A History of Chinese Buddhism

This is a comprehensive account of the history of Chinese Buddhism from the earliest times to the 15th Century. While the author has based his work on extensive study, he does not seem to have full grasp of the history of orient as is evident from some of his conclusions about Indian art and mathematics. Like many historians of the British era, he believes that if there was something good about India or China it must have come from either Greece or Rome. Regarding Indian art the author believes that Indians had no art till the Greeks came to India and that Indians got their mathematics from Babylon. Ancient Indians had knowledge of art as early as 2500 BC as is evident from the excavations at many of sites of the Indus valley civilization and Indians had knowledge of mathematics and astronomy independent of Babylonians as is evident from many ancient Indian scriptures. - Jayaram

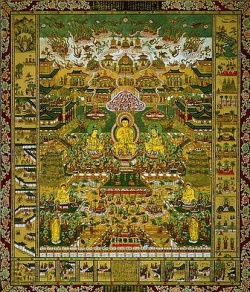

The emperor Ming-ti sends an embassy to India for images, A.D. 61—Kashiapmadanga arrives in China—Spread of Buddhism in A.D. 335—Buddojanga—A pagoda at Nanking, A.D. 381—The translator Kumarajiva, A.D. 405—The Chinese traveller, Fa-hien visits India—His book—Persecution, A.D. 426—Buddhism prosperous, 451—Indian embassies to China in the Sung dynasty—Opposition of the Confucianists to Buddhism—Discussions on doctrine—Buddhist prosperity in the Northern Wei kingdom and the Liang kingdom—Bodhidharma—Sung-yün sent to India—Bodhidharma leaves Liang Wu-ti and goes to Northern China—His latter years and death—Embassies from Buddhist countries m the south—Relics—The Liang emperor Wu-ti becomes a monk—Embassies from India and Ceylon—Influence of Sanscrit writing in giving the Chinese the knowledge of an alphabet—Syllabic spelling—Confucian opposition to Buddhism in the T‘ang dynasty—The five successors of Bodhidharma—Hiuen-tsang's travels in India—Work as a translator—Persecution, A.D. 714—Hindoo calendar in China—Amogha introduces the festival for hungry ghosts—Opposition of Han Yü to Buddhism—Persecution of 845—Teaching of Matsu—Triumph of the Mahayana—Budhiruchi—Persecution by the Cheu dynasty—Extensive erection of pagodas in the Sung dynasty—Encouragement of Sanscrit studies—Places of pilgrimage—P‘uto—Regulations for receiving the vows—Hindoo Buddhists in China in the Sung dynasty—The Mongol dynasty favoured Buddhism—The last Chinese Buddhist who visited India—The Ming dynasty limits the right of accumulating land—Roman Catholic controversy with Buddhists—Kang-hi of the Manchu dynasty opposes Buddhism—The literati still condemn Buddhism.

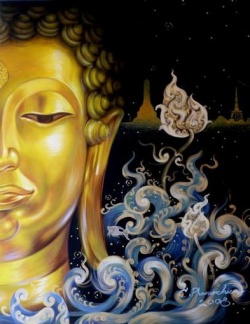

IT was in the year A.D. 61, that the Chinese emperor Ming-ti, in consequence of a dream, in which he saw the image of a foreign god, sent messengers to India, a country several thousand miles to the south-east of the capital, to ask for Buddhist books and teachers. 1 A native of Central India named Kashiapmadanga, with others, accompanied them back. He translated a small but important Sutra, called the Sutra of Forty-two Sections, and died at Lo-yang. The religion had now long been established in Nepaul and Independent Tartary, as the travels of the patriarchs indicate. It had also extended itself throughout India and Ceylon, and the persecution of the Brahmans, instigated partly by controversial feeling, and more by a desire to increase their caste influence, had not yet commenced. Long before this, it is stated that in B.C. 217, Indians had arrived at the capital of China in Shen-si, in order to propagate their religion. Remusat, after mentioning this in the Foĕ kouĕ ki, adds that, towards the year B.C. 122, a warlike expedition of the Chinese led them to Hieou-thou, a country beyond Yarkand. Here a golden statue was taken, and brought to the emperor. The Chinese author states that this was the origin of the statues of Buddha that were afterwards in use.

At this period the geographical knowledge of the Chinese rapidly increased. The name of India now occurs for the first time in their annals. In the year B.C. 122 Chang K‘ien, a Chinese ambassador, returned from the country of the Getæ, and informed the Han emperor Wu-ti, of the kingdoms and customs existing in the west. Among other things, he said, "When I was in the country of the Dahæ, 2 12,000 Chinese miles distant to the south-west, I saw bamboo staves from K’iung and cloth from Sï-ch’uen. On asking whence they came, I was told that they were articles of traffic at Shin-do ('Scinde,' a country far to the south-east of the Dahæ)." It is added in the commentary to the T’ung-kien-kang-muh, that the name is also pronounced, Kan-do and T’in-do, and that it is the country of the barbarians called Buddha.

Early in the fourth century, native Chinese began to take the Buddhist monastic vows. Their history says, under the year 335, that the prince of the Ch’au kingdom in the time of the Eastern Ts’in dynasty, permitted his subjects to do so. He was influenced by an Indian named Buddojanga, 1 who pretended to magical powers. Before this, natives of India had been allowed to build temples in the large cities, but it was now for the first time that the people of the country were suffered to become "Shamen" 2 (Shramanas), or disciples of Buddha. The first translations of the Buddhist books had been already made, for we read that at the close of the second century, an Indian residing at Ch’ang-an, the modern Si-an fu, produced the first version of the "Lotus of the Good Law." The emperor Hiau Wu, of the Ts’in dynasty, in the year A.D. 381, erected a pagoda in his palace at Nanking.

At this period, large monasteries began to be established in North China, and nine-tenths of the common people, says the historian, followed the faith of the great Indian sage.

Under the year A.D. 405, the Chinese chronicles record that the king of the Ts’in country gave a high office to Kumarajiva, an Indian Buddhist. This is an important epoch for the history of Chinese Buddhist literature. Kumarajiva was commanded by the emperor to translate the sacred books of India, and to the present day his name may be seen on the first page of the principal Buddhist classics. The seat of the ancient kingdom of Ts’in was in the southern part of the provinces Shen-si and Kan-su. Ch’au, another kingdom where, a few years previously, Buddhism was in favour at court, was in the modern Pe-chi-li and Shan-si. That this religion was then flourishing in the most northerly provinces of the empire, and that the date, place (Ch’ang-an), and other circumstances of the translations are preserved, are facts that should be remembered in connection with the history of the Chinese language. The numerous proper names and other words transferred from Sanscrit, and written with the Chinese characters, are of great assistance in ascertaining what sounds were then given to those characters in the region where Mandarin is now spoken.

Kumarajiva was brought to China from Kui-tsi, a kingdom in Tibet, east of the Ts’ung-ling mountains. The king of Ts’in had sent an army to invade that country, with directions not to return without the Indian whose fame had spread among all the neighbouring nations. The former translations of the Buddhist sacred books were to a great extent erroneous. To produce them in a form more accurate and complete was the task undertaken by the learned Buddhist just mentioned, at the desire of the king. More than eight hundred priests were called to assist, and the king himself, an ardent disciple of the new faith, was present at the conference, holding the old copies in his hand as the work of correction proceeded. More than three hundred volumes were thus prepared. 1

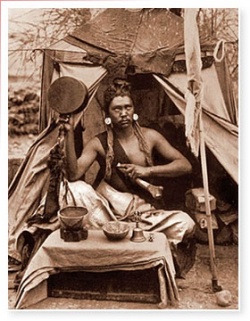

While this work, so favourable to the progress of Buddhism, was proceeding, a Chinese traveller, Fa-hien, was exploring India and collecting books. The extension of the religion that was then propagated with such zeal and fervour very much promoted the mutual intercourse of Asiatic countries. The road between Eastern Persia and China was frequently traversed, and a succession of Chinese Buddhists thus found their way to the parent land of the legends and superstitions in which they believed. Several of them on their return wrote narratives of what they had seen. Among those that have been preserved, the oldest of them, the Account of Buddhist Kingdoms, 1 by Fa-hien, is perhaps the most interesting and valuable. He describes the flourishing condition of Buddhism in the steppes of Tartary, among the Ouighours and the tribes residing west of the Caspian Sea, in Afghanistan where the language and customs of Central India then prevailed, and the other lands watered by the Indus and its tributary rivers, in Central India and in Ceylon. Going back by sea from Ceylon, he reached Ch‘ang-an in the year 414, after fifteen years’ absence. He then undertook with the help of Palats’anga, a native of India, the task of editing the works he had brought with him, and it was not till several years had elapsed that at the request of Kumarajiva, his religious instructor, he published his travels. The earnestness and vigour of the Chinese Buddhists at that early period, is shown sufficiently by the repeated journeys that they made along the tedious and dangerous route by Central Asia to India. Neither religion nor the love of seeing foreign lands, are now enough, unless the emperor commands it, to induce any of the educated class among them to leave their homes. Fa-hien had several companions, but death and other causes gradually deprived him of them all.

The Ts’in dynasty now fell (A.D. 420), and with it in quick succession the petty kingdoms into which China was at that time divided. The northern provinces became the possession of a powerful Tartar family, known in history as the Wei dynasty. A native dynasty, the first of the name Sung, ruled in the southern provinces. The princes of these kingdoms were at first hostile to Buddhism. Image making and the building of temples were forbidden, and in the north professors of the prohibited religion were subjected to severe persecution. The people were warned against giving them shelter, and in the year 426 an edict was issued against them, in accordance with which the books and images of Buddha were destroyed, and many priests put to death. To worship foreign divinities, or construct images of earth or brass, was made a capital crime. The eldest son of the Tartar chief of the Wei kingdom made many attempts to induce his father to deal less harshly towards a religion to which he himself was strongly attached, but in vain.

The work of this king was undone by his successor who, in the year A.D. 451, issued an edict permitting a Buddhist temple to be erected in each city, and forty or fifty of the inhabitants to become priests. The emperor himself performed the tonsure for some who took the monastic vows.

The rapid advancement of Buddhism in China was not unnoticed in neighbouring kingdoms. The same prosperity that awoke the jealousy of the civil government in the country itself, occasioned sympathy elsewhere. Many embassies came from the countries lying between India and China during the time of Sung Wen-ti. whose reign of more than thirty years closed in 453. Their chief object was to congratulate the ruling emperor on the prosperity of Buddhism in his dominions, and to pave the way for frequent intercourse on the ground of identity in religion. Two letters of Pishabarma, king of Aratan, to this emperor are preserved in the history of this dynasty. He describes his kingdom as lying in the shadow of the Himalayas, whose snows fed the streams that watered it. He praises China 1 as the most prosperous of kingdoms, and its rulers as the benefactors and civilisers of the world. The letter of the king of Jebabada, another Indian monarch, expresses his admiration of the same emperor in glowing language. He had given rest to the inhabitants of heaven and earth, subjected the four demons, attained the state of perfect perception, caused the wheel of the honoured law to revolve, saved multitudes of living beings, and by the renovating power of the Buddhist religion brought them into the happiness of the Nirvâna. Relics of Buddha were widely spread—numberless pagodas erected. All the treasures of the religion (Buddha, the Law, and the Priesthood) were as beautiful in appearance, and firm in their foundations as the Sumeru mountain. The diffusion of the sacred books and the law of Buddha was like the bright shining of the sun, and the assembly of priests, pure in their lives, was like the marshalled constellations of heaven. The royal palaces and walls were like those of the Tauli heaven. In the whole Jambu continent, there were no kingdoms from which embassies did not come with tribute to the great Sung emperor of the Yang-cheu 1 kingdom. He adds, that though separated by a wide sea, it was his wish to have embassies passing and repassing between the two countries.

The extensive intercourse that then began to exist between China and India may be gathered from the fact that Ceylon 1 also sent an embassy and a letter to Sung Wen-ti. In this letter it is said, that though the countries are distant three years’ journey by sea and land, there are constant communications between them. The king also mentions the attachment of his ancestors to the worship of Buddha.

The next of these curious memorials from Buddhist kings preserved in the annals of the same Chinese emperor, is that from "Kapili" (Kapilavastu), the birthplace of Shakyamuni, situated to the north-west of Benares.

The compiler of the Sung annals, after inserting this document, alludes to the flourishing state of Buddhism in the countries from which these embassies came, and in China itself. He then introduces a memorial from a magistrate representing the disorders that had sprung from the wide-spread influence of this religion, and recommending imperial interference. That document says that "Buddhism had during four dynasties been multiplying its images and sacred edifices. Pagodas and temples were upwards of a thousand in number. On entering them the visitor's heart was affected, and when he departed he felt desirous to invite others to the practices of piety. Lately, however, these sentiments of reverence had given place to frivolity. Instead of aiming at sincerity and purity of life, gaudy finery and mutual jealousies prevailed. While many new temples were erected for the sake of display, in the most splendid manner, no one thought of rebuilding the old ones. Official inquiries should be instituted to prevent further evils, and whoever wished to cast brazen statues should first obtain permission from the authorities."

A few years afterwards (A.D. 458) a conspiracy was detected in which a chief party was a Buddhist priest. An edict issued on the occasion by the emperor says, that among the priests many were men who had fled from justice and took the monastic vows for safety. They took advantage of their assumed character to contrive new modes of doing mischief. The fresh troubles thus constantly occurring excite the indignation of gods and men. The constituted authorities, it is added, must examine narrowly into the conduct of the monks. Those who are guilty must be put to death. It was afterwards enacted that such monks as would not keep their vows of abstinence and self-denial should return to their families and previous occupations. Nuns were also forbidden to enter the palace and converse with the emperor's wives.

The advances of Buddhism later in the fifth century were too rapid not to excite much opposition from the literati of the time, and a religious controversy was the result.

In the biography of Tsï Liang, a minister of state under the emperor Ts’i Wu-ti (A.D. 483), there are some fragments of a discussion he maintained in favour of Buddhism. He says, "If you do not believe in 'retribution of moral actions' (yin-kwo), then how can you account for the difference in the condition of the rich and the poor?" His opponent says, "Men are like flowers on trees, growing together and bent and scattered by the same breeze. Some fall upon curtains and carpets, like those whose lot is cast in palaces, while others drop among heaps of filth, representing men who are born in humble life. Riches and poverty, then, can be accounted for without the doctrine of retribution." To this the advocate of Buddhism is said to have been unable to reply. He also wrote on the destruction of the soul. Personating the Confucianists, he says that, "The 'soul' (shin) is to the 'body' (hing) as sharpness to the knife. The soul cannot continue to exist after the destruction of the body, more than sharpness can remain when the knife is no more." These extracts show that some of the Confucianists of that age denied any providential retribution in the present or a future life. Whatever may be thought of notions connected with ancestral worship, and the passages in the classical books that seem to indicate the knowledge of a separate life for the soul after death, they were too imperfect and indistinct to restrain the literati from the most direct antagonism on this subject with the early Buddhists. Holding such cheerless views as they did of the destiny of man, it is not to be wondered at that the common people should desert their standard, and adopt a more congenial system. The language of daily life is now thoroughly impregnated with the phraseology of retribution and a separate state. All classes make use of very many expressions in common intercourse which have been originated by Buddhism, thus attesting the extent of its influence on the nation at large. And, as the Buddhist immortality embraces the past as well as the future, the popular notions and language of China extend to a preceding life as much as to a coming one.

A distinct conception of the controversy as it then existed may be obtained from the following extracts from an account of a native Buddhist, contained in the biographical section of the History of the Sung dynasty:—"The instructions of Confucius include only a single life; they do not reach to a future state of existence, with its interminable results. His disciple, in multiplying virtuous actions, only brings happiness to his posterity. Vices do but entail greater present sufferings as their punishment. The rewards of the good do not, according to this system, go beyond worldly honour, nor does the recompense of guilt include anything worse than obscurity and poverty. Beyond the ken of the senses nothing is known; such ignorance is melancholy. The aims of the doctrine of Shakya, on the other hand, are illimitable. It saves from the greatest dangers, and removes every care from the heart. Heaven and earth are not sufficient to bound its knowledge. Having as its one sentiment, mercy seeking to save, the renovation of all living beings cannot satisfy it. It speaks of hell, and the people fear to sin; of heaven, and they all desire its happiness. It points to the Nirvâna as the spirit's 'final home' (ch’ang-kwei, lit. 'long return'), and tells him of 'the bodily form of the law' (fa-shen), 1 as that last, best spectacle, on which the eye can gaze. There is no region to which its influence does not reach. It soars in thought into the upper world. Beginning from a space no larger than the well's mouth in a courtyard, it extends its knowledge to the whole adjacent mansion." These sentiments are replied to, in the imaginary dialogue in which they occur, by a Confucian, who says, "To be urged by the desire of heaven to the performance of virtue, cannot bear comparison with doing what is right for its own sake. To keep the body under restraint from the fear of hell, is not so good as to govern the heart from a feeling of duty. Acts of worship, performed for the sake of obtaining forgiveness of sins, do not spring from piety. A gift, made to secure a hundredfold recompense to the giver, cannot come from pure inward sincerity. To praise the happiness of the Nirvâna promotes a lazy inactivity. To speak highly of the beauty of the embodied ideal representation of Buddhist doctrine, seen by the advanced disciple, tends to produce in men a love of the marvellous. By your system, distant good is looked for, while the desires of the animal nature, which are close at hand, are unchecked. Though you say that the Bodhisattwa is freed from these desires, yet all beings, without exception, have them." To these arguments for the older Chinese system, the Buddhist comes forward with a rejoinder:—"Your conclusions are wrong. Motives derived from a future state are necessary to lead men to virtue. Otherwise how could the evil tendencies of the present life be adjusted? Men will not act spontaneously and immediately without something to hope for. The countryman is diligent in ploughing his land, because he expects a harvest. If he had no such hope, he would sit idle at home, and soon go down for ever 'below the nine fountains.'" 1 The Confucian answers that "religion" (tau) consisting in the repression of all desires, it is inconsistent to use the desire of heaven as a motive to virtue.

The discussion is continued with great spirit through several pages, turning entirely on the advantage to be derived from the doctrine of the future state for the inculcation of virtue. The Buddhist champion is called the teacher of the "black doctrine," and his opponent that of "the white." The author, a Buddhist, has given its full force to the Confucian reasoning, while he condemns without flinching the difficulties that he sees in the system he opposes. The whole is preserved in a beautifully finished style of composition, and is a specimen of the valuable materials contained in the Chinese dynastic histories for special inquiries on many subjects not concerned with the general history of the country. It was with fair words like these, the darker shades of Buddhism being kept out of view, that the contest was maintained in those days by such as would introduce a foreign form of worship, against the adherents to the maxims of Confucius. The author of the piece was rewarded for it by the reigning emperor.

In the northern provinces Buddhism was now flourishing. The prince of the Wei kingdom spared no expense in promoting it. History says, that in the year 467 he caused an image to be constructed "forty-three feet" in height (thirty-five English feet). A hundred peculs of brass, or more than five tons, were used, and six peculs of gold. Four years after, he resigned his throne to his son, and became a monk. When, about the same time, the Sung emperor erected a magnificent Buddhist temple, he was severely rebuked by some of his mandarins.

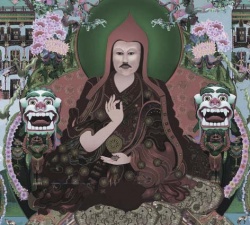

The time of Wu-ti, the first emperor of the Liang dynasty, forms an era in the history of Chinese Buddhism, marked as it was by the arrival in China of Ta-mo (Bodhidharma), the twenty-eighth of the patriarchs, and by the extraordinary prosperity of the Buddhist religion under the imperial favour.

At the beginning of the sixth century, the number of Indians in China was upwards of three thousand. The prince of the Wei kingdom exerted himself greatly to provide maintenance for them in monasteries, erected on the most beautiful sites. Many of them resided at Lo-yang, the modern Ho-nan fu. The temples had multiplied to thirteen thousand. The decline of Buddhism in its motherland drove many of the Hindoos to the north of the Himalayas. They came as refugees from the Brahmanical persecution, and their great number will assist materially in accounting for the growth of the religion they propagated in China. The prince of the Wei country is recorded to have discoursed publicly on the Buddhist classics. At the same time, he refused to treat for peace with the ambassadors of his southern neighbour, the Liang kingdom. Of this the Confucian historian takes advantage, charging him with inconsistency in being attached to a religion that forbids cruelty and bloodshed, while he showed such fondness for war.

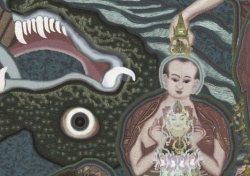

Soon after this, several priests were put to death (A.D. 515) for practising magical arts. This is an offence attributed more than once by the Chinese historians to the early Buddhists. The use of charms, and the claim to magical powers, do not appear to have belonged to the system as it was left by Shakyamuni. His teaching, as Burnouf has shown, was occupied simply with morals and his peculiar philosophy. After a few centuries, however, among the additions made by the Northern Buddhists to popularise the religion, and give greater power to the priests, were many narratives full of marvels and impossibilities, falsely attributed to primitive Buddhism. These works are called the Ta-ch’eng, or "Great Development" Sutras. Another novelty was the pretence of working enchantments by means of unintelligible formulæ, which are preserved in the books of the Chinese Buddhists, as in those of Nepaul, without attempt at explanation. These charms are called Dharani. They occur in the Great Development classics, such as the "Lotus of the Good Law," Miau-fa-lien-hwa-king (Fa-hwa-king), and in various Buddhist works. The account given in the T’ung-kien-kang-muh of the professed magician who led the priests referred to above, says that he styled himself Ta-ch’eng, used wild music to win followers, taught them to dissolve all the ties of kindred, and aimed only at murder and disturbance.

The native annotator says that Ta-ch’eng is the highest of three states of intelligence to which a disciple of Buddha can attain, and that the corresponding Sanscrit word, Mahayana, means "Boundless revolution and unsurpassed knowledge." It is here that the resemblance is most striking between the Buddhism of China and that of other countries where it is professed in the north. These countries having the same additions to the creed of Shakya, the division of Buddhism by Burnouf into a Northern and Southern school has been rightly made. The superadded mythology and claim to magical powers of the Buddhists, who revere the Sanscrit as their sacred language, distinguish them from their co-religionists who preserve their traditions in the Pali tongue.

In the year A.D. 518, Sung-yün was sent to India by the prince of the Wei country for Buddhist books. He was accompanied by Hwei-sheng, a priest. He travelled to Candahar, stayed two years in Udyana, and returned with 175 Buddhist works. His narrative has been translated by Professor Neumann into German.

In A.D. 526, Bodhidharma, after having grown old in Southern India, reached Canton by sea. The propagation of Buddhism in his native country he gave in charge to one of his disciples during his absence. He was received with the honour due to his age and character, and immediately invited to Nanking, where the emperor of Southern China, Liang Wu-ti, held his court. The emperor said to him—"From my accession to the throne, I have been incessantly building temples, transcribing sacred books, and admitting new monks to take the vows. How much merit may I be supposed to have accumulated?" The reply was, "None." The emperor: "And why no merit?" The patriarch: "All this is but the insignificant effect of an imperfect cause not complete in itself. It is the shadow that follows the substance, and is without real existence." The emperor: "Then what is true merit?" The patriarch: "It consists in purity and enlightenment, depth and completeness, and in being wrapped in thought while surrounded by vacancy and stillness. Merit such as this cannot be sought by worldly means." The emperor: "Which is the most important of the holy doctrines?" The patriarch: "Where all is emptiness, nothing can be called 'holy' (sheng)." The emperor: "Who is he that thus replies to me?" The patriarch: "I do not know." The emperor—says the Buddhist narrator—still remained unenlightened. This extract exhibits Buddhism very distinctly in its mystic phase. Mysticism can attach itself to the most abstract philosophical dogmas, just as well as to those of a properly religious kind. This state of mind, allying itself indifferently to error and to truth, is thus shown to be of purely subjective origin. The objective doctrines that call it into existence may be of the most opposite kind. It grows, therefore, out of the mind itself. Its appearance may be more naturally expected in the history of a religion like Christianity, which awakens the human emotions to their intensest exercise, while, in many ways, it favours the extended use of the contemplative faculties, and hence the numerous mystic sects of Church history. Its occurrence in Buddhism, and its kindred systems, might with more reason occasion surprise, founded as they are on philosophical meditations eminently abstract. It was reserved for the fantastic genius of India to construct a religion out of three such elements as atheism, annihilation, and the non-reality of the material world; and, by the encouragement of mysticism and the monastic life, to make these most ultimate of negations palatable and popular. The subsequent addition of a mythology suited to the taste of the common people was, it should be remembered, another powerful cause, contributing, in conjunction with these quietist and ascetic tendencies, to spread Buddhism through so great a mass of humankind. In carrying out his mystic views, Ta-mo discouraged the use of the sacred books. He represented the attainment of the Buddhist's aim as being entirely the work of the heart. Though he professed not to make use of books, his followers preserved his apophthegms in writing, and, by the wide diffusion of them, a numerous school of contemplatists was originated, under the name of Ch‘an-hio (dhyana doctrine) and Ch‘an-men (dhyana school).

Bodhidharma, not being satisfied with the result of his interview with royalty, crossed the Yang-tsze keang into the Wei kingdom and remained at Lo-yang. Here, the narrative says, he sat with his face to a wall for nine years. The people called him the "Wall-gazing Brahman." 1 When it was represented to the Liang emperor, that the great teacher, who possessed the precious heirloom of Shakya, the symbol of the hidden law of Buddha, was lost to his kingdom, he repented and sent messengers to invite him to return. They failed in their errand. The presence of the Indian sage excited the more ardent Chinese Buddhists to make great efforts to conquer the sensations. Thus one of them, we are told, said to himself, "Formerly, for the sake of religion, men broke open their bones and extracted the marrow, took blood from their arms to give to the hungry, rolled their hair in the mud, or threw themselves down a precipice to feed a famishing tiger. What can I do?" Accordingly, while snow was falling, he exposed himself to it till it had risen above his knees, when the patriarch observing him, asked him what he hoped to gain by it. The young aspirant to the victory over self wept at the question, and said, "I only desire that mercy may open a path to save the whole race of mankind." The patriarch replied, that such an act was not worthy of comparison with the acts of the Buddhas. It required, he told him, very little virtue or resolution. His disciple, stung with the answer, says the legend, took a sharp knife, severed his arm, and placed it before the patriarch. The latter expressed his high approval of the deed, and when, after nine years’ absence, he determined to return to India, he appointed the disciple who had performed it to succeed him as patriarch in China. He said to him on this occasion, "I give you the seal of the law as the sign of your adherence to the true doctrine inwardly, and the kasha (robe worn by Buddhists) as the symbol of your outward teaching. These symbols must be delivered down from one to another for two hundred years after my death, and then, the law of Buddha having spread through the whole nation, the succession of patriarchs will cease." He further said, "I also consign to you the Lenga Sutra in four sections, which opens the door to the heart of Buddha, and is fitted to enlighten all living men." Ta-mo's further instructions to his successor as to the nature and duties of the patriarchate are fully detailed in the Chï-yue-luh. He died of old age after five attempts to poison him, and was buried at the Hiung-er mountains between Ho-nan and Shen-si. At this juncture Sung-yün, who had been sent to India a few years previously for Buddhist books, returned, and inspected the remains of Bodhidharma. As he lay in his coffin he held one shoe in his hand. Sun;-yün asked him whither he was going. "To the Western heaven," was the reply. Sung-yün then returned home. The coffin was afterwards opened and found empty, excepting that one of the patriarch's shoes was lying there. By imperial command, the shoe was preserved as a sacred relic in the monastery. Afterwards in the T‘ang dynasty it was stolen, and now no one knows where it is.

The embassies from Buddhist kingdoms in the time of Liang Wu-ti afford other illustrations of the passion for relics and mementoes of venerated personages, encouraged by the Buddhist priests. The king of Bunam, the ancient Siam, wrote to the emperor that he had a hair of Buddha, twelve feet in length, to give him. Priests were sent from the Chinese court to meet it, and bring it home. Three years before this, as the History of the Liang dynasty informs us, in building, by imperial command, a monastery and pagoda to king A-yo (Ashôka), a sharira, or "relic of Buddha," had been found under the old pagoda, with a hair of a blue lavender colour. This hair was so elastic that when the priests pulled it, it lengthened ad libitum, and when let alone curled into a spiral form. The historian quotes two Buddhist works in illustration. The "Seng-ga Sutra" (king) says, that Buddha's hair was blue and fine. In the San-mei-king, Shakya himself says, "When I was formerly in my father's palace, I combed my hair, and measuring it, found that it was twelve feet in length. When let go, it curled into a spiral form." This description agrees, it is added, with that of the hair found by the emperor.

In A.D. 523, the king of Banban sent as his tributary offering, a true "sharira" (she-li) with pictures and miniature pagodas; also leaves of the Bodhi, Buddha's favourite tree. The king of another country in the Birmese peninsula had a dream, in which a priest appeared to him and foretold to him that the new prince of the Liang dynasty would soon raise Buddhism to the summit of prosperity, and that he would do wisely if he sent him an embassy. The king paying no attention to the warning, the priest appeared again in a second dream, and conducted the monarch to the court of Liang Wu-ti. On awaking, the king, who was himself an accomplished painter, drew the likeness of the emperor as he had seen him in his dream. He now sent ambassadors and an artist with instructions to paint a likeness of the Chinese monarch from life. On comparing it with his own picture, the similarity was found to be perfect.

This emperor, so zealous a promoter of Buddhism, in the year A.D. 527, the twenty-sixth of his reign, became a monk and entered the Tung-tai monastery in Nanking. The same record is made in the history two years afterwards. As might be expected, this event calls forth a long and severe critique from the Confucian historian. The preface to the history of the dynasty established by this prince, consists solely of a lament over the sad necessity of adverting to Buddhism in the imperial annals of the nation, with an argument for the old national system, which is so clearly right, that the wish to deviate from it shows a man to be wrong. In reference to the emperor's becoming a priest, the critic says, "that not only would the man of common intelligence condemn such conduct in the ruler of a commonwealth, but even men like Bodhidharma would withhold their approval."

A few years afterwards, the same emperor rebuilt the Ch’ang-ts’ien monastery five le to the south of "Nanking," in which was the tope (shrine for relics) of A-yo or Ashôka. The writer in the T‘ung-kien-kang-muh adds, that a true relic of Buddha's body is preserved near "Ming-cheu" (now Ningpo). Ashôka erected 80,000 topes, of which one-nineteenth were assigned to China. The tope and relic here alluded to are those of the hill Yo-wang shan, well known to foreign visitors, and situated fifty-two li eastward of Ningpo. To Buddhist pilgrims coming from far and near to this sacred spot, the she-li is an object of reverential worship, but to unbelieving eyes it presents a rather insignificant appearance. The small, reddish, beadlike substance that constitutes the relic, is so placed in its lantern-shaped receptacle, that it does not admit of much light being thrown upon it. The colour is said to vary with the state of mind of the visitor. Yellow is that of happiest omen. The theory is a safe one, for there is just obscurity enough to render the tint of the precious remains of Shakya's burnt body somewhat uncertain.

King Ashôka, to whom this temple is dedicated, was one of the most celebrated of the Buddhist kings of India. Burnouf in his Introduction à l’Histoire du Buddhisme Indien, has translated a long legend of which Ashôka is the hero, and which is also contained in the Chinese work, Fa-yuen-chu-lin. The commencement in the latter differs a little from that given by Burnouf. Buddha says to Ananda, "You should know that in the city 'Palinput' (Pataliputra), there will be a king named 'The moon protected' (Yue-hu; in Sanscrit, Chandragupta). He will have a son named Bindupala, and he again will have a son Susima." Ashôka was the son of Bindupala by another wife, and succeeded his father as king. The Indian king Sandracottus, who concluded a treaty with Seleucus Nicator, the Greek king of Syria, B.C. 305, was identified with Chandragupta by Schlegel and Wilson. According to the Mahavanso, the Pali history of the Buddhist patriarchs, there was an interval of 854 years from Buddha's death to the accession of Chandragupta, making that event to be in B.C. 389, which is more than half a century too soon. Turnour thinks the discrepancy cannot be accounted for but by supposing a wilful perversion of the chronology. These statements are quoted in Hardy's Eastern Monachism, from Wilson's Vishnu Purana. By this synchronism of Greek and Indian literature, it is satisfactorily shown that Ashôka lived in the second century before Christ, and Buddha in the fourth and fifth. The commonly received chronology of the Chinese Buddhists is too long, therefore, by more than five hundred years. 1 Probably this fraud was effected to verify predictions found in certain Sutras, in which Buddha is made to say that in a definite number of years after his death, such and such things would happen. The Northern Buddhists wrote in Sanscrit, made use of Sanscrit Sutras, and were anxious to vindicate the correctness of all predictions found in them. Burnouf supposes that the disciples of Buddha, would naturally publish their sacred books in more than one language; Sanscrit being then, and long afterwards, spoken by the literati, while derived dialects were used by the common people. By Fa-hien Ashôka is called A-yo Wang, as at the monastery near Ningpo. In Hiuen-tsang's narrative, the name Wu-yeu wang, the "Sorrowless king," a translation of the Sanscrit word, is applied to him.

The Liang emperor Wu-ti, after three times assuming the, Buddhist vows and expounding the Sutras to his assembled courtiers, was succeeded by a son who favoured Tauism. A few years after, the sovereign of the Ts’i kingdom endeavoured to combine these two religions. He put to death four Tauist priests for refusing to submit to the tonsure and become worshippers of Buddha. After this there was no more resistance. In A.D. 558 it is related that Wu-ti, an emperor of the Ch’in dynasty, became a monk. Some years afterwards, the prince of the Cheu kingdom issued an edict prohibiting both Buddhism and Tauism. Books and images were destroyed, and all professors of these religions compelled to abandon them.

The History of the Northern Wei dynasty contains some details on the early Sanscrit translations in addition to what has been already inserted in this narrative. 1 The pioneers in the work of translation were Kashiapmadanga and Chu-fa-lan, who worked conjointly in the time of Ming-ti. The latter also translated the "Sutra of the ten points of rest." In A.D. 150, a priest of the "An-si" (Arsaces) country in Eastern Persia is noticed as an excellent translator. About A.D. 170, Chitsin, a priest of the Getæ nation, produced a version of the Nirvâna Sutra. Sun K’iuen, prince of the Wu state, one of the Three Kingdoms, who, some time after the embassy of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, the Roman emperor, to China, received with great respect a Roman merchant at his court, 1 treated with equal regard an Indian priest who translated for him some of the books of Buddha. The next Indian mentioned is Dharmakakala, who translated the "Vinaya" or Kiai-lü (Discipline) at Lo-yang. About A.D. 300, Chï-kung-ming, a foreign priest, translated the Wei-ma and Fa-hwa, 2 "Lotus of the Good Law Sutras," but the work was imperfectly done. Tau-an, a Chinese Buddhist, finding the sacred books disfigured by errors, applied himself to correct them. He derived instruction from Buddojanga and wished much to converse with Kumarajiva, noticed in a previous page. The latter, himself a man of high intelligence, had conceived an extraordinary regard for him, and lamented much when he came to Ch’ang-an from Liang-cheu at the north-western corner of China where he had long resided, that Tau-an was dead. Kumarajiva found that in the corrections he proposed to make in the sacred books, he had been completely anticipated by his Chinese fellow-religionist. Kumarajiva is commended for his accurate knowledge of the Chinese language as well as of his own. With his assistants he made clear the sense of many profound and extensive "Sutras" (King) and "Shastras" (Lun), twelve works in all. The divisions into sections and sentences were formed with care. The finishing touch to the Chinese composition of these translations was given by Seng-chau. Fa-hien in his travels did his utmost to procure copies of the Discipline and the other sacred books. On his return, with the aid of an Indian named Bhadra, he translated the Seng-kï-lü (Asangkhyea Vinaya), which has since been regarded as a standard work.

Before Fa-hien's time, about A.D. 290, a Chinese named Chu Sï-hing went to Northern India for Buddhist books. He reached Udin or Khodin, identified by Remusat with Khoten, and obtained a Sutra of ninety sections. He translated it in Ho-nan, with the title Fang-kwang-pat-nia-king (Light-emitting Prajna Sutra). Many of these books at that time so coveted, were brought to Lo-yang, and translated there by Chufahu, a priest of the Getæ nation, who had travelled to India, and was a contemporary of the Chinese just mentioned. Fa-ling was another Chinese who proceeded from "Yang-cheu" (Kiang-nan) to Northern India and brought back the Sutra Hwa-yen-king and the Pen-ting-lü, a work on discipline. Versions of the "Nirvâna Sutra" (Ni-wan-king), and the Seng-ki-lü were made by Chi-meng in the country Kau-ch‘ang, or what is now "Eastern Thibet." The translator had obtained them at Hwa-shï or "Pataliputra," a city to the westward. The Indian Dharmaraksha brought to China a new Sanscrit copy of the Nirvâna Sutra and going to Kau-ch‘ang, compared it with Chi-meng's copy for critical purposes. The latter was afterwards brought to Ch‘ang-an and published in thirty chapters. The Indian here mentioned, professed to foretell political events by the use of charms. He also translated the Kin-kwang-king, or "Golden Light Sutra," and the Ming-king, "Bright Sutra." At this time there were several tens of foreign priests at Ch‘ang-an, but the most distinguished among them for ability was Kumarajiva. His translations of the Wei-ma, Fa-hwa, and C‘heng-shih (complete) Sutras, with the three just mentioned, by Dharmaraksha and some others, together form the Great Development course of instruction. The "Longer Agama Sutra" 1 and the "Discipline of the Four Divisions" 2 were translated by Buddhayasha, a native of India, the "Discipline of the Ten Chants" 3 by Kumarajiva, the "Additional Agama Sutra" by Dharmanandi, and the "Shastra of Metaphysics" (Abhidharma-lun) by Dharmayagama. These together formed the Smaller Development course. In some monasteries the former works were studied by the recluses; in others the latter. Thus a metaphysical theology, subdivided into schools, formed the subject of study in the Asiatic monkish establishments, as in the days of the European school-men. The Chinese travellers in India, and in the chain of Buddhist kingdoms extending—before the inroads of Mohammedanism—from their native land into Persia, give us the opportunity of knowing how widely there as well as in China the monastic life and the study of these books were spread. About A.D. 400, Sangadeva, a native of "Cophen" (Kipin), translated two of the Agama Sutras. The "Hwa-yen Sutra" was soon afterwards brought from Udin by Chi Fa-ling, a Chinese Buddhist, and a version of it made at Nanking. He also procured the Pen-ting-lü, a work in the Vinaya or "Discipline" branch of Buddhist books. Ma Twan-lin also mentions a Hindoo who, about A.D. 502, translated some Shastras of the Great Development (Ta-ch‘eng) school, called Ti-ch‘ï-lun (fixed position), and Shi-ti-lun (the ten positions).

The Hindoo Buddhists in China, whose literary labours down to the middle of the sixth century are here recorded, while they sometimes enjoyed the imperial favour, had to bear their part in the reverses to which their religion was exposed. Dharmaraksha was put to death for refusing to come to court on the requisition of one of the Wei emperors. Sihien, a priest of the royal family of the Kipin kingdom in Northern India, in times of persecution assumed the disguise of a physician, and when the very severe penal laws then enacted against Buddhism were remitted, returned to his former mode of life as a monk. Some other names might be added to the list of Hindoo translators, were it not already sufficiently long.

About the year 460 it appears from the history that five Buddhists from Ceylon arrived in China by the Thibetan route. Two of them were Yashaita and Budanandi. They brought images. Those constructed by the latter had the property of diminishing in apparent size as the visitor drew nearer, and looking brighter as he went farther away. Though a literary character is not attributed to them, the Southern Buddhist traditions might, through their means, have been communicated at this time to the Chinese. This may account for the date—nearly correct—assigned to the birth of Buddha in the History of the Wei dynasty, from which these facts are taken, and in that of the Sui dynasty which soon followed.

According to the same history there were then in China two millions of priests and thirty thousand temples. This account must be exaggerated; for if we allow a thousand to each district, which is probably over the mark, there will be but that number at the present time, although the population has increased very greatly in the interval. 1

Buddhism received no check from the Sui emperors, who ruled China for the short period of thirty-seven years. The first of them, on assuming the title of emperor in 581, issued an edict giving full toleration to this sect. Towards the close of his reign he prohibited the destruction or maltreatment of any of the images of the Buddhist or Tauist sects. It was the weakness of age, says the Confucian historian, giving way to superstitions that led him to such an act as this. The same commentator on the history of the period says, that the Buddhist books were at this time ten times more numerous than the Confucian classics. The Sui History in the digest it gives of all the books of the time, states those of the Buddhist sect to be 1950 distinct works. Many of the titles are given, and among them are not a few treating of the mode of writing by alphabetic symbols used in the kingdoms from whence Buddhism came. The first alphabet that was thus introduced appears to have been one of fourteen symbols. It is called Si-yo hu-shu or "Foreign Writing of the Western countries," and also Ba-la-men-shu, "Brahmanical writing." The tables of initials and finals found in the Chinese native dictionaries were first formed in the third century, but more fully early in the sixth century, in the Liang dynasty. It was then that the Hindoos, who had come to China, assisted in forming, according to the model of the Sanscrit alphabet, a system of thirty-six initial letters, and described the vocal organs by which they are formed. They also constructed tables, in which, by means of two sets of representative characters, one for the initials and another for the finals, a mode of spelling words was exhibited. The Chinese were now taught for the first time that monosyllabic sounds are divisible into parts, but alphabetic symbols were not adopted to write the separated elements. It was thought better to use characters already known to the people. A serious defect attended this method. The analysis was not carried far enough. Intelligent Chinese understand that a sound, such as man, can be divided into two parts, m and an; for they have been long accustomed to the system of phonetic bisection here alluded to, but they usually refuse to believe that a trisection of the sound is practicable. At the same time the system was much easier to learn than if foreign symbols had been employed, and it was very soon universally adopted. Shen-kung, a priest, is said to have been the author of the system, and the dictionary Yü-p’ien was one of the first extensive works in which it was employed. 1 That the Hindoo Buddhists should have taught the Chinese how to write the sounds of this language by an artifice which required nothing but their own hieroglyphics, and rendered unnecessary the introduction of new symbols, is sufficient evidence of their ingenuity, and is not the least of the services they have done to the sons of Han. It answered well for several centuries, and was made use of in all dictionaries and educational works. But the language changed, the old sounds were broken up, and now the words thus spelt are read correctly only by those natives who happen to speak the dialects that most nearly resemble in sound the old pronunciation.

To Shen Yo, the historian of two dynasties, and author of several detached historical pieces, is attributed the discovery of the four tones. His biographer says of him in the "Liang History:"—"He wrote his 'Treatise on the Four Tones,' to make known what men for thousands of years had not understood—the wonderful fact which he alone in the silence of his breast came to perceive." It may be well doubted if the credit of arriving unassisted at the knowledge of this fact is due to him. He resided at the court of Liang Wu-ti, the great patron of the Indian strangers. They, accustomed to the unrivalled accuracy in phonetic analysis of the Sanscrit alphabet, would readily distinguish a new phenomenon like this, while to a native speaker, who had never known articulate sounds to be without it, it would almost necessarily be undetected. In the syllabic spelling that they formed, the tones are duly represented, by being embraced in every instance in the final.

The extent of influence which this nomenclature for sounds has attained in the native literature is known to all who are familiar with its dictionaries, and the common editions of the classical books. In this way it is that the traditions of old sounds needed to explain the rhymes and metre of the ancient national poetry are preserved. By the same method the sounds of modern dialects that have deviated extensively from the old type have been committed to writing. The dialects of the Mandarin provinces, of Northern and Southern Fu-kien, and Canton have been written down by native authors each with its one system of tones and alphabetic elements, and they have all taken the method introduced by the Buddhists as their guide. The Chinese have since become acquainted with several alphabets with foreign symbols, but when they need to write phonetically they prefer the system, imperfect as it is, that does not oblige them to abandon the hieroglyphic signs transmitted by their ancestors. Never, perhaps, since the days of Cadmus, was a philological impulse more successful than that thus communicated from India to the Chinese, if the extent of its adoption be the criterion. They have not only by the use of the syllabic spelling thus taught them, collected the materials for philological research afforded by the modern dialects, but, by patient industry, have discovered the early history of the language, showing how the number of tones increased from two to three by the time of Confucius, to four in the sixth century of our era, and so on to their present state. Few foreign investigators have yet entered on this field of research, but it may be suggested that the philology of the Eastern languages must without it be necessarily incomplete, and that the Chinese, by patience and a true scientific instinct, have placed the materials in such a form that little labour is needed to gather from them the facts that they contain.

The Thibetans, and, probably, the Coreans also, owe their alphabets, which are both arranged in the Sanscrit mode, to the Buddhists. Corean ambassadors came in the reign of Liang Wu-ti to ask for the "Nirvâna" and other Buddhistic classics. It may then have been as early as this that they had an alphabet, but the writing now in use dates from about A.D. 1360, as Mr. Scott has shown. 1 The first emperor of the T‘ang dynasty was induced by the representations of Fu Yi, one of his ministers, to call a council for deliberation on the mode of action to be adopted in regard to Buddhism. Fu Yi, a stern enemy of the new religion, proposed that the monks and nuns should be compelled to marry and bring up families. The reason that they adopted the ascetic life, he said, was to avoid contributing to the revenue. What they held about the fate of mankind depending on the will of Buddha was false. Life and death were regulated by a "natural necessity" with which man had nothing to do (yeu-ü-tsï-jan). The retribution of vice and virtue was the province of the prince, while riches and poverty were the recompense provoked by our own actions. The public manners had degenerated lamentably through the influence of Buddhism. The "six states of being" 1 into which the souls of men might be born were entirely fictitious. The monks lived an idle life, and were unprofitable members of the commonwealth. To this it was replied in the council, by Siau Ü, a friend of the Buddhists, that Buddha was a "sage" (shing-jen), and that Fu Yi having spoken ill of a sage, was guilty of a great crime. To this Fu Yi answered, that the highest of the virtues were loyalty and filial piety, and the monks, casting off as they did their prince and their parents, disregarded them both. As for Siau Ü, he added, he was—being the advocate of such a system—as destitute as they of these virtues. Siau Ü joined his hands and merely replied to him, that hell was made for such men as he. The Confucianists gained the victory, and severe restrictions were imposed on the professors of the foreign faith, but they were taken off almost immediately after.

The successors of Bodhidharma were five in number. They are styled with him the six "Eastern patriarchs," Tung-tsu. They led quiet lives. The fourth of them was invited to court by the second emperor of the T‘ang dynasty, and repeatedly declined the honour. When a messenger came for the fourth time and informed him that, if he refused to go, he had orders to take his head back with him, the imperturbable old man merely held out his neck to the sword in token of his willingness to die. The emperor respected his firmness. Some years previously, with a large number of disciples, he had gone to a city in Shansi. The city was soon after laid siege to by rebels. The patriarch advised his followers to recite the "Great Prajna," Ma-ha-pat-nia, an extensive work, in which the most abstract dogmas of Buddhist philosophy are very fully developed. The enemy, looking towards the ramparts, thought they saw a band of spirit-soldiers in array against them, and consequently retired.

In the year 629 the celebrated Hiuen-tsang set out on his journey to India to procure Sanscrit books. Passing from Liang-cheu at the north-western extremity of China, he proceeded westward to the region watered by the Oxus and Jaxartes where the Turks 1 were then settled. He afterwards crossed the Hindoo-kush and proceeded into India. He lingered for a long time in the countries through which the Ganges flows, rich as they were in reminiscences and relics of primitive Buddhism. Then bending his steps to the southwards, he completed the tour of the Indian peninsula, returned across the Indus, and reached home in the sixteenth year after his departure. The same emperor, T‘ai-tsung, was still reigning, and he received the traveller with the utmost distinction. He spent the rest of his days in translating from the Sanscrit originals the Buddhist works he had brought with him from India. It was by imperial command that these translations were undertaken. The same emperor, T‘ai-tsung, received with equal favour the Syrian Christians, Alopen and his companions, who had arrived in A.D. 639, only seven years before Hiuen-tsang's return. The Histoire de la Vie de Hiouen-thsang, translated by M. Julien, is a volume full of interest for the history of Buddhism and Buddhist literature. As a preparation for the task, the accomplished translator added to his unrivalled knowledge of the Chinese language an extensive acquaintance with Sanscrit, acquired when he was already advanced in life, with this special object. Scarcely does the name of a place or a book occur in the narrative which he has not identified and given to the reader in its Sanscrit form. The book was originally written by two friends of Hiuen-tsang. It includes a specimen of Sanscrit grammar, exemplifying the declensions of nouns, with their eight cases and three numbers, the conjugation of the substantive verb, and other details. Hiuen-tsang remained five years in the monastery of Nalanda, on the banks of the Ganges, studying the language, and reading the Brahmanical literature as well as that of Buddhism.

Hiuen-tsang was summoned on his arrival to appear at court, and answer for his conduct, in leaving his country and undertaking so long a journey without the imperial permission. The emperor—praised by Gibbon as the Augustus of the East—was residing at Lo-yang, to which city the traveller proceeded. He had brought with him 115 grains of relics taken from Buddha's chair; a gold statue of Buddha, 3 feet 3 inches in height, with a transparent pedestal; a second, 3 feet 5 inches in height, and others of silver and carved in sandal-wood. His collection of Sanscrit books was very extensive. A sufficient conception of the voluminous contributions then made to Chinese literature from India will be obtained by enumerating some of the names.

Of the Great Development school, 124 Sutras.

On the Discipline and Philosophical works of the following schools:—

Shang-tso-pu (Sarvâstivâdas),

15

works.

San-mi-ti-pu (Sammitîyas),

15

„

Mi-sha-se-pu (Mahîshâshakas),

22

„

Kia-she-pi-ye-pu (Kâshyapîyas),

17

„

Fa-mi-pu (Dharmaguptas),

42

„

Shwo-i-tsie-yeu-pu (Sarvâstivâdas)

67

„

These works, amounting with others to 657, were carried by twenty-two horses.

The emperor, after listening to the traveller's account of what he had seen, commanded him to write a description of the Western countries, and the work called Ta-t‘ang-si-yü-ki was the result. 1

Hiuen-tsang went to Ch‘ang-an (Si-an-fu) to translate, and was assisted by twelve monks. Nine others were appointed to revise the composition. Some who had learned Sanscrit also joined him in the work. On presenting a series of translations to the emperor, he wrote a preface to them; and at the request of Hiuen-tsang issued an edict that five new monks should be received in every convent in the empire. The convents then amounted to 3716. The losses of Buddhism from the persecutions to which it had been exposed were thus repaired.

At the emperor's instance, Hiuen-tsang now corrected the translation of the celebrated Sutra Kin-kang-pat-nia-pa-la-mi-ta-king (in Sanscrit, Vajra-chedika-prajna-para-mita Sutra). Two words were added to the title which Kumarajiva had omitted. The new title read Neng-twan-kin, etc. The name of the city Shravasti was spelt with five characters instead of two. The new translation of this work did not supplant the old one—that of Kumarajiva. The latter is at the present day the most common, except the "Daily Prayers," of all books in the Buddhist temples and monasteries, and is in the hands of almost every monk.

This work contains the germ of the larger compilation Prajna paramita in one hundred and twenty volumes. The abstractions of Buddhist philosophy, which were afterwards ramified to such a formidable extent as these numbers indicate, are here found in their primary form probably, as they were taught by Shakyamuni himself. The translation of the larger work was not completed till A.D. 661. That Hiuen-tsang, as a translator, was a strong literalist, may be inferred from the fact, that when he was meditating on the propriety of imitating Kumarajiva, who omitted repetitions and superfluities, in so large a work as this, he was deterred by a dream from the idea, and resolved to give the one hundred and twenty volumes entire, in all their wearisome reiteration of metaphysical paradoxes.

Among the new orthographies that he introduced was that of Bi-ch‘u for Bi-k‘u, "Mendicant disciple," and of Ba-ga-vam instead of But for "Buddha." This spelling nearly coincides with that of the Nepaulese Sanscrit, Bhagavat. In the Pali versions he is called "Gautama," which is a patronymic, in Chinese, Go-dam. Ba-ga-vam is used in the Sutra Yo-sï-lieu-li-kwang-ju-lai-kung-te-king. Modern reprints of Hiuen-tsang's translation of the Shastras called Abhidharma, are found in a fragmentary and worm-eaten state in many of the larger Buddhist temples near Shanghai and elsewhere at the present time. He lived nineteen years after his return, and spent nearly the whole of that time in translating. He completed 740 works, in 1335 books. Among them were three works on Logic, viz., Li-men-lun, In-ming-lun, In-ming-shu-kiai. Among other works that he brought to China, were treatises on Grammar, Shing-ming-lun and Pe-ye-kie-la-nan, and a Lexicon, Abhidharma Kosha. 1

The modern Chinese editor of the "Description of Western Countries" complains of its author's superstition. Anxiety to detail every Buddhist wonder has been accompanied by neglect of the physical features of the countries that came under review. Here, says the critic, he cannot be compared with Ngai Ju-lio (Julius Aleni, one of the early Jesuits) in the Chih-fang-wai-ki (a well-known geographical work by that missionary). In truthfulness this work is not equal, he tells us, to the "Account of Buddhist kingdoms" by Fa-hien, but it is written in a style much more ornamental. The extensive knowledge, he adds, of Buddhist literature possessed by Hiuen - tsang himself, and the elegant style of his assistants, make the book interesting, so that, though it contains not a little that is false, the reader does not go to sleep over it.

The life and adventures of Hiuen-tsang have been made the basis of a long novel, which is universally read at the present time. It is called the Si-yeu-ki or Si-yeu-chen-ts‘euen. The writer, apparently a Tauist, makes unlimited use of the two mythologies—that of his own religion and that of his hero—as the machinery of his tale. He has invented a most eventful account of the birth of Hiuen-tsang. It might have been supposed that the wild romance of India was unsuited to the Chinese taste, but our author does not hesitate to adopt it. His readers become familiar with all those imaginary deities, whose figures they see in the Buddhist temples, as the ornaments of a fictitious narrative. The hero, in undertaking so distant and dangerous a journey to obtain the sacred books of Buddhism, and by translating them into his native tongue, to promote the spread of that superstition among his countrymen, is represented as the highest possible example of the excellence at which the Buddhist aims. The effort and the success that crowns it, are identified with the aspiration of the Tauist after the elixir of immortality; the hermit's elevation to the state of Buddha, and the translation of those whose hearts have been purified by meditation and retirement, to the abodes of the genii.

The sixth emperor of the T‘ang dynasty was too weak to rule. Wu, the emperor's mother, held the reins of power, and distinguished herself by her ability and by her cruelties.

In the year 690 a new Buddhist Sutra, the Ta-yün-king, "Great cloud Sutra," was presented to her. It stated that she was Maitreya, the Buddha that was to come, and the ruler of the Jambu continent. She ordered it to be circulated through the empire, and bestowed public offices on more than one Buddhist priest.

Early in the eighth century, the Confucianists made another effort to bring about a persecution of Buddhism. In 714, Yen Ts’ung argued that it was pernicious to the state, and appealed for proof to the early termination of those dynasties that had favoured it. In carrying out an edict then issued, more than 12,000 priests and nuns were obliged to return to the common world. Casting images, writing the sacred books, and building temples, were also forbidden.

At this time some priests are mentioned as holding public offices in the government. The historians animadvert on this circumstance, as one of the monstrosities accompanying a female reign.

About the beginning of the same century, Hindoos were employed to regulate the national calendar. The first mentioned is Gaudamara, whose method of calculation was called Kwang-tse-li, "The calendar of the bright house." It was used fur three years only. A better-known Buddhist astronomer of the same nation was Gaudamsiddha. By imperial command he translated from Sanscrit, the mode of astronomical calculation called Kien-chï-shu. It embraced the calculation of the moon's course and of eclipses. His calendar of this name was adopted for a few years, when it was followed in A.D. 721 by that of the well-known Yih-hing, a Chinese Buddhist priest, whose name holds a place in the first rank of the native astronomers. The translations of Gaudamsiddha are contained in the work called K‘ai-yuen-chan-king, a copy of which was discovered accidentally, in the latter part of the sixteenth century, inside an image of Buddha. It has been cut in wood more than once since that time. The part translated from Sanscrit is but a small portion of the work. The remainder is chiefly astrological. Among other things, there is a short notice of the Indian arithmetical notation, with its nine symbols and a dot for a cipher. There was nothing new in this to the countrymen of Confucius, so far as the principle of decimal notation was concerned; but it is interesting to us, whose ancestors did not obtain the Indian numerals till several centuries after this time. The Arabs learned them in the eighth century, and transmitted them slowly to Europe. Among the earlier Buddhist translations, a book is mentioned under the title of Brahmanical Astronomy," P‘o-lo-men-t‘ien-wen, in twenty chapters. It was translated in the sixth century by Daluchi, a native of the Maleya kingdom. Another is Ba-la-men-gih-ga-sien-jen-t‘ien-wen-shwo, "An Account of Astronomy by the Brahman Gigarishi." 1

The date of these translations, mentioned in the "History of the Sui dynasty," can be no later than the sixth century or very early in the seventh. The same should be observed of two works on Brahmanical arithmetic, viz., Ba-la-men-swan-fa and Ba-la-men-swan-king, each containing three chapters, and a third on the calculation of the calendar, Ba-la-men-yin-yang-swan-li, in one chapter. All these works, with one or two others given by the same authority, are now hopelessly lost, but the names as they stand in the history unattended by a word of comment, are an irrefragable testimony to the efforts made by the Hindoo Buddhists to diffuse the science and civilisation of their native land. The native mathematicians of the time may have obtained assistance from these sources, or from the numerous Indians who lived in China in the T‘ang dynasty. In the extant arithmetical books composed before the date of these works, examples of calculation are written perpendicularly, like any other writing, but in all later mathematical works they are presented to the eye as we ourselves write them from left to right. The principle by which figures are thus arranged as multiples of ten changing their value with their position, was known to the Chinese from the most ancient times. Their early mode of calculating by counters, imitated more recently in the common commercial abacus, was based on this principle. 1 But it does not appear that they employed it to express arithmetical processes in writing before the Hindoos began to translate mathematical treatises into the language.

The next notice of Buddhism in the history is after several decades of years. The emperor Su-tsung, in A.D. 760, showed his attachment for Buddhism by appointing a ceremonial for his birthday, according to the ritual of that religion. The service was performed in the palace, the inmates of which were made to personate the Buddhas and Bodhisattwas, while the courtiers worshipped round them in a ring.

The successor of this emperor, T‘ai-tsung, was still more devoted to the superstitions of Buddhism, and was seconded by his chief minister of state and the general of his army. A high stage for reciting the classics was erected by imperial command, and the "Sutra of the Benevolent King," Jen-wang-king, chanted there and explained by the priests.

This book was brought in a state carriage, with the same parade of attendant nobles and finery as in the case of the emperor leaving his palace. Two public buildings were ordered to be taken down to assist in the erection and decoration of a temple built by Yü Chau-shï, the general, and named Chang-king-sï. A remonstrance, prepared on the occasion by a Confucian mandarin, stated that the wise princes of antiquity secured prosperity by their good conduct—not by prayers and offerings. The imperial ear was deaf to such arguments. The reasoning of those who maintained that misfortune could be averted and happiness obtained by prayer was listened to with much more readiness. Tae-tsung maintained many monks, and believed that by propitiating the unseen powers who regulate the destinies of mankind, he could preserve his empire from danger at a less cost than that of the blood and treasure wasted on the battle-field. When his territory was invaded, he set his priests to chant their masses, and the barbarians retired. The Confucianist commentary in condemning the confidence thus placed in the prayers of the priests, remarks that to procure happiness or prevent misery after death, by prayers or any other means, is out of our power, and that the same is true of the present life. One of those who had great influence over the emperor was a Singhalese priest named "Amogha," Pu-k‘ung, 1 "Not empty," who held a high government office, and was honoured with the first title of the ancient Chinese nobility. Monasteries and monks now multiplied fast under the imperial favour. In the year 768, at the full moon of the seventh month, an offering bowl for feeding hungry ghosts was brought in state by the emperor's command from the palace, and presented to the Chang-king-sï temple. This is an allusion to a superstition still practised in the large Buddhist monasteries. Those who have been so unhappy as to be born into the class of ngo-kwei, or "hungry spirits," at the full moon of the seventh month, have their annual repast. The priests assemble, recite prayers for their benefit, and throw out rice to the four quarters of the world, as food for them. The ceremony is called Yü-lan-hwei (ulam), "the assembly for saving those who have been overturned." It is said to have been instituted by Shakyamuni, who directed Moginlin, one of his disciples, to make offerings for the benefit of his mother, she having become a ngo-kwei.

The emperor Hien-tsung, A.D. 819, sent mandarins to escort a bone of Buddha to the capital. He had been told that it was opened to view once in thirty years, and when this happened it was sure to be a peaceful and prosperous year. It was at Fung-siang fu, in Shen-si, and was to be reopened the next year, which would afford a good opportunity for bringing it to the palace. It was brought accordingly, and the mandarins, court ladies, and common people vied with each other in their admiration of the relic. All their fear was, lest they should not get a sight of it, or be too late in making their offerings.

On this occasion Han Yü, or Han Wen-kung, presented a strongly-worded remonstrance to the emperor, entitled Fo-ku-piau, "Memorial on the bone of Buddha." He was consequently degraded from his post as vice-president of the Board of punishments, and appointed to be prefect of Chau-cheu, in the province of Canton. A heavier punishment would have been awarded him, had not the courtiers represented the propriety of allowing liberty of speech, and succeeded in mitigating the imperial anger.

In this memorial he appealed first to antiquity, arguing that the empire was more prosperous and men's lives were longer before Buddhism was introduced than after. After the Han dynasty, when the Indian priests arrived, the dynasties all became perceptibly shorter in duration, and although Liang Wu-ti was on the throne thirty-eight years, he died, as was well known, from starvation, in a monastery to which he had retired for the third time. 1 The writer then pleads to Hien-tsung the example of his predecessor, the first Tang emperor, and the hope that he himself had awakened in the minds of the literati by his former restrictions on Buddhism, that he would tread in his steps. He had now commanded Buddha's bone to be escorted to the palace. This could not be because he himself was ensnared into the belief of Buddhism. It was only to gain the hearts of the people by professed reverence for that superstition. None who were wise and enlightened believed in any such thing. It was a foreign religion. The dress of the priests, the language of the books, the moral code, were all different from those of China. Why should a decayed bone, the filthy remains of a man who died so long before, be introduced to the imperial residence? He concluded by braving the vengeance of Buddha. If he had any power and could inflict any punishment, he was ready to bear it himself to its utmost extent. This memorial has ever since been a standard quotation with the Confucianists, when wishing to expose the pernicious effects of Buddhism. The boldness of its censures on the emperor's superstition, and the character of the writer as one who excelled in beauty of style, have secured it lasting popularity. Among the crowd of good authors whose names adorn the T‘ang dynasty, Han Wen-kung stands first of those who devoted themselves to prose composition. Christian natives in preaching to their countrymen often allude to this document.

Extraordinary superstition provoked extraordinary resistance. The sovereigns of the T‘ang dynasty were so fond of Buddhism that it has passed into a proverb. 2 the year 845 a third and very severe persecution befell the Buddhists. By an edict of the emperor Wu-tsung, 4600 monasteries were destroyed, with 40,000 smaller edifices. The property of the sect was confiscated, and used in the erection of buildings for the use of government functionaries. The copper of images and bells was devoted to casting cash. More than 260,000 priests and nuns were compelled to return to common employments. The monks of Wu-t‘ai, in Shan-si, near T'ai-yuen fu, fled to "Yen-cheu" (now Peking), in Pe-chi-li, where they were at first taken under the protection of the officer ill charge, but afterwards abandoned to the imperial indignation.

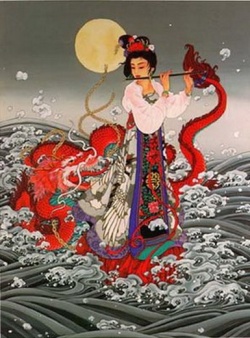

At this place there was a collection of five monasteries, constituting together the richest Buddhist establishment in the empire. There is a legend connected with this spot, which says that Manjusiri, one of the most celebrated of the secondary divinities of Buddhism, has frequently appeared in this mountain retreat, especially as an old man. By the Northern Buddhists "Manjusiri," Wen-shu-shï-li (in old Chinese, Men-ju-si-li), is scarcely less honoured than the equally fabulous Bodhisattwa, Kwan-shï-yin. The chief seat of his worship in China is the locality in Shan-si just alluded to, where he is regarded like P‘u-hien in Sï-ch‘wen and Kwan-yin at P‘u-to the Buddhist sacred island, as the tutelary deity of the region. Wen-shu p‘u-sa, as he is called, differs from his fellow Bodhisattwas in being spoken of in some Sutras as if he were an historical character. On this there hangs some doubt. His image is a common one in the temples of the sect.

The emperor Wu-tsung died a few months afterwards. Siuen-tsung, who followed him, commenced his reign by reversing the policy of his predecessor in reference to Buddhism. Eight monasteries were reared in the metropolis, and the people were again permitted to take the vows of celibacy and retirement from the world. Soon afterwards the edifices of idolatry that had been given over to destruction were commanded to be restored. The Confucian historian expresses a not very amiable regret at the shortness of the persecution. Those of the Wei and Cheu emperors had been continued for six and seven years, while in this case it was only for a year or two that the profession of Buddhism was made a public crime.

A memorial was presented to the emperor a few years after by Sun Tsiau, complaining that the support of the Buddhist monks was an intolerable burden on the people, and praying that the admission of new persons might be prohibited. The prayer was granted.