The Tibetan Book and the Art of Blockprinting

Tibetan writing reads from left to right in horizontal lines. It does not employ ideograms like the Chinese, but uses an alphabet derived from a variant of the Devanagri script in which Sanskrit is written, consisting of thirty consonants and four vowels. The script, which is certainly one of the most exquisite forms of writing in Asia, is believed to have been created by Tönmi Sambhota (Thon mi Sambhota) in the mid-seventh century A.D. According to Tibetan tradition, Tönmi Sambhota was a minister of King Songtsen Gampo (Srong brtsan sgam po, c. 609-650 A.D.), the first Tibetan ruler to be converted to Buddhism. This King had two wives, Wen-ch'eng, the daughter of the Chinese Emperor T'ai-tsung, and Bhrikuti, a princess from Nepal. Both women were devout followers of Buddhism, and at their insistence Songtsen Gampo agreed to invite a number of Buddhist teachers from different parts of Asia. At the same time, he sent his minister Tönmi to India with instructions to enroll in one of the famed Buddhist universities so that he might learn the scribal arts and devise an alphabet suitable for the Tibetan language. After a long and harrowing journey, Tönmi finally arrived in India and for more than a decade sat at the feet of several Indian Buddhist masters, two of whom gave him the name Sambhota, "Good Tibetan." While studying in India, Tönmi Sambhota designed the letters of the Tibetan alphabet and compiled the first grammars of the Tibetan language, thereby providing the Tibetan people with a means for translating Indian Buddhist scriptures and for recording their own oral traditions. Here it should be stressed that even after the introduction of writing, these oral traditions continued to be a significant element in the transmission of Tibetan culture, in part due to the Buddhist assumption that authentic religious truths are most profoundly conveyed not through writing, but in direct communications between master and disciple.

The Tibetan script is considered sacred, since it was created especially for the translation of Buddhist scripture. Over the centuries several forms of lettering have developed, but the two principal types are the block letters, known as u-chen (dbu can, "headed letters"), and the cursive, called u-mé (dbu med, "headless letters"). The block letters are commonly employed in books and printed documents, while the cursive is used in more popular or personal formats. It is not unusual, however, to find printed material in Tibetan cursive. For titles and ornamental purposes other scripts are also employed, such as the high elegance of the seventeenth century Lantsa lettering.

The Tibetans designed their alphabet on Indian models, but the art of papermaking they borrowed from the Chinese. Tibetan paper is manufactured directly from root and vegetable fibers, which are in turn derived primarily from willow bark. In brief, the bark is soaked, beaten for several days, pulverized, and then spread out on a piece of cloth stretched across a wooden frame. After being dried in the sun for a few days, the mixture is ready to be cut as paper. Tibetan paper is strong and generally poisonous, for it is often treated with an arsenic-like substance to prevent it from being damaged by mold, fungi, or insects. People who spend a great deal of time around Tibetan books frequently complain of severe headaches, due in part to the heavy chemical odor.

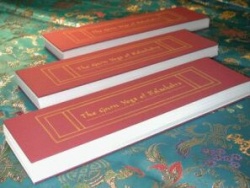

In Tibet, the most popular form of printing is woodblock. The art of woodblock printing arose in China at least as early as the ninth century, when it was employed for reproducing sacred texts and images. Standard Tibetan blockprinted books consist of separate, and often rather long, sheets of paper printed on both sides. Each sheet bears the abbreviated title of the work, the chapter and volume (if relevant), and the page number in the margin. The sheets are placed one on top of the other, wrapped in a cloth and then tied tightly between two covers (glegs shing) made from either wood or heavy cardstock. In the case of a special work, or one in several volumes, a strip of material with a protective flap of decorative brocade, indicating the volume and title, is generally slipped between the cloth wrapping so that it hangs loosely from the narrow edge of the text. With this unique method of identification, the book is made ready for accessible cataloguing and easy storage on library shelves. For reading, the text is placed across the knees or on a low table and each sheet is lifted, read from front to back, and then stacked facing page down in reverse order. Each page of a Tibetan book has to be printed using a separate woodblock. Soft woods, usually of hazel, birch, or walnut, are cut roughly to the shape of the book page, and the surface made smooth. A sheet of transparent paper bearing the letters of the desired text is placed face downward on the prepared block. The thin paper is then rubbed with a wet brush until a clear impression of the inverted letters is made on the smooth surface. The area of the block around the characters is subsequently cut away with a sharp knife, leaving the letters standing out in high relief. The printers work in groups of two. One selects the paper, while the other smears the woodblock with ink. The first lays the paper on the block and the second smooths it over with a brush. The printed page is then removed and left to dry. A clear and legible final print depends entirely upon the skill of the original woodcarving, the age and wear of the block, and the quality of paper used. Indeed, it is quite common to see a page from a Tibetan text that is barely decipherable due to smudges of bleeding ink or omissions of words or even parts of entire sentences.

Tibetans handle books with great reverence. Even if a text does not contain holy scripture, it is still approached as the verbal body of the Buddha, the provisional foundation of eternal truth or sung-den (gsung rten, "support of the exalted Word"). This explains why in Tibet books are never to be placed on the floor, at the level of one's feet, or in a low-lying impure space. Tibetan books are respected as powerful protections against evil and as paths to spiritual liberation. The tens of thousands of books that make up the vast corpus of Tibetan literature contain within their pages the abiding wisdom of over thirteen hundred years of spiritual pursuits. Tibet possesses one of the largest and most enduring literary traditions in all of Asia. Its influence has spread not only throughout the broader cultural regions that had once been dominated by the ancient Tibetan dynasty, including Mongolia, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, parts of northern Pakistan and Afghanistan, northern India, western China, and southern Russia, but also to Europe and Great Britain, Australia, Argentina, Canada, the United States, and Japan.

Source

[[Category:Tibetan Buddhist canon]