The buddhist conception of omniscience

McMaster University

Lakshuman Pandey, M.A. (Banaras Hindu University) Shastri (Sanskrit University)

M.A. (MG~aster University)

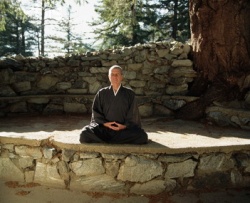

Professor T.R.V. Murti

As its central purpose, the thesis outlines the Buddhist conception of human omniscience as developed by the philosophers of later Vijnanavada Buddhism, i.e., DharmakIrti, Prajnakaragupta ;- ,-

Santaraksita and Kamalasila. It attempts to show how those philosophers dialectically established the possibility of human omniscience and the omniscience of the Buddha.

The concept of human omniscience was introduced into Indian philosophy because of the religious controversies between Heterodox (Nastika) schools, such as Jainism and Buddhism, and Orthodox (Astika) schools, - , -- - -~ - - especially Nyaya-Vaise~ika, Sankhya-Yoga, Mimamsa and Vedanta. The Mlma~sakas began the argument with claims for the omniscience of the Vedas; the Naiyayikas followed with the attribution of omniscience to God. When the Buddhists, in turn, maintained the omniscience of the Buddha, the Mlma~sakas raised objections to the concept of human omniscience, the omniscience of the Buddha, of God, and of any human religious teacher.

In order to refute these objections and to assert once again the superiority of the Buddha and his teachings of Dharma, the later Buddhist philosophers sought to dialectically established the concept of human omniscience. The Buddhist argument was the product of constant interaction and debate with other Indian religious and philosophical schools, and it is clear that omniscience was and continues to be one of the pivotal topics for all schools of Indian philosophy. The Buddhists have used logical arguments to support the concept of human omniscience. They have established the omniscience of the Buddha using the logical methods of presumption and inference.

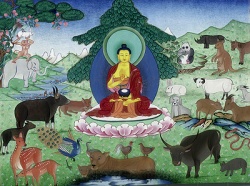

They have provided the answers . from the Buddhist point of view to the MImamsakas' objections against the concepts of human omniscience and the omniscience of the Buddha. The Buddhists maintain that an omniscient person perceives all objects of the world simultaneously in a single cognitive moment. They have also argued that only an omniscient person can teach Dharma. The aim of the Buddhists was to prove the superiority of Buddhism among all religions, because it is based on the teachings of an omniscient being. In brief, this thesis outlines the development of the concept of omniscience, which the Buddhists hold to be the necessary and sufficient condition for perception of supersensuous truths such as Dhatma. iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is with a very special sense of gratitude that the author acknowledges his Gur~ (teacher), Dr. T. R. V. Murti. To him alone is rendered sincere and differential gratitude for the kind encouragement t inspiration, direction, and supervision which led to the successful completion of this thesis. Professor Murti has been outstandingly generous, sympathetic and unfailing in his understanding of the time and effort which this research demanded. Every page and every line of this thesis represents the author's appreciation and gratitude for his Guru. The impact of his excellent guidance is felt everywhere but perhaps most of all in the area of personal fulfillment, for which the author is forever in his debt. Very sincere gratitude and appreciation are also expressed to Professor J. G. Arapura, Professor S. K. Sivaraman, Professor G. P. Grant, Professor Paul Younger, Professor L. I. Greenspan, Professor S. Ajzenstat, Professor A. E. Combs, Professor E. B. Heaven, and Professor P. C. Craigie.

The author would also like to offer his very sincere thanks and gratitude to Dr. E. P. Sanders, who was so generous with his time and advice.

Thanks are extended to McMaster University for awarding Graduate Teaching Fellowships which enabled the author to carryon his research.

A word of thanks to Mrs. Susan Phillips for her kind help in typing this thesis.

The substance of this dissertation consists of an examination in greater depth and more extensive scope of a topic which was examined in a preliminary way in the writer's M.A. thesis, The Buddha as an Omniscient Religious Teacher; that thesis was submitted to the Department of Religion, McMaster University, and accepted in 1969. TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

In broad terms the purpose of this thesis is to present the logical proofs given in support of the omniscience (Sarvajnata) of the

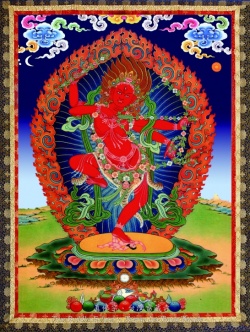

- - Buddha by the later Buddhist philosophers: Dharmakirti, Prajnakaragupta Santaraksita and Kamalasila. These philosophers lived after the fifth century A.D. and their writings represent the last phase of Indian Vifnanavada Buddhism.

In Indian philosophy, logical argument was a commonly accepted method used to defend a religio-philosophical concept already accepted at the time. With this intention, the above named exponents of Buddhism have set forth logical evidence in order to establish the fact "that only the Buddha was an omniscient (Sarvajfia) religious teacher". Undoubtedly religious practices implying omniscience precede their actual conceptualization: but the concern here is not with the realization of omniscience, but with its rationalization. The main concern of this thesis will be to show that the Vijnanavadi Buddhist philosophers offer arguments that successfully answer the objections urged by the Mfmamsakas against the conception of human omniscience. In addition, we will also try to show that these Buddhist philosophers offer further arguments which establish the complete validity of this fundamental Buddhist tenet. Here they are not only philosophers or logicians but they are theologians defending the Buddhist tenets. In fact, the concept of omniscience is not only a philosophical and religious problem but also a theological problem. 1

The aim of these Buddhist philosophers is to prove the superiority of Buddhism among all religions, because it is based on the teachings of an omniscient teacher, that is, the Buddha, who is the only omniscient religious teacher according to them. By dialectical establishment of human omniscience and omniscience of the Buddha, these authors prove the authority and infa-libility of the Buddha and his teachings or Dharma. The Sanskrit word Sarvajna (Sarva meaning lI a1 1 11 and jua meaning "knower") is translated by the English as "omri.s ci ent " or "all-knowing" person. Here "Sarva" means all the existing things of the past, present and future. Thus, one who knows all the things of the universe either successively or simultaneously is called omniscient (SarvaJna). The Sanskrit words Sarvajna, Sarvasarvajna, Sarvakarajna, Sarv~karagrahi, ~~rvavit, Sarvasarvavit, Sarvavedl, Visvavedas, Visvavidvan, Visvacaksu, Visvadrasta are used as synonyms, meaning a person who knows everything. According to Paniniya Sanskrit grammar, he who knows everything is omn.lS.Clent (S arva.J~na) . 1 The Pali word Sabbannu and the Prakrta word

- - Kevalin are used for the omniscient person. In both Pali and Prakrta grammar, the meaning of the words Sabbannu and Kevalin, respectively, is similar to that of Paniniya Sanskrit grammar. The Sanskrit word Sarvajnata, the Pali word Sabbannuta-nana and the Prakrta word Kevala (Omniscience) mean to have the knowledge of each and every thing in the universe. However, the words Sarvajnata, Sabbannuta-nana and Kevala are translated into English by the word \arvam janatiti sarvajnah, ato'nupasarge kah , astadhyayi 3,2,3. 3

"oumt.scf.ence" or "all embracing knowledge". The concept of omniscience (sarvajnata) can be conceived from two points of view. From the objective point of view, "omrri.acLence" means knowing everything numerically and quantitatively. From the qualitative point of view, the word "omniscience" means to have the knowledge of the epitome of everything. This type of knowledge reveals two kinds of meaning: first, knowledge of Reality (tattvaJnata) and second, knowledge of Dharma (dharmajnata) In Indian philosophy the word Sarvajna has been nsed in a special sense to mean a person possessing the knowledge of supersensuous truths such as Dharma, heaven (svarga) and liberation (moksa), apart from the knowledge of the sensuous objects of the world. In other words, the omniscient person is the knower of reality (t at tvajfia) ,

To establish its o,vn authority, each school of Indian philosophy has developed a different concept of omniscience, and has used this word with a slightly different connotation. The School of Carvaka does not hold the possibility of omniscience. The School of Mimamsa maintains that the Vedas are omniscient, but that no being can be omniscient. The School of Nyayavai~esika Se£vara-Samkhya and Yoga maintain the omniscience of God. The School of Advaita Vedanta holds the omniscience of God as well as the omniscience of man. Although they do not believe the authority of the Vedas, or of God, or Prakrti, the Buddhists and Jainas hold that only a human being can become omniscient. The Buddhists hold that omniscience (sarvajnata) depends upon the full knowledge of all things, sensuous and supersensuous. According to the Buddhists, this follows from the removw_ of the hindrance of 4

affliction (kle§avarana) and hindrance of cognisable things (j"neyavarana). The Buddhists hold that that person alone is omniscient who knows the whole world in its real form of "soullessness" (anatmavada). They further assert that only the Buddha, not the other teachers, fulfills all the conditions of this definition. Therefore, he has been placed above all other religious teachers by the Buddhists. It seems that the concept of omniscience arose in Indian thought because of the desire to describe supersensuous realities such as Dharma, God, the self, heaven and liberation, etc. These supersensuous realities are commonly accepted by Indian religious traditions. They cannot be verified, however, by normal human perceptions. Consequently, the question arises as to whether anybody can have a direct vision of Dharma and other supersensuous truths. The limit of human knowledge arouses a desire to have an unlimited knowledge. Is this possible? This recurring problem in Indian metaphysical thinking has drawn the attention of Indian thinkers to the concept of Omniscience. Every understanding of religious authority is associated in some way with the concept of Omniscience and this has become a major matter of discussion in Indian philosophy.

It is the unique characteristic of Indian philosophy that it lays so much emphasis on the nature and limitation of knowledge. When all the limitations of knowledge are removed, the state of omniscience is achieved. In other words, omniscience is the culmination of knowledge. Indian thought generally takes the position that the limitations of knowledge can be removed and that one can acquire the knowledge of supersensuous realities. lihen the veil covering the knowledge is removed, 5

the knowledge of each and every thing of the universe can shine forth in the person's intellect. The intellect can reflect these objects like a mirror. This knowing in its most perfect form is called omniscience. Although every system of Indian philosophy deals with the concept of omniscience, Buddhism, Jainism and Mimamsa have dealt with it in greater detail.

In Indian thought Dharma is derived from two sources: first, the divine sources (like gods, God and the Vedas); second, human sources (like the Buddha and Mahavira). Divine sources are already attributed the concept of Omniscience. That is to say, all-knowingness is the very nature of divinity. Consequently, the Dharma can be revealed through divine sources. But, here the question arises whether the Dharma can be revealed by a human being. This is possible if a human being can become Omniscient. Although at first glance one might feel that this was an untenable position, Indian philosophy does not take that attitude since it refuses to accept that there is ultimately a distinction between man's most basic nature and divinity itself. Indian thought accepts the possibility of enlightenment by means of spiritual discipline (yoga). This enlightenment is the self-realization of the divIne character of man. A person who becomes enlightened also removes the hindrance which lies in the way of the acquisition of knowledge. Thus every enlightened person necessarily becomes omniscient. The enlightened person is fully entitled to reveal Dharma because Omniscience involves a revelation of Dharma.

Now the question is whether a supersensuous reality, like Dharma, can be directly perceived or not. The Carvaka and Mfmamsa hold 6

that Dharma cannot be perceived by any being. They do not believe in any omniscient being or a knower of Dharma. All other systems of Indiml philosophy believe in the direct intuitive realization of Dharma. They believe in the exist.ence of omniscient beings, either divine or human, as the perceivers of Dharma. Invariably every religious teacher has been declared the knower of highest truth or the secrets of Dharma because of his omniscience.

It is hard to trace when this concept; of omniscience appeared as a conscious religio-philosophical problem in Indian thought. It is also hard to say whether human omniscience came first, because every enlightened person was considered to be omniscient, or whether divine omniscience came first, because some gods of the Veda~ were attributed with omniscience, or whether God himself was conceived to be omniscient by the school of Nyaya Vai~e?ika, Se§vara- Sankhya, Yoga and Vedanta. It is evident from the Vedas that Indian thought has accepted the concept of human omniscience since the very beginning. Because the concept of human omniscience is prominent or popular from the very beginning of Indian thought, one might get the idea that human omniscience was introduced to Indiffil thought first and later on this idea gave rise to divine omniscience and gradually God, gods, and the Vedas were all accepted as omniscient. This view would seem to be supported by the Vedas themselves because the concept of human omniscience can be found there in that the Rsis (or seers) of the Vedas are thought of as omniscient.

Sankya Yoga, Nyaya. Vai.Ise.sika, Jainism and Buddhism each claim that their system was founded by an omniscient person. However, we do not agree with the view that human omniscience arose first in 7

Indian thought. We put the Vedas prior to any philosophical system of India. In the Vedas, the gods are thought of as omniscient and they in turn have the capacity to make people omniscient R..sis. Therefore we conclude that the concept of divine omniscience was developed first in Indian thought and it gradually gave rise to the concept of human omniscience.

Was the concept of human omniscience developed because of its attribution to God or the Vedas, or was the concept attributed to God or the Vedas because an enlightened person was thought to be omniscient? Or was this concept attributed to God, the Vedas and man simultaneously? These questions do not pertain particularly to the subject of this thesis.

It seems that this concept of human omniscience was first introduced into Indian thought as a philosophical concept because of the religious controversies among Heterodox (Nastika) Schools, specifically Jainism and Buddhism, and Orthodox (Astika) Schools, specifically

- I - - -- - --- Nyaya-Vaisesika, Sarikhya-Yoga , Purva-Hlrnafos a and Ut.t aram.lmarhs a , The religious teachers of some of the Nastika schools were claimed omniscient for themselves in order to prove the validity of their teachings. The Astika Schools had already accepted the omniscient authority of some supersensuous and super-human realities like God or the Vedas as proof of the validity of their religious teachings. But those who were not the followers of this tradition had to prove their o,vn religious authority by attributing omniscience to their religious teachers. Thus the concept of human omniscience came into philosophy as a reaction against the concept of divine omniscience attributed to the gods, God 8

or the Vedas.

In the period following the sixth century B.C. (that is, the time of the Buddha and Mahavira) there was a greal deal of discussion among Indian philosophers on the concept of human omniscience. Because the Buddha and Mahavira were considered to be omniscient teachers by their respective followers, a discussion ar08~ as to whether or not a person can be omniscient. As a result of this discussion, two main streams of thought have emerged concerning human omniscience. According to one position, that is, the Caravaka and Mimamsa, an omniscient person is an impossibility; to the other, that is, the school of the Nyaya-Vaiesika, Sankhya-Yoga, Advaita Vedanta, Buddhism and Jainism, omniscience can be achieved by a human being. From the time of the Buddha and onward, the concept of omniscience began to be used in Indian religious and philosophical systems in order to establish the omniscient authority of the Dharma. Whether or not this religious authority was a person or the Vedas or God, it was essential that the authority be considered omniscient. It was felt that only in this way was it possible to have the true Dharma, because an omniscient authority knows the true nature of everything, sensuous and supersensuous. Only the true Dharma, if followed properly, can fulfill the real purpose of life by leading the people to prosperity in this life and to the highest good or liberation after life. Thus the concept of omniscience was accepted as an essential part of the religio-philosophical discussions in the history of Indian thought, and every religious teacher or authority was necessarily considered to be omniscient.

9

Although the concept of omniscience was propounded in the sixth century B.C., it did not become prominent as a subject of philosophical debate and controversy until the second century A.D. The catalysts for this controversy were the numerous speculations on the true nature of Dharma by every school of Indian philosophy. They all agreed that the true nature of Dharma should be revealed by an omniscient authority. So the controversy over Dharma, its real nature, its revealer or teacher, led to the co-relative controversy over omniscience in the second century at the time of Jaimini the Mimamsaka. He was prompted to inquire into the true nature of Dharma, against Vadarayana the Uttaramimamsaka who desired to know the true nature of Brahman. This led naturally to the desire to define the true nature of omniscience. The concept of omniscience became a burning problem in Indian thought in the seventh century mainly because of the controversy regarding the concept of Dharma among Mimamsa, Jainism and Buddhist schools. The school of Mimamsa did not accept the possibility of omniscience in any human being and rejected this concept through various modes of argument. To refute the arguments of Mimamsa and to establish the concept of omniscience in general, and omniscience in particular (that is, human omniscience), the heterodox schools of Jainism and Buddhism dialectically established the concept of human omniscience. This concept of omniscience became very popular in religious and philosophical discussions of Indian thought; when Kwnarila tried to refute this concept of omniscience in any being and established the fact that Dharma can be known only through the omniscient Vedas, this concept became a matter for dispute among the other systems of Indian 10

thought. The Jains and the Buddhists became the main opponents of Mfmamsa on this issue and argued for the possibility of human omniscience. In fact they refuted the possibility of divine omniscience by rejecting the omniscience of gods, God, and the Vedas, but they did establish the concept of human omniscience. They emphasized th~t Qn1y a human being can be omniscient. They did this because they wanted to prove the validity and superiority of their own religion by proving that their religion was founded by an omniscient religious teacher. The omniscient knows the true nature of everything, sensuous or supersensuous. Therefore he cannot misguide people while teaching supersensuous realities like Dharma, heaven, hell, soul, rebirth, liberation, etc.

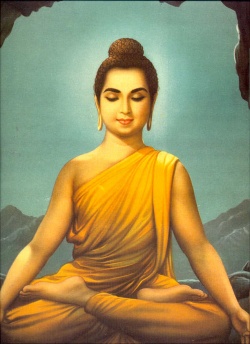

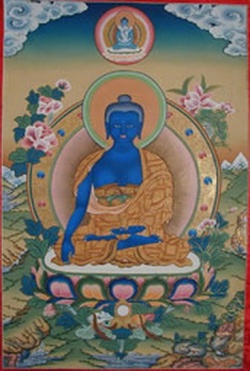

Early Buddhism does not lay emphasis on the omniscience of Buddha, yet still it asserts him as the knower of Dharma. However, the Mahayana Buddhist regards Buddha as the omniscient one and because of his all-knowingness he has been declared as the authority of Dharma. In the earliest Pali Nikayas the Buddha has not explicitly declared himself as the omniscient religious teacher nor has he been regarded by his disciples as an all-knowing religious teacher. In fact, Buddha did not like to involve himself in metaphysical discussions because his aim was confined to revealing the Dharma. He kept himself aloof from answering the fourteen unspeakable questions (avyakrta-pra~na). In the seventh century, A. D. Kumarila rejected the idea of a being (human or divine) as the knower of Dharma and tried to establish the authority of the Vedas for knowing Dharma. After that time it became essential for the Buddhist philosophers to counter the arguments of 11

Kumarila in order to establish the authority of the Buddha as a religious teacher. Dharmakfrti holds that Dharma can be perceived by a being directly, therefore a being can be the knower of the Dharma. Thus, by various modes of argument, he has established the authority of the Buddha as the only authoritative religious teacher in order to put Buddhism on at least an equal footing with other religious systems of India.

The omniscience of the Buddha is emphasized and elaborated mainly .<;>/- - by the Vijnanavad Buddhist philosophers, beginning about the fifth century A.D. The fifth century A.D. was the beginning of the golden period of Indian philosophy. Here we find a tripartite struggle between the Mfmarnsa, Nyaya and Buddhist schools. This tripartite struggle was originally started by Dinnaga, the father of medieval logic in India. He criticized the Nyaya-Sutra of Ak,sapada Gautama and its co~nentary Dignaga by the celebrity he won in disputations has been one of the most powerful propagators of Buddhism. He is credited with having achieved the "conquest of the wo r l.d , "* Just as a universal monarch brings under his sway all India, so is the successful winner of disputations the propagator of his creed over the whole of the continent of India. Cashmere seems to have been the only part of India where he has not been, but he was visited by representatives of that country who later on founded schools there. These schools carried on the study of his works and produced several celebrated logicians. 2 Dinnaga felt that the charges levelled by the school of ~timamsa and Nyaya against the Buddhist doctrines could not be disproved 2Th• Stcherbatsky, Buddhist Logic, Vol. I, "Introduction", p. 34. *Footnote No. I in original source. dig-vijaya. 12

without accepting a new form of logic. This new logic would enable Buddhism to be on an equal footing theologically, philosophically and religiously with the other Indian traditions. This was most essential since Buddhism until this time was devoid of an adequate framework in which to interpret the tradition of the Buddha. Dinnaga, however, gave a new definition of logic on the basis of Buddhist philosophy and from this standpoint he criticized the views of others and set forth a new logical proof of Buddhist doctrines: The Buddhist philosopher Dinnaga (c. 425 A.D.) may be regarded as the founder of the school of pure logic in Buddhism•.•. It is interesting to note that in the

hands of Dinnaga, Nyaya becomes a pure

science of 10gic.•.. With Dinnaga, as with other logicia~s of the Medieval School, the utility of Nyaya primarily lay in its being a means of defence and attack in the philosophical controversies that were then raging

in the country. He tries his best to demolish the position of Vatsyayana, the commentator of the Nyaya-sutras. Udzotakara (c. 550 A.D.) came forward to defend Vatsyayana against Dinnaga.

The task of defending Dinnaga against

Udyotakara was undertaken by DharmakIrti, (c. 600 A.D.) pupil's pupil of Dinnaga .••. DharmakIrti also criticizes the views of Dhartrhari and Kumarila as well. DharmakIrti in his turn is criticized by Vyomasiva, Akalanka, Haribhadra and Hayanta. 3

Eventually the Jaina, Sankhya-Yoga, MImamsa and Nyaya Schools also adopted their own logical methods to support their doctrines and criticize those of others. Uddyotakara, a propagator of the Nyaya 3A. S. Altekar, Introduction to the Pramanavartikabhashyam (ed. by Rahula Sankrtyayana, Banaras, 1953), pp. 6-7. 13

School, in his book Nyaya-Vartika, has tried to refute the arguments of Dinnaga against the Nyaya doctrines. God, he holds, is the basis of Dharma because He is the only omniscient supreme being. He has proved the sale omniscience of God on the basis of His function as creator of the whole universe. Only a being who is the creator of the universe can be omniscient. It is) therefore, impossible for any human being like the Buddha or Vardhamana Mahavfra to be the omniscient religious teacher.

To answer the objections of Uddyotakara, the Naiyayika and the Mfmamsakas and to re-establish the Buddhist doctrines, Dharmakfrti wrote the Pramana-Vartika. His criticism was answered by Vacaspati Misra in his book Nyaya-Vartike-Tatparya-Tfka. Dharmakirti also criticized vigorously the doctrine of the Mimarnsakas. His criticism

- I - was answered by Kumarila in his book Slokavartika. In order to reestablish the doctrine of Mfmamsa he severely attacked the Buddhist doctrines and attempted to prove the authority of the Vedas. He holds that only the Vedas can be omniscient and an omniscient being, whether a human being or a god, is an impossibility. According to him, the non-omniscient teachers like the Buddha or Vardhamana should not be accepted as authority for Dharma.

Thus the schools of Mfmamsa and Nyaya challenged the religious authority of Buddhism by seeking to disprove the omniscience of any human being. On this basis the Buddha's teachings regarding Dharma were not accepted as authoritative by them and were seen as misleading. The attack of Kumarila, Uddyotakara and Vacaspati Misra on the doctrines of Buddhism, and their refutation of the omniscience of the Buddha, 14

shook the position of Buddhism as a religion and it became difficult for people to have faith in the teachings of the Buddha . ... Buddhism in India was doomed. The most talented propagandist could not change the run of history. The time of Kumarila and Sankara-acarya, the great champions of brahmanical revival and opponents of Buddhism, was approaching .... What might have been the deeper causes of the decline of Buddhism in India proper and its survival in the border lands, we never perhaps will sufficiently know, but historians are unanimous in tel!ing us that Buddhism at the time of Dharmakirti was not on the ascendency, it was not flourishing in the same degree as at the time of the brothers Asanga and Vasubandhu. The popular masses begffil to return their face from that philosophic, critical and pessimistic religion, and reverted to the worship of the great brahmin gods ...•

Dharmakfrti seems to have had a foreboding of the ill fate of his religion in India. He was also grieved by the absence of pupils who could fully understand his system and to whom the continuation of his work could have been entrusted.

Just as Dignaga had no famous pupil, but his continuator emerged a generation later, so was it that Dharmakirti's real continuator emerged a generation later. 4

The Buddhist philosophers of the age felt the need to answer this challenge by establishing the Buddha as the only omniscient religious teacher in order to prove that Buddhism was as valid as the Vedic tradition, if not superior. They have tried to prove that only a human being could be OlIDliscient, not the Vedas or God. They also tried to demonstrate that among human beings who have been acclaimed as omniscient religious teachers only the Buddha is omniscient because his teachings have not been disproved by any valid means of cognition. 4TIl. Stcherbatsky, op. cit., p. 35.

15

They have used logical arguments to support the omniscience of the Buddha so that they could prove that Buddhism was the only true Dharma, since only Buddhism has been taught by an omniscient religious teacher. Dinnaga paved the way for development of the Buddhist proofs for the omniscience of the Buddha by providing the logical structure.

- r-:»: --

The later Sautrantika ViJnanavadi Buddhists adopted this dialectical method in discussing the omniscience of the Buddha. We should, however, remember that the logicians of the age had cultivated a purely rational outlook to a great extent. Dinnaga was no doubt held in high esteem by the Buddhists but this did not prevent Dharmakirti, his vartikakara, from dissenting fr~m him and maintaining that the example, or Udaharana, cannot form part of syllogism. The very emergence of vartika as a form of literature is a clear proof that rationalism was fairly well developed in the period; the vartikakaras wer e no doubt conunenting upon earlier works .... 5

Dharmakirti, however, has not rested his case on the omniscience of the Buddha, because he felt that the omniscience of any person cannot be examined by any empirical criterion. But he maintains that the Buddha is a reliable guide to Dharma, because he possesses true know- <V- - 6

ledge (jnanavan).

This is much more so because the whole chapter on the validity of knowledge is supposed to contain only a comment upon the initial stanza of Dignaga's work. This stanza contains a salutation to Buddha who along with the usual titles is here given the title of "Embodied Log!c~ (pramana-bh~ta).* The whole of

Mahayanistic Buddho1ogy, all the proofs of 5

A. S. Altekar, ~. cit., p , 7.

6 - - Prama~a-Vartika (edited by Rahul Saw<rityayana, Patna, 1938), II, pp. 145-146.

16

the existence of an absolute, Omniscient Being are discussed under that head.

We would naturally expect the work to begin with this chapter upon the validity of knowledge and the existence of an Omniscient Being .•.•A further notable fact is that the chapter on Buddhology, the religious part, is not only dropped in all the other treaties, but

Dharmakirti most emphatically and clearly expresses his opinion to the effect that the

absolute omniscient Buddha is a metaphysical entity, something beyond time, space and experience, and that therefore, our logical knowledge being limited to experience, we can neither think nor speak out anything definite about him,** we can neither assert nor deny his existence. 7

The omniscience of the Buddha was most convincingly demonstrated '-'- - in the last phase of Indian Vijnanavada Buddhism. Th. Stcherbatsky names it "The Third or Religious School of Commentators".8 The philosophers of this school have followed the logical tradition of Dinnaga and Dharmakirti in proving the validity of knowledge. In this connection they have logically established the concept of human omniscience as well as the omniscience of the Buddha. Prajtiakaragupta in Pramanavartika-Bhasyam (or Vartikalankarah), 1- 1 Santaraksita in his Tattvasangraha and Kamalasila in his Panjika have gone further than Dinnaga and Dharmakirti and have dialectically established the concept of human omniscience and the omniscience of the 7Th• Stcherbatsky, EE-' cit.,

while answering the objections of Vacaspatimisra and Kumarila. These Buddhist philosophers have accepted the possibility of human onmiscience and have maintained through various modes of logical argument that only the Buddha and no other religious teacher is omniscient, because his teachings of Dharma have not been disproved by the accepted valid means of cognition (pramana). By holding the concept of human omniscience and the omniscience of the Buddha, the Buddhists do not mean that the omniscient person should know all the objects of the world. Their primary aim is to prove that the Buddha has the knowledge of supersensuous truths and his teaching of Dharma is the means of attaining heaven and liberation. The knowledge of the Buddha is not hampered by obstacles because he is omniscient. The Buddhists dialectically establish the concept of human omniscience in order to prove the existence of a person who knows Dharma which is the means leading to heaven and freedom. 9 Their main aim is to prove that the authority for Dharma is the teachings of an omniscient teacher and only the Buddha is an omniscient religious teacher.

9Svargapavargasamprapti hetujno'sttti gamyate; Saksanna kevalam kintu sarvajno'pi pratiyate. Tattvasangraha (ed. by Pt. K. Krishnamacharya, Gai Baroda, 1926), Verse 3309.

CHAPTER I

THE CONCEPTION OF OMNISCIENCE IN THE VEDIC TRADITION

In this chapter we will attempt to trace the concept of omniscience in all of its multiple permutations throughout the Vedic tradition (viz. the Vedas, the Upani9ads, the schools of Vedanta, Sankhya, yoga, and Nyaya-Vai~e~ika). This is a necessary preliminary to enable one to understand the contrasting theories of omniscience in Buddhism and Jainism.

The Conception of Omniscience in the Vedas The concept of omniscience can be traced in the Vedas themselves. Many Vedic gods are conceived as omniscient. Although there is no mention of the word Sarvajna (omniscient), the other Sanskrit synonyms for omniscience are mentioned. The Sanskrit words with similar meanings are: Vi&vavit,l Vi~va-Vedas,2 Vi~va-Vidv~n~,3 Sarvavit,4 Vi~va-Chakshu,5 and Visva Drasta. 6 , , Such Vedic words have the implicit sense of the word omniscience. 1Rg. Veda, 19, 91, 31; Atharva Veda 1, 13, 4. ~igvedasamhita, with corny: of SNyana by F. M. MUller (London, 1892). 2Rg. Veda, 1, 21, l', Sarna Veda, 1, 1, 3. 3 Veda, 9, 4, 85, 10, 122, 2. ~g.

That is why the Vedic gods are sometimes referred 19

Both divine omniscience and human omniscience are found in the Vedas. The Vedas also ascribe omniscience to persons with supersensuous knowledge and supernatural power. It is evident from the Vedas themselves that the comprehension of supersensuous realities is possible; that is to say, a person can perceive or hear supersenuous truths like Dharma because of his omniscience.

A person with omniscience is called ~~i, one who has the intuitive realization of reality. The Vedic Gods are inspired sages (kavip). They too are ascribed with omniscience. The Vedic gods are beings enclawed with superSenSllQUS cognition. Themselves 8uperconscient, they have power to make others omniscient. In the Rg. Veda there is a description of the long-haired deities who are said to promote the vision of the Rsis. 7

to as the makers of Rsis (Rsikrt).

omniscient.

The gods Soma8 and Agni9 are called

The difference between a god and a -R.-s.-i is one of degree and not in the kind of power of omniscience. 10 Like Vedic gods, the R..sis also have the possibility of acquiring visionary knowledge of truth. The Vedic R..sis have knowledge of supersensuous truths. The 7Rg. Veda, 1, 164, 44.

knowledge ascribed to the -R.s.i-s is not discursive, nor ratiocinative, but has the nature of full-blo\Vll intuition. In the ~g. Veda the god Agni is considered to be omnipresent in the universe, in the sky, earth and waters. 11 He is also known as omn.lS.Clent (VvtlsIvavedas) . 12 He is also called thousand-eyed (Sahasr-aksa). 13 Furthermore, Agni is called the poet (Kavih). 14 He is also a mediator between man and gods,15 a Rsi inspired with vision. 16 -.-.- Agni is considered an omniscient god like Varuna. Varu~a is the omniscient god par excellence and Agni is both omnipresent and omniscient. 17 Agni has visional~ insight or omniscience. His omniscience is especially marked in the office of hot ar ,18 Agni has been also considered a divine being who promotes inspired thought and pro- vides omniscience to man. 19

Surya

Not only Agni but also the Surya is ascribed with the power of omniscience (vi£vacaksas) ,20 and "of wide vision" (urucaksas). 21 Sun is the eye of Mitra and Varuna. 22 He is also the eye of Heaven. 23 Varuna

The god Varuna is attributed with the power of omniscience. Varmla, the Orruliscient, sees all and makes revelations. 24

Varuna is

the upholder of the moral law (rta dhrta). He sits high above Gods and perceives all things. He governs the whole universe morally. Soma

The god Soma is all-knower (vi~vavid). He is the controller of the mind (Manasa Patih)25 and is endowed with a thousand eyes. 26 He has imnlediate insight into the nature of all things and is king of all worlds. 27

Vayu and Maruts

The wind god Vayu is omniscient like Agni and Varuna. His omniscience depends upon sight. Like Indra, Varuna and Agni, Vayu also has a thousand eyes. 28 In so far as Vayu goes everywhere and sees all things, he is omniscient as well.

In the Rg. Veda Dyayus (sky) is associated with Prithvi (earth), and is addressed as Dyavaprthivi (sky-earth). He is credited with ornn•lS•Clence ( V•lsI vavedas) . 29 Indra

Veda.

The god Indra is perhaps the most important deity of the ~. He is the all-perceiving god with manifold eyes (Sahasr-ak:a). 30 TI1US in the Vedas the concept of omniscience is a faculty of knowing which brings the intellect into intimate contact with every thing sensuous and supersenuous) the supersensuous reali~ies. Omniscience is not an attribute of all Vedic gods in general, but is specially an attribute of the sky gods and the gods who are connected with the heavenly realms of light. The Vedic gods are omniscient because their nature is self-luminous.

idea of self-realization of Brahman. The Upani~ads, however, do not give a comprehensive and elaborate account of the concept of omniscience. But they ma.lntalT. I t h at he Wh0 knows t he se lf , knows everythl.Ug. 31 The main stress is on the attainment of the knowledge of Atman (self). Thus, in the Upani~ads sarvajna means Atmajna (knower of the self). The word sarvaj~a is not used in the Vedas but it is frequently used in the Upanisads in the sense of Omniscience. The Conception of Onmiscience in the Advaita Vedanta Advaita Vedanta accepts the concept of human omniscience. By its nature, a jiva is not omniscient, but through spiritual discipline it can reach the state of omniscience which is penultimate to liberation. According to Sankara, omniscience should not be attributed to a liberated soul or Brahman. 32 However, he accepts that supernatural qualities like omniscience can be achieved by a person in the course of spiritual development by yoga. The supernatural qualities of Sagu~a Brahman, like omniscience, etc., can be achieved by a man (Saguua vidyavipaka sthanantvetat). Suresvara, in the commentary on Taittirlya Upani~ad, says that a human being can share in omniscience only through a relation with the divine, for omniscience is a divine quality and only God is omniscient and omnipotent. God's knowledge, like that of the yogi, is immediate. 33 31Yah Atmavid Sah Sarvavid, "Brhadaranyaka, Upani~ads, 4.5.6. 32 - - -

Sariraka-Bhasya (ed. by N. L. Shastri, Nirnaya Sagar Press, Bombay, 1927), 4,/f.6: . "Sarvajnatvam Sar've s va r a t varn ca .... na caitanyavat Svarupatva sambhavah".

The school of Advaita Vedanta maintains that the Saguna Brahman, who is the cause of the empirical world, is omniscient. 34

The liberated soul is not considered omniscient in Advaita Vedanta. Pure consciousness is the very nature of the soul. Neither bondage nor liberation of the soul is real; both are due to illusion. Only from an empirical standpoint is it said that a soul becomes free from bondage and becomes omniscient. However, in the state of liberation the soul becomes absolute non-dual consciousness. In this state the soul becomes pure consciousness and does not remain a knower. There is no otherness and there is nothing besides Brahman; therefore, it cannot know anything else but Brahman. The consciousness of outside objects is only due to ignorance, but in this state ignorance is completely annihilated. There is no object outside of it, so the liberated soul can know only itself. Consequently, Advaita Vedanta maintains that omniscience is not possible in the state of liberation.

Different Theories of Omniscience in the Advaita Vedanta The book Lights on Vedanta provides a detailed account of the concept of omniscience in the Advaita Vedanta. My interpretation of the concept of omniscience in Advaita Vedanta is based on this book. 35 34S-ar-iraka-Bh-asya, 2, 1, 14.

\~lereas the individual self is credited only with a limited knowledge, the Atman is credited with omniscience. Although Avidya is said to obscure the true nature of Atman and it projects the jiva, this obscuration does not alter the essential nature of the Atman which is described as both omniscient and omnipotent. These obscurations or limitations (kancuk) are four in number (kala, aVidya, raga, niyati). But the Advaitins emphasize the two primary limitations of the jiva, its limited knowledge, its limited power. The cognition of the jiva is restricted spatially, temporally, objectively, and can be divided into two categories: direct and indirect cognition. The immediate cognition of the jiva is dependent upon its various faculties or psychoses (vrtti); this is not the case with the Atman which is not dependent upon any faculty or vrtti. Rather, its omniscience operates without reference to any natural faculty (vrtti) of the jiva. The Advaitins have two theories concerning omniscience: one attributes omniscience to Atman itself which is pure consciousness and the other emanation or reflection of consciousness into the intellect (buddhi) which is a modification of mayi. - --

Bharatitirtha asserts that the Atman as consciousness, which is connected with its adjunct (upadhi) maya, contains the traces of all buddhis as their unchanging source and is capable of comprehending all their processes and content. The author of Praka.tartha also· upholds this second theory of omniscience and points to a parallelism between the cognition of the jlva via its adjunct (upadhi) antahkarara or mind and the omniscience of the Atman via its adjunct maya. In the former the cognition is nevertheless dependent upon i.ts psychoses or vrtti and arises only 26

with reference to external objects in the latter. The whole phenomenal world is upheld and transformed by virtue of maya, the adjunct of Atman. The buddhi or the reflection of the Atman as Cit operates in both cases, although it operates in an unlimited manner only in the latter.

~- Jnanaghana Pada, the author of Tattva-Suddhi establishes the omniscience of the Atman with respect to both future and past times and compares it to the memory of the jiva. Even before the emanation of the universe ~aya, because of the invisible powers (adrsta) of jivas, is changed into the prior apprehensions of all objects which are only later manifested. Brahman is the witness (saksi) of this transformation and indirectly acts as an agent for this transformation. So Brahman as Atman, reflected in the most subtle transformation of maya buddhi, has a prior knowledge of the whole phenomenal world. Just as past objects are cognized by recollection, so the total corpus of past phenomena can be cognized by the Atman by means of this creative association with maya and buddhi. We must distinguish between two classes of Vrtti. The first class or the Primordial Vrtti should be distinguished from the natural Vrtti which is diverse, discrete and empirically conditioned. The Primordial V:tti is all-encompassing and unlimited and immune from the limitations of empirical cognition. This Primordial Vrtti is the transformation of maya in situ and is associated with Atman as Cit (Cidan~a) and, together with the Sadansa (Truth-aspect), initiates the evolution of samsara, whereas the empirical Vrtti is the transformation of the mind, the necessary changes having been made, and it 27

acts together with the perceptive consciousness, Pramata or the jiva. This theory is critically scrutinized by Ramadvaya, the author of Vedanta-Kaumudi, who condemned this model of omniscience as unsatisfactory. Omniscience, being unconditioned and unlimited by nature, should not be described as conditioned by this Primordial Vrtti (or cognition through psychosis) and as reducible to a mere reflection of Atman in the buddhi. If it is so conditioned then instead of being unchanging and indestructible it would have to be described as destructible, as this Primordial Vrtti is subject to the same law of extinction as the gross elements. Such conditioning would then be transferred to omniscience itself, particularly to the omniscient Brahman as pure Consciousness (Cit). In this hypothetical situation, omniscience itself would perish which would paralyze the creative power of Brahman both with respect to its first transformation as maya, and also with respect to the gross elements preceded by iksana. Rather, he maintains that omniscience is the very nature of Brahman as pure Cit and is inherently capable of cognizing all that is created or manifested. It is capable of observing all that has been created or will be created in a spontaneous and unrestricted manner.

This is possible because the impressions of all things are preserved in maya like an unfinished picture. Thus to know maya completely through omniscience would entail knowing these impressions. Thus we can isolate three schools within Advaita. The Vivarana School maintains that the omniscient Atman can perceive the present object, through direct perception, the past object through memory and the future object through inference. Vacaspati repudiates both this 28

theory of omniscience associated with impressions or reflections, and the theory of omniscience which is associated with the Vrtti of maya. He maintains that omniscience is possible because of the selfconsciousness of Brahman 'Svar~pa Caitanya'. Consciousness cannot be described as any empirical product as it is one of the essential definitions of Brahman (Brahman as Cit). But consciousness, when linked to the perception of a particular object, is accomplished by Brahman. Thus the Atman is omniscient by nature, as all its objects of knowing are products of Brahman.

The third view is that of Suresvara who advocates a completely new theory which focuses on the necessity for I£vara to explain the possibility of omniscience. This explanation is dependent upon his Abhasa theory. All appearances of Brahman are possible only through the mediation of aVidya; specifically through the appearance of Sat or Cit in avidya. r,(vara as the Appearance of Cit through avidya, is the necessary causal link for all empirical entities and is described as naturally omniscient. Thus omniscience is explained by Suresvara without any reference to any modification of aVidya. The Conception of Omniscience in the Other Schools of Vedanta The dualists of the Vedanta School maintain a fundamental difference between the Brahman and the world. The finite souls and the material universe move according to the will of Brahman. Such a Brahman is omniscient, like the God of Nyaya. In the view of Visistadvaita, the Brahman is immanent in the world and is therefore omniscient. The Dvaitadvaita school holds that the Brahman is perfect 29

and all-embracing and that the finite Jivas are only imperfect forms of the Brahman. Undoubtedly, such a Brahman is omniscient. Dualistic Vedanta holds that omniscience can be attained after liberation. A liberated jiva becomes omniscient. This school maintains the difference between B~ahman and jiva and emphasizes that there cannot be any identity of the two. According to them, Brahman is determined and endowed with attributes (Saguna), unlike Nirguna •

Brahman. When the soul becomes liberated, it comes into inseparable association with Sagu~a Brahman; consequently, it acquires the omniscience and other qualities of Sagu~a Brahman. It seems that the omniscience attributed by these schools to the liberated soul is not of the same nature as the omniscience

- . I. J attributed to God by the schools of Nyaya, Valse~lka, Sesvara SaIDkhya, Yoga and Advaita Vedanta. The omniscience of God in these systems is eternal, unfettered and all-embracing. But the dualistic Vedantins believe that a jiva has a limited capacity for apprehension and that the jiva retains individuality at liberation and is not completely merged into God. Therefore, his limitations remain and he cannot become omniscient like God.

With his limited capacity, the liberated jiva does not have the ability to perceive constantly all cosmic things and the phenomena of all times and places as if they were always in the present. This type of omniscience is attributed to God, but it cannot be attributed to a jiva, because a jiva does not acquire all the powers of God. The maximum ability of a jiva is that he can know anything that he wants to know. In this sense alone he may be described as omniscient. 30

The Conception of Omniscience in the School of Yoga The school of Yoga emphatically stresses the purification of body, mind, and soul in order to achieve tranquility of mind (Citta). Patanjali mentions the vision of an enlightened person (siddhadar~anam)36 and states that as a result of meditation the yogi can discern everything (pratibhad va sarvam). According to the sub commentary of Vacaspatimisra37 on this passage, the intuitive knowledge of the yogin produces divine vision and leads to omniscience. This state is called pratibha, which is produced by the continued practice of concentration on the self. Therefore pratiblla is the supreme faculty of "omniscience". With the continued practice of concentration on the self, omniscience is gradually evolved.

By the continued practice of meditation, the Yogi is said to become omniscient in the last stage before self-realization. How this concentration leads to onmiscience is explained by the author of the conmlentary. According to the school of Yoga, the gunas are the essence of all things which have both the determinations and the objects of determinations as their essence, these gunas present themselves as being the essence of the object for sight in its totality to their owner, that is, the soul. 38 In other words, all things of the 36Yoga-Sutra (P-atanjala-Darsana) with Bhasya and Vyakhya (ed. Jivananda Vidyasagara, Calcutta, 1895), 3, 33. 37Ibid., 3, 36.

Yoga-Bhasya, 3, 49: "sarvatmano guna vyavasayavyavaseyatmakah svaminam ks e t r aj narh pratyasesardrsyatmatvenopasthitah". 31

universe and their knowledge are simultaneously revealed to the cosmic consciousness of the Yogi, because he reaches the state of selfconsciousness which is the state of omniscience. By gradually increasing his concentration a Yogi acquires the ability to perceive immediately (pratyaksa) the most remote or hidden or subtle or supersensuous things.

The school of Yoga accepts the omniscience of God39 in the sense that all objects of the universe, gross and subtle, past, present and future, are constantly in the knowledge of God in their perfect form and nothing is outside of his knowledge. The omniscience of God is permanent, but the omniscience of a Yogi is temporary, because it is gained by meditation and is lost when liberation is achieved and individuality is lost. Omniscience is not part of the natural endowment of the human soul and is only one of the achievements (siddhis) attained just before self-realization or liberation. TIle Conception of Omniscience in the School of Sankhya In the original early literature of Sankhya, we cannot find onmiscience attributed to either Prakrti or Purusa. However, according to the Jaina author Prabhacandracarya, in his book Prameyakamalamartanda, the cosmic principle Prakrti is held to be omniscient by some Sankhya philosophers. 40 They hold that Prakrti 39Tatra Niratisaya sarvajnatya bijam. Yoga-Sutra, Samadhipadah, 25.

40"Nikhila Jagatkartrttvaccasya Evasesajnattvamastu Prakrteh Sarvaj natyam Jagatkarttrtvam ceti Sankaprakarane". Prabha Chandra, Prameyakamalamartamda (ed. by Mahendra Kumar

as the creator of the world must necessarily be omniscient. The question arises concerning how unconscious Prakrti can be omniscient. Prakrti is unconscious and inactive before creation starts. Prakrti starts the world process when it comes into contact with conscious Purusa. On this basis they hold that the consciousness of Purusa .'

must also be reflected in -P-ra,k-rt-i. Although the consciousness of Prak;ti is not like the pure consciousness of Puru~a, Prak;ti as world creator must be regarded as omniscient. Intelligence and selfconsciousness are due to the derivative consciousness of Prakrti. The school of Sesvara Sankhya does not believe that Prak,rti becomes conscious at the time of creation. Therefore, they introduced God, who directs Prakrti toward the creation of the world in accordance with the Adrstas. According to them, this God is necessarily omniscient. In the original Sankhya school God is not mentioned. The liberated soul cannot become omniscient according to Sankhya because Purusa becomes disassociated from Prakrti in the state of liberation. However, they hold that a Yogi who is aspiring to liberation can achieve omniscience before liberation. They maintain that a Yogi acquires some supernatural ability to perceive by which he can apprehend the phenomena of all places and of all times. This is possible because they come into direct contact with Prakrti. Everything is evolved from Prakrti and everything is dissolved into Prakrti; nothing is outside Prakrti. Therefore, by seeing Prakrti he sees everything evolving out of it and dissolving into it. Thus a Yogi is able to perceive all things of the universe by coming into 33

contact W.lth t he un.lversa1 baS1.S 0 f a11 t h l.ngs, that 'lS, Praclrt'l. 41 , He establishes this contact through the practice of yoga. This supernatural power of a Yogi is called omniscience. Thus, the Sankhya philosophers do not believe in divine omniscience nor in the omniscience of a liberated soul, but they do believe in the omniscience of a person or Yogi who aspires to the achievement of liberation.

- I The Conception of Omniscience in the School of Nyaya Vaisesika The Nyaya and the Vaiiesika systems of philosophy maintain the theory of an omniscient and all-powerful God. Although, like the Samkhya philosophers, the Nyaya-Vai~esika systems admit the existence of an infinite number of eternal and uncreated souls, in the place of one Prak,rti they posit as an infinite number of atoms. According to the Naiyayikas, then, the world is constituted of an infinite nunilier of material atoms and an infinite number of souls, with Adrstas peculiar to each one of them.

The question thus arises: How do the bodies originate which are the means of the soul's varied worldly enjoyments and what is the originative cause of the physical world? Since the souls are by nature passive, they cannot create their bodies. The material atoms being inactive cannot create bodies either. Therefore, to explain the problem of world origination the Naiyayikas conceive of an all-powerful God, who creates the jiva in the body in order to experience the good and the bad fruits of their actions, and creates the world in order to function as the locus of such enjoyments. God's infinite intelligence is manifest in the world-process. The world is an effect (Karya) 34

of God's action. The effect is not automatic but caused. The cause is not material, but an effect of the intelligent cause that is God. In other words, an effect leads us to conclude that there is an intelligent agent behind it. God is thus the potter who is the efficient 42

cause of the pot (samsara).

The Naiyayikas conceive of God as necessarily omniscient. He makes a body and an environment for each soul exactly in accordance with its Adrsta. God not only creates the world but knows the purpose of creation. Creation is not a matter of blind chance but has purpose to be what it is. The world is a world of infinite possibilities. The possibilities of fruition and enjoyment presuppose a God with infinite intelligence and omniscience, for God must know what it is to be a God of infinite creative function.

The Nyaya-Vai~e~ika view of liberation (Apavarga) is an unconscious state. Just as omniscience is impossible in a being who has entered the state of Nirvana, similarly it is impossible in the state of absolute liberation to have consciousness. The Nyaya philosophy thus maintains that when liberation (Apavarga) is attained, all those attributes which are characteristics of the world (desire, pleasure, aversion, and effort, etc.) fall apart. In the state of liberation Juana or consciousness is absent like other attributes of the soul. The Vaiie~ikas also maintain that the state of liberation is a state of simultaneous annihilation of all its attributes, e.g., consciousness, etc. Like the expanse of sky, a liberated soul is unconscious. In the Nyaya-Vai~e?ika systems, a liberated soul thus cannot be omniscient. According to the Naiyayikas, the liberated soul has no 42

Isvarah kara~am puru~akarmaphalyadarsanat,Nyaya-Sutra, 4, 2. 35

consciousness. Consequently, the question of omniscience in an emancipated being does not arise. According to the Nyaya theory of knowledge it is impossible for the instrument (Karana) of knowledge to be simultaneously connected with more than one precept. Therefore, a simultaneous cognition of all things cannot be conceived. However, the Naiyayikas hold that the recollections of all things or the cause of the cognition of all things may simultaneously present themselves in a particular state of knowledge which relates to the whole collection of objects. Such a knowledge is constitutive of a totality of knowledge (samuhalambana) which is identical with omniscience. Silnilar to the Nyaya doctrine of samuhalambana is the Vai£e9ika conception of 'the knowledge of a seer' (Arsa-J~ana), which means omniscience.

The Concept of Omniscience in the School of Mimamsa The orthodox system of the Mimamsa is very firm supporter of the Vedas. It holds that only the Vedas are the omniscient authority for Dharma, because they are eternal and not written by any man. A human being cannot become omniscient because he is subject to moral, physical and intellectual limitations which cannot be transcended by any practice of ~a.

Taking omniscience as the necessary CUIldition for perceiving super-sensuous truths like Dharma, which cannot be known by the normal perception, the Mimamsakas, however, have attempted to prove the omniscience of the Vedas. The School of Mimamsa has raised many objections against tbe concept of human omniscience and the omniscience of the Buddha.

Here we shall see the objections lodged against the concept of omniscience by the Mimamsakas. The non-believers in omniscience like the Mimamsakas can raise three possible kinds of objections. The first objection concerns the proof for the existence of the omniscient person. The second objection concerns the nature of omniscience. The third objection concerns the relationship between omniscience and speech, which are considered contradictory to each other. Concerning the first type of objection, first, the existence of an omniscient person cannot be proved by any valid means of cognition. Second) in the whole world we do not at present see any omniscient person on the basis of which we can believe in the existence of an omniscient person in the past or in the future. Third, the achievement of omniscience, it is said, is possible by the means taught in the scriptures and the authority of the scriptures are accepted because they are revealed by an omniscient person. These are both mutually dependent assertions and cannot prove the existence of an omniscient person. Fourth, we do not find any valid proof to affirm or to negate the existence of an omniscient person. Therefore, the existence of an omniscient person is doubtful.

Regarding the second type of objection, it might first be asked whether the omniscient person perceives the objects of the world successively or simultaneously. If he perceives successively, there will never be a time when he will know all the objects of the world, because the objects will always continue to come into his cognition and his knowledge will remain incomplete. If he perceives simultaneously, he can have both omniscient and non-omniscient consciousness in a single cognitive moment of knowledge. Second, assuming he does know all the past, present and future things in a single moment, nothing remains to be kno'~l in the 37

second moment of consciousness. The second moment of cognition will be only a repetition of the first. Third, if the omniscient person can apprehend two opposite things like love and hatred in a single cognitive moment through his omniscient eye, then he himself should be associated with love and hatred. Fourth, if the omniscient person can perceive even the beginningless and endless objects, then the characteristic of beginninglessness and endlessness of those objects will be gone. In the third type of objection, omniscience and speech are considered to be contradictory; the presence of one implies the absence of the other. The speaker cannot be omniscient and the omniscient person cannot teach anyone or express his omniscience. These are the possible objections that have been lodged against the concept of omniscience by the school of ~ffmamsa. Thus we have seen how omniscience has been understood by the different Brahmanical schools. In the following chapter we shall examine the co-relative theories of omniscience in Jainism and Buddhism. This procedure will enable us to clarify the points of similarity and difference among the various schools in relation to this concept. CHAPTER II

THE CONCEPT OF OMNISCIENCE IN EARLY BUDDHISM

In this chapter we will attempt to trace the concept of omniscience in early Buddhism, especially in the Pali Nikayas. It has become a point of controversy among scholars whether in the earliest Pali Nikayas the Buddha was considered an OIDl1iscient religious teacher or whether he was just a religious teacher having the power of apprehending s upersensuous realities like dharma, heaven, rebirth, etc. In the earliest Pali Nikayas, which is generally considered to be the earliest Buddhist scripture, the Buddha cannot be said to be an omniscient religious teacher like Vardhamana, the Mahavira who was considered to be an omniscient religious teacher by the Jainas. However, the Buddha is depicted as an omniscient religious teacher in other works of early Buddhism and Mahayana Buddhism. According to the Dtgha-Nikaya, an Arhat possesses six kinds of supernatural knowledge (abhinna) . - - Although the Digha-Nikaya does not positively attribute omniscience to the Buddha, it does ascribe supernatural knowledge to him. The components of such a supernatural knowledge (abhinna) are as follows: clairaudience (dibbasota), thoughtreading (paracittavijanana), recollecting one's previous births (pubbenivasanussati), knowing other people's rebirths (sattanamcut~papata), certainty of emancipation already attained (asavakkhayakaranana), and clairvoyance with regard to the past and future of a living creature 38

(dibbacakkhu).l By this special wisdom the Buddha was able to know the doctrines of the previous Buddhas.

In the Digna-Nikaya, the following points can be gathered regarding the omniscience of the Buddha: (a) The Buddha does not deny, nor does he pos~tively affirm his omniscience -- omniscience understood in the sense of knowing everything. (b) The Buddha does disavow omniscience in the sense of knowing all things simultaneously (c) The Buddha does not claim an unlimited pure-cognitive knowledge of the future.

"It may happen, Cunda, that Handerers who hold other views than ours may declare: Concerning the past Gotama the Recluse reveals an infinite knowledge, and insight, but not so concerning the future, as to the what and the why of it". 2 (d) The Buddha owns Omniscience about the past; that is, his memory is unlimited.

ITNor does he in the Nikayas deny omniscience in the sense of knowing everything but not all at once. Yet it is clear that according to the earliest accounts in the Nikayas, the Buddha did not claim (an unlimited) precognitive knowledge. In the Pasadika Sutta, Digha Nikaya, it is said, 'It is possible that other heretical teachers may say "the Recluse Gotama has a limitless knowledge and vision with regard to the past but not with regard to the future" .... ' The Buddha goes on to explain that 'with regard to the past the Tathagata's consciousness follows in the wake of his memory' (atitam addhanam..• arabbha Tathagatassa satanusari vinna~aw hoti, loco cit.). He recalls as much as he likes (so yavatakam akankhati lDigha~Nikaya (ed. by T. H. Rhys Davids and J. E. Carpenter, 3 vol., PTS. London, 1890-1911), III, p. 281. 2Ibid., p , 134.

40

tavatakam anussarati, lac. cit.). 'With regard to the f~ture the Tathagata has the knowledge resulting from enlightenment that "this is the final birth.... " This appears to be an admission that the Buddha did not claim to have (at least an unlimited) precognitive knowledge of the future".3

(e) With regard to the future the Buddha claims to know that this was his last birth. Having once attained enlightenment he would not be born again.

"With regard to the future, the Tathagata has the knowledge resulting from enlightenment that 1 this is his final birth". 4

(f) The Buddha's knowledge is supposedly superior to that of Brahma in that the latter did not, or could not, know what the former knew. "The Great Br ahma , the Supreme One, the Mighty One, the All-seeing One, the Ruler, the Lord of all, the Controller, the Creator, the Chief of all, the Ancient of days, the

Father of all that are to be" could not answer.

In the Majjhima-Nikaya "s abbannu" (omniscient) and "sabba-das savt," (all seeing) were two controversial attributes at the time of the Buddha. These two terms are mentioned in a list of epithets falsely attributed to the Mahavira, the Jaina teacher:

"Vac cha , those who speak thus: the recluse Gotama is all knowing (sabbannu) and all seeing (sabbadassavi); he claims allembracing knowledge-and-vision, saying:

3K. N. Jayatilleke, Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge (G. Allen and Unwin, London, 1963), p. 469. 4 - - Digha-Nikaya, III, p. 134.

5I bi.d., I, p. 220.

41

'Whether I am walking, standing still or asleep or awake, knowledge-and-vision is permanently and continuously before met -- these are not speaking of me in accordance with what has been said, but they are misrepresenting me with what is untrue, not fact ll

• 6

However, the Buddha mentions that omniscience in the above sense is impossible:

"King Pasenadi spoke thus to the Lord: "I have heard this about you, revered sir: 'The recluse Gotama speaks thus: There is neither a recluse nor a brahman who, all-knowing, all seeing, can claim all-embracing knowledgeand- vision -- this situation does not exist". Further, the Buddha says:

"Those, sire, who speak thus ... do not speak as I spoke II •

He continues:

"I, sire, claim to have spoken the words thus: There is neither a a recluse nor a brahman who at one and the same time can know all, 7 can see all -- this situation does not ex~st" Vacchagotta asks the Buddha whether he was omniscient, like the Mahavira, who was claimed to possess a constant of everything: "As to this, Sand aka , some teacher, ,,11knowing, all-seeing, claims all-embracing

knowledge-and-vision, saying: '~~ether I am walking or standing still or asleep or awake, knowledge-and-vision is constantly and perpetually before me".8

6Majjhima-Nikaya (translated by I. B. Homer, 1967), p. 482. 7 - - -

"Nat th f so s amano va brahmano va va sakideva s abb an nassati sabbam dakkhiti n'etan thanaJ)l vijjati". Majjhima N., op . cit., II, p. 127.

8Ma],]'hl'ma-Nr 'kja-ya , op , c t't ,.I, , p , 482 • 42

The Buddha refuses this type of omniscience. Further, he says that what is claimed for the Jain leader is not true: "He enters an empty place, and he does not obtain alms food , and a dog bites him, and he encounters a fierce elephant, and he encounters a fierce horse, and he encounters

a fierce bullock, and he asks a woman and a man their name and clan, and he asks the name of a village or a market town and the wayll.9

The Buddha has claimed only "threefold-knowledge (tisso vijj a) for himself. He knows about the past birth of anyone: "For I, Vaccha, whenever I please, recollect a variety of former habitations, that is to say one birth, two births, ... thus do I recollect diverse former habitations in all

their modes and details".

He knows everything about the present life of a person: "For I, Vaccha, whenever I please, with the purified deva-vision surpassing that of men... see beings as they pass hence and come to be; I comprehend that beings are mean, excellent, comely, ugly, well-going, ill-going, according to the consequences of deeds".

He knows the future birth of anybody:

"And I, Vaccha, by the destruction of the cankers, having realised here and now by my own super-knowledge the freedom of mind and the freedom of wisdom that are cankerless, entering thereon, abide therein" .10

In the Majjhima-Nikaya we find a list of a hundred attributes of the 9I bi d., I, p. 519.

10Ibl·d., I , p. 482 •

Buddha, but the epithet "sabbannu" and "sabbadassavi" are conspicuous bY t h el· r ab sence. 11

In the Samyutta-Nikaya the Buddha has been worshipped as the highest and holiest person. 12 He is the wisest teacher of gods and men, because he has conquered all the power of darkness. 13 He himself declares that knowledge has arisen in him: "It has arisen in me! It has arisen in me! °brothers. I have been blessed with the eye by which I can observe things which have not been taught before. Knowledge has

arisen in me, insight has arisen in me, wisdom has arisen in me, light has arisen in me",14

In the Samyutta-Nikaya there is a parable of Simasapa leaves. This parable is very revealing, although very easily misunderstood, with regard to the Buddha's onmiscience. The Buddha takes a handful of leaves and says that what he has taught is like the leaves in his hand, and what he did not teach is like the leaves in the forest. "Just so, monks, much more in number are those things I have found out, but not revealed; very few are the things I have revealed. And why, monks, have I not revealed them?

"Because they are not concerned with profit, they are not rudiments of the holy life, they conduce not to revlusion, to dispassion, to cessation, to tranquility, to full comprehension, to the perfect wisdom, to Nibbana.

That is why I have not revealed them" .15 llIbid., I, p , 482.

12Samyutta-Nik-aya (translated by F. L. Woodward, 1925), I, p. 47. l3 Ibi d., I, pp. 50, 132.

Certain significant implications could be drawn from this parable of the Simasapa leaves. In the first place, it is obvious that the Buddha claims to know much more than he actually taught. But to claim to know much more than one teaches is not the same as claiming omniscience. Infinity of knowledge and omniscience are logically two things; the former is possible without the latter. Also, the Buddha contends that his knowledge could not be doubted or challenged by an ordinary man ruled by passions. This, again, does not in fact imply that the Buddha was claiming omniscience, or that Buddha was wrong in according indubitability to his knowledge which was not omniscient. Knowledge of the dharma is possible without omniscience.

The Buddha reprimandingly warns a monk who was doubting his teaching of dharma:

"It is possible that some senseless fellow, sunk in ignorance and led astray by craving, may think to go beyond the Master's

teaching .... "16

In the Anguttara-Nikaya the Buddha has been considered superior to all the other beings because he has acquired knowledge of the ultimate truth. However, he is neither a god, nor a semi- 17 divine being nor a man.

There is a parable in the Allguttara-Nikaya where the monk Uttara compares the Buddha's teachings with a granary. 16Samyuttara-Nik-aya, ~. cit., III, 103. l7Anguttara-Nikaya (translated by E. M. Hare, London, 1961), II, 38.

"If there is a granary in the vicinity of a village or hamlet and people were to carry grain in pingoes, baskets, in their robes and hands ... then if one were to ask the question 'from where are you carrying this grain', the proper reply would be to say that it was from this large granary".

Further, he concludes that whatever words are spoken by him are only an echo of the words of the Buddha:

"Even so, whatever is well-spoken is the word of the Exalted One".lS

This parable involves a profound intent, although in a simple form, for here also the infinity of the Buddha's knowledge may be easily confused with his olmliscience. In this parable, Uttara accepts the superiority of the Buddha's knowledge and compares the Buddha with a large granary where one could collect grains according to the capacity and the space of his basket. Also, the fact that the Buddha's teachings are acknowledged as well-spoken does not imply that it is all that could be spoken, or that it is all that the Buddha would speak, or that the Buddha is omniscient. Although the Anguttara-Nikaya is significantly silent on the matter of the omniscience of the Buddha, it explicitly ascribes six intellectual powers and three-fold knowledge to him. The Buddha knows: (a) What is possible as possible. (b) What is impossible as impossible. (c) The effects according to their conditions and causes. (d) Performance of karma in the past, present and future. (e) Corruption and perfection. (f) Concentration and attainment of nirvana. lSIbid., IV, 164.

"While the Aggi-Vacchagotta Sutta mentioned that the Tathagata had a three-fold knowledge, we find it mentioned in one place in the Allguttara that 'there are six intellectual powers of the Tathagata' (cha yimani ... Tathagatassa Tathagatabalani, A. III. 417). The six constitute, in addition to the

three-fold knowledge, the following: (i) 'the Tathagata knows, as it really is, what is possible as possible and what is impossible as impossible' ( ... Tathagato thanan ca . thanato atthanan ca atthanato yathabhutam pajanati,·ioc. cit.),·Cii) 'the Tathagat~ knows as it really is, the effects according to their conditions and causes, of the

performance of karma in the past, present and future' ( ... Tathagato atitanagatapaccupannanam kammasamadananam thanaso hetuso

vipakam y~thabhutam hajanati: loco cit.), and (iii) 'the Tathagata knows~s it really is, the corruption, perfection and arising from contemplative states of release, concentration and attainment' ( .. ,Tathagato

jhanavimokkhasamadhisamapattinam saml<ilesam vodanam vutthanam yathabhutam p~jan~ti, lo~. cit.),,:19 •• .

Sutta-Nipata does not attribute the concept of omniscience to the Buddha. However, it accepts him as the perceiver of everything, 20 because he is an all-enlightened sage. He is an all-seeing one who 21 removes all darkness, and he has proclaimed the doctrine of the truth on earth. 22

In the Vinaya Pitaka, it is said that the Buddha has become the embodiment of vision, not only this, but also he has become 19K• N. Jayatilleke, Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge,

knowledge, dhamma and even Brahma, etc. It is also said that there are some disciples who have become the embodiment of reason. The Kathavatthu of Abhidhamma-Pitaka, which goes one step further than the Diggha-Nikaya and Majjhima-Nikaya, attributes onmiscience to the Buddha: "Conqueror, Master, Buddha Supreme, All-knowing (Sabbanna) , All-seeing (Sabbadassavi), Lord of the Norm, Fountain-head of the Norm".23

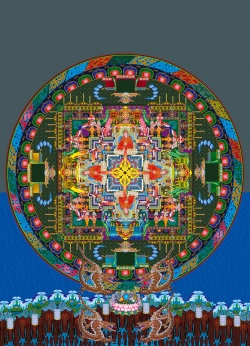

The Patisambhida-Magga clarifies the nature of omniscience attributed to the Buddha: "What is meant by the omniscience of the Tathagata" (katamam 'I'athagatas aa s abb annut anau 131). Omniscience consists in "knowing everything conditioned and unconditioned without remainder" (sabbam sankhatam assankhatam anavasosam janati ti, 131) and in "knowing everything in the past, present and future" (atftam••• anagatam... paccuppannam sabbam j anati ti, p. 131). The passage continues giving the components of the Buddha's omniscience, the last of which is "he knows everything that has been seen, heard, sensed, thought, attained, sought and searched by the minds of those who inhabit the entire world of gods and men" (Yavata sadevakassa lokassa..• dittham sutam mutam vinnatam patjam pariyesitam anuvicaritam manas-a sabbam ja- n-ati., 131). 24

The Niddesa, the eleventh book of the Khuddaka-Nikaya, goes positively further than the earlier claims of the Pali Nikayas. The 23Katha Vatthu, III, 1, translated by S. Z. Aung and Mrs. R. Davids, 1969.

24K. N. Jayatilleke, op . cLt , , p. 380. 48

earlier Pali Nikayas maintain that it is impossible to know all things all at once. It is still conceded that the Buddha's olnniscience is not like that of the Mahavira. It is said that the knowledge of each and every thing is constantly present in the mind of the Mahavira. Although the omniscience of the Buddha is not like that of the Mahavira, it is accepted that the Buddha can encompass the whole within his consciousness. The all-seeing eyes of the Buddha are called omniscience. Nothing remains unseen by the Buddha, because he possesses the all-seeing eyes. 25

In the Udana the Buddha's oW1iscience has been given three meanings. They are as follows: (a) That the Buddha knows more than the ordinary people do. (b) That the Buddha's knowledge surpasses the knowledge of other recluses, Brahmans and wanderers. (c) That the Buddha's knowledge is not partial, but is total and the whole vision of reality:

"Thereupon, monks, that rajah went up to the blind men and said to each, 'Well, blind man, have you seen the elephant?' 'Yes, sire.' 'Then tell me, blind men, what sort of thing is an elephant.' Thereupon those who had been presented with the head answered, 'Sire, an elephant is like a pot.' And those who had observed an ear only replied. 'An

elephant is like a winnowing-basket. ' .... Then they began to quarrel, shouting, 'Yes, it is!. 'No, it is not!' IAn elephant is not that!' 'Yes, it's like that!' and so on, till they carne to fisticuffs over the matter .••. Just so are these Wanderers holding other views, blind, unseeing, knowing not the profitable, knowing not the unprofitable. They know not dhamma , They know not what 25

is not dhamma. In their ignorance of these things they are by nature quarrelsome,