5. The View of Mantra

This section has two parts: a proof of the view’s individual elements and a proof of the view in general.

1. Individual Elements of the View

This explanation proves purity, equality, and inseparability.

1. Purity

This section proves the principle of purity and disposes of claims that this principle is untenable.

The explanation of this principle involves proving

(1) appearances to be divine and

1. The Divinity of Appearances

This section consists of the actual proof of purity via the valid cognition that investigates the conventional and proof by the force of the valid cognition that investigates the ultimate.

1. Conventional Valid Cognition

There are a number of ways to prove the divinity of appearance in a way that accords with the experience of those who accept the existence of external objects. Here, however, I will simply off er an explanation of the essential points of this argument. The same body of water may appear to hungry ghosts as pus and blood, to humans as water, to those who dwell in pure realms as a stream of nectar, and to noble knowledge holders with pure vision as the form of

Māmakī. Touching it performs the function of moistening and pro- duces playful bliss and nonconceptual meditative absorption. For buddhas, who have completely exhausted all latent tendencies, nothing appears from the perspective of seeing things as they are, for all constructs without exception have been pacified.

From the perspective of seeing things in their multiplicity, however, appearances are seen as complete purity, the embodiment of limitless self-displayed domains of wisdom activity.

At this point, one may wonder which of these ways of seeing is valid, and which object is established in accordance with conventional reality. The purer the subject, the more valid its cognition. What a given subject sees can be established to be the natural state. This is similar to objects, such as a white conch

and yellow conch, and the minds that apprehend them. In this way, it follows that the natural state of all appearances can be proven to be the bodies and maṇḍalas of wisdom. The reason, here, is that their purity is perceived by noble beings who are free from distorting pollutants, just as a conch will be perceived to be white by someone with unimpaired vision.

Evidence of this can be established using both scripture and reasoning.

First, let us consider scripture as evidence. It is generally acknowledged in scripture that those who have attained the wisdom of transformation, such as those who dwell on the pure grounds, experience pure realms and other forms of pure perception. In light of this fact, one may argue that the noble ones see a

self-display, whereas that which is seen by ordinary beings is not seen as pure. If this were the case, however, it would absurdly follow that there are no objects of perception that can be shared by both pure and impure beings. Th is, however, is not the case.

Take the case of Śāriputra, who saw the Buddha’s realm as impure, and Brahmaśikhin, who saw it as pure. When they disputed, the Buddha made the pure realm visible to everybody and said: “Although my realm is always pure like this, you do not see it.” If authentic perception and mistaken perception were unable to

evaluate the nature of the same object, then whatever is seen by anyone would become valid cognition. In this way, one would be unable to tell the difference between the truth and falsity of the appearance of a yellow and white conch, respectively. Consequently, were any tradition to propose such a theory, all categories of validity and invalidity would vanish.

Therefore, apart from pure self-display, there are no impure objects. The Condensed Sūtra of Transcendent Knowledge states:

The purity of form should be known as the purity of fruition.

Pure fruition and form are pure in omniscience.

In omniscience, the purity of the fruition and the purity of form Are equal like the element of space—indivisible and inseparable. Objects are seen in a pure manner when the subject is purified of stains. In this way, the precise nature of the object becomes evident, like the perception that overturns the apprehension of a conch being yellow.

Second, let us consider evidence established through reasoning. The fact that the same object can be perceived in different ways is something that is clearly accepted and proven in this world, and if one has become accustomed to all phenomena being indivisible from the naturally pure basic space, one will only perceive appearances that are characterized by natural purity. This occurrence of consummate vivid appearance can be established through inference.

The basic argument is sound because as pure seeing is unmistaken, what- ever is seen in that mode must necessarily be in accordance with fact. If this were not so, pure seeing would have to be false and impure seeing would prove to be true. In that case, we would have to assert that the noble ones perceive erroneously and ordinary beings perceive correctly. What respectful and reasonable individuals would ever make such a claim?

In this way, the higher forms of perception refute lower ones, while lower ones do not invalidate higher ones. On this point, Entering the Middle Way states: The observation of someone with an eye-disorder Does not invalidate the cognition of one with healthy eyes. Likewise, a mind that lacks stainless wisdom Cannot invalidate a stainless mind.

Buddhas, who have completely purified all stains, see all that exists and, from this perspective, see all phenomena in a pure manner. Since this perception cannot be superseded, it is established as the final conventional mode of relative phenomena. In this way, it is of the utmost importance to understand that all these relative phenomena have two modes: the way they appear to confused perception and the natural state of the relative itself.

To believe that valid cognition that investigates the conventional is nothing but the confined perception of ordinary people, and that what is seen by that confined vision alone is the final natural state of the conventional is extremely closed-minded. When examined carefully, only a coarse intellect would see no reason to differentiate between the perception that a conch is white and the perception that a conch is yellow as, respectively, valid and invalid cognitions.

If the natural state of any given entity were nothing more than the way it appears to an ordinary being, then the appearance of a yellow conch to the one who perceives it as such would also be the conch’s true natural state.

One may think, “But such perception is distorted, insofar as it is caused by delusion; it is not a perception of the natural state.” Nevertheless, even though these impure appearances that are tainted by erroneous habitual conditioning are perceivable by ordinary people, one must assert that their natural state is the way they appear to pure beings, which are free from such stains.

Therefore, to give a brief account of this extremely profound key point, we will discuss the thoroughly conventional valid cognitions. Th ere are two such valid cognitions: the thoroughly conventional valid cognition based on con- fi ned vision and the thoroughly conventional valid cognition based on pure vision. In brief, the difference between these two can be explained in terms of their cause, essence, function, and result.

The valid cognition of confined vision is caused by a correct examination of its particular, limited object. In essence, it is a temporarily undeceiving awareness of merely its specific object. It functions to eliminate superimpositions regarding the objects of confined vision. It results in an engagement based on having fully determined the object at hand.

The valid cognition of pure seeing is caused by having correctly observed reality as it truly is. In essence, it is a vast knowledge concerning all possible subjects. It functions to eliminate superimpositions concerning a field of experience that the confined perception of ordinary beings cannot fathom. It results in the accomplishment of the wisdom that knows all there is.

These two valid cognitions can be likened to the human eye and the divine eye, respectively. The valid cognition of pure vision knows the object of confined vision, yet confined vision does not know the objects of the valid cognition of pure vision. The object of the latter is, therefore, unique.

Instances of this are the appearance of as many buddha-fields as there are dust motes in the world in a single dust mote, performing activities of many eons in a single moment, displaying emanations while not departing from the unchanging basic space of phenomena, and knowing all objects of cognition in a single instant with a nonconceptual mind.

These inconceivable experiences appear to conflict with the objects of ordinary confined vision. For this reason, this form of perception cannot be used to prove them. Yet this valid cognition can prove all of them as perfectly reasonable. The valid cognition of completely pure wisdom manifests by force of the reasoning of the inconceivable natural state. Therefore, it is extremely powerful, never deceptive, supramundane, pure, unexcelled, and unequaled.

All that can be commonly proven through the path of confined perception, such as proving the authenticity of our teacher, is established using the valid cognition of confined vision. The unique inconceivable experiences of the thus-gone ones, in contrast, are proven with the valid cognition of pure vision by

being in accord with the natural state. In this way, one should be knowledgeable concerning the essential point that profound principles, such as the primordial enlightenment of all phenomena, are not proven exclusively by means of confined perception, yet neither are they utterly without a valid means of proof.

Without knowing this, one will be unable to draw any qualitative distinctions between non attached non-Buddhists and the four sublime ones with respect to their ability to perceive sentient beings within the mere width of a chariot wheel, nor will one be able to note the difference between an erroneous cognition

that grows increasingly mistaken and a view that becomes increasingly sublime. There will also be no qualitative distinction made between the degree of knowledge possessed by those with different status, like the Buddha seeing the seed of liberation in the being of the householder Śrīsambhava, while the foe destroyers did not. In this way, one will not gain conviction in teachings, such as the following passage from a sūtra:

Even upon the tip of one hair There are an inconceivable number of buddha-fields.

Their various shapes are all distinct; They are clearly separate.

This issue is, therefore, of great import in both sūtra and mantra.

2. Purity and Ultimate Valid Cognition

The term “impure” refers to nothing more than the appearances that comprise the truths of suffering and its origin. The appearances that dwell in unity with basic space, which is empty of the two selves, can be established as neither the essence nor the object of disturbing emotions, such as grasping at a self, nor

can they be established as the identity of the karma and suffering that are produced by the disturbing emotions. Therefore, not even the names of the impurities contained within the truths of suffering and its origin exist.

Everything dwells naturally in a state of purity.

Therefore, since there is no phenomenon that is not of the nature of the great equality of emptiness, all of appearance and existence is proven to be primordial great purity. The principle of purity is not simply expressed from the perspective of emptiness, in which no phenomena exist. Rather, because

appearances themselves are inseparable from emptiness, they are shown to be great bliss, exactly in the way they appear. They are always sublime and primordially pure.

Great purity can be proven in the following way to philosophers who do not accept any shared external object of perception, and who instead assert that all phenomena are merely the mind’s own display. First there is an occasion of impurity, in which various appearances of the six classes are perceived. As the mind

conceives in various dualistic ways, they appear through the fully developed force of solidifying habitual patterns. Pure appearances manifest in the context of the path free from error, while the boundless appearances of complete purity manifest in the context of the fruition, at which point the entire range of obscurations have been exhausted.

All of these appearances are none other than the self-display of one’s own mind. While functioning as the basis for all of them, however, the mind is luminous and empty of the two selves. It dwells as the unobstructed manifestation of various appearances. When the mind’s apprehensions are out of touch with the way things are, it apprehends a self, as well as subject and object, thereby producing disturbing emotions that, in turn, create karma.

As a result of this, all the various appearances that are subsumed under the truth of suffering can manifest, just like appearances in a dream. All of these confused experiences are not grounded in reality; they are unreliable and deceptive.

By training on the path in accordance with the mind’s natural state, the confused aspect of self-display will gradually be reversed. When this happens, pure appearances will faultlessly dawn and will no longer revert back.

As these appearances are undeceiving and in tune with reality, they appear faultlessly as mere conventional self-display. Th us, confused appearances are not true, while pure appearances are true, insofar as they are free of stains.

For instance, if one blends the element of gold that comes from earth and metal with the likes of the finest gold and the element of quicksilver, which comes from coal, water, and herbal ingredients, it will come to resemble a single mass, like a glob of fresh butter. As the object of sense-faculties like the eye, these ingredients will not be evident, while one may still understand it to possess various ingredients as an object of the mind. Confused individuals will

perceive it to be a mass of butter or grease. Others will see it as a cause of gold, with the mere understanding that it will become gold once burned. Learned individuals, on the other hand, will see that it possesses various constituents and will perceive its ability to appear in various ways depending upon the various conditions it meets with. When such a mass is cold, it will remain like a mass of fresh butter for an extremely long time. When it touches a flame

and heats up, however, it will become the color of copper, bronze, and brass. Likewise, when heated with a strong flame, it will become the nature of ordinary gold, and will become the nature of the finest gold when heated thoroughly. From that point on, it will not change in nature, no matter what temperature its surroundings are.

The all-ground consciousness can be understood in a similar fashion. The all-ground, the container of all seeds, manifests as the entire range of appearances. In the same way that a mass can appear differently to those of various faculties, the all-ground may appear in specific contexts as environs, bodies, and objective experiences that are either pure, impure, or completely pure.

Just as one may understand the mass to possess various ingredients, the mental consciousness realizes that the seeds for an infinite range of appearances throughout time and space are present within the all-ground, regardless of whether or not they have actually manifested from the all-ground.

In the same way that the mass may be confused for a chunk of butter, some may apprehend all the appearances of the all-ground as a self and phenom- ena. Moreover, just as some may perceive the mass as quicksilver, some people apprehend the aggregates as suffering, being characterized by the ripening of karma.

Similar to apprehending the mass to be the cause of gold, some perceive the aggregates themselves as the cause for the completely pure bodies and experiences of those who live in the pure realms. Learned individuals understand that, although the mass itself is not gold, it is not without the nature of gold either. Although it appears to be quicksilver, it is not the case that the gold transformed into quicksilver, nor is it the case that it lacks the nature of

quicksilver. Such individuals will say that the nature of quicksilver is unstable and that it is easy for it to transform into a variety of things. They know that the nature of gold is much more stable, for it is difficult to trans- form and will not diminish in quality. Even when burned in a blazing fire, it will not be readily depleted.

Likewise, impure phenomena are unstable and extremely deceptive. The appearances of past and future lives are mutable and exhausted by cultivating the path. Pure appearances, however, are the exact opposite. As soon as one has mastered a pure body and experience, one will never have to experience impurity again. One will develop supreme bliss, which is completely pure and free from suffering. In this way, pure appearances are reliable and undeceiving.

Therefore, when compared with other perceptions, the mass with various constituents will truly become the nature of gold. Likewise, the all-ground, endowed as it is with various potentials and appearances, truly is the domain of pure appearances. When all the temporary habitual patterns related to delusion have run

out, they will produce no more appearances. Nevertheless, the spontaneously present appearances of unobstructed natural radiance that occur within primordial basic space cannot possibly be retracted since they are essentially inseparable from it. Therefore, pure self-displays of stainless wisdom are pure in actuality.

In this way, if the identity of all saṃsāric phenomena is proven to be the pure deity, one may wonder what this term actually means. The actual deity of reality itself is the wisdom of nondual appearance and emptiness. It is the vajra body free from the obscurations of transference. It is the enlightenment of equal taste, where even the most subtle habitual tendency to obscure the reality of suchness has run out. It is inconceivable, free from the confnes of

singularity and multiplicity. Although beyond the entire realm of characteristics, it manifests in the form of all that can be known. It is the body of self- occurring wisdom, which is without difference and distinction from all the bliss-gone ones of the three times. It is enlightenment as the equality of all of saṃsāra and nirvāṇa. Th is is the ultimate deity, the universal master of all buddha families.

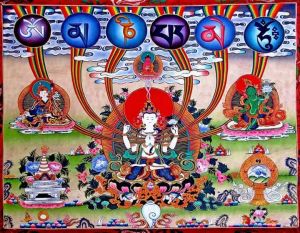

The subject, the symbolic deity, manifests in the symbolic form of the wisdom body itself, which transcends the domain of signs. As taught in each individual tantra, they appear in peaceful and wrathful forms with attributes like faces and hands, as main deities and their retinues, and as the support and supported.

Therefore, since all phenomena are of the same character within the expanse of the equality of appearance and emptiness, they are pure in being the essence of the main deity within the maṇḍala of the one with the body of vajra wisdom. Alternatively, since body, speech, and mind are the three vajras in nature, they are pure in being the three buddha families, while the five aggregates are pure as the five buddha families. In this way, phenomena can be classified into five

or one hundred buddha families, all the way up to the inconceivable families of the magical net. The rationale here is that one can make as many divisions of purity as there are appearances of impurity, and that there is not even a single phenomenon whose essence wavers from the natural state of great purity and equality.

Reality is nothing whatsoever, yet from it, anything can arise. Due to this key point, its self-display manifests impartially and without limitation as the display of the magical net. Therefore, while the innumerable buddhas and their buddha-fields are completely pure, any amount of classification can be

accommodated, no matter what distinctions are being made. Th e reason is that no phenomenon is beyond the identity of self-occurring wisdom, great purity and equality, the reality beyond one and many. Hence, purity is contextualized in various ways in the various classes of tantra, according to the enumeration of

their respective deities. Th e Tantra of the Secret Essence also teaches the principle of great purity in the following lines: Th e world, beings, and continua are realized to be pure.

And:

The secret bindu is the basic space of the maṇḍala.

The elements are knowledge, the mother of the families.

The great ones are the suchness of the families.

The awakened mind is the vajra assembly, As are the faculties, objects, time, and awareness, Seen in the maṇḍala of Samantabhadra By the five wisdoms of the enlightened mind Of the superior illustrious being.

Other tantras teach this as well. The Hevajra Tantra, for instance, explains: Sentient beings are actual buddhas, Yet obscured by temporary stains.

While the Wheel of Time states: Sentient beings are buddhas.

Th ere are no other illustrious buddhas in this world.

In the Conduct Tantra of the Yoginī, it is said:

The identity of all these beings is that of the five buddhas.

They appear just like dancers or superb paintings.

That which is called “great bliss” is singularity, Manifesting dances of plurality within the experience of singularity.

And the Heruka Galpo states: Through the causal vehicle of characteristics, Sentient beings are understood to be the cause of buddhas.

Yet the fruitional vehicle of mantra Meditates on mind itself as buddha.

Furthermore, according to the common great vehicle, it is also taught that all phenomena are in all ways fully and truly enlightened.

2. Relinquishing the Untenability of Purity

This section contains both a general and a specific way to refute critiques of purity. First, concerning the general refutation, some narrow-minded

individuals may object that meditating on the world and its inhabitants on the path may merely cause them to appear to be pure, although this is not actually the case. The reason given is that while they may appear in this manner, their nature is of the truths of suffering and its origin.

We also accept that those of us with impure minds and impure eyes perceive things in an impure manner. Nonetheless, if everyone experienced pure appearances, what would there be to argue about? Although things may appear in an impure manner, this is not how they actually are. In fact, in their natural state, they

are naturally pure. If one makes such an assertion, appearances do not necessarily have to appear the way they truly are because they can appear incorrectly to a mind tainted by confusion. This is no different than an eye cognition that perceives a snow mountain to be blue.

This is explained in the Root Knowledge of the Middle Way:

If an objection is made through emptiness, Whatever may be replied Will not be a reply, But the same as what is yet to be proven.

For instance, when resolving all phenomena to be empty, no matter what phenomenon is posited to prove that things are not empty—including the causality of karma, saṃsāra, and nirvāṇa—the proof will amount to the same as what is still to be proven, and so one can prove that also the proof itself lacks inherent existence. Hence, whatever is set forth to prove that things are not empty becomes an aid to the reasoning that establishes emptiness, just like adding fuel to

fire. Just as one will be unable to find a reasoning that dis- proves emptiness, any proof that is put forward to establish that phenomena are impure will itself be shown to be purity. Therefore, no matter where one searches, one will not succeed in finding an argument that can disprove the reasoning that establishes all phenomena to be pure in their natural state.

When using great purity in an argument, Whatever may be replied Will not be a reply, But the same as what is yet to be proven. Furthermore, if sentient beings are buddhas, would it not follow that buddhas suffer when sentient beings are miserable in hell? Th e answer is no.

The misery in hell is merely apparent to the confused perception of those who have not realized the natural state. From the perspective of the way things appear, they are not buddhas. Therefore, this objection does not hold.

There is no such thing as suffering in the natural state. The Elaborate Magical Net says:

Without the self-awareness of authentic knowing, Even the realms of the bliss-gone ones are seen as the lower realms.

If one realizes the meaning of the equality of the supreme vehicle, These hellish abodes themselves are the abodes of the unexcelled and joyous. Some may infer other absurd consequences as well, such as saying that if all phenomena are primordially enlightened by their very nature, they should be

universally perceived as such and there would be no need for cultivating the path. This attitude is pitifully small-minded. Claiming this would be tantamount to saying that a white conch should be perceived as such by even a visually impaired individual, and that there would be no need to try to heal such an impairment.

Therefore, when things do not appear the way they truly are, it is because the stains of confusion cause this to happen. Hence the path must be cultivated to counter confusion. Although the nature of all phenomena is emptiness, one must practice the path for it to be actualized.

Consequently, any attempt to refute great equality is dispensed with in a way similar to the response to refutations of emptiness. When applying reasoning, both purity and equality are mutually confirming and of a single key point. Since both are the nature of things, the proof of great purity is an extremely forceful reasoning arrived at through the power of fact. As such, it reigns supreme and cannot be invalidated.

Second, concerning the specific refutation, some may object that, even though purity can be proven in this way, if a buddha’s wisdom only sees everything as pure, the objects and subjects appearing to the perception of confused beings will not be observed. Consequently, if they were not seen, a buddha would not be omniscient. Yet if they were, a buddha would see impure phenomena.

The wisdom of omniscience allows buddhas to know appearances in the way they appear, even those that appear to be impure. Still, it is not that these impure appearances truly exist, or that buddhas perceive phenomena that are proven to be impure. Buddhas see clearly how objects seem to be true to those who cling to

true existence, likewise they see how the subject fixates on their true existence. Nevertheless, a buddha will not view any phenomenon as truly existent because it is impossible for such a being to see even the tiniest particle as truly established. In this way, since buddhas perceive all phenom- ena as a self-display, it can be proven that buddhas only perceive purity.

2. Equality

This topic has two subdivisions: arguments that prove equality and how to gain certainty about this principle.

1. Arguments for Equality

If the phenomena of saṃsāra and nirvāṇa are properly examined with the logical arguments of the Middle Way, such as the one from lack of one and many, one will gain certainty that not even a subtle particle of any given entity is truly established. This holds not only for the impure phenomena of saṃsāra, but also the pure bodies and wisdoms.

2. Gaining Certainty about Equality

There may be people of sharp faculties who will analyze the mind in terms of its arising, abiding, and cessation, and thereby come to experience the nature of the three gates of liberation: emptiness of cause, effect, and essence. Th is alone will lead to an instantaneous certainty in the meaning of the equality of appearance and emptiness.

However, in terms of ascertaining equality in a gradual way, beginners should begin by correctly examining the reasons that prove emptiness, such as the logical analysis of investigating singularity and multiplicity. When one reflects on the meaning of nonexistence at that time, in relation to a vase, for

instance, one will find that although things seem to exist when not investigated, nothing can be found upon analysis. Thereby, one will come to believe that nonexistence itself is the natural state. Thus, an image of emptiness manifests in a process of alternation between appearance and emptiness.

When at that time one reflects on the way that this nonexistence of phenomena is also just a mere imputation and not actually established, or on the way things appear while being primordially empty, one will develop an extraordinary certainty about phenomena being empty while apparent, and apparent while empty, like

the moon’s reflection in a pool of water. At that time, the absence of nature and dependent arising will dawn in a non contradictory manner. This is referred to as “the understanding of unity.” Although “absence of nature” and “dependent origination” are different expressions, here one gains certainty that these two are essentially inseparable and with- out the slightest difference.

Through this, the conceptual thought that connects appearance, the basis for negation, with an eliminated object of negation naturally falls away. In this way, the characteristics of freedom from constructs, such as the ability to remain naturally without negation and affirmation, adding and removing, will dawn. As one grows increasingly familiar with this freedom from constructs, the entirety of dualistic phenomena, in which a confined mind observes particular intrinsic natures in relation to individual subjects, becomes purified.

This process reaches a point of culmination by bringing forth a distinctive certainty that the nature of all phenomena is one of equality.

In this way, one first understands emptiness, then unity, freedom from constructs, and, fi nally, equality. By understanding the former one gains access to the latter. However, until one has gained certainty in a preceding principle, one will not be able to resolve the subsequent stage. Submitting oneself to the idea

that the categorized ultimate, the mere lack of true existence, is the natural state will not bring one even close to the equality that is demonstrated in this context.

Merely understanding the contradistinction that is the elimination of true existence, thinking this exists with reference to pillars, vases, and other such things, will not perform the function of equality, which is to do away with all notions of phenomena bearing marks and having good and bad qualities.

Just so, a commoner cannot perform the duties of a king. Therefore, when perfecting the Middle Way path free from all constructs, all phenomena are seen to be equality. This is the realization of great equality referred to in this context. On this point, the Tantra of the Secret Essence says: Not understanding freedom from reference points, You do not comprehend the basic space of phenomena.

Therefore, destroy entities and nonentities And thus apprehend freedom from reference points!

And also:

Through the two equalities and the two superior equalities, There is the realm of the Samantabhadra maṇḍala.

Not only do the tantras teach this, but the common vehicle as well. For instance, the Sūtra Requested by Kāśyapa mentions:

Kāśyapa, realizing all phenomena to be equality is nirvāṇa. Th is is one, not two and not three.

This explanation also demonstrates that ultimately there is only one vehicle.

The Sūtra That Shows the Way to Awakening explains:

Mañjuśrī, whoever sees that all phenomena are equal, nondual, and inseparable possesses the authentic view.

3. Inseparability

Purity is established from the perspective of appearance, and equality from the perspective of emptiness. Since these two are inseparable and of one taste within all phenomena, the inseparability of purity and equality is proven indirectly through each of these principles. Whatever appears in a pure man- ner is

empty of all extremes; and whatever is equality, meaning free from all extremes, manifests as the extreme purity of the manifold appearances of the magical net. These two are inseparable within the single sphere of the dharma body. This is what the individual self-awareness of the sacred ones realizes and this is the manner of the great perfection of unity. On this point, the Tantra of the Secret Essence states:

In the secret bindu, the basic space of suchness, Is the actuality of all the buddhas.

One sees the very face of the embodiment of enlightened body, Speech, qualities, activities, and mind, without exception, Of the completely perfect ones in the ten directions and four times.

Th is mastery is the most sacred and supreme.

And:

Self-occurring wisdom appears without abiding.

As for the way to practice this, it is said: Emptiness, the absence of self, is primordially known by self-awareness, the enlightened mind.

With nothing to observe and nothing observing, mindfulness brings mastery.

The amazing enlightened body, speech, qualities, and buddha fields, Are nowhere else; rather, it itself is just like this.

The Compendium of Vajra Wisdom states:

Were the two truths separate, The path of wisdom would be pointless.

If clarity and emptiness were separate, One would fall into the extremes of eternalism and nihilism.

And:

Since the essence of all phenomena is beyond a path, By perfecting it you are freed from eff ort and strain.

The completely pure innate wisdom, Is a non abiding unity.

The Nondual Victory likewise explains: Since they are profound, vast and inseparable, Appearance and emptiness are inseparably mixed.

This is taught to be the buddha And demonstrates the principle of enlightenment.

While the Vajra Garland Tantra states:

The relative and the ultimate, When free of these two concepts, They are completely integrated.

This is explained to be “unity.”

2. General Explanations

Th is explanation has two subdivisions: establishing the present meaning directly to fortunate individuals and indirectly to skeptics.

1. Directly Establishing the Meaning

Th e meaning of the inseparability of purity and equality, which is beyond the intellect, is established by means of four realizations:

1) In the equality of the basic space of phenomena, all phenomena are established to be of a single cause, or a single mode.

2) The apparent aspect of this equality is the wisdoms and bodies. These are established through the principle of the seed syllable, as various syllables can manifest from certain conditions, such as the single sound of the syllable “A.”

3) The single cause and the principle of syllables mutually bless each other and are beyond meeting and parting.

4) In this way, the meaning of the great dharma body, the inseparability of purity and equality, is experienced through one’s own self-awareness in a way that transcends the intellect.

As an alternative to this gradual explanation:

1) In the essence of the inseparability of the truths of purity and equality, all phenomena are of a single taste and a single cause.

2) This is exemplified by the syllable OṂ, which is illustrated by the three syllables A, U and M. These three, in turn, demonstrate the inseparable nature of enlightened body, speech, and mind, and of the three gates to complete liberation.

3) By the force, or blessing, of these two arguments of meaning and metaphor, all phenomena are resolved to be primordially enlightened as great purity and equality.

4) Although this meaning can be proven to be in accord with scripture and key instructions, it is not resolved through speculations that merely rely on the words of the scriptures and key instructions. The view of mantra is resolved from the depth of one‘s heart through the four direct ways of gaining certainty.

Here, unity is pointed out from the very beginning, so explanation pertains to the instantaneous type. Still, in both cases, the four reasons, such as that of the single cause, are undeceiving means for accessing the profound view of mantra. Therefore, they are called “arguments.”

2. Indirectly Establishing the Meaning

The meaning of the primordial enlightenment of all phenomena is extremely difficult to comprehend. For this reason, some individuals will find it implausible. To such people, one can explain the meaning indirectly in the following manner. First, while non-Buddhists are doubtful of the idea that Buddha is an authentic being, in the Vedic scriptures, which they themselves believe in, it is said:

On occasions as rare as the occurrence of an udumbāra flower, an omniscient teacher appears in this world in the ruling or priestly caste. When entering the womb, his mother dreams that he enters in the form of an elephant. When born, he displays major and minor marks. If he does not renounce the world, he will become a universal monarch; if he does, he will become enlightened.

In this way, such scriptures establish the existence of the Buddha.

From a logical perspective, the path shown by the Buddha, such as the absence of personal self, can be proven to be a liberating path through the reasoning of the power of fact. Moreover, as this is the case, the Buddha can be proven to be an authentic teacher for anyone who seeks liberation, and the path that he taught can be proven to be authentic. In establishing our teacher’s authenticity, the chapter “Establishing Validity” and other sources prove just this.

Though listeners believe in the existence of the Buddha, they do not believe in the emptiness taught in the great vehicle. As for scripture, however, their own lesser vehicle sūtras make statements such as “form is like a mass of foam.” Moreover, from a logical point of view, if one fails to see the five aggregates’ lack of true existence, insofar as they are composite and momentary, one will not establish the absence of personal self. Therefore, just as the Jewel Garland explains, it can be proven that liberation is accomplished based on emptiness.

There are also scriptural and logical defenses directed toward those follow- ers of the sūtra path who do not believe in the profound view and conduct

of secret mantra. In terms of scripture, the Royal Sūtra of Bestowing Instructions prophesizes the later appearance of mantra. Moreover, the Sūtra of the Ornamental Array explains the five aggregates to be of the nature of the thus- gone ones:

Whoever dwells in the equal nature Of oneself and the buddhas, Does not abide or appropriate; He or she is a thus-gone one.

Form, feeling, perception, Consciousness, and intention Are the countless thus-gone ones; They are the great sage.

The Vimalakīrti Sūtra says:

Disturbing emotions are the lineage of the thus-gone ones.

And:

The teaching that freedom from desire and other such factors is liberation is taught for arrogant individuals; the liberation of selfless individuals is taught to be the nature of desire and other such factors.

Moreover, afflictive emotions themselves are taught to be wisdom in certain scriptures, such as the Sūtra of Mañjuśrī’s Display, which says: Disturbing emotions are the vajra bases of awakening.

For instance, the Sūtra of the Emanations of Mañjuśrī says:

Nirvāṇa is not something that is cultivated through abandoning saṃsāra. Instead, nirvāṇa is to observe saṃsāra itself.

This shows that saṃsāra is enlightenment. Also, the Avataṃsakasūtra states:

Though numerous worlds may burn In the most inconceivable ways, Space will not disintegrate.

Such is the case with self-occurring wisdom.

Citations such as this teach self-occurring wisdom. Moreover, the sūtras teach that all sentient beings possess the core of self-occurring wisdom. There are also countless statements that explain how, although Buddha Śākyamuni’s realm is always pure, it is not seen as such. There are even statements in sūtras about

pleasing the Buddha with a woman’s body: A Bodhisattva should transform his own body into a female body in order to please the Th us-Gone One and then always remain before the Thus-Gone One.

Th ere are also many statements that teach how to compassionately annihilate people, such as those who harm the dharma.

Regardless of whether the situation calls for scriptural citations, such as the one just mentioned, or logical analysis, all phenomena—as they appear—are naturally purity and equality. Therefore, they are not established as saṃsāra and nirvāṇa, good and evil, or in terms of rejection and acceptance. As was

explained before, secret mantra is proven to be the supreme vehicle. It is certain that from the moment you accept emptiness, purity can also gradually be established.

Again, there may be some for whom most of the mantra explanations make sense, but for whom the meaning of the actionless great perfection seems unreasonable. On this issue, scripturally, the unsurpassable tantras teach that sentient beings are of the identity of enlightenment, and that the aggregates, elements, and other such factors are pure in the sense of being divine.

These scriptures also prove how one does not truly need to rely on activities involving maṇḍalas, tormas, and so on. They also point out the wisdom in the fourth empowerment.

Reasoning establishes the world and its inhabitants to be a primordial purity and equality. Therefore, one does not need to accomplish these factors anew through the path. For people who have realized this in the core of their hearts, a regimen of effortful pursuits is proven to be a great obstacle

to the path. Hence, it can easily be established how the practice of uncontrived naturalness allows one to attain mastery over the self-display of wisdom appearances.

In this way, subsequent points will not be established unless the points that precede them are proven as well. In teaching a sequence of vehicles that are like the rungs of a ladder, the Buddha showed how to cleanse the jewel of the basic potential. If one were to explain the profound secret to narrow- minded people who have yet to gain confidence in more basic topics, they will give it up or disparage it out of fear. Therefore, these instructions are extremely secret.

If, on the other hand, the profound realization of the view of the unsurpassable mantra is taught to those who have gained confidence in the meaning of great equality as explained in the sūtra vehicle, it will make sense to them. Therefore, being well versed in all the gradual vehicles will enable one to establish the final philosophy of the vajra pinnacle. Though endless when examined in detail, these explanations are meant to be a mere gateway into reasoning.

4. Purpose

The view serves both a both a general and a specif c purpose.

1. General Purpose

While on the path, all practices are accessed according to one’s own personal view. This is the nature of things. Thus, all practices of the vajra vehicle are exclusively practiced according to one’s understanding of the principles of purity and equality. This view is like the capacity to see. Without it, awareness

and “legs” will be missing as well. In this way, meditation and other such factors of the path will be a mere facade. On the other hand, any practice that is imbued with an authentic view such as this will become the true path of the vajra vehicle. As the key point of all paths comes down to this alone, it is of paramount importance.

2. Specific Purpose

Everything unfolds through the force of the view: meditation becomes unmistaken, conduct meaningful, the maṇḍala accords with reality, and the attainment comes through the bestowal of empowerment. Likewise, it

becomes difficult to transgress the samayas, the practice will not be squandered, offerings become completely pure, mastery is gained over enlightened activity, and mudrās and mantras become sublime.

If all phenomena were not purity and equality, meditating on the divine nature of the world and its inhabitants, the support and the supported, would be a form of training that conflicted with reality and one’s meditation would be mistaken. However, since one is meditating on the way things are, this is not the case and the practice is not mistaken.

Th e same goes for conduct. If there is purity and equality, it is reasonable to engage in actions that accord with the view, such as the disciplined conduct of freely enjoying sense pleasures, being free from accepting and rejecting, and engaging in union and liberation. Were this not the case, it would be true

that these are all to be abandoned, as is stated in the common vehicles, and engaging in them would be immoral. Therefore, it is due to the essential point of purity and equality that these mantric practices become meaningful.

Regarding the maṇḍala, the natural maṇḍala of the inseparable ground and fruition is represented by the symbolic maṇḍala and the maṇḍala of the path. Th e fruitional maṇḍala appears due to the path. However, if the ground were not like this, the path would not be authentic either, and no pure fruition could appear from it. By resolving the ground exactly as it is, the maṇḍala accords with reality.

As for empowerment, one’s own body, speech, and mind, along with their equal aspects, dwell primordially as the four vajras. This is to be understood, experienced, and realized through the power of the empowerment, just like a vase seen with the help of a lamp or the moon pointed out by a finger. Apart from this nature, there is no meaning to be pointed out through the empowerment. Thus, the attainments derived from empowerment likewise depend on the view.

In terms of the samayas of mantra, it is said that one should not doubt the explanations that all phenomena are naturally pure as the deity, nor should one conceptualize equality, which lies beyond names and other such factors, by identifying it with characteristics. If all phenomena were not purity and equality,

whoever perceived them to lack these qualities would be in accord with reality and, thus, would not be committing a root downfall of mantra. Ths would also not accord with teachings given in the context of the path of freedom from desire.

Moreover, the samayas of conduct, such as not mortifying the aggregates and joyfully accepting sense pleasures, samaya substances, and mudrās are in accord with purity and equality. Were this not the case, they would truly be as explained in the lower vehicles. It would, therefore, not make sense that one would commit a root downfall by abandoning something that ought to be rejected.

Therefore, one would be free to transgress the pledges of mantra. However, due to the essential point that everything is pure and equal, the samayas should definitely not be transgressed by turning away from the view and the actions that are played out from that view. Consequently, the samayas are hard to transgress.

In practice, the deity is inseparable from the aggregates, elements, and sense sources. If this is their natural state, then it makes sense to actualize this state as it is by practicing the path. Were this not the case, however, it would be like trying to wash charcoal white or meditating that mind is matter . . .

no matter how much one were to try, there would be no change. Since it would then become impossible to accomplish the deity’s indivisibility, one’s practice would be squandered. However, through the key point of purity and equality, practice is not wasted in this manner.

As for making offerings, the five types of meat, the five nectars and other substances that the world considers dirty are used as principal offerings in mantra. If they were actually impure, offering them to the deities would not be a viable option. Still, one may believe that blessing them with mantras and mūdras makes them pure. If this were the case, then it would make better sense to off er pure things and bless them with mantras and mūdras.

What special purpose would there be in offering impure things? Therefore, although it is fine to practice cleanliness as taught in action tantra, in this context the five nectars and other substances should be utilized to dismantle the notions of pure / impure and acceptance/rejection. Since these substances also manifest through the key point of natural purity and equality, they are completely pure as offerings.

Regarding enlightened activity, according to inner mantra one imagines oneself to be primordially indivisible from the enlightened body, speech, and mind of the thus-gone ones, and one practices specific activities thereby.

These activities become supremely powerful, matching the enlightened deeds of the thus-gone ones. If one were not essentially divine from the beginning, mentally fabricating something that does not accord with reality would not accomplish anything of superior value. However, since everyone is of the nature of

great purity and equality, we are all inseparable from the deity in reality. Since the practices of inner mantra are superior to the approach of action tantra and other systems, one is able to gain mastery over the activities of enlightenment.

Mantra and mūdra are more powerful than the locks and recitations of outer mantra. This superiority is due to the force of maintaining the practice of habituating oneself to the realization of one’s own indivisibility from the deity. If they did not accord with reality, then reciting mantras and performing

mudrās as outlined in the inner mantras would not by nature hold greater blessings than reciting the Buddha’s dhāraṇī. However, the mantras and mūdras that are connected to the development and completion stages of unsurpassable mantra possess the perfect power of great blessings, for they are accomplished through the ability to unerringly engage with the meaning of great purity and equality.

Therefore, as the actual nature of things, great purity and equality are the objects one must resolve through the view. This key point establishes the meditations and other practices of mantra to be of an unmistaken nature and constituting a delightful and swift path. Through the view that realizes the meaning of purity and equality, one arrives at supreme confidence in all paths of mantra. With this confidence, all paths embraced by this view become authentic paths of mantra.

This concludes the brief explanation of the view of perfect knowledge, the first parameter in secret mantra.

2. Absorption

Absorption will be presented in terms of its

(1) essence,

(2) divisions,

(3) practice, and

(4) purpose.

1. Essence

Whoever tames the crazed elephant of the mind By placing it in equanimity And fully relies on mantra and mudrā Will reap a great and wonderful spiritual attainment.

As this verse explains, the Sanskrit word samādhi means a balanced mind.

It means to train the mind such that one is able to rest one-pointedly on an observed object. It can also mean to rest in accordance with, or in the

same manner as, an object undisturbed by dullness, agitation, and other such factors.

2. Divisions

This topic has two divisions:

(1) essential divisions and

(2) temporal divisions.

1. Essential Divisions

Th eessential division concerns the absorptions of development and completion. Development stage meditation has four divisions, each of which purifies the predispositions related to one of the four types of birth. The elaborate version consists of making others one’s own children, becoming the child of others, developing the five manifestations of enlightenment, and developing the fourfold vajra ritual. The medium-length version makes use of a threefold development

ritual. In the condensed version, which is employed in anuyoga, the mere recitation of mantra triggers the visualization. In the extremely condensed version, as found in atiyoga, one completes the process of development in an instant of recollection.

Alternatively, in conformity with womb birth and miraculous birth, a dual division of the development stage into gradual and instantaneous approaches is also taught. Moreover, there is also a fivefold distinction that follows the five gradual practices, such as that of great emptiness. There are, in fact, a great number of other divisions, such as the absorptions that observe the meaning of the four seals of enlightened body, speech, mind, and activity. In actuality,

however, all practices that are classified as development stage are termed “development stage absorptions.” The completion stage consists of the path of means and the path of liberation. The former may rely upon the upper and lower gates, while the latter consists of the gradual and instantaneous nonconceptual practices of unity.

2. Temporal Divisions

Absorption can be divided temporally into blessed practice, imputed practice, and perfect practice. The ultimate deity is indivisible basic space and wisdom. Through its power, the symbolic deity of the form body appears. If one visualizes such a deity, one’s own essential nature will be blessed by the essential nature of the deity.

First, as one meditates on the deity, one trains devotedly with the knowledge that this process is like pouring an alchemical elixir on iron. Second, one trains to become competent with the understanding that the form body is produced from the pure awakened mind, just as one creates a statue from melted gold. Th ird, a practitioner who has realized his or her nature to be pure perfects the absorption instantaneously, just like a reflection clearly appearing in a limpid pond.

As the Magical Net of Vairocana mentions, these three trainings embody, not only the entirety of mantra, but also the vehicle of characteristics belonging to the listeners, Mind Only, and the Middle Way.

3. The Practice of Meditative Absorption

Not only are the calm abiding meditations that are based on the unique methods of mantra deeply meaningful and easy to practice, the way they are practiced is also common to the sūtra approach. In both cases, one must gain the stability of a pliant mind and then proceed to develop it in a progressive manner.

Moreover, by relying on the eight formative mental states that dispel the five flaws, one uses the six powers to meditate step-by-step on the nine methods for resting the mind. Th is takes place within the context of the four types of attention, allowing one to gradually produce the five experiences of meditative concentration and, thereby, accomplish the pliancy of calm abiding.

The Five Flaws

Th e five flaws that inhibit meditative concentration are

(1) laziness,

(2) forgetting the instructions,

(4) failure to apply their antidotes, and

(5) applying these antidotes even though one is not dull or agitated. Of these, the first two prevent the initial stages of entering absorption, the third hinders the main practice of absorption, and the last two prevent absorption from deepening.

The Eight Remedies

There are eight remedies that dispel these flaws:

(1) faith,

(2) yearning,

(3) exertion,

(4) proficiency,

(5) mindfulness,

(6) introspection,

(7) attention, and

(8) equanimity.

The first four dispel laziness. Faith in the attainment of absorption produces yearning and sincere interest. This, in turn, spurs one to exert oneself, and one thereby becomes proficient and abandons laziness.

Mindfulness ensures that the instructions are not forgotten, while introspection allows one to notice when dullness and agitation occur. When they do, attention enables one to apply their respective antidotes. As dullness and agitation subside, one rests in equanimity without forming any concepts. In this way, these eight factors remedy forgetting the instructions and the rest of the faults in a progressive manner.

The Six Powers

Six powers are required to practice absorption in this manner:

(1) study,

(2) contemplation,

(3) mindfulness,

(4) introspection,

(5) diligence, and

(6) complete familiarity.

These powers should gradually accomplish the nine methods for resting the mind within the context of the four types of attention.

The Four Types of Attention

The four types of attention are:

(1) concentrated attention,

(2) occasional attention,

(3) uninterrupted attention, and

(4) effortless attention.

The Nine Methods for Resting the Mind

The nine methods for resting the mind are:

(1) settling,

(2) continuous settling,

(3) resettling,

(4) completely settling,

(5) taming,

(6) pacifying,

(7) completely pacifying,

(8) attentiveness, and

(9) equipoise.

These nine are mentioned in a sūtra, which states, “settling, genuinely settling, collecting and settling, thoroughly settling, taming, pacifying, thoroughly pacifying, one-pointed, and absorbed.”

To elaborate, study leads to settling; contemplation to continuous settling; mindfulness to resettling and completely settling; introspection to taming and pacifying; diligence to completely pacifying and one-pointedness; and complete familiarity leads to equipoise.

In this regard, the first attention relates to the occasion of the first two mental states; the second attention to the third to seventh; the third attention to the eighth; and the fourth to the ninth.

These nine states are also said to unfold by way of five experiences. First is the experience of movement, which is like a cascading waterfall. Second is the experience of attainment, which is like a river gushing through a gorge.

Third is the experience of familiarity, which is like the flow of a large river. Fourth is the experience of stability, which is like a wave-free ocean. Fifth is the experience of completion, which is like a mountain.

Next I will offer practical key instructions that accord with the essential points of these principles.