Difference between revisions of "Why Tantra Is More Efficient Than Sutra"

(Created page with " Gelug Presentation of Tantra in General Methodology Tantra is well known as being a quicker and more efficient method for achieving enlightenment than is sutra. To ap...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

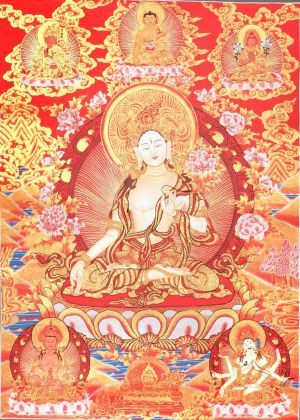

| + | [[File:7065428 n.jpg|thumb]] | ||

| Line 4: | Line 5: | ||

| − | Gelug Presentation of Tantra in General | + | ==[[Gelug]] Presentation of [[Tantra]] in General== |

| − | Methodology | + | =={{Wiki|Methodology}}== |

| − | Tantra is well known as being a quicker and more efficient method for achieving | + | [[Tantra]] is well known as being a quicker and more efficient method for achieving [[enlightenment]] than is [[sutra]]. To appreciate [[tantra]] and put full [[enthusiasm]] into its practice in a {{Wiki|realistic}} manner, it is important to know what makes [[tantra]] so special. We can discuss this on several levels, depending on the [[tantra class]] and specific [[tantra]]. Here, however, let us speak of only three levels: |

| − | enlightenment than is sutra. To appreciate tantra and put full enthusiasm into its practice in a | ||

| − | realistic manner, it is important to know what makes tantra so special. We can discuss this on | ||

| − | several levels, depending on the tantra class and specific tantra. Here, however, let us speak of | ||

| − | only three levels: | ||

| − | 1. tantra in general - common to all four tantra classes, | + | 1. [[tantra]] in general - common to all four [[tantra]] classes, [[anuttarayoga tantra]] in general - common to the main [[anuttarayoga tantras]], such as [[Guhyasamaja]], |

| − | anuttarayoga tantra in general - common to the main anuttarayoga tantras, such as | ||

| − | Guhyasamaja, | ||

| − | 3. Kalachakra tantra. | + | ==3. [[Kalachakra tantra]].== |

| − | On each level, we shall analyze four reasons for its enhanced speed: | + | On each level, we shall analyze four [[reasons]] for its enhanced {{Wiki|speed}}: |

1. There are closer analogies within the practice. | 1. There are closer analogies within the practice. | ||

| − | 2. There is a closer union of method and wisdom. | + | 2. There is a closer [[union of method and wisdom]]. |

| − | 3. There is a special basis for voidness used for gaining the understanding of voidness. | + | 3. There is a special basis for [[voidness]] used for gaining the [[understanding]] of [[voidness]]. |

| − | 4. There is a special level of mental activity used for perceiving voidness. | + | 4. There is a special level of [[mental activity]] used for perceiving [[voidness]]. |

| − | We shall use as our basis the Gelug presentation of the subject matter, as found in A Grand | + | We shall use as our basis the [[Gelug]] presentation of the [[subject]] {{Wiki|matter}}, as found in A Grand Presentation of the Stages of Hidden [[Mantra]] ([[sNgags-rim chen-mo]]) by the fourteenth-century [[master]] [[Tsongkhapa]] ([[Tsong-kha-pa Blo-bzang grags-pa]]). The four-point analysis has been extrapolated from salient points in this text, although [[Tsongkhapa]] himself has not structured his [[discussion]] in this manner. As a supplement, we shall indicate the features unique to the explanations given in the non-Gelug systems - [[Sakya]], [[Kagyu]], and [[Nyingma]] - when they significantly differ. |

| − | Presentation of the Stages of Hidden Mantra (sNgags-rim chen-mo) by the fourteenth-century | ||

| − | master Tsongkhapa (Tsong-kha-pa Blo-bzang grags-pa). The four-point analysis has been | ||

| − | extrapolated from salient points in this text, although Tsongkhapa himself has not structured | ||

| − | his discussion in this manner. As a supplement, we shall indicate the features unique to the | ||

| − | explanations given in the non-Gelug systems - Sakya, Kagyu, and Nyingma - when they | ||

| − | significantly differ. | ||

| − | (1) Closer Analogies | + | ==(1) Closer Analogies== |

| − | The practices of both bodhisattva sutra and general tantra act as causes for reaching the goal | + | The practices of both [[bodhisattva]] [[sutra]] and general [[tantra]] act as [[causes]] for reaching the goal of [[enlightenment]], with the [[attainment]] of the [[physical]] corpuses (Skt. [[rupakaya]], [[form bodies]]) and [[omniscient]] all-loving [[mental activity]] (Skt. [[dharmakaya]]) of a [[Buddha]]. The causal practices in each, however, resemble the goal to different degrees. |

| − | of enlightenment, with the attainment of the physical corpuses (Skt. rupakaya, form bodies) | ||

| − | and omniscient all-loving mental activity (Skt. dharmakaya) of a Buddha. The causal | ||

| − | practices in each, however, resemble the goal to different degrees. | ||

| − | In Sutra | + | ==In [[Sutra]]== |

| − | The bodhisattva sutras discuss the two enlightenment-building networks (tshogs-gnyis, the | + | The [[bodhisattva]] [[sutras]] discuss the two enlightenment-building networks (tshogs-gnyis, the [[two collections]]) as [[causes]] for achieving a [[body]] and [[mind of a Buddha]]. These are the networks of positive force ([[bsod-nams]], Skt. [[punya]], [[merit]], positive potential) and [[deep awareness]] ([[ye-shes]], Skt. [[jnana]], [[wisdom]], [[insight]]). Each is a network in the [[sense]] that its constituents connect with and reinforce one another, rather than just [[accumulate]] as members of a passive collection. |

| − | two collections) as causes for achieving a body and mind of a Buddha. These are the networks | ||

| − | of positive force (bsod-nams, Skt. punya, merit, positive potential) and deep awareness | ||

| − | (ye-shes, Skt. jnana, wisdom, insight). Each is a network in the sense that its constituents | ||

| − | connect with and reinforce one another, rather than just accumulate as members of a passive | ||

| − | collection. | ||

| − | We build up the two enlightenment-building networks exclusively with a bodhichitta | + | We build up the two enlightenment-building networks exclusively with a [[bodhichitta]] [[motivation]] beforehand and a [[dedication]] to [[enlightenment]] afterward. Otherwise, our constructive ([[dge-ba]], [[virtuous]]) [[actions]] and [[meditation]] on [[the nature of reality]] constitute only samsara-building networks of positive force and [[deep awareness]]. Such networks serve merely as [[causes]] for achieving a [[body]] and [[mind]] in one of the better [[rebirth]] states. |

| − | motivation beforehand and a dedication to enlightenment afterward. Otherwise, our | ||

| − | constructive (dge-ba, virtuous) actions and meditation on the nature of reality constitute only | ||

| − | samsara-building networks of positive force and deep awareness. Such networks serve merely | ||

| − | as causes for achieving a body and mind in one of the better rebirth states. | ||

| − | The minimum level of bodhichitta required for our constructive actions and meditation to | + | The minimum level of [[bodhichitta]] required for our constructive [[actions]] and [[meditation]] to constitute enlightenment-building networks is a labored (rtsol-bcas) [[state]], reached by relying on a line of {{Wiki|reasoning}}. With the [[attainment]] of unlabored ([[rtsol-med]]) [[bodhichitta]], which arises without such reliance, we become [[bodhisattvas]]. |

| − | constitute enlightenment-building networks is a labored (rtsol-bcas) state, reached by relying | ||

| − | on a line of reasoning. With the attainment of unlabored (rtsol-med) bodhichitta, which arises | ||

| − | without such reliance, we become bodhisattvas. | ||

| − | An extensive enlightenment-building network of positive force serves as the obtaining cause | + | An extensive enlightenment-building network of positive force serves as the obtaining [[cause]] ([[nyer-len-gyi rgyu]]) for the [[body]] of a [[Buddha]]. An obtaining [[cause]] is the item from which we obtain the result. It functions as the natal source ([[rdzas]], natal [[substance]]) giving rise to the result as its successor. It ceases to [[exist]] |

| − | (nyer-len-gyi rgyu) for the body of a Buddha. An obtaining cause is the item from which we | ||

| − | obtain the result. It functions as the natal source (rdzas, natal substance) giving rise to the | ||

| − | result as its successor. It ceases to exist | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | simultaneously with the [[arising]] of its result. For example, a seed is the obtaining [[cause]] for a sprout. Obtaining [[causes]] and their results, however, do not need to be [[forms]] of [[physical phenomena]]. Today's [[understanding]] of a [[Dharma]] point, for instance, is the obtaining [[cause]] that gives rise to tomorrow's [[understanding]] of it. Obtaining [[causes]] need simultaneously acting [[conditions]] (lhan-cig byed-rkyen) in order to give rise to their results. Here, | ||

| − | + | an enlightenment-building network of positive potential requires as a simultaneously acting [[condition]] an enormous enlightenment-building network of [[deep awareness]]. Likewise, an extensive enlightenment-building network of [[deep awareness]], as the obtaining [[cause]] for the [[mind of a Buddha]], requires a vast enlightenment-building network of | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | positive force as its simultaneously acting [[condition]]. The pair of enlightenment-building networks is required for achieving either of the two, a [[body]] or a [[mind of a Buddha]]. [For a more advanced [[discussion]], see: Relationships between Two [[Objects]] in General {2} {5}.] | ||

| − | |||

| + | Although the sutra-level [[causes]] for [[enlightenment]] are somewhat like their results, they are not so similar. For instance, a [[Buddha's]] [[physical body]] has thirty-two major features that are indicative of their [[causes]]. A [[Buddha's]] long {{Wiki|tongue}}, for example, indicates and represents the type of [[love]] with which he or she, in [[previous lives]] as a [[bodhisattva]], took [[care]] of others like a mother [[animal]] licking her young. Working with such [[causes]] alone requires three [[zillion]] (countless) [[eons]] to reach the goal. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==General [[Tantra]] as the [[Resultant Vehicle]]== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | In general [[tantra]], the obtaining [[causes]] for [[attaining]] the [[enlightening]] [[body]] and [[mind of a Buddha]] are more analogous to the results we wish to attain. We practice now as if we had already achieved our goals. Because of this feature, [[tantra]], as the "[[resultant vehicle]]," is more efficient for reaching [[enlightenment]]. | ||

| − | |||

| + | [[Tantra practice]] resembles a dress rehearsal. If we wish to [[dance]] in a ballet, we need to attend ballet school first and learn to [[dance]]. The obtaining [[cause]], however, that functions as the natal source giving rise to the actual performance as its immediate successor, is the dress rehearsal of the ballet. Likewise, if we wish to [[practice tantra]], we need to learn and develop first the [[essentials]] from [[sutra]]. Subsequent [[tantra practice]] is like the dress rehearsal to combine the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==In [[Sutra]]== | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[essentials]] to bring us to [[enlightenment]] as its immediate successor. In all classes of [[tantra]], then, we simulate four [[purified]] factors (rnam-par dag-pa bzhi) we will have as [[Buddhas]]. They are [[purified]] of all [[suffering]] and the [[causes of suffering]], in the [[sense]] that they arise in our [[experience]] when we have achieved a true stopping (' gog-bden, [[true cessation]]) of both. The four are | |

| − | |||

| − | + | 1. [[purified]] [[bodies]], | |

| + | 2. [[purified]] environments, | ||

| − | + | 3. [[purified]] manners of experiencing [[sense objects]] with [[enjoyment]] (longs-spyod), | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | 4. [[purified]] [[actions]]. | ||

| − | |||

| + | We do this by [[Wikipedia:Imagination|imagining]] that we have all four factors now. Using our [[imaginations]] ([[dmigs-pa]]) in these ways acts as a [[cause]] to achieve the four [[purified]] factors more quickly. Most [[translators]] call this process "[[visualization]]." The term, however, is a bit misleading, because the process is not merely [[visual]]. It involves the entire scope of our [[imaginations]] - [[Wikipedia:Imagination|imagining]] sights, {{Wiki|sounds}}, {{Wiki|smells}}, {{Wiki|tastes}}, [[physical]] [[sensations]], [[feelings]], [[emotions]], [[actions]], and so on. [[Tantra]] harnesses the power of [[imagination]] - an extremely potent tool we all possess. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==[[Purified]] [[Bodies]]== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In [[tantra]], we [[imagine]] that we have [[purified]] [[bodies]] like those of one of the [[Buddha-figures]] - the many [[forms]] in which an [[enlightening]] [[body]] can appear. As the {{Wiki|etymology}} of [[yi-dam]], the [[Tibetan]] [[word]] for [[Buddha-figure]], implies, we "bond our [[minds]] closely" with them in daily practice in order to reach [[enlightenment]]. Thus, we [[imagine]] our [[bodies]] are transparent, made of [[clear light]], and able to multiply into countless replica [[bodies]], all with the [[infinite]] [[energy]] and capabilities of those of a [[Buddha]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Moreover, we do not [[imagine]] ourselves as [[Buddha-figures]] merely during [[meditation]] sessions. We try to maintain [[mindfulness]] ([[dran-pa]]) on this the entire day. [[Mindfulness]] is a [[subsidiary awareness]] ([[sems-byung]], [[mental factor]]) that accompanies [[cognition]] of something. Like a "[[mental glue]]," it prevents our [[attention]] from losing its [[object]]. | ||

| − | + | With [[mindfulness]], we maintain both the clarity ([[gsal-ba]]) and [[self-esteem]] or [[dignity]] ([[nga-rgyal]], [[pride]]) of the [[Buddha-figure]]. Clarity is the [[mental activity]] of producing the [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] [[appearance]] of the [[Buddha-figure]], regardless of level of clarity of detail or focus. [[Self-esteem]] is the [[mental activity]] of labeling "me" on the continuity of the [[appearance]] of the figure and [[feeling]] that this is who we actually are. | |

| + | [[Tsongkhapa]] emphasized that maintaining [[mindfulness]] on the [[self-esteem]] of being the figure is more important at first than trying to gain clarity of detail and maintaining [[mindfulness]] on the detail. To begin, we need merely achieve a rough clarity of [[visualization]], to serve as the basis for labeling (gdags-gzhi) "me." | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==[[Tantric Transformation]] of Self-Image== | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | While [[visualizing]] ourselves as [[Buddha-figures]], we also [[imagine]] that we have the self-images associated with the figures. Many [[people]] have negative self-images, for instance as not being good enough or not deserving to be [[happy]] or loved. In contrast to such negative self-images, | |

| − | + | ==[[Buddha-figures]] imply positive ones.== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==General [[Tantra]] as the [[Resultant Vehicle]]== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In [[Buddhism]], negative and positive do not denote bad and good. Rather, they imply {{Wiki|destructive}} and constructive. {{Wiki|Destructive}} means ripening into problems and [[suffering]], in this [[life]] and {{Wiki|future}} ones, through a process of leaving a legacy ([[sa-bon]], seed, tendency) and [[Wikipedia:Habit (psychology)|habit]] ([[bag-chags]], {{Wiki|instinct}}) on our [[mental]] continuums. Constructive means ripening into [[happiness]] through a similar process. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | [[Buddha-figure]] practice resembles, in a [[sense]], a type of "[[mental]] [[judo]]" with which we work with the {{Wiki|tendencies}} of our [[minds]] to project self-images. Instead of projecting negative ones, we project positive self-images instead. Each [[Buddha-figure]] has a positive {{Wiki|self-image}} associated with it. For example, [[Avalokiteshvara]] represents being a | ||

| − | + | warm, [[loving]], and [[compassionate]] [[person]]; [[Manjushri ]](' [[Jam-dpal]] dbyangs), being someone clearheaded and able to understand everything. We practice with one or another figure in order to {{Wiki|emphasize}} a specific positive {{Wiki|self-image}}, in accordance with our dispositions and needs. | |

| − | + | Moreover, each [[Buddha-figure]] represents not only a certain aspect of a [[fully enlightened being]], but also the entirety of an [[enlightened state]]. Thus, practice of just one [[Buddha-figure]] is sufficient for reaching [[enlightenment]]. Most practitioners, however, work with a variety of [[Buddha-figure]] systems to gain the advantages of the special features of each. The [[tantric]] method of [[transforming]] our self-images is not simply using "the power of positive [[thinking]]." The change of {{Wiki|self-image}} derives from [[understanding]] the [[Buddha-nature]] factors and the [[voidness]] of ourselves, these factors, and all self-images we may have. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | self-nature | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==The [[Voidness]] of Self-Images== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Moreover, | + | From the point of view of our [[Buddha-natures]], we all have the potentials for becoming [[Buddhas]], as the self-images of the [[Buddha-figures]] represent. Moreover, negative and positive self-images are equally devoid of [[existing]] in impossible ways, as do we and our potentials. The impossible manner is with [[true existence]] (bden-grub, truly |

| + | established [[existence]]). According to the [[Prasangika-Madhyamaka]] theories, [[true existence]] means [[existence]] established by the power of something on the side of a [[phenomenon]] and not merely by [[mental]] labeling alone. Truly established [[existence]] is thus {{Wiki|equivalent}} to [[existence]] established by [[self-nature]] ([[rang-bzhin-gyis grub-pa]], | ||

| − | + | [[inherent existence]]). This means that when valid [[cognition]] scrutinizes the [[superficial]] [[truth]] of something, it finds, on the side of the scrutinized [[phenomena]], the referent "thing" ([[btags-don]]) [[corresponding]] to the [[name]] or | |

| − | + | label for the [[phenomenon]]. This is also {{Wiki|equivalent}} to saying that [[phenomena]] have their [[existence]] established by {{Wiki|individual}} defining [[characteristic]] marks (rang-mtshan-gyis grub-pa), which are findable on the side of the [[phenomena]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | For example, we may [[feel]] that there is something inherently bad or good inside us that, by its [[own]] power, makes us [[exist]] as bad or good persons. We and any self-images we may have are equally devoid of [[existing]] in that manner, because there is no such thing as truly established [[existence]] - it is an impossible manner in which anything could [[exist]]. | |

| − | + | Moreover, everything is devoid of all four extreme modes of impossible [[existence]]: | |

| − | + | 1. [[true existence]] - the {{Wiki|eternalist}} position, | |

| − | |||

| + | 2. total [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] - the [[Wikipedia:Nihilist|nihilist]] position, | ||

| − | + | 3. both - from one point of view {{Wiki|eternalist}}, from another [[Wikipedia:Nihilist|nihilist]], | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==[[Tantric Transformation]] of Self-Image== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | neither - from one point of view, a manner of [[existence]] that is not {{Wiki|eternalist}}; from another viewpoint, one that is not [[Wikipedia:Nihilist|nihilist]] either. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | 4. If asked how self-images actually [[exist]], all we can say, according to the uniquely Gelug-Prasangika view, is that, {{Wiki|conventionally}} (tha-snyad), self-images do [[exist]], but simply by [[virtue]] of [[mental]] labeling or [[imputation]] alone (btags-pa 'dog-tsam-gyis grub-pa). More fully, they [[exist]] as merely what the words and [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] for them | |

| − | + | refer to (btags-chos), based merely on a valid [[imputation]] of them on a valid basis for labeling (gdags-gzhi). There are no such things as [[Buddha-nature]] factors, or self-images representing them, findable inherently inside us that by their [[own]] [[powers]], or in {{Wiki|conjunction}} with our [[thinking]] about them, makes us good persons. Nevertheless, we may validly label them on our [[mental]] continuums based on our [[experience]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | We may likewise validly label negative potentials and negative self-images based on the [[experiences]] of our [[mental]] continuums. Nevertheless, negative aspects derive from fleeting stains (glo-bur-gyi dri-ma) that temporarily obscure our [[Buddha-natures]] - such as [[confusion]] about how we, others, and everything around us [[exist]]. The fleeting | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | stains are removable with accurate [[understanding]] of [[reality]], specifically with [[nonconceptual cognition of voidness]]. On the other hand, the continuities of our [[Buddha-natures]] go on forever, with no beginning and no end. Therefore, positive self-images can permanently replace negative ones. | ||

| − | |||

| + | [[Buddha]] [[taught]] not to accept these points on the foundation of [[blind faith]]. Accurate [[understanding]] of [[reality]], corroborated by valid [[inferential cognition]] ([[rjes-dpag tshad-ma]]) and valid straightforward [[cognition]] ([[mngon-sum tshad-ma]]), supports these [[truths]] and both dislodges and abolishes the confused [[belief]] that negative qualities are | ||

| − | + | our true natures. Thus, a deep [[understanding]] of the [[four noble truths]] ([[four truths]] of [[life]]) - true problems, their true [[causes]], their true stopping, and the true pathway [[minds]] that bring that about - is [[essential]] for a correct [[tantric]] [[transformation]] of {{Wiki|self-image}}. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==In the context of our [[discussion]], we may formulate the [[four noble truths]] as:== | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | 1. uncontrollably recurring [[rebirth]] is the true problem; [[belief]] in [[truly existent]] negative self-images, based on [[confusion]] about [[reality]], is the [[true cause]]; | |

| − | + | 3. removal forever of this fleeting stain from our [[Buddha-natures]] is a true stopping; [[nonconceptual cognition of voidness]] and of our [[Buddha-natures]] is the true [[pathway mind]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Mantras]] | |

| − | + | Each [[Buddha-figure]] also has one or more associated [[mantras]]. [[Mantras]] are sets of {{Wiki|syllables}} and, often, additional [[Sanskrit]] [[words and phrases]], all of which represent [[enlightening]] {{Wiki|speech}}. While repeating the [[mantras]] of a [[Buddha-figure]], we [[imagine]] we have the {{Wiki|abilities}} to {{Wiki|communicate}} perfectly to everyone the complete means for eliminating [[suffering]] and reaching [[enlightenment]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Mantras]] also shape our [[breath]], and consequently our [[subtle energy-winds]], enabling us to bring the [[winds]] under control for use in [[meditation practice]]. From a [[Western]] viewpoint, they have certain vibration frequencies that affect our energies and, consequently, our [[states of mind]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==The [[Voidness]] of Self-Images== | ||

| − | + | ==[[Purified]] Environments - [[Mandalas]]== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | We also [[imagine]] that we have the [[purified]] environments of the [[Buddha-figures]]. [[Mandalas]] represent those environments. They are three-dimensional {{Wiki|palaces}}, with the [[Buddha-figures]] in their centers and often many secondary figures around - some {{Wiki|male}}, some {{Wiki|female}}, some {{Wiki|solitary}}, and some as couples. Two-dimensional depictions | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | of [[mandalas]], whether painted on cloth or made from colored powders, are like architectural blueprints for the {{Wiki|palaces}}. We [[imagine]] that we are not just the central figure, but all the [[Buddha-figures]] of the [[mandala]]. We also envision complete [[purified]] lands (dag-zhing) surrounding the {{Wiki|palaces}}, where everything is conducive for reaching [[enlightenment]] through [[tantra practice]]. | ||

| − | Purified | + | ==[[Purified]] Manner of [[Enjoyment]]== |

| − | + | Moreover, we [[imagine]] that we are able to [[experience]] [[sense objects]] with [[enjoyment]] in the way that [[Buddhas]] do, untainted by any [[confusion]] (zag-med-kyi [[bde-ba]], uncontaminated [[happiness]]). Normally, we [[experience]] things [[tainted]] with [[confusion]]. When we listen to [[music]] at home, for instance, we may be unable to enjoy it purely without fretting that our [[sound]] systems are not as good as those of our neighbors. We may be [[attached]] to good [[food]] and if we eat something delicious, we are [[greedy]] for more. | |

| − | |||

| + | If we [[suffer]] from low [[self-esteem]], we may [[feel]] that we do not deserve to be [[happy]] or that we are not worthy enough to receive {{Wiki|affection}} or anything nice from others. Even if others give us something of good [[quality]], we | ||

| − | + | may [[feel]] that they lack {{Wiki|sincere}} [[feelings]] and are only patronizing us. Alternatively, we may [[emotionally]] anesthetize ourselves so that unless the [[sense]] [[experience]] is extreme, we do not [[feel]] anything. In extreme cases, we may even [[feel]] that if we were to enjoy something nice, it might be taken from us - like a bone from a {{Wiki|dog}} - and we might be punished. | |

| + | If we are [[Buddhas]], however, we are able to enjoy everything without such [[confusion]]. In [[tantra]], then, with the high [[self-esteem]] and [[dignity]] of a [[Buddha-figure]], we [[imagine]] that we are able to enjoy things purely. We do this, for example, when we receive the [[offerings]] we make to ourselves in the [[tantric rituals]] (bdag-bskyed mchod-pa) - a practice unique to the [[Gelug tradition]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | All [[Tibetan traditions]] of [[tantra]] include, however, making [[offerings]] to the [[Buddhas]] and to all [[limited beings]]. When doing so, we [[imagine]] that we are able to bring them [[purified]] [[happiness]], without us [[feeling]] any [[confusion]] | ||

| − | + | about that. Often, when we give something to others, we [[feel]] that what we gave was inadequate and that they did not really enjoy it. Our negative attitudes reinforce our low [[self-esteem]] and, afterwards, we may even [[regret]] our gifts. In [[tantra]], on the other hand, we [[imagine]] giving the best things possible and we [[feel]] that they bring [[purified]] [[pleasure]] to their recipients. This reinforces the positive {{Wiki|self-image}} and high [[self-esteem]] of | |

| − | |||

| + | being a [[Buddha-figure]], able to fulfill everybody's wishes for [[happiness]]. To counter [[stinginess]], we [[imagine]] that we have an [[infinite]] supply of [[offerings]] that will never run out. After making [[offerings]], we rejoice and [[feel]] [[happy]] about our giving, without any [[confusion]] or [[doubts]]. Whether making [[offerings]] to the [[Buddhas]], to all [[limited beings]], or to ourselves, we need to understand the [[voidness]] of everything and everyone involved. In other words, we understand that the giver, the recipients, the [[objects]] enjoyed, the acts of enjoying them, and the [[happiness]] felt are devoid of [[existing]] in impossible ways. Thus, we do not inflate or "make a big deal" about our [[own]] or others' [[happiness]]. We do not [[experience]] it in [[dualistic]] manners; nor do we | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==[[Purified]] Environments - [[Mandalas]]== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[cling]] to it. Such practice trains us to focus on [[voidness]] with a [[blissful awareness]], without having the [[happiness]] that we [[experience]] be out of [[harmony]] with our [[understanding]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==[[Purified]] [[Actions]]== | |

| − | + | We also [[imagine]] that we are able to act as [[Buddhas]] do. [[Buddhas]] act by exerting an [[enlightening]] influence (' phrin-las, [[Buddha-activity]]) on others. This requires no [[conscious]] [[effort]] on their parts. By the very way [[Buddhas]] are, they spontaneously accomplish all aims ([[lhun-grub]]), in the [[sense]] that they inspire ([[byin-rlabs]], bless) everyone receptive to their help. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | 1. | + | This works in a manner similar to {{Wiki|charisma}}. |

| − | With our speech, we recite aloud a specific mantra for each action. The mantra is | + | |

| − | usually a Sanskrit phrase or sentence, with special syllables added at the beginning and | + | ==[[Buddhas]] exert four general types of [[enlightening]] influence:== |

| − | end, such as om for body, ah for speech, and hum for mind. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | 1. [[calming]] and quieting others around them (zhi, pacification); stimulating others to grow, to have clearer [[minds]], warmer hearts, be more engaged in positive [[activities]], and so on ([[rgyas]], increase); | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2. bringing others under their power to go in a positive [[direction]] and helping others to unify and gain power from their [[own]] internal forces, also to go in a positive [[direction]] ([[dbang]], power); | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3. stopping [[dangerous]] situations in which others may {{Wiki|hurt}} themselves or be {{Wiki|hurt}} by others (drag-pa, [[wrathful]]). The forceful ([[wrathful]]) [[Buddha-figures]], surrounded by flames, represent this last type of [[enlightening]] influence. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 4. While [[visualizing]] ourselves with the [[bodies]] of [[Buddha-figures]], in the [[purified]] environments of [[mandala]] {{Wiki|palaces}}, and repeating [[mantras]], we [[imagine]] emitting [[rays of light]] and tiny figures, influencing others in the [[four ways]]. We do this while [[understanding]] the [[voidness]] of us, those we influence, our acts of influencing them, and the influence we exert. None of them [[exists]] in impossible ways. Thus, we counter the low [[self-esteem]] of [[feeling]] inadequate and powerless, while not inflating our [[egos]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==[[Mudras]], [[Mantras]], and [[Samadhis]]== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Each [[Buddha-figure]] represents the [[body]], {{Wiki|speech}}, and [[mind of a Buddha]] and the {{Wiki|inseparability}} of the three. Therefore, when [[visualizing]] ourselves performing [[actions]] as [[Buddha-figures]], such as making [[offerings]], we simultaneously do something [[physical]], [[verbal]], and [[mental]] with our ordinary [[bodies]] to integrate the three. | ||

| + | |||

| + | With our [[bodies]], we make a specific [[mudra]] ([[phyag-rgya]]) for each [[action]]. A [[mudra]] is a hand-gesture, often with a complex arrangement of intertwined fingers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 1. With our {{Wiki|speech}}, we recite aloud a specific [[mantra]] for each [[action]]. The [[mantra]] is usually a [[Sanskrit]] [[phrase]] or sentence, with special {{Wiki|syllables}} added at the beginning and end, such as om for [[body]], [[ah]] for {{Wiki|speech}}, and [[hum]] for [[mind]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 2. With our [[minds]], we focus in a specific [[samadhi]] ([[ting-nge-'dzin]]) for each [[action]]. A [[samadhi]] is a [[state]] of total [[absorption]], with [[full concentration]] on an [[object]] or on a [[state of mind]]. The [[action]] may entail [[samadhi]] | ||

| − | + | 3. • on a [[visualization]], such as [[offering]] [[flowers]], on what the [[visualization]] represents, such as [[flowers]] represent [[offering]] our [[knowledge]] to [[benefit]] others, or | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | • on an [[understanding]], such as the inexhaustibility of the [[objects]] we offer or on their [[voidness]]. | |

| − | • on | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

• | • | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==[[Purified]] Manner of [[Enjoyment]]== | |

| + | |||

| + | ==Validity of the Method== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | We may ask the question, "Isn't it a lie or distorted [[cognition]] (log-shes) to think we are [[Buddhas]], when in [[truth]] we are not?" This is not self-deception, however, because all [[beings]] have the complete set of factors within that allow them to become [[Buddhas]]; in other words, everyone has [[Buddha-nature]]. We all have the same [[reality of mind]], | ||

| + | |||

| + | as well as the [[mental activity]] of simultaneously producing and perceiving [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] [[appearances]] (gsal-rig, clarity and [[awareness]]). We all have a certain amount of positive force and [[deep awareness]], which, if properly dedicated, will allow us to overcome limitations and realize our potentials to become [[Buddhas]] and be able to [[benefit]] others most effectively. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Therefore, as [[tantric practitioners]], we think "I am a [[Buddha]]" only within the context of being fully {{Wiki|aware}} that we are not yet [[enlightened]]. We do not pretentiously think that right now we omnisciently know the most [[skillful]] advice to give each being in the [[universe]] to help overcome his or her specific difficulty of the [[moment]]. Rather, we are labeling "me" as a [[Buddha]] on the {{Wiki|future}} continuities of our [[mental]] continuums. | ||

| + | |||

| + | More fully, as properly qualified practitioners of [[tantra]], we necessarily already have accurate [[understanding]] of (1) what is [[enlightenment]], (2) what are the [[Buddha-nature]] factors allowing it, and (3) how these factors, [[enlightenment]], and we [[exist]]; | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | • firm conviction that we have the complete factors of [[Buddha-nature]] within us now; firm conviction, based on accurate [[understanding]] of the [[four noble truths]] and [[voidness]], that not only is [[enlightenment]] possible, but also that our [[own]] [[enlightenment]] is possible; • accurate [[understanding]] of and firm conviction in the complete [[methods]] | |

| + | in [[tantra]] for achieving that [[enlightenment]]; • unshakable [[bodhichitta]] [[motivation]] and resolve to [[benefit]] all [[beings]] as much as is possible and, to be able to do that, to achieve [[enlightenment]] through those [[methods]]; • our [[Buddha-nature]] factors activated by having properly received a [[tantric empowerment]] from a qualified [[tantric master]]; • a healthy [[relation]] with that [[tantric master]], as a source of steady inspiration and reliable guidance to follow the [[tantra path]] correctly; • firm resolve to keep as purely as possible the [[vows]] we have taken at the [[empowerment]]. • | ||

| − | + | If we are missing any of these indispensable prerequisites, our [[tantric practice]] of [[Wikipedia:Imagination|imagining]] ourselves as [[Buddha-figures]] is not only distorted; it may also be {{Wiki|psychologically}} and [[spiritually]] [[dangerous]]. If, however, we have the complete set of prerequisite [[states of mind]], then based on the {{Wiki|future}} continuities of our [[Buddha-nature]] | |

| − | |||

| − | have the complete set of | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | factors developing into those of [[enlightened beings]], we can validly label ourselves now as [[Buddhas]]. Thus, we are using [[mental]] labeling as a method to reach [[enlightenment]], without fooling ourselves that we have already achieved it. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Multiple Limbs and Faces== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Some [[people]] find difficulty in relating to the multiple arms, faces, and {{Wiki|legs}} that the various [[Buddha-figures]] have. These features, however, possess many levels of {{Wiki|purpose}}, meaning, and [[symbolism]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Validity of the Method== | |

| − | + | If, for instance, we try to be {{Wiki|aware}} of twenty-four things abstractly at the same time, we may find this [[achievement]] quite difficult. If, however, we [[imagine]] we have twenty-four arms, each of which represents one of the items, the graphic picture enables us to be more easily {{Wiki|aware}} of the twenty-four simultaneously. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Moreover, since the arms, faces, and {{Wiki|legs}} have many levels of [[symbolism]], not just one, the process of [[Wikipedia:Imagination|imagining]] that we are multifaced, multilimbed [[Buddha-figures]] is like opening up the lenses of our [[minds]]. By helping us to be {{Wiki|aware}} of many things simultaneously, it acts as a [[cause]] for developing the [[omniscient]] all-loving [[awareness]] (rnam-mkhyen) of a [[Buddha]]. | ||

| − | |||

| + | ==(2) Closer Union of Method and [[Wisdom]]== | ||

| − | + | ==In [[Sutra]]== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | On the [[sutra]] level, method is [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[bodhichitta]] and [[wisdom]] is the discriminating [[awareness]] of [[voidness]]. These are the foundations for strengthening and expanding the enlightenment-building networks of positive force and [[deep awareness]], the obtaining [[causes]] for achieving the [[body]] and [[mind of a Buddha]]. | ||

| − | ( | + | [[Conventional]] [[bodhichitta]] focuses on our {{Wiki|future}} [[enlightenment]] with two accompanying {{Wiki|intentions}} (' [[dun-pa]]): to achieve that [[enlightenment]] and to [[benefit]] all [[beings]] by means of that. Discriminating [[awareness]] of [[voidness]] focuses on an [[absolute absence]] ([[med-dgag]], [[nonimplicative negation]]) of [[true existence]], with the [[understanding]] that |

| − | + | there is no such manner of [[existence]]. Nothing has its [[existence]] and [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] established by the power of some defining [[characteristic]] marks inherently findable within it. Thus, in [[sutra]], the main [[causes]] for a | |

| + | [[body]] and a [[mind of a Buddha]] have different ways of cognitively taking their [[objects]] (' dzin-stangs). On the most basic level, one is with the wish to attain something; the other is with the [[understanding]] that there are no such things as certain impossible modes of [[existence]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [For a more advanced [[discussion]], see: Relationships with [[Objects]] {3}.] A [[moment]] of [[cognition]] cannot have two different manners of cognitively taking an [[object]]. Because of that, [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[bodhichitta]] and the discriminating [[awareness]] of [[voidness]] cannot occur simultaneously in one [[moment]] of [[cognition]]. We can only practice the two within the context of each other. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | other | ||

| − | |||

| + | Practicing [[cognition]] "A" within the context of [[cognition]] "B" means to generate "B" during the [[moment]] immediately preceding "A." The momentum or legacy ([[sa-bon]], seed) of "B" continues during "A," although "B" itself no longer occurs. In a [[sense]], the momentum of "B" [[flavors]] "A," without "A" and "B" occurring simultaneously. This is the way [[sutra]] practice combines [[method and wisdom]]. | ||

| − | [For a more advanced discussion, see: | + | [For a more advanced [[discussion]], see: The Union of Method and [[Wisdom]] in [[Sutra]] and [[Tantra]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [ | + | ==[[Gelug]] and Non-Gelug Presentations== |

| + | ==Buddha-Figures as Method in General [[Tantra]]== | ||

| − | |||

| − | Buddha- | + | The [[enlightening]] [[body]] and [[mind of a Buddha]] share the same [[essential nature]] ([[ngo-bo gcig]], one by [[nature]]), in the [[sense]] that they are two facts about the same [[phenomenon]]. As two facts about a [[Buddha]], both are simultaneously the case in each [[moment]] of a [[Buddha's]] [[experience]]. |

| − | + | ==Multiple Limbs and Faces== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In a colloquial manner of {{Wiki|speaking}}, they "come together in one package." Moreover, a [[Buddha's]] [[mind and body]] are [[inseparable]] ([[dbyer-med]]) from each other. In other words, the two occur simultaneously in each [[moment]], in the [[sense]] that if one is the case, so is the other. The [[body]] of a [[Buddha]] cannot be {{Wiki|present}} without the [[mind]] of that [[Buddha]], and [[vice versa]]. | |

| + | [For a more advanced [[discussion]], see: Relationships between Two [[Objects]] in General {2} {5}.] | ||

| − | + | The most efficient means for achieving the simultaneous occurrence of an [[enlightening]] [[body]] and [[mind]] is to practice in one [[moment]] of [[cognition]] the [[causes]] for both. [[To accomplish]] this aim, [[tantra]] takes as method not only [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[bodhichitta]], but also having the [[body]] of a [[Buddha-figure]]. To have such an [[enlightening]] [[body]] is the | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [ | + | actual method, motivated by [[bodhichitta]] and dedicated to [[enlightenment]], that will enable us to [[benefit]] all others. We cannot [[benefit]] everyone as fully as a [[Buddha]] does with our ordinary [[bodies]], which are limited in {{Wiki|innumerable}} ways. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Correspondingly, [[wisdom]] in [[tantra]] is the discriminating [[awareness]] of the [[voidness]] of ourselves in terms of being [[Buddha-figures]], and not simply the [[voidness]] of ourselves in terms of the [[aggregate]] factors (Skt. [[skandha]]) that constitute our ordinary [[bodies]] and [[minds]]. [[Voidness]] and the Basis for a [[Voidness]] | ||

| − | + | [[Voidness]] is an [[absolute absence]] of [[true existence]]. It is the deepest [[truth]] about how something [[exists]]. As an [[unchanging]] fact about something, the [[voidness]] of something cannot [[exist]] {{Wiki|independently}} by itself; it must always have a basis - that "something." In other words, the basis for a [[voidness]] ([[stong-gzhi]]) is the specific [[object]] that is devoid of [[existing]] in impossible ways. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Note that because each basis for a [[voidness]] is {{Wiki|individual}}, the [[voidness]] of each basis is likewise {{Wiki|individual}}. Associated with each basis, then, is an {{Wiki|individual}} instance of a [[voidness]]. All [[voidnesses]] are equally [[voidnesses]], but the [[voidness]] of one basis is not the [[voidness]] of another basis. This resembles the fact that all noses are | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | basis | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | equally noses, but my {{Wiki|nose}} is not your {{Wiki|nose}}. Moreover, any basis for a [[voidness]] must also have aspects ([[rnam-pa]]), one of which a [[mind]] makes [[appearances]] of when it [[Wikipedia:Cognition|cognizes]] the basis. If the [[object]] is [[physical]], for instance, the aspect may be its [[form]], [[sound]], {{Wiki|smell}}, {{Wiki|taste}}, or [[physical]] [[sensation]]. If the [[object]] is a way of being {{Wiki|aware}} of something, for instance [[love]], the [[appearance]] of it in a [[cognition]] may be the [[emotional]] [[feeling]] of it that arises. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Moreover, any basis for a voidness must also have aspects (rnam-pa), one of which a mind | ||

| − | makes appearances of when it cognizes the basis. If the object is physical, for instance, the | ||

| − | aspect may be its form, sound, smell, taste, or physical sensation. If the object is a way of | ||

| − | being aware of something, for instance love, the appearance of it in a cognition may be the | ||

| − | emotional feeling of it that arises. | ||

| − | Two Truths | + | ==[[Two Truths]]== |

| − | The appearance of the basis for a voidness and its actual voidness are two inseparable facts | + | The [[appearance]] of the basis for a [[voidness]] and its actual [[voidness]] are two [[inseparable]] facts about the same [[object]]. They are called the [[two truths]] ([[bden-gnyis]], [[two levels of truth]]) about an [[object]]. Both are true and are inseparably the case, regardless of whether one [[moment]] of [[mind]] [[perceives]] them simultaneously. |

| − | about the same object. They are called the two truths (bden-gnyis, two levels of truth) about | ||

| − | an object. Both are true and are inseparably the case, regardless of whether one moment of | ||

| − | mind perceives them simultaneously. | ||

| − | The superficial truth (kun-rdzob bden-pa, relative truth) about something is how it | + | The [[superficial]] [[truth]] ([[kun-rdzob bden-pa]], [[relative truth]]) about something is how it appears, namely |

| − | appears, namely | ||

1. | 1. | ||

| − | Buddha-Figures as Method in General Tantra | + | ==Buddha-Figures as Method in General [[Tantra]]== |

• what it appears to be, | • what it appears to be, | ||

| − | • how it appears to exist. | + | • how it appears to [[exist]]. |

| − | The deepest truth (don-dam bden-pa, ultimate truth) about the same phenomenon is | + | The deepest [[truth]] ([[don-dam bden-pa]], [[ultimate truth]]) about the same [[phenomenon]] is how it actually [[exists]]. |

| − | how it actually exists. | ||

| − | 2. | + | 2. General [[tantra]] takes as [[method and wisdom]] the [[two truths]] about ourselves as [[Buddha-figures]] - the [[appearance]] of the [[Buddha-figure]] as a basis for [[voidness]] and its actual [[voidness]]. |

| − | General tantra takes as method and wisdom the two truths about ourselves as Buddha-figures - | ||

| − | the appearance of the Buddha-figure as a basis for voidness and its actual voidness. | ||

| − | Method and Wisdom in General Tantra Having One Manner of Cognitively | + | Method and [[Wisdom]] in General [[Tantra]] Having One Manner of Cognitively |

| − | Taking an Object | + | ==Taking an [[Object]]== |

| − | Conceptual and nonconceptual cognitions of voidness entail two phases, both of which occur | + | {{Wiki|Conceptual}} and [[nonconceptual]] [[cognitions]] of [[voidness]] entail two phases, both of which occur during a [[meditation]] session on [[voidness]]: |

| − | during a meditation session on voidness: | ||

| − | total absorption (mnyam-bzhag, meditative equipoise) cognition of voidness that is like | + | total [[absorption]] ([[mnyam-bzhag]], [[meditative equipoise]]) [[cognition]] of [[voidness]] that is like [[space]], |

| − | space, | ||

| − | 1. | + | 1. subsequent [[attainment]] (rjes-thob, [[post-meditation]], subsequent [[realization]]) [[cognition]] of [[voidness]] that is [[like an illusion]]. |

| − | subsequent attainment (rjes-thob, post-meditation, subsequent realization) cognition of | + | |

| − | voidness that is like an illusion. | + | 2. The focal [[object]] ([[dmigs-yul]]) during the total [[absorption]] phase is the deepest [[truth]] about something, its [[voidness]]. The [[superficial]] [[truths]] about it do not appear at that time. During the subsequent [[attainment]] phase, the focal [[object]] is the [[superficial]] [[truth]] about the [[object]], while its deepest [[truth]] does not appear. The presence of |

| + | |||

| + | an [[appearance]] of [[true existence]] and the [[absolute absence]] of [[true existence]] cannot appear simultaneously in one [[moment]] of [[cognition]], whether {{Wiki|conceptual}} or [[nonconceptual]]. They are mutually exclusive. Nevertheless, the [[two truths]] remain [[inseparable]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The situation resembles sitting on the ground floor of a house and [[seeing]] through the window a [[person]] walk {{Wiki|past}}. Although only the top half of the [[person]] appears to go by, this does not mean that the [[person]] is missing a bottom half. The limitation derives from the side of the {{Wiki|perspective}}, not from the side of the [[person]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Thus, although the [[appearance]] of a [[Buddha-figure]] and its [[voidness]], as [[method and wisdom]], remain always [[inseparable]], total [[absorption]] [[cognition]] of [[voidness]] focuses only on [[wisdom]]. Subsequent [[attainment]] [[cognition]] of [[voidness]] focuses only on method. | ||

| − | + | As in the case with [[bodhichitta]], [[cognition]] of [[wisdom]] can only be held by the force of an immediately preceding [[moment]] of [[cognition]] of method, and [[vice versa]]. [[Wisdom]] and method are not simultaneous. Nevertheless, [[cognition]] of the [[appearance]] of a [[Buddha-figure]] as method still avoids the shortcoming of [[bodhichitta]]. This is because the | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | manners with which [[wisdom]] and method cognitively take their [[objects]] during the total [[absorption]] and subsequent [[attainment]] phases are not mutually exclusive. Rather, they are {{Wiki|equivalent}} manners. Both are ways of cognitively taking [[voidness]] as an [[object]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | More specifically, the manners with which [[wisdom]] and method cognitively take an [[object]] here are two facts about or ways of describing the same [[phenomenon]] - a manner of cognitively taking an [[object]] - that can be [[logically]] isolated from each other and conceptually specified as two different conceptually isolated items ([[ngo-bo gcig]] [[ldog-pa tha-dad]]). The two {{Wiki|equivalent}} manners of cognitively taking an [[object]] are with the discriminating [[awareness]] that | |

| − | |||

| − | are | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==[[Two Truths]]== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | 1. there is no such thing as [[true existence]]; | |

| + | 2. the [[appearance]] of what resembles [[true existence]] does not correspond to anything real. It is in this fashion, then, that general [[tantra practices]] [[method and wisdom]] with one manner of cognitively taking an [[object]], and thus achieves a closer union of the two than [[sutra]] practice does. | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Summary== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | • All bases for [[voidness]] are [[inseparable]] from their [[voidness]]. | |

| + | • Their [[appearance]] and [[voidness]] are two [[inseparable]] [[truths]] about them. | ||

| − | + | Although focus on both can only alternate, still the manners of cognitively taking them during total [[absorption]] and subsequent [[attainment]] are not [[contradictory]]: they are {{Wiki|equivalent}} to each other. | |

| − | • | + | • Although these points are valid for all [[phenomena]]; nevertheless, focusing on a table or on our ordinary [[bodies]] as bases for [[voidness]] cannot serve as a [[union of method and wisdom]]. We can only help others in the [[enlightening]] manner of a [[Buddha]] with the [[body]] of a [[Buddha-figure]]. Moreover, focusing on [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] [[bodhichitta]] and its [[voidness]] will also not serve as a [[union of method and wisdom]], because the two still have [[contradictory]] manners of cognitively taking their [[objects]]. |

| − | + | Even if we are not yet able to focus on our [[appearances]] as [[Buddha-figures]] and on their [[voidness]] with one manner of cognitively taking an [[object]], still we have [[bodies]] while we are focusing on their [[voidness]]. When [[tantra]] commentaries [[state]] that the [[mind]] [[understanding]] [[voidness]] appears as a [[Buddha-figure]], this not only means that the | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[mind]] [[Wikipedia:Cognition|cognizing]] [[voidness]] gives rise to an [[appearance]] of a [[Buddha-figure]] as the basis for that [[voidness]], while maintaining an [[understanding]] of its [[voidness]]. It also means, on a simpler level, that the [[body]] of the [[person]] focusing on [[voidness]] appears as a [[Buddha-figure]], whether or not the [[person]] [[Wikipedia:Cognition|cognizes]] it at that [[moment]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | For a more advanced [[discussion]], see: The Union of Method and [[Wisdom]] in [[Sutra]] and [[Tantra]]: | ||

| − | |||

| + | ==[[Gelug]] and Non-Gelug Presentations== | ||

| − | + | ==(3) Special Basis for [[Voidness]]== | |

| − | |||

| − | The next reason why tantra is faster than sutra is that the basis for voidness it uses is special. It | + | The next [[reason]] why [[tantra]] is faster than [[sutra]] is that the basis for [[voidness]] it uses is special. It takes, as the basis for [[voidness]] [[meditation]], the [[appearance]] of the [[body]] of a [[Buddha-figure]]. Such a basis is special from three points of view. |

| − | takes, as the basis for voidness meditation, the appearance of the body of a Buddha-figure. | ||

| − | Such a basis is special from three points of view. | ||

| − | Compared to most other objects, the appearances of Buddha-figures are: | + | Compared to most other [[objects]], the [[appearances]] of [[Buddha-figures]] are: |

• less deceptive, | • less deceptive, | ||

| − | • more stable, | + | • more {{Wiki|stable}}, |

| + | |||

| + | • more {{Wiki|subtle}}. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Buddha-Figures as Less Deceptive== | ||

| + | |||

| − | + | In [[sutra]], we focus on the [[voidness]] of a [[phenomenon]] or of a [[person]]. When we think of the basis for that [[voidness]], for instance, our ordinary [[bodies]], the [[appearances]] of the bases that arise in our [[cognitions]] - both {{Wiki|conceptual}} and [[nonconceptual]] - are produced by [[minds]] that are | |

| + | Method and [[Wisdom]] in General [[Tantra]] Having One Manner of CognitivelyTaking an Object40 affected by [[causes]] for deceptive (' khrul-snang) or discordant appearance-making ([[gnyis-snang]], dual [[appearances]]). In other words, our usual [[minds]] make our [[bodies]] appear to us as [[existing]] in deceptive manners discordant with their deepest [[truth]]. | ||

| − | + | For instance, our [[minds]] make them appear truly and inherently to [[exist]] as fat, ugly, and unlovable. Because of believing that this deceptive manner of [[existence]] corresponds to [[reality]], we may [[feel]] alienation from our [[bodies]] and self-hatred toward them. | |

| − | In | + | In [[voidness]] [[meditation]], we think how our [[bodies]] do not actually [[exist]] in the impossible manners in which they appear to us to [[exist]]. It may be an accurate [[superficial]] [[truth]] that presently we are fat and ugly by the [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] standards of our {{Wiki|societies}} and that no one loves us by our personal conventions of what [[love]] means. Nevertheless, we do not truly and inherently [[exist]] in those ways, forever, regardless of circumstances and points of view. That is impossible. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | While focusing on the [[voidness]] of our ordinary [[bodies]] - the [[absolute absence]] of their [[existing]] in impossible manners - [[disturbing emotions]] and attitudes ([[nyon-mongs]], Skt. [[klesha]], [[afflictive emotions]]) cannot affect our [[minds]]. Nevertheless, the bases for that [[voidness]], our ordinary [[bodies]], are [[objects]] that our [[minds]] made appear in | |

| − | |||

| − | ( | ||

| − | |||

| − | minds | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | deceptive ways before our total [[absorption]] on their [[voidness]]. Because of that, our previous [[experiences]] of deceptive appearance-making and [[disturbing emotions]] can, in a [[sense]], infect or destabilize our understandings of that [[voidness]]. The {{Wiki|mechanism}} is similar to that by which focus on [[voidness]] can be within the context of the legacies of previous moments of [[bodhichitta]]. | ||

| − | In | + | In [[tantra]], on the other hand, we first dissolve all ordinary [[appearances]]. We halt our [[minds]]' deceptive appearance-making by starting with the [[understanding]] of [[voidness]]. Then, within that [[state]] of an [[absolute absence]], we [[imagine]] that we arise in the [[forms]] of [[Buddha-figures]] and focus on the [[voidness]] of those [[forms]]. Thus, the situation differs significantly from [[meditating]] on the [[voidness]] of our ordinary [[bodies]]. In [[tantra]], we already understand [[voidness]] and then within the context of [[voidness]], we focus on the [[bodies]] of [[Buddha-figures]] - things that we have already understood are devoid of [[true existence]]. In this way, the [[appearances]] of ourselves as [[Buddha-figures]] are not as deceptive as the [[forms]] of our ordinary [[bodies]] would be. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In short, normally when we think of the [[forms]] of our ordinary [[bodies]], we [[emotionally]] overreact to them as "me" in terms of {{Wiki|disturbing}} [[feelings]] and judgments, such as "My [[body]] is ugly, I don't like it," or "How beautiful I am." Such {{Wiki|disturbing}} [[feelings]] can undermine our understandings of their [[voidness]]. Focusing on the [[voidness]] of the [[purified]] [[forms]] of [[Buddha-figure]] [[bodies]] avoids this [[danger]] and disadvantage. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | voidness. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Buddha-Figures as More {{Wiki|Stable}}== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Buddha- | ||

| − | + | When we focus on the [[voidness]] of our ordinary [[bodies]] in [[bodhisattva]] [[sutra]], the bases for that [[voidness]] are capricious (fleeting) [[objects]]. They are [[bodies]] that sometimes [[feel]] good, sometimes {{Wiki|hurt}}, and so on. [[Subject]] to the unpredictable {{Wiki|impulses}} of [[karma]], they are unstable and noticeably change each time we [[meditate]]. They even change during the course of one session - for instance, as our knees begin to ache. | |

| + | In contrast, each time we try to focus on the [[voidness]] of the [[body]] of a [[Buddha-figure]], its [[appearance]] as the basis for that [[voidness]] does not grossly change. The [[body]] that appears can perform functions such as helping | ||

| − | + | others - even if only in our [[imaginations]] - and in this [[sense]] is a nonstatic ([[impermanent]]) [[phenomenon]]. However, it is a so-called "static" nonstatic [[phenomenon]] ([[rtag-pa]] shes-bya-ba'i [[mi-rtag-pa]]), in the [[sense]] that it does not grow old, does | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Buddha-Figures as Less Deceptive== | ||

| − | |||

| + | not become tired, does not fall ill, and so on. It always remains in the same [[condition]] whenever we focus on it in [[meditation]]. Thus, [[Buddha-figures]] serve as more {{Wiki|stable}} [[objects]] than our capricious [[bodies]] do for gaining and enhancing the [[understanding]] of [[voidness]] and for maintaining single-minded [[concentration]] on that [[voidness]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Buddha-Figures as More {{Wiki|Subtle}}== | ||

| − | |||

| + | Our ordinary [[bodies]] as bases for [[voidness]] are gross [[forms]] that appear to our [[eye consciousness]]. Because they are gross, they appear to us as concrete and solid [[objects]], [[existing]] {{Wiki|independently}} of a relationship with the [[mind]]. That relationship is as what the [[mental]] labels or [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] for them refer to. The [[truth]] that they are devoid of [[existing]] in such impossible manners is not so obvious. | ||

| − | + | In general [[tantra]], however, the [[bodies]] of the [[Buddha-figures]] on which we focus are {{Wiki|subtle}} [[forms]] that we see only in our [[minds]]' [[eyes]]. Because of their subtlety, it is more obvious that they lack [[existence]] {{Wiki|independent}} of what a [[mind]] can impute. Thus, it is easier to understand their [[voidness]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==(4) Special Level of [[Mental Activity]]== | ||

| − | |||

| + | [[Wikipedia:Anuttarayoga tantra|Anuttarayoga tantra]] analyzes three levels of [[mental activity]] ([[mind]]): gross, {{Wiki|subtle}}, and subtlest. The gross level involves the five types of [[sense consciousness]] - namely [[eye]], {{Wiki|ear}}, {{Wiki|nose}}, {{Wiki|tongue}}, and [[body consciousness]]. It is always [[nonconceptual]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | 1. | + | ==1. 2. The {{Wiki|subtle}} level concerns [[mind consciousness]], both {{Wiki|conceptual}} and [[nonconceptual]]==. |

| − | 2. The subtle level concerns mind consciousness, both conceptual and nonconceptual. | + | |

| + | |||

| + | The subtlest level of [[mind]] is called "[[clear light]]" (' [[od-gsal]]). It is like a laser beam of [[mental activity]]. It refers to the basic [[activity]] of merely producing and perceiving [[Wikipedia:cognition|cognitive]] [[appearances]], simultaneously, which provides continuity of [[experience]] from [[moment]] to [[moment]] and from one [[lifetime]] to the next, even into [[enlightenment]]. Clear-light [[mental activity]] is exclusively [[nonconceptual]]. Only the [[methods]] of [[anuttarayoga]] bring access to this level of [[mind]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | 3. In [[sutra]] and the three [[lower classes of tantra]], [[nonconceptual cognition of voidness]] is by valid [[yogic]] [[cognition]] ([[rnal-'byor]] [[mngon-sum]]), which is on the second of the three levels of [[mental activity]], the {{Wiki|subtle}} one. Unlike our usual [[mental]] [[cognition]], which arises from the dominating [[condition]] ([[bdag-rkyen]]) of our [[mental]] sensors | ||

| + | |||

| + | (yid-kyi [[dbang-po]]), [[yogic]] [[cognition]] arises from a [[state]] of combined [[shamatha]] ([[zhi-gnas]]; [[calm abiding]], [[mental]] quiescence) and [[vipashyana]] ([[lhag-mthong]], [[special insight]]) as its dominating [[condition]]. [[Shamatha]] is a serenely stilled and settled [[state of mind]], while [[vipashyana]] is an exceptionally perceptive [[state]]. Because {{Wiki|conceptual}} [[cognition]] is exclusively with the {{Wiki|subtle}} level of [[mental activity]] and [[clear light]] [[cognition]] is exclusively [[nonconceptual]], | ||

| + | |||

| + | • {{Wiki|conceptual}} [[cognition]] of [[voidness]] is exclusively with the [[subtle level of mind]]; [[nonconceptual cognition of voidness]] may be with either the {{Wiki|subtle}} or the subtlest level of [[mind]]. | ||

| − | + | • Therefore, [[tantra practice]] in general includes, in its [[highest]] class, using a special level of [[mental activity]] for nonconceptually [[Wikipedia:Cognition|cognizing]] [[voidness]] - [[clear-light mind]] - although not all classes of [[tantra]] use this level. | |

| − | mental activity | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Buddha-Figures as More {{Wiki|Stable}}== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Concluding Points Concerning [[Voidness]] in [[Sutra]] and [[Tantra]]== | ||

| − | |||

| + | {{Wiki|Subtle}} and subtlest [[mental activity]] nonconceptually {{Wiki|cognize}} the same [[voidness]], namely [[voidness]] as an [[absolute absence]] of [[true existence]]. [[Gelug]] is unique in asserting that {{Wiki|conceptual}} and [[nonconceptual cognition of voidness]] also {{Wiki|cognize}} this same [[voidness]]. Because of this, both stages of practice in each of the four [[tantra]] classes - | ||

| − | + | the [[yoga]] [[with signs]] (mtshan-bcas-kyi rnal-' byor) and the [[yoga without signs]] (mtshan-med-kyi [[rnal-'byor]]) in the first [[three classes]], and the [[generation stage]] ([[bskyed-rim]], [[development stage]]) and [[complete stage]] ([[rdzogs-rim]], [[completion stage]]) in [[anuttarayoga]] - have the same [[understanding]] of [[voidness]]. | |

| − | + | {{R}} | |

| − | + | [[Category:Buddhist Terms]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Buddhism]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Tibetan Buddhism]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Tantras]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Vajrayana]] | |

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 04:05, 30 September 2021

Gelug Presentation of Tantra in General

Methodology

Tantra is well known as being a quicker and more efficient method for achieving enlightenment than is sutra. To appreciate tantra and put full enthusiasm into its practice in a realistic manner, it is important to know what makes tantra so special. We can discuss this on several levels, depending on the tantra class and specific tantra. Here, however, let us speak of only three levels:

1. tantra in general - common to all four tantra classes, anuttarayoga tantra in general - common to the main anuttarayoga tantras, such as Guhyasamaja,

3. Kalachakra tantra.

On each level, we shall analyze four reasons for its enhanced speed:

1. There are closer analogies within the practice.

2. There is a closer union of method and wisdom.

3. There is a special basis for voidness used for gaining the understanding of voidness.

4. There is a special level of mental activity used for perceiving voidness.

We shall use as our basis the Gelug presentation of the subject matter, as found in A Grand Presentation of the Stages of Hidden Mantra (sNgags-rim chen-mo) by the fourteenth-century master Tsongkhapa (Tsong-kha-pa Blo-bzang grags-pa). The four-point analysis has been extrapolated from salient points in this text, although Tsongkhapa himself has not structured his discussion in this manner. As a supplement, we shall indicate the features unique to the explanations given in the non-Gelug systems - Sakya, Kagyu, and Nyingma - when they significantly differ.

(1) Closer Analogies

The practices of both bodhisattva sutra and general tantra act as causes for reaching the goal of enlightenment, with the attainment of the physical corpuses (Skt. rupakaya, form bodies) and omniscient all-loving mental activity (Skt. dharmakaya) of a Buddha. The causal practices in each, however, resemble the goal to different degrees.

In Sutra

The bodhisattva sutras discuss the two enlightenment-building networks (tshogs-gnyis, the two collections) as causes for achieving a body and mind of a Buddha. These are the networks of positive force (bsod-nams, Skt. punya, merit, positive potential) and deep awareness (ye-shes, Skt. jnana, wisdom, insight). Each is a network in the sense that its constituents connect with and reinforce one another, rather than just accumulate as members of a passive collection.

We build up the two enlightenment-building networks exclusively with a bodhichitta motivation beforehand and a dedication to enlightenment afterward. Otherwise, our constructive (dge-ba, virtuous) actions and meditation on the nature of reality constitute only samsara-building networks of positive force and deep awareness. Such networks serve merely as causes for achieving a body and mind in one of the better rebirth states.

The minimum level of bodhichitta required for our constructive actions and meditation to constitute enlightenment-building networks is a labored (rtsol-bcas) state, reached by relying on a line of reasoning. With the attainment of unlabored (rtsol-med) bodhichitta, which arises without such reliance, we become bodhisattvas.

An extensive enlightenment-building network of positive force serves as the obtaining cause (nyer-len-gyi rgyu) for the body of a Buddha. An obtaining cause is the item from which we obtain the result. It functions as the natal source (rdzas, natal substance) giving rise to the result as its successor. It ceases to exist

simultaneously with the arising of its result. For example, a seed is the obtaining cause for a sprout. Obtaining causes and their results, however, do not need to be forms of physical phenomena. Today's understanding of a Dharma point, for instance, is the obtaining cause that gives rise to tomorrow's understanding of it. Obtaining causes need simultaneously acting conditions (lhan-cig byed-rkyen) in order to give rise to their results. Here,

an enlightenment-building network of positive potential requires as a simultaneously acting condition an enormous enlightenment-building network of deep awareness. Likewise, an extensive enlightenment-building network of deep awareness, as the obtaining cause for the mind of a Buddha, requires a vast enlightenment-building network of

positive force as its simultaneously acting condition. The pair of enlightenment-building networks is required for achieving either of the two, a body or a mind of a Buddha. [For a more advanced discussion, see: Relationships between Two Objects in General {2} {5}.]

Although the sutra-level causes for enlightenment are somewhat like their results, they are not so similar. For instance, a Buddha's physical body has thirty-two major features that are indicative of their causes. A Buddha's long tongue, for example, indicates and represents the type of love with which he or she, in previous lives as a bodhisattva, took care of others like a mother animal licking her young. Working with such causes alone requires three zillion (countless) eons to reach the goal.

General Tantra as the Resultant Vehicle

In general tantra, the obtaining causes for attaining the enlightening body and mind of a Buddha are more analogous to the results we wish to attain. We practice now as if we had already achieved our goals. Because of this feature, tantra, as the "resultant vehicle," is more efficient for reaching enlightenment.

Tantra practice resembles a dress rehearsal. If we wish to dance in a ballet, we need to attend ballet school first and learn to dance. The obtaining cause, however, that functions as the natal source giving rise to the actual performance as its immediate successor, is the dress rehearsal of the ballet. Likewise, if we wish to practice tantra, we need to learn and develop first the essentials from sutra. Subsequent tantra practice is like the dress rehearsal to combine the

In Sutra

essentials to bring us to enlightenment as its immediate successor. In all classes of tantra, then, we simulate four purified factors (rnam-par dag-pa bzhi) we will have as Buddhas. They are purified of all suffering and the causes of suffering, in the sense that they arise in our experience when we have achieved a true stopping (' gog-bden, true cessation) of both. The four are

2. purified environments,

3. purified manners of experiencing sense objects with enjoyment (longs-spyod),

We do this by imagining that we have all four factors now. Using our imaginations (dmigs-pa) in these ways acts as a cause to achieve the four purified factors more quickly. Most translators call this process "visualization." The term, however, is a bit misleading, because the process is not merely visual. It involves the entire scope of our imaginations - imagining sights, sounds, smells, tastes, physical sensations, feelings, emotions, actions, and so on. Tantra harnesses the power of imagination - an extremely potent tool we all possess.

Purified Bodies

In tantra, we imagine that we have purified bodies like those of one of the Buddha-figures - the many forms in which an enlightening body can appear. As the etymology of yi-dam, the Tibetan word for Buddha-figure, implies, we "bond our minds closely" with them in daily practice in order to reach enlightenment. Thus, we imagine our bodies are transparent, made of clear light, and able to multiply into countless replica bodies, all with the infinite energy and capabilities of those of a Buddha.

Moreover, we do not imagine ourselves as Buddha-figures merely during meditation sessions. We try to maintain mindfulness (dran-pa) on this the entire day. Mindfulness is a subsidiary awareness (sems-byung, mental factor) that accompanies cognition of something. Like a "mental glue," it prevents our attention from losing its object.

With mindfulness, we maintain both the clarity (gsal-ba) and self-esteem or dignity (nga-rgyal, pride) of the Buddha-figure. Clarity is the mental activity of producing the cognitive appearance of the Buddha-figure, regardless of level of clarity of detail or focus. Self-esteem is the mental activity of labeling "me" on the continuity of the appearance of the figure and feeling that this is who we actually are.

Tsongkhapa emphasized that maintaining mindfulness on the self-esteem of being the figure is more important at first than trying to gain clarity of detail and maintaining mindfulness on the detail. To begin, we need merely achieve a rough clarity of visualization, to serve as the basis for labeling (gdags-gzhi) "me."

Tantric Transformation of Self-Image

While visualizing ourselves as Buddha-figures, we also imagine that we have the self-images associated with the figures. Many people have negative self-images, for instance as not being good enough or not deserving to be happy or loved. In contrast to such negative self-images,

Buddha-figures imply positive ones.

General Tantra as the Resultant Vehicle

In Buddhism, negative and positive do not denote bad and good. Rather, they imply destructive and constructive. Destructive means ripening into problems and suffering, in this life and future ones, through a process of leaving a legacy (sa-bon, seed, tendency) and habit (bag-chags, instinct) on our mental continuums. Constructive means ripening into happiness through a similar process.

Buddha-figure practice resembles, in a sense, a type of "mental judo" with which we work with the tendencies of our minds to project self-images. Instead of projecting negative ones, we project positive self-images instead. Each Buddha-figure has a positive self-image associated with it. For example, Avalokiteshvara represents being a

warm, loving, and compassionate person; Manjushri (' Jam-dpal dbyangs), being someone clearheaded and able to understand everything. We practice with one or another figure in order to emphasize a specific positive self-image, in accordance with our dispositions and needs.