Are We Prisoners of Shangrila?

Are We Prisoners of Shangrila?

Orientalism, Nationalism, and the Study of Tibet

by Georges Dreyfus, Williams College

Abstract: This essay examines the consequences of Said’s critique of orientalism for Tibetan studies, particularly in relation to Lopez’s claim that we are all “prisoners of Shangrila.” The paper takes up this critique in relation to Lopez’s treatment of the present Dalai Lama, arguing that although his critique is useful, it exaggerates the scope and power of orientalism, and in the process ends up de-historicizing and reifying Tibetan culture into a closed totality that either remains unchanged or becomes debased through the intervention of the West. This, the essay argues, leaves little room for alternatives to orientalism, both in the West and among Tibetans, and thus ends up repeating the exclusionary gesture that this critique had sought to debunk.

Introduction

There is no need to extol the importance of Edward Said’s Orientalism for the study of Asian cultures in the contemporary world.1 Even the rather conservative discipline of Buddhist Studies bears the mark of the critique inaugurated by Said.2 In recent years, this critique has been directed toward the study of Tibetan culture and its appropriation by the West, chiefly through the work of Donald Lopez and his Prisoners of Shangrila.3 Lopez lucidly applies Said’s insights (as well as those of Foucault and Bourdieu) to analyze the ways in which Tibet has been appropriated in Western culture. Although Prisoners has been discussed in several forums,4 I believe that a further assessment of this work can be helpful for conceptualizing [page 2] the role of the critique of orientalism in the study of Tibetan culture and the alternatives that such critique may open.

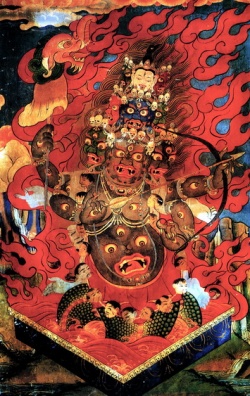

Lopez’s main thesis, which is well known, is that Tibet has long been the object of Western fantasy, and it is this that largely explains its particular impact on the contemporary West. For Lopez, Tibet as it is understood in the West is less a country with its own history and socio-cultural arrangements than a construction, a mythical hyper-reality created by and for Westerners. As such, Tibet is subject to the play of binary oppositions. Either it is the holy land, the repository of all wisdom, the idyllic society devoted to the practice of Buddhism, or it is the land of all superstitions, a cesspool of medieval corruptions, an abominable theocratic regime based on the monstrous exploitation of serfs. For Lopez, the continuous currency of these conflicting stereotypes signals the enduring status of Tibet as an object of fantasy.

At the outset, let me make clear that I have little problem with this thesis, which I find it difficult to argue against. As an exploration of the ways in which the West has constructed Tibet, Prisoners of Shangrila is valuable. It is a useful inventory of some of the orientalist archives through which Tibetan realities continue to be interpreted. It sheds light on some of the reasons why Tibet as a mythological hyper-reality persists, and why it continues to circulate unchallenged. It explores some of the ways in which, to paraphrase Said,5 Tibet has been Tibetanized; that is, created into this object of fantasy that I encounter among my students, on the Web and by now in shopping malls as well. This is in fact the main object of Lopez’s book, which explores the orientalist archives and explains the surprisingly long-lasting hold of these archives on the contemporary imagination. Such an exploration is important for those of us whose lives intersect in complicated ways with the often tragic fate of Tibetans.

I have also no objection to another related goal of Lopez’s book, the attempt to rescue the Tibetan cause from the over-enthusiastic reactivation of the myth of Shangrila, the idealization of Tibet as “a happy, peaceful people devoted to the practice of Buddhism whose remote and ecologically enlightened land, ruled by a god-king, was invaded by the force of evil.”6 Lopez argues that this view is harmful for the cause of Tibetan independence, which should be argued for on different grounds. Propping up Tibet as an ideal society marginalizes Tibet, threatening to remove this country from the arena of real political action so as to enshrine it in a realm of pure ideals and fantasies.

The aspect of Lopez’s work I wish to take issue with concerns the extent of the regime of representations that he analyzes, the striking claim that “we are all [page 3] prisoners of Shangrila.”7 Such a claim, which resonates with the title of the book, strikes me as problematic in more than one respect, and I wish to investigate the questions that it raises. I believe that these issues are important not just for the study of Tibet and its culture, but also for understanding how the critique of orientalism intersects with Asian cultures generally.

[1] Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary (Springfield: Merriam-Webster, 1986), 832. See also Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage, 1979), 51, 73.

[2] Donald S. Lopez, Jr., Curators of the Buddha (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

[3] Donald S. Lopez, Jr., Prisoners of Shangrila: Tibetan Buddhism and the West (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

[4] See, for example, the symposium on Donald S. Lopez’s Prisoners of Shangrila in Journal of the American Academy of Religion 69, no. 1 (2001): 163-213.

[5] For Said, the Orient as studied by Orientalists is not just some part of the world “out there,” waiting to be discovered and studied. Rather, it is a cultural construction constituted by certain discourses, orientalism, that separate the West from Asia by focusing on the latter’s odd and unusual traits, customs, and habits. In this way, the Orient is constructed – or to use Said’s formulation, the Orient is “orientalized” – as the object to be represented and controlled by the West, the foil against which the West can identify itself as different and intrinsically superior (Said, Orientalism, 5).

[6] Lopez, Prisoners, 10.

[7] Lopez, Prisoners, 13.

Archive or Prison?

Lopez’s claim that we are all prisoners raises several questions. The first and obvious question is this: who is the “we” Lopez is referring to? The answer to this question appears to be surprisingly broad. Lopez does not mean to exclude himself, and claims that he and his work too are prisoners of Shangrila. I am not sure how to take this disclaimer, how to understand Lopez’s statement that “[t]his book is not written outside the walls of the prison, nor does it hold a key that would permit escape.”8 Is such a claim the modern equivalent of the subduing of pride (kengpa kyungwa), the rhetorical device often used by Indian and Tibetan authors to claim authority in accordance with socially prescribed modesty? More seriously, this claim connects to the important issue concerning the nature and purview of orientalist representations, raising questions such as: Does the orientalist discourse constitute an all-pervading epistemic regime impossible to escape? Is it really appropriate to compare a culture to a prison, particularly in the cross-cultural context that concerns us here?

These are important questions to which I will return at the end of this essay. For the time being, I wish to raise another important question that concerns the possibility of alternatives to the dominant orientalist discourse. It is clear that Lopez intends to focus on Western representations, and thus it is not surprising that he wishes to include in the prison of representations the people who share in the culture that has produced these representations. But what about Tibetans? Are they too prisoners of Shangrila? This is the question I wish to explore here first.

In the last chapter of his book, suggestively entitled “The Prison,” Lopez seems to answer with a resounding and rather sweeping “yes.” The prison of orientalist representations includes not just us Westerners – naive romanticizers or sophisticated academics like Lopez and his “friends,” Jeffrey Hopkins, Robert Thurman, and others – but even Tibetans, including the present Dalai Lama. To make his case, Lopez examines elements of the Dalai Lama’s writings in order to demonstrate how they connect with orientalist fantasies. In making this connection (to which I will return) Lopez is suggesting, if I understand him correctly, that the Dalai Lama is also a prisoner of Shangrila, that his ideas are less the expressions of the Buddhist tradition than reenactments of orientalist fantasies. This claim is rather dramatic, and in my opinion mistaken. Nevertheless, it is interesting and not unwelcome, providing us with the opportunity to engage Lopez’s arguments and explore the important issues that lie behind his claim. Lopez builds his case [page 4] by analyzing the Dalai Lama’s thought in connection to two related notions, Buddhist modernism and nationalism.

Buddhist modernism refers to an understanding of Buddhism developed first in the Buddhist (mostly Theravāda) world at the end of the nineteenth century as a reaction to Western domination. Originally, Buddhist modernism sought to respond to the negative colonial portrayal of Buddhism by presenting its tradition in modern and positive terms. Within this discourse, Buddhism is in some respects depicted as a world religion on a par with other world religions, particularly Christianity: having its own founder, sacred scriptures, philosophical tradition, etc. But in other respects Buddhism is not considered as being just on a par with other religions, it is in many ways superior to them. Buddhism, it is claimed, is based on reason and experience and does not presuppose any blind acceptance of authority. As such, it is highly compatible with modern science, to whose authority it appeals. It is also a religion, if it can be so called, aimed solely at providing its followers with a path leading to the overcoming of suffering. As such, this path is strongly ethical (e.g., devoted to non-violence), and provides valuable resources for social action. The practice that it recommends is meditation, which is extolled over and above ritual, which in turn is devalued as popular superstition.9

As one can notice, this description fits quite well the belief system of many contemporary Buddhists. It also resonates well with some of the ideas of the Dalai Lama, whom Lopez describes as “the leading proponent of Buddhist modernism.”10 For example, the Dalai Lama advocates non-violence following Gandhi’s example; he participates in inter-faith dialogues; and takes a strong interest in encounters with scientists. All of this is quite true. The Dalai Lama certainly has strong leanings toward Buddhist modernism, and many of his actions exemplify this ethos. But Lopez is not happy just to demonstrate a connection between this modernist stance and some of the Dalai Lama’s ideas, a connection that is hard to deny. He wants to assert that this link shows the degree to which the Dalai Lama has internalized the orientalist discourse, or, to put it in Lopez’s terms, the extent to which he is a prisoner of Shangrila.

To make his point, Lopez draws several connections that I believe are problematic. The first is that between the Dalai Lama’s modernism and his rejection of the protector Shukden. For Lopez, the Dalai Lama’s rejection of Shukden, which has led to what I have called the “Shukden affair,” is an attempt to take Tibetans out of their clan identities towards a national affiliation. Within this perspective, the followers of Shukden are said to represent the ancestral and native tradition opposed to the Dalai Lama’s modernist attempt to reform the Geluk tradition.11 Lopez then proceeds to show the background of this attempt at [page 5] modernization, which is the lack of Tibetan national consciousness prior to the exile of 1959. Before that date Tibetans had a sense of collective identity derived from their cultural mores (e.g., eating tsampa – roasted barley flour) and regional affiliations, but lacked any true sense of nationalism. It is only after 1959 that Tibetans began to develop an awareness of themselves as a nation. This coincided, however, with Tibetan contact with orientalist representations, and this proximity has fatally infected the whole process. Lopez explains:

Introduced by Western supporters to the notion of culture, Tibetan refugees could look back at what Tibet had been. But this gaze, at least as it was represented to the West, saw the Land of Snows only as it was reflected in the elaborately framed mirror of Western fantasies about Tibet. It was only through this mirror, this process of doubling, that a Tibetan nation could be represented as unified, complete and coherent. It was as if a double of Tibet had long haunted the West, and the Tibetans, coming out of Tibet, were now confronted with this double.12

Tibetans, who lacked any sense of national identity, were faced with the necessity of representing themselves to Westerners. In order to do so, they chose to use the only vocabulary that was available to them, the one offered by Western lay or scholarly orientalists. For Lopez this is particularly true of the Dalai Lama, who often functions as a spokesperson for Tibet. As such he has offered a beatific version of Tibet according to which the essence of Tibetan culture is Buddhism, and the essence of Buddhism is compassion. But this vision of Tibet, which is actually more Indian than Tibetan, reflects poorly the actual complexity of Tibetan Buddhism, which contains many ideas and practices besides compassion (such as the propitiation of Shukden).

Moreover, this vision of Tibet has, according to Lopez, the serious disadvantage of being free-floating. As Lopez puts it, “it is unclear, however, why there must be a political entity called Tibet in order for this inheritance to be transferred.”13 In fact, instead of committing himself to the particularity of the nation-state, the Dalai Lama espouses a view of Tibet as a zone of peace, a neutral and disarmed place open to the rest of humanity. For Lopez, this vision of Tibet is little more than a reenactment of the Western orientalist fantasies that have inhabited the West and colonized the rest of the world. Lopez states, referring to the Dalai Lama’s vision of Tibet:

What seems inevitable, however, is the way in which his proposals appear to blend seamlessly with the pre- and post-diaspora fantasies of Tibet as a place unlike any other on the globe, a zone of peace, free of weapons that harm humans and the environment, where the practice of compassion is preserved for the good of humanity.14

Lopez then goes on to accuse the Dalai Lama of sacrificing the building of Tibet as a nation-state – sacrificing it, that is, to his vision of Tibet as a zone of peace, making “Tibet a surrogate state, a fantasy for the spiritualist desires of non-Tibetans, desires that have remained remarkably consistent during the past century, as evinced by the string of quotations from Master Koot Hoomi (the alleged hidden master of the Theosophists) to Richard Gere.”15

In the following pages I address some of Lopez’s more important points, particularly those that are germane to a discussion of the intersection of the critique of orientalism and the Tibetan situation. I argue that the description of the Dalai Lama as a victim of orientalist fantasies over-simplifies a situation that is vastly more complex. I also suggest that the description of Tibetan nationalism as an internalization of Western fantasies of Tibet is markedly ahistorical, glossing over the process through which this nationalism emerged.

[8] Lopez, Prisoners, 13.

[9] This brief account follows Lopez’s summary (Prisoners, 185) as well as H. Bechert, “Buddhist Revival in East and West,” in The World of Buddhism, eds. H. Bechert and R. Gombrich (London: Thames and Hudson, 1984), 275-76.

[10] Lopez, Prisoners, 185.

[11] Lopez, Prisoners, 196.

[12] Lopez, Prisoners, 200.

[13] Lopez, Prisoners, 200.

[14] Lopez, Prisoners, 205.

[15] Lopez, Prisoners, 206.

The Shukden Affair and Buddhist Modernism

To start with, I disagree with Lopez’s interpretation of the Shukden affair as an opposition between clan-based and modernist interpretations of the tradition. First, as I have shown elsewhere,16 the propitiation of Shukden as a Geluk protector is not an ancestral tradition, but a relatively recent invention of tradition associated with the revival movement within the Geluk spearheaded by Pabongkha (1878-1941). Second, in this dispute the Dalai Lama’s position does not stem from his Buddhist modernism and from a desire to develop a modern nationalism, but from his commitment to another protector, Nechung, who is said to resent Shukden. Thus, this dispute is not between followers of a traditional popular cult and a modernist reformer who tries to discredit this cult by appealing to modern criteria of rationality. Rather, it is between two traditional or clan-based interpretations of the Geluk tradition, that of Shukden’s followers who want to set the Geluk tradition apart from others, and the Dalai Lama’s more eclectic vision. The fact that the former may be more exclusivistic and that the latter may be more open does not entail that they can be interpreted adequately through the traditional/modern opposition.

The stance taken by the present Dalai Lama in the Shukden affair is interesting for our purpose, for it throws some light on the role of Buddhist modernism in his thinking. To describe the Dalai Lama as a Buddhist modernist is in fact only partly true. This description captures neither the complexity of his positions nor the way in which his ideas have evolved. There is no doubt that the Dalai Lama has been strongly influenced by Buddhist modernism, but I would argue that he is himself, at least in the last twenty-five years (since the beginning of the Shukden affair), not a typical Buddhist modernist. Very little has been written about his intellectual evolution. To understand him, one is reduced to looking at his writings, his [page 7] authorized autobiography, and the scraps of information that can be gathered from witnesses. When one does this, I believe that the following picture emerges.

As we all know, the present Dalai Lama was educated in a very traditional Buddhist fashion, mostly according to the curriculum of the great Geluk monastic universities. The Dalai Lama himself has remarked how this education was unbalanced and inappropriate to the modern world, particularly for a person who had to assume a leadership role.17 As a result of this education, the Dalai Lama was completely unprepared to face the modern world, which came crashing down on him in 1950. Confronted with this weighty responsibility, the Dalai Lama tried to cope with the situation, learning on the job, as it were, how to deal with the modern world. First, his dealings with the Chinese were obvious “occasions” for such learning. Particularly important was his trip to China in 1954-55. His encounter with Chairman Mao made a lasting impression on the young Dalai Lama, as did his visit to Chinese factories. The most formative encounters, however, took place in India, a country that the Dalai Lama visited extensively in 1956 before settling there more permanently in 1959.

All this is well known. What is perhaps less appreciated is the degree to which these early years spent in India were formative of the Dalai Lama’s stance toward modernity. There, the Dalai Lama encountered people he could identify with. Nehru made an obvious impression, but probably more important were other less famous figures (such as the then-President of India Rajendra Prasad, Jayaprakash Narayan, Acharya Tulsi, etc.), who barely figure in the authorized biography. I believe that these people were significant for the Dalai Lama’s formation, for they showed him through their own versions of modernism (Hindu or Jain) how one could be a religious person and yet a full participant in the modern world. It is in large part as a result of contact with these men that the Dalai Lama seems to have developed his own Buddhist modernism as a position adapted to modernity and yet in agreement with his traditional background.

What is worth noting here is that the role of Westerners in these formative years seems to have been minimal, mostly limited to practical matters. It is only with his meeting with Thomas Merton at the end of 1968 that the Dalai Lama began to be influenced directly by Western ideas. But by then, his particular form of Buddhist modernism was in large part already formed. Thus, it is quite mistaken to represent him as suddenly captured by Western fantasies, for his views were formed more through contact with Indian ideas than with Western ones.

Of course, these Indian ideas were themselves products of a complex interaction between Indian culture and the Western worldviews of colonialism. Even this interaction cannot be described, however, as a simple process of internalization of Western ideas by Indians. What must be factored into this process is the role that traditional Indian ideas played, and the ways in which Indians have been able to combine these ideas with modern views. Using the insights of Memmi, Fanon, Mannoni, Césaire, and other thinkers who have charted the psychology of [page 8] colonization and the difficulties of liberation, Ashis Nandy has described the process as a complex interaction that has evolved over time.18 In India, the process started during the nineteenth century with a high degree of internalization of colonial stereotypes, but gradually moved toward more hybrid products in which the colonized were able to develop an identity that was at the same time modern and yet profoundly Indian. For Nandy, Gandhi – who puts forth his own synthesis of traditional Indian attitudes and Western ideas – is the decisive figure who manages to undermine the colonizer’s authority.

For Nandy, Gandhi’s greatness consisted of his ability to deconstruct colonial stereotypes through which the colonizers had justified their rule. Instead of trying to beat the British on their own ground, Gandhi rejected the gender identification between the colonizer, masculinity, and its alleged virtues (strength, courage, maturity), and instead turned to saintliness as the ideal through which he was able to mobilize traditional notions of the connection between the feminine and power (Skt. śakti). In this way, according to Nandy, Gandhi was able to overturn the disempowering colonial stereotypes and to provide a new stance for modern Indians. This stance was simultaneously in touch with traditional ideas – and hence was able to rally the still largely traditional Indian villagers – and yet was also profoundly modern. Whether or not we agree with all the details of Nandy’s analysis, the complexity of the process through which Gandhi’s Hindu modernism was formed is clear. Hindu modernism is not a simple internalization of orientalist fantasies, but a complex synthesis in which traditional Indian ideas interact with a variety of Western ideas such as orientalist understanding of Hinduism, Christian attitudes toward religion, modern Western political culture, etc.

It is these ideas that the Dalai Lama encountered in India in the first years of his exile. They apparently influenced him greatly, and still largely shape his interactions with modernity. They also led him to take fairly radical positions within the Tibetan community. For example, the Dalai Lama insisted that the community in exile adopt, despite the opposition of the majority of his own people, a constitution in which the Dalai Lama’s role was limited and could be submitted to democratic oversight. It is also these modernist ideas that led him to take unconventional positions within the Tibetan religious universe. Particularly important in this regard has been his avowed distrust of the institution of the reincarnated lama. It would be a mistake, however, to overemphasize the role of Buddhist modernism within the Dalai Lama’s overall intellectual trajectory.

The Dalai Lama’s encounter with modernity did not lead him to repudiate his traditional background. For example, the Dalai Lama never embraced the distrust of ritual, one of the hallmarks of Buddhist and Hindu modernisms. In many respects, he remained a person deeply imbued with traditional Tibetan values and attitudes. I also believe that the Dalai Lama underwent an evolution that has not been noticed by most observers. Living in Dharamsala in the 1970s and 1980s, I was able to observe some of the changes that he underwent. When I first met him at the [page 9] beginning of the seventies I was struck by his unconventional ideas, his willingness to relativize and even discard aspects of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. This radical stance changed to a more traditional one, however, during that same decade. I believe that this change can be traced back to the winter of 1975-76, a time during which the Dalai Lama undertook an important retreat. The Dalai Lama has never explained what happened during this retreat, but my guess is that he had several experiences, visions, or dreams concerning the Fifth Dalai Lama’s visionary teachings, which he had received as a child in Tibet. In his authorized biography, the Dalai Lama makes only this cryptic comment:

Also, at around this time [1947, the time of the Reting affair] I received from Tathag Rinpoché the special teachings of the Fifth Dalai Lama, which is considered particular to the Dalai Lama himself. It was received by the Great Fifth...in a vision. In the following weeks, I had a number of unusual experiences, particularly in the form of dreams, which although they did not seem significant then, I now see as being very important.19

My own speculation is that the last sentence of this statement refers to the change of attitude toward the Great Fifth and his visionary teachings that took place during the winter of 1975-76. It was as the result of this, it seems to me, that the Dalai Lama came to reevaluate his relation to the Fifth Dalai Lama, to the institution of the Dalai Lama, and more generally to his tradition as a whole. It is also at that time that the Dalai Lama began his offensive against the practice of Shukden by refusing the long-life offering that the government customarily makes after the new year.20 Thus, far from being an expression of his modernism, his opposition to Shukden is motivated by his return to a more traditional stance in which this deity is seen as incompatible with the vision of the tradition (the “clan”) represented by the Fifth Dalai Lama.

This return to a more conservative stance did not entail a repudiation of Buddhist modernism, which remained his favored way of interacting with more strictly modern contexts, particularly with the West, which he started to visit seriously only at the end of the seventies when he was well over forty. During these later interactions, the Dalai Lama began to be interested in ecumenical exchanges and in environmentalism, concerns that were new to him at that time. These new interests brought very few changes to his overall orientation, which is expressed in the messages that he has delivered during his numerous tours.

As one can see from this brief account of the intellectual evolution of the Dalai Lama, his ideas are far from being simple appropriations of Western fantasies. Certainly, they have been influenced by the orientalist perceptions of Buddhism which had an important role in the emergence of Buddhist modernism. It is also clear, however, that his ideas and Buddhist modernism in general are not simply the reflections of orientalist discourse. They constitute an interpretation of the [page 10] Buddhist tradition which is certainly modern and hence new, but which is nevertheless well grounded in the tradition. After all, the ideas that Buddhism has a founder, a body of sacred scriptures, and a sophisticated philosophical tradition are all important elements of Buddhist tradition. Similarly, the idea that meditation is a central practice is not a complete innovation. Its extension to the laity and to the monastic population as a whole is certainly new, but its central normative role is not. Even the elements of Buddhist modernism that are least grounded in the tradition, such as its compatibility with scientific thinking, do tap into long-standing trends of the tradition. The Buddha’s recommendation that one should investigate the teachings before adopting them – like testing gold before one buys it – is not, after all, a modern creation!

[16] Georges Dreyfus, “The Shukden Affair: History and Nature of a Quarrel,” Journal of International Association of Buddhist Studies 21, no. 2 (1999): 227-70.

[17] The Dalai Lama, Freedom in Exile (New York: Harper, 1990), 25.

[18] Ashis Nandy, The Intimate Enemy (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983).

[19] The Dalai Lama, Freedom in Exile, 31. My brackets.

[20] For more details on this episode, see Dreyfus, “The Shukden Affair.”

Tibetan Religious Nationalism

Similarly, the depiction of Tibetans as emerging on the world scene in 1959 without any national self-consciousness only to be captured by Western fantasies distorts a situation that is vastly more complex than the unidirectional influence suggested by Lopez. Such a description is markedly ahistorical, reducing the complex developments through which Tibetan nationalism emerged to a few contemporary events.

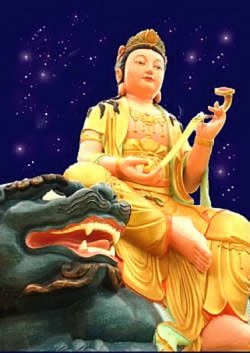

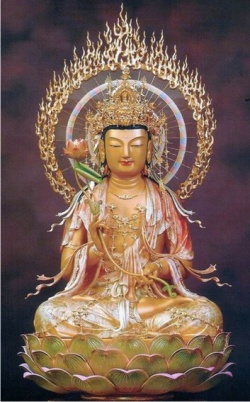

It is true that to a large extent Tibetans did not have a full-fledged nationalism before 1950.21 But this does not mean that prior to 1950 Tibetans did not have any sense of themselves as belonging to a country. As I have argued elsewhere,22 at least in central Tibet since the thirteenth or fourteenth century Tibetans understood themselves as belonging to a country defined in terms of the shared memories articulated by some of the more important treasures (terma) such as the Mani Kabum, etc.23 These narratives identify Tibet as an originally barbarous country [page 11] civilized by Buddhism and transformed into the pure land surrounded by snow mountains often referred to in Tibetan prayers. This transformation was brought about by the beneficent activities of Avalokiteśvara during his periodic manifestations throughout Tibetan history as Songtsen Gampo, Padmasambhava, Atiśa, and later the Dalai Lamas. In the Mani Kabum, Avalokiteśvara is described as the deity with whom Tibetans have a special relation. He is the progenitor of the Tibetan race, and he comes to the aid of Tibet throughout its history.

Such a sense of collective identity – which I have described, following Hobsbawn, as proto-nationalism24 – differs from a full-blown modern nationalism. Nevertheless, it prefigures nationalism in several ways, and explains the ease with which Tibetans have stepped into nationalist modernity. This transition, which remains to be explored fully but has started to be documented in Tsering Shakya’s excellent work,25 took place during the 1950s, and owes little to Western influence. Perhaps one of the first manifestations of modern nationalism in Tibet was the formation in 1954 of People’s Committees (mimang tsokdu) among low-ranking officials and traders (members of the kind of middle class among whom nationalism often develops). This movement of protest against the Chinese occupation was in part motivated by the realization that the ruling elites had failed to confront the Chinese, and by the desire to oppose the Chinese occupation more directly. The activity of these committees was an interesting blend of traditional worship of local deities, anti-Chinese protests, and attempts to develop institutions such as the army and the mint.26 The effects of this movement remained limited, though it contributed to the later rise of a resistance movement.

A second, more significant step in the formation of Tibetan nationalism was the creation of the Four Rivers, Six Ranges (chuzhi gangdruk) movement against the Chinese occupation. Shaken by the events taking place in Kham, and the bad omens reported throughout Tibet, a group of traders from Kham living in Lhasa decided to collect funds from all over Tibet to offer a golden throne to the Dalai Lama. On the fourth of July, 1957, the ceremony took place in the Norbu Lingka in Lhasa, where a large number of people came together to express [page 12] their allegiance to their leader and their defiance of the Chinese.27 Offering a golden throne to the Dalai Lama was seen as a way of expressing and strengthening the bond between the Tibetans and their leader. It was an attempt to reaffirm the power of the Dalai Lama over the land of Tibet, a land that according to traditional Tibetan narratives belonged to him by virtue of his being a manifestation of Avalokiteśvara. Finally, this act was also an act of opposition to the Chinese occupation, perceived as the action of the enemies of Buddhism (tendra), the beings that are to be eliminated by the dharma-protectors.

This date, the fourth of July 1957, can be seen retrospectively as marking the birth of Tibetan nationalism, the awareness that Tibetans have of belonging to a single country. The offering of a throne, a traditional symbol of religious authority, was a way for Tibetans to affirm their allegiance to the entity thus defined. Shortly after, the Four Rivers, Six Ranges was constituted formally as a movement of resistance to the Chinese occupation, thus transforming the local uprisings in Kham into a nationalist struggle encompassing central Tibet as well as eastern Tibet. This in turn led to the uprising in March of 1959, and to the tragic events that followed, which sealed the national awareness developed during the 1950s.

The nationalism that emerged during this period is characterized by its use of traditional religious themes to define the nation. Instead of using the secular discourse usually associated with modern nationalism, this brand of nationalism defines the Tibetan nation by using traditional Buddhist values such as compassion, karma, and the bond between Tibetans and Avalokiteśvara. The nation thus defined is not, however, traditional Tibet with its diversity of local cultural, social, and political communities, but a modern country united by its opposition to Chinese oppression.28 Such a country is conceived as a horizontal community determined by boundaries, a reified entity to which all its members owe equal allegiance irrespective of their local affiliations. Hence, it is a nation-state and the loyalty toward such an entity is a form of modern nationalism, with all the potential dangers that this implies.

The religious character of such a nationalism is well captured by the anthems used by Tibetans in exile to express their national aspirations, the Prayer of Truthful Words (dentsik mönlam) and the National Anthem.29 A particularity of both these songs, which are still in use by Tibetans in exile during celebrations [page 13] such as “March Tenth,” is that they are modeled after traditional religious prayers. As such, they contain traditional Buddhist motives such as the prayer for the continuation of the Buddhist teaching, and the request to the Buddhas and bodhisattvas to help the beings who are tormented by the unbearable suffering of karma. These anthems are not, however, just prayers. They also express political concerns, as when the author of the Prayer of Truthful Words refers to “the spiritual people of the Land of Snow who are being eliminated through every torture and tyranny by the barbarism of destructive forces lacking loving kindness.” This clear reference to the actions of the PRC in Tibet expresses the nationalist opposition to Chinese occupation. And yet, the song never departs from a religious idiom, going on to say that these actions should not be seen through anger but with compassion. The people who destroy Tibet should be considered objects of compassion rather than of anger, says the song. Nevertheless, this compassion is not without political content, since it is the basis for “the complete independence of Tibet in its entirety, the only goal that can satisfy the Tibetan people.” The song continues with a request to Avalokiteśvara, the patron bodhisattva of Tibet, to “take care of those who will give up their bodies and will undergo hardships for this goal.” It ends with an invocation to truth so that these prayers can be realized.

I should make it clear here that I do not believe that stressing the role of Buddhist themes in the formation of this form of Tibetan nationalism necessarily dooms one to participation in the mystification of Tibet as defined by some unique spiritual essence that sets it apart from the rest of humanity. Nor do I mean to suggest that Tibetans in their national struggle are high-minded, though they often are. Finally, this analysis is not intended to capture Tibetan nationalism as a whole, for it is limited to one particular form of nationalism, the one advocated by the Dalai Lama. This national vision has been adopted by many Tibetans, both inside and outside of Tibet, but it is certainly not the only one. Tibetan nationalism is not a unified discourse, but a site of contention, where conflicting visions compete for the allegiance of Tibetans. There are many Tibetan nationalists, both inside and outside of Tibet, who are markedly uncomfortable with religious nationalism and who feel ill at ease to self-identify with the moral community defined by the Prayer of Truthful Words and the National Anthem. They argue that Buddhism should not have much of a role to play in Tibetan political institutions, and that the predicament of Tibet is largely due to Buddhism and its non-violent message, which they see as a possibly fatal liability for the future of Tibet. Such a stance has been expressed with great force in some of the literature that has come out of Tibet, particularly out of Amdo, in the last two decades. This nationalism is certainly important for the future of Tibet, and I do not wish to suggest in any way that it is somehow less authentically Tibetan than the kind of religious nationalism I am analyzing here. I do wish to emphasize, however, that the Tibetan national awareness displayed by these anthems owes very little to Western ideas. It is traditional Buddhist ideas rather than orientalist fantasies that were pivotal to the emergence of Tibetan national awareness.

The nature of this religious nationalism was further inflected by the experiences of Tibetan people both inside and outside Tibet. In particular, the experience of the exile and the encounter with Indian democracy were important in developing the commitment to human rights and democratic values expressed in the democratic constitution promulgated by the Dalai Lama in 1963. This constitution has also inspired militants in Tibet, particularly the young monks and nuns who demonstrated against Chinese rule in 1987-88. As Ronald Schwartz has shown,30 these young people saw the Dalai Lama’s stance as reflecting a progressive political position because of his articulation of key traditional Buddhist concepts such as compassion, the prohibition of killing, etc. Against Chinese propaganda, these young militants argued that it is the Dalai Lama’s constitution that represents a truly progressive regime, not the Chinese occupation, which was seen as failing to live up to the criteria that it itself had set up.

The use by many Tibetans of religious motives to define themselves as a nation shows the degree to which the analysis of this kind of nationalism as an internalization of Western orientalist discourse misses the mark. When Tibetans represented Tibet to themselves or to outsiders in the early 1960s, they did not lack the discursive means to represent Tibet as “unified, complete and coherent.”31 They did not need and did not use the “the pre- and post-diaspora fantasies of Tibet as a place unlike any other on the globe” – fantasies about which Tibetans knew very little. Rather, they used their own traditional discourse to re-present themselves as belonging to an independent country defined by its Buddhist values, by its relation with Avalokiteśvara, and by its opposition to the Chinese occupation.

Moreover, when Tibetans borrowed Western ideas, as they did increasingly after 1963, they turned to notions like democracy and human rights, not to the disempowering stereotypes that are the hallmark of orientalism. Thus, when the Dalai Lama or the young monks and nuns in Tibet articulated their vision of Tibet, they grounded their views in a mixture of traditional Tibetan Buddhist ideas – such as compassion, karma, and the unique relation between Tibetans and Avalokiteśvara – and Western ideas such as human rights and democratic values. The process that gave rise to this kind of nationalism involves a complex of interactions between Tibetan traditional Buddhist culture, Western, and Indian democratic ideas. Democratic values are pivotal to many contemporary Tibetan nationalists because they are seen as modern incarnations of traditional Buddhist ideals. This is certainly a new way that Tibetans understand their political commitments, a way that is, however, not just an internalization of alien values but an artful synthesis produced out of a complex heterological dialogue in which all the elements involved in the process interact with each other, and in the process change. This is quite different from the claim that the Dalai Lama and the Tibetans who follow him are prisoners of Shangrila.

[21] The reason for this is not to be found in the fact that Tibet was not colonized by the West. The countries that developed some of the most active nationalisms in Asia – Japan and Thailand – never were colonized and yet succeeded in their process of nation building. Similarly, the reason for the failure to develop nationalism is not Buddhism itself. Buddhist countries such as Burma and Sri Lanka, developed their own national self-awareness in different ways. As Melvyn Goldstein has shown, the reasons why Tibet failed to develop in this way have to do with the social structures of Tibetan society, particularly with the dominant role of monasteries and with the imposition of a rigid conservatism over Tibetan society (A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State [[[Wikipedia:Berkeley|Berkeley]]: University of California, 1989]). Also particularly disastrous was the deliberate choice made by the Tibetan ruling elites during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to keep Tibet isolated from what was happening in Asia at that time. This decision prevented Tibet from developing the kind of institutions – such as print capitalism, a well-equipped army, a census, and schools – that could have led to the development of a modern nationalism and to a successful process of nation building. For an argument concerning the link between these institutions and nationalism, see Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism (New York: Verso, 1983).

[22] Georges Dreyfus, “Proto-nationalism in Tibet,” in Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 6th Seminar of the International Association of Tibetan Studies, Fagernes 1992, ed. P. Kvaerne (Oslo: Institute for Comparative Research, 1994) 1: 205-18.

[23] See Ariane Macdonald, “Histoire et Philologie Tibétaines,” in L’annuaire de l’École Practiques des Hautes Études, 4th section (Paris: EPHE, 1968/9); and A. M. Blondeau, “Le Découvreur du Maṇi bKa’-bum: était-il Bon-po?,” in Tibetan and Buddhist Studies Commemorating the 200th Anniversary of the Birth of Alexander Csoma de Kørøs, ed. Louis Ligeti (Budapest: Akademiai Kiado, 1984), 77-123.

[24] E. J. Hobsbawn, Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 46. The use of the term proto-nationalism to describe such a pre-modern sense of collective identity is not without its problems. It can be taken, mistakenly, to imply that modern nationalism is normative, and that traditional senses of collective identity should be seen as prefigurations of this more mature way of understanding communities. The term can also be seen to suggest a kind of continuous existence of a pre-modern sense of collective identity and its transformation into a modern nationalism. Though I am arguing for some degree of continuity between these different senses of identity, I do not accept the idea of a continuous development. I think, however, that it is important to highlight the relevance of more traditional senses of identity to the formation of modern nationalism, particularly in the case of Tibet. This is what my use of the term proto-nationalism is meant to communicate.

[25] Tsering Shakya, The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet since 1947 (London: Pimlico, 1999).

[26] Shakya, The Dragon, 144-47.

[27] Shakya, The Dragon, 165-70.

[28] Tambiah characterizes kingship in East Asia as galactic polity, that is, as a hierarchical structure focused on a symbolic centre. Such a state embraces a diversity of local arrangements organized hierarchically in relation to the centre. See Stanley J. Tambiah, World Conqueror and World Renouncer: A Study of Buddhism and Polity in Thailand against a Historical Background (London: Cambridge University Press, 1976). The horizontal character of nation-states should not, however, be exaggerated. As James Brow remarks, hierarchical elements such as the British identification with the royal family continue to exist in modern states. See James Brow, “Notes on Community, Hegemony, and the Uses of the Past,” Anthropological Quarterly 63, no. 1 (1990): 1-6. Similarly, the unified character of the nation should not be overstated. The unity of nation does not preclude the existence of local allegiances.

[29] P. Christiaan Klieger, Tibetan Nationalism: The Role of Patronage in the Accomplishment of a National Identity (Meerut, India: Archana, 1992), 61-62.

[30] Ronald David Schwartz, Circle of Protest: Political Ritual in the Tibetan Uprising (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994).

[31] Lopez, Prisoners, 200.

Orientalism and Its Impossible Alternatives

This analysis of two aspects of the Dalai Lama’s thought, his Buddhist modernism and his nationalism, illustrates the limitations of a critique of orientalism as applied to Tibetan attempts to articulate their own standpoint. Such limitations are not unique to the study of Tibet, but reflect a larger difficulty with the critique of orientalism in relation to Asian cultures. As an inventory of the orientalist archive, Said’s critique has been enormously valuable. From its inception, however, this critique has found it difficult to speak about Asian cultures in ways that do not reproduce, however involuntarily, the hegemony that it intends to displace.

One of the most noteworthy points regarding Said’s Orientalism is the often referred-to absence of any alternative discourse – that is, of any discourse different from orientalism – both inside and outside of the hegemonic discourse. This absence reflects Said’s tendency to reify orientalism into a seamless process of cultural abstraction that leaves little room for alternatives. Throughout his book, Said relentlessly stresses the continuity of the European tradition in asserting its superiority over Asia. In doing so, he overemphasizes the unity of Western discourse on the Orient, ignoring the heterogeneity of the Western corpus. He thus falls prey to the same essentialism that he criticizes in the West. As James Clifford remarks, “the construction of simplifying essences and distancing dichotomies is clearly not the monopoly of Western Orientalist experts.”32

Said’s picture of orientalism as a constant and mononolithic tradition reflecting Western superiority also ignores the often much more complex realities of history. Said goes so far as to claim an orientalist continuity between Alexander the Great and Jimmy Carter! This claim, as Dennis Porter puts it, “seems to make non-sense of history at the same time as it invokes it with reference to imperial power/ knowledge.”33 This lack of regard for historical realities, which contrasts so markedly with Foucault’s appreciation for historical discontinuities, greatly weakens Said’s project. For, if the Western appropriation of Asia is a monolithic tradition without breaks or alternatives, overturning its hegemony becomes rather difficult.

This is all the more true given that in Orientalism Said grants very little role to any outside alternative. Throughout his book, Said examines the narrative underlying Western domination without ever mentioning any external resistance to the cultural project of domination he examines. Western hegemony unfolds in relation to its own logic, and the people who are being subjugated never appear in any way other than as objects of the colonizer’s power/knowledge. Referring to Said’s book, Aijaz Ahmad rightly remarks:

One of its major complaints is that from Aeshylus onwards the West has never permitted the Orient to represent itself: it has represented the Orient.... But what is remarkable is that with the exception of Said’s own voice, the only voices we encounter in the book are precisely those of the very Western canonicity which, Said complains, has always silenced the Orient. Who is silencing whom, who is refusing to permit a historicized encounter between the voice of the so-called ‘Orientalist’ and the many voices that ‘Orientalism’ is said so utterly to suppress, is a question that is very hard to determine as we read this book. It sometimes appears that one is transfixed by the power of the very voice that one debunks.34

Said’s first reaction was to dismiss these criticisms as irrelevant.35 Orientalism is not intended to provide an overarching theoretical framework, but is a personal inventory of the traces of orientalism.

In a more recent work, Said attempted to answer his numerous critics36 by focusing on the discourse of resistance to imperialism coming from figures such as Fanon, Césaire, Senghor, Tagore, Yeats, etc.37 Said depicts how these intellectuals are attempting to articulate alternatives to the hegemonic discourse of the metropole, often through the adoption of nationalism. Such alternatives, however, are often fraught with danger, for they quickly degenerate into nativism, the reification of national identity, which Said sees as one of the greatest dangers in the postcolonial situation. Few decolonized countries have been able to avoid this danger, and as a result have tended to reproduce colonial pathologies in their own society. There are, however, a few thinkers such as Fanon who offer hope for a discourse of resistance that avoids the murderous essentializations that have marred the history of postcoloniality.

What is remarkable in this later argument is that in tracing the possibility of resistance, Said focuses on canonical writers who write in the language of the metropole, English or French. This focus signals Said’s classicism, his preference for high metropolitan culture over vernacular cultures, which Said goes so far as to describe as less respectable, less worthy of being studied because of “their more obviously worldly affiliation to power and politics.”38 This statement is quite remarkable, for it threatens to undo in one stroke what is perhaps Said’s main point, the stress on the link between high culture and politics. Whatever the truth of this point, Said’s answer shows his difficulty in turning his gaze away from the center toward alternatives. Even when Said intends to focus on alternatives to orientalism, [page 17] he ends up paying attention once more to high culture, and he ignores the more marginal and less canonical forms of discourse, thus threatening to repeat the hegemonic gesture that he has done so much to displace. I believe that this difficulty is not unique to Said but concerns the critique of orientalism as such.

[32] James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature and Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 11. Statements such as “the essence of Orientalism is the ineradicable distinction between Western superiority and Orient inferiority” (Said, Orientalism, 42) and “every European, in what he could say about the Orient, was consequently a racist, an imperialist and almost totally ethnocentric” (Said, Orientalism, 204) reveal Said’s essentialization of Western discourse regarding Asia.

[33] D. Porter, “Orientalism and its Problems,” in The Politics of Theory, ed. F. Barker, et al. (Colchester: University of Essex, 1983), 181.

[34] Aijaz Ahmad, In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures (London: Verso, 1992), 172-73. Author’s emphasis.

[35] Edward Said, “Orientalism Reconsidered,” in Europe and Its Others, vol. 1, ed. Barker, et. al., 17; quoted in B. Moore-Gilbert, Postcolonial Theory (London: Verso, 1997), 51.

[36] The range of these critiques is extremely broad. For a visceral and shrill reaction, see B. Lewis, “The Question of Orientalism,” New York Review of Books, June 24, 1982: 49-56. For more productive critiques see Ahmad, In Theory; Porter, “Orientalism and Its Problems”; Clifford, The Predicament of Culture; and R. Young, White Mythologies: Writing History and the West (London: Routledge, 1990).

[37] Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Knopf, 1993).

[38] Edward Said, “Figures, Configurations, Transfigurations,” Race and Class 32, no. 1 (1990); quoted in Ahmad, In Theory, 216.

Orientalizing or Breaking Down the Barriers?

In assimilating the Dalai Lama’s positions to the orientalist fantasies that he traces so well, Lopez ends up with a similar problem, overlooking the distinctive features of the Dalai Lama’s discourse and reducing it to Western concerns. When he complains that the Dalai Lama’s “proposals appear to blend seamlessly with the pre- and post-diaspora fantasies of Tibet,” Lopez misses the way in which the Dalai Lama’s discourse is embedded into and comes out of its own local Tibetan context. He also fails to consider how the Dalai Lama’s discourse strategically uses and transforms orientalist motifs.

For example, when the Dalai Lama speaks about Tibet as “a place unlike any other on the globe, a zone of peace,” he certainly is using the Western discourse concerning Tibet and the orientalist fantasies that such a discourse has embedded within it. Similarly, the Dalai Lama’s idea of Tibet as “a zone of peace, free of weapons that harm humans and the environment, where the practice of compassion is preserved for the good of the humanity”39 certainly bears the imprint of Western fantasies about Tibet as a special non-worldly place. But this utopianism is not just, however, a reflection of orientalist fantasies, but also the expression of the Buddhist values central to the kind of nationalism advocated by the Dalai Lama and reflected in the Prayer of Truthful Words. Thus, this use of orientalist tropes is not a kind of promiscuous use of highly polluting material threatening some high intellectual project, but it is also an opening of new discursive possibilities. In having recourse to the language of orientalism, the Dalai Lama is using some of its conceptual resources to put forth a new hybrid vision. His idea of Tibet as a special place is an orientalist trope, but it is much more than that; for it is also expresses a modern idea – human rights – as well as a traditional idea, the idea of Tibet as a pure land with a special connection with Avalokiteśvara, an idea that has little to do with Western dreams. The ideas of non-Western figures such as the Dalai Lama often participate simultaneously in several horizons. They are not pure products (if such things ever existed!) but rather hybrid creations that come about in a process of global cultural exchange.

The use here of the concept of hybridity in regard to the Dalai Lama may surprise, for it is usually associated by its leading proponent, Homi Bhabha, with a colonial or postcolonial situation.40 For Bhabha, hybridity marks the degree to which the often mimetic cultural forms developed by the colonized upon contact [page 18] with the colonizers are defenses against the oppression of the dominant order. The situation with the Dalai Lama is obviously quite different, since the dominance he is resisting is not Western but Chinese. Hence, the Dalai Lama is not seeking to formulate a discourse in the language of the oppressor, a language that would destabilize the domination he is resisting, as does Bhabha’s “mimetic man.” Nevertheless, the Dalai Lama’s discourse is hybrid in that it proceeds through the creation of intermediary cultural forms that cannot be understood in terms of a single culture. Understanding such a discourse requires the ability to cross cultural boundaries and to be attentive to the emergence of crossbreed products. It is precisely the recognition of such an ability that I find absent in several of the critics of orientalism.

In analyzing a non-Western hybrid discourse such as that of the Dalai Lama it is also important to remember that a tropological analysis that inventories the Western archives in which these discourses participate is not enough. How the discourse performatively and strategically uses the tropes of orientalism is at least equally relevant. Proceeding in this way, it becomes clear that the Dalai Lama’s discourse does not merely repeat the same old orientalist stereotypes, but rather deploys these for a rather different purpose. It is also important in considering the discourse of such a figure not to focus on a few decontextualized elements, but to place them in their proper historical context. As we saw with Said himself, close attention to history has not always been the strongpoint of the orientalism critique.

The Dalai Lama’s idea of Tibet as a special place is only one of the many ideas that he has articulated during his struggle. In his earlier pronouncements, the Dalai Lama did not use such a trope but emphasized other ideas, such as Tibetan Buddhist heritage and human rights. As I have shown above, these ideas have little to do with Western fantasies about Tibet. They are central themes of Tibetan religious nationalism emerging out of a complex interaction between Tibetan tradition and Western democratic ideas. As such they are not reducible to orientalism and have to be differentiated from the idea of Tibet as a special place.

This later idea appeared in the Dalai Lama’s discourse in a sustained way only during the mid-eighties and it is a mistake to reduce his vision of Tibet to this idea. To do so is to ignore the process through which his religious nationalism developed, and to collapse fifty years of history to a few later events that are then taken to represent the essence of his vision. Far from representing the core of the Dalai Lama’s vision of Tibet, the idea of Tibet as a special place is a late development. It seems to have been part of a choice made by the Dalai Lama and his entourage concerning the best ways to present Tibetan national struggle on the international scene.41 It is in this context that the idea of Tibet as a special place was put forth: as a way to appeal to Western audiences and to break the relative silence that had surrounded the Tibetan cause since the mid-sixties.

The use by the Dalai Lama of the orientalist trope of Tibet as a special place raises several questions. We could ask, for example, was he right to do so? As we know, this strategy was successful on the cultural level, resulting in spectacular popular recognition and culminating with the Dalai Lama’s Nobel Peace Prize. Politically, however, it has yet to yield significant benefits, and the jury is still out. I would argue, however, that this failure to produce tangible political results is due to the international situation, and has little to do with the question of orientalism. But regardless of the truth of this latter point, the fact remains that far from being a prisoner of orientalism, the Dalai Lama was able to use the dominant discourse to further his own rather different agenda. This is essential for our discussion and for understanding orientalism.

The problem with orientalism is not that it misrepresents Asia, creating an ideological distortion that prevents the vision of real Asian cultures. Lopez is quite right when he says that “the search for the real Tibet, beyond representation, lies at the heart of the fantasy of Tibet.”42 This does not mean that all representations of Tibet are equal but that they can have at best a partial claim on truth. A completely accurate depiction of Tibet is an impossible dream. Hence, the problem with orientalism is not that it fails to measure up to this impossible standard, or even that it is a particularly inaccurate representation, but that it marginalizes and thus disempowers the cultures that it constructs as other. This may be true of some of the Western idealizations of Tibet that Lopez examines throughout his book. I believe that the Dalai Lama’s discourse about Tibet as a zone of peace is quite different. As anybody who has seen him speak to a Western audience will recognize, his great strength is his ability to break through cultural barriers and reach a level of commonality with his audience. When the Dalai Lama uses the dominant orientalist discourse and plays into the expectation of his audience, he is not just the prisoner of such language but is also manipulating its resources to break down the barriers that separate him from his audience. Such a strategy emphasizes discursively as well as performatively the breaking down of cultural barriers. As such it is quite different from orientalism and its strategy of marginalizing otherness, regardless of its political success or lack thereof.

Finally, the claim that the Dalai Lama is a victim of orientalism also seems to imply that this discourse is closed, functioning like a prison ensnaring its participants into a maze without escape. This is in fact what I find most surprising in Lopez’s claim that “we are all prisoners of Shangrila,”43 namely, the totalizing suggestion that the discourse of orientalism is closed, trapping us, the alleged prisoners of Shangrila, into a monologue that not even the author is able to break through. But is this really an adequate way to think about language – any language, even the most restrictive and hegemonic language? Is it not the case that the closure attributed to Western orientalism is itself nothing but an impossible dream, a fantasy whose very power depends on its ability to hypnotize us into believing that we can [page 20] speak only with one voice? Are cultures impermeably sealed entities that imprison the people who belong to them, drastically curtailing the exchanges that take place? Or, rather, is it not the case that cultures come to be and to develop through appropriations and interdependencies, borrowing, bringing together, and confounding the many voices that intersect within them?

[39] Lopez, Prisoners, 205.

[40] Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 66-101. For an excellent discussion of the strengths and drawbacks of hybridity, see Moore-Gilbert, Postcolonial Theory, 114-21, 181-203, where the contributions of Wilson Harris and E. K. Brathwaite are considered.

[41] M. McLagan, “Spectacles of Difference: Buddhism, Media Management and Contemporary Tibet Activism,” World Religions and Media Culture 12 (2000), 101-20.

[42] Lopez, Prisoners, 9.

[43] Lopez, Prisoners, 13.

Glossary

Note: The glossary is organized into sections according to the main language of each entry. The first section contains Tibetan words organized in Tibetan alphabetical order. To jump to the entries that begin with a particular Tibetan root letter, click on that letter below. Columns of information for all entries are listed in this order: THL Extended Wylie transliteration of the term, THL Phonetic rendering of the term, the English translation, the Sanskrit equivalent, and the type of term. To view the glossary sorted by any one of these rubrics, click on the corresponding label (such as “Phonetics”) at the top of its column.

Bibliography

Ahmad, Aijaz. In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures. London: Verso, 1992.

Bechert, H. “Buddhist Revival in East and West.” In The World of Buddhism, edited by H. Bechert and R. Gombrich, 272-85. London: Thames and Hudson, 1984.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso, 1983.

Bhabha, Homi. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge, 1994.

Blondeau, A. M. “Le Découvreur du Maṇi bKa’-bum: était-il Bon-po?” In Tibetan and Buddhist Studies Commemorating the 200th Anniversary of the Birth of Alexander Csoma de Kørøs, edited by Louis Ligeti, 77-123. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado, 1984.

Clifford, James. The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature and Art. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988.

Dalai Lama. Freedom in Exile. New York: Harper, 1990.

Dreyfus, Georges. “Proto-nationalism in Tibet.” In Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 6th Seminar of the International Association of Tibetan Studies, Fagernes 1992, edited by P. Kvaerne, 1: 205-18. Oslo: Institute for Comparative Research, 1994.

———. “The Shukden Affair: History and Nature of a Quarrel.” Journal of International Association of Buddhist Studies 21, no. 2 (1999): 227-70.

Goldstein, Melvyn. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. Berkeley: University of California, 1989.

Gyatso, Janet, ed. “Symposium on Donald S. Lopez’s Prisoners of Shangrila.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 69, no. 1 (2001): 163-213.

Hobsbawn, E. J. Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Klieger, P. Christiaan. Tibetan Nationalism: The Role of Patronage in the Accomplishment of a National Identity. Meerut, India: Archana, 1992.

Lewis, B. “The Question of Orientalism.” New York Review of Books, June 24, 1982: 49-56.

[page 21]

Lopez, Donald S., Jr. Curators of the Buddha. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

———. Prisoners of Shangrila: Tibetan Buddhism and the West. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Macdonald, Ariane. “Histoire et Philologie Tibétaines.” L’annuaire de l’École Pratique des Hautes Études. Paris: EPHE, 1969.

McLagan, M. “Spectacles of Difference: Buddhism, Media Management and Contemporary Tibet Activism.” World Religions and Media Culture 12 (2000), 101-20.

Moore-Gilbert, B. Postcolonial Theory. London: Verso, 1997.

Nandy, Ashis. The Intimate Enemy. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Porter, D. “ Orientalism and its Problems.” In The Politics of Theory: Proceedings of the Essex Conference on the Sociology of Literature, July 1982, edited by F. Barker, et al., 179-93. Colchester: University of Essex, 1983.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Vintage, 1979.

———. “Figures, Configurations, Transfigurations.” Race and Class 32, no. 1 (1990): 1-16.

———. “Orientalism Reconsidered.” In Europe and Its Others, vol. 1, edited by F. Barker, et al., 14-27. Colchester: University of Essex, 1985.

———. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Knopf, 1993.

Schwartz, Ronald David. Circle of Protest: Political Ritual in the Tibetan Uprising. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Shakya, Tsering. The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet since 1947. London: Pimlico, 1999.

Tambiah, Stanley J. World Conqueror and World Renouncer: A Study of Buddhism and Polity in Thailand against a Historical Background. London: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary. Springfield: Merriam-Webster, 1986.

Young, R. White Mythologies: Writing History and the West. London: Routledge, 1990.

Read more: http://www.thlib.org/collections/texts/jiats/#!jiats=/01/dreyfus/c2/#ixzz2Rp3ynKtJ

Notes

[1] Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary (Springfield: Merriam-Webster, 1986), 832. See also Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Vintage, 1979), 51, 73.

[2] Donald S. Lopez, Jr., Curators of the Buddha (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

[3] Donald S. Lopez, Jr., Prisoners of Shangrila: Tibetan Buddhism and the West (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

[4] See, for example, the symposium on Donald S. Lopez’s Prisoners of Shangrila in Journal of the American Academy of Religion 69, no. 1 (2001): 163-213.

[5] For Said, the Orient as studied by Orientalists is not just some part of the world “out there,” waiting to be discovered and studied. Rather, it is a cultural construction constituted by certain discourses, orientalism, that separate the West from Asia by focusing on the latter’s odd and unusual traits, customs, and habits. In this way, the Orient is constructed – or to use Said’s formulation, the Orient is “orientalized” – as the object to be represented and controlled by the West, the foil against which the West can identify itself as different and intrinsically superior (Said, Orientalism, 5).

[6] Lopez, Prisoners, 10.

[7] Lopez, Prisoners, 13.

[8] Lopez, Prisoners, 13.

[9] This brief account follows Lopez’s summary (Prisoners, 185) as well as H. Bechert, “Buddhist Revival in East and West,” in The World of Buddhism, eds. H. Bechert and R. Gombrich (London: Thames and Hudson, 1984), 275-76.

[10] Lopez, Prisoners, 185.

[11] Lopez, Prisoners, 196.

[12] Lopez, Prisoners, 200.

[13] Lopez, Prisoners, 200.

[14] Lopez, Prisoners, 205.

[15] Lopez, Prisoners, 206.

[16] Georges Dreyfus, “The Shukden Affair: History and Nature of a Quarrel,” Journal of International Association of Buddhist Studies 21, no. 2 (1999): 227-70.

[17] The Dalai Lama, Freedom in Exile (New York: Harper, 1990), 25.

[18] Ashis Nandy, The Intimate Enemy (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983).

[19] The Dalai Lama, Freedom in Exile, 31. My brackets.

[20] For more details on this episode, see Dreyfus, “The Shukden Affair.”

[21] The reason for this is not to be found in the fact that Tibet was not colonized by the West. The countries that developed some of the most active nationalisms in Asia – Japan and Thailand – never were colonized and yet succeeded in their process of nation building. Similarly, the reason for the failure to develop nationalism is not Buddhism itself. Buddhist countries such as Burma and Sri Lanka, developed their own national self-awareness in different ways. As Melvyn Goldstein has shown, the reasons why Tibet failed to develop in this way have to do with the social structures of Tibetan society, particularly with the dominant role of monasteries and with the imposition of a rigid conservatism over Tibetan society (A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State [[[Wikipedia:Berkeley|Berkeley]]: University of California, 1989]). Also particularly disastrous was the deliberate choice made by the Tibetan ruling elites during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to keep Tibet isolated from what was happening in Asia at that time. This decision prevented Tibet from developing the kind of institutions – such as print capitalism, a well-equipped army, a census, and schools – that could have led to the development of a modern nationalism and to a successful process of nation building. For an argument concerning the link between these institutions and nationalism, see Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism (New York: Verso, 1983).

[22] Georges Dreyfus, “Proto-nationalism in Tibet,” in Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 6th Seminar of the International Association of Tibetan Studies, Fagernes 1992, ed. P. Kvaerne (Oslo: Institute for Comparative Research, 1994) 1: 205-18.

[23] See Ariane Macdonald, “Histoire et Philologie Tibétaines,” in L’annuaire de l’École Practiques des Hautes Études, 4th section (Paris: EPHE, 1968/9); and A. M. Blondeau, “Le Découvreur du Maṇi bKa’-bum: était-il Bon-po?,” in Tibetan and Buddhist Studies Commemorating the 200th Anniversary of the Birth of Alexander Csoma de Kørøs, ed. Louis Ligeti (Budapest: Akademiai Kiado, 1984), 77-123.

[24] E. J. Hobsbawn, Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 46. The use of the term proto-nationalism to describe such a pre-modern sense of collective identity is not without its problems. It can be taken, mistakenly, to imply that modern nationalism is normative, and that traditional senses of collective identity should be seen as prefigurations of this more mature way of understanding communities. The term can also be seen to suggest a kind of continuous existence of a pre-modern sense of collective identity and its transformation into a modern nationalism. Though I am arguing for some degree of continuity between these different senses of identity, I do not accept the idea of a continuous development. I think, however, that it is important to highlight the relevance of more traditional senses of identity to the formation of modern nationalism, particularly in the case of Tibet. This is what my use of the term proto-nationalism is meant to communicate.

[25] Tsering Shakya, The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet since 1947 (London: Pimlico, 1999).

[26] Shakya, The Dragon, 144-47.

[27] Shakya, The Dragon, 165-70.

[28] Tambiah characterizes kingship in East Asia as galactic polity, that is, as a hierarchical structure focused on a symbolic centre. Such a state embraces a diversity of local arrangements organized hierarchically in relation to the centre. See Stanley J. Tambiah, World Conqueror and World Renouncer: A Study of Buddhism and Polity in Thailand against a Historical Background (London: Cambridge University Press, 1976). The horizontal character of nation-states should not, however, be exaggerated. As James Brow remarks, hierarchical elements such as the British identification with the royal family continue to exist in modern states. See James Brow, “Notes on Community, Hegemony, and the Uses of the Past,” Anthropological Quarterly 63, no. 1 (1990): 1-6. Similarly, the unified character of the nation should not be overstated. The unity of nation does not preclude the existence of local allegiances.

[29] P. Christiaan Klieger, Tibetan Nationalism: The Role of Patronage in the Accomplishment of a National Identity (Meerut, India: Archana, 1992), 61-62.

[30] Ronald David Schwartz, Circle of Protest: Political Ritual in the Tibetan Uprising (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994).

[31] Lopez, Prisoners, 200.

[32] James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature and Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988), 11. Statements such as “the essence of Orientalism is the ineradicable distinction between Western superiority and Orient inferiority” (Said, Orientalism, 42) and “every European, in what he could say about the Orient, was consequently a racist, an imperialist and almost totally ethnocentric” (Said, Orientalism, 204) reveal Said’s essentialization of Western discourse regarding Asia.

[33] D. Porter, “Orientalism and its Problems,” in The Politics of Theory, ed. F. Barker, et al. (Colchester: University of Essex, 1983), 181.

[34] Aijaz Ahmad, In Theory: Classes, Nations, Literatures (London: Verso, 1992), 172-73. Author’s emphasis.

[35] Edward Said, “Orientalism Reconsidered,” in Europe and Its Others, vol. 1, ed. Barker, et. al., 17; quoted in B. Moore-Gilbert, Postcolonial Theory (London: Verso, 1997), 51.

[36] The range of these critiques is extremely broad. For a visceral and shrill reaction, see B. Lewis, “The Question of Orientalism,” New York Review of Books, June 24, 1982: 49-56. For more productive critiques see Ahmad, In Theory; Porter, “Orientalism and Its Problems”; Clifford, The Predicament of Culture; and R. Young, White Mythologies: Writing History and the West (London: Routledge, 1990).

[37] Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Knopf, 1993).

[38] Edward Said, “Figures, Configurations, Transfigurations,” Race and Class 32, no. 1 (1990); quoted in Ahmad, In Theory, 216.

[39] Lopez, Prisoners, 205.

[40] Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 66-101. For an excellent discussion of the strengths and drawbacks of hybridity, see Moore-Gilbert, Postcolonial Theory, 114-21, 181-203, where the contributions of Wilson Harris and E. K. Brathwaite are considered.

[41] M. McLagan, “Spectacles of Difference: Buddhism, Media Management and Contemporary Tibet Activism,” World Religions and Media Culture 12 (2000), 101-20.

[42] Lopez, Prisoners, 9.

[43] Lopez, Prisoners, 13.