the [[West]]?" and each [[time]] [[Huang-po]] immediately struck him. Thereupon, discouraged, he decided to leave |

| − | [13]The direct relevance of [[Ch'an]] [[experience]] to this issue cannot be questioned. While it is true that [[Ch'an]] is not. and does not have, any [[philosophy]], yet it is also the case that [[Mādhyamika]], as a [[philosophical]] exposition of the Prajñāparamīta, may be said to be the [[philosophy]] that most made [[Ch'an]] possible. | + | [13]The direct relevance of [[Ch'an]] [[experience]] to this issue cannot be questioned. While it is true that [[Ch'an]] is not. and does not have, any [[philosophy]], yet it is also the case that [[Mādhyamika]], as a [[philosophical]] [[exposition]] of the Prajñāparamīta, may be said to be the [[philosophy]] that most made [[Ch'an]] possible. |

p69 | p69 | ||

| − | and was advised to go to [[Master]] Ta-yü. Arriving at his [[monastery]], Lin-chi told Ta-yü of his encounters with Huang-po, adding that he didn't [[know]] where he was at fault. | + | and was advised to go to [[Master]] Ta-yü. Arriving at his [[monastery]], [[Lin-chi]] told Ta-yü of his encounters with [[Huang-po]], adding that he didn't [[know]] where he was at fault. |

| − | [[Master]] Ta-yü exclaimed; "Your [[master]] treated you entirely with grandmotherly [[kindness]], and yet you say you don't [[know]] your fault." [[Hearing]] this, Lin-chi was suddenly [[awakened]] and said; "After all, there isn't much in Huang-po's [[Buddhism]]!" [14] | + | [[Master]] Ta-yü exclaimed; "Your [[master]] treated you entirely with grandmotherly [[kindness]], and yet you say you don't [[know]] your fault." [[Hearing]] this, [[Lin-chi]] was suddenly [[awakened]] and said; "After all, there isn't much in Huang-po's [[Buddhism]]!" [14] |

| − | What did Lin-chi realize that [[awakened]] him? If (rushing in where [[Ch'an]] [[masters]] will not tread) we distort his [[experience]] into an [[idea]] in [[order]] to gloss this story, we may say that Lin-chi must have [[realized]] that Huang-po had been answering his question. The blows he received were not punishment but a demonstration of why [[Bodhidharma]] came from the West. On the {{Wiki|common-sense}} level, the answer to Lin-chi's question is obvious: [[Bodhidharma]] was bringing [[Buddhism]] to [[China]]. But this is a [[relative]], "lower [[truth]]" explanation. As a standard [[Ch'an]] question designed to initiate a dialogue, it goes without saying that what is sought is the "higher [[truth]]," and on this level there is no "why." For the [[enlightened]] [[person]], each [[experience]] is complete in itself, the only thing in the whole [[universe]]; for each [[action]] is [[tathata]]. [[Nothing]] changes because without prapañca-reification everything is [[perceived]] afresh, for the first [[time]]. As [[Bodhidharma]] walked from [[India]] there was no [[thought]] of "why" in his head; "he" was each step. In the same way, there was no "why" to Huang-po's blows; "he" was that spontaneous, unselfconscious [[action]]. Lin-chi's sudden [[realization]] of this overflowed into his exclamation: "So, there isn't much to [[Buddhism]] after all!" (Only "just 'this'!") Upon returning to Huang-po, he revealed the depth of his understanding—more than just an [[intellectual]] insight—by not hesitating to give Huang-po a dose of his own [[medicine]]. | + | What did [[Lin-chi]] realize that [[awakened]] him? If (rushing in where [[Ch'an]] [[masters]] will not tread) we distort his [[experience]] into an [[idea]] in [[order]] to gloss this story, we may say that [[Lin-chi]] must have [[realized]] that [[Huang-po]] had been answering his question. The blows he received were not {{Wiki|punishment}} but a demonstration of why [[Bodhidharma]] came from the [[West]]. On the {{Wiki|common-sense}} level, the answer to Lin-chi's question is obvious: [[Bodhidharma]] was bringing [[Buddhism]] to [[China]]. But this is a [[relative]], "lower [[truth]]" explanation. As a standard [[Ch'an]] question designed to initiate a {{Wiki|dialogue}}, it goes without saying that what is sought is the "higher [[truth]]," and on this level there is no "why." For the [[enlightened]] [[person]], each [[experience]] is complete in itself, the only thing in the whole [[universe]]; for each [[action]] is [[tathata]]. [[Nothing]] changes because without prapañca-reification everything is [[perceived]] afresh, for the first [[time]]. As [[Bodhidharma]] walked from [[India]] there was no [[thought]] of "why" in his head; "he" was each step. In the same way, there was no "why" to Huang-po's blows; "he" was that spontaneous, unselfconscious [[action]]. Lin-chi's sudden [[realization]] of this overflowed into his exclamation: "So, there isn't much to [[Buddhism]] after all!" (Only "just 'this'!") Upon returning to [[Huang-po]], he revealed the depth of his understanding—more than just an [[intellectual]] insight—by not hesitating to give [[Huang-po]] a dose of his [[own]] [[medicine]]. |

[[File:H1qh.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:H1qh.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The [[paradox]] which makes the above story relevant to this paper is the fact that, at the same [[time]], Bodhidharma's and Huang-po's [[actions]] are intentional. Huang-po's blow may be immediate and spontaneous, but there is also a "[[reason]]" for it; it is not a random or irrelevant gesture, but a very appropriate response to that particular question, drawn forth by that situation. If we translate this point about {{Wiki|intention}} back into our more general category of [[causality]], here we have a case of an act which is both completely [[caused]] (perfect [[upāya]]: glove fitting hand tightly, to use the [[Ch'an]] analogy) and yet is also uncaused. This [[paradox]] is a contradiction only according to our usual understanding of [[causality]], which uses that category-of-thought to relate together the supposedly discrete [[objects]] into which [[prapañca]] carves the [[world]]. The first and most important of these hypostatized "things" is me, the subject who craves some of these [[objects]] and thus needs an understanding of [[cause-and-effect]] relationships in [[order]] to manipulate circumstances and obtain them. (It has been argued that the [[desire]] for such manipulation is the very [[root]] of our {{Wiki|concept}} of [[causality]]. [15] ) This would apply to the story in question if Huang-po, prapañca-deluded, were to perceive Lin-chi dualistically: Lin-chi is sitting there, a person-object that needs to be [[enlightened]], and I, | + | The [[paradox]] which makes the above story relevant to this paper is the fact that, at the same [[time]], [[Bodhidharma's]] and Huang-po's [[actions]] are intentional. Huang-po's blow may be immediate and spontaneous, but there is also a "[[reason]]" for it; it is not a random or irrelevant gesture, but a very appropriate response to that particular question, drawn forth by that situation. If we translate this point about {{Wiki|intention}} back into our more general category of [[causality]], here we have a case of an act which is both completely [[caused]] ({{Wiki|perfect}} [[upāya]]: glove fitting hand tightly, to use the [[Ch'an]] analogy) and yet is also uncaused. This [[paradox]] is a {{Wiki|contradiction}} only according to our usual [[understanding]] of [[causality]], which uses that category-of-thought to relate together the supposedly discrete [[objects]] into which [[prapañca]] carves the [[world]]. The first and most important of these [[Wikipedia:Hypostasis (philosophy and religion)|hypostatized]] "things" is me, the [[subject]] who craves some of these [[objects]] and thus needs an [[understanding]] of [[cause-and-effect]] relationships in [[order]] to {{Wiki|manipulate}} circumstances and obtain them. (It has been argued that the [[desire]] for such manipulation is the very [[root]] of our {{Wiki|concept}} of [[causality]]. [15] ) This would apply to the story in question if [[Huang-po]], prapañca-deluded, were to {{Wiki|perceive}} [[Lin-chi]] [[dualistically]]: [[Lin-chi]] is sitting there, a person-object that needs to be [[enlightened]], and I, |

| − | [14] This version of the story, from the [[Transmission]] of the [[Lamp]], is given in Chang Chung-yuan, Original Teachings of [[Ch'an]] [[Buddhism]] ({{Wiki|New York}}; Vintage, 1971), pp. 116-17. | + | [14] This version of the story, from the [[Transmission]] of the [[Lamp]], is given in [[Chang]] Chung-yuan, Original Teachings of [[Ch'an]] [[Buddhism]] ({{Wiki|New York}}; Vintage, 1971), pp. 116-17. |

| − | [15] The [[idea]] of [[cause]] has its [[roots]] in purposive [[activity]] and is employed in the first instance when we are concerned to produce or to prevent something. To discover the [[cause]] of something is to discover what has to be attested by our [[activity]] in [[order]] to produce or to prevent that thing; but once the [[word]] '[[cause]]' comes to be applied to natural events, the notion of altering the course of events lends to be dropped. '[[Cause]]' is then used in a nonpractical, purely diagnostic way in cases where we have no interest in altering events or [[power]] to alter them." (P. H. Nowell-Smith, "[[Causality]] or [[Causation]]." I have a cyclostyled copy of this article but have not been able to trace its source.) | + | [15] The [[idea]] of [[cause]] has its [[roots]] in purposive [[activity]] and is employed in the first instance when we are concerned to produce or to prevent something. To discover the [[cause]] of something is to discover what has to be attested by our [[activity]] in [[order]] to produce or to prevent that thing; but once the [[word]] '[[cause]]' comes to be applied to natural events, the notion of altering the course of events lends to be dropped. '[[Cause]]' is then used in a nonpractical, purely {{Wiki|diagnostic}} way in cases where we have no [[interest]] in altering events or [[power]] to alter them." (P. H. Nowell-Smith, "[[Causality]] or [[Causation]]." I have a cyclostyled copy of this article but have not been able to trace its source.) |

p70 | p70 | ||

| − | Huang-po sitting here, am the [[person]] who will try to [[enlighten]] him. Then "my" blow is reified into a deliberated effect which I hope will [[cause]] Lin-chi's [[awakening]]. | + | [[Huang-po]] sitting here, am the [[person]] who will try to [[enlighten]] him. Then "my" blow is reified into a deliberated effect which I {{Wiki|hope}} will [[cause]] Lin-chi's [[awakening]]. |

[[File:Ha1r.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Ha1r.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | But if, as all schools of [[Buddhism]] agree, there is no [[self]] to do this causal-relating-between-things, then the above understanding of the situation must be delusive. So Huang-po must have [[experienced]] it differently, and [[causality]] too must be understood differently. It is not denied: on the contrary, without the [[sense]] of [[self]] and other [[prapañca]]- reified [[objects]] as a counterfoil, it expands to include everything, as Nagar-juna has already shown. (So the [[doctrine]] of [[karma]] can be understood simply by applying something like Newton's third law of [[physical]] motion to the [[mental]] [[realm]] as well.) From the perspective of Mādhyamika's "all-conditionality" which deconstructs all things, Huang-po's blow is part of a seamless web of [[conditions]] which can be extended, as Hwa Yen does, to encompass the entire [[universe]]. As one [[jewel]] in the [[infinite]] web of lndra, the blow reflects everything everywhere, at all times. But if every event that happens is interdependent with everything else in the whole [[universe]], what a different way of experiencing this involves! It suggests a Spinozistic acceptance of whatever happens, as a product of the whole, but more than this it implies the irrelevance of [[causality]] as usually understood. "All-conditionality," in its complete {{Wiki|negation}} of anything to be attached to, offers no practical utility, because there is no longer any [[object]] to be obtained or any [[self]] that craves it; whereas a [[self]] that wants to obtain some thing will need to isolate some discrete [[object]] or [[action]] as the [[cause]] which leads to obtaining it. | + | But if, as all schools of [[Buddhism]] agree, there is no [[self]] to do this causal-relating-between-things, then the above [[understanding]] of the situation must be delusive. So [[Huang-po]] must have [[experienced]] it differently, and [[causality]] too must be understood differently. It is not denied: on the contrary, without the [[sense]] of [[self]] and other [[prapañca]]- reified [[objects]] as a counterfoil, it expands to include everything, as Nagar-juna has already shown. (So the [[doctrine]] of [[karma]] can be understood simply by applying something like Newton's third law of [[physical]] {{Wiki|motion}} to the [[mental]] [[realm]] as well.) From the {{Wiki|perspective}} of [[Mādhyamika's]] "all-conditionality" which deconstructs all things, Huang-po's blow is part of a seamless web of [[conditions]] which can be extended, as [[Hwa Yen]] does, to encompass the entire [[universe]]. As one [[jewel]] in the [[infinite]] web of lndra, the blow reflects everything everywhere, at all times. But if every event that happens is [[interdependent]] with everything else in the whole [[universe]], what a different way of experiencing this involves! It suggests a Spinozistic [[acceptance]] of whatever happens, as a product of the whole, but more than this it implies the irrelevance of [[causality]] as usually understood. "All-conditionality," in its complete {{Wiki|negation}} of anything to be [[attached]] to, offers no {{Wiki|practical}} utility, because there is no longer any [[object]] to be obtained or any [[self]] that craves it; whereas a [[self]] that wants to obtain some thing will need to isolate some discrete [[object]] or [[action]] as the [[cause]] which leads to obtaining it. |

| − | What does all this imply about the way Huang-po [[experienced]] his own [[action]]? Because he did not perceive the situation dualistically, the [[action]] was not "his." That the blow was appropriate to the situation was not due to any prior {{Wiki|deliberation}}, however quick. On the contrary, the [[action]] was so appropriate precisely because it was not deliberated, just as the best responses in "dharma-combat" are unmediated by any self-conscious "[[hindrance]] in the [[mind]]." Then why did Huang-po strike, rather than shout "ho!" as Ma-tsu often did, or utter a few soft words, as Chao-chou probably would have done? This is the crucial point: He does not [[know]] and cannot [[know]]. ("Not-knowing is very profound" said [[Master]] Lo-han, precipitating Wên-i's [[awakening]].) His spontaneous [[actions]] are traceless, "like the tracks of a bird in the sky." [16] They respond to a situation like a glove fits on a hand because whatever "decisions are made" (if this phrase can be used here) are not made by him. If one nondualistically is the [[cause]] (or effect, or both), rather than [[being]] a hypostatized [[self]] that dualistically uses it, then there is not the [[awareness]] that it is a [[cause]] (or effect, or both); it is [[experienced]] as whole, complete, and "traceless." In this way there turn out to be only two alternatives: either [[cause-and-effect]] relationships between discrete prapañca-objects, manipulated by the prapañca-subject, or [[nondual]] "all-conditionality" which amounts to an [[experience]] of complete [[unconditioned]] freedom. Without the interference that the [[self]] creates, Indra's all-encompassing web of [[causal]] [[conditions]] is indeed seamless. In [[psychological]] terms, the barrier between [[consciousness]] ("[[ego]]") and subconsciousness dissolves ("the bottom falls out of the bucket") and thereafter [[thoughts]] and [[actions]] are [[experienced]] as welling-up nondually from a source | + | What does all this imply about the way [[Huang-po]] [[experienced]] his [[own]] [[action]]? Because he did not {{Wiki|perceive}} the situation [[dualistically]], the [[action]] was not "his." That the blow was appropriate to the situation was not due to any prior {{Wiki|deliberation}}, however quick. On the contrary, the [[action]] was so appropriate precisely because it was not deliberated, just as the best responses in "dharma-combat" are unmediated by any self-conscious "[[hindrance]] in the [[mind]]." Then why did [[Huang-po]] strike, rather than shout "ho!" as [[Ma-tsu]] often did, or utter a few soft words, as [[Chao-chou]] probably would have done? This is the crucial point: He does not [[know]] and cannot [[know]]. ("Not-knowing is very profound" said [[Master]] Lo-han, precipitating Wên-i's [[awakening]].) His spontaneous [[actions]] are traceless, "like the tracks of a bird in the sky." [16] They respond to a situation like a glove fits on a hand because whatever "decisions are made" (if this [[phrase]] can be used here) are not made by him. If one nondualistically is the [[cause]] (or effect, or both), rather than [[being]] a [[Wikipedia:Hypostasis (philosophy and religion)|hypostatized]] [[self]] that [[dualistically]] uses it, then there is not the [[awareness]] that it is a [[cause]] (or effect, or both); it is [[experienced]] as whole, complete, and "traceless." In this way there turn out to be only two alternatives: either [[cause-and-effect]] relationships between discrete prapañca-objects, manipulated by the prapañca-subject, or [[nondual]] "all-conditionality" which amounts to an [[experience]] of complete [[unconditioned]] freedom. Without the interference that the [[self]] creates, [[Indra's]] all-encompassing web of [[causal]] [[conditions]] is indeed seamless. In [[psychological]] terms, the barrier between [[consciousness]] ("[[ego]]") and [[subconsciousness]] dissolves ("the bottom falls out of the bucket") and thereafter [[thoughts]] and [[actions]] are [[experienced]] as welling-up nondually from a source |

[[File:Hell re.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Hell re.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [16] Tung-shan told his students to walk "in the bird's track," which is of course trackless, having no deliberative traces before ("Should I do this or that?") and leaving none after ("Should I have done that?"). For further [[discussion]] of the relations among [[action]], {{Wiki|intention}}, and [[nonduality]], see "Wei-wu-wei: [[Nondual]] [[Action]]," [[Philosophy]] East and West, 35 (Jan. 1985). | + | [16] [[Tung-shan]] told his students to walk "in the bird's track," which is of course trackless, having no deliberative traces before ("Should I do this or that?") and leaving none after ("Should I have done that?"). For further [[discussion]] of the relations among [[action]], {{Wiki|intention}}, and [[nonduality]], see "Wei-wu-wei: [[Nondual]] [[Action]]," [[Philosophy]] [[East]] and [[West]], 35 (Jan. 1985). |

p71 | p71 | ||

| Line 129: | Line 129: | ||

III | III | ||

| − | At first glance, the Advaitic account of [[causality]] is very different from the [[Mādhyamika]] {{Wiki|conclusions}} and [[Ch'an]] [[experience]] which have been discussed above. Śaṅkara's position regarding [[causality]] constitutes part of his more general [[māyā]] [[doctrine]], according to which all [[phenomena]] are the indescribable and indefinable ajñana which is superimposed (adhyāsa) upon [[Brahman]]. But if we delve beneath the surface of {{Wiki|terminology}} and ask what [[experience]] this describes, it becomes difficult to find any {{Wiki|phenomenological}} basis for the distinction between the [[Mādhyamika]] and Advaitic accounts. | + | At first glance, the [[Advaitic]] account of [[causality]] is very different from the [[Mādhyamika]] {{Wiki|conclusions}} and [[Ch'an]] [[experience]] which have been discussed above. [[Śaṅkara's]] position regarding [[causality]] constitutes part of his more general [[māyā]] [[doctrine]], according to which all [[phenomena]] are the [[indescribable]] and indefinable ajñana which is {{Wiki|superimposed}} (adhyāsa) upon [[Brahman]]. But if we delve beneath the surface of {{Wiki|terminology}} and ask what [[experience]] this describes, it becomes difficult to find any {{Wiki|phenomenological}} basis for the {{Wiki|distinction}} between the [[Mādhyamika]] and [[Advaitic]] accounts. |

| − | Perhaps this similarity should not be surprising, since Śaṅkara's [[dialectic]] was clearly influenced by [[Nāgārjuna's]]. In this regard, it is relevant to compare Śaṅkara's careful critique of [[Vijñānavāda]] with his cursory dismissal of Śunyavāda as nihilistic and unworthy of repudiation. [18] Śaṅkara's main treatment of [[causality]], in Brahma-Sūtra-Bhāsya II.i.14-20, is indebted to the [[Mādhyamika]] [[dialectic]] and reaches a similar conclusion, that we cannot derive the real nature of [[causal]] relations from the series of discrete [[cause-and-effect]] [[phenomena]]. As a Vedantin, Śaṅkara then leaps to the conclusion that the true [[cause]] of all effects must be [[Brahman]], which provides the permanent [[substratum]] that persists unchanged through all [[experience]]. All effect-phenomena are merely [[illusory]] name-and-form superimpositions upon [[Brahman]], the substance-ground. Since [[Brahman]] is the only real ([[svabhāva]]), and [[phenomena]] [[existing]] as distinct from it are [[illusory]], this is a version of satkāryavāda: the effect pre-exists in the [[cause]]. But to distinguish this [[view]] from that of Sāṁkhya, which identifies [[cause and effect]] by granting the [[reality]] of [[prakṛti]], Śaṅkara's {{Wiki|theory}} of [[causality]] is more precisely labelled vivartavāda, since the effect ([[māyā]]) has a different kind of [[being]] from the [[cause]] ([[Brahman]]). [19] | + | Perhaps this similarity should not be surprising, since [[Śaṅkara's]] [[dialectic]] was clearly influenced by [[Nāgārjuna's]]. In this regard, it is relevant to compare [[Śaṅkara's]] careful critique of [[Vijñānavāda]] with his cursory dismissal of Śunyavāda as [[Wikipedia:Nihilism|nihilistic]] and unworthy of repudiation. [18] [[Śaṅkara's]] main treatment of [[causality]], in Brahma-Sūtra-Bhāsya II.i.14-20, is indebted to the [[Mādhyamika]] [[dialectic]] and reaches a similar conclusion, that we cannot derive the real [[nature]] of [[causal]] relations from the series of discrete [[cause-and-effect]] [[phenomena]]. As a [[Vedantin]], [[Śaṅkara]] then leaps to the conclusion that the true [[cause]] of all effects must be [[Brahman]], which provides the [[permanent]] [[substratum]] that persists unchanged through all [[experience]]. All effect-phenomena are merely [[illusory]] name-and-form superimpositions upon [[Brahman]], the substance-ground. Since [[Brahman]] is the only real ([[svabhāva]]), and [[phenomena]] [[existing]] as {{Wiki|distinct}} from it are [[illusory]], this is a version of satkāryavāda: the effect pre-exists in the [[cause]]. But to distinguish this [[view]] from that of [[Sāṁkhya]], which identifies [[cause and effect]] by granting the [[reality]] of [[prakṛti]], [[Śaṅkara's]] {{Wiki|theory}} of [[causality]] is more precisely labelled vivartavāda, since the effect ([[māyā]]) has a different kind of [[being]] from the [[cause]] ([[Brahman]]). [19] |

[[File:Hism1.jpeg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Hism1.jpeg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Expressed in this way, the [[views]] of [[Nāgārjuna]] and Śaṅkara seem diametrically op- | + | Expressed in this way, the [[views]] of [[Nāgārjuna]] and [[Śaṅkara]] seem diametrically op- |

| − | [17] This [[view]] of [[Mādhyamika]] is important for understanding the [[trisvabhāva]] [[doctrine]] of [[Yogācāra]] [[Buddhism]]. The [[prapañca]] [[world]] of discrete [[forms]] corresponds to parikalpita-svabhāva, the "[[imagined]] nature." "All-conditionality" corresponds to parinispanna-svabhāva, the "other-dependent nature." "No-conditionality" corresponds to parinispanna-svabhāva, the absolutely-accomplished [[nondual]] nature. Read in this way, [[Vasubandhu's]] Trisvabhāvanirdeśa, for example, is completely consistent with the [[Mādhyamika]] analysis of [[experience]]. For both [[Mādhyamika]] and [[Yogācāra]], an understanding of "all-conditionality," with its {{Wiki|negation}} of the self-existence of discrete things, is the crucial "hinge" by which we turn from [[avidyā]] to [[prajña]]. | + | [17] This [[view]] of [[Mādhyamika]] is important for [[understanding]] the [[trisvabhāva]] [[doctrine]] of [[Yogācāra]] [[Buddhism]]. The [[prapañca]] [[world]] of discrete [[forms]] corresponds to [[parikalpita-svabhāva]], the "[[imagined]] [[nature]]." "All-conditionality" corresponds to parinispanna-svabhāva, the "[[other-dependent]] [[nature]]." "No-conditionality" corresponds to parinispanna-svabhāva, the absolutely-accomplished [[nondual]] [[nature]]. Read in this way, [[Vasubandhu's]] [[Trisvabhāvanirdeśa]], for example, is completely consistent with the [[Mādhyamika]] analysis of [[experience]]. For both [[Mādhyamika]] and [[Yogācāra]], an [[understanding]] of "all-conditionality," with its {{Wiki|negation}} of the self-existence of discrete things, is the crucial "hinge" by which we turn from [[avidyā]] to [[prajña]]. |

| − | I think that the [[Mādhyamika]] [[view]] of causality—a [[dialectic]] which equates complete conditionality with no-conditionality—also implies a critique of Derrida's deconstruction. Derrida's use of the open-endedness (différance) of texts to deconstruct the self-as-writer employs only the First movement of the [[dialectic]]; the second and reverse movement (which Derrida does not make) uses the lack of a [[self]] to deconstruct the dissemination of meaning. One ends up with something more like the presence of the late Heidegger, where [[language]] is [[realized]] to be "the house of [[Being]]." The same point can be made by comparing the [[Mādhyamika]] critique of temporal relations with Derrida's critique of "logocentrism." | + | I think that the [[Mādhyamika]] [[view]] of causality—a [[dialectic]] which equates complete [[conditionality]] with no-conditionality—also implies a critique of Derrida's deconstruction. Derrida's use of the open-endedness (différance) of texts to deconstruct the self-as-writer employs only the First {{Wiki|movement}} of the [[dialectic]]; the second and reverse {{Wiki|movement}} (which [[Derrida]] does not make) uses the lack of a [[self]] to deconstruct the dissemination of meaning. One ends up with something more like the presence of the late [[Wikipedia:Martin Heidegger|Heidegger]], where [[language]] is [[realized]] to be "the house of [[Being]]." The same point can be made by comparing the [[Mādhyamika]] critique of {{Wiki|temporal}} relations with Derrida's critique of "logocentrism." |

| − | [18] It is not unlikely that Śankara discovered his own [[non-dual]] [[philosophy]] in the system of [[Nāgārjuna]] and left it unexplained. His debt to Śunyata [[doctrine]] was so great that he quietly passed over it." Lal Mani Joshi, Studies in the [[Buddhistic]] Culture of [[India]] (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1977), p. 234. | + | [18] It is not unlikely that Śankara discovered his [[own]] [[non-dual]] [[philosophy]] in the system of [[Nāgārjuna]] and left it unexplained. His debt to [[Śunyata]] [[doctrine]] was so great that he quietly passed over it." Lal Mani Joshi, Studies in the [[Buddhistic]] {{Wiki|Culture}} of [[India]] ({{Wiki|Delhi}}: {{Wiki|Motilal Banarsidass}}, 1977), p. 234. |

[19] Compare William Blake: "And every Natural Effect has a [[Spiritual]] [[Cause]], and Not a Natural; for a Natural [[Cause]] only seems: it is a [[delusion]]. .. ." (Milton, plate 28, 44-45) | [19] Compare William Blake: "And every Natural Effect has a [[Spiritual]] [[Cause]], and Not a Natural; for a Natural [[Cause]] only seems: it is a [[delusion]]. .. ." (Milton, plate 28, 44-45) | ||

| Line 145: | Line 145: | ||

p72 | p72 | ||