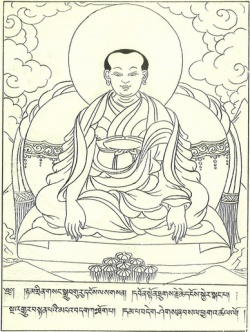

The round sutra collection I

(Skt: samanta-sutra-samuccaya; JP: en-kyo).

Compiled, edited and translated by

Jotidharma Douglas D. Morom.

2003 C.E. and ongoing.

CONTENTS

[1] Introductory Comments.

[2] Text of the Round Sutra Collection.

[3] Conclusion.

THE ROUND SUTRA COLLECTION

(samanta sutra samuccaya)

Homage to the of supreme reality lotus blossom teaching. The awakened nature of root cause supreme.

[Skt: Namah saddharma-pundarika-sutra-adi-hetu-buddhaya; Jp: Namu-myo-hoh-ren-kay-kyo-butsu-hon-nin-myo

Homage to the balanced, and full awakening of the such come, the exalted, and the noble one.

[[[Pali]]: Namo tassa tathagato, bhagavato, arahato, samma sam buddho.]

Homage to the awakened-one.

[Skt: Namah-buddhaya; Jp: Namu-butsu; Pali: Namo-buddho.]

BOOK ONE

1.1

Kalama sutta. Selected passage.

[1] Come now, kalamas, be not satisfied with mere hearsay, [2] nor customary belief, [3] nor with legendary stories, [4] nor with your revered books, [5] nor with mere speculation, [6] nor with mere reasoning, [7] nor with the seeming evidence of the senses, [8] nor with a biased opinion personally thought out, [9] nor with another’s ability, [10] nor with the thought: This wanderer is our teacher. [11] But, kalamas, when you know for yourselves that these teachings are beneficial, without mistake and praised by the wise, then you should enter in and abide by them. [12] For when they are received and put into practice they lead to well being and much blessing.

1.2

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Whether the tathagatas, the-such-come, arise in the world or whether tathagatas do not arise in the world, it remains an established condition, an unvarying fact and an unalterable dharma, an-unalterable-reality, that all that is constructed is ever-changing; that all that is constructed is without-lasting-satisfaction-and-insecure, and that all dharmas, all-conditioned-realities, are non self.

1.3

Uncompounded Sutta. Udana. Pataligamiya chapter. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, there is a ajatam, a-not-born; a abhutam, a-not-become; a akatam, a-not-created, and a asankhatam, a-not-constructed. [2] Bhikkhus, if this not born, not become, not created and not constructed was not, there would be no liberation from that which is born, become, created and constructed that could be known. [3] But bhikkhus, since there is a not born; a not become; a not created, and a not-constructed, there is a liberation from that which is born, become, created and the constructed that can be known.

1.4

Digha nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] The buddha-nana, or-the-awakened-knowing, is preeminent, boundless and everywhere illuminating. [2] Here, neither earth, water, fire, air; nor long, nor short, nor refined, nor unrefined, nor pleasant, nor unpleasant; nor nama, that-which-names, nor rupa, appearing-colour-form have any foothold. [3] Here, all that-is-dependently-arisen, is absent. [4] Through the overcoming of avijja, or-the-overcoming-of-unseeing, all that-is-dependently-arisen is thereby overcome.

1.5

Chedana sutta. The Cutting through teaching.

[1] Such i heard. At one time. [2] The exalted one said: Appearances, feelings, memories, desires and thoughts are ever-changing. [3] Whatever is ever-changing, is dukkha, without-lasting-satisfaction-and-insecure. [4] Whatever is without-lasting-satisfaction is nonself. [5] Whatever is nonself, is not-me, not-mine, and not-i. [6] This is how everything should be regarded as it truly is with insight. [7] One who develops insight in this way, understands the danger in taking appearances, feelings, memories, desires and thoughts as me and mine. [8] Understanding the danger in grasping at things as self, one no longer grasps at them-as-self. [9] No longer grasping at them-as-self, one is freed. [10] Being freed, there is the knowledge of being freed. [11] Thus one realizes that unseeing is cut off; the brahma-cariya, the-sublime-life is lived, and the task complete. [12] In the midst of dependently arisen and ever changing things, there is unshakable liberation.

1.6

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Whoever sees dependent-arising sees the dharma, sees-the-real, and whoever sees dharma sees dependent-arising.

1.7

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh vikkali, why do you stare at this corruptible body? [2] Whoever sees the dharma, or-whoever-sees-the-real sees me and whoever sees me, sees the dharma. [2] Oh vikkali, in seeing the dharma one sees me, and in seeing me one sees the dharma, one-sees-the-real.

1.8

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Is it true that the tathagata, or-the-such-come is compassionate towards all living and breathing beings? [2] Yes, oh headman, replied the exalted one. [3] But does the exalted one teach the dharma, teach-the-real in full to some but not in full to others? [4] Oh headman, suppose that a farmer is possessed three fields, an excellent one, a middling one, and a poor one with poor soil. [5] Now when he wished to sow seed, which field do you suppose that he would sow first? [6] He would sow the excellent one first, then the middling one and when he had done that, he may sow the poor field with the poorest soil for the reason that it might be good for cattle feed. [7] Oh headman, in the same way, my bhikkhus and bhikkhunis are like the excellent field. [8] It is to these that i teach dharma, teach-the-real beautiful in the beginning, beautiful in the middle and beautiful in the end both in spirit and letter, and to whom i make known the brahma-cariya, or-the-sublime-life completely fulfilled and utterly pristine. [9] For this reason, these people dwell with me for light, dwell with me for protection, dwell with me for strength, and dwell with me for refuge. [10] Again, my followers who are householders, both men and women. are like the middling field. [11] To these i also teach the dharma, or- teach-the-real beautiful in the beginning, beautiful in the middle and beautiful in the end, both in spirit and letter and to whom i make known the brahma-cariya, or-the-sublime-life completely fulfilled and utterly pristine. [12] For this reason, these people dwell with me for light, for protection, for strength, and for refuge. [13] Again, those recluses, brahmins and wanderers of other views apart from me are like the poor field with poor soil. [14] It is to these that i also teach the dharma, teach-the-real beautiful in the beginning, beautiful in the middle and beautiful in the end both in spirit and letter and to whom i make known the brahma-cariya, or-the-sublime-life completely fulfilled and utterly pristine. [15] The reason is, that if they were to understand even a single sentence, it would be for them a source of well being and good fortune, for a long time.

1.9

Uncompounded sutta. Udana. Pataligamiya chapter. Selected passage.

[1] It is called neither existing nor non existing, and this fact is dufficult to see. [2] But one who knows and sees in this way cuts through attachment-to-conditioned-things-as-self. [3] And one who sees in this way is no longer troubled by anything.

1.10

Satipatthana sutta. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, there is the eka-yana, or-the one-and-universal-way for the purification of beings, for the overcoming of sorrow and grief, for the subsiding of insecurity and misery, for the gaining of the balanced path and for the realization of nirvana, or-the-cool, that is to say, there is the fourfold foundation of awareness. And what are the four? Herein, a bhikkhu lives contemplating the body in the body with effort, clearly comprehending and aware, overcoming both the attempt to grasp at them and to push it away-as-self that is common in the world. [2] Again perceiving feelings in the feelings with effort, clearly comprehending and aware of them, overcoming both the the attempt to grasp at them and to push them away-as-self that is common in the world. [3] Again, perceiving desires-and-intentions in the desires-and-intentions with effort, clearly comprehending and aware of them, overcoming both the attempt to grasp at them and to push them away-as-self that is common in the world. [4] And again, perceiving thoughts-and-ideas in the thoughts-and-ideas with effort, clearly comprehending and aware of them, overcoming both the attempt grasp at them-as-self and to push them away that is common in the world.

1.11

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] How is the cleansing of awareness threefold? In this case one is not greedy, for one no longer wants the belongings of another with the thought: I want what they possess. [2] Again, one is neither hateful nor deceitful but wishes: May all living beings move about in peace, free from ill-will, free from distress and in happiness. [3] Again, one has a balanced view; is considerate in attitude and understands that there are such things as a gift, an offering, and a sacrifice together with the result and consequence of beneficial and harmful acts. [4] That this world exists; that the after world exists, that mother, father and beings arisen spontaneously exist. [5] That there are seekers and brahmins who go in balance, who live in balance and who have realized directly for themselves the-true-nature-of this world and the after world and proclaim it as such.

1.12

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, i do not dispute with the world but the world disputes with me. [2] A proclaimer of dharma, a-proclaimer-of-the-real does not dispute with anyone in the world. [3] For whatever is not accepted by the wise in the world, i also say: That is not so. [4] And whatever is accepted by the wise in the world, i also say: That is so. [5] And what, oh bhikkhus is not accepted by the wise in the world of which i also say: That is not so? [6] It is that the body is permanent, stable, eternal and not subject to decay. Of this i also say: That is not so? [7] Again, that feeling, memory-perception, intention, and unawakened-knowing are permanent, stable, eternal and not subject to decay are also not accepted in the world by the wise. And of this i also say: That is not so.

1.13

Itivuttaka. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, i am a brahman, one to ask a favour of, and always open handed. [2] I wear my last body-born-of-unseeing. [4] I am the incomparable physician and surgeon. [5] You are my true heirs, born of my teaching, born of the dharma, or-born-of-the-real and created by the dharma. [6] You are my spiritual heirs, and not my bodily heirs.

1.14

Dharmapada. Selected passage. Verses one to five.

[1] All that we are is the result of our thought. It is founded on our thought. It is made up of our thought. [2] If a person speaks or acts with harmful thoughts then sorrow follows like a cart wheel follows the foot of an ox. [3] All that we are is the result of our thought. It is founded on our thought. It is made up of our thought. [4] If a person speaks or acts with caring thoughts then happiness follows like a never departing shadow. [5] He abused me. He beat me. He overpowered me. He robbed me. Those who hold such thoughts never overcome ill will. [6] He abused me. He beat me. He overpowered me. He robbed me. Those who do not hold such thoughts, overcome ill will. [7] For ill will is not overcome through ill will but through good will. [8] This is the dhamma-san-antana, or-the-real-without-end.

1,15

Anguttara nikaya. Benefits sutta.

[1] Bhikkhus, there are eleven blessings to be seen from the heart liberation resulting from the development of metta, from-the-development-of-caring, by causing caring to grow, by causing it to increase, by causing caring to be the vehicle and basis, by maintaining it, by being intimate with it, and by being well established in it. And what are the eleven? One sleeps happily. [2] One awakens happily. [3] One has no harmful dreams. [4] One is dear to human beings. [5] One is dear to nonhuman beings. [6] One is protected by the devas. [7] One is not affected by fire, poison and sword. [8] One easily attains meditative-serenity. [9] One has a calm appearance. [10] One passes away without confusion. [11] And if one penetrates no further than this, one enters the brahma-loka, the-sublime-world. [12] These are the eleven blessings to be seen from the heart liberation resulting from the practice of merciful-caring-and-kindness.

1.16

Vinaya pitaka. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, i am freed from every snare, both that of devas and humans. [2] And you, bhikkhus, are also freed from every snare, both that of devas and humans. [3] Therefore, bhikkhus, go forth into the world for the benefit of the many, for the happiness of the many, out of caring for the world, for the wellbeing and happiness of devas and people. [4] Let not two of you go by the same way. [5] Thus may you teach the dharma, teach-the-real, beautiful in the beginning, beautiful in the middle and beautiful in the end and explain both in spirit and letter, the brahma-cariya, the-sublime-life completely fulfilled and utterly pure. [6] For there are beings with little dust in their eyes who by not hearing the dharma are wasting away, but upon hearing dharma will grow.

1.17

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, what is the nature of the noble ablution, the noble-washing which leads to the utter turning away, subsiding, and ending; to the peace, understanding and illumination; which leads to nibbana, or-leads-to-the-cool. [2] The ablution where beings who are subject to rebirth-in-unenlightened-states-of-existence are liberated and freed therefrom; where beings who are subject to decline are freed from decline; where beings who are subject to death are freed from death; where beings who are subject to dissatisfaction, remorse, sorrow, dejection and dispair are freed there from. [3] Bhikkhus, for one who has balanced view, mistaken view is washed away, and so too are washed away the various harmful and un-beneficial states that have arisen due to mistaken views, while the various beneficial and profitable states due to balanced-view come to fullness. [4] Again, for one who has balanced intention, speech, action, living, effort, mindful-awareness and meditative-serenity and for the one who has balanced knowing and liberation, then mistaken knowing and mistaken-notions of liberation are washed away, while the various beneficial and profitable states that are due to the balanced view come to fullness.

1.18

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] A bhikkhu’s attainment of meditative-serenity may be of such nature that in the midst of earth he is unaware of earth; in the midst of water he is unaware of water; in the midst of fire he is unaware of fire; in the midst of air he is unaware of air; in the the midst of the sphere of boundless space he is unaware of boundless space; in the the midst of the sphere of boundless consciousness he is unaware of boundless consciousness; in the midst of the sphere of no-thing he is unaware of no-thing; in the the midst of the sphere of neither perception nor non-perception, he is unaware of neither perception nor non-perception; in this world he is unaware of this world; in the after world he is unaware of the after world; in the midst of whatever is-dependently-arisen, seen, heard, sensed, known, attained, investigated and contemplated in awareness, he is also unaware. [2] And yet, even at this time there is still awareness i say.

1.19

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Ananda, it is through being a good friend to beings who are subject to arising in unawakened-states of existence that such beings are freed from arising in such states.

1.20

Udana. Selected passage.

[1] Such i heard. At one time. The exalted one was dwelling near savatthi, in the jeta grove of anathapindika’s park. [2] At that time, a number of wandering sectarians, recluses and brahmins enterd into savatthi to collect alms. [3] They were of different views, different convictions, different goals and different opinions arguing back and forth. [4] Now these recluses and brahmins held conflicting views such as: The world is eternal, this is the truth and all other views are fancy. [5] While others maintained that: The world is not eternal; this the truth and all other views are fancy. [6] Again others held: that the world is finite, or that the world is infinite, or that body and self are identical, or that body and self are different. [7] Again some held that the tathagata exists after death, or that the tathagata does not exist after death, or that the tathagata both exists and does not exist after death, or again, that the tathagata neither exists nor does not exist after death. [8] And so they lived quarreling, yelling and arguing with each other with abusive words piercing each other like arrows as they said: This is truth, or that is truth, or this or that is not the truth. [9] At that time, a number of bhikkhus, robing themselves and taking up their bowls went early into savatthi to receive alms, and upon their return, they took their meal and went to the exalted one, offered salutation and sat down to one side. [10] So seated, they described to the exalted one what they had seen and heard of those recluses and brahmins who held such one sided views. [11] Then the exalted spoke saying: Those who hold one sided views are blind and unseeing. [12] They know not the real from the unreal, nor fact from fancy. [13] And in this state of unseeing they quarrel and argue as you have described. [14] Oh bhikkhus, in the past their was a raja, a-king in this city-of-savatthi. [15] At that time, the raja called upon a certain individual saying: Come good man go forth and gather together all the blind men in savatthi. [16] Yes, your majesty, he replied, and in deference to the raja, gathered together all the blind men and took them to the raja saying: Your majesty, all the blind men of savatthi are now assembled. [17] Now my good man, may you now show these blind men an elephant. Yes your majesty, said the man, and he did as request saying: Oh sirs, this is an elephant. [18] To one man he presented the head of the elephant, to another the ear, to another a tusk, to another the trunk, or a foot, or the back, or the tail, or the tuft of the tail, saying to each one that this was the elephant. [19] Oh bhikkhus, when he had presented the elephant to each of the blind men, he went to the raja and said: Your majesty, the elephant has been presented to the blind men as requested.

[20] Then, oh bhikkhus, the raja went up to each of the blind men and asked: Have you examined the elephant? Yes, your majesty. Then what is your opinion? [21] Now those who had been presented with the head replied: Your majesty, the elephant is just like a pot. [22] And those who had been presented with the ear replied: The elephant is just like a winnowing basket. [23] And those who had been presented with the tusk replied: It is like a ploughshare. [24] And those who where presented with the trunk replied: It is like a plough. [25] Again some said the body was like a granary; or the foot like a pillar; or the back like a mortar; or its tail like a pestle, and the tuft of the tail like a broom. [26] Then they began arguing and shouting saying: It is like this, or it is like that, until they came to blows. [27] And when the raja saw this he was amazed. [28] Now in like manner are those who hold one sided views, for they are blind and unseeing and knowing not the factual, each maintains a one sided view.

1.21

Turning the dharma wheel sutta. Selected passage.

[1] Such I heard, at one time. [2] The exalted one was dwelling near banares, at isipatana, in the dear park. The exalted one then spoke to the five bhikkhus saying: Oh bhikkhus, there are two extremes that should not be followed by one gone forth. [3] Over indulgence, which is limited, troublesome, shallow, ignoble and harmful, and excessive self punishment, which is also painful, ignoble and harmful. [4] Oh monks, by avoiding these two extremes, the tathagata, the-such-come, has found the middle method-and-way which gives vision, which gives understanding, which leads to peace, higher knowing, full awakening and nirvana, the-cool-and-liberating.

1.22

Turning the dharma wheel sutta. Selected passage.

[1] Oh monks, and what is the middle way found by the tathagata, which gives vision, which gives understanding, which leads to peace, higher knowing, full awakening and nirvana? [2] It is the eightfold way-and-method of the noble ones, namely: balanced view, balanced intention, balanced speech, balanced conduct, balanced livelihood, balanced effort, balanced mindfulness and balanced concentration. [3] This, oh bhikkhus, is the middle way found by the tathagata which gives vision, which gives understanding, which leads to peace, higher knowing, full awakening and nirvana.

1.23

Turning the dharma wheel sutta. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, this is the noble fact concerning dukkha, dissatisfaction-and-insecurity: birth is insecure, aging is insecure, sickness is insecure, death is insecure, sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief and despair are insecure, getting what is not wanted is insecure, not getting what is wanted is insecure, in short the five khandhas, the-fivefold-complex-of-sensations-feelings-memories-desires-and-thoughts comprising a person, which are both the source and object of grasping-at-as-self, are dukkha, without-lasting-satisaction-and-insecure.

1.24

Turning the dharma wheel sutta. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, now this is the noble fact of the origin of dukkha, of-dissatisfaction-and-insecurity: [2] It is the mistaken grasping-at-self, which conditions the state of existence, together with mistaken grasping at that-which-is-without-lasting-satisfaction, that seeks satisfaction now here and now there. [3] That is to say, the mistaken grasping at sensation-as-self, the mistaken grasping at existence-as-self, and the mistaken grasping at non existence-as-self.

1.25

Turning the dharma wheel sutta. Selected passage.

[1] Now this, oh bhikkhus, is the noble fact concerning the overcoming of dukkha, or-dissatisfaction-and-insecurity: [2] It is the complete fading away and overcoming, the turning away, the giving up, the letting go, and the liberation from this grasping-at-dependently-arisen-things-as self. [3] This, bhikkhus, is the noble fact of the method-and-practice leading to the overcoming of dukkha. That is to say; the noble eightfold method.

1.26

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, here in the deer park the tathagata, or-the-such-come, the arahat, or-the-noble-one, and the balanced and fully awakened one has turned the unsurpassed dharma wheel.

1,27

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] What is balanced view? [2] There are two aspects to balanced view. [3] There is that associated with unawakened-knowing which is beneficial and results in higher states of existence. [4] And then there is the balanced view of the ariyas, the-noble-ones, which is free of unawakened-knowing, which is supermundane, and a factor of the path. [5] And what is the balanced view associated with unawakened-knowing? [6] The view that there is the gift, the one to whom it is offered and the offering-itself; [7] that there is beneficial and harmful karma or-action that has its result and fruit; [8] that there is this world and the further world; [9] that there is mother and father; [10] that there are apparitional beings, and [11] that there are noble and virtuous bhikkhus and brahmans who have realized direct knowledge for themselves and who thereby illuminate both this world and the further world. [12] This is the balanced view that is associated with unawakened-knowing. [13] What then is the balanced view of the ariyas-the noble-ones? [14] Any such understanding, or faculty of insight, or power of insight, or the investigation of phenomenal-realities-as-nonself that is a factor of enlightenment, or the balanced view that is a factor of enlightenment that is present in one whose awareness is ennobled and free of unawakened-knowing, who has realized the method and maintains it in practice. [15] This is the balanced view of the ariyas, the-noble-ones, that is free of unawakened-knowing, is supermundane, and is a factor of the path.

1.28

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] The instructed disciple of the ariyas, the-noble-ones, sees form-and-appearances and so on as: This is not mine; I am not this; This is not myself. [2] So that when form-and-appearances and so on change and become altered, there does not arise grief, sorrow, dissatisfaction-and-insecruity, lamentation and despair.

1.29

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] The instructed disciple of the ariyas, the noble-ones, does not regard appearing-colour-form as the self, nor the self as possessing appearing-colour-form, nor appearing-colour-form as being in the self, nor the self as being in appearing-colour-form. Nor does he regard feeling, perception, intention and thought in any of these ways. [2] He understands each of these khandhas, or-each-of these-complexes as it truly is, as ever-changing, insecure, nonself, constructed, and mortal. [3] He does not approach them, grasp at them nor regard them as: This is myself. [4] And this is conducive to his wellbeing and happiness for a long time.

1.30

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, i will teach you the burden and the bearer of the burden. [2] The panca-khandha, or-the-fivefold-complex, is the burden, while the pudgala, or-the-ego, is the bearer of the burden. [3] One who says that there is no self at all, is mistaken in their understanding.

1,31

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] If one does not see an unconditioned-self, or anything of an unconditioned-self in the panca-khandha, in-the-five-fold-complexes-of-grasping, then one is an arahat with the habitual tendencies overcome.

1.32

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] An uninstructed person does not think wisely if he thinks: In the past i was!; or: I was not!; or: What was i?; or: What was i like?; or: Having been such, how was i then? Or if he thinks: In the future will i exist?; or: Will i not exist?; or: How will i exist?; or: What will i be like?; or: Having been such and such, what will i become? Or if he is doubtful about himself at present and thinks: Am i?; or: Am i not?; or: What am i?; or: What am i like?; or: Where did i come from?; or: Where am i going and what will become of me? [2] To one who thinks in these ways without insight, one of six mistaken views may arise as if true and real, that is to say: There is myself!; or: There is not myself!; or: By self i am aware of self!; or: By self i am aware of no-self!; or: By no-self i am aware of my-self! [3] Or he may have the mistaken view such as: This self of mine that speaks and knows, that experiences now here and now there, the results of karma, or-of-actions-of-thought-word-and-deed that are pleasant or unpleasant, this self of mine is permanent, stable, unchanging and will remain forever! [4] This is what is called mistaken views, the holding of mistaken views, mere speculation and the shifting obstacle of mistaken views. [5] And bound by this obstcle, the uninformed person is not liberated from birth, aging and death, nor from grief, sorrow, lamentation, dissatisfaction, and despair.

1.33

Kacca-yana gotta sutta. Samyutta nikaya.

[1] Such i heard, at one time. The exalted one was dwelling in savatthi, at the retreat of anathapindika, within the jeta grove. [2] At that time the venerable kacca-yana-gotta approached him, offered salutation and sat down to one side. [3] So seated, he questioned the exalted one saying: Sir, people speak of balanced view. Now, to what extent is there balanced view? [4] Oh kacca-yana, the world generally tends towards these two extreme-views: either that of eternal-existence or that of utter-non-existence. [5] But for one who sees factually with balanced insight how the world arises, then the idea that the world is utterly-non-existent does not occur. [6] Again, kacca-yana, for one who sees factually with balanced insight, how the world passes away, then the idea that the world is eternally-existent does not occur. [7] Kacca-yana, for the most part, the world is bound by these approaches, graspings and tendencies. [8] But for one who does not follow these approaches and graspings, these characterizations, tendencies and attitudes of awareness, and who does not grasp or hold the view: This is my self. [9] But who thinks: Only that which is insecure and subject to arising, arises, and only that which is insecure and subject to passing-away, passes-away. [10] Such a person is thereby free from doubt and free from confusion. [11] In this case that person’s understanding is not dependent on externals. [12] In this way, kacca-yana, there is balance view. [13] Kacca-yana, that everything is eternally-existent, is one extreme. [14] Or, kacca-yana, that everything becomes utterly-non existent, is the other extreme view. [15] Kacca-yana, by avoiding both extremes, the tathagata teaches dharma, or-teaches-the-real by means of the middle. [16] That is to say, not-seeing, conditions mistaken-intentional-action. Mistaken-intention, conditions mistaken-awareness. Mistaken-awareness conditions thought and appearance. Mistaken-nature of thought and appearance conditions the six sense spheres. Mistaken-six sense spheres condition sensation. Mistaken-sensation conditions feeling. Mistaken-feeling conditions grasping. Mistaken-grasping, conditions clinging. Mistaken-clinging, conditions the states of unawakened-being. Mistaken-states of unawakened-being, condition-the-nature of birth. The mistaken-nature of birth, conditions-the-nature of old age, death, sorrow, lamentation, insecurity, dejection and despair. This is how the whole mass of dukkha, of-dissatisfaction-and-insecurity arises. [8] Now with the complete fading-away and overcoming of not-seeing, mistaken-intention is overcome. With the overcoming of mistaken-intention, mistaken-awareness is overcome. With the overcoming of mistaken-awareness, mistaken-thought and appearance is overcome. With the overcoming of mistaken-thought and appearance, the mistaken-six sense spheres are overcome. With the overcoming of the mistaken-six sense spheres, mistaken-sensation is overcome. With the overcoming of mistaken-sensation, mistaken-feeling is overcome. With the overcoming of mistaken-feeling, mistaken-grasping is overcome. With the overcoming of mistaken-grasping, mistaken-clinging is overcome. With the overcoming of mistaken-clinging, the mistaken-states of unawakened-existing are overcome. With the overcoming of the mistaken-states of unawakened-existence, the mistaken-nature of birth is overcome. With the overcoming of the mistaken-nature of birth; old age, death, sorrow, lamentation, insecurity, dejection and despair are overcome. And this is how the whole mass of dukkha, of-dissatisfaction-insecurity, is overcome.

1.34

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] The person who does not know of the ariyas, the-noble-ones, lives with awareness overwhelmed and enslaved by the view that the ego is the self; [2] by the uncertainty regarding the true nature of the world; [3] by mistaking rule and ritual as an end in itself; [4] by infatuation with sensation and ill-will, and [5] is unable to see any freedom from these when they arise. These are called the five gross-fetters and when not overcome, they remain habitually.

1.35

Digha nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] The five subtle fetters are: attachment to pure-appearances-as-the-self; [2] the attachment to the absence of all-appearance-as-the-self; [3] basic-ego-centric-conceit;

[4] basic-anxiety-and-fear, and [5] the basic-unseeing-and-unknowing.

1.36

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] There are those bhikkhus who by overcoming the first three fetters, have entered the stream, who are no longer subject to reappear in the worlds of dispair, who are established in ethical-conduct and who are destined to awakening. [2] Again, there are bhikkhus who by overcoming the three fetters and by weakening infatuation, ill-will and unawareness have become once-returners, who by returning only once to this world of unawakened-state, will accomplish the overcoming of dukkha, the-overcoming-of dissatisfaction-insecurity. [3] Again, there are bhikkhus who by completely overcoming these five gross fetters are destined to spontaneously appear in the further-world and will therein realize nirvana, never-returning from that world. [4] Again, there are bhikkhus who are arahants, who-are-worthy-and-noble-ones with their fetters overcome, who have lived the brahmacariya, or-the-sublime-life; completed the task; put down the burden; realize the gaol; overcome the fetters, and who are freed through direct knowing for themselves.

1.37

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] What is balanced will-and-intention? [2] It is the will to non-attachment-to-things-as-the-self; [3] the will to non-violence, [4] and the will to non-cruelty. [5] This is called a balanced will.

1.38

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Even if bandits with a two-handed saw, brutally severe limb from limb, if because of this one holds ill will in one’s heart towards them, then one is not a follower of my teaching.

1.39

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] What is balanced speech? [2] To refrain from lying, slander, abuse and gossip. [3] This is called balanced speech.

1.40

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] What is balanced action? [2] To refrain from causing harm to breathing things, from taking what is not given, and from excess. [3] This is called balanced conduct.

1.41

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] When a householder is possessed of five things, the househloder lives securely at home, and will arise in the deva-world as surely as if he had been lifted up and put there. [2] And what are these five things? [3] He undertakes the training in non-harming breathing beings; in not taking what is not given; in non-disloyalty; in not speaking untruth, and further in the non abuse of liquor, wine and fermented brews which can result in future regret.

1.42

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] What is balanced livelihood? [2] Herein, a noble follower gives up harmful means of livelihood and obtains their living through balanced means of livelihood.

1.43

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, there are five means of livelihood that ought not to be followed by a householder. [2] And what are the five? [3] They are trade in weapons; trade in living beings; trade in flesh; trade in fermented drinks, and trade in poison.

1.44

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Scheming-deception; forcing; hinting; belittling and profiteering are called wrong means of livelihood for bhikkhus.

1.45

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] What is balanced effort? Herein a bhikkhu calls forth desire for the non-arising of as yet non-arisen harmful and unbeneficial states, for which he puts forth effort, arouses energy, applies awareness and exertion. [2] He calls forth desire for the letting go of those harmful and unbeneficial states that have already arisen, for which he puts forth effort, arouses energy, applies awareness and exertion. [3] He calls forth desire for the arising of as yet non-arisen beneficial states, for which he puts forth effort, arouses energy, applies awareness and exertion. [4] He calls forth desire for the continuance, the non-decline, the strengthening, the maintaining, and the further development of beneficial states already arisen, for which he puts forth effort, arouses energy, applies awareness and exertion. [5] This is called balanced effort.

1.46

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] What is balanced mindful-awareness? [2] Herein a bhikkhu lives contemplating the body in the body, with effort, clearly comprehending it and mindful of it, overcoming the tendencies to both grasp at it-as-self, or to push it away that are common in the world. [3] Again perceiving feelings in the feelings, with effort, clearly comprehending them and mindful of them, overcoming the tendency to both grasp at them-as-the-self or to push them away that is common in the world. [4] Again perceiving desires-intentions in the desires-intentions with effort, clearly comprehending them and mindful of them, overcoming the tendency to both grasp at them-as-self or to push them away that is common in the world. [5] Again perceiving all ideas and things in all ideas and things with effort, clearly comprehending them and mindful of them, overcoming the tendency to both grasp at them-as-self or to push them away that is common in the world. [6] This is called balanced mindful-awareness.

1.47

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, i will teach you the arising and vanishing of the four foundations of mindfulness, that is to say: The body has nutriment for its arising and it vanishes with the absence of nutriment. [2] Feelings have sensation for their arising and they vanish with the absence of sensation. [3] Desires-and-intentions have awareness and appearances-to-awareness for their arising and they vanish with the absence of awareness and the appearances-to-awareness. [4] Again, ideas and thoughts have attentive-awareness for their arising, and they vanish with the absence of attentive-awareness.

1.48

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] All mistaken-phenomena have mistaken-grasping-at-self as their origin; [2] mistaken-attention gives them being; [3] mistaken-sensation is their arising; [4] mistaken-feeling is interaction with them; [5] concentration is the interface with them; [6] awareness is mastery over them; [7] insight-into-non-selfness is the transcendence of them, and [8] liberation is their very core.

1.49

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] What is balanced samadhi, or balanced-meditative-absorption? [2] Herein a bhikkhu secluded from sensations and secluded from harmful mental states enters and dwells in the first absorption which is associated with intial-thought; with sustained-thinking; with rapture, and with happiness arisen from seclusion-from-distraction. [3] And with the subsiding of initial-thought and sustained-thinking and by gaining inner calm and one-pointedness he enters and dwells in the second absorption that is without initial-thought and sustained-thinking but has rapture and happiness, arisen from meditative-absorption. [4] And with the subsiding of rapture while dwelling in onlooking-equanimity; mindful and fully aware, feeling peace both in and throughout his entire person, he enters and dwells in the third absorption of which the ariyas-the-noble-ones say: He has a pleasant abode, who dwells in equanimity and awareness. [5] And again, with the overcoming of pleasure and pain and with the subsiding of that former happiness and grief, he enters and dwells in the fourth absorption which has neither pleasure nor pain wherein clarity of awareness arises from upekkha, from-onlooking-unbiased-equanimity.

1.50

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] With the complete subsiding of perceptions of rupa, of- appearance-with-colour-and-form, and with the vanishing of perceptions of boundaries and with the non-perception of this and that, a bhikkhu enters and dwells in the perception of the sphere of boundless-spaciousness. [2] Again, with the complete subsiding of the perception of the sphere of boundless-space but still with the perception of boundless-perception, he enters and dwells in the perception of the sphere of boundless-perception. [3] Again, with the complete subsiding of the perception of the sphere of boundless-perception but with the perception of nothing at all, he enters and dwells in the perception of the sphere where there is nothing at all. [4] Again, with the complete subsiding of the perception of the sphere where there is nothing at all, he then enters and dwells in the sphere of neither perception nor non-perception.

1.51

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] The four absorption's of appearance-with-colour-form, are not called liberation in the training of the ariyas, the-noble ones. [2] In the noble training, they are called pleasant abodes here and now. [3] Again, the four formless absorptions-without-appearance-of-colour-and-form are not called liberation in the training of the noble ones. [4] Rather, in the noble training, they are called peaceful abodes.

1.52

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] With the complete subsiding of the sphere of neither-perception-nor-non-perception, a bhikkhu enters and dwells in the-overcoming-and-cessation-of-perception-and-feeling and his faults are ended by direct-knowing and vision. [2] In this case, a bhikkhu is said to have deprived mara, or-the-mortal-one of eyesight, to be invisible to mara, and furthermore, to have overcome all attachment to the world-as-the-self.

1.53

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] The bhikkhu who practices the eight jhanas, or the-eight-absorbtions, is said to have temporarily-blindfolded mara, the-mortal-one; to have temporarily deprived mara of eyesight, and to be invisible to mara.

1.54

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] One morning the venerable ananda dressed and taking his bowl and outer robe went out into savatthi for alms. [2] Then he saw janussoni, the brahman, driving out of savatthi in a chariot drawn by four white horses, fine white steeds, with white harnesses, with a white chariot, white upholstery, white sandals and even with a white fan, fanning him. [3] And when the people saw this, they exclaimed: Now that truly is a brahma vehicle! Truly that is like a brahma vehicle! [4] And upon returning, the venerable ananda told all this to the exalted one, and then asked: Can one point out a brahma vehicle in this dhamma and training? [5] The exalted one then said to ananda: Yes one can, for brahma vehicle is a name for the eightfold method, and so too is dhamma vehicle, and so too is supreme victory in battle. [6] For all aspects of the eightfold method culminate in the overcoming of attachment, ill-will, and unawareness of the impermanence-insecurity-and-nonselfness-of-all-things.

1.55

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] It is cetena, or choice-and-intention, that i call karma, or intentional-action-of-thought-word-and-deed. [2] It is through choice that a person performs karma, performs-action through body, speech and mind. [3] Again, there is karma, that will ripen as the hellish, brutal, ghostly, human, and deva worlds-of-unawakened-existence in one of three ways, either in the present, or the near future, or in some future existence.

1.56

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] What is nutriment? [2] There are four kinds of nutriment that sustain those who are already in unawakened-existence and assist those who are seeking renewed existence. [3] They are gross and subtle physical food; sensation; choice; and unseeing.

1.57

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh monks, greed is a condition for the arising of karma, for-the-arising-of-action-through-thought-word-and-deed; [2] ill-will is a condition for the arising of karma, and [3] unseeing-unawareness is a condition for the arising of karma.

1.58

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] When burning with greed; filled with ill-will and confused by unawareness, a person who is overwhelmed and controlled by these causes sorrow for themselves; causes sorrow for others, and causes sorrow for both. [2] And for this-reason experiences both grief and sorrow due their own karma, due-to-their-own-actions.

1.59

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Living beings are owners of their karma, or their-unawakened-actions-of-thought-word-and-deed; heirs of their karma, with karma as their ancestor, with karma as their relation, and with karma as their dwelling place and shelter. [2] It is karma, that differentiates living beings into higher and lower states of unawakened-existence.

1.60

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] What is past karma, past-unawakened-action-of-thought-word-and-deed? [2] It is unawakened-seeing, hearing, smelling, taste, touch and thinking that are past karma that has already been willfully performed and must be experienced in order to be known. [3] What is present karma? [4] It is whatever karma, whatever-action, that one does at present through deed, word and thought.

1.61

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] This unawakened-life belongs neither to oneself nor to another. [2] It is past karma, or-past-unawakened-actions-of-thought-word-and-deed that has already been performed and intended and must be experienced in order to be known.

1.62

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Karma, or-unawakened-action-in-thought-word-and-deed, based in greed, ill-will and unawareness ripens wherever-not-seeing-prevails, and wherever karma ripens there is the experience of this ripening either in the present, future, or in some later existence.

1.63

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] There are four in-concievables which cannot be directly known-conceptually and any attempt to directly-know them conceptually will lead to frustration and delirium. [2] What are the four? [3] They are the objective field of the buddhas, the-fully-awakened-ones. [4] The objective field of those who have attained the jhanas, or-the-meditative-absorptions. [5] The ripening of karma, or-the-unawakened-actions-of-thought-word-and-deed. [6] And the extent of the universe.

1.64

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Health is the greatest blessing. [2] Nirvana is the greatest peace. [3] And the eightfold method is the greatest method leading to the secure, to the immortal and deathless.

1.65

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] And what is the consequence of dukkha, or-dissatisfaction-and-insecurity? [2] When someone’s awareness is overwhelmed and preoccupied with dissatisfaction, one either sorrows, laments, beats the chest, weeps and is confused, or one begins to search for the other, for-the-further-and-the-beyond thinking: Who is there that knows but one or two words leading to the overcoming of dukkha, to-the-ovecoming-of-dissatisfaction-insecurity? [3] For i say, that the result of dukkha is either more perplexity, or the beginning of the search.

1.66

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] In the noble training, the term loka, or-the-world, refers to the world by which one perceives the world and conceives views about the world. [2] And what is there in the world by which one does this? [3] It is unawakened-seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching and thinking.

1.67

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] It is called the loka, or-the-world, because it wears away.

1.68

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] There is sila, balanced-action; there is samadhi-balanced-meditative-concentration; there is panna, balanced-penetrating-insight, and there is vimutti, liberation-and-freedom. [2] When based in beneficial-action, meditative-concentration brings higher fruit and blessing. [3] When based in meditative-concentration, penetrating-insight brings higher fruit and blessing. [4] When based in penetrating-insight, awareness becomes liberated from all faults, namely the fault of attachment to sensations-as-self, the fault of existence-conditioned-by-unseeing, the fault of mistaken-views, and the fault of not seeing.

1.69

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, inconceivable is the first beginning of the thirst for becoming, before which it was nonexistent and after which it came into being. [2] However, a main condition for the thirst for becoming is conceivable. [3] Again, bhikkhus, i say that this thirst for becoming has a sustaining condition and does not occur without it. [4] And what is that? [5] It is unawakened-seeing. [6] For both the unawakened-thirst for becoming, and unawakened-seeing are the primary causes that lead to both pleasant and unpleasant states of unawakened-existence.

1.70

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Suppose someone were to throw a yoke into the ocean with one opening in it so that the east wind blows it to the west, the west wind blows it to the east, the north wind blows it towards the south and the south wind blows it towards the north. [2] And suppose there was a blind turtle that arose to the surface once every hundred years. [3] Bhikkhus, what do you think, would that turtle eventually put his head through the single opening in the yoke? Yes sir, after a long period of time it might be possible. [4] However, bhikkhus, that blind turtle would sooner put his head through that single opening in the yoke, than the unseeing-being, once they have fallen into the distressful-hellish-states, would return to the human state. [5] The reason is, that there is no dhamma, no-understanding-of-the-real therein, no balanced-living, no doing of what is appropriate and no doing of what is good.[6] Oh bhikkhus, therein is the devouring of each other by each other and the feeding on the weak. [7] Again, bhikkhus, if after a long period of time the unseeing-being does return to the human state, they would be born into poor families or into a family of hunters or of bamboo-workers or a family of cart wrights or a family of garbage-pickers or in such families as are destitute without food and drink and where clothing to cover the body is difficult to obtain. [8] Furthermore, they will be ill-favoured, or unpleasant to look at, or stunted, or sickly, or blind or deformed or lame or paralyzed. [9] They would be unable to obtain food, drink, clothing, vehicles, garlands, scents, bedding, dwelling and light. [10] They would live unbalanced in deed, word and thought. [11] And because they live unbalanced in deed, word and thought, when their body breaks up at death, they will again arise in the distressful-states, in an unfortunate birth, in a downfall, in the hellish-state of niraya.

1.71

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, i have revealed to you that the dhamma, or-the-way-of-reality is like a raft for crossing over and not for grasping at-as-an-end-in-itself. [2] Bhikkhus, through understanding the parable of the raft you should know that you must go beyond even balanced views of dharma, how much more so mistaken views of dharma.

1.72

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh monks, i know of no other thing greater than mistaken views by which harmful things not yet arisen arise and by which harmful things already arisen grow and increase. [2] I know of no other thing greater than mistaken views by which beneficial things not yet arisen are hindered in their arising, and the beneficial things already arisen subside. [3] I know of no other thing greater than mistaken views by which human beings at the breaking up of the body, at death, pass away into the unpleasant, into a world of sorrow, into a hellish-state.

1.73

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] By criticizing that which should be criticized and praising that which should be praised, the exalted one is a vibhajja-vadin, a-discerning-speaker, and not one sided in his speech.

1.74

Samyutta nikaya. Selected assuage.

[1] Now if one holds the view that the life-principle is identical with the body, then the profound-life would be impossible. [2] Again, if one holds the view that the life-principle is entirely different from the body, then the profound-life would also be impossible. [3] The tathagata avoids both these extreme views and so reveals the majjhima-dhamma, or-the-middle-view-of-reality.

1.75

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh monks, i know of no other thing other than an attractive object through which attachment to sensation-as-the-self, may arise and once arisen continue to grow and increase. [2] For one who does not consider an attractive object with insight-as-nonself, in him attachment to sensation-as-the-self, will arise, and once arisen will continue to grow.

1.76

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, there are two luminous principles that protect the world: They are hiri, or-respect-for-self, and ottappa, or-respect-for-others. [2] If these two principles did not exist to protect the world, then one would not respect one’s mother, nor one’s mother’s sister, nor one’s brother’s wife, nor one’s teacher’s wife.

1.77

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] When unseeing has been overcome and seeing has arisen, one no longer grasps at material-form-as-the-self, nor at mistaken views, nor at rules and rituals as ends in themselves, nor at mistaken-notions-of-conditioned-things.

1.78

Digha nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, how does a bhikkhu dwell mindful of the body in the body? [2] Herein, a bhikkhu enters the forest, or sits at the base of a tree, or goes to some empty place and sits crossed legged, with body erect and with awareness brought forth and established in him. [3] Mindfully he inhales and mindfully he exhales. [4] If he inhales a deep breath he is aware of it. [4] If he exhales a deep breath he is aware of it. [5] If he either inhales a shallow breath or exhales a shallow breath, he is aware of it. [6] He practices with the thought: Aware of my whole body, i inhale. [7] He practices with the thought: Aware of my whole body, i exhale. [8] He practices with the thought: Relaxing my entire bodily state, i inhale. [9] He practices with the thought: Relaxing my entire bodily state, i exhale. [10] Just as a skilled turner, or a turners apprentice when pulling a cord to full length, is aware that he is doing so, or in pulling a cord to a short length, is aware that he is doing so, so too, is the bhikkhu with regard to the body, he continues to contemplate the body both internally and externally. [11] He continues contemplating the arising of bodily phenomena. [12] He continues contemplating the passing away of bodily phenomena. [13]

He continues contemplating both the arising and passing away of bodily phenomena. [14] Again, he is mindful of the presence of the body to the degree necessary for awareness and attentiveness. [15] And so he dwells independently, without grasping at anything in the world-as-self. [16] This is how a bhikkhu dwells mindful of the body in the body.

1.79

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, by protecting oneself, one protects others and by protecting others, one protects oneself. [2] And how, bhikkhus, does one protect others by protecting oneself? [3] Through the regular practice, development and increase of the foundations of mindful-awareness. [4] Thus, oh bhikkhus, one protects others by protecting oneself. [5] And how, bhikkhus, does one protect oneself by protecting others? [6] It is through patience, non-violence, caring, and compassion towards others that one protects oneself.

1.80

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh rahula, be like the earth and there remain, for by doing so, when unpleasant or pleasant sensations arise, they will not overwhelm your awareness. [2] For just as when people drop clean or dirty things, excrement, urine, spit, pus or blood on the earth, the earth is not ashamed, humiliated nor disgusted thereby. [3] Again, rahula, be like water, for when people wash with water, the water is not ashamed, humiliated nor disgusted thereby. [4] Again, rahula, be like fire, for whatever fire happens to burn, the fire is not ashamed, humiliated nor disgusted thereby. [5] Again, rahula, be like air and there remain, for in so doing, when unpleasant or pleasant sensations arise, they will not overwhelm your awareness. [6] For just as when air blows away clean or dirty things, excrement, urine, spit, pus or blood, the air is not ashamed, humiliated nor disgusted thereby. [7] Again, Rahula, be like space and there remain, for in so doing, when unpleasant or pleasant sensations arise, they will not overwhelm your awareness. [8] For space has no particular location of its own. [9] Practice metta, or-mercy-and-kindness in order to remove resentment. [10] Practice karuna, or-compassion-and-concern, in order to remove cruelty. [11] Practice piti or-empathy in order to remove apathy.

[12] Practice upekkha, or-unbiasedness in order to remove dislike. [13] Practice contemplating the corruptable-nature of the body, in order to remove obsession with it. [14] Practice the contemplation of impermanence in order to remove the conceit: I am. [15] And practice mindful-awareness of breathing, for when this is maintained and developed it brings much benefit and great blessing.

1.81

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] At one time the exalted one was dwelling in the sumbha territory, at the town of sedaka of the sumbha people. [2] There, the exalted one said to the bhikkhus: Oh bhikkhus, suppose a large group of people gathered together and exclaimed: A beauty queen! A beauty queen! [3] And that beauty queen was also very skilled in the performance of singing and dancing so that even a larger group of people would gather together exclaiming: A beauty queen is dancing and singing! [4] Then there arrives a man who desires life over death and well being over ill being. [5] The people then say to him: Look, here is a bowl of oil filled to the brim. You must now carry it around amongst the large gathering of people surrounding the beauty queen while a man holding an uplifted sword follows behind you, so that if you spill even a drop of oil he will chop your head off. [6] Now bhikkhus, what do you think? Would that man then lose his attention on the bowl of oil by allowing himself to be distracted by externals? Surely not, sir. [7] Now bhikkhus, it is by means of this parable that i wish to clarify the intended meaning: [8] The bowl filled to the brim with oil, signifies mindful-awareness of the body. [9] And for this reason, oh bhikkhus, you must train yourselves: Mindful-awareness of the body will be well developed and increased, and will be for us a vehicle and foundation. It will become developed, established and consummate in us. [5] Oh bhikkhus, this is how you must train yourselves.

1.82

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, what are the five advantages of a suitable dwelling place? [2] Such a dwelling place is neither too far nor to close and is suitable for coming and going. [3] During the day it is uncrowded and at night is free of noise and activity. [4] One is little bothered by flies, mosquitoes, wind, sun and creeping things. [5] While living there, it is easy for the bhikkhu to obtain clothing, alms-food, shelter and the appropriate medicines. [6] And there are elder bhikkhus living there who are learned and well versed in the teaching, who are masters of the dhamma and the summaries, to whom he approaches from time to time in order to ask questions and receive answers.

1.83

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, what is the development of the power of awareness? [2] Bhikkhus, herein, a bhikkhu develops the factors of enlightenment which tend toward solitude, non-attachment, overcoming and finally end in liberation, that is to say: mindful-awareness; investigation of the dharma; effort; joy; serenity; concentration, and choiceless-equanimity. [3] Oh bhikkhus, this is called the development of the power of awareness.

1.84

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] I do not teach that the realization of supermundane-knowing arises immediately, but that it arises through a gradual training, a gradual practice, and a gradual path. [2] The reason is, that one who has saddha, or-devotion, who comes near, listens to, and hears the dharma or-hears-the-real, who keeps these things in awareness and puts them into practice so that their awareness is gladdened and so that mindful-awareness and effort arise in them. [3] Then as one further strives with determination, one realizes through insight the profound reality, and perceives it in all its detail.

1.85

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] That which is compounded-and-dependently-arisen, has three characteristics: an arising is apparent; [2] a vanishing is apparent, and [3] a change in what is presently existing is apparent.

1.86

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Nirodha, or-the-overcoming-cessation-and-transcendence of unawakened-existence, is nirvana, or-the-cool-and-liberating.

1.87

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] It is called nirvana, or-the-cool, because that burning thirst, based-in-not-seeing is gone.

1.88

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] The brahma-cariya, or-the-sublime-life is lived for the plunge into nirvana, or-the-plunge-into-the-cool; for the going-beyond-and-crossing-over-to-the-other-shore, and for consummation in nirvana, or-the-consummation-in-the-cool.

1.89

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Before my awakening, when i was still an unawakened bodhisattva, i thought of the household life as dusty and confining, while the life of going-forth is wide open. [2] For it is not easy while living the household life to live the brahma-cariya, or-the-sublime-life that is utterly complete and pure like a polished shell. [3] Now suppose i shave my hair and beard, put on the yellow robe, and go forth from the household life to the houseless life?

1.90

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Before my awakening, when i was still a unawakened bodhisattva, being myself subject to birth, aging, illness, death, sorrow and illusion, i used to seek that which is also subject to these things. [2] Then i thought: Why is it, that being myself subject to birth, aging, illness, death, sorrow and illusion, do i seek that which is also subject to these things? [3] Now suppose, being myself subject to these things and seeing the danger in them, i seek the unborn, the uncompounded, the un-aging, the immortal, the sorrowless, the non illusory and the overcoming of bondage that is nirvana, or-the-cool.

1.91

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Being myself subject to birth, aging, illness, death, sorrow and illusion, and seeing the danger in what is subject to these things, i sought the non-arising, the un-aging, the uncompounded, the immortal, the sorrowless, and the non illusory, the supreme overcoming of bondage that is nirvana, or-the-cool. [2] And then i realized it, so that such knowledge and vision was in me. [3] My liberation is unassailable. [4] This my last birth-as-a-unawakened-being. [5] There is no longer a renewal of unawakened-existence.

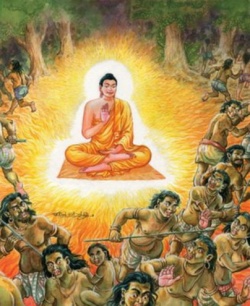

1.92

Mahavagga of the vinaya. Selected passage.

[1] Just as in a pond of blue, red or white lotuses that arise and grow in the water, there are some lotuses that live immersed in water without ever coming up out of it and other lotuses that arise and grow in the water only to rest on the surface of the water, and again there are still other lotuses that arise and grow in the water and rise out of the water so as to stand clear and un-effected by it. [2] So too, did gotama-the-buddha-the, see beings both with little dust in their eyes and with much dust in their eyes; with developed capacities and undeveloped capacities; with good qualities and harmful qualities; those easy to teach and difficult to teach and some who dwelt seeing both fear and blame in the other world. And having seen all this, the-buddha replied: [3] Open are the doors of the deathless. Let those who hear, place their trust therein. [4] For if i was considering not speaking of the dharma that i know, it was because i perceived much vexation in such speaking. [5] Then brahma-sahampati-deva thought: I have made it possible for the dharma, for-the-real, to be taught by the exalted one. [6] Then after he had offered homage-to-the-buddha, and while keeping him on his right side, he immediately vanished.

1.93

Mahavagga of the vinaya. Selected passage.

[1] Then just as a strong man quickly stretches forth and draws back his arm, brahma-sahampati-deva vanished from the brahma world and appeared before the exalted one. [2] Then placing his outer robe over one shoulder and his right knee on the ground, he placed the palms of his hands together and raised them towards the exalted one saying: Sir, may the bhagavan, may-the-exalted-one, proclaim the dharma, proclaim-the-real, may the sugata, or-the-well-going-one, proclaim the dharma. [3] For there are beings with little dust in their eyes, who through not hearing the dharma, are wasting away. [4] But there are some who-hearing-the-dharma may gain full knowledge therein. [5] And when brahma-sahampati-deva had said this, he further said: In magadha, up until now there has only appeared a clouded dharma taught by the those lacking insight. But now, open are the doors to the deathless, so that all who hear may enter the dharma, enter-the-real revealed by the faultless one.

1.94

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] First there is knowledge of the stability of the dharma, the-stability-of-the-real. [2] And later there is knowing of nirvana, knowing-the-cool.

1.95

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh malunkya-putta, what is it that i have not revealed? [2] I have not revealed whether the world is eternal or not eternal; [3] whether the world is finite or infinite; [4] whether life and the body are identical or whether life is one thing and the body another; [5] whether the tathagata does or does not exist after death; [6] whether the tathagata both exist and does not exist after death; [7] or whether the tathagata neither exists nor does not exist after death. [8] And malunkya-putta, why have i not revealed these things? [9] Malunkya-putta, it is because these things are not useful, they do not concern the ground of liberation, they are not conducive to turning away, to non-grasping, to overcoming, to serenity, to penetrating-insight, to awakening and to nirvana. [10] It is for this reason, that i have not revealed these things. [11] And malunkya-putta, what is it that has been revealed by me? [12] It is dukkha, or-dissatisfaction-and-insecurity that has been revealed by me. [13] It is the origin of dissatisfaction-and-insecurity that has been revealed by me. [14] It is the overcoming of insecurity that has been revealed by me.[15] And it is the method leading to the overcoming of dissatisfaction-and-insecurity that has been revealed by me.

1,96

Garavo Sutta. Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] I see nowhere in the world of devas, maras, brahmas, monks or ministers, nor among creatures human or divine, one who is more accomplished in these aspects other than my self under whom i could live with respect and reverence-as-my-teacher. [2] Therefore i will live under the dharma, under-the-real, respecting and revering the dharma-as-my-teacher, the very root of my highest and full awakening.

1.97

Garavo Sutta. Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] At that moment, brahma-sahampati-deva became aware of the exalted one’s thought and just as a strong man quickly stretches forth and draws back his arm, vanished from the brahma world and appeared before the exalted one. [2] Then brahma sahampati placed his outer robe over one shoulder and placing the palms of his hands together, raised his hands towards the exalted one and said: So it is, oh exalted one, oh well living one, that those exalted ones in the past who were arahats, balanced and fully awakened, also lived under the dharma, respecting and revering only the dharma. [3] Again those exalted ones, in the future who will be arahats, balanced and fully awakened, will also live under the dharma, respecting and revering only the dharma, the-real. [4] Therefore, oh sir, may the exalted one who is at present the arahat, balanced and fully awakened, also live under the dharma, respecting and revering only the dharma. [5] Having said this, brahma sahampati again said: [6] Those who were fully awakened ones in the past; who will be awakened ones in the future, and the fully awakened ones in the present, who slay the sorrows of the many, all live past, present and future holding in reverence the saddharma, or-the-supremely-real, as their guru, as-their-teacher. [7] Therefore, whoever wishes for wellbeing, and aspires for the greater self, should also live revering the saddharma, revering-the-supreme-reality as their guru, as-their-teacher, remembering the buddha word.

1.98

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh exalted one, in what sense is the world said to be empty? [2] Because it is empty of a permanent-self and what belongs to a permanent-self, therefore it is said that the world is empty. [3] And what is it that is empty of a permanent-self and what belongs to a permanent-self? [4] The eye, appearing-forms, visual knowing, and visual sensation are empty of a permanent-self and what belongs to a-permanent-self. [5] And so too, the ear, nose, tongue, body and awareness, sounds, smells, tastes, touch, thought and so on are empty of a permanent-self and what belongs to a permanent-self. [6] And any feeling that arises, conditioned by visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, tactile and cognitive sensation be it pleasant or unpleasant or neither pleasant nor unpleasant is also empty of a permanent-self and what belongs to a permanent-self. [7] This is the reason why the world is said to be empty, because it is empty of a permanent-self and what belongs to a permanent-self.

1.99

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] And what is the emptiness liberation of awareness? [2] As to this, a bhikkhu who has gone to the forest, to the root of a tree, or to an empty place contemplates thus: This is empty of a permanent-self and all that belongs to a permanent-self. [3] This is what is called the emptiness liberation of awareness.

1.100

Suttanipata. Selected passage.

[1] Regard the world as empty of separate-reality. [2] And ever mindful of this, up-root the mistaken view of a permanent-self-where-there-is-non. [3] And thus, mogha-rajah, will you go beyond mortality. [4] And knowing the world to be such, the king of death will not see you.

1.101

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Those ascetics and brahmans who rely in the impermanent, insecure and transient nature of appearing-forms, feelings, perceptions, intentions and thoughts as-a-permanent-self, mistakenly-think: Superior am i.; or they mistakenly think: Inferior am i.; or they mistakenly think: Equal am i. [2] And they imagine all this through not knowing reality as it truly is.

1.102

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] The conceit of feeling superior, the conceit of feeling inferior and the conceit of feeling equal, these three conceits need to be overcome. [2] For by overcoming these three conceits and through the complete penetration into the nature of conceit, a bhikkhu is said to have overcome dukkha, dissastifaction-and-insecurity.

1.103

Digha nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Sound, is not something that already exists in a conch shell and somehow comes out of it from time to time, but due the the conch shell and the person who blows into it, the sound then arises. [2] So too, due to the presence of life, energy, and thinking, this body may carry out the acts of going, standing, sitting and reclining. [3] And the five senses together with the knowing-sense, may carry out their functions.

1.104

Digha nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Even though a wooden puppet is empty of its own-separate-nature, without its own-separate life, and without its own-seperate-activity, through the pulling of stings it can be made to move around, stand and appear to be full of its own-life and full of its own-separate-activity. [2] So too, awareness and body are empty of their own-separate-reality, without their own-seperate-life and without their own-seperate-activity, but through the interaction-of-causes-and-conditions this mind-body system can be made to move around, stand, and appear to be full of its own-seperate-life and of its own-seperate-activity.

1.105

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] When all the constituent parts are present, the name of a cart is used. [2] So too, when the five complexes, of unawakened-sensation-feeling-memory-desire-and-awareness, are present, we speak of an unawakened-being.

1.106

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Short indeed is human life, finite and fleeting, full of insecurity and struggle; like a dew drop that vanishes with the rising of the sun; like a water bubble; like a line drawn on the surface of water; like a torrent sweeping everything along and never resting, and like cattle bound for slaughter who in every moment stare death in the face.

1.107

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhu, whatever there is of feeling, memory-perception and volition, these phenomena are interdependent and are not separate from each other. [2] It is not possible to divide one from the other and show them to be separately-existing. [3] For whatever one feels, one also perceives, and whatever one perceives, one also knows.

1.108

Anguttara nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] As soon as the day ends, or as soon as the night vanishes and the day begins, a bhikkhu considers thus: It is a fact that there are many possibilities for me to die. [2] I may be bitten by a snake, or stung by a scorpion or centipede and so may lose my life and this would be an obstacle for me. [3] Or i may stumble and fall to the ground, or i may eat food that does not agree with my state of health. [4] Or phlegm, bile and piercing gas cramps may distress me. [5] Or humans, or spirits may attack me and thus cause me to lose my life and again this would be an obstacle for me. [6] For this reason, a bhikkhu should consider the following: Are there still in me, as yet un-overcome harmful and un-beneficial states, that if i should die today or tonight may lead me into further states of ill-being? [6] Now if he understands that this is still the case, then he should put forth his utmost resolve, energy, effort, aspiration, determination, attention and clarity of mindfulness in order to overcome these harmful and un-beneficial things.

1.109

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Whatever there is of appearing-colour-form; feeling; memory-perception; desire, and awareness, be it past, present or future, internal or external, gross or subtle, sublime or ordinary, far or near, [2] One should understand according to reality and penetrating-insight: This is not mine. This is not-i. This is non-self.

1.110

Itivuttaka. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, this brahma-cariya, this-sublime-life is not lived for the sake of deception, nor for the sake of fooling people, nor for the sake of gain, honour, reputation and profit, nor with the thought: May people know me as such and such. [2] Bhikkhus, this brahma-cariya, this-sublime-life is lived for the sake of self training and liberation.

1.111

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] One who kills, or is cruel will arise in the hellish state, or if reborn in the human state, will be short lived. [2] One who torments others will be afflicted with disease. [3] One who is hateful will be of unattractive appearance. [4] The envious one will be without influence. [5] The stingy will be poor. [6] The obstinate will be of unfortunate descent. [7] The indolent will be without knowledge. [8] However, if the reverse is true, one will arise in the deva state or if reborn in the human state, will be long-lived; possess a pleasant appearance; be influential; of fortunate descent, and knowledgeable.

1.112

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] A synonym for the arahat, the-noble-and-freed-one is a brahman, a-sublime-one, who has crossed over and gone beyond to-the-other-shore, who stands on dry land.

1.113

Tathagata sutta. Itivuttaka. Selected passage.

[1] Oh bhikkhus, in the entire world with its hosts of devas, maras, brahmas, its hosts of recluses and brahmins, of devas and people, whatever there is, be it seen, heard, sensed, perceived, realized, searched into and pondered over, all this is fully known by the tathagata. [2] For this reason he is called the tathagata, the-such-come-who-is-in-the-world-but-not-fooled-by-the-world. [3] Whatever the tathagata utters, speaks and proclaims between the day of his awakening and the day of his passing, all that is just so and not otherwise. [4] For this reason he is called the tathagata. [5] Oh bhikkhus, as the tathagata speaks so he does; as he does so he speaks. [6] For this reason he is called the tathagata. [7] Oh bhikkhus, in the entire world with its devas, maras and brahmas, together with its host of recluses and brahmins, devas and people, the tathagata is the jina, the-unconquered, the all seeing and the all accomplished. [8] For this reason he is called the tathagata.

1.114

Majjhima nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] Ananda, whatever should be done for shravakas, for-those-who-listen, by a caring teacher who seeks their wellbeing and is compassionate, that i have done for you. [2] Here are the roots of trees. [3] Here are empty places. [4] Be not neglectful, lest you regret it later. [4] This is our instruction to you. [5] Thus spoke the exalted one. [6] Delighted, the venerable ananda rejoiced in what the exalted one had said.

1.115

Itivuttaka. Selected passage.

[1] I see no other hindrance, such as this one hindrance of avijja, of-unseeing-unawareness-and-ignorance obstructed by which people go around in circles for a long time.

1.116

Samyutta nikaya. Selected passage.

[1] That which we will, that which we intend, and that by which we are preoccupied, all that is the objective support of avijja, the objective support-of-unseeing. [2] If there is an object, there is a foothold for unseeing-and-unawareness. [3] Growing on this foothold, there is rebirth and the renewal of unawakened-existence in the future.

1.117

Digha nikaya. Selected passage.