The True Origins of Psychology and the Influence of Euro-American Ethnocentrism by Robert Espiau

The True Origins of Psychology and the Influence of

Euro-American Ethnocentrism

by

Robert Espiau

30 December 2013

© 2013 Robert Espiau

All rights reserved

Contents

- 1 Abstract

- 2 Dedication

- 3 Chapter IIntroduction

- 4 Chapter IILiterature Review

- 4.1 Introduction

- 4.2 The Ethnocentric History of Psychology

- 4.3 Psychology Originated in India, not in Greece

- 4.4 Importing Psychoanalysis to India

- 4.5 Brief Background of the Schools of Teaching Within Buddhist Psychology

- 4.6 Non-Western Models of Self That Have Been Discounted and Overlooked

- 4.7 Structural Examples of Psychological Theories Taught by Buddha

- 4.8 Summary

- 5 Chapter IIIComparative Analysis: Decolonizing Buddhist Practice

- 5.1 Introduction

- 5.2 Buddhist Meditation Practice: Learning to Know Without the Intellect

- 5.3 The Foundations of Buddhist Meditation: Samatha and Vipassana

- 5.3.1 Jhana meditation: right concentration

- 5.3.2 The eight jhanas

- 5.3.2.1 Access concentration

- 5.3.2.2 First jhana: Ecstasy or rapture

- 5.3.2.3 Second jhana: Joy

- 5.3.2.4 Third jhana: Contentment

- 5.3.2.5 Fourth jhana: Equanimity

- 5.3.2.6 Fifth jhana: The sphere of infinite space

- 5.3.2.7 Sixth jhana: The sphere of infinite consciousness

- 5.3.2.8 Seventh jhana: The base of no-thingness

- 5.3.2.9 Eighth jhana: The base of neither perception nor nonperception

- 5.4 What Is Lost in Translation

- 5.5 Renovating Buddhism: The Filter of Euro-American Ethnocentrism

- 5.6 Samatha Vipassana as a Psychological Tool

- 5.7 The Discipline of Psychology: East and West

- 6 Chapter IVConclusion

- 7 References

- 8 Source

Abstract

This paper explores evidence that Euro-Western designs of psychology are founded on a model that is culturally biased, failing in historical references and textbooks to acknowledge and give credit to earlier teachings of psychology from Eastern religions. The history of Euro-Western cultural bias in the development of the field of psychology has led to the exploitive importation of Buddhist practices without recognition or adequate understanding of Buddhist psychological theory. The author spent 6 years as a monastic and over 23 years teaching and practicing samatha and vipassana forms of meditation. Using ethnographic and hermeneutic research methodologies, this thesis demonstrates that Buddhist theory constitutes the historical origins of psychology, containing teachings that predate, yet parallel, modern Western psychology. This research also contributes to a discussion of the value of decolonizing Western approaches to psychology and understanding Buddha’s psychological theory as it pertains to meditation and mindfulness practices.

Dedication

To my wife Keiko, who has supported me from the very beginning in all my explorations of the nature of consciousness. An inspiring woman who made great sacrifices in order for me to write this. An extraordinary woman who raised our son while I wrote this. I love her with all my heart and she is the reason this was made possible. And to Siavash, without him I would never had even considered becoming a psychotherapist. He showed me the real meaning of empathic attunement with others.

Chapter I

Introduction

Area of Interest

Western academic psychology is a discipline that has historically ignored profound investigations into consciousness accomplished by other cultures. The vast majority of Western textbooks on the history of psychology make no acknowledgment of other cultural views of psychology outside of the Europeans and the Greeks (Benjamin, 2009; Goodwin, 2005; Notterman, 1997; Reed, 1997). Current histories of psychology that are widely available imply that, until the research and writings of German psychologists Gustov Fechner and Wilhelm Wudnt in the late 1800s, psychology was not considered a science and therefore did not exist as psychology (Leahey, 1987, p. 88). As a practicing Buddhist, trained in non-Western monasteries, I was dismayed to discover that students of psychology have been expected to accept that psychology did not exist until Fechner showed how the mind–body relationship could be quantified in 1850 (Wilber, 2000, p. 8).

This paper explores the evidence that Euro-Western designs of psychology are based upon a model that is culturally biased. It is not biased simply because its origins are from the West, it is biased because it fails to give credit to the earliest teachings of psychology found in Eastern religions, even though Euro-American psychology is currently exploiting those teachings. Is the whole world really meant to accept Euro-American cultural history of psychology as being objective or true even though it excludes vast psychological systems within Buddhism and Hinduism?

This thesis also explores the Euro-American view that all learning and psychological development takes place within the brain and involves thinking, a cultural and ethnocentric psychological viewpoint that is being gradually imposed upon the world (Watters, 2010; Kim, Yang, & Hwang, 2006). Euro-Western science does not currently accept or acknowledge the existence of nonlocal consciousness. Further, research in the field of psychiatry and neurobiology has posited that consciousness, apart from the mechanisms of the brain, does not exist (Schwartz & Begley, 2002). Science therefore has the tendency through its reductionist approach to want to reduce all understanding to chemical processes occurring in the brain (pp. 21-52).

A society, such as America, that claims to be built upon multiculturalism and seeks to develop a more objective science, might need to recognize that there are other forms of learning that do not involve constant memorization and intellectual comparison. According to Buddhist psychological views, much of what we call knowing in this culture, ironically, keeps a person separated from consciousness. For the purposes of this thesis, I use the word consciousness to denote pure, naked awareness that exists apart from thought processes. Thought processes are herein defined as composed of conscious or unconscious symbols in the form of images or words. A new body of research called “unconscious thought theory” (Dijksterhuis & Nordgren, 2006, p. 95) supports this definition. In the Institute of Noetic Sciences (IONS) (2013) online database, over 80 years of hard research can be found that demonstrates the fundamental differences between Western views of knowledge and consciousness and Buddhist psychological models of learning; however, these differences seem to be largely ignored by psychological sciences in the West.

As someone who has lived and studied in traditional monastic settings in both America and abroad for nearly 20 years of my life, I have found psychological work in American culture to be much more superficial than the psychological work that one undergoes in monastic settings that require mindfulness and meditation training daily. Although my theoretical and practice orientation is primarily Buddhist, I also have had more positive than negative experiences in psychotherapy over the years and have appreciated the opportunity to learn Western psychological theory and practice. This has led me to wonder why my Western colleagues would show such ignorance and disrespect when it comes to appropriating strategies from Buddhist teachings in particular. It is, however, in keeping with the pervasive trend in the history of European and American colonization of disrespecting and dominating other peoples’ worldviews and systems of knowledge—to the point that over 220 million Native Americans have been killed, entire cultures and languages lost, and assimilation tactics seem normal to us (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). This horror can be seen equally at the British Museum or the Louvre in artifacts collected through a long history of dominating, exploiting, and assimilating other cultures.

My monastic training outside of North America, and particularly in India and Latin America, brought to my attention how mistrustful many of my teachers of Eastern psychology were of Western psychology. In fact, the majority of my teachers, including indigenous shamans in the amazon and my Zen master and lama, were against me pursuing a career in Western psychology.

There is an increasing trend toward integrating Buddhist practices in psychotherapy, with more and more Americans and Europeans attending meditation and mindfulness retreats, studying with Tibetan Lamas, frequenting programs at the growing number of ashrams in the West, or practicing yoga. However, it seems that far fewer foreign Zen masters, lamas, and yogis are seeking degrees in Western psychology. It has not been an equal exchange of interest and ideas. Trying to make sense of these differences, and of why Europeans and Americans would start charging large sums of money for teachings they received for free as part of the Buddhist practice of dharma, has interested me greatly enough to pursue this research.

In this thesis I am contending that it is an entirely Euro-American perspective that before Fechner, Wudnt, and Sigmund Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, psychology did not exist, but was philosophy. My contention in this critical research paper is that Euro-American psychology is highly ethnocentric. To study its history is to see that it has almost completely failed in its presumed scientific objectivity and is, instead, ethnocentric, subjective, and has been until the last 10 years, almost entirely racist (Guthrie, 1998). Even now, into the millennium, the vast majority of Euro-American academia fails to honestly acknowledge that historically, psychology by its original definition, and even as a pure science, existed before Euro-Americans defined it as such.

Guiding Purpose and Rationale

Why is the recognition of and comparative inquiry into a psychology that predates Western models so important? We are living in a time when the world is rapidly shrinking due to the information highway, cyber colonization, and the effects of globalization. Since the millennium, mindfulness and meditation are rapidly becoming the treatment in vogue. With the advent of more and more new therapies that include the practices of mindfulness in some form, it becomes important to acknowledge that Western psychology is now going full circle historically. We are returning back to the origins of psychological practices and teachings and taking from them. However, psychologists and researchers, adapting and exploiting psychological teachings that are over 2500 years old to create new therapies, are failing to acknowledge them historically as anything containing psychology.

That European and American psychological practice has been gravely ethnocentric in defining a healthy and unhealthy sense of self cannot be separated out from its presumptive claim to the origins of psychological science. Published theories of self, going all the way back to Freud and Carl Jung, the psychiatrist credited with founding analytical psychology, focus too narrowly on what is essentially Euro-American cultural experience. Americans comprise less than 5% of the world’s population (Arnett, 2008; Population Reference Bureau [PRB], 2012). The result is an understanding of psychology that is incomplete and that can neither adequately represent nor serve humanity.

The purpose of this thesis is to establish clearly a more objective historical understanding of psychological theory and practice as a human, cross-cultural endeavor; to deepen understanding of the psychological theory behind Buddhist interventions being adopted within Western psychological practice; and to support the development of a more culturally inclusive and astute body of psychological theory and practice. As a field dedicated, at least in part, to the understanding of consciousness and human nature, psychological theory and practice should, at a minimum, accurately attribute credit for its own development. As more and more clinicians look into the teachings of Buddhism, my hope is that they might consider that to use techniques without understanding or crediting the psychological insight and theoretical lens from which they arose is a form of cultural exploitation and colonization (Teo & Febbraro, 2003). Furthermore, it deprives the field of psychology of the opportunity to deepen and broaden its conceptualization of human nature, and limits the understanding and efficacy of the imported practices. This seems, in a discipline in which much is said about the development of the authentic self, a bold hypocrisy and violation of its own integrity.

Methodology

Research problem

In this paper I contend that psychology existed systematically long before Westerners cornered the market on it with their own special cultural terminologies. I use Buddhism as the main example, as many of its psychological teachings and methodologies are currently being extracted by and misrepresented within Euro-American psychology. Although research has demonstrated benefits to the use of meditation and mindfulness (Hanson, 2009; Institute of Noetic Science, 1997; Siegel, 2007), there are nonetheless strong waves of ethnocentrism at work in how Buddhism is being represented to validate Western uses of these technologies. I attempt to give the evidence that shows that Eastern psychology existed earlier than Greek philosophy and was more sophisticated. I also wish to present evidence that the view that Western psychological theory is superior and more objective is both ethnocentric and erroneous. How can American psychotherapists who believe that thoughts and consciousness are synonymous come to understand a psychological teaching in which the basis of learning is making the mind increasingly silent so as to separate thoughts, feelings, and body from awareness?

Research question

This thesis examines the following research question: Does the reductionist understanding of Buddhist teachings common in Western psychological practice devalue, underestimate, and leave out important information that could further serve human consciousness and the field of psychology? The process of researching the importation of ancient Buddhist practices into Western psychological practice raised additional questions: What psychological theory underpinning these practices has been, and continues to be, disregarded in the Western portrayal of psychology and its history? How can Eastern psychological perspectives help broaden the scope of Western psychology? What were Buddha’s actual methods for psychological investigation as opposed to Zen methods of meditation, Hindu methods, and Tantric methods? Why do Western psychotherapists often speak and write as if all meditation and mindfulness teachings are equal when within indigenous Buddhist theory and practice there are significant variations and differences? Comparatively, in the West, many systems of therapy involve active listening skills and reflective statements, yet have their implications and applications for the treatment of psychological problems differ from one another.

Methodological approach

This thesis is both ethnographic and hermeneutic in its methodological approach. It is traditionally hermeneutic in nature to the extent that it draws upon a comparison of Western and Buddhist philosophical and psychological writings. The hermeneutic research provides a foundation and support for the ethnographic study. Ethnography is the branch of anthropology and sociology that deals with the description of specific human cultures through qualitative social science research from an “insider’s point of view” (Hoey, 2102, para. 3). As I have spent over 6 years of my life living in monastic settings that utilized traditional forms of meditation for over 6 to 8 hours a day or more, I can safely say that these are cultures that practice these skills for a living. I have lived in Buddhist, Hindu, and Christian monasteries and have experienced first person what it means to practice mindfulness and meditation not just in a secularized form, but in cultural and psycho-spiritual contexts with a group of people whose cultural origins are Buddhist in nature and who are dedicated to experiencing states of deep mental silence.

- Ethnography may be defined as both a qualitative research process or method (one conducts an ethnography) and product (the outcome of this process is an ethnography) whose aim is cultural interpretation. The ethnographer goes beyond reporting events and details of experience. Specifically, he or she attempts to explain how these represent what we might call “webs of meaning.” (para. 2)

An ethnography attempts to follow an outline that includes a brief history of the culture in question and an analysis of the environment—in this case the psychological teachings of Buddhism and the monastery. I include some description of the social structure in which one usually learns such methodologies of consciousness, some detail in the special language spoken about meditation and meditative states of consciousness, and also some of the standard topics a Buddhist monk studies regarding perception through meditative technologies.

Ethical Concerns

My primary bias is that I am an American. I have grown up an American and as such, even though I have lived and studied meditation and mindfulness in other countries where culture and economics are different, I have the strong bias of growing up in a culture where we believe in individualism and self-esteem. I have grown up under these biases believing that individuals always have the right and the opportunity to make choices in their lives. I have not grown up in a culture where choice was the privilege of very few—where the values of fate, karma, or class systems hold dominance. This describes roughly two-thirds of the world. Until I had the opportunity to live abroad, I had no idea how other cultures view Americans. I had always identified with Western culture, having grown up with the adage, “America is the greatest country on earth,” not really considering that saying this means that other cultures are subpar or beneath our way of life and understanding.

It is not my intention in this thesis to idealize or romanticize Eastern teachings, East Indian or any other culture, as each has its psychological and cultural problems. Having spent time in India in order to study the six yogas of Naropa, I have experienced this firsthand. Neither do I claim to portray the perspective of someone raised in an Eastern culture. My concern is to contribute to research that seeks to respect and understand psychological discoveries, knowledge, and practices from other cultures.

Overview of Thesis

The literature review in Chapter II reviews literature that addressed the ethnocentricity of the history of Euro-American psychology, as well as Western psychological thought itself (Alvargonzález, 2013; Arnett, 2002, 2008; Brock, 2006; Cushman, 1995; Danziger, 1997; Kim et al., 2006; Teo & Febbraro, 2003; Watters, 2010). It provides a profile of the Buddha’s teaching, comparing his psychological constructs with those of modern Western theories, to show that the majority of the psychological teachings thought to be founded by Euro-Americans had already been presented by the Shakyamuni, or first, Buddha in the Pali canon over 2500 years ago, though credit is not given to the Buddha in any of the epic historical tomes of psychology available at the time of this thesis (Benjamin, 2009; Goodwin, 2005; Notterman, 1997; Reed, 1997).

Building on the foundational understanding provided in Chapter II, Chapter III relates, from my experience as a monastic, practitioner, and teacher, the Shakyamuni Buddha’s meditation process and discusses what is commonly lost in translation as Buddhist practices are assimilated into psychotherapeutic theory and practice. Chapter III offers an analysis of some of the new wave of books that are attempting to integrate Buddhist teachings with Euro-American psychology, showing that these writings are predominantly ethnocentric and largely inaccurate, and in stripping away cultural context, leave only the bias that Western values represent objective truths. As well, examples and suggestions are offered regarding how the Buddha’s original system of samatha vipassana could deepen and broaden the scope of American psychology. Chapter IV provides a brief summary of this thesis, discusses the implications of Buddhism for Western psychology, and makes recommendations for further study.

Globalization is affecting more than just the economies of the world; it is a new term that reflects not only the way in which money moves but also the way in which humans share resources, knowledge being one of them. In the quest for objectivity in psychology, scholars and clinicians alike should consider educating themselves as to how we look at the evolution of knowledge historically. It is unfortunate that in Western academia we have begun only recently to acknowledge the wisdom of Buddhist teachings as being on an equal footing with Euro-American psychology. If we are truly living in a multicultural paradigm, and are interested in sharing an objective view of knowledge, then we in the West must be also open to giving credit to cultures that have different methods of exploring knowledge, allowing ourselves, our theories, and our practices to be stretched and deepened beyond the scope of Euro-American views.

Chapter II

Literature Review

Introduction

Americans have often excluded the knowledge of other cultures because they do not practice science in the same form as that of the West. Because Westerners developed conceptions of empirical science, unfortunately Western science cannot be separated from cultural bias. This was demonstrated very elegantly in the writings of historical scholar Finn Fuglestad (2005) when he explained,

- Although history constitutes a western discourse, it professes nevertheless to be able to investigate the past of all societies and civilizations, and the whole of the past. It follows that we are entitled to expect from history a conceptual framework that is neutral from a culture-civilization point of view. But this is the problem, granted that the production of history involves . . . cultural practices. (p. 24)

In the last few years it appears in scholarly writings that many authors are willing to acknowledge Buddhist teachings as being worthy of examination. This chapter examines evidence that Buddhist teachings are actually the progenitors of psychology and that psychology existed amongst many cultures long before it became a part of Western scientific thought.

In modern Euro-American hard science, traditional Buddhist consciousness studies have been considered philosophical rather than psychological and scientific. Modern biological sciences in fact do not acknowledge that consciousness even exists (Schwartz & Begley, 2002). One of the world’s leading experts in neuroplasticity and pioneers in the field studying obsessive compulsive disorder, Jeffrey Schwartz and science columnist Sharon Begley, in their book The Mind and the Brain, explored the subject of consciousness in great detail, helping the student of psychology understand that consciousness does not have an agreed upon definition in the West nor is it recognized in the realm of biological science.

In the 21st century, more and more people are becoming concerned with the age-old question about what constitutes the self, the brain, and the mind. Schwartz and Begley (2002) cautioned that “more and more neuroscientists are admitting to doubts about the simplistic materialistic model” (p. 49). German neuroscientist Wolf Singer noted: “These elements of consciousness transcend the reach of reductionistic neurobiological explanation” (as cited in Schwartz & Begley, 2002, p. 49). In contrast, many indigenous cultures do see consciousness as something that exists and have formed their own technologies of science to verify and explore what consciousness (Kim et al., 2006). Buddhist models that greatly influenced Asian culture are an example explored later in this paper.

One of the first openly scientific acknowledgments of the potential of Buddhist psychological methods in investigating consciousness occurred in September of 2003 at the historical conference, “Investigating the Mind,” held at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (M.I.T.) (Harrington & Zajonc, 2003). The conference was the first attempt at a dialogue and reconciliation between Western cognitive scientists and Buddhist psychological teachings. It was composed of Western scientists, The Dalai Lama, and other Buddhist psychologists. At the opening of the conference, the chairman of the Mind and Life Institute, Adam Engle, said,

- Science is the dominant paradigm in modern society for understanding the nature of reality and providing a knowledge base for improving people's lives.

Buddhism is a 2,500 year tradition focused on personal liberation, but liberation that is concerned to understand the nature of reality and use that understanding to overcome delusion. So it is the search for a better understanding of the nature of reality that forms the basis for our proposed dialogue between science and Buddhism. Buddhism uses the human mind, refined through meditative practice, as its primary instrument of investigation into the nature of reality. While this method of investigation is based on observation, very rigorous logic, and experimentation, scientists have traditionally viewed it as subjective and at odds with the objectivity of the scientific method. We believe science is wrong to reject such a mode of investigating the mind, and that there is much potential for fruitful exchange and even active collaborative research between scientists and Buddhists. This meeting has been organized to explore the wisdom and efficacy of this proposal. (As cited in Harrington & Zajonc, 2003, p. 4)

However, taking a step back from implementation of methodologies and engaging a comparative exploration of the psychological theory developed through the Buddhist approach to the study of mind and that of Western scientists raises the question of whether or not Buddhist methods and the theory behind them are being misrepresented. As discussed in the section below on the origins of psychology, as a science it began within Buddhism long before it was secularized and developed in the West (Johnson, 2002; Waldron, 2003; Wallace, 2006). American psychologists have recently begun drawing upon and creating psychological systems based upon 2500-year-old Buddhist methodologies. Currently there are at least four evidence-based psychological models that utilize Buddhist models of meditation and mindfulness: dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) (Linehan, 1993), mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) (Kabat-Zinn, 2003), mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) (Segal, Williams, & Teasdale, 2002), and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2003). Derived from distinctly non-Western theoretical ground with a completely different model of self, have Buddhist approaches been contorted by the process of grafting them onto Western theories?

Professor Thomas Teo of York University, Canadian scholar of the history and theory of psychology, and psychologist Angela Febrarro (2003), eloquently observed that

- hidden ethnocentrism is not overcome by simply assimilating ideas from other cultures, which would be a colonizing approach. In other words, a solution to hidden ethnocentrism requires a process of accommodation as well as assimilation. Euro-American human scientists must be willing to completely revise conceptualizations, if necessary, and not simply add to them. (p. 684)

How might recognizing the authentic differences broaden the Western understanding of consciousness and human nature? How might accommodation of other cultural views of psychological health inform those of us who work in the mental health field?

Such recognition and valuing of differences begins with a review of the literature related to the ethnocentric biases in the history of psychology and evidence of its pre-Western origins. A review of the literature that reveals basic Buddhist premises and of literature written by Western psychologists seeking to incorporate Buddhist practice provides a foundation for their comparative analysis.

The Ethnocentric History of Psychology

When examining the history of psychology it is interesting to note that “history is the product of the very past it purports to study. Hence history may be said to be the only academic discipline that is the product of its own object of study” (Fuglestad, 2005, p. 23). Thus it is the conquering or winning class that writes history.

In the Euro-American view, knowledge and psychology began with the ancient philosophies developed by the Greeks. In his paper on “Western Identity, Barbarians and the Inheritance of Greek Universalism,” European historian Helmut Heit (2005), professor of philosophy at the Berlin Institute of Technology, wrote extensively on the subject that he defined as Eurocentrism. Euro means “center” and Heit suggested that “ancient Greek thought has been used through the centuries to establish a superior Western identity of universal prevalence” (p. 1). This speaks to the kind of dominant and oppressive ethnocentrism through which Euro-American notions of epistemology have evolved. Mexican philosopher Enrique Dussel emphasized “that modern Eurocentrism confuses the global importance of western tradition and some of its historical achievements with a universal justification of these cultural features” (as cited in Heit, 2005, p. 728). The cultural features he spoke of included the free market, democracy, individualism, the right to determine one’s own destiny, and Euro-American scientific traditions that involve studying others from a position of objectivity.

In modern academic histories of psychology, such as From Soul to Mind (Reed, 1997), A History of Psychology (Benjamin, 2009), The Evolution of Psychology (Notterman, 1997), and A History of Modern Psychology (Goodwin, 2005), the authors have explained science, psychology, and philosophy as originating with Plato and Aristotle, eventually justifying the Whig approach to history that views later developments as superior to earlier ones. The Whig approach to history is one that seeks to emphasize the development of history relative to democratic liberties, Judeo-Christian values, and scientific progress, even at the expense of other peoples such as Native Americans (Alvargonzález, 2013). The Whig approach seeks to emphasize that the world could not have progressed and advanced without what has already passed—that no other alternative realities were possible, repressed, or need expression.

Historians of psychology, Edward Reed (1997), Ludy Benjamin (2009), Joseph Notterman (1997), and James Goodwin (2005), each portray advances as developing through Western philosophers until finally Fechner, Wundt, and Freud developed real psychology. In that psychology means “the study of the soul” (“Psychology,” 2013, def. 1), one can infer that at the turn of the century the progenitors of psychology as a field of study in the West saw their culturally biased observations of human nature and soul as synonymous. This Euro-American historical narrative, with its exclusion of the histories of racism and eugenics within 20th century psychology, has been rewritten again and again, emphasizing that all valuable origins of science come from the Greeks and reinforcing the Euro-American “identity of universal prevalence” (Heit, 2005, p. 1).

Professor of history at the University College Dublin, Ireland, Adrian Brock (2006) has spent the majority of his life studying other cultures and has tried to shine a bright light on the need to make psychology less American and less pharmaceutical. In his book Internationalizing the History of Psychology, he attempted to bring more clarity to cultural differences by having scholars from different countries share previously unknown views of psychology. Each scholar in this book, 13 in all including the author, examined the exclusion of the psychological models and discoveries of other cultures and the historical influence American and British colonization has had on this effect. Brock referred to three rules of “inclusion/exclusion in the history of psychology” (p. 3):

- The 1st rule is, If your work did not have a major impact on American psychology however influential it might have been elsewhere, it does not count. The 2nd rule is: If your work did have a major impact on American psychology, even though its influence was limited or nonexistent elsewhere, it is an important part of the history of psychology. The 3rd rule is: Asia, Africa, Latin America and Oceania do not exist. (pp. 3-5)

International journalist Ethan Watters (2010) wrote about the exportation of Euro-American ideas regarding what is mental health in his book, Crazy Like Us: The Globalization of the American Psyche. He discussed at length the bias spoken of by Brock (2006), a bias that led the pharmaceutical company Pfizer to sponsor a group of therapists to head down to Sri Lanka after the Tsunami in 2005. Pfizer was convinced that Sri Lankans were too naïve to understand the implications of posttraumatic stress disorder and that it could be very important and compassionate to make Zoloft available to treat symptoms. Ironically, for the last 2000 years Sri Lanka has been steeped in the Buddhist practices discussed in this thesis—practices that have only recently begun to be incorporated into Western psychological theory and methodology.

Pfizer’s strategy in Sri Lanka exemplified the way in which, especially with nontechnological cultures, Western Europeans and Americans have historically announced themselves as the originators of organized academics and other areas of science (Watters, 2010). From this perspective, Western scholarship sets itself up to be the standards for excellence in research and models of objectivity that study and reflect the psychology of humanity, not just a culture. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) recently opened its collective databases to cross-cultural studies with Divisions 26 (History of psychology) and 52 (International Psychology). However, professor of psychology Jeffery Arnett (2002), historian and psychologist Philip Cushman (1995), Brock (2006), and Watters (2010) called attention in their works to the ethnocentric and capitalistic values that seem to trump APA purported values of cultural competence and scientific objectivity as large pharmaceutical companies continue to export Euro-American views of mental illness abroad to boost sales of their products.

Arnett (2008), in his article, “The Neglected 95%: Why American Psychology Needs to be Less American,” demonstrated through examining 20 years of research presented in psychology journals that 95% of the psychological studies are done by Americans on Americans. Yet, “theories and principles are developed that are mistakenly assumed to apply to human beings in general; they are assumed to be universal” (p. 602). He also pointed out that as so little research has been done to understand the rest of the world, academic books used for university classes should not be titled Developmental Psychology or Abnormal Psychology, but rather should be entitled Euro-American Developmental Psychology or Abnormal American Psychology. These would be more accurate, less ethnocentric, titles that reflect the knowledge and research base. Brock (2006) commented that American textbooks are bought and circulated in universities abroad and that this has fueled part of the growing movement against American constructs of psychology and mental health, as other cultures are shocked to notice how they are excluded.

Psychology Originated in India, not in Greece

At the time Socrates (469-399 B.C.E.) was experimenting with logical argument as a way to prove what is true, in India the Upanishads had already been composed (600 to 300 B.C.E.) (Flood, 1996). The Upanishads gave an explanation about consciousness that is not clearly understandable to a culturally biased Western mind steeped in the belief that all knowing comes about through thought processes. Western academia looks upon the writings of Indian psychology as more akin to metaphysics than psychology because of the cultural need to separate psychology from any religious or indigenous views.

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, one of the older Upanishads contained within the Shatapatha Brahmana, includes teachings about the nature of consciousness and views on the nature of self. Upanishads like the Katha Upanishad teach what differentiates normal waking consciousness from the consciousness that takes place when one uses meditation methods to silence the mind (Flood,1996). The simple idea of meditation being a method to silence the mind and that stopping all internal thoughts and images is even possible is still a relatively new concept for Western psychologists to wrestle with. Even when there is now over 50 years of research into meditation (IONS, 1997), Western psychologists and anthropologists cannot allow for a cultural worldview that includes understanding aspects of reality without thought processes.

India is rife with teachings on the nature of consciousness and psychological technologies (Van Loon, 2003; Varier, 2005; Waldron, 2003). In fact, ancient Eastern alchemical texts played a decisive role in Jung’s formulation of the dynamics of the unconscious (Jaffẻ, 1968/1971). Jung (1929/1967) reported:

- Observations made in my practical work have opened out to me a quite new and unexpected approach to Eastern wisdom. In saying this I should like to emphasize that I did not have any knowledge, however inadequate, of Chinese philosophy as a starting point. On the contrary, when I began my career as a psychiatrist and psychotherapist, I was completely ignorant of Chinese philosophy, and only later did my professional experience show me that in my technique I had been unconsciously following that secret way which for centuries had been the preoccupation of the best minds of the East. This could be taken for a subjective fancy—which was one reason for my previous reluctance to publish anything on the subject—but Richard Wilhelm . . . gave me the courage to write about a Chinese text that belongs entirely to the mysterious shadowland of the Eastern mind. (p. 83)

Jung (1939/2000) also wrote a commentary that was included in the first English translation of the Tibetan Book of the Dead. In it he acknowledged how naïve the West has been to assume that because Jewish and Christian religious teachings do not contain sophisticated psychological teachings, neither do Eastern religions. In contrast to the either-or thinking regarding good and evil, and heaven and hell, of Western religious teachings, and the dualistic separation of religion and science in the West, in his commentary Jung appeared to stand in awe of how Buddhists came to the conclusion that both heaven, hell, and all possible after-death states are psychological, and that perception after death is based upon states of consciousness that were cultivated in life. How could people, presumed in the West to be primitive, have come up with this understanding? The following are various examples of psychological understanding that existed long before the development of the field of psychology in the West.

Ayurvedic medicine

Ayurvedic medicine is the comprehensive medical system indigenous to India that originated over 5,000 years ago (Prasad, 2013). Although Ayurveda is considered a form of complementary alternative medicine in the U.S., nearly 80% of the population of India uses it exclusively or in combination with conventional medicine. It is one of the oldest medical systems in the world, with eight branches of study, one of which is psychiatry and psychology. Defined as the science or knowledge of life, Ayurveda considers prevention of disease and promotion of mental health to be principal and the treatment of psychological and physical disorders to be secondary.

Ayurveda’s classical texts, such as the Charaka Samhita and the Sushruta Samhita, state that the mind (sattva), consciousness (atma), and body (sharir) comprise the foundations of life (Van Loon, 2003). Thousands of years before the arrival of modern psychology, Ayurvedic physicians had analyzed the nature, functions, phenomena, and conduct of the mind and consciousness in intricate detail. They described two broad aspects of consciousness: (1) the mind (manah or manas), defined as that which imparts, renders, and facilitates knowledge by use of the senses and reasoning, and (2) pure consciousness (buddhi), that, existing outside of judgments and evaluations, is unhindered by mental and emotional complexes and has the capacity to discriminate what is true without bias (Varier, 2005). Buddhi is a state of consciousness that can only be understood when the mind has become still and silent.

Classical Ayurveda details three principal attributes of mind, called the trigunas, and 16 major types of mental natures (manas prakruti), and discusses prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors that influence the development of these types (Varier, 2005). In addition, Ayurveda expounds upon various operations of the mind, including sensory perception, motor action, memory, contemplation, deliberation, reasoning, judgment, sense of self, sleep states, and dreaming. Ayurvedic teaching also expounds upon behavioral patterns that are learned, and the impact of various emotional states on the mind and body.

The teachings of the first Buddha

The Shravakayana view of Buddhist psychology follows the philosophy of empiricism that holds “that knowledge should be acquired through observation and experimentation” (Benjamin, 2009, p. 21). Socrates is said by scholars to have lived from 470 to 399 B.C.E. (Flood, 1996); yet given this time frame, if one examines the teachings within the Buddhist sutras, one can easily surmise that the psychological teachings of Socrates were not as well developed as those given by the Buddha in 500 B.C.E. nor that of the Upanishads in India. The teachings that are ascribed to the Shakyamuni Buddha include schematics on the nature of perception (Bodhi, 2000; Wallace, 2006), teachings on psychoanalysis (Bodhi, 2000; Dhammadharo, 1959/2010; Johnson, 2002; Waldron, 2003), and a profound discourse on cause and effect equal to Newton’s later theories (Buddha called this dependent origination) (Bodhi, 2000). These same ideas would take over 1500 years to develop in Euro-Western thought. This has only recently come to light and been acknowledged by western researchers, who have historically viewed Indo-Asian scholarship with distrust (Harrington & Zajonc, 2006).

Consider the following list of phenomena the Buddha discussed in the Samyutta Nikaya (Bodhi, 2000): greed, hatred, delusion, ignorance, grasping, craving, sense perception, becoming, ageing, concentration, nonattachment, dispassion, equanimity, tranquility, trust, gladness, and liberation by insight. These phenomena, which the Buddha taught about from his own gnosis and the gnosis of his monks, are dhammas, conditioned physical and mental processes. Abhidhamma-pitaka refers to the concept of mind-consciousness (“manovinnana” in Pali), the primary cognitive operation within the process of perceptual discrimination. These are clearly complex psychological teachings going back at the very least 2000 years, as found in the Vishudhimagga, the Buddhist manual and schematic of inner states (Buddhaghosa, 1991). However, Westerners have regarded Asian forms of psychological investigation with a type of cultural skepticism that might be the result of a failure to understand their technology of the mind (Danziger, 1997, pp. 1-9).

Buddhist scholar William Waldron (2003) published a book revealing that 1500 years before Freud’s discovery of the unconscious, in the Mahayana sutta of the Alaya Vinaya, the Buddha discussed the unconscious at length. Waldron pointed out that in the 5th century Indian Yogacara Buddhists, on the basis of their experience of samadhi in meditation, described in great detail the nature of consciousness and the vast differences between forms of unconsciousness and consciousness. In fact the word buddha, the title given to the man Siddhartha, suggests an awareness of the unconscious mind historians have accredited to Freud and Jung. Buddha (from buddho) means “awakened” (“Buddho,” 2013, def. 1), referring to consciousness as opposed to unconsciously conditioned, unaware, or hypnotized by physical sensations (Thanissaro, 1997).

Siddhartha’s initiatory title in itself implies a deep understanding of the difference between someone who has a manifested understanding of awareness (consciousness) and one who does not. One of the Buddha’s central teachings was a form of what would be labeled in the West as behavioral psychology. In the Samyutta Nikaya (Bodhi, 2000, 56:11) and the Majjhima Nikaya (Nanamoli & Bodhi, trans. 1995), Buddha explained in detail in his teaching on the four noble truths how behavior is conditioned by external and internal causes and effects.

Kurt Danziger (1997) is an internationally known research psychologist who pioneered examinations of the history of psychology from a cross-cultural point of view in contrast to the Whig perspective perpetuated in many American universities. In Naming the Mind: How Psychology Found its Language, Danziger asserted that western culture has historically measured other cultures’ understanding of psychology by looking for references to self-objectification (pp. 21-25). Euro-American historians of psychology have created a timeline for self-objectification, or what might also be termed self-observation. This timeline has excluded Asian cultures because it was believed that they had neither an understanding of consciousness nor a sophisticated way of using or explaining self-objectification in their writings (pp. 21-35), even though Buddha’s teaching on mindfulness is a concise teaching on self objectification. According to Danziger, Euro-American psychologists remained aloof from examining the psychological implications of Hindu and Buddhist teachings even when the British occupied India.

Importing Psychoanalysis to India

Psychoanalysis was established in India in 1915 at the University of Calcutta when the first chairman of the Department of Experimental Psychology was trained under Hugo Munsterberg at Harvard (Paranjpe, 2006). However, Western psychoanalytical teachings made little to no progress in India; in fact most Indian researchers and psychologists simply replicated experiments done in the West and tried to convert Indians to the Western views of psychology. According to expert in the history of Indian psychology, Anand Pranjpe, in 1980, the Indian psychologist Udai Pareek concluded that psychological studies in Indian universities were almost at a standstill and at risk of becoming irrelevant in India. Pareek called for Indian psychologists to pay less attention to how Westerners looked at psychology and to look instead back into their own rich history of psychology as well as into the social realities occurring in present India (Paranjpe, 2006, p. 66). Before embarking upon a schematized explanation of how Buddha had already taught many of the psychological concepts that have been rediscovered, renamed, and reexamined in Euro-American systems, it is important to understand some of the basic foundations of the teachings of Buddhism.

Brief Background of the Schools of Teaching Within Buddhist Psychology

This next section draws upon the scriptures of Buddhism to explain the Buddha’s primary methodologies for psychological change. It also reviews his theories of self, consciousness, and cognition. It compares Buddhist thought from 2500 years ago with parallel teachings from modern western psychology. While the Buddha did not invent meditation, he did set out to find a way to eliminate reoccurring patterns of behavior in a degenerating form of Bhrahmanism.

The teachings of the Buddha began as an oral tradition, but were eventually written down as a set of scriptures (Snelling, 1998). The scriptures of Buddhism began with what are known as the sutras (sutta in Pali). There are three collections of sutras that give the teachings of the first historical Buddha Shakyamuni. These are known as the Digha Nikaya, the Majihma Nikaya, and a collection of short sutras called the Samyutta Nikaya, Anguttara Nikaya and Khudakka Nikaya. In English, they are called respectively the long discourses of the Buddha, the middle length discourses of the Buddha, and the connected or short discourses of the Buddha. The three collections of the original teachings of the Shakyamuni Buddha are known as the Tripitaka or the three baskets—a name that resulted from the fact that “the entire scriptural canon of the school was rehearsed, revised and committed to writing on palm leaves between 35-32 B.C.” then placed in three baskets ( p. 81). Today most scholars derive their historical knowledge of ancient India from the sutras, as there are few other written source materials describing that period of history.

Buddhist scholar and historian John Snelling (1998) was former general secretary of the Buddhist society, which was founded by D. T. Suzuki, Christmas Humphreys, Edward Conze and supported by the 14th Dali Lama in 1924. The Buddhist society has been dedicated to making translations of Buddhist texts and history available freely to westerners. Snelling (1998) stated that within 100 years of the Buddha’s death, his teachings divided up into 18 different schools. Over the next 10 centuries, there arose numerous divisions within the interpretation of the Buddha’s teachings. Nearly all Buddhist traditions in the world agree upon the story of the Buddha’s life up to the point where he reached enlightenment. According to the Majhima Nikaya (Bodhi, 2000), Buddha meditated for 6 years under the Bodhi tree before he reached enlightenment. After this, he began to teach the four noble truths, the eightfold path (in the Dhammacakkappavattana sutta), and the teachings of dependent origination (in the Nidanasamyutta sutta).

Most all Buddhist philosophical systems agree on these three as the foundation of their teachings. Yet, it is after this point in Buddhist thought that many divisions occur in the way enlightenment is viewed: Was it full or partial enlightenment that Buddha developed throughout his life? What does enlightenment mean? What did Buddha’s enlightenment mean? How does one attain the same enlightenment that the Buddha found? These questions are all points of contention between the different schools and sects of Buddhism. These would eventually synthesize into three major schools of philosophy: Shravakayana, the lesser vehicle (Hinayana), Mahayana, the greater vehicle, and Vajrayana, the diamond or tantric vehicle (Blofeld, 1992).

In Sanskrit, the word yana means vehicle (Snelling, 1998), and a vehicle, like a car, is a technology that you use to get from one place to another; so too are the triyanas (three yanas), the three vehicles of the dharma, a Sanskrit word that refers to righteousness and duty, the inner constitution of a thing that governs its growth, and the fruit of good actions that we receive as compensation (Schreiber, Erhard, & Deiner, 1991). It also means the law or the way: The teachings themselves are the dharma. The analysis in Chapter III comparing Buddhism and its importation into Western psychological practices builds upon the differences between the yanas of the three Buddhist schools in their approaches to psychological change and acquiring gnosis.

Shravakayana

A foundational path in the Eastern traditions, the Shravakayana school’s name derives from the word shravaka, meaning hearer, and yana, meaning vehicle. It is an introductory path, a teaching that can accommodate any person in order to provide them with the information they need to go further (Snelling, 1998). Shravakayana has been called Hinayana, a derogatory name meaning the little or lesser vehicle and implying a narrow-mindedness that excludes the larger perspective because it refers to those seekers of the dharma who only rely on the teachings of the first Buddha. It also connotes a kind of arrogance amongst Mahayana Buddhists who see the Shravakayana as ignorant for not readily accepting other future teachers of the dharma.

The foundational path is the form of religion that teaches the very basics of spirituality and how to understand the consciousness. In Buddhism, this includes the four noble truths (Snelling, 1998). The first noble truth expresses the basis of life: that life is suffering. This is the first thing any spiritual aspirant must understand deeply, not just intellectually but by direct experience. Buddha taught that understanding the nature of karma and the nature of suffering is the purpose of the foundational path. It is in this level of work that an aspirant is taught how to meditate, concentrate, pray, self-observe, be aware, and be mindful. But all of these things are committed to comprehending the nature of suffering, and the nature of karma. Following the Shravakayana approach means that one adheres to the original teachings of the Shakyamuni Buddha and the three baskets of suttas, the tripitaka. Samatha vipassana, the Buddha’s original system of meditation that builds concentration through specific objective states leading ultimately to insight and consciousness, is discussed in detail in Chapter III from the author’s experience as a monastic and meditation teacher.

Mahayana

Mahayana is called the great vehicle, because it is, in a sense, inclusive of all the different schools and views of Buddhism (Snelling, 1998). Mahayana teachings differ strongly from Shravakayana around the point of how is it that one attains enlightenment. The Mahayana view focuses more on the belief in the bodhisattva ideal and the notion of emptiness (Sunyata). They view the Shravakayana School as being a teaching of the spiral path, meaning that it could take many lifetimes to attain enlightenment, in which the practitioner is focused mainly on the development of his own enlightenment and not helping others. Although this is a critique held by many practitioners of Mahayana teachings, many practitioners of Theravada see this as a complete misunderstanding of the Shravakayana philosophy.

Following the Mahayana approach means that one is open to any kind of Buddhist teaching that comes from any school regardless of whether it contradicts the first Buddha’s teaching or many of the teachings of Mahayana do (Snelling, 1998). Chan, or Zen Buddhism, is one of the most liberal schools under the branch of Mahayana. Zen masters throughout history have been known to break the precepts they have taken as monks and still be considered monks. For example, modern American Zen teachers may drink alcohol regularly, even getting drunk, and still be considered Roshis (a recognized Zen master who is thought to have attained a certain level of enlightenment by his Zen master peers). The Taizen Maezumi Roshi, who died because of his disease of alcoholism, would be but one instance of this (Tebbe, n.d.). This would not be acceptable in the Shravakayana approach.

The vast majority of Mahayana practitioners believe that enlightenment can be obtained through good works, helping others, and teaching the dharma (Snelling, 1998).

Less emphasis is placed on meditation practice and monastic training in the path to enlightenment. The psychological practices of Buddhism are downplayed and replaced more with faith and belief in the Buddha as a savior. Schools such as the Nichiren Daishonan sect and the Pure Land school reflect this belief (p. 134) and hold that chanting certain mantras alone can bring about entrance into a heavenly realm without the need for the eightfold path and renunciation (p. 157). Though nirvana is described by the Buddha in the Samyutta Nikaya (Bodhi, 2000) as simultaneously being the extinction of the fire of desire and a celestial kingdom, this view seems to later drastically change within the Chan and Pure Land schools (Snelling, 1998). The Chan school views nirvana as a perfect psychological state of nonduality that destroys notions of a self, brought about through the persistent meditation method of Mo-Chao (serene observation of the mind practice). Pure Land views nirvana as a celestial kingdom wherein the very atmosphere causes nonduality to manifest effortlessly. The attainment of nirvana using Pure Land’s methodology only requires devotional practice and recitation of the suttas.

This view of Pure Land Buddhism is diametrically opposed to what is taught in the tripitaka, and is one of the significant differences between the Mahayana view and that of Shravakayana, and much more akin to the philosophy of Christianity. Mahayana has its own set of sutras that began appearing over the first 1000 years after the Shakyamuni Buddha’s teachings. Snelling (1998) stated,

- Often the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, is cited as author, and fictions have to be advanced to explain why the works in question took so long to come to light. It might be claimed, for instance, that the Buddha had decreed that a particular sutra be hidden away until such a time as the world was ready to receive the unusually deep teachings that it contained. (p. 87)

Followers of Mahayana claim that many of these teachings are the esoteric teachings of the Buddha given only to a select few during his lifetime. This is, however, contradictory to what Shakyamuni taught (Digha Nikaya, 16), in that he told his monks that he held back no esoteric or secret teachings; everything was given freely.

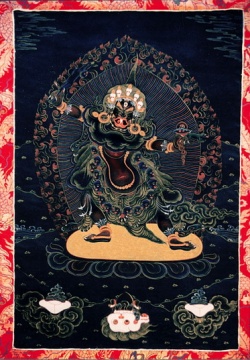

Vajrayana

The Vajrayana schools of Buddhism use tantra or ritual magic as their primary form or method to obtain enlightenment. John Blofeld (1992), scholar, tantric practitioner, and religious anthropologist, wrote extensively and with great clarity on what constitutes the various practices of Buddhist tantric teachings. In his writings he shared openly about the Vajrayana teachings. The Vajrayana system, like the others, utilizes meditation and mindfulness but it also emphasizes the use and necessity of ritual magic to investigate higher and lower states of consciousness. It must be understood that tantra is a very sophisticated psychological system that involves much preparation and years of training. Most Western writings on tantra are very biased towards sex and present a misconstruction of the tantric teachings. Blofeld discussed western misunderstandings about tantra extensively in his book The Tantric Mysticism of Tibet.

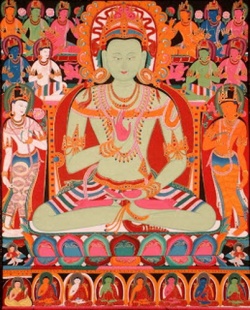

Following the Vajrayana approach (that of the Dalia Lama), means that one starts with the Shravakayana approach but one has the possibility to also graduate to levels of enlightenment that work with higher and lower planes of consciousness, the investigation of after-death states, and the use of ritual magic. One would need to study for 6 years before one would be allowed to begin practicing tantric teachings (Lama in Dharamsala, India, personal communication, November 1995). In terms of meditation, Vajrayana is unique in that samatha vipassana is emphasized in some schools of teaching, and in other tantric systems, such as the six yogas of Naropa, the well-known practice of mahamudra meditation is taught. Mahamudra involves constantly returning attention to look for the source of the attention itself; it can be used as the primary vehicle to bring about deep, nonconceptual, nondual states of silence.

Further investigations into the psychological systems taught by the Buddha will bring one eventually to a large series of writings attributed to the Shakyamuni Buddha called Abhidhamma, the last of the tripitakas constituting the Pali Canon (Access to Insight, 2012). Oral tradition among the Bhikkus (Pali for monks) has said that Buddha came up with the teachings referred to as the Abhidhamma after his first enlightenment under the Bodhi tree. He later taught it to the Devas (Sanskrit for angel or gods). Later he would teach it to Sariputta, another monk who was praised by the Buddha as being foremost among the bhikkhus in terms of his discernment. In Abhidhamma one can find extensive, meticulous, and categorical details on how cause and effect condition one another within the context of not just one lifetime but many.

Non-Western Models of Self That Have Been Discounted and Overlooked

Before reviewing Buddha’s teachings against modern psychological theories, it is crucial to acknowledge that the Euro-American approach toward other cultures’ models of self has been to marginalize and ignore them almost completely (Watters, 20120). What follows is a brief presentation of a few examples of Asian models of self that are different from ones that reflect Euro-American worldviews. This discussion is crucial to understanding the potential of Buddhist practices as they function within the context of Buddhist psychological theory. Acknowledging that Western concepts of self are neither definitive nor universal calls upon Western mental health practitioners to question assumptions and be willing to revise theory and practice. How might recognizing the authentic differences broaden our understanding of consciousness and human nature? How might accommodation of other cultural views of psychological health inform those of us who work in the mental health field?

Euro-American culture was influenced for almost 300 years by the Judeo-Christian religion until the last century, when there occurred a strong surge to polarize life, separating science and a secular society from religion. In contrast, Asiatic culture has been largely influenced by Daoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and Hinduism, all religions that are non-anthropomorphic and inclusive in their attitudes toward other belief systems (Kim et al., 2006). Is there a relationship between the intolerance of other religions for the last 1500 years in Euro-American cultures and the disregard for other cultural views of self and psychology? In 2006 a book was published called Indigenous and Cultural Psychology (Kim et al.) that featured findings from scholarly research on Eastern models of psychology, self, and perception from across Asia. The Asian scholars in this presented strong arguments against the usurpation of mental health standards by Americans and against Americans setting cultural norms and standards for the world.

The development and constitution of a sense of self

Kuo-shu Yang (2006), a professor at the Department of Psychology at FuGuang College of Humanities and Social Sciences in Taiwan, has orchestrated psychologists in Taiwan, China, and Hong Kong to create an academic movement that studies and supports the indigenization of psychological studies and research in Asian culture. In her article, “Indigenous Personality Research,” she presented a nonlinear model comparison between an American’s sense of self and that of a Chinese person. She emphasized in her writing that, although the Chinese do believe that one must have a good childhood attachment to parents, how a person develops a sense of self-worth and relationship to the outer world is based on a radically different model than found in North America. In her comparison of American and Asian models, Yang (2006) contrasted the relative degrees of importance of individual-oriented, as well as relationship-, group-, and other-oriented personality attributes in the construction of a sense of self. In American culture individual orientation creates the most significant and largest aspects of self, next comes group-oriented attributes, followed by relationship-oriented, and then other-oriented qualities. In Asian culture the range is almost reversed: Individual-oriented attributes are the least significant, and group- and relationship- orientation are the most important aspects of self, with other-oriented attributes falling in between. This is reflected in the stronger emphasis on self-determination and individualism in American than in Asian cultures.

The self, the nonself, absolute truth, and relative truth

In concert with the Asian understanding that an individual’s sense of self arises from and is supported by attributes that connect the person with others, the Buddha understood that human beings are born into a relative truth in which we adapt to the conditions of those social and cultural environments that are regarded as true at the time (Bodhi, 2000). In Buddhist psychological teachings, from the very beginning, the Shakyamuni Buddha put forth his own gnosis that there are two types of truth and levels of gradation between them, absolute truth and relative truth. This is found in the Samiddhi sutta in the Samyutta Nikaya and is an important and often overlooked fundamental teaching, as important as the four noble truths. He taught that in order to escape the suffering and subjectivity of relative truth, in order to experience absolute truth, one must eliminate the notion of self. For it is the notion of self that makes reality into a subjective experience based upon attachment to sensations, feelings, and mental discriminations, preferences and opinions regarding those experiences.

Rather than using intellectualism and mathematics to study the nature of reality, as described in the Anguttara Nikaya (Thera, 2000, suttas 2.30, 4.170, 10.71) and the Samyutta Nikaya, (Bodhi, trans. 2000, sutta 35.205), Buddha brought forth a sophisticated form of psychology, based upon his own gnosis. He taught a system of psychological work in which a specific order of objective states of consciousness called jhanas are developed through a discipline of concentration and a process of meditation he called samatha vipassana. Samatha is Sanskrit for tranquility, referring to the tranquility that comes through the stillness and silence of the mind. Vipassana is Sanskrit for insight. In the system Buddha taught, first one must develop concentration. After concentration is developed, one can develop insight. Through insight one’s concepts of reality eventually reveal an objective reality beyond the subjective experience of selfhood. At the level of objective reality, or absolute truth, there is no self to discriminate, which means that the experience of reality flows freely within the body. However, in the realm of relative truth, no matter how advanced the practitioner is along the path, as long as he or she has ego (defined here as thoughts and desires), he or she will continue to see truth in a way that is unconsciously effected by the egoic aggregates.

The Buddha’s teaching of anatta (Pāli) or anātman (Sanskrit), referring to “non-self” or “absence of separate self” (Nanamoli & Bodhi, 1995, Alagaddupama sutta 22), is the core of his psychological theory. The Buddha expressed this when he said,

- Monks, there are these six view-positions (Pali.-ditthitthana). Which six? There is the case where an uninstructed, run-of-the-mill person—who has no regard for noble ones, is not well-versed or disciplined in their Dhamma; who has no regard for men of integrity, is not well-versed or disciplined in their Dhamma assumes about form: “This is me, this is my self, this is what I am.”

- He assumes about feeling: “This is me, this is my self, this is what I am.”

- He assumes about perception: “This is me, this is my self, this is what I am.”

- He assumes about fabrications: “This is me, this is my self, this is what I am.”

- He assumes about what seen, heard, sensed, cognized, attained, sought after, pondered by the intellect: “This is me, this is my self, this is what I am.”

- He assumes about the view-position—“This cosmos is the self. After death this I will be constant, permanent, eternal, not subject to change. I will stay just like that for an eternity: This is me, this is my self, this is what I am.”

- Then there is the case where a well-instructed disciple of the noble ones— who has regard for noble ones, is well-versed & disciplined in their Dhamma; who has regard for men of integrity, is well-versed & disciplined in their Dhamma assumes about form: “This is not me, this is not my self, this is not what I am.”

- He assumes about feeling: “This is not me, this is not my self, this is not what I am.”

- He assumes about perception: “This is not me, this is not my self, this is not what I am.”

- He assumes about fabrications: “This is not me, this is not my self, this is not what I am.”

- He assumes about what seen, heard, sensed, cognized, attained, sought after, pondered by the intellect: “This is not me, this is not my self, this is not what I am.”

- He assumes about the view-position—“This cosmos is the self. After death this I will be constant, permanent, eternal, not subject to change. I will stay just like that for an eternity: This is not me, this is not my self, this is not what I am.”

- (Alagaddupama sutta 22)

At the time of the Shakyamuni Buddha it was a commonly held view among Brahmans that the self (or in Sanskrit, the atman) was synonymous with thoughts; that, but for the body, our identity is almost one with the spirit. This was an interpretive view that the Buddha reacted against in his own teaching. The Brahman interpretation of the atman was reflected in the following verse from the Mundaka Upanishad:

- The one on whom the veins converge, like spokes on the hub of a wheel, that one moves on the inside, becoming manifold. Meditate this on the self. The one that consists of mind, the controller of the breaths and the body, who is established in food, having settled in the heart, with the perception of him by means of their intelligence, wise men see it. (As cited in Wynne, 2007, p. 69)

Explaining the Buddhist path to self-realization—a path that involves a model of self-dissolution rather than self as thought or spirit—necessitates using metaphoric language that reflects experiences but cannot contain them. Scientist Mathieu Ricard (Wallace, 2006) discussed this same phenomenological problem regarding perception with the monks who attended the “Investigating the Mind” conference at M.I.T. It becomes very difficult to explain to a self-concept how to dissolve itself. When one begins the practice of mindfulness for example, it is often practiced intellectually. One confuses thinking about mindfulness or thinking about the environment with actual mindfulness. Instead, mindfulness is a state of objective self-observation, in which one uses one's attention to observe the source of that attention. When this happens correctly the very act of this type of self-observation separates the awareness from one's thoughts, causing thoughts to fall away. This action can be very confusing to a person who feels their center of gravity within their thoughts. There is a human tendency to evaluate every experience, so when beginning to understand mindfulness, the student tends to ask, “Am I doing it correctly?” Thus the observation stops and evaluation begins.

It is possible that the Buddha experienced witnessing these very same struggles within the Brahmans and practitioners of his time, constantly evaluating where they were on the path to atman, or if they were on the correct path at all. It can be assumed that he held such a position based upon the fact that he continually engaged the Brahmin priests in the debate between atman (pure being or unconditioned consciousness) or anatman (nonconstructed consciousness), and the lack of gnosis they had about this for themselves. In the Tevijja sutta of the Digha Nikaya (Walsh, 1995), the Buddha dealt with these issues when two young Brahmins came to him for counsel regarding an argument about which of their teachers was more astute regarding the path of union with Brahma. The Buddha discussed this with them and through questioning got them to realize that these teachers had no direct experience, no gnosis of what they were teaching. He assisted them in understanding that they had believed in a false teaching. He further insisted that he had direct experience of Brahma and could show both of them how to experience Brahma for themselves.

The Buddha emphasized that there was no subjective soul or self—meaning the self-identity that is based in one’s thoughts and internal dialogue—that is reborn or that lives after death in a heavenly eternity (Bodhi, 2000, Assutava sutta 12). The Brahmins believed in a subjective soul or self that returns over and over according to its karma. This is a kind of repetition compulsion that the consciousness is subjected to. It is this belief in a soul characterized by mind that the Buddha taught against in the Majhima Nikaya (Nanamoli & Bodhi, 1995, sutta 22); there is no continuity of conceptual consciousness characterized by an internal dialogue. This does not mean, however, that the Buddha taught nihilism or total dissolution of awareness. The Buddha, within the suttas, implied many times that there is a continuity of consciousness (pure awareness), however he was struggling to teach against the habit of constantly needing to intellectually conceptualize consciousness, as the Brahmins were doing and the West has done. His emphasis was instead on the fact that when one lives from consciousness, there is no need to continually evaluate experience, rather experience needs to be observed as it already contains gradations of truth. This is known further as one uses mindfulness to separate from the five skandhas, or aggregates (discussed below), and works on dissolving the flow of mental formations, or sankharas.

The five skandhas and sankharas

In the Samyutta Nikaya (Bodhi, 2000), the Buddha described the objective reality of aggregates that constitute a person when seen from a position of wisdom: “The noble bodhisattva, Avalokitesvara, engaged in the depths of the practice of the perfection of wisdom, looked down from above upon the five skandhas, and saw that they were empty in their essential nature” (Heart sutta 22). The first aggregate or accumulation is called form. An individual “assumes form (the body) to be the self, or the self as possessing form, or form as in the self, or the self as in form” (Heart sutta 22). Here the Buddha expressed that one who is identified with their physical body as their identity; this one holds a wrong view. He said that the self is not the body.

The Tibetan Book of the Dead (Evans-Wentz, 1927/2000), a teaching coming from later Vajrayana Buddhism, expanded on Buddhas’s original teaching in terms of the law of karma and reincarnation. Because we as humans are identified with a body, we wish to see ourselves in a body as part of our identity; this is why we keep returning into bodies. Typically, American culture does not embrace what Asian culture defines as the law of karma (meaning cause and effect) as extending beyond basic Newtonian physics.

The second aggregate is called sensation or sensibility, though often it is translated as feeling (Bodhi, 2000). This aggregate refers to the experience of sensation through the five senses. The third aggregate is usually called perception: It is here that the mind begins to translate the sensation into a feeling of like or dislike. It is here that previous conditioning of the mind interferes and the mind begins discrimination and labeling of sensation. The perception that is formed becomes associated to other previous perceptions creating now the fourth stage of the aggregate.

The fourth aggregate is impression (in Pali, sankhara and in Sanskrit, samskara) (Bodhi, trans. 2000). At this stage, the sensation has been fully transformed into a powerfully acting, often unconscious mental formation. Energy (called chi in Chinese) becomes bottled within the form and this formation/impression remains stored in the mind—comparable to what in Jungian psychology is called a complex, “an emotionally charged group of ideas or images” (Sharp, 1991, p. 37). Buddha understood that at a later point in time, a similar event will trigger the same inner state to come forth as the previous one, therefore, this skandha is the creation of karma (Nanamoli & Bodhi, 1995, sutta 41).

The fifth skandha is consciousness. The consciousness is conditioned by the impressions and the karma (Nanamoli & Bodhi, trans. 1995). The Buddha taught that human consciousness is asleep and usually only perceives the sensations after the previous skandhas transform them into desires of craving or aversion. When one comprehends and eliminates the sankharas or karmic forms, then one begins to comprehend the inherent emptiness within those forms.

Rather than arising from hermeneutic research or clinical experience, this aspect of the Buddha’s psychology was founded on a concentration that separated his awareness from thought processes and other inner reactions so that he was able to observe the nature of how perception functions at a precognitive level. Buddha’s approach to and findings regarding the perceptually based psychological nature of the self in relationship to absolute truth and pure consciousness contrast with what Schwartz and Begley (2002) pointed to as the reductionism of neurobiological explanations and illustrate a nonwestern technology for exploring and understanding consciousness and the experience of self.

Structural Examples of Psychological Theories Taught by Buddha

The psychological findings that the Shakyamuni Buddha derived from his methodology provide an understanding of the human psyche, relationships, and behavior comparable to, yet vastly predating, western schools of thought, including psychodynamic theory, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), theory of the unconscious, and object relations. The comparison that follows of Buddhist and Western psychological systems provides a foundation for the critique in Chapter III of the way in which Buddhist practices have been understood and used in the West.