Difference between revisions of "Buddhism in the West: Self Realization or Self Indulgence?"

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

“I am not [[religious]], but I`m [[spiritual]]”. This is a commonly heard statement, especially among younger [[people]], many of whom are disaffected with organized [[religion]], but seek some [[form]] of {{Wiki|secular}} [[spirituality]]. For many Westerners who would describe themselves in the above way, the [[teaching]] of [[Buddhism]] holds great [[attraction]]. Different from the {{Wiki|Abrahamic}} [[religions]], [[Buddhism]] is not based on a [[revelation]] by [[God]], but takes its starting point from the [[enlightenment]] [[experience]] of [[Shakyamuni]] [[Gautama]], an [[Indian]] {{Wiki|prince}} of the 6th to 5th century BCE, called [[Buddha]], literally “the [[Awakened One]],” by his [[disciples]]. Even though the new {{Wiki|movement}} that he founded developed in [[India]] and in other regions of {{Wiki|Asia}} as a monastic-based institution, [[Buddhist teachers]] coming to the [[West]] established practice centers for lay followers rather than [[monasteries]] for [[celibate]] communities. | “I am not [[religious]], but I`m [[spiritual]]”. This is a commonly heard statement, especially among younger [[people]], many of whom are disaffected with organized [[religion]], but seek some [[form]] of {{Wiki|secular}} [[spirituality]]. For many Westerners who would describe themselves in the above way, the [[teaching]] of [[Buddhism]] holds great [[attraction]]. Different from the {{Wiki|Abrahamic}} [[religions]], [[Buddhism]] is not based on a [[revelation]] by [[God]], but takes its starting point from the [[enlightenment]] [[experience]] of [[Shakyamuni]] [[Gautama]], an [[Indian]] {{Wiki|prince}} of the 6th to 5th century BCE, called [[Buddha]], literally “the [[Awakened One]],” by his [[disciples]]. Even though the new {{Wiki|movement}} that he founded developed in [[India]] and in other regions of {{Wiki|Asia}} as a monastic-based institution, [[Buddhist teachers]] coming to the [[West]] established practice centers for lay followers rather than [[monasteries]] for [[celibate]] communities. | ||

| − | The [[attraction]] to [[spirituality]], however it is understood and practiced, rather than to an organized [[form]] of [[religion]] has to be understood from the context of secularization– one of the long-term effects of the [[enlightenment]] and modernity. With the advent of {{Wiki|modern}} [[thinking]], and also [[scientific]], technological and economic developments, [[religions]] have lost the comprehensive power that they once possessed. Whereas before the [[enlightenment]], [[religion]] was used to explain every aspect of [[life]], this of course is no longer the case, except in the most {{Wiki|fundamentalist}} [[forms]] of [[religion]] that regard modernity as a threat or at least something to be resisted. The violent reactions to the Muhammad-cartoons and the Regensburg [[speech]] of the Pope are recent examples of [[religious]] attitudes judged by many to be backward, {{Wiki|fundamentalist}} and “unenlightened,” which caught the [[attention]] of the media and the [[world]]. For most [[people]] in the [[West]], [[religion]] or [[religious]] [[beliefs]] are no longer something to fight about. They are often not even deemed a good [[subject]] of [[discussion]]. In a {{Wiki|Western culture}}, [[religious]] choices are regarded to be personal ones, and most certainly not something that should be imposed on others. | + | The [[attraction]] to [[spirituality]], however it is understood and practiced, rather than to an organized [[form]] of [[religion]] has to be understood from the context of secularization– one of the long-term effects of the [[enlightenment]] and modernity. With the advent of {{Wiki|modern}} [[thinking]], and also [[scientific]], technological and economic developments, [[religions]] have lost the comprehensive power that they once possessed. Whereas before the [[enlightenment]], [[religion]] was used to explain every aspect of [[life]], this of course is no longer the case, except in the most {{Wiki|fundamentalist}} [[forms]] of [[religion]] that regard modernity as a threat or at least something to be resisted. The [[violent]] reactions to the Muhammad-cartoons and the Regensburg [[speech]] of the Pope are recent examples of [[religious]] attitudes judged by many to be backward, {{Wiki|fundamentalist}} and “unenlightened,” which caught the [[attention]] of the media and the [[world]]. For most [[people]] in the [[West]], [[religion]] or [[religious]] [[beliefs]] are no longer something to fight about. They are often not even deemed a good [[subject]] of [[discussion]]. In a {{Wiki|Western culture}}, [[religious]] choices are regarded to be personal ones, and most certainly not something that should be imposed on others. |

| − | What is the [[Buddhist]] [[attitude]] to [[religious]] [[beliefs]], including [[belief]] in [[God]]? During a recent conference of [[World]] [[Religious]] leaders in [[India]], an {{Wiki|orthodox}} Rabbi put this question to Ven. [[Khandro]] [[Rimpoche]], a [[world]] renowned [[Buddhist]] [[teacher]], who took the group to visit the sites of {{Wiki|Dharamsala}}, the small town in the foothills of the [[Himalayas]] which is the residence of H.H the [[Dalai Lama]] and his government in exile. Since visiting [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] is forbidden to some {{Wiki|orthodox}} [[Jews]] for [[religious]] [[reasons]], the question was posed to her in a Museum- a place where [[Buddhist]] icons are displayed in show-cases but not actually venerated. Ven. [[Khandro]] Rimpoche`s answer reflects a genuine [[Buddhist]] [[attitude]], one which those who call themselves “[[spiritual]] but not [[religious]]” might have no difficulty relating to, while it obviously creates a challenge for those who do not espouse a pluralist [[attitude]] towards [[religion]]. She said: “When I was a small child, I read the story by Dr. Seuss called ‘The Monkey`s Race.’ It goes as follows: a [[monkey]] decides to enter a horse-race, but can only find a {{Wiki|donkey}} to ride on. Everybody makes fun of him for his naiveté to believe that he would have a chance in this race. Undeterred, the [[monkey]] puts a carrot on a stick and, as the race begins, lets the carrot dangle in front of the donkey’s {{Wiki|nose}}. The {{Wiki|donkey}}, trying to reach the carrot as best he can, runs faster and faster, bypasses all the other [[horses]] and wins the race.” We stubborn [[human beings]] are just like the {{Wiki|donkey}},” explained [[Khandro]] [[Rimpoche]], “and the [[religions]] are like the carrots which make us stubborn [[beings]] move. It does not {{Wiki|matter}} what the carrot looks like or what it is called – as long as it makes us move it is useful and fulfills its raison d`être.” | + | What is the [[Buddhist]] [[attitude]] to [[religious]] [[beliefs]], including [[belief]] in [[God]]? During a recent conference of [[World]] [[Religious]] leaders in [[India]], an {{Wiki|orthodox}} Rabbi put this question to Ven. [[Khandro]] [[Rimpoche]], a [[world]] renowned [[Buddhist]] [[teacher]], who took the group to visit the sites of {{Wiki|Dharamsala}}, the small town in the foothills of the [[Himalayas]] which is the residence of H.H the [[Dalai Lama]] and his government in exile. Since visiting [[Buddhist]] [[temples]] is forbidden to some {{Wiki|orthodox}} [[Jews]] for [[religious]] [[reasons]], the question was posed to her in a Museum- a place where [[Buddhist]] icons are displayed in show-cases but not actually venerated. Ven. [[Khandro]] Rimpoche`s answer reflects a genuine [[Buddhist]] [[attitude]], one which those who call themselves “[[spiritual]] but not [[religious]]” might have no difficulty relating to, while it obviously creates a challenge for those who do not espouse a {{Wiki|pluralist}} [[attitude]] towards [[religion]]. She said: “When I was a small child, I read the story by Dr. Seuss called ‘The Monkey`s Race.’ It goes as follows: a [[monkey]] decides to enter a horse-race, but can only find a {{Wiki|donkey}} to ride on. Everybody makes fun of him for his naiveté to believe that he would have a chance in this race. Undeterred, the [[monkey]] puts a carrot on a stick and, as the race begins, lets the carrot dangle in front of the donkey’s {{Wiki|nose}}. The {{Wiki|donkey}}, trying to reach the carrot as best he can, runs faster and faster, bypasses all the other [[horses]] and wins the race.” We stubborn [[human beings]] are just like the {{Wiki|donkey}},” explained [[Khandro]] [[Rimpoche]], “and the [[religions]] are like the carrots which make us stubborn [[beings]] move. It does not {{Wiki|matter}} what the carrot looks like or what it is called – as long as it makes us move it is useful and fulfills its raison d`être.” |

| − | In the following pages I will look at the [[phenomenon]] of [[Buddhism]] in the [[West]] as the [[spiritual]] carrot that makes [[people]] move, or rather, sit in [[meditation]] in increasing numbers. To do so, some background [[information]] about basic [[Buddhist teaching]] and the development of [[Buddhism]] in the [[West]] is necessary. For the latter part, I will have to limit myself to the US and {{Wiki|Germany}}. The focus here is on issues that inevitably emerge when a [[religion]] is transplanted from one {{Wiki|cultural}} context to another. What happens to a [[patriarchal]] [[tradition]] in a {{Wiki|Western}} context, which is shaped by democratic ideals, women’s aspirations and their inroads into [[leadership]] positions? How is genuine practice affected by a {{Wiki|culture}} that expects instant gratification and quick fixes? What is the relationship between {{Wiki|ethnic}} [[Buddhists]] and {{Wiki|Western}} converts? This also touches on one of central questions to be raised here, one that relates to the fundamental [[Buddhist teaching]] of [[No-Self]] as taken in a {{Wiki|Western}} context, wherein the strong emphasis on {{Wiki|individualism}} and the fulfillment of one’s [[dreams]] is diametrically opposed to the {{Wiki|Asian}} notion of {{Wiki|community}} as being more important than the {{Wiki|individual}}. Is [[Buddhism]], as some critics put it, just a “psychospice of self-acceptance” for those who have everything, “some rare ‘inner herb’ of guilt-free self-satisfaction?” And does the use of [[Buddhist]] terms disguise the fact that “fundamental {{Wiki|Western}} attitudes about [[self]], {{Wiki|society}} and [[consciousness]] have not changed much?”1 Or, more seriously, does the [[Buddhist]] carrot, in the words of Slavoj Zizek, turn out to be a “fetish,” which functions as the perfect ideological supplement to capitalist dynamics? The [[concern]] is that the commercialization of [[Buddhism]] in market and media and its growing popularity as part of the wellness {{Wiki|culture}} threaten to make the [[dharma]] into a middle-class commodity that mainly caters to the consumerist drives of the {{Wiki|individual}} needs; and this [[concern]] needs to be seriously addressed. Does [[Buddhist]] [[spirituality]] in the [[West]] lead to self-indulgence, rather than [[self-realization]]? Or does it open up a new and creative venue, which leads to [[transformation]] and, in some cases, even a new [[appreciation]] of the [[religion]] of one’s childhood? Before turning to these questions, some explanations about basic {{Wiki|tenets}} of [[Buddhist teaching]] and development are in order. | + | In the following pages I will look at the [[phenomenon]] of [[Buddhism]] in the [[West]] as the [[spiritual]] carrot that makes [[people]] move, or rather, sit in [[meditation]] in increasing numbers. To do so, some background [[information]] about basic [[Buddhist teaching]] and the [[development]] of [[Buddhism]] in the [[West]] is necessary. For the latter part, I will have to limit myself to the US and {{Wiki|Germany}}. The focus here is on issues that inevitably emerge when a [[religion]] is transplanted from one {{Wiki|cultural}} context to another. What happens to a [[patriarchal]] [[tradition]] in a {{Wiki|Western}} context, which is shaped by democratic ideals, women’s [[aspirations]] and their inroads into [[leadership]] positions? How is genuine practice affected by a {{Wiki|culture}} that expects instant gratification and quick fixes? What is the relationship between {{Wiki|ethnic}} [[Buddhists]] and {{Wiki|Western}} converts? This also touches on one of central questions to be raised here, one that relates to the fundamental [[Buddhist teaching]] of [[No-Self]] as taken in a {{Wiki|Western}} context, wherein the strong {{Wiki|emphasis}} on {{Wiki|individualism}} and the fulfillment of one’s [[dreams]] is diametrically opposed to the {{Wiki|Asian}} notion of {{Wiki|community}} as being more important than the {{Wiki|individual}}. Is [[Buddhism]], as some critics put it, just a “psychospice of self-acceptance” for those who have everything, “some rare ‘inner herb’ of guilt-free [[self-satisfaction]]?” And does the use of [[Buddhist]] terms disguise the fact that “fundamental {{Wiki|Western}} attitudes about [[self]], {{Wiki|society}} and [[consciousness]] have not changed much?”1 Or, more seriously, does the [[Buddhist]] carrot, in the words of Slavoj Zizek, turn out to be a “fetish,” which functions as the {{Wiki|perfect}} {{Wiki|ideological}} supplement to capitalist dynamics? The [[concern]] is that the commercialization of [[Buddhism]] in market and media and its growing [[popularity]] as part of the wellness {{Wiki|culture}} threaten to make the [[dharma]] into a middle-class commodity that mainly caters to the consumerist drives of the {{Wiki|individual}} needs; and this [[concern]] needs to be seriously addressed. Does [[Buddhist]] [[spirituality]] in the [[West]] lead to self-indulgence, rather than [[self-realization]]? Or does it open up a new and creative venue, which leads to [[transformation]] and, in some cases, even a new [[appreciation]] of the [[religion]] of one’s childhood? Before turning to these questions, some explanations about basic {{Wiki|tenets}} of [[Buddhist teaching]] and [[development]] are in order. |

1. The [[Indian]] and {{Wiki|Asian}} beginnings | 1. The [[Indian]] and {{Wiki|Asian}} beginnings | ||

| − | The [[Wikipedia:canonical|canonical]] stories paint a very colorful and detailed picture of the [[life]] that the [[future Buddha]], young {{Wiki|prince}} [[Shakyamuni]] [[Gautama]], led before his quest for [[enlightenment]]. Sheltered by his father from any [[sight]] that might make him question or abandon his care-free [[life]] of {{Wiki|luxury}}, he had not one but three {{Wiki|palaces}}, and was surrounded by beautiful women, entertaining him with {{Wiki|music}} and dances and waiting to fulfill his every wish. [[Shakyamuni]] was described as the best wrestler and archer, trained in all the sports and [[arts]] of his [[time]]. Led by curiosity to leave the palace, he encountered in succession a sick [[person]], and old [[person]] and a corpse, which, for the very first [[time]], brought home to him the [[reality]] of [[sickness]], [[old age]] and [[death]]. The last [[person]] he encountered on this excursion was a [[religious]] renunciant, whose [[serenity]] and [[contentment]] made [[Shakyamuni]] realize that his own life-style, which could be seen as the fulfillment of every {{Wiki|modern}} [[dream]] of a good and healthy [[life]], did not give him lasting fulfillment and [[happiness]]. And so he left his palace, his wife and young son in the middle of the night to embark on an [[ascetic]] [[path]] of [[renunciation]] in his search for [[enlightenment]]. Enduring every kind of hardship and almost starving himself to [[death]], he now saw his former [[life]] of [[physical]] {{Wiki|comfort}} and [[mental]] complacency as the enemy to overcome. However, after six years of extreme austerities, he [[realized]] that self-denial did not bring him any closer to [[understanding]] and [[happiness]]. This is when he decided to take the [[middle path]] between [[self-mortification]] and self-indulgence, and, not withstanding the [[criticism]] of his fellow-ascetics, he bathed, had some [[food]], and then attained [[enlightenment]] under the [[Bodhi tree]] at the rise of the morning star. | + | The [[Wikipedia:canonical|canonical]] stories paint a very colorful and detailed picture of the [[life]] that the [[future Buddha]], young {{Wiki|prince}} [[Shakyamuni]] [[Gautama]], led before his quest for [[enlightenment]]. Sheltered by his father from any [[sight]] that might make him question or abandon his care-free [[life]] of {{Wiki|luxury}}, he had not one but three {{Wiki|palaces}}, and was surrounded by beautiful women, entertaining him with {{Wiki|music}} and dances and waiting to fulfill his every wish. [[Shakyamuni]] was described as the best wrestler and archer, trained in all the sports and [[arts]] of his [[time]]. Led by curiosity to leave the palace, he encountered in succession a sick [[person]], and old [[person]] and a corpse, which, for the very first [[time]], brought [[home]] to him the [[reality]] of [[sickness]], [[old age]] and [[death]]. The last [[person]] he encountered on this excursion was a [[religious]] renunciant, whose [[serenity]] and [[contentment]] made [[Shakyamuni]] realize that his own life-style, which could be seen as the fulfillment of every {{Wiki|modern}} [[dream]] of a good and healthy [[life]], did not give him lasting fulfillment and [[happiness]]. And so he left his palace, his wife and young son in the middle of the night to embark on an [[ascetic]] [[path]] of [[renunciation]] in his search for [[enlightenment]]. Enduring every kind of hardship and almost starving himself to [[death]], he now saw his former [[life]] of [[physical]] {{Wiki|comfort}} and [[mental]] complacency as the enemy to overcome. However, after six years of extreme austerities, he [[realized]] that self-denial did not bring him any closer to [[understanding]] and [[happiness]]. This is when he decided to take the [[middle path]] between [[self-mortification]] and self-indulgence, and, not withstanding the [[criticism]] of his fellow-ascetics, he bathed, had some [[food]], and then [[attained]] [[enlightenment]] under the [[Bodhi tree]] at the rise of the morning {{Wiki|star}}. |

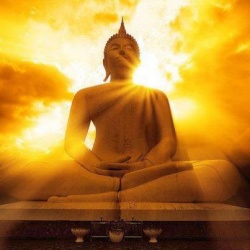

| − | This [[enlightenment]] [[experience]], which practitioners of [[Buddhist meditation]] strive also to attain, is described as a state of total freedom and perfect [[peace]]. It is said that the [[Buddha]] remained seated for seven days, rapt in [[bliss]] and [[joy]], until [[compassion]] eventually moved him to rise from his seat of [[bliss]] in order to share his discovery with his companions and others. [[Tradition]] holds that, from this point on, the [[Buddha]] became the [[teacher]] of both [[devas]] ([[divinities]]) and [[human beings]]. | + | This [[enlightenment]] [[experience]], which practitioners of [[Buddhist meditation]] strive also to attain, is described as a state of total freedom and {{Wiki|perfect}} [[peace]]. It is said that the [[Buddha]] remained seated for seven days, rapt in [[bliss]] and [[joy]], until [[compassion]] eventually moved him to rise from his seat of [[bliss]] in order to share his discovery with his companions and others. [[Tradition]] holds that, from this point on, the [[Buddha]] became the [[teacher]] of both [[devas]] ([[divinities]]) and [[human beings]]. |

| − | The [[teaching]], called the [[Dharma]], was {{Wiki|revolutionary}}. In the [[Hindu]] [[tradition]], [[dharma]] referred to the [[duty]] of every member of the {{Wiki|society}} to live according to the norms prescribed by the [[caste]] system. The [[birth]] into one of the four [[castes]] was seen as determined by [[karma]] – by a [[fate]] beyond one’s control, a result created by [[actions]] in previous [[lives]]. In the [[Buddhist]] usage, however, [[dharma]] is primarily the liberating [[truth]] [[realized]] by the [[Awakened one]], and connected to this, the [[teaching]] leading to this [[truth]]. A [[teaching]] such as “I do not call one a [[brahmana]] because of one`s origin, or one`s mother. Such is indeed [[arrogant]], and is wealthy: but the poor who is free from [[attachments]], that one I call a [[brahmana]]. That one I call indeed a [[brahmana]] who is free from [[anger]], dutiful, [[virtuous]], without appetites, who is subdued and has received one`s last [[body]] (of birth)…..”2 challenged the [[religious]] and {{Wiki|political}} system of Brahamanism, since it ascribed [[nobility]] not to [[birth]], but to an [[ethical]] way of [[life]] and a [[state of mind]] perfected by practice. This emphasis on {{Wiki|behavior}} rather than {{Wiki|status}} in the {{Wiki|social}} {{Wiki|hierarchy}} both overturned the fatalistic implications of [[karma]] and served to affirm that the worth of a [[human being]] depends on one’s [[actions]], not on [[birth]]. Today, most [[Indian]] [[Buddhists]] do in fact come from the bottom rank of {{Wiki|society}}, from the [[caste]] of the Untouchables. | + | The [[teaching]], called the [[Dharma]], was {{Wiki|revolutionary}}. In the [[Hindu]] [[tradition]], [[dharma]] referred to the [[duty]] of every member of the {{Wiki|society}} to live according to the norms prescribed by the [[caste]] system. The [[birth]] into one of the four [[castes]] was seen as determined by [[karma]] – by a [[fate]] beyond one’s control, a result created by [[actions]] in previous [[lives]]. In the [[Buddhist]] usage, however, [[dharma]] is primarily the liberating [[truth]] [[realized]] by the [[Awakened one]], and connected to this, the [[teaching]] leading to this [[truth]]. A [[teaching]] such as “I do not call one a [[brahmana]] because of one`s origin, or one`s mother. Such is indeed [[arrogant]], and is wealthy: but the poor who is free from [[attachments]], that one I call a [[brahmana]]. That one I call indeed a [[brahmana]] who is free from [[anger]], dutiful, [[virtuous]], without appetites, who is subdued and has received one`s last [[body]] (of birth)…..”2 challenged the [[religious]] and {{Wiki|political}} system of Brahamanism, since it ascribed [[nobility]] not to [[birth]], but to an [[ethical]] way of [[life]] and a [[state of mind]] perfected by practice. This {{Wiki|emphasis}} on {{Wiki|behavior}} rather than {{Wiki|status}} in the {{Wiki|social}} {{Wiki|hierarchy}} both overturned the fatalistic implications of [[karma]] and served to affirm that the worth of a [[human being]] depends on one’s [[actions]], not on [[birth]]. Today, most [[Indian]] [[Buddhists]] do in fact come from the bottom rank of {{Wiki|society}}, from the [[caste]] of the Untouchables. |

In the {{Wiki|discourse}} that is [[traditionally]] regarded as the first after his [[enlightenment]], the [[Buddha]], based on his own recent [[experience]], [[affirmed]] the importance of the “[[Middle Way]]” between the [[two extremes]] of {{Wiki|sensual}} {{Wiki|indulgence}} and [[self-mortification]]. This was followed by the “[[Four Noble Truths]],” a {{Wiki|realistic}} [[teaching]] which holds that [[life]], as most of us [[experience]] it, is marked by [[dukkha]], by a [[sense]] of dissatisfactoriness, of unfulfilled longing or [[suffering]]. The [[cause]] of this dissatisfactoriness is [[craving]] for finite things – the high-powered job, the house of one`s [[dreams]], the {{Wiki|ideal}} partner, the vacation in the Carribean, etc, etc. From the [[Buddhist]] point of [[view]], pursuing these kinds of things does not lead to true [[self-realization]] but only results in more [[craving]], and therefore more [[dissatisfaction]]. But [[human beings]] do not only [[crave]] for finite things. On a deeper level, they [[crave]] for “[[existence]],” which means the [[desire]] to perpetuate ourselves in some [[form]] or other in the attempt to negate our own {{Wiki|mortality}}. The opposite side of this is “[[craving for non-existence]],” the [[sense]] that the only way out of the constraints of the [[human]] [[condition]] is by putting an end to it. For example, the high rate of {{Wiki|suicide}} among young [[people]] who cannot bear the [[stress]] created by our highly technological {{Wiki|societies}} is an indicator for the wide occurrence of this kind of [[craving]]. | In the {{Wiki|discourse}} that is [[traditionally]] regarded as the first after his [[enlightenment]], the [[Buddha]], based on his own recent [[experience]], [[affirmed]] the importance of the “[[Middle Way]]” between the [[two extremes]] of {{Wiki|sensual}} {{Wiki|indulgence}} and [[self-mortification]]. This was followed by the “[[Four Noble Truths]],” a {{Wiki|realistic}} [[teaching]] which holds that [[life]], as most of us [[experience]] it, is marked by [[dukkha]], by a [[sense]] of dissatisfactoriness, of unfulfilled longing or [[suffering]]. The [[cause]] of this dissatisfactoriness is [[craving]] for finite things – the high-powered job, the house of one`s [[dreams]], the {{Wiki|ideal}} partner, the vacation in the Carribean, etc, etc. From the [[Buddhist]] point of [[view]], pursuing these kinds of things does not lead to true [[self-realization]] but only results in more [[craving]], and therefore more [[dissatisfaction]]. But [[human beings]] do not only [[crave]] for finite things. On a deeper level, they [[crave]] for “[[existence]],” which means the [[desire]] to perpetuate ourselves in some [[form]] or other in the attempt to negate our own {{Wiki|mortality}}. The opposite side of this is “[[craving for non-existence]],” the [[sense]] that the only way out of the constraints of the [[human]] [[condition]] is by putting an end to it. For example, the high rate of {{Wiki|suicide}} among young [[people]] who cannot bear the [[stress]] created by our highly technological {{Wiki|societies}} is an indicator for the wide occurrence of this kind of [[craving]]. | ||

| − | All these different [[forms]] of [[craving]] are attributed to a basic [[ignorance]] about the way things are, about what we really are. In contrast to the {{Wiki|theistic}} [[traditions]], [[Buddhism]] does not hold that there is an {{Wiki|individual}} [[self]] or [[eternal]] [[soul]] ([[atman]]), which is created by [[God]] and will eventually return to [[God]]. Rather, what we call the [[self]], is the coming together of the “five constituents of being” ([[skandhas]]), namely [[bodily]] [[form]], [[sensation]], [[perception]], [[mental formation]] and [[consciousness]]. The [[Buddha]] clearly declared that [[no self]] can be found in any of these, that they come together because of [[karmic]] [[causes]] and [[conditions]], and that they will disperse again when these [[conditions]] no longer pertain. Like everything else in the [[world]], we are marked by [[impermanence]], and like everything else in the [[world]], we are thoroughly interconnected and depend on everybody and everything else for [[our own existence]]. In [[Buddhist teaching]], the notion of an {{Wiki|independent}}, {{Wiki|individual}} [[self]] is the [[root]] of the [[illusion]] and [[suffering]] because it gives rise to {{Wiki|distinction}} between [[self]] and other, and with that to likes and aversions, [[lust]], [[greed]] and [[ill-will]] and [[anger]]. In short, it leads us to behave in ways that create [[suffering]] for ourselves and for others, in ways that disregard our deep interconnectedness. It is therefore the opposite of true [[self-realization]]. | + | All these different [[forms]] of [[craving]] are attributed to a basic [[ignorance]] about the way things are, about what we really are. In contrast to the {{Wiki|theistic}} [[traditions]], [[Buddhism]] does not hold that there is an {{Wiki|individual}} [[self]] or [[eternal]] [[soul]] ([[atman]]), which is created by [[God]] and will eventually return to [[God]]. Rather, what we call the [[self]], is the coming together of the “five constituents of being” ([[skandhas]]), namely [[bodily]] [[form]], [[sensation]], [[perception]], [[mental formation]] and [[consciousness]]. The [[Buddha]] clearly declared that [[no self]] can be found in any of these, that they come together because of [[karmic]] [[causes]] and [[conditions]], and that they will disperse again when these [[conditions]] no longer pertain. Like everything else in the [[world]], we are marked by [[impermanence]], and like everything else in the [[world]], we are thoroughly interconnected and depend on everybody and everything else for [[our own existence]]. In [[Buddhist teaching]], the notion of an {{Wiki|independent}}, {{Wiki|individual}} [[self]] is the [[root]] of the [[illusion]] and [[suffering]] because it gives rise to {{Wiki|distinction}} between [[self]] and other, and with that to likes and aversions, [[lust]], [[greed]] and [[ill-will]] and [[anger]]. In short, it leads us to behave in ways that create [[suffering]] for ourselves and for others, in ways that [[disregard]] our deep interconnectedness. It is therefore the opposite of true [[self-realization]]. |

But there is a way to end [[dukkha]], and this way is the [[Eightfold Noble Path]], which consists of a [[moral]] and responsible way of [[life]], [[meditation]] and [[insight]]. The practice of this [[path]] transforms [[ignorance]] into [[wisdom]] and eventually leads to the total [[liberation]] or [[Nirvana]], the state which the [[Buddha]] [[experienced]] in his enlightenment.3 | But there is a way to end [[dukkha]], and this way is the [[Eightfold Noble Path]], which consists of a [[moral]] and responsible way of [[life]], [[meditation]] and [[insight]]. The practice of this [[path]] transforms [[ignorance]] into [[wisdom]] and eventually leads to the total [[liberation]] or [[Nirvana]], the state which the [[Buddha]] [[experienced]] in his enlightenment.3 | ||

| − | As the [[Buddha]] started to attract more and more [[disciples]] with his teachings, he founded the [[monk’s]] order on the premise that freedom from [[worldly]] cares would be the most congenial way of [[life]] to practice [[meditation]] and [[insight]]. The [[monks]] were supported by lay-people, who strove to create [[spiritual]] [[merits]] for themselves and their family members by [[giving alms]] to the [[monks]] and {{Wiki|donations}} to the [[monastery]]. Since in the [[Indian]] {{Wiki|society}} of that [[time]], it was [[unthinkable]] for women to remain unmarried and live {{Wiki|independently}}, the [[Buddha]] at first refused permission to found a nun’s order, but later agreed, even though the [[nuns]] order was placed under strict supervision by the [[monks]]. Also, the number of [[precepts]] the [[nuns]] had to observe was much higher than that of the [[monks]]. | + | As the [[Buddha]] started to attract more and more [[disciples]] with his teachings, he founded the [[monk’s]] order on the premise that freedom from [[worldly]] cares would be the most congenial way of [[life]] to practice [[meditation]] and [[insight]]. The [[monks]] were supported by lay-people, who strove to create [[spiritual]] [[merits]] for themselves and their family members by [[giving alms]] to the [[monks]] and {{Wiki|donations}} to the [[monastery]]. Since in the [[Indian]] {{Wiki|society}} of that [[time]], it was [[unthinkable]] for women to remain unmarried and live {{Wiki|independently}}, the [[Buddha]] at first refused permission to found a [[nun’s]] order, but later agreed, even though the [[nuns]] order was placed under strict supervision by the [[monks]]. Also, the number of [[precepts]] the [[nuns]] had to observe was much higher than that of the [[monks]]. |

| − | Even though the teachings of [[Buddhism]] went against the [[Brahmanic]] value system, the [[Buddha]] never called for {{Wiki|political}} [[action]] against {{Wiki|priests}} or rulers. On the contrary, he was dependent on the ruler’s support and [[protection]], and on numerous occasions, the rulers sought him out for [[spiritual]], economic and {{Wiki|political}} advice. When [[Buddhism]] entered [[China]] in the 2nd century CE, it had to adapt to the {{Wiki|Confucian}} way of [[thinking]] in order to make an inroad into the {{Wiki|culture}}. The {{Wiki|Confucian}} system was based on strictly hierarchical relationships that were modeled on the workings of the [[universe]]. The [[ruler]], the son of [[heaven]], was conceived to be as far above his [[subjects]] as the sky over the [[earth]], husbands were in a similar way just as far above their wives, children had to [[respect]] and serve their [[parents]], and younger brothers elder brothers. The only relationship considered as {{Wiki|equal}} was that between friends. {{Wiki|Disturbances}} in these relationships were [[thought]] to have potentially disastrous consequences for the harmonious functioning of {{Wiki|society}} and of the [[universe]]. | + | Even though the teachings of [[Buddhism]] went against the [[Brahmanic]] value system, the [[Buddha]] never called for {{Wiki|political}} [[action]] against {{Wiki|priests}} or rulers. On the contrary, he was dependent on the ruler’s support and [[protection]], and on numerous occasions, the rulers sought him out for [[spiritual]], economic and {{Wiki|political}} advice. When [[Buddhism]] entered [[China]] in the 2nd century CE, it had to adapt to the {{Wiki|Confucian}} way of [[thinking]] in order to make an inroad into the {{Wiki|culture}}. The {{Wiki|Confucian}} system was based on strictly hierarchical relationships that were modeled on the workings of the [[universe]]. The [[ruler]], the son of [[heaven]], was conceived to be as far above his [[subjects]] as the sky over the [[earth]], husbands were in a similar way just as far above their wives, children had to [[respect]] and serve their [[parents]], and younger brothers elder brothers. The only relationship considered as {{Wiki|equal}} was that between friends. {{Wiki|Disturbances}} in these relationships were [[thought]] to have potentially disastrous {{Wiki|consequences}} for the harmonious functioning of {{Wiki|society}} and of the [[universe]]. |

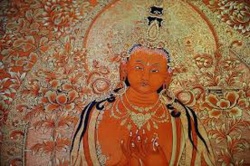

| − | Since [[Buddhism]] as a [[celibate]] [[monastic]] [[tradition]] went against the {{Wiki|Confucian}} {{Wiki|ideal}} of filial {{Wiki|behavior}}, which involves taking care of one’s [[parents]] and producing sons to pass on the family [[name]] and carry out the prescribed [[rituals]] of {{Wiki|ancestor}} {{Wiki|worship}}, {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhists]] propagated [[funeral]] and memorial [[rites]] conducted by the [[monks]] as the most filial and efficient way of ensuring deceased family members a safe passage to the other [[world]]. In this way, they also secured the financial support of their [[monasteries]]. At the same [[time]], the notion that lay persons were not only there to support the practice of the [[monks and nuns]] but they themselves could also achieve [[enlightenment]] in their own right, gained popularity in [[China]] with the translation of the [[Vimalakirti Sutra]]. [[Vimalakirti]] is described as a [[householder]] and city elder, whose [[enlightened]] way of [[life]] does not even exclude visits to the {{Wiki|prostitutes}} of the town and who easily beats even the [[disciples]] of the [[Buddha]] in [[dharma]] combats. And since [[Buddhism]] could not have established itself in [[China]] without the support of the rulers, it propagated the [[idea]] of the [[emperor]] as the [[Chakravartin]], literally, the “[[Turner of the Wheel]],” the [[enlightened]] [[universal monarch]] who spreads the [[Dharma]]. This title originally designated the [[Buddha]] himself, but was first conferred to the [[Indian]] {{Wiki|monarch}} [[Ashoka]], who had adopted [[Buddhism]] as state [[religion]] in the 3rd Cent. BCE. In this way, [[Buddhism]] spread through the {{Wiki|patronage}} of the rulers, who sponsored the building of [[monasteries]], text translations, and works of [[art]], including the splendid [[Buddhist]] rock carvings in places such as [[Loyang]] or Yungang. | + | Since [[Buddhism]] as a [[celibate]] [[monastic]] [[tradition]] went against the {{Wiki|Confucian}} {{Wiki|ideal}} of filial {{Wiki|behavior}}, which involves taking care of one’s [[parents]] and producing sons to pass on the family [[name]] and carry out the prescribed [[rituals]] of {{Wiki|ancestor}} {{Wiki|worship}}, {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhists]] propagated [[funeral]] and memorial [[rites]] conducted by the [[monks]] as the most filial and efficient way of ensuring deceased family members a safe passage to the other [[world]]. In this way, they also secured the financial support of their [[monasteries]]. At the same [[time]], the notion that lay persons were not only there to support the practice of the [[monks and nuns]] but they themselves could also achieve [[enlightenment]] in their own right, gained [[popularity]] in [[China]] with the translation of the [[Vimalakirti Sutra]]. [[Vimalakirti]] is described as a [[householder]] and city elder, whose [[enlightened]] way of [[life]] does not even exclude visits to the {{Wiki|prostitutes}} of the town and who easily beats even the [[disciples]] of the [[Buddha]] in [[dharma]] combats. And since [[Buddhism]] could not have established itself in [[China]] without the support of the rulers, it propagated the [[idea]] of the [[emperor]] as the [[Chakravartin]], literally, the “[[Turner of the Wheel]],” the [[enlightened]] [[universal monarch]] who spreads the [[Dharma]]. This title originally designated the [[Buddha]] himself, but was first conferred to the [[Indian]] {{Wiki|monarch}} [[Ashoka]], who had adopted [[Buddhism]] as state [[religion]] in the 3rd Cent. BCE. In this way, [[Buddhism]] spread through the {{Wiki|patronage}} of the rulers, who sponsored the building of [[monasteries]], text translations, and works of [[art]], including the splendid [[Buddhist]] rock carvings in places such as [[Loyang]] or Yungang. |

The two {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhist traditions]] most well-known in the [[West]], [[traditions]] that spread with all of their {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|cultural}} {{Wiki|accompaniments}} first to [[Korea]] and [[Japan]], are Ch`an ( [[Japanese]], [[Zen]]) [[Buddhism]] and [[Pure Land Buddhism]]. Ch`an is the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[word]] for the [[Sanskrit]] [[Dhyana]], and means the [[meditative]] stages arrived at by [[Shakyamuni]] in his search for [[enlightenment]]. The beginnings of the [[Zen]] [[tradition]] are attributed to the legendary coming of the [[Indian]] [[Patriarch]] [[Bodhidharma]] to [[China]] in the 5th century, who, after having told the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[emperor]] that his material sponsorship of [[Buddhism]] was of no [[merit]] whatsoever, went off to sit in a {{Wiki|cave}} facing a wall for the remaining nine years of his [[life]]. A four line verse dated from c. 1008 describes [[Zen]]: | The two {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhist traditions]] most well-known in the [[West]], [[traditions]] that spread with all of their {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|cultural}} {{Wiki|accompaniments}} first to [[Korea]] and [[Japan]], are Ch`an ( [[Japanese]], [[Zen]]) [[Buddhism]] and [[Pure Land Buddhism]]. Ch`an is the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[word]] for the [[Sanskrit]] [[Dhyana]], and means the [[meditative]] stages arrived at by [[Shakyamuni]] in his search for [[enlightenment]]. The beginnings of the [[Zen]] [[tradition]] are attributed to the legendary coming of the [[Indian]] [[Patriarch]] [[Bodhidharma]] to [[China]] in the 5th century, who, after having told the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[emperor]] that his material sponsorship of [[Buddhism]] was of no [[merit]] whatsoever, went off to sit in a {{Wiki|cave}} facing a wall for the remaining nine years of his [[life]]. A four line verse dated from c. 1008 describes [[Zen]]: | ||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

Sees into one’s [[nature]], becoming Buddha.4 | Sees into one’s [[nature]], becoming Buddha.4 | ||

| − | Differently from the Zen-tradition, which emphasizes [[meditation]] and {{Wiki|individual}} [[effort]] to attain the enlightenment-experience, which, as described above, is direct and intuitive, the [[Pure Land]] [[tradition]] holds that, ultimately, {{Wiki|salvation}} is only possible through the saving grace of [[Buddha Amitabha]] ([[Japanese]], [[Amida]]), who comes to guide [[people]] from their death-bed to [[rebirth]] in the [[Pure Land]]. While these two schools are clearly distinguished from each other in both [[Japan]] and the [[West]], {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhists]] have always practiced a mixed [[form]], which combines Zen-meditation and study of the [[Zen]] texts with [[chanting]] of [[Pure Land]] texts and [[prayers]]. | + | Differently from the Zen-tradition, which emphasizes [[meditation]] and {{Wiki|individual}} [[effort]] to attain the enlightenment-experience, which, as described above, is direct and intuitive, the [[Pure Land]] [[tradition]] holds that, ultimately, {{Wiki|salvation}} is only possible through the saving grace of [[Buddha Amitabha]] ([[Japanese]], [[Amida]]), who comes to [[guide]] [[people]] from their death-bed to [[rebirth]] in the [[Pure Land]]. While these two schools are clearly {{Wiki|distinguished}} from each other in both [[Japan]] and the [[West]], {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhists]] have always practiced a mixed [[form]], which combines Zen-meditation and study of the [[Zen]] texts with [[chanting]] of [[Pure Land]] texts and [[prayers]]. |

| − | With this very short overview of the [[Indian]] and {{Wiki|Asian}} background, we can now turn to the development of [[Buddhism]] in the [[West]]. | + | With this very short overview of the [[Indian]] and {{Wiki|Asian}} background, we can now turn to the [[development]] of [[Buddhism]] in the [[West]]. |

2) [[Buddhism]] in the [[West]] | 2) [[Buddhism]] in the [[West]] | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

[[Buddhist]] source texts became known in {{Wiki|Europe}} only in the 19th.century, but {{Wiki|enthusiastic}} reports about {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|civilization}} and [[religions]] by the {{Wiki|Jesuit}} [[missionaries]] around Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) already inspired [[enlightenment]] thinkers such as Gottfried Wilhelm {{Wiki|Leibniz}} (1646-1716) and others, who admired [[China’s]] {{Wiki|culture}} of [[religious]] [[tolerance]] in the wake of the havoc created by the 30 years of [[war]] between Catholics and Protestants. [[Buddhism]] attracted such influential intellectuals as {{Wiki|Schopenhauer}}, {{Wiki|Nietzsche}}, Wagner and {{Wiki|Rhys Davids}}, as well as the [[transcendentalists]] Ralph Waldo Emerson and David Thoreau, who saw in it a welcome alternative to the {{Wiki|Christian}} [[religion]] and bourgeois {{Wiki|society}} which they rejected. Herman Hesse`s [[Siddharta]] which was published in 1922 influenced at least two generations of readers, and is still on the list of required readings in some high schools in the US. | [[Buddhist]] source texts became known in {{Wiki|Europe}} only in the 19th.century, but {{Wiki|enthusiastic}} reports about {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|civilization}} and [[religions]] by the {{Wiki|Jesuit}} [[missionaries]] around Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) already inspired [[enlightenment]] thinkers such as Gottfried Wilhelm {{Wiki|Leibniz}} (1646-1716) and others, who admired [[China’s]] {{Wiki|culture}} of [[religious]] [[tolerance]] in the wake of the havoc created by the 30 years of [[war]] between Catholics and Protestants. [[Buddhism]] attracted such influential intellectuals as {{Wiki|Schopenhauer}}, {{Wiki|Nietzsche}}, Wagner and {{Wiki|Rhys Davids}}, as well as the [[transcendentalists]] Ralph Waldo Emerson and David Thoreau, who saw in it a welcome alternative to the {{Wiki|Christian}} [[religion]] and bourgeois {{Wiki|society}} which they rejected. Herman Hesse`s [[Siddharta]] which was published in 1922 influenced at least two generations of readers, and is still on the list of required readings in some high schools in the US. | ||

| − | Even though the development of [[Buddhism]] in the [[West]] followed different trajectories in different countries, there are certain common [[characteristics]]. One of them is the emphasis on an existential and [[meditative]] search for new ways of living. Personal guidance of {{Wiki|Asian}} [[teachers]] who came to the [[West]] supplanted the earlier purely [[intellectual]] and {{Wiki|academic}} [[interest]] in [[Buddhism]]. Also, many young [[people]] went to [[South]] and {{Wiki|South East Asia}} in the 1960`s in their search for an alternative way of [[life]]. Quite a few of them returned well-versed in the [[languages]] and [[scriptures]] as well as [[spiritual]] practices of [[Buddhism]] and started to found [[Buddhist Studies]] departments in American {{Wiki|universities}} or [[meditation centers]]. Even though some of the {{Wiki|Western}} converts to [[Buddhism]] profess and practice [[monastic]] [[vows]] (often temporarily), the vast majority of {{Wiki|Western}} [[Buddhists]] are [[lay people]] and practice a Westernized from of [[Buddhism]]. Differently from [[lay people]] in {{Wiki|Asian}} countries, their practice does not center on accumulating [[spiritual]] [[merit]] by supporting the [[sangha]] or donating [[stupas]]. They also generally have little [[interest]] in the prescribed [[rituals]] and {{Wiki|ceremonies}} for deceased family members. Their practice is more akin to that of the [[monks and nuns]], which focuses on [[meditation]] and study of the [[scriptures]]. However, many {{Wiki|Western}} [[Buddhists]] do not necessarily attend a center for [[meditation]] and [[dharma]] instruction on a regular basis. Many follow the increasing trend of “privatized [[religion]],” which means they follow a [[spiritual practice]] {{Wiki|independent}} of any formal allegiance to an institution and do a good portion of their practice at home. | + | Even though the [[development]] of [[Buddhism]] in the [[West]] followed different trajectories in different countries, there are certain common [[characteristics]]. One of them is the {{Wiki|emphasis}} on an existential and [[meditative]] search for new ways of living. Personal guidance of {{Wiki|Asian}} [[teachers]] who came to the [[West]] supplanted the earlier purely [[intellectual]] and {{Wiki|academic}} [[interest]] in [[Buddhism]]. Also, many young [[people]] went to [[South]] and {{Wiki|South East Asia}} in the 1960`s in their search for an alternative way of [[life]]. Quite a few of them returned well-versed in the [[languages]] and [[scriptures]] as well as [[spiritual]] practices of [[Buddhism]] and started to found [[Buddhist Studies]] departments in American {{Wiki|universities}} or [[meditation centers]]. Even though some of the {{Wiki|Western}} converts to [[Buddhism]] profess and practice [[monastic]] [[vows]] (often temporarily), the vast majority of {{Wiki|Western}} [[Buddhists]] are [[lay people]] and practice a Westernized from of [[Buddhism]]. Differently from [[lay people]] in {{Wiki|Asian}} countries, their practice does not center on accumulating [[spiritual]] [[merit]] by supporting the [[sangha]] or donating [[stupas]]. They also generally have little [[interest]] in the prescribed [[rituals]] and {{Wiki|ceremonies}} for deceased family members. Their practice is more akin to that of the [[monks and nuns]], which focuses on [[meditation]] and study of the [[scriptures]]. However, many {{Wiki|Western}} [[Buddhists]] do not necessarily attend a center for [[meditation]] and [[dharma]] instruction on a regular basis. Many follow the increasing trend of “privatized [[religion]],” which means they follow a [[spiritual practice]] {{Wiki|independent}} of any formal allegiance to an institution and do a good portion of their practice at [[home]]. |

| − | The one major event that helped [[Buddhism]] gain a breakthrough in the [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]] was the 1893 Parliament of [[World]] [[Religions]] in {{Wiki|Chicago}}, a highly publicized Interfaith event attended by such personalities as the [[Japanese]] Zen-Master [[Shaku]] Soen (1859-1919) from [[Japan]] and [[Anagarika Dharmapala]] (1864-1933) from [[Sri Lanka]], who traveled across the US and founded the first [[Buddhist]] centers there. One of the greatest popularizers of [[Buddhism]] was [[Shaku]] Soen`s [[disciple]] Suzuki Daisetzu (1870-1966), who was the first to give Westerners a systematic account of the [[enlightenment]] [[experience]] ([[Satori]]) in [[Zen]]. | + | The one major event that helped [[Buddhism]] gain a breakthrough in the [[Wikipedia:United States of America (USA)|United States]] was the 1893 Parliament of [[World]] [[Religions]] in {{Wiki|Chicago}}, a highly publicized Interfaith event attended by such personalities as the [[Japanese]] Zen-Master [[Shaku]] [[Soen]] (1859-1919) from [[Japan]] and [[Anagarika Dharmapala]] (1864-1933) from [[Sri Lanka]], who traveled across the US and founded the first [[Buddhist]] centers there. One of the greatest popularizers of [[Buddhism]] was [[Shaku]] Soen`s [[disciple]] Suzuki Daisetzu (1870-1966), who was the first to give Westerners a systematic account of the [[enlightenment]] [[experience]] ([[Satori]]) in [[Zen]]. |

Of course, {{Wiki|Asian}} [[Buddhists]], mainly from [[Japan]] and [[China]], had arrived in the US earlier in the 19th century. Most of them settled in {{Wiki|California}}, which was then in the midst of the gold-rush {{Wiki|fever}}. With more liberal immigration laws after {{Wiki|World War II}}, more immigrants arrived, also from [[Southeast]] {{Wiki|Asian}} countries and [[Korea]], and brought with them their own [[Buddhist Temple]] and {{Wiki|community}} building [[traditions]]. But to this day, these {{Wiki|ethnic}} [[Buddhists]] on the one hand, and {{Wiki|Western}} converts to [[Buddhism]] on the other, still mostly keep to themselves, without much in-depth interaction. | Of course, {{Wiki|Asian}} [[Buddhists]], mainly from [[Japan]] and [[China]], had arrived in the US earlier in the 19th century. Most of them settled in {{Wiki|California}}, which was then in the midst of the gold-rush {{Wiki|fever}}. With more liberal immigration laws after {{Wiki|World War II}}, more immigrants arrived, also from [[Southeast]] {{Wiki|Asian}} countries and [[Korea]], and brought with them their own [[Buddhist Temple]] and {{Wiki|community}} building [[traditions]]. But to this day, these {{Wiki|ethnic}} [[Buddhists]] on the one hand, and {{Wiki|Western}} converts to [[Buddhism]] on the other, still mostly keep to themselves, without much in-depth interaction. | ||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

In contrast to [[Buddhism]] in {{Wiki|Asia}} that has been largely socially conservative, the “Beat generation” of the sixties, influenced by Suzuki`s writings and those of {{Wiki|Alan Watts}} (1915-1973), discovered [[Zen Buddhism]] as an alternative way of [[thinking]]. They made it into a life-style that supported their protest against the material {{Wiki|culture}}, the puritanical work [[ethic]] and the conformity of the American middle class. Poets such as Alan Ginsberg 1926-1997), {{Wiki|Jack Kerouac}} (1922-1969) and {{Wiki|Gary Snyder}}, like many others, experimented with {{Wiki|psychedelic}} [[drugs]] and studied with [[Buddhist teachers]]. Their writings express the {{Wiki|aesthetic}} inspiration of every day [[life]], as common in [[Zen]]. Arguably the most influential work on [[Zen]] [[Buddhist teachings]] and practice is The Three Pillars of [[Zen]] edited by Philipp Kapleau (1912-2004) which was published in 1965. | In contrast to [[Buddhism]] in {{Wiki|Asia}} that has been largely socially conservative, the “Beat generation” of the sixties, influenced by Suzuki`s writings and those of {{Wiki|Alan Watts}} (1915-1973), discovered [[Zen Buddhism]] as an alternative way of [[thinking]]. They made it into a life-style that supported their protest against the material {{Wiki|culture}}, the puritanical work [[ethic]] and the conformity of the American middle class. Poets such as Alan Ginsberg 1926-1997), {{Wiki|Jack Kerouac}} (1922-1969) and {{Wiki|Gary Snyder}}, like many others, experimented with {{Wiki|psychedelic}} [[drugs]] and studied with [[Buddhist teachers]]. Their writings express the {{Wiki|aesthetic}} inspiration of every day [[life]], as common in [[Zen]]. Arguably the most influential work on [[Zen]] [[Buddhist teachings]] and practice is The Three Pillars of [[Zen]] edited by Philipp Kapleau (1912-2004) which was published in 1965. | ||

| − | With the flight of the [[Dalai Lama]] from Chinese-occupied [[Tibet]] to exile in [[India]] in 1951, [[Tibetan]] [[teachers]] of different [[lineages]] relocated to the [[West]]. One of the most important but also most controversial [[teachers]] coming to the US in 1970 was [[Chögyam Trungpa]] (1939-1987), who founded the [[Naropa Institute]] for the Study of [[Buddhism]] in 1974 and established a network of [[Tibetan]] centers of the [[Kagyu Tradition]]. The [[Theravada tradition]] is also represented in the US. The “[[Insight]] [[Meditation]] Center” in Barre, Massachussets was founded in 1976, and students of the resident [[teachers]] {{Wiki|Joseph Goldstein}} and {{Wiki|Jack Kornfield}} have brought [[mindfulness]] [[meditation practices]] into hospitals and therapeutic programs. | + | With the flight of the [[Dalai Lama]] from Chinese-occupied [[Tibet]] to exile in [[India]] in 1951, [[Tibetan]] [[teachers]] of different [[lineages]] relocated to the [[West]]. One of the most important but also most controversial [[teachers]] coming to the US in 1970 was [[Chögyam Trungpa]] (1939-1987), who founded the [[Naropa Institute]] for the Study of [[Buddhism]] in 1974 and established a network of [[Tibetan]] centers of the [[Kagyu Tradition]]. The [[Theravada tradition]] is also represented in the US. The “[[Insight]] [[Meditation]] Center” in Barre, Massachussets was founded in 1976, and students of the resident [[teachers]] {{Wiki|Joseph Goldstein}} and {{Wiki|Jack Kornfield}} have brought [[mindfulness]] [[meditation practices]] into hospitals and {{Wiki|therapeutic}} programs. |

In addition to the [[Japanese Pure Land]] ([[Shin]]) [[tradition]], which was introduced by earlier immigrants, [[Japanese]] lay movements such as [[Soka Gakkai]] and Rissho Koseikai are also growing rapidly in the US. Membership in these organizations was originally limited to those of [[Japanese]] descent, but now they are reaching out to other groups as well and are more popular with African {{Wiki|Americans}} than are other [[Buddhist]] denominations. | In addition to the [[Japanese Pure Land]] ([[Shin]]) [[tradition]], which was introduced by earlier immigrants, [[Japanese]] lay movements such as [[Soka Gakkai]] and Rissho Koseikai are also growing rapidly in the US. Membership in these organizations was originally limited to those of [[Japanese]] descent, but now they are reaching out to other groups as well and are more popular with African {{Wiki|Americans}} than are other [[Buddhist]] denominations. | ||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

In {{Wiki|Germany}}, the early stage of translating and discussing [[Buddhist scriptures]], mainly of the [[Pali]] [[tradition]], was followed by [[interest]] in the practice of [[meditation]], and finally, as in the case of the US, a [[transformation]] of [[Buddhism]] into a {{Wiki|European}} [[form]]. In the early stages, the writings of {{Wiki|Arthur Schopenhauer}} (1788-1860), who saw a similarity between [[Buddhist teachings]] on [[detachment]] and his own atheistic-pessimist [[ideas]], inspired intellectuals to translate [[Buddhist texts]] and even to join [[Buddhist]] [[monks]]’ orders in {{Wiki|Asia}}. The {{Wiki|German}} Pali-Society was founded in 1909, followed by the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Community}} for {{Wiki|Germany}} (Buddhistische Gemeinde für Deutschland), which was co-established by the {{Wiki|Physician}} Karl Seidenstücker (1876-1936) and the Jurist Georg Grimm (1868-1945). Grimm`s major work, The [[teaching of the Buddha]], the [[Religion]] of [[Reason]] ([[Die]] Lehre des [[Buddho]], [[die]] [[Religion]] der Vernunft) was printed in many editions in 1915. After {{Wiki|World War II}}, numerous groups and centers for [[Buddhism]] sprang into [[existence]]. The major [[umbrella]] organization established in 1989 is called the {{Wiki|German}} [[Buddhist]] Union (Deutsche Buddhistische Union). | In {{Wiki|Germany}}, the early stage of translating and discussing [[Buddhist scriptures]], mainly of the [[Pali]] [[tradition]], was followed by [[interest]] in the practice of [[meditation]], and finally, as in the case of the US, a [[transformation]] of [[Buddhism]] into a {{Wiki|European}} [[form]]. In the early stages, the writings of {{Wiki|Arthur Schopenhauer}} (1788-1860), who saw a similarity between [[Buddhist teachings]] on [[detachment]] and his own atheistic-pessimist [[ideas]], inspired intellectuals to translate [[Buddhist texts]] and even to join [[Buddhist]] [[monks]]’ orders in {{Wiki|Asia}}. The {{Wiki|German}} Pali-Society was founded in 1909, followed by the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|Community}} for {{Wiki|Germany}} (Buddhistische Gemeinde für Deutschland), which was co-established by the {{Wiki|Physician}} Karl Seidenstücker (1876-1936) and the Jurist Georg Grimm (1868-1945). Grimm`s major work, The [[teaching of the Buddha]], the [[Religion]] of [[Reason]] ([[Die]] Lehre des [[Buddho]], [[die]] [[Religion]] der Vernunft) was printed in many editions in 1915. After {{Wiki|World War II}}, numerous groups and centers for [[Buddhism]] sprang into [[existence]]. The major [[umbrella]] organization established in 1989 is called the {{Wiki|German}} [[Buddhist]] Union (Deutsche Buddhistische Union). | ||

| − | The emphasis on [[meditation]] together with the study of texts was initiated by the writings and teachings of three native Germans who went to {{Wiki|Asia}} and became [[monks]] there. [[Nyanatiloka]] and [[Nyanaponika]] introduced the [[Theravada tradition]], prevalent in [[South]] and South-East {{Wiki|Asian}} countries, in more depth. The break-through for Zen-Buddhism in {{Wiki|Germany}} happened with the publication of [[Zen]] in the [[Art]] of [[Archery]] ([[Zen]] und [[die]] Kunst des Bogenschießens) in 1948. It is considered the most widely read [[book]] on [[Zen]] in the {{Wiki|German}} [[language]]. [[Lama]] [[Anagarika]] Govinda`s (Ernst Lothar Hoffman, 1898-1985) famous [[book]], [[Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism]] (Grundlagen Tibetischer Mystik), published in 1957, laid the foundation for the entry of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] into the [[West]]. The pioneer who introduced the practice of [[Zen]] to [[Christians]] in both [[monasteries]] and [[meditation centers]], while always remaining a {{Wiki|Christian}} himself, was the {{Wiki|Jesuit}} priest Hugo Makibi Enomiya Lassalle (1898-1990). [[Zen]] was further spread by the work of Karlfried Graf Dürckheim (1866-1988) and his center in Todmoos/Rütte. Like Lassalle, Dürckheim was convinced that the development of a [[meditative]] [[form]] of [[consciousness]] was necessary for post-war {{Wiki|Europeans}} to be able to reconnect to their [[spiritual]] [[roots]]. | + | The {{Wiki|emphasis}} on [[meditation]] together with the study of texts was initiated by the writings and teachings of three native Germans who went to {{Wiki|Asia}} and became [[monks]] there. [[Nyanatiloka]] and [[Nyanaponika]] introduced the [[Theravada tradition]], prevalent in [[South]] and South-East {{Wiki|Asian}} countries, in more depth. The break-through for Zen-Buddhism in {{Wiki|Germany}} happened with the publication of [[Zen]] in the [[Art]] of [[Archery]] ([[Zen]] und [[die]] Kunst des Bogenschießens) in 1948. It is considered the most widely read [[book]] on [[Zen]] in the {{Wiki|German}} [[language]]. [[Lama]] [[Anagarika]] Govinda`s (Ernst Lothar Hoffman, 1898-1985) famous [[book]], [[Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism]] (Grundlagen Tibetischer Mystik), published in 1957, laid the foundation for the entry of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] into the [[West]]. The pioneer who introduced the practice of [[Zen]] to [[Christians]] in both [[monasteries]] and [[meditation centers]], while always remaining a {{Wiki|Christian}} himself, was the {{Wiki|Jesuit}} [[priest]] Hugo Makibi Enomiya Lassalle (1898-1990). [[Zen]] was further spread by the work of Karlfried Graf Dürckheim (1866-1988) and his center in Todmoos/Rütte. Like Lassalle, Dürckheim was convinced that the [[development]] of a [[meditative]] [[form]] of [[consciousness]] was necessary for post-war {{Wiki|Europeans}} to be able to reconnect to their [[spiritual]] [[roots]]. |

As already mentioned above, many [[Tibetan]] [[teachers]] came to the [[West]] after 1959, and founded centers and [[monasteries]] there. The [[monastic]] “[[Tibet]] Institute” in Rikon ([[Switzerland]]) was the first, followed by many other centers in {{Wiki|Germany}} and [[Switzerland]]. The [[Theravada tradition]] was continued by [[Ayya Khema]] (1923-1997) who founded the Buddha-Haus in Bavaria. | As already mentioned above, many [[Tibetan]] [[teachers]] came to the [[West]] after 1959, and founded centers and [[monasteries]] there. The [[monastic]] “[[Tibet]] Institute” in Rikon ([[Switzerland]]) was the first, followed by many other centers in {{Wiki|Germany}} and [[Switzerland]]. The [[Theravada tradition]] was continued by [[Ayya Khema]] (1923-1997) who founded the Buddha-Haus in Bavaria. | ||

| − | This short survey of [[Buddhism]] in the {{Wiki|USA}} and {{Wiki|Germany}} serves to show that [[Buddhism]] has a history that reaches back to the beginnings of the 19th century and even earlier; that it is well established and that it is very diverse.5 At the beginning of the 2nd millennium, the number of [[Buddhists]] in the US is an estimated 3 million, the same number as for all of {{Wiki|Europe}}. In {{Wiki|Germany}} it is about 250,000. In some sources, [[Buddhism]] is described as the fastest growing [[religion]] in the [[West]]. With this in [[mind]], we are now ready to turn to the issues that come up when one [[religion]] is transferred from one {{Wiki|cultural}} and [[religious]] context to another and assumes a popularity that outshines the lure of entrenched [[traditions]]. More particularly, we want to look at these issues while keeping in [[mind]] the question that was spelled out in the introduction: Is [[Buddhism]] a way of [[self]] [[realization]] or is it self-indulgence? And ultimately, given this question, what is the [[self]] we are {{Wiki|speaking}} about? | + | This short survey of [[Buddhism]] in the {{Wiki|USA}} and {{Wiki|Germany}} serves to show that [[Buddhism]] has a history that reaches back to the beginnings of the 19th century and even earlier; that it is well established and that it is very diverse.5 At the beginning of the 2nd millennium, the number of [[Buddhists]] in the US is an estimated 3 million, the same number as for all of {{Wiki|Europe}}. In {{Wiki|Germany}} it is about 250,000. In some sources, [[Buddhism]] is described as the fastest growing [[religion]] in the [[West]]. With this in [[mind]], we are now ready to turn to the issues that come up when one [[religion]] is transferred from one {{Wiki|cultural}} and [[religious]] context to another and assumes a [[popularity]] that outshines the lure of entrenched [[traditions]]. More particularly, we want to look at these issues while keeping in [[mind]] the question that was spelled out in the introduction: Is [[Buddhism]] a way of [[self]] [[realization]] or is it self-indulgence? And ultimately, given this question, what is the [[self]] we are {{Wiki|speaking}} about? |

a) “The [[Dharma]] is Neither {{Wiki|male}} nor Female”6 | a) “The [[Dharma]] is Neither {{Wiki|male}} nor Female”6 | ||

| − | Urged by his aunt [[Mahaprajapati]], who raised him after his mother’s [[death]], the [[Buddha]] finally granted permission to establish the [[nuns]]’ order, and thereby opened a socially viable option and [[spiritual]] [[path]] for women, which was an alternative to the [[traditional]] role of wife and mother. {{Wiki|Canonical}} texts however contain numerous misogynistic statements about women doubting their ability to become [[enlightened]], including a {{Wiki|prediction}} ascribed to the [[Buddha]] to the effect that the life-span of the [[sangha]] would {{Wiki|decline}} because of the establishment of the nun’s order. In addition to the earlier [[Pali]] sources, texts of the [[Mahayana tradition]], which spread to [[China]], [[Korea]] and [[Japan]], also contain the notion that a woman has to be [[reborn]] as a man in order to reach [[enlightenment]]. In fact, one of the [[vows]] of the [[future Buddha]] [[Amitabha]] of the [[Pure Land]], which is also echoed in other [[Mahayana texts]], is that he will not reach [[ultimate enlightenment]] unless all women who [[desire]] to give up their {{Wiki|female}} [[body]] and acquire a {{Wiki|male}} [[body]] will be [[reborn]] as men. The [[Pure Land Sutra]] maintains that there will be no women in [[paradise]], because all those [[reborn]] there will have a {{Wiki|male}} [[body]]. | + | Urged by his aunt [[Mahaprajapati]], who raised him after his mother’s [[death]], the [[Buddha]] finally granted permission to establish the [[nuns]]’ order, and thereby opened a socially viable option and [[spiritual]] [[path]] for women, which was an alternative to the [[traditional]] role of wife and mother. {{Wiki|Canonical}} texts however contain numerous misogynistic statements about women doubting their ability to become [[enlightened]], including a {{Wiki|prediction}} ascribed to the [[Buddha]] to the effect that the [[life-span]] of the [[sangha]] would {{Wiki|decline}} because of the establishment of the [[nun’s]] order. In addition to the earlier [[Pali]] sources, texts of the [[Mahayana tradition]], which spread to [[China]], [[Korea]] and [[Japan]], also contain the notion that a woman has to be [[reborn]] as a man in order to reach [[enlightenment]]. In fact, one of the [[vows]] of the [[future Buddha]] [[Amitabha]] of the [[Pure Land]], which is also echoed in other [[Mahayana texts]], is that he will not reach [[ultimate enlightenment]] unless all women who [[desire]] to give up their {{Wiki|female}} [[body]] and acquire a {{Wiki|male}} [[body]] will be [[reborn]] as men. The [[Pure Land Sutra]] maintains that there will be no women in [[paradise]], because all those [[reborn]] there will have a {{Wiki|male}} [[body]]. |

| − | The implications of texts such as these, reflecting the {{Wiki|cultural}} norms and {{Wiki|fears}} of [[patriarchal]] {{Wiki|societies}}, have been deep in {{Wiki|Asia}}. Today, women still play a secondary role in [[Buddhist]] hierarchies there, with the exception of {{Wiki|Taiwan}}. The fact that the direct [[monastic]] line of [[ordination]] for women [[died]] out in [[Sri Lanka]] in the 11th century still affects women in [[Theravada]] countries, where the authorities have been resisting the re-installment of full [[monastic]] [[ordination]] for women. [[Tibetan]] [[nuns]] have been in a similar situation. So one could pointedly ask what it was that attracted Westerners to a [[patriarchal]] [[religious]] [[tradition]] that in some way considers the {{Wiki|male}} [[self]] closer to, or even a precondition of [[enlightenment]]? Can only {{Wiki|males}} come to full [[self-realization]]? | + | The implications of texts such as these, {{Wiki|reflecting}} the {{Wiki|cultural}} norms and {{Wiki|fears}} of [[patriarchal]] {{Wiki|societies}}, have been deep in {{Wiki|Asia}}. Today, women still play a secondary role in [[Buddhist]] hierarchies there, with the exception of {{Wiki|Taiwan}}. The fact that the direct [[monastic]] line of [[ordination]] for women [[died]] out in [[Sri Lanka]] in the 11th century still affects women in [[Theravada]] countries, where the authorities have been resisting the re-installment of full [[monastic]] [[ordination]] for women. [[Tibetan]] [[nuns]] have been in a similar situation. So one could pointedly ask what it was that attracted Westerners to a [[patriarchal]] [[religious]] [[tradition]] that in some way considers the {{Wiki|male}} [[self]] closer to, or even a precondition of [[enlightenment]]? Can only {{Wiki|males}} come to full [[self-realization]]? |

| − | When [[Buddhist teachers]] from {{Wiki|Asia}} started introducing [[Buddhism]] to a lay {{Wiki|Western}} audience, these aspects were not highlighted. Women who sought out [[Buddhist teachers]] were generally accepted as students, just as men were. In the earlier stages of the introduction of [[Buddhism]] to the [[West]], most Westerners did not particularly [[concern]] themselves with the position of women in {{Wiki|Asian}} [[Buddhist]] countries, and did also not know the texts well enough to draw any conclusions one way or the other. But as [[Buddhist studies]] became a [[discipline]] in American {{Wiki|universities}} in the 70’s and 80’s, at about the same [[time]] when the women’s {{Wiki|movement}} had led to the creation of women’s studies program at {{Wiki|universities}}, these questions came up for scrutiny. Diana Paul’s [[book]] Women in [[Buddhism]], published in 1979, systematically explores statements on women in [[Buddhist]] sources and addresses the question of how {{Wiki|egalitarian}} tendencies in [[Buddhism]] came to terms with the even stronger heritage of misogyny. This was later followed up by Rita Gross’ [[Buddhism]] after Patriarchy (1993), which addresses the issue of being a [[Buddhist]] Feminist and reading [[Buddhist texts]] from a feminist {{Wiki|perspective}}. These and other [[scholars]] have pointed out that misogynist statements attributed to [[Buddha Shakyamuni]] in fact date from a later period, when the [[monastic order]] [[experienced]] [[stress]] over internal frictions and the rise of the more lay-oriented [[Mahayana]] {{Wiki|movement}}. Nevertheless, uneasiness bubbled up among women, since they could no longer be certain that [[Buddhism]] was less affected by [[patriarchal]] structures than, for example, {{Wiki|Judaism}} and [[Christianity]], [[traditions]] that many of them had left behind because of the oppressiveness of their structures vis-à-vis women. | + | When [[Buddhist teachers]] from {{Wiki|Asia}} started introducing [[Buddhism]] to a lay {{Wiki|Western}} audience, these aspects were not highlighted. Women who sought out [[Buddhist teachers]] were generally accepted as students, just as men were. In the earlier stages of the introduction of [[Buddhism]] to the [[West]], most Westerners did not particularly [[concern]] themselves with the position of women in {{Wiki|Asian}} [[Buddhist]] countries, and did also not know the texts well enough to draw any conclusions one way or the other. But as [[Buddhist studies]] became a [[discipline]] in American {{Wiki|universities}} in the 70’s and 80’s, at about the same [[time]] when the women’s {{Wiki|movement}} had led to the creation of women’s studies program at {{Wiki|universities}}, these questions came up for {{Wiki|scrutiny}}. Diana Paul’s [[book]] Women in [[Buddhism]], published in 1979, systematically explores statements on women in [[Buddhist]] sources and addresses the question of how {{Wiki|egalitarian}} {{Wiki|tendencies}} in [[Buddhism]] came to terms with the even stronger heritage of misogyny. This was later followed up by Rita Gross’ [[Buddhism]] after Patriarchy (1993), which addresses the issue of being a [[Buddhist]] Feminist and reading [[Buddhist texts]] from a feminist {{Wiki|perspective}}. These and other [[scholars]] have pointed out that misogynist statements attributed to [[Buddha Shakyamuni]] in fact date from a later period, when the [[monastic order]] [[experienced]] [[stress]] over internal frictions and the rise of the more lay-oriented [[Mahayana]] {{Wiki|movement}}. Nevertheless, uneasiness bubbled up among women, since they could no longer be certain that [[Buddhism]] was less affected by [[patriarchal]] structures than, for example, {{Wiki|Judaism}} and [[Christianity]], [[traditions]] that many of them had left behind because of the oppressiveness of their structures vis-à-vis women. |

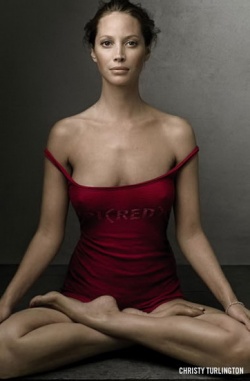

Even though the issue of [[patriarchal]] structures in [[religion]], including [[Buddhism]], remains, women in the [[West]] (and to a much lesser [[degree]] in {{Wiki|Asia}}) have assumed [[leadership]] roles in various [[Buddhist]] [[lineages]], and this especially in the Zen-tradition where fully authorized women [[teachers]] offer [[spiritual]] guidance and [[leadership]] to their [[sanghas]]. This is significant not only in terms of numbers, but also in the qualitative difference that women can make in their [[teaching]]. In the [[West]], the question of whether a woman can become [[enlightened]] or not is now considered historical, at best. Women have not only carved out their own spaces, both at American {{Wiki|universities}} and [[Buddhist]] centers, but have also been in the forefront of helping the efforts of their {{Wiki|Asian}} sisters to gain full [[monastic]] [[ordination]] and the greater [[recognition]] in {{Wiki|society}} that comes with it. Ven. [[Karma]] Lekshe Tsomo, an American who was [[ordained]] in the [[Tibetan tradition]] and currently teaches at the {{Wiki|University}} of {{Wiki|San Diego}}, is the president of Sakyadhita, an international [[Buddhist]] women’s organization. One of the organization’s many goals, which also includes the [[education]] of [[Buddhist]] girls and women in {{Wiki|Asia}}, is to help reestablish the [[Buddhist]] [[nuns]]’ order where it is not {{Wiki|present}}. As such, the organization invited the [[Dalai Lama]] to its conference in Hamburg in summer of 2007, a widely publicized event during which he promised his support for the reestablishment of the [[Tibetan]] [[nuns]]’ order. | Even though the issue of [[patriarchal]] structures in [[religion]], including [[Buddhism]], remains, women in the [[West]] (and to a much lesser [[degree]] in {{Wiki|Asia}}) have assumed [[leadership]] roles in various [[Buddhist]] [[lineages]], and this especially in the Zen-tradition where fully authorized women [[teachers]] offer [[spiritual]] guidance and [[leadership]] to their [[sanghas]]. This is significant not only in terms of numbers, but also in the qualitative difference that women can make in their [[teaching]]. In the [[West]], the question of whether a woman can become [[enlightened]] or not is now considered historical, at best. Women have not only carved out their own spaces, both at American {{Wiki|universities}} and [[Buddhist]] centers, but have also been in the forefront of helping the efforts of their {{Wiki|Asian}} sisters to gain full [[monastic]] [[ordination]] and the greater [[recognition]] in {{Wiki|society}} that comes with it. Ven. [[Karma]] Lekshe Tsomo, an American who was [[ordained]] in the [[Tibetan tradition]] and currently teaches at the {{Wiki|University}} of {{Wiki|San Diego}}, is the president of Sakyadhita, an international [[Buddhist]] women’s organization. One of the organization’s many goals, which also includes the [[education]] of [[Buddhist]] girls and women in {{Wiki|Asia}}, is to help reestablish the [[Buddhist]] [[nuns]]’ order where it is not {{Wiki|present}}. As such, the organization invited the [[Dalai Lama]] to its conference in Hamburg in summer of 2007, a widely publicized event during which he promised his support for the reestablishment of the [[Tibetan]] [[nuns]]’ order. | ||

| − | However, the road to the [[leadership]] positions that women hold in [[Buddhism]] in the [[West]] today has not always been smooth. The problem here is not only coming to terms with [[traditional]] [[patriarchal]] structures and misogynist statements but with the [[inherent]] difficulty of having a hierarchical master-disciple relationship, common in [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Asian}} {{Wiki|societies}}, transferred to a {{Wiki|Western}} context, and with the {{Wiki|ambiguity}} involved in the very personal relationship between [[teacher]] and student, especially when the [[teacher]] is a man and the student a woman or vice-versa. | + | However, the road to the [[leadership]] positions that women hold in [[Buddhism]] in the [[West]] today has not always been smooth. The problem here is not only coming to terms with [[traditional]] [[patriarchal]] structures and misogynist statements but with the [[inherent]] difficulty of having a hierarchical master-disciple relationship, common in [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Asian}} {{Wiki|societies}}, transferred to a {{Wiki|Western}} context, and with the {{Wiki|ambiguity}} involved in the very personal relationship between [[teacher]] and [[student]], especially when the [[teacher]] is a man and the [[student]] a woman or vice-versa. |

b) “No right no wrong”7 | b) “No right no wrong”7 | ||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

In the [[Zen]] and [[Tibetan]] [[traditions]], a [[teacher]] who has [[transmission]], meaning the full authorization to teach, is seen as a [[fully enlightened being]] in historical succession of the [[Buddha]]. Thus, the teacher’s {{Wiki|behavior}} is usually beyond question. However, this uncritical [[attitude]] has changed after the {{Wiki|sexual}} and financial scandals that troubled some American [[Buddhist]] centers in the 70’s and 80’s. On one hand, many students felt attracted to [[Buddhism]] precisely because they took as their guiding motto the [[Buddha’s]] parting words to his [[disciples]], encouraging them to be a [[lamp]] unto themselves, and not to [[trust]] any [[teachers]], teachings, or customs unless proven valid through their own [[experiences]]. On the other hand, they often accepted a teacher’s {{Wiki|behavior}} without question, believing that the [[enlightened]] {{Wiki|status}} somehow exempts the [[teacher]] from any [[objective]] standard of {{Wiki|behavior}}. A lifestyle involving misappropriation of funds, {{Wiki|luxury}} cars, frequently changing {{Wiki|sexual}} relationships with students and [[substance]] abuse would most likely be regarded as self-indulgent or {{Wiki|destructive}} in the case of anyone else, but in the case of an [[enlightened]] [[teacher]], these kinds of behaviors were somehow interpreted as an expression of self-realization.8 | In the [[Zen]] and [[Tibetan]] [[traditions]], a [[teacher]] who has [[transmission]], meaning the full authorization to teach, is seen as a [[fully enlightened being]] in historical succession of the [[Buddha]]. Thus, the teacher’s {{Wiki|behavior}} is usually beyond question. However, this uncritical [[attitude]] has changed after the {{Wiki|sexual}} and financial scandals that troubled some American [[Buddhist]] centers in the 70’s and 80’s. On one hand, many students felt attracted to [[Buddhism]] precisely because they took as their guiding motto the [[Buddha’s]] parting words to his [[disciples]], encouraging them to be a [[lamp]] unto themselves, and not to [[trust]] any [[teachers]], teachings, or customs unless proven valid through their own [[experiences]]. On the other hand, they often accepted a teacher’s {{Wiki|behavior}} without question, believing that the [[enlightened]] {{Wiki|status}} somehow exempts the [[teacher]] from any [[objective]] standard of {{Wiki|behavior}}. A lifestyle involving misappropriation of funds, {{Wiki|luxury}} cars, frequently changing {{Wiki|sexual}} relationships with students and [[substance]] abuse would most likely be regarded as self-indulgent or {{Wiki|destructive}} in the case of anyone else, but in the case of an [[enlightened]] [[teacher]], these kinds of behaviors were somehow interpreted as an expression of self-realization.8 | ||