The Symbolism of Rabbits and Hares by Terri Windling

A medieval church stands at the center of my small village in England’s West Country, and in that church is a strange little carving that has come to be known as the symbol of our town: three hares in a circle, their interlinked ears forming a perfect triangle.

Known locally as the Tinner Rabbits, the design was widely believed to be based on an old alchemical symbol for tin, representing the historic importance of tin mining on Dartmoor nearby.

Recently, however, a group of local artists and historians created the Three Hares Project to investigate the symbol’s history.

To their surprise, they discovered that the design’s famous tin association is actually a dubious one, deriving from a misunderstanding of an alchemical illustration published in the early 17th century.

In fact, the symbol is much older and farther ranging than early folklorists suspected.

It is, the Three Hares Project reports, "an extraordinary and ancient archetype, stretching across diverse religions and cultures, many centuries and many thousands of miles.

It is part of the shared medieval heritage of Europe and Asia (Buddhism, Islam, Christianity and Judaism) yet still inspires creative work among contemporary artists."

The earliest known examples of the design can be found in Buddhist cave temples in China (581-618 CE); from there it spread all along the Silk Road, through the Middle East, through Hungary and Poland to Germany, Switzerland, and the British Isles.

Though now associated with the Holy Trinity in Christian iconography, the original, pre-Christian meaning of the Three Hares design has yet to be discovered.

We can glimpse possible interpretations, however, by examing the wealth of world mythology and folklore involving rabbits and hares.

In many mythic traditions, these animals were archetypal symbols of femininity, associated with the lunar cycle, fertility, longevity, and rebirth.

But if we dig a little deeper into their stories we find that they are also contradictory, paradoxical creatures: symbols of both cleverness and foolishness, of femininity and androgyny, of cowardice and courage, of rampant sexuality and virginal purity.

In some lands, Hare is the messenger of the Great Goddess, moving by moonlight between the human world and the realm of the gods; in other lands he is a god himself, wily deceiver and sacred world creator rolled into one.

The association of rabbits, hares, and the moon can be found in numerous cultures the world over — ranging from Japan to Mexico, from Indonesia to the British Isles.

Whereas in Western folklore we refer to the "Man in the Moon," the "Hare (or Rabbit) in the Moon" is a more familiar symbol in other societies.

In China, for example, the Hare in the Moon is depicted with a mortar and pestle in which he mixes the elixir of immortality; he is the messenger of a female moon deity and the guardian of all wild animals.

In Chinese folklore, female hares conceive through the touch of the full moon's light (without the need of impregnation by the male), or by crossing water by moonlight, or licking moonlight from a male hare’s fur.

Figures of hares or white rabbits are commonly found at Chinese Moon Festivals, where they represent longevity, fertility, and the feminine power of yin.

In one old Chinese legend, Buddha summoned the animals to him before he departed from the earth, but only twelve representatives of the animal kingdom came to bid him farewell.

He rewarded these twelve by naming a year after each one, in repeating cycles through eternity.

The animal ruling the year in which a child born is the animal "hiding in the heart," casting a strong influence on personality, spirit, and fate.

Rabbit was the fourth animal to arrive, and thus rules over the calendar in the fourth year of every twelve.

People born into the Year of the Rabbit are said to be intelligent, intuitive, gracious, kind, loyal, sensitive to beauty, diplomatic and peace-loving, but prone to moodiness and periods of melancholy.

In another Buddhist legend, from India this time, Lord Buddha was a hare in an early incarnation, traveling in the company of an ape and a fox.

The god Indra, disguised as a hungry beggar, decided to test their hospitality.

Each animal went in search of food, and only the hare returned empty handed.

Determined to be hospitable, the hare built a fire and jumped into it himself, feeding Indra with his own flesh.

The god rewarded this sacrifice by transforming him into the Hare in the Moon.

In Egyptian myth, hares were also closely associated with the cycles of the moon, which was viewed as masculine when waxing and feminine when waning.

Hares were likewise believed to be androgynous, shifting back and forth between the genders—not only in ancient Egypt but also in European folklore right up to the 18th century.

A hare-headed god and goddess can be seen on the Egyptian temple walls of Dendera,

where the female is believed to be the goddess Unut (or Wenet), while the male is most likely a representation of Osiris (also called Wepuat or Un-nefer), who was sacrificed to the Nile annually in the form of a hare.

In Greco-Roman myth, the hare represented romantic love, lust, abundance, and fercundity.

Pliny the Elder recommended the meat of the hare as a cure for sterility, and wrote that a meal of hare enhanced sexual attraction for a period of nine days.

Hares were associated with the Artemis, goddess of wild places and the hunt, and newborn hares were not to be killed but left to her protection.

Rabbits were sacred to Aphrodite, the goddess of love, beauty, and marriage—for rabbits had “the gift of Aphrodite” (fertility) in great abundance. In Greece, the gift of a rabbit was a common love token from a man to his male or female lover.

In Rome, the gift of a rabbit was intended to help a barren wife conceive. Carvings of rabbits eating grapes and figs appear on both Greek and Roman tombs, where they symbolize the transformative cycle of life, death, and rebirth.

In Teutonic myth, the earth and sky goddess Holda, leader of the Wild Hunt, was followed by a procession of hares bearing torches.

Although she descended into a witch–like figure and boogeyman of children’s tales, she was once revered as a beautiful, powerful goddess in charge of weather phenomena.

Freyja, the headstrong Norse goddess of love, sensuality, and women’s mysteries, was also served by hare attendants. She traveled with a sacred hare and boar in a chariot drawn by cats.

Kaltes, the shape–shifting moon goddess of western Siberia, liked to roam the hills in the form of a hare, and was sometimes pictured in human shape wearing a headdress with hare’s ears.

Ostara, the goddess of the moon, fertility, and spring in Anglo–Saxon myth, was often depicted with a hare’s head or ears, and with a white hare standing in attendance.

This magical white hare laid brightly colored eggs which were given out to children during spring fertility festivals — an ancient tradition that survives in the form of the Easter Bunny today.

Eostre, the Celtic version of Ostara, was a goddess also associated with the moon, and with mythic stories of death, redemption, and resurrection during the turning of winter to spring. Eostre, too, was a shape–shifter, taking the shape of a hare at each full moon; all hares were sacred to her, and acted as her messengers. Cesaer recorded that rabbits and hares were taboo foods to the Celtic tribes.

In Ireland, it was said that eating a hare was like eating one’s own grandmother — perhaps due to the sacred connection between hares and various goddesses, warrior queens, and female faeries, or else due to the belief that old "wise women" could shape–shift into hares by moonlight.

The Celts used rabbits and hares for divination and other shamanic practices by studying the patterns of their tracks, the rituals of their mating dances, and mystic signs within their entrails.

It was believed that rabbits burrowed underground in order to better commune with the spirit world, and that they could carry messages from the living to the dead and from humankind to the faeries.

As Christianity took hold in western Europe, hares and rabbits, so firmly associated with the Goddess, came to be seen in a less favorable light — viewed suspiciously as the familiars of witches, or as witches themselves in animal form.

Numerous folk tales tell of men led astray by hares who are really witches in disguise, or of old women revealed as witches when they are wounded in their animal shape. In one well–known story from Dartmoor, a mighty hunter named Bowerman disturbed a coven of witches practicing their rites, and so one young witch determined to take revenge upon the man.

She shape–shifted into a hare, led Bowerman through a deadly bog, then turned the hunter and his hounds into piles of stones, which can still be seen today. (The stone formations are known by the names Hound Tor and Bowerman’s Nose.)

Although rabbits, in the Christian era, were still sometimes known as good luck symbols (hence the tradition of carrying a "lucky rabbit’s foot"), they also came to be seen as witch–associated portents of disaster.

In Somerset, the appearance of a rabbit in a village street was said to presage a coming fire, while in Dorset, a rabbit crossing one’s path in the morning was an indication of trouble ahead.

A remedy from 1875 suggests, "You can easily set matters right by spitting over your left shoulder, and saying, ‘Hare before, Trouble behind: Change ye, Cross, and free me,’ or else by the still more simple charm which consists in touching each shoulder with your forefinger, and saying, ‘Hare, hare, God send thee care.’"

Some Cornish fisherman would not let hares or rabbits on their boats, or say the names of these animals aloud, or use a net contaminated by contact with one of them. Hares were also associated with madness due to the wild abandon of their mating rituals.

The expression "Mad as a March hare" comes from the leaping and boxing of hares during their mating season.

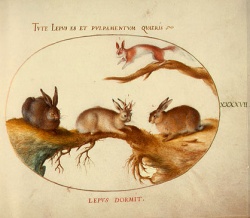

Despite this suspicious view of rabbits and their association with fertility and sexuality, Renaissance painters used the symbol of a white rabbit to convey a different meaning altogether: one of chastity and purity.

It was generally believed that female rabbits could conceive and give birth without contact with the male of the species, and thus virginal white rabbits appear in biblical pictures of the Madonna and Child.

The gentle timidity of rabbits also represented unquestioning faith in Christ’s Holy Church in paintings such as Titian’s Madonna with Rabbit (1530).

Rabbits and hares are both good and bad in trickster tales found all the way from Asia and Africa to North America.

In the Panchatantra tales of India, for example, Hare is a wily trickster whose cleverness and cunning is pitted against Elephant and Lion, while in Tibetan folktales, quick-thinking Hare outwits the ruses of predatory Tiger.

In Japan, the fox is the primary trickster animal, but hares too are clever, tricky characters.

Usually depicted as male (whereas fox tricksters are most often female), hares in Japanese folktales tend to be crafty, clownish, mischievous figures — as opposed to fox tricksters (kitsune), who are more seductive, secretive, and dangerous.

In West Africa, many tribal cultures, such as the Yoruba of Nigeria and the Wolof of Senegal, have traditional story cycles about an irrepressible hare trickster who is equal parts rascal, clown, and culture hero.

In one pan–African story, the Moon sends Hare, her divine messenger, down to earth to give mankind the gift of immortality.

"Tell them," she says, "that just as the Moon dies and rises again, so shall you."

But Hare, in the role of trickster buffoon, manages to get the message wrong, bestowing mortality instead and bringing death to the human world.

The Moon is so angry, she beats Hare with a stick, splitting his nose (as it remains today). It is Hare’s role to lead the dead to the Afterlife in penance for what he’s done.

African hare stories traveled to North America on the slavers’ ships, mixed with rabbit tales of the Cherokee and other tribes, and were transformed into the famous Br’er Rabbit stories of the American South.

These stories were passed orally among slaves, for whom Br’er (Brother) Rabbit was a perfect hero, besting more powerful opponents through his superior intelligence and quicker wits.

the The Br’er Rabbit stories were written down and published by Joel Chandler Harris in the 19th century in a now classic collection narrarated by the fictional Uncle Remus.

At the same time that Chandler Harris was recording Br’er Rabbit stories from the African American oral tradition, folklorist Alcee Fortier was setting down the folk tales of the Cajun (French Creole) culture of southern Louisiana — including delightful stories of a fast–talking rabbit trickster called Compair Lapin.

Like Br’er Rabbit, or the hares of West African lore, Compare Lapin is a rascal who manages to get himself into all kinds of trouble — and then smoothly finds his way back out again through cleverness and guile.

Among the many different Native American story traditions, trickster tales featuring Coyote or Raven tend to be best known to non–Native audiences, but there are also a large number of tales that feature a trickster Rabbit or Hare, particularly among the Algonquin–speaking peoples of the central and eastern woodland tribes.

Nanabozho (or Manabozho) the Great Hare, for instance, is a powerful figure found in the tales of the Algonquin, Fox, Menoimini, Ottawa, Ojibwa, and Winnebago tribes.

In some stories, Nanabozho is a revered culture hero — creator of the earth, benefactor of humankind, the bringer of light and fire, and teacher of sacred rituals. In other tales he’s a clown, a thief, a lecher, or a cunning predator — an ambivalent, amoral figure dancing on the line between right and wrong.

In Potawatomi myth, Wabosso is the Great White Hare (and the younger brother of Nanabozho) who travels north to become the greatest of magicians among the supernaturals.

The Utes tell the story of Ta–vwots, the Little Rabbit, who shatters the sun and destroys the world, all of which must be created again; and an Omaha rabbit brings the sun down to earth while trying to catch his own shadow.

The Cherokee, the Creek, the Biloxi and other tribes tell humorous stories of a mischievous Rabbit who is cousin to Br’er Rabbit and Compair Lapin, outwitting foes and puncturing the pride of friends with his clownish antics.

The jackalope legends of the American Southwest are stories of a more recent vintage, consisting of purported sightings of rabbits or hares with horns like antelopes.

The legend may have been brought to North American by German immigrants, derived from the Raurackl (or horned rabbit) of the German folklore tradition.

The jackalope legend might also derive from actual horn-like growths found on the heads and faces of rabbits infected with Shope papillomavirus, a rare, disfiguring disease found among the wild rabbit population.

Moving from myth and folklore to literature, rabbits and hares have appeared in several classic works of children’s fiction—most notably in The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1901) by the British author and illustrator Beatrix Potter.

Potter had been raised virtually imprisoned in a drearily proper London household by strict Victorian parents.

She found solace and escape during summer vacations spent in England’s Lake District.

The country life she loved there is beautifully evoked in her animal stories. Despite little formal art training (she was allowed to take only twelve painting lessons at the age of seventeen), Potter taught herself to draw and paint by painstakingly observing and copying nature.

Her charming stories of rabbit and mice, with their delicate, distinctive watercolor illustrations, were originally created as letters sent to children of her acquaintance.

These little stories proved so popular that she attempted to find a commercial outlet for them, but settled on publishing The Tale of Peter Rabbit herself after six companies turned her down.

The print run sold out instantly, and caught the attention of editor Norman Warne at Frederick Warne & Company. Not only did he take on the publication of Potter’s books, but he fell in love with the author too — and Peter Rabbit went on to become one of the best loved animal stories of all time.

Other creatures in the Literary Rabbit Hall of Fame include Lewis Carroll’s natty, time-obsessed White Rabbit in Alice in Wonderland, as well as his wild-eyed March Hare, spouting nonsense at the Mad Hatter’s tea party.

Adrienne Ségur, best known in America for her exquisite illustrations for The Golden Fairy Tale Book, started her illustration career in France in the 1930s with the publication of three rabbit tales: Aventures de Cotonnet; Cotonnet, aviateur; and Cotonnet en Amérique.

The Country Bunny and the Golden Shoes, written by Du Bose Heyward and illustrated by Marjorie Hack, is a remarkable 1939 feminist treatment of the Easter Bunny. The little country bunny stands up to the bigger jack rabbits to become a special Easter Rabbit.

The affable Rabbit in Winnie the Pooh by A.A. Milne is another character much loved by children, as is the stuffed toy bunny who comes magically to life in Margery Williams’ The Velveteen Rabbit and, more recently, the devilish vampire rabbit in Bunnicula by Deborah and James Howe.

Lynn Reid Banks' The Magic Hare is a sparkling collection contains ten folktales about magical hares, expertly retold by Banks and illustrated by American book artist Barry Moser.

In magical fiction for adult readers, Watership Down by Richard Adams is, of course, the great rabbit saga of our age, and comes complete with the mythological underpinnings of an elaborate rabbit mythology.

Less well known, but also delightful, is Garry Kilworth’s Frost Dancers, a beguiling novel set among the hares inhabiting the Scottish highlands.

A rabbit girl from the Sonoran desert of Arizona appears, rather shyly, in my own contemporary fantasy novel The Wood Wife; and one of her cousins subsequently turned up in the Arizona portion of Charles de Lint’s fine novel Forests of the Heart.

Medicine Road, also by Charles de Lint, features a woman who was once a jackalope among its cast of characters, deperately trying to hang on to her human skin, human life, and human lover. Graham Joyce's Limits of Enchantment is a gorgeous tale of midwifery, magic and the enchanted world of English hedgerows.

It's heroine is Fern Cullen, a crackling, smart girl, tricksterish like the hares who call her. Midori Snyder’s enchanting novel Hannah’s Garden contains one of the most compelling rabbit trickster figures in recent years, woven into a contemporary story about art, nature, Irish fiddle music, and the complexity of family bonds.

In films and cartoons, Bugs Bunny is the best known rabbit trickster of our age — equal parts rascal and culture hero, he’s an absolutely classic trickster type. Before Bugs, however, came Oswald the Lucky Rabbit, the first successful cartoon character created by the Walt Disney Studios.

Pre–dating Micky Mouse, Oswald’s popularity peaked and plummeted in the 1930s.

Thumper, the rabbit from the Disney film Bambi (1942), was another enormously popular figure — and became, oddly, an image used for World War II posters and insignia; one picture shows Thumper gleefully riding bronco–style on the back of a bomb.

In Harvey, the classic film of the 1950s, Jimmy Stewart played a man whose boon companion was a six–foot–three inch invisible rabbit; it’s a wonderful story that makes clever use of traditional Irish phooka legends.

More recently, rabbits have appeared in the exuberantly animated film Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, in the bizarre horror flick The Night of the Lepus, and as a chilling presence in the stylish and surreal cult film Donnie Darko.

Whether hovering above us in the arms of a moon goddess or carrying messages from the Netherworld below, whether clever or clownish, hero or rascal, whether portent of good tidings or ill, rabbits and hares have leapt through myths, legends, and folk tales all around the world – forever elusive, refusing to be caught and bound by a single definition.

The precise meaning, then, of the ancient Three Hares symbol carved into my village church is bound to be just as elusive and mutable as the myths behind it. It is a goddess symbol, a trickster symbol, a symbol of the Holy Trinity, a symbol of death, redemption and rebirth…all these and so much more.

Now, as I walk through Devon lanes in the long twilight of a summer’s evening, rabbits dart out of the hedgerows, stare at me with unblinking eyes, and disappear again over the crest of the shadowed hills. I’m reminded of a 19th century children’s poem by Walter de la Mare:

In the black furror of a field

I saw an old witch-hare this night;

And she cocked a lissome ear,

And she eyed the moon so bright,

And she nibbled of the green;

And I whispered "Whsst! witch-hare,"

Away like a ghostie o’er the field

She fled, and left the moonlight there.