Accumulating merit and wisdom

accumulation and dedication of merit

(From the transcript The Two Accumulations: Merit and Wisdom, based on a teaching by Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche, revised)

At present, each of us is working toward success in our own life, a success measured in terms of experiencing pleasure as well as physical and mental wellbeing. Although that is everyone’s goal, some of us reach that goal while others, no matter how hard they try, do not. Instead of achieving happiness and wellbeing, they encounter illness and other unfavorable circumstances. Even though we may think that their inability to succeed is a result of lack of creativity, intelligence, and wisdom that is not the full explanation. The deeper reason is a lack of accumulation of merit. On the other hand, an individual who does experience success has these qualities of creativity, intelligence, and wisdom, but also has an accumulation of merit. The key factor for success is the accumulation itself.

The idea of wellbeing, happiness, and success can be explained by an example. If we want to cultivate crops, we need to know the right time to plant the seeds. If we plant the seeds during the right season, we will experience the result, the fruition, after the amount of time it takes the crops to grow. By virtue of hard work and appropriate timing, we will reap the appropriate harvest. In the same way, if we have accumulated merit in the past, we can experience fruition in our present life.

However, even if we know when to cultivate a crop, if we plant the seeds in the wrong type of soil, the crop will not be able to develop. Likewise, if we accumulate merit in the wrong way, while harboring negative thoughts, for example, we may have burned up the benefi cial results of the karma involved. To experience wellbeing in our lives, we need to have accumulated merit properly in our previous lives.

Even if we plant seeds in very fertile soil, if we burn them before planting, the fact that the ground is fertile will not make the burned seeds grow. Similarly, when we practice with impure motive, with neurotic thoughts, then we are like a farmer who burns the seeds before planting them in fertile soil. We will not be able to experience any benefi t from such accumulation. How the result of accumulation is experienced also depends upon an individual. Some are able to experience the outcome of their accumulations from past lives in this life. Some are able to experience the benefi t of proper accumulation from a particular lifetime later in that same life. It really depends upon the individual.

However, the main thing to bear in mind is that we are responsible for all of the accumulation, no matter when it occurred. We are the only one who experiences the goodness of our accumulation; the result is never lost.

It is also said that even a tiny virtuous accumulation can be great, just as by cultivating one seed, not one, but several grains result. As one seed can produce many grains, if we have accumulated even a small amount of merit with a pure motivation and a pure heart, the outcome can be great. Up until now, I have talked about accumulation in terms of wealth and success, which sounds very materialistic. However, accumulation is actually not a materialistic activity at all, and that is very important for a Dharma practitioner to understand. The accumulation of merit opens the door to the accumulation of wisdom; without it we would not have a way to develop wisdom. Therefore, accumulating merit is an essential part of our lives. The accumulation of merit helps us develop spiritual realization much quicker. A fully realized being is known as “one who has perfected the two accumulations.” Thus, in order to reach the full realization of buddhahood, we must accomplish the perfection of the accumulations. […] There are three objects of accumulation, which are known as superior, ordinary, and inferior. A superior or exalted object is one that is higher than we are, such as an enlightened being. An ordinary object is basically on the same level as we. The third object of accumulation is inferior beings —those who are totally caught up in pain, suffering, and struggle. As a result of this they suffer from constant fear. They are designated as inferior in the sense that they are to some degree helpless or powerless.

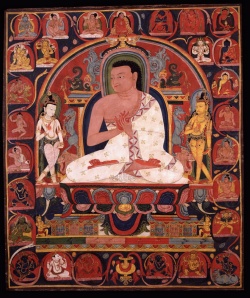

In Buddhism, the superior objects of accumulation are the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, also known as the Three Jewels. Making offerings, chanting mantras or sadhanas, and praising enlightened beings are all forms of accumulation through superior objects. Due to their limitless generosity, enlightened beings have supplied many emanations in tangible forms, in speech, and in other ways. This diversity of emanations enables us to accumulate merit by making offerings to images, reciting sadhanas, and so forth, to a variety of enlightened beings. Because the object of this accumulation is superior, we can experience the fruition of that accumulation more quickly and in limitless forms. […]

The second is an ordinary object of accumulation. In this case, the beings are quite ordinary, but out of gratitude we make them an object of accumulation. As you may know, in Buddhism we particularly thank our parents for their kindness.

Many people have been kind to us, but the ones who have been most kind to us are our own parents. In this particular generation of our society, when we talk about the kindness of our parents, many people fi nd it hard to accept. There is a lot of confl ict and alienation between parents and children. It is diffi cult for some of us to accept that our parents are indeed the kindest persons to whom we should be grateful. Because of our lack of knowledge regarding the bardo (the intermediate state after death and before rebirth), we do not understand what our parents have really done for us. In the absence of gratitude toward our parents, it is common in this generation for children to think that they are equal, and perhaps even superior, to their parents. Children are defi ant of their parents, and even take them to court and try to win legal judgments against them, which build up tremendous hatred. This is because they lack understanding of what sort of benefi t the parents have given them in bearing them and giving them human life. […]

The third type of object of accumulation is inferior beings. There are many who are experiencing a lack of food—in fact, starvation—as well as a lack of water to drink and proper clothing; there are many whose very lives are in jeopardy. If we try to protect them from the fear of loss of 2 3

To enhance your Dharma practice, Tsoknyi Rinpoche requested that a series of short papers based on his retreat teachings. The Teachings section on the main web site also contains a library of previously published materials and chants.

It is said that the path of enlightenment needs the accumulation of merit and wisdom to be complete, just as a bird needs two wings to fly. Merit is that which accumulates as a result of good actions and intentions, producing good karma that carries over to later in life or to the next life. Wisdom is transcendent knowledge through direct realization. Because western cultures prize intelligence, the wisdom aspect seems to dominate Dharma in the west, while the importance of accumulating merit remains little understood. The word merit itself in the context of Dharma is difficult for westerners to comprehend because in the west, merit seems to imply self-interest rather then preparation for benefiting other beings. Even the idea of accumulating merit through actions and intentions that form good karma is relatively new to the western world-view. However it is good karma that paves the way to bodhicitta, the enlightened heart/mind, which is the most profound outcome of Buddhist practice. Bodhicitta, like essence love, is always present in our basic nature. But it is obscured by our mundane way of thinking and veiled by deluded perception. So it’s no wonder that accumulating merit is a baffling notion to most western minds. But how do we begin to gain the needed openness, ease and balance to practice the accumulation of merit? We simply learn to practice the two types of merit.

Making Offerings, Supplications, Prayers and Dedicating the Merit

There are two types of offerings. One is in relation to the enlightened beings wherein we make offerings, supplications and prayers. It is through these that we establish a connection to enlightened beings and receive blessings. All phenomena, whether matter, mind or spirit have their own characteristics–their own energetic signatures. For instance, fire is hot and water is wet. The same applies to immaterial things, like the blessings of enlightened beings. The distinguishing characteristic of their spiritual influence is compassion, which is their energetic signature. We receive their compassion through the connection we establish with them. So by invoking Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, by reciting their mantras and making offerings, we connect with their energy and open ourselves to their spiritual influence.

Most of us can learn to recite mantras, but how to make offerings is not as obvious to western minds. Not having grown up in Tibet, it may seem a bit mysterious and inaccessible. But it really isn’t. We all know the feeling of being connected, and offerings are simply about connection, about opening to the energetic flow of blessings that comes through our connection with sublime beings. This connection is possible because these “beings” are no more substantial then we are or, for that matter, any other being in any realm–we’re all part of the same energy field. Within this field all beings have energetic patterns with particular energetic signatures, including sublime beings. We’re actually already connected through the resonance of energetic signatures within the matrix of being. We just have to open to this resonance, by atuning our minds. The atunement is possible through offerings, supplications and prayers so that we may receive the compassionate blessings of the sublime beings.

For an offering to be complete, there needs to be an object, an offering and intention.

The object can be the Three Jewels (Buddha, Dharma, Sangha) or the Three Roots (lama, yidam, protector).

The offerings are the five sense objects: forms, sounds, smells, tastes and textures or touchables. In addition we add two waters, so altogether there are seven offerings.

The intention is to be open to, connect with and appreciate the sublime beings’ compassionate blessings.

The way we make offerings is with care, love and affection. The offerings should be clean, our hands should be clean and the offerings arranged in a beautiful way. We never offer less then we have for ourselves. For example, when offering water, we offer nothing less then what we ourselves drink, be it spring water, purified water or mineral water. There is no limit to the amount of offerings that we may make; we can offer as much as we want or as much as we can afford. To make offerings we have to buy the material things we wish to offer. In order to buy the offerings, most of us have to work–money doesn’t just come without any effort. So it has meaning to spend money on the offerings to the sublime beings, and at the same time we are counteracting attachment. Offering whatever realization we may have is also appropriate. It cuts through any false pride we may harbor about ourselves as practitioners. Making sincere offerings of whatever we cling to opens the door to the flow of blessings. So no matter how large or small the offering, if we do it with a state of mind that is sincere and open-hearted, we can feel the offerings covering the whole sky. Then even a simple offering turns into the most exquisite, immense offering that you can imagine, and the connection is established.

However, you need effort, appreciation and generosity to make proper offerings. To make sure everything is the best you can afford, clean, and arranged beautifully–and to do this with mindfulness, non-attachment or ego-fixation and with regularity, so it is not so easy. But this is the whole point–offerings are not intended to be easy, but intended to open us to the blessings that flow from the sublime beings.

Here are some details about making offerings that might be helpful:

Use seven offering bowls and one butter lamp or candle, all placed the width of a rice grain apart. The best water we have can be used as symbolic offerings in each bowl. If using flowers and food, offer the most exquisite things available. Even if they’re common things, we use the best we can. These objects are placed in the bowls on a full bed of uncooked grain or, if you intend to throw it outdoors when the offering is removed from the shrine, on a bed of birdseed.

From left to right, the offerings represent:

Bowl 1. Drinking water: Pure water gathered from throughout the universe, endowed with eight qualities of being cool, sweet, light, soft, limpid, free of impurities, soothing to the stomach, and clearing to the throat.

Bowl 2. Washing water: Water as a symbol for cleansing and purification.

Bowl 3. Flowers: Including medicinal plants, fruits and grains.

Bowl 4. Incense: Including all natural and manufactured fragrances.

Between Bowl 4 and 5: A candle or butter lamp, representing all sources of illumination throughout the universe.

Bowl 5. Scented water: Including all perfumes and unguents.

Bowl 6. Food: Including all that is delicious to taste.

Bowl 7. Music: Including all naturally occurring or artificially produced sounds that are pleasant to hear.

To bring mindfulness to the offering practice and open the connection with the sublime beings, here are some prayers we can say while making the offerings:

While pouring water, we can recite, “A Verse for Making Water Offerings,” from Pure Vision, by Dudjom Lingpa: “This pool of nectar, endowed with eight qualities, is offered to the transcendent accomplished conquerors and their retinues. May they accept this so that I and all sentient beings may perfect the accumulations and purify the obscurations, so that this cyclic existence is dredged from its depths.”

If using fresh flowers, take a flower from the third offering bowl and sprinkle some water on the shrine, saying: “Ram, Yam, Kam” (fire, wind, water) one or more times. With this, all impurities are burned away by Ram; all impurities are blown away by Yam; all impurities are cleansed by Kam. You may also say this while sprinkling the water by hand.

Chant “Om Ah Hung” and feel that the offerings have been blessed and transformed into a huge quantity, as big as a mountain or filling the whole sky.

In the morning, these offerings are made before we take refuge in the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. After offerings and refuge we’re ready to practice. It can be sitting practice, chanting, a sadana or other practices. At the end of each session we dedicate the merit of the practice period, which makes the merit of the actions inexhaustible. Nagarjuna’s Dedication of Merit is the offering used in the Pundarika sangha:

Sonam diyi tamche zigpa nyi

Tobne nyepe dranam pam chene

Kye ga na shi balab trugpa yi

Sipe tsole drowa drolwar sho

By this merit may we obtain omniscience.

Having defeated the enemies, wrongdoings,

May we liberate all beings from the ocean of existence,

With its stormy waves of birth, old age, sickness and death.

At night we can remove everything from the shrine. Wash the cups, dry them with a clean cloth, and turn them over. If food is used, dispose of it by giving it away or throwing it away, but do not throw raw rice outdoors because it’s harmful to birds and animals that will eat it. There is no rule about changing everything everyday, but the more often the shrine offerings are changed the more merit, because merit is in the act and intention of offering, not in the objects themselves.

Worldly Attitudes and Actions

The second type of merit comes from our worldly attitudes and actions performed in a non-egocentric manner. These actions are beautifully expressed in Ordinary Refuge and Bodhicitta:

In the Buddha, the Dharma and the Supreme Sangha

I take refuge until enlightenment.

By the merit of practicing the paramitas,

May I attain Buddhahood for the benefit of all beings.

The paramitas are the virtues that can be perfected for the benefit of others. The western meaning of virtue is to do good things to please God, and upon death he accepts you into heaven. The result of virtue is making God happy to ensure your eternal happiness. In Buddhism, the focus is on the karmic results of your actions that have both material and immaterial consequences and these consequences shape your present and future lives. Karma is central to the consequences of all actions, virtuous and non-virtuous alike.

For example, if a man is extremely thirsty and you give him water with your ego piously doing something good, the man still quenches his thirst. It’s a good action and good karma comes from this because we’ve helped another person. Although it’s not particularly influential in achieving buddhahood, this kind of charity would still be considered accumulation of merit. So although it’s tainted by ego, it’s still important to do. Please keep doing it, because if we wait until we have a first class, non-egoic motivation, that motivation may not happen in time to quench the man’s thirst. Then the beneficial action does not happen. So even though there’s less then perfect motivation, still do it. Remember, people are not waiting for our motivation; they’re waiting for the tangible things they need.

Generally everything we give is tangible, material, isn’t it? We usually don’t think about giving something immaterial, but that’s what the Nangchen anis (nuns) give. What they give in a material way is zero, but they give so many immaterial things. They give love, they give courage, they give compassion and they give peace. To do this kind of giving, they have to have authentic, good motivation and so would we. That’s what people expect when receiving these immaterial things. What makes the Nangchen nuns’ giving so complete? It’s free of attachment. The material part of generosity itself isn’t capable of destroying attachment, just as compassion alone cannot do away with attachment. Nor can devotion or faith alone completely release attachment. What really cuts attachment is right view, which is the realization of the inherent emptiness of all phenomena. So unless one puts together the knowledge of emptiness with one’s altruistic actions, attachment will always be present. In this way, the practice of merit contributes to the realization of wisdom. And the practice of wisdom contributes to a better practice of merit. Compassion and the realization of emptiness really have to work together for maximum benefit, just like a bird needs its two wings to fly.

The need to balance merit with wisdom is not too hard to understand and very important to overall practice. What’s harder to see is the need to balance the focus of merit between current and future lives. Rebirth itself may be a difficult concept to wrap your mind around. Right now you may be thinking, “Okay, I’m already 40 (or 50, 60, or maybe more), so what can I expect of my Dharma practice? All I can expect is that it can help me in the years I have left before I die.” But that’s not the way to think. If we practice correctly with the time we have and accumulate a lot of merit and wisdom, these will continue into our future life. There’ll be a quick connection to the teachings in that life and everything will be easy for our practice of the Dharma. Actually, as practitioners it’s our responsibility and no one else’s to be the source of our future incarnation in which good, healthy Dharma can be born. So when we practice the accumulation of merit, it’s important that we have aspirations to continue our work as practitioners in the next life. Otherwise we’ll just practice with the shortsighted aim of only benefiting the years left in this life. There would be no projection into the future, and there would be no way to contribute to the next generation of ourselves in the future.

While balancing merit with wisdom is very important, so is balancing the focus of merit between current and future lives. There’s a danger of becoming a fundamentalist about merit, insisting that the benefits of practice are only for a future life, completely discarding any kind of influence on this life. But on the other hand, if one completely discards the importance of merit or blessings in the formation of future lives, then the benefits of the dharma are limited to this life alone. Both are forms of extremism and neither lead to the flowering of bodhicitta. So we practice the accumulation of merit for this life and future lives without attachment to the outcome, but with faith in the outcome. However, faith alone can also make an imbalance, a rigid extreme, and once again lead to fundamentalism. In Buddhism we do need faith and devotion, but it needs to be balanced with intelligence and compassion or it can become quite dangerous, inclining our intelligence to fundamentalism. So to prevent us from becoming a fundamentalist, we need to take care that our intelligence is neutral and balanced, not biased; that our faith in the outcome is balanced with loving kindness and compassion.

Finally, merit can only be understood once we’re able to verify it through our own experience. Until then, start right now to practice authentically, and don’t worry about the outcome in the future. The future always needs to start from a beginning, so make now the beginning, the birth of the enlightened attitude within us.

(copyright 2012 Pundarika Foundation)